Features

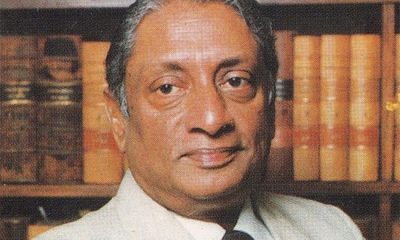

REFLECTIONS ON THE LIFE AND TIMES OF LAKSHMAN KADIRGAMAR

by Tissa Jayatillake

From the time I was old enough to cultivate an interest in politics, I have familiarized myself with the life and times of those political personalities I took a liking to. The late Dudley Senanayake (who incidentally died in 1973 a day after Lakshman Kadirgamar’s 41st birthday) was the first I took to and I consider it my loss that I did not have the opportunity to get to know him personally.

Of the several politicians that I have subsequently taken note of, there were two I got particularly close to and they were both, coincidentally enough, Oxonians who happened also to be presidents of the Oxford Union in their time. I refer to Lalith Athulathmudali and Lakshman Kadirgarmar. Athulathmudali did not attend a local university prior to going up to Oxford, as did Kadirgamar. The former’s cake, (to borrow a metaphor from Kadirgamar himself) was not baked at home, unlike that of the latter for whom Oxford was only the icing on his superlative, home-produced, academic confection.

Although Lakshman Kadirgamar and I belonged to two different generations, we shared certain commonalities. Though not of Kandy, we both had our early education in that city (he at Trinity, I at Kingswood) and we were both products of the University of Ceylon, Peradeniya. If memory serves, he was a resident of Arunachalam Hall, which was also where I spent my undergraduate years. He was a ‘citizen of the world’, a Sri Lankan and a Tamil. Likewise I, too, prefer to transcend narrow boundaries and take pride in being in that order, a human resident of this planet, a Sri Lankan, and then a Sinhalese.

I liked Kadirgamar’s academic bent of mind. If he and I were given to clichés, I would have called him ‘a voracious reader’. I should, instead, describe him as a man of books. And many were the times when we compared notes on literary texts we both had read and enjoyed. Not infrequently he telephoned me to double check on a quotation from a Shakespearean play that he wished to include in a lecture or a speech he was writing up. He publicly denounced bribery and corruption in public office, a particular aversion of mine, which is not a safe or fashionable public stance for a politician to take and I admired him for his courageous stand.

Furthermore he was unpretentious, charming, mellow-toned and possessed of a fine if often ironic sense of humour. And there was something else he was proud to be– an outstanding sportsman. The last attribute meant, by definition, that he was by instinct and training, fair-minded. Could one possibly ask for more? My one regret is that I did not get to know Lakshman Kadirgamar as intimately earlier than I actually did. I console myself with the thought that quality ever trumps quantity when it comes to most good things of life. As Ranil Wickremesinghe noted in the course of his tribute to Lakshman Kadirgamar in Parliament, a meal with the late minister offered food for the body as well as the mind. On most occasions a mere chat over a drink with him provided such nourishment for the soul.

Apart from our regular meetings to talk of issues of the day, there were two key projects dear to his heart that brought us together and helped cement our friendship. Given the rich heritage we Sri Lankans are heirs to, Lakshman Kadirgamar was of the view that we should give to the world, as he so aptly put it, ‘something more than just tea, tourism and terrorism’. He thus had a long-term plan to enable Sri Lanka to continue to contribute to the world of culture and the arts as also to the further refinement of international relations and diplomacy. It was his desire to have a book published on a Sri Lankan artist that would be ‘an ideal brand label for Sri Lanka, an image which may be projected all over the world as the face of Sri Lanka in all of its many forms’.

The result of his endeavours in this regard is the monumental and exquisite The World of Stanley Kirinde (2005) authored by Sinharajah Tammita-Delgoda. Having initiated the book project, he next set his sights on the production of an academic journal for the study of politics and diplomacy via the Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies (BCIS) of which he was now chairman. He invited me to serve as editor and together we put in many hours to get International Relations in a Globalizing World (IRGW) off the ground. Lakshman Kadirgamar’s last public act on the evening of that fateful twelfth of August, 2005, was to preside over the ceremony to mark the release of the inaugural issue of IRGW. It was Kadirgamar’s expectation, through the regular publication of IRGW, to raise the level of Sri Lanka’s contribution to diplomacy. All these best-laid plans and goals were shattered on that dreadful August night in 2005. Unfortunately Lakshman Kadirgamar did not live to see (though he saw the finished product and admiringly flipped through its pages) the release of The World of Stanley Kirinde scheduled for 18 August, 2005.

In this tenth year after his death, it is as good a time as any, to assess dispassionately the late foreign minister’s contribution to Sri Lanka and the world, and to imagine the kind of role he might have played had he lived beyond his 73rd year. I consider Lakshman Kadirgamar to be one of the finest twentieth century Sri Lankans and far and away the best foreign minister Sri Lanka has had to- date. He was widely read and intelligent and, at the same time, hard-working and disciplined. He had the courage of his convictions and the inner strength to hold fast to his ideals from his entry into the fickle world of politics in 1994 until his tragic end in 2005.

I tend to view Lakshman Kadirgamar’s performance on the domestic political front less enthusiastically than that of his on the international stage. It is entirely possible that my lukewarm view has less to do with any inadequacy of Kadirgamar’s and more to do with my aversion to realpolitik, especially to its Sri Lankan variety. As I have asserted in an earlier tribute to him (2005), Lakshman Kadirgamar was the quintessential Sri Lankan. Almost a year before his death, in September 2004, he made a profound statement on Japanese National Television (NHK) that encapsulated his credo:

I am first and foremost a citizen of Sri Lanka. I do not carry labels of race or religion or any other label. I would say quite simply that I have grown up with the philosophy that I am a citizen of the world. I do not subscribe to any particular philosophy; I have no fanaticism; I have no communalism. I believe there should be a united Sri Lanka. I believe that all our peoples can live together, they did live together. I think they must in the future learn to live together after this trauma is over. We have four major religions in the country: Buddhism, Islam, Hinduism and Christianity. All these religions exist very peacefully. They get on very well. I see no reason why the major races in the country, the Tamils and the Sinhalese, cannot again build a relationship of confidence and trust. That is my belief.

It is this fervent belief in the essential goodness of his country and fellow citizens that form the cornerstone of his diplomatic labours. It was also the driving force behind his brilliant and spellbinding performance as our foreign minister. I relished in particular the manner in which he finessed the challenge of LTTE terrorism. To say it was primarily Lakshman Kadirgamar’s powers of persuasion and skillful handling of domestic issues and their international ramifications that redeemed Sri Lanka’s sullied image is surely no exaggeration. Dedicated, experienced and effective Sri Lankan Foreign Service personnel played their part in this restoration process, but the helmsman was clearly Lakshman Kadirgamar.

In their measured tributes to a book published in honour of Lakshman Kadirgamar (Roberts: 2012), three seasoned American diplomats I know intimately, Karl (Rick) Inderfurth, Peter Burleigh and Shaun Donnelly who interacted closely with Kadirgamar have testified to the latter’s major successes on the international stage, during his lifetime and even posthumously. Chris Patten, the British politician, reinforces this fact when he notes in the same publication that:

Lakshman Kadirgamar spent much of his diplomatic energy and his formidable eloquence in attempting to persuade foreign governments to proscribe the LTTE in their own countries and stop the raising of funds for terrorism in Sri Lanka. He scorned the ‘Nelsonian’ attitude to terrorism of some countries. He was particularly active in supporting the drafting of the 1997 UN Convention for the Suppression of Terrorist Bombings. The respect he enjoyed internationally meant that his assassination nudged some foreign governments into taking a tougher line in prohibiting active support for the LTTE in their own countries.

Peter Burleigh in a recent personal communication reiterated this foremost aspect of Kadirgamar’s achievement when he noted:

I personally believe that his efforts to get important governments like Australia, the UK and the US to ban money transfers to the LTTE was a key contribution to the long-term effort to defeat the group. And his personal efforts, and effectiveness, in that regard were essential to that success.

Although I recognize that politics may well be the art of the possible, my limited experience of it as a practitioner and deeper awareness of it as student, make me conclude that politics is a murky and dismal business. I have often wondered why men of the sensitivity of Neelan Thiruchelvam and Lakshman Kadirgamar ever took to politics. In a statement over national television in 1994, Lakshman Kadirgamar spelt out his reasons for doing so. I quote below the operative paragraph of that statement:

I have had a privileged life by birth, by education, by access to opportunities, and I have always felt that a time must come when you must give something back to the society in which you have grown up and from which you have taken so much. So-called educated people must not shirk responsibilities in public life. I have reached that stage in life when, without being heroic about it, I feel I should participate more fully in public life.

Whilst not taking anything away from his invaluable and splendid contribution as foreign minister, I remain convinced that he could have given more back to the society from which, by his own admission, he had taken so much by opting for a different if less glamorous public role than that of a high visibility politician. As with similarly gifted men as S.W.R.D Bandaranaike, N.M Perera, Pieter Keuneman, Felix Dias Bandaranaike and Lalith Athulathmudali before him, I am left with the nagging feeling that his stint in politics somehow diminished Lakshman Kadirgamar in the end. Such diminution as occurred may well have been due to the corrosive nature of politics and not due to any inherent flaw in Kadirgamar’s character.

Perhaps he permitted his colleagues and his party to exploit his standing in society and his professional stature when he decided ‘without being heroic about it. . . [to] participate fully in public life’. Be this as it may, I remain disappointed by the narrow political role he played in the difficult and often acrimonious days of Sri Lanka’s French-style co-habitation government. This was the period between December 2001 and April 2004, when Kadirgamar’s party leader, Chandrika Kumaratunga, despite her party being out of power, was yet the constitutional head of government whilst Ranil Wickremesinghe as prime minister was in effective control of Parliament. Kadirgamar now was assigned the role of advisor to the president on international affairs, with Tyronne Fernando occupying the portfolio of foreign affairs.

On becoming prime minister in February 2002, Ranil Wickremesinghe entered into a Ceasefire Agreement (CFA) with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The CFA was brokered by the Norwegians, who were at the time involved in Sri Lanka’s peace process, and Wickremesinghe presented his cabinet and his president with a fait accompli. Although initially Kadirgamar’s statement in Parliament in 2002 in response to that of the prime minister reflected a refreshing degree of constructive cooperation, a little over a year later in a speech in Parliament on 8 May, 2003, doubtless on the authority of President Kumaratunga and the Parliamentary Group of the People’s Alliance, Kadirgamar attacked the CFA arguing that it was ‘a structurally flawed document’. Clearly Kadirgamar was here being sucked into petty politics as borne out by a subsequent observation of General Satish Nambiar, the well-known Indian strategic expert engaged by the government of Sri Lanka at that time. In a communication in January 2010 dealing with that fraught situation of 2003, Nambiar refers to a one-on-one lengthy meeting he had with Kadirgamar during his last visit to Sri Lanka in 2003. In the course of that meeting Nambiar had told Kadirgamar that he was hurt by the suggestions made by some of Kadirgamar’s party members that he [Nambiar] was manipulating his report. Nambiar comments:

[Kadirgamar’s]disarming response was typical of him: that I should allow for the politics of the situation where the parties will use any means to put the ruling dispensation on the defensive. [Roberts: p. 204]

When one reads Kadirgamar’s 8 May, 2003 speech in hindsight, one clearly recognizes that his arguments against the CFA are not without merit. But the key point that needs emphasis here is that by being a willing party to political manipulation of something as highly sensitive as the CFA, Kadirgamar had begun to slip somewhat from the lofty pedestal of statesmanship he had been on hitherto. In the process, Kadirgamar and his political companions failed to give any credit whatsoever or even the benefit of the doubt to Wickremesinghe.

We now know though that through the CFA the LTTE were led into a corner and to peace negotiations, with some even referring to it as ‘a peace trap’. Wickremesinghe’s CFA, for all of its ‘structural flaws’, was as much a ploy as was the Kumaratunga government’s 1998 decision to use the Norwegians as ‘facilitators’ in the unofficial conversations between the then government and the LTTE. And, yet, Kumaratunga and her paarty were now opposing, seemingly for the sake of opposition, the Norwegians (their ‘facilitators’) and Wickremesinghe, for the signing of the CFA with Kadirgamar lending his forensic debating skills for the cause in Parliament. A similar but less nationally harmful political misjudgement was Kadirgamar’s decision, despite sincere and pragmatic advice against the move from close associates, to contest the incumbent Secretary- General of the Commonwealth in 2003. He was roundly defeated by 40 to 11.

On balance, Kadirgamar’s overall achievement as politician and foreign minister, despite blemishes referred to above, is marvellous. Unlike the average gifted person who tends to rest on his laurels, Kadirgamar was exceedingly hard-working from beginning to end. Like a good lawyer, he always studied his brief well and, like a good sportsman, he was ever thorough in his preparation. It is this careful preparation in combination with his ability and flair that made Kadirgamar who he was. He was consistent and relentless in his opposition to political violence which he saw as a threat ‘to the stability within and between states throughout the world’.

Well before the cataclysmic ‘9/11’, he warned western governments of the dangers of terrorism and called for joint action to deal with the scourge. Among his several notable speeches on the problems of terrorism, perhaps the most influential was that he made at Chatham House, London, on 15 April, 1998 at a meeting held under the auspices of the Royal Institute of International Affairs and the International Foundation of Sri Lankans. ‘[A] terrorist act’,Kadirgamar asserted at Chatham House, ‘is seen as an attack on society as a whole, on democratic institutions, on the democratic way of life. A terrorist attack is an act of war against society’.

In similar vein was his lecture delivered on 13 September, 2010 at The Potomac Institute of Policy Studies in Washington D.C., approximately a year before ‘9/11’. Kadirgamar was thus resolute in his principled opposition to the use of violence as a means of seeking political gain, both at home and abroad. At the same time, he recognized our need to address the underlying causes that lead communities to acts of violence. Hence much as he decried the political violence of the LTTE, he did recognize the need for social and political justice to those marginalized citizens in our midst. In this context, the following remarks he made during an interview he gave to Business Today (Colombo, March 1997, p.20) are most salutary:

[T]he ultimate, permanent, durable solution to this problem will not come from force of arms alone. It will not come from conquest or our vanquishing the LTTE. It has to come by acceptance of the people in their entirety, by the Sinhala and the Tamil people. That is a political settlement. And, a political settlement that is perceived by the communities, by the majority and the minorities, to be fair and just. It must be a settlement that is enshrined in law, and it must be enshrined in the hearts of the people.

Thus Kadirgamar’s opposition to violence was both principled and pragmatic. However, he did not allow his justifiable antipathy to violence to ensnare Sri Lanka’s collective future. Lakshman Kadirgamar was no narrow nationalist. In pursuing a solution to the crisis of nation-building in Sri Lanka, he did not take a partisan stance. He was Sri Lankan to the core.

A tragedy in Lakshman Kadirgamar’s life and career is that neither the zealots among the Sinhalese who mourned his untimely death and cheered him on in life nor their counterparts within the Tamil community who rejoiced in his death and vilified him in life understood or yet understand the man. The Sinhala zealots mistook his opposition to the separatist extremism of the LTTE as a sign of his ‘pro-Sinhalaness’. The moral inadequacy of the zealots amongst the Tamils made it impossible for them to understand Kadirgamar’s heartfelt aversion to ethnic labels. It also led them to their erroneous conclusion that Kadirgamar’s championing of an overarching Sri Lankan identity was an act of political expediency at best and a manifestation of ‘anti-Tamilness’ at worst. The continuing tragedy of Sri Lanka is that there are too many amongst us who think and feel like these zealots referred to above. So long as Sri Lanka holds within it men and women of such a tribal mindset, so long will it remain a blighted country.

It is true that Lakshman Kadirgamar had high political ambitions and that he was keen on becoming prime minister on being approached to don that mantle. He would have, deservedly in my view, been our first Tamil prime minister had plans worked out. In fairness to him, the fact that he did not jockey for the post of prime minister bears repetition. I was then, and am now more so of the view, that the conferment of the prime ministership on Lakshman Kadirgamar, however interim an appointment it might have been, would have been good for Kadirgamar and for Sri Lanka.

I am also confident that had he yet been amongst us after the military defeat of the Tamil Tigers in May 2009, Kadirgamar would have played a cardinal role in recreating a feeling of Sri Lankanness in our society that transcends religion and ethnicity without endangering the multi-faceted personality of our country. His quiet but effective contribution in assisting the government in the restoration of the Jaffna public library is illustrative of the kind of effort he would have put in on behalf of national resuscitation and regeneration.

Lakshman Kadirgamar was ‘a scholar-statesman who was both a realist and idealist’. Despite the deleterious impact of politics on him, his years in our national legislature served to raise the level of political discourse, both at home and abroad, several notches higher. He will be remembered by future generations of Sri Lankans for the values and principles he lived and died for.

Features

Another Christmas, Another Disaster, Another Recovery Mountain to Climb

The 2004 Asian Tsunami erupted the day after Christmas. Like the Boxing Day Test Match in Brisbane, it was a boxing day bolt for Indonesia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, India and Maldives. Twenty one years later, in 2025, multiple Asian cyclones hit almost all the old victims and added a few more, including Malayasia, Vietnam and Cambodia. Indonesia and Sri Lanka were hit hard both times. Unlike the 2004 Tsunami, the 2025 cyclones made landfalls weeks before Christmas, during the Christian Season of Advent, the four-week period before Christmas preparing for the arrival of the Messiah. An ominously adventus manifestation of the nature’s fury.

Yet it was not the “day of wrath and doom impending … heaven and earth in ashes ending” – heavenly punishment for government lying, as an opposition politician ignorantly asserted. By that token, the gods must have opted to punish half a dozen other Asian countries for the NPP government’s lying in Sri Lanka. Or all those governments have been caught lying. Everyone is caught and punished for lying, except the world’s Commander in Chief for lying – Donald J. Trump. But as of late and none too sooner, President Trump is getting his punishment in spades. Who would have thought?

In fairness, even the Catholic Church has banished its old hymn of wrath (Dies irae, dies illa) that used to be sung at funerals from its current Missals; and it has on offer, many other hymns of peace and joy, especially befitting the Christmas season. Although this year’s Christmas comes after weeks of havoc caused by cyclonic storms and torrential rains, the spirit of the season, both in its religious and secular senses, will hopefully provide some solace for those still suffering and some optimism to everyone who is trying to uplift the country from its overflowing waterways and sliding slopes.

As the scale of devastation goes, no natural disaster likely will surpass the human fatalities that the 2004 Tsunami caused. But the spread and scale of this year’s cyclone destruction, especially the destruction of the island’s land-forms and its infrastructure assets, are, in my view, quite unprecedented. The scale of the disaster would finally seem to have sunk into the nation’s political skulls after a few weeks of cacophonic howlers – asking who knew and did what and when. The quest for instant solutions and the insistence that the government should somehow find them immediately are no longer as vehement and voluble as they were when they first emerged.

NBRO and Landslides

But there is understandable frustration and even fear all around, including among government ministers. To wit, the reported frustration of Agriculture Minister K.D. Lalkantha at the alleged inability of the National Building Research Organization (NBRO) to provide more specific directions in landslide warnings instead of issuing blanket ‘Level 3 Red Alerts’ covering whole administrative divisions in the Central Province, especially in the Kandy District. “We can’t relocate all 20 divisional secretariats” in the Kandy District, the Minister told the media a few weeks ago. His frustration is understandable, but expecting NBRO to provide political leaders with precise locations and certainty of landslides or no landslides is a tall ask and the task is fraught with many challenges.

In fairness to NBRO and its Engineers, their competence and their responses to the current calamity have been very impressive. It is not the fault of the NBRO that local disasters could not be prevented, and people could not be warned sufficiently in advance to evacuate and avoid being at the epicentre of landslides. The intensity of landslides this year is really a function of the intensity and persistence of rainfall this season, for the occurrence of landslides in Sri Lanka is very directly co-related to the amount of rainfall. The rainfall during this disaster season has been simply relentless.

Evacuation, the ready remedy, is easier said than socially and politically done. Minister Lal Kantha was exasperated at the prospect of evacuating whole divisional secretariats. This was after multiple landslides and the tragedies and disasters they caused. Imagine anybody seriously listening to NBRO’s pleas or warnings to evacuate before any drop of rainwater has fallen, not to mention a single landslide. Ignoring weather warnings is not peculiar to Sri Lanka, but a universal trait of social inertia.

I just lauded NBRO’s competence and expertise. That is because of the excellent database the NBRO professionals have compiled, delineating landslide zones and demarcating them based on their vulnerability for slope failure. They have also identified the main factors causing landslides, undertaken slope stabilization measures where feasible, and developed preventative and mitigative measures to deal with landslide occurrences.

The NBRO has been around since the 1980s, when its pioneers supplemented the work of Prof. Thurairajah at Peradeniya E’Fac in studying the Hantana hill slopes where the NHDA was undertaking a large housing scheme. As someone who was involved in the Hantana project, I have often thought that the initiation of the NBRO could be deemed one of the positive legacies of then Housing Ministry Secretary R. Paskaralingam.

Be that as it may, the NBRO it has been tracking and analyzing landslides in Sri Lanka for nearly three decades, and would seem to have come of age in landslides expertise with its work following 2016 Aranayake Landslide Disaster in the Kegalle District. Technically, the Aranayake disaster is a remarkable phenomenon and it is known as a “rain-induced rapid long-travelling landslide” (RRLL). In Kegalle the 2016 RRLL carried “a fluidized landslide mass over a distance of 2 km” and caused the death of 125 people. International technical collaboration following the disaster produced significant research work and the start of a five-year research project (from 2020) in partnership with the International Consortium on Landslides (ICL). The main purpose of the project is to improve on the early warning systems that NBRO has been developing and using since 2007.

Sri Lankan landslides are rain induced and occur in hilly and mountainous areas where there is rapid weathering of rock into surface soil deposits. Landslide locations are invariably in the wet zone of the country, in 13 districts, in six provinces (viz., the Central, Sabaragamuwa, Uva, Northwestern, Western and Southern, provinces). The Figure below (from NBRO’s literature) shows the number of landslides and fatalities every year between 2003 and 2021.

Based on the graphics shown, there would have been about 5,000 landslides and slope failures with nearly 1,000 deaths over 19 years between 2003 and 2021. Every year there was some landslide or slope failure activity. One notable feature is that there have been more deaths with fewer landslides and vice-versa in particular years. In 2018, there were no deaths when the highest number (1,250) of landslides and slope failures occurred that year. Although the largest number in an year, the landslides in 2018 could have been minor and occurred in unpopulated areas. The reasons for more deaths in, say, 2016 (150) or 2017 (250+), could be their location, population density and the severity of specific landslides.

NBRO’s landslide early warning system is based on three components: (1) Predicting rainfall intensity and monitoring water pressure build up in landslide areas; (2) Monitoring and observing signs of soil movement and slope instability in vulnerable areas; and (3) Communicating landslide risk level and appropriate warning to civil authorities and the local public. The general warnings to Watch (Yellow), be Alert (Brown), or Evacuate (Red) are respectively based on the anticipated rainfall intensities, viz., 75 mm/day, 100 mm/day; and 150 mm/day or 100 mm/hr. My understanding is that over the years, NBRO has established its local presence in vulnerable areas to better communicate with the local population the risk levels and timely action.

Besides Landslides

This year, the rain has been relentless with short-term intensities often exceeding the once per 100-year rainfall. This is now a fact of life in the era of climate change. Added to this was cyclone Ditwah and its unique meteorology and trajectory – from south to north rather than northeast to southwest. The cyclone started with a disturbance southwest of Sri Lanka in the Arabian Sea, traversed around the southern coast from west to east to southeast in the Bay of Bengal, and then cut a wide swath from south to north through the entire easterly half of the island. The origin and the trajectory of the cyclone are also attributed to climate change and changes in the Arabian Sea. The upshot again is unpredictability.

Besides landslides, the rainfall this season has inundated and impacted practically every watershed in the country, literally sweeping away roads, bridges, tanks, canals, and small dams in their hundreds or several hundreds. The longitudinal sinking of the Colombo-Kandy Road in the Kadugannawa area seems quite unparalleled and this may not be the only location that such a shearing may have occurred. The damages are so extensive and it is beyond Sri Lanka’s capacity, and the single-term capacity of any government, to undertake systematic rebuilding of the damaged and washed-off infrastructure.

The government has its work cutout at least in three areas of immediate restoration and long term prevention. On landslides warning, it would seem NBRO has the technical capacity to do what it needs to do, and what seems to be missing is a system of multi-pronged and continuous engagement between the technical experts, on the one hand, and the political and administrative powers as well as local population and institutions, on the other. Such an arrangement is warranted because the landslide problem is severe, significant and it not going to go away now or ever.

Such an engagement will also provide for the technical awareness of the problem, its mitigation and the prevention of serious fallouts. A restructuring could start from the assignment of ministerial responsibilities, and giving NBRO experts constant presence at the highest level of decision making. The engagement should extend down the pyramid to involve every level of administration, including schools and civil society organizations at the local level.

As for external resources, several Asian countries, with India being the closest, are already engaged in multiple ways. It is up to the government to co-ordinate and deploy these friendly resources for maximum results. Sri Lanka is already teamed with India for meteorological monitoring and forecasting, and with Japan for landslide research and studies. These collaborations will obviously continue but they should be focused to fill gaps in climate predictions, and to enhance local level monitoring and prevention of landslides.

To deal with the restoration of the damaged infrastructure in multiple watershed areas, the government may want to revisit the Accelerated Mahaweli Scheme for an approach to deal with the current crisis. The genesis and implementation of that scheme involved as many flaws as it produced benefits, but what might be relevant here is to approach the different countries who were involved in funding and building the different Mahaweli headworks and downstream projects. Australia, Britain, Canada, China, Italy, Japan, Sweden and Germany are some of the countries that were involved in the old Mahaweli projects. They could be approached for technical and financial assistance to restore the damaged infrastructure pieces in the respective watershed areas where these countries were involved.

by Rajan Philips ✍️

Features

Feeling sad and blue?

Here is what you can do!

Comedy and the ability to have a good laugh are what keep us sane. The good news to announce is that there are many British and American comedy shows posted up and available on the internet.

They will bring a few hours of welcome relief from our present doldrums.

Firstly, and in a class of its own, are the many Benny Hill shows. Benny is a British comedian who comes from a circus family, and was brought up in an atmosphere of circus clowning. Each show is carefully polished and rehearsed to get the comedy across and understood successfully. These clips have the most beautiful stage props and settings with suitable, amusing costumes. This is really good comedy for the mature, older viewer.

Benny Hill has produced shows that are “Master-Class” in quality adult entertainment. All his shows are good.

Then comes the “Not the Nine o’clock news” with Rowan Atkinson and his comedy team producing good entertainment suitable for all.

And then comes the “Two Ronnies” – Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett, with their dry sense of humour and wit. Search and you will find other uplifting shows such as Dave Allen, with his monologues and humour.

All these shows have been broadcast in Britain over the last 50 years and are well worth viewing on the Internet.

Similarly, in The USA of America. There are some really great entertainment shows. And never forget Fats Waller in the film “Stormy Weather,” where he was the pianist in the unforgettable, epic, comedy song “Ain’t Misbehavin”. And then there is “Bewitched” with young and glamorous Samantha Stevens and her mother, Endora who can perform magic. It is amazing entertainment! This show, although from the 1970s was a milestone in US light entertainment, along with many more.

And do not overlook Charlie Chaplin and Laurel and Hardy, and all the Disney films. Donald Duck gives us a great wealth of simple comedy.

The US offers you a mountain of comedy and good humour on Youtube. All these shows await you, just by accessing the Internet! The internet channel, ‘You tube’ itself, comes from America! The Americans reach out to you with good, happy things right into your own living room!

Those few people with the ability to understand English have the key to a great- great storehouse of uplifting humour and entertainment. They are rich indeed!

by Priyantha Hettige

Features

Lalith A’s main enemy was lack of time and he battled it persistently

Presidential Mobile Service at Matara amid JVP terror

Like most Ministers, Mr. Athulathmudali over programmed himself. In this respect his was an extreme case. He was an early riser and after his morning walk and the usual routines of a morning, was ready for business by 6.30 a.m. In fact he once shocked an IMF delegation by fixing the appointment with it at this hour. The delegation had to be persuaded that they had heard right, and that the appointment was indeed for 6.30 a.m. and not 6.30 p.m. This desire to get through much as possible during a day inevitably led to certain imbalances. Certain matters which needed more time did not get that time, whilst at the level of officials, we felt that we needed more time with him, and quality time at that.

I had spoken to him several times on this subject. He always had good intentions and wanted to give us more time. But with his political, social and even intellectual responsibilities in regard to speaking engagements of a highly professional nature, it was not often possible to find this time. This situation was highlighted in a comic way, when one day on hearing that the minister had arrived in office for a short time, I grabbed some important papers which I wanted to discuss with him, and made for his room. When I entered, I found three officers, with files in their hands milling outside the door of the washroom. The minister was inside.

I suggested that we might as well form a queue outside the door, a queue which I also joined. An official who came after me also joined the queue. When the minister opened the door, to his great astonishment, and then to his amusement, he found five senior officials, including his Secretary lined up outside the bathroom door! It was funny and we made it funny. But the underlying intentions were quite serious, and we wanted to send him a message that we wanted more time with him. We had to however grab moments such as these in order to keep the flow of work going.One day he good humouredly said, “You all swamp me as I come in,” to which I lightly replied “As a distinguished lawyer you should know that possession is nine-tenths of the law, and now we are in possession of both your room and your attention.” Mr. Athulathmudali chuckled.

An important requirement under Mr. Athulathmudali was a report that had to be submitted to him if any official under his Ministry went abroad on official business. The report had to be reasonably brief, more analytical than descriptive and wherever possible or relevant contain specific recommendations in regard to the betterment of the officer’s area of work. Since the Ministry was quite large, a considerable number of officials went abroad for seminars, study tours, research collaboration, conferences, negotiations and so on. There were, therefore a significant number of reports coming to him. Many of these he read, and on some, he commented or asked questions or sought clarifications. What amazed us was how he found the time. His main enemy was time and he battled it with persistence and determination. Most of us were also in a similar position, and in this, his powerful example was a source of encouragement.

Duties not quite pleasant

As mentioned in several places in these memoirs, a senior public servant’s or a Secretary’s job is not always a pleasant one. At the level of the hierarchy of officials the buck stops with you. Thereafter, when necessary, battling the minister becomes your business. I used to insist to my officials that I needed a good brief. I was not prepared to go and start an argument with a minister unless I was in possession of the full facts. Interpretation was my business. But I needed verifiable facts and authentic figures. Officers who worked with me were soon trained to comply with these requirements. After that was done, if there was any flak, it was my business to take it upon myself. On one such occasion, I had to speak rather firmly to the acting Minister, Mr. G.M. Premachandra. He was young, energetic and even aggressive and was somewhat of a “stormy petrel.” He was an effective speaker in the Sinhala e and could be a formidable debater.

When he became State Minister for Food, he took it upon himself to probe everything. He started getting involved in administrative matters, the implications of which he did not understand, and the details of which he had no time for. During the course of these he not only started criticizing officials liberally, but also employed innuendo to suggest that they were corrupt. When interested parties got to know this, they fed him with halftruths and sometimes plain lies. This naturally confirmed the suspicions in his own mind. He blindly felt around and got hold of some tail and thought that was the elephant. The State Secretary, Mr. Sapukotana, an experienced and balanced official tried his best to advice the minister of the consequences of his actions.

Senior officials in the Food Department were being kept off balance much of the time. Paralysis as creeping into the decision making process. No one was taking decisions because taking decisions risked misinterpretation, suspicion and innuendo. The Deputies were pushing papers up to the Food Commissioner, and soon the Food Commissioner was pushing papers up to the State Secretary. Matters were getting really serious, because delays in calling for and deciding on tenders, attending to commercial disputes and so on were bound to have a serious effect on the availability of timely food supplies, and the maintaining of food security.

Mr. Sapukotana kept me informed from time to time of the developing situation. He tried his best to handle it without disturbing me. But it gradually came to a point that we were both of the view that my intervention was necessary. I took an opportunity that presented itself after a “mini cabinet” meeting which Mr. Premachandra chaired as Acting Minister. I asked him whether he would stay back for a moment. His Secretary seemed embarrassed to stay, but I asked him also to sit. Thereafter, I politely but firmly explained to the minister, the consequences of his actions.

I asked him whether he was aware that nobody was prepared to take a decision in the food sector. I pointed out that should disaster strike, Minister Athulathmudali would certainly ask him for an explanation. I told him further, that in such a contingency, that we as officials will have to tell the truth to the minister. The acting minister listened in silence. I wondered as to what forces of counter attack were gathering in his breast. He did not have the reputation of bowing meekly to a challenge and here I was calling into question his entire approach to his work.

Ultimately when he spoke, he said something that we least expected and which took us completely by surprise. He said that he listened carefully to me; he said that until now he had not realized the gravity of the situation that his actions were precipitating. Then to my great astonishment he said: “You have given me advice like a parent, like a father. Even parents don’t always give such good advice. I will act according to your advice.” Mr. Sapukotana and I were rendered speechless. This was one more of the many experiences I had in public service, where the totally unexpected had occurred.

Through my experience I have been convinced that one should not shirk one’s duty to advice ministers. This duty has to be performed in the public interest and one should not be deterred by possible consequences. However, there is a way and manner of giving this advice. One has to be polite. One should not adopt a confrontational attitude. In my experience, some of these “consequences” which people fear are more imagined than real, and ministers and politicians do not always act according to their perceived public characteristics. On this occasion Mr. Premachandra was a case in point.

Presidential Mobile Service – Matara

The second Presidential Mobile Service was to be held at Matara on November 3, 1989. This was a time of intense JVP activity when the country was gripped by fear. The decision to hold the service in Matara in the deep south was it a sense a challenge to the JVP. Rumours were rife that they would disrupt activities. We were to leave during the early morning of Nov. 3 and this itself was scary. In fact the country had reached a stage where there was very little traffic on the roads after about 9 p.m. We had now to leave for Matara to face an unknown situation leaving home around 4.30 in the morning.

When we left, we noticed that there was hardly any traffic on the roads. All around was in pitch darkness. Even some of the street lights were not functioning. It was quite eerie. We made our way past numerous check points at a couple of which we were stopped.

All this was not a comfortable experience. One felt apprehension. I was booked at the Weligama rest house but when I reached it I found that the power had been disrupted by the JVP during the previous night. We would have to be without lights or fans. But what was far worse was that the disruption of power had affected the pumping of water and the toilets could not be flushed.

The rest house was in short uninhabitable. The authorities there informed us that power would be restored by evening. But none of us had confidence that this would be done or if done, that it would not be disrupted again during the night. Some of us therefore decided to make alternative arrangements, which were not easy to make. Most of the hotels in the vicinity of Matara and even somewhat beyond had already been booked. Eventually, after a diligent search and with the assistance of friends, I found myself a room at Koggala Beach hotel.

This was an immense relief. In fact, it turned out to be much more than mere relief because of the interesting crowd of public servants in occupation. They were a jolly group of story tellers who had a variety of the most hilarious anecdotes to retail, which spared no one. When we reached the hotel at the end of a tiring day, we were able to forget the grim reality outside. Perhaps we really needed to laugh our cares away. Most of us had been subjected to considerable strain for a significant period of time.

At the mobile service itself in the Rahula College premises where the service was held was almost completely deserted on the first day. People were afraid to defy a JVP ban on attending. On the second day however the dam burst. People flocked in from all quarters and directions jamming the space and facilities available. Long queues formed outside areas allocated to all Ministries. The people themselves had suffered due to the disruption of their lives and activities, and when some relief seemed available, one day was all they could contain themselves however dire the threat. They voted with their feet.

On that second day we couldn’t finish at 5 p.m. There were so many people that hours were extended till 6.30 p.m. By the time we got back to our hotels, it was well past 8 p.m. Usually, the third day of the service was a half day, where we finished by 1 p.m., had lunch and started for home. But because of the lost first day and the crowds, the third day was extended to 5 p.m. But that was the official time. Many of us were stuck till about 7 p.m. We did not want to abandon the people still in the queue and who were now looking pretty desperate that they would not be attended to. They had suffered much. This meant once again traveling in the dark, this time to get home.

(Excerpted from In Pursuit of Governance, autobiography of MDD Peiris)

-

Midweek Review5 days ago

Midweek Review5 days agoHow massive Akuregoda defence complex was built with proceeds from sale of Galle Face land to Shangri-La

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoPope fires broadside: ‘The Holy See won’t be a silent bystander to the grave disparities, injustices, and fundamental human rights violations’

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoPakistan hands over 200 tonnes of humanitarian aid to Lanka

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoBurnt elephant dies after delayed rescue; activists demand arrests

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoUnlocking Sri Lanka’s hidden wealth: A $2 billion mineral opportunity awaits

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoColombo Port facing strategic neglect

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoArmy engineers set up new Nayaru emergency bridge

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoSri Lanka, Romania discuss illegal recruitment, etc.