Features

Selling Oil, motor racing and moving from Shell to Reckitt and Colman

Excerpted from the memoirs of

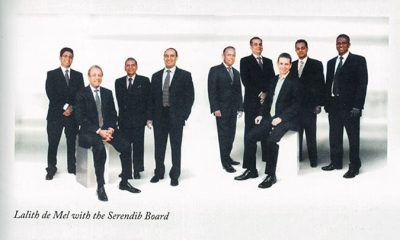

Lalith de Mel

His first real job was with the Shell Company of Ceylon Ltd. Which her joined at age 22. The Research Economist role at the Coconut Research Institute was almost a continuation of life at Cambridge. Academic research at one’s own pace was close to preparing a piece of work for the supervisor.

Shell was a proper job. He had a boss, and he had to accomplish whatever his boss wanted him to do in an industry and in activity that was far removed from Economics. It was new territory, marketing petroleum products. It was his first encounter with petroleum and his first encounter with marketing, but he settled easily into the world of commerce.

His first role at Shell was working directly for the Head of Marketing as his Personal Assistant. He was an experienced petroleum man and a rather unfriendly Egyptian national. His core role for Lalith was having him prepare feasibility studies on building new filling stations.

Shell worked a half day on Saturdays, and Mike Khoury (that was his name) would give him an assignment around 11 a.m. and insist that he gets the report the same day. He did this regularly and justified it by saying that it was only on Saturday afternoons that he had the time to study investment projects. Lalith grudgingly says that this was probably true.

After his stint as a PA he was given responsibility for marketing kerosene and reporting to an Iraqi national. The man was happy to not exert himself unduly and probe the rural markets and to leave it all to Lalith. He was pleased that as a 22-year-old he was virtually responsible for marketing kerosene, which was perceived as a product with good growth potential. It was the main source of lighting in rural areas and the task was to persuade housewives to move from firewood to kerosene for cooking.

He enjoyed the opportunity of traveling all over the rural areas. It was perhaps this understanding of rural areas that has triggered his firm belief in the need to develop rural areas, on which theme he has written many articles.

From kerosene, he became a part of the Retail Marketing team. That was the engine room that drove sales of Shell products. Shell was one of the key retailers of petroleum products worldwide. The main competitors globally were equally big boys. Market share varied. The way Shell International ensured consistency in approach across the world was by having detailed process manuals for all parts of the marketing mix. The local companies had to develop their campaigns within the lines set by the process manuals. It was a wonderful course in structured marketing. He says it was like doing a marketing degree and freely admits that he learned his marketing at Shell.

After a few years, he was moved to the Finance Division. He had twin roles. In addition to carrying out a normal accounting function, he worked in the special unit created to study the options for formulating claims for compensation for assets that were taken over by the Government when Shell and the other oil companies were partly nationalized. He quickly became head of this unit and his last role was in putting together the claims for compensation on the agreed format, signing on behalf of Shell and submitting the claims to the Government.

Shell was keen that he should continue his lectures at Aquinas, and he continued to teach students studying for the BSc London University Economics degree in the evenings.

Outside work, Shell was a fun place. It had an excellent sports ground. He got into the cricket team that was in the A division of the Mercantile league. He also played badminton and hockey in the inter-firm tournaments. Shell took a keen interest in motor racing. The objective was to get the top drivers to use Shell petrol and Shell oil. Dudley Perera, a very Senior Manager at the time, was the link man between Shell and motor racing and Lalith became his assistant.

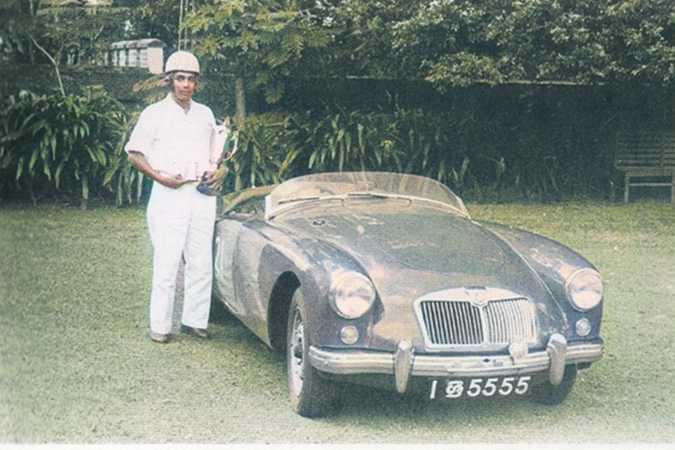

The atmosphere at motor race meets, the roar from the cars, the smell of burning oil and the vibes from screeching tyres got to him and he started motor racing. He drove a red MGA with the distinctive number plate I SRI 5555. He raced for many years and had his share of wins both at Katukurunda and the Mahagastota Hill Climb in Nuwara Eliya. In one event at Katukurunda, he raced with Upali Wijewardene, his Cambridge University friend and subsequent famous entrepreneur, and Asoka Gopallawa, the son of the Governor General, all driving MGAs.

How Shell plans management succession

“After five years at Shell, I felt the urge to move on. There was uncertainty about the future, with partial nationalization of the petroleum industry. The exciting future appeared to be in the new foreign investments to set up the manufacturing industry.

When I sent in my resignation, I was summoned by the General Manager, a Dutchman named Jan Van Reeven. He did not want me to go as they had identified me as a potential International General Manager. I probably had a bemused expression on my face and so Van Reeven said, `Let me explain.’ He said that Shell had over 100 operating companies around the world and they had 100 General Managers, some would move to other companies, some would get fired and the rest would eventually retire at some stage in the future. So he said it was a continuous process in Shell companies to identify potential future General Managers and to develop suitable career paths for them that would eventually lead to a General Manager post in the future.

The process, he explained, was for operating Shell companies to seek and recruit outstanding persons as management trainees from time to time. The new trainee’s first job is to work for one of the directors as a Personal Assistant. At the end of this period, an early call is made as to whether the person is a potential future GM. If the answer is yes, the trainee is given a challenging career path and reassessed at the end of each year.

`As your preferred path was Marketing, you were given various marketing roles,’ Van Reeven explained. After three years the Shell approach was to test the trainee in a different discipline. “That’s why you were transferred to Finance as an Accountant.’ He then said: ‘After five years, we were convinced you would be a future GM and our development plan is to transfer you to the international pool as an employee of Shell International and transfer you to a Shell Company overseas.’

I was having a great social life in Colombo and had no desire to go and work abroad. 1 thanked him for the excellent training I had at Shell and said all the appropriate nice things about Shell and Van Reeven and then said I was firmly committed to pursuing a Marketing career in a consumer goods company. He was very gracious and wished me well and as I got up to leave he said, ‘Someone I know is setting up a multinational manufacturing company and he wants a marketing man; would you like to meet him?’ I said yes and he sent me to meet Alex Alexander, the Managing Director of Reckitt & Colman of Ceylon, who was setting up the business. He offered me the Marketing Manager role. I accepted, and that was the start of my journey with Reckitt & Colman.”

He was marketing manager of Reckitts at age 27 and a director of that company at 29-years.

Shell always had a big advertising budget. Their agency was Grants, then headed by Reggie Candappa and his assistant was Anandatissa de Alwis, who later became Minister of State and the Speaker. Later on in life he started his own agency, De Alwis Advertising. Lalith said: “They both became good lifelong friends. I signed them on and they became our advertising agents at Reckitt & Colman. They deserve a good part of the credit for the excellent sales performance of the string of brands we launched.”

The first Marketing Manager of Reckitt & Colman of Ceylon was Michael Morris. He had been with the Indian business for a few years and came to help to set up the new business in Sri Lanka. He was in Sri Lanka for a relatively short period; he decided to go back to the UK as his wife was a doctor and wanted to go back into medical practice. This created the vacancy for which he was recruited. Morris later became a Member of the British Parliament and Deputy Speaker and was then ennobled to become Lord Naseby. He was recently in the news about war crimes in Sri Lanka. He continues to be a good friend.

Two Englishmen had been sent to start the business, Alex Alexander as Managing Director and Peter Crisp as Factory Manager. All the hard work was at the manufacturing end. Disprin was being manufactured for the first time outside the UK. A whole host of previously imported products were progressively locally manufactured.

The excitement of getting a job as a Marketing Manager of consumer products in a multinational company was short-lived. He soon felt it was a well-paid non-job with nothing to do by afternoon. The Reckitt’s products were distributed by E.B. Creasy & Co. and the Goya range by Lalvani Brothers; the advertisements were sent from the UK. All the advertisements were ones used by the group in the UK. All he had to do was send them to the advertising agency.

After a few months he assessed the scene and made his move. It was brave, reckless or foolish. He had never marketed any consumer products, knew nothing about the Pettah wholesale market which controlled 50% of sales and had never managed a sales force. He was good with numbers and knew how to put together convincing project proposals (learnt the hard way at Shell).

He formulated a proposal to terminate the distribution agreements, to set up his own marketing office and to recruit a sales force, a product manager and an advertising manager. In his proposal, he demonstrated that the commissions paid to the two distributors would more than cover the cost and in fact make a significant contribution to profits. The MD Alexander was impressed with the proposal and bought into the idea. He had just asked one question: “Are you sure you can do it?” When Lalith said “yes,” Alexander had said, “Okay, go and do it.”

He did not quite know how he was going to do it. There were many things he had not done before but he was certain that he could do them. As subsequent events will show, this was a trait he carried right through his life. He persuaded Terrence de Silva who had worked for him at Shell to join him as the Manager for everything – HR, admin, credit control, managing the fleet of vans, etc. Terrence was with him as a part of the team until he left for England. Terrence was the engine room of the Marketing division and kept everything running smoothly, whilst he launched and developed a great basket of products.

They had an amazing array of products, such as Disprin, Dettol, Brasso, Silvo, Robin Blue, Harpic, Mansion polish, Cobra shoe polish and the Goya range of fragrance products such as perfumes, colognes, talc and soap. One by one they were rolled on to the market and it was a great challenging time for him.

Fortunately it all worked out well, the sales grew, there were no bad debts, which was always a risk with the Pettah wholesale market, the profits grew and the business was highly successful and profitable. The overseas investors were pleased.

Basil Reckitt’s visit

There is a story that must be told. Basil Reckitt, the Chairman of Reckitt & Colman UK, came for the formal opening, which was also attended by Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, as it was the first major foreign investment in Sri Lanka during her tenure as the Prime Minister.

They were seated next to each other and chatting and she asked Basil Reckitt whether there was anything that she could do and he said, “Please could we have a telephone?” Those were the days when it was impossible to get a telephone. When Lalith became the Chairman of Sri Lanka Telecom later on, his objective was to make sure that anybody who wanted a telephone would get one within a week and by the time he left his role this objective had been achieved.

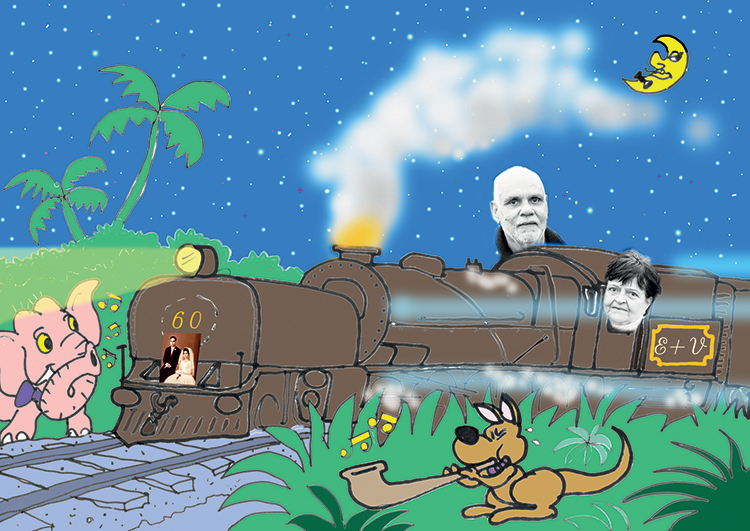

Marriage

In 1966, whilst he was busy building the business, he also got married. His wife was then an undergraduate at the University of Colombo and she had to continue her studies to complete her degree. After she graduated, she started working in the university itself Since she was studying, they did not have a much of social life in the evenings, so he thought it would be useful to do some studying himself and he started studying Accountancy. He completed the intermediate exams of Cost and Works Accountants, the precursor of CIMA, and also did the exams to become an Associate of the Institute of Book Keepers. When his wife graduated and was no longer poring over books in the evening, he stopped his studies. However what he had learned proved to be very helpful as it helped him to develop a good understanding of finance and accounting.

Managing Directors

Alex Alexander moved on to another part of the Group and was followed by Mark Foster, who was also a Cambridge graduate. When Mark moved on, he was followed by Greg Courtier, who became his third British boss. He did not resent this as that was the style back then, where all foreign firms had a foreigner as the Managing Director.

He was asked to say something in his own words about his key achievements and his relationship with his foreign bosses during this period. Multinationals controlled their businesses from Head Office. The local Managing Director reported to a Regional Director at Corporate Headquarters. There were very specific guidelines on what required approval from HQ

“All advertisements were sent from the UK. For the local language press we had to translate the English ads. After my spell at Shell, I appreciated that multinationals wanted to preserve the brand footprint and have the same consistent message all over the world. The challenge was to wriggle some freedom within this constraint in order to create better advertising that was more relevant in the context of the local market. After a long exchange of correspondence, I succeeded in getting approval to create our own ads.

I had to stay within the parameters of the global branding footprint but was given freedom on how to convey this in local media. We were probably the first Reckit’s market in the Commonwealth to win

this concession. I also got approval to shift the positioning of Dettol from solely a treatment for cuts and wounds to a personal care product that prevented infection. I pursued this right through my career and created a mega global brand in developing countries that is still growing. Dettol is

amazing marketing story as nobody has seen germs or seen Dettol kill germs, but were made to believe that it did provide protection from germs.Both Mark Foster and Greg Courtier were marketers, but they knew nothing about how to market and advertise products in Ceylon. They thought it prudent not to interfere with me and I had the freedom to operate in effect without a boss in the Colombo office whilst the MD worked out of the factory and office at Ratmalana. The challenge in a multinational is getting this freedom.

The UK office was pleased with the results and naturally the MD got the credit for the good sales and profits growth. I made no claims for any credit from our lords and masters in the UK for the good results. When the Head Office staff visited the business, I made it a point to say as many times as possible how much I enjoyed working with Mark/ Greg and said I greatly valued their guidance. It was true I enjoyed working with them because they did not interfere. As for guidance it was not true, and they were not really able to provide any meaningful guidance.

But strategically it was a good thing to say, so this led to a good partnership with the Managing Director. Not getting the credit and warm congratulations from the parent company was a small price to pay for having complete freedom. I steered well clear of the pitfall of trying to get plaudits for the company performance from the overseas owners and getting into a competition for praise with the boss and thereby having a not-so-congenial relationship with him.

I had a gut feeling that payback time would come. They were possibly slightly embarrassed to take the credit for my sales and profits results and had to do something to acknowledge my contribution. They recommended that I be made a Director of the Ceylon Company, which was a public quoted company.

I was pleased and content. That was as far as one’s aspirations went in those days, to become a director of a local multinational company. There was no ambition to go any further, because less foreign firms were likely to always have a foreigner as the head of their business.

The Government formed a new company named Consolidated Exports and it came to be called Consolexpo. This was a joint public sector-private sector partnership to generate and support the growth of exports. I was flattered and pleased when I was invited to join the Board. This was my first experience with the Government sector. It was also my first Board appointment outside Reckitt & Colman, so I count this as one of my achievements during this period.

Then one day a visiting director from the parent company called me in for a chat. He said they had been following my progress and were pleased with what they saw. He said almost casually that I might have the chance of being the first Sri Lankan Managing Director, but added in the same breath that I would have to prove myself in another market. I impulsively asked whether I could be sent to Australia. Half my vintage Josephian rugger team and all my Burgher school friends had migrated to Melbourne. I thought if I had a spell in Australia I could have a whale of a time with my old buddies.

The visiting Director said, ‘We will let you know in due course’ and eventually they told me that they had decided I should go and work in Brazil as a member of the management team of that company. That was their biggest business in South America and it was a huge market. Brazil was five times the size of India.

Features

The State of the Union and the Spectacle of Trump

President Donald J. Trump, as the American President often calls himself, is a global spectacle. And so are his tariffs. On Friday, February 20, the US Supreme Court led by Chief Justice John Roberts and a 6-3 majority, struck down the most ballyhooed tariff scheme of all times. Upholding the earlier decisions of the lower federal courts, the Supreme Court held that Trump’s use of ‘emergency powers’ to impose the so called Liberation Day tariffs on 2 April 2025, is not legal. The Liberation Day tariffs, which were comically announced on a poster board at the White House Rose Garden, is a system of reciprocal tariffs applied to every country that exported goods and services to America. The court ruling has pulled off the legal fig leaf with which Trump had justified his universal tariff scheme.

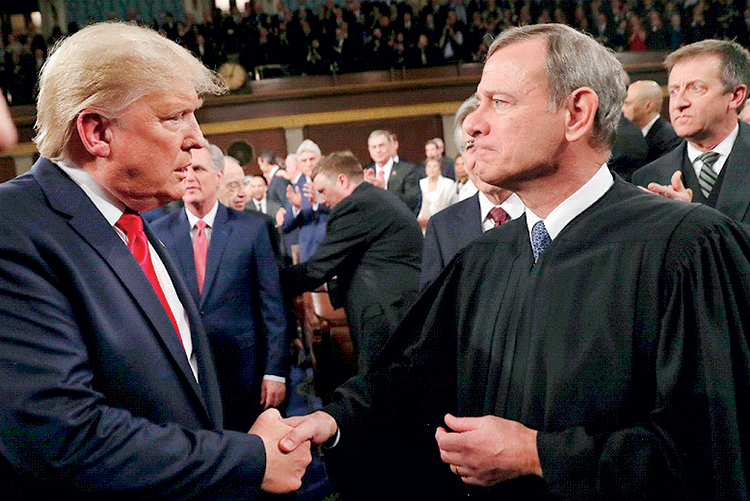

Trump was livid after the ruling on Friday and invectively insulted the six judges who ruled against Trump’s tariffs. There was nothing personal about it, but for Trump, the ever petulant man-boy, there isn’t anything that is not personal. On Tuesday night in Washington, Trump delivered his first State of the Union address of his second presidency. The Chief Justice, who once called the State of the Union, “a political pep rally,” attended the pomp and exchanged a grim handshake with the President.

Tuesday’s State of the Union was the longest speech ever in what is a long standing American tradition that is also a constitutional requirement. The Trump showmanship was in full display for the millions of Americans who watched him and millions of others in the rest of world, especially mandarins of foreign governments, who were waiting to parse his words to detect any sign for his next move on tariffs or his next move in Iran. There was nothing much to parse, however, only theatre for Trump’s Republican followers and taunts for opposing Democrats. He was in his usual elements as the Divider in Chief. There was truly little on offer for overseas viewers.

On tariffs, he is bulldozing ahead, he boasted, notwithstanding the Supreme Court ruling last Friday. But the short lived days of unchecked executive tariff powers are over even though Trump wouldn’t let go of his obsessive illusions. On the Middle East, Trump praised himself for getting the release of Israeli hostages, dead or alive, out of Gaza, but had no word for the Palestinians who are still being battered on that wretched strip of land. On Ukraine, he bemoaned the continuing killings in their thousands every month but had no concept or plan for ending the war while insisting that it would not have started if he were president four years ago.

He gave no indication of what he might do in Iran. He prefers diplomacy, he said, but it would be the most costly diplomatic solution given the scale of deployment of America’s fighting assets in the region under his orders. In Trump’s mind, this could be one way of paying for a Nobel Prize for peace. More seriously, Trump is also caught in the horns of a dilemma of his own making. He wanted an external diversion from his growing domestic distractions. If he were thinking using Iran as a diversion, he also cannot not ignore the warnings from his own military professionals that going into Iran would not be a walk in the park like taking over Venezuela. His state of mind may explain his reticence on Iran in the State of the Union speech.

Even on the domestic front, there was hardly anything of substance or any new idea. One lone new idea Trump touted is about asking AI businesses to develop their own energy sources for their data centres without tapping into existing grids, raising demand and causing high prices and supply shortages. That was a political announcement to quell the rising consumer alarms, especially in states such as Michigan where energy guzzling data centres are becoming hot button issue for the midterm Congress and Senate elections in November. Trump can see the writing on the wall and used much of his speech to enthuse his base and use patriotism to persuade the others.

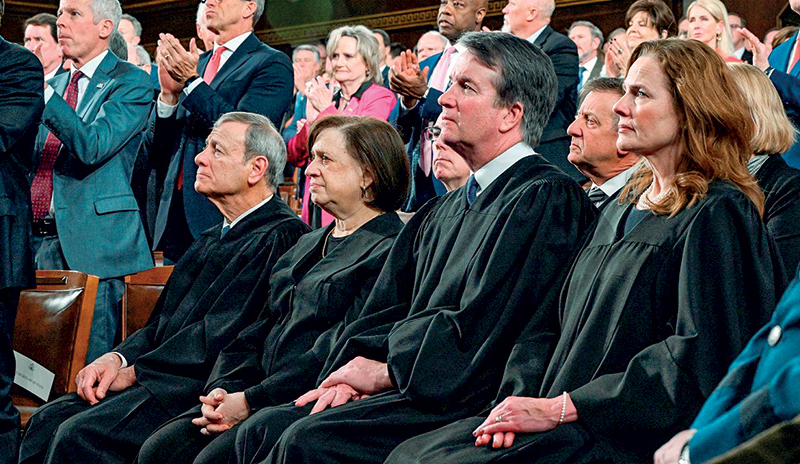

Political Pep Rally: Chief Justice John G. Roberts sits stoically with Justices Elena Kagan, Bret Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett, as Republicans are on their feet applauding.

Although a new idea, asking AI forces to produce their own energy comes against a background of a year-long assault on established programs for expanding renewable energy sources. Fortunately, the courts have nullified Trump’s executive orders stopping renewable energy programs. But there is no indication if the AI sector will be asked to use renewable energy sources or revert to the polluting sources of coal or oil. Nor is it clear if AI will be asked to generate surplus energy to add to the community supply or limit itself to feeding its own needs. As with all of Trump’s initiatives the devil is in the details and is left to be figured out later.

The Supreme Court Ruling

The backdrop to Tuesday’s State of the Union had been rendered by Friday’s Supreme Court ruling. Chief Justice Roberts who wrote the majority ruling was both unassuming and assertive in his conclusion: “We claim no special competence in matters of economics or foreign affairs. We claim only, as we must, the limited role assigned to us by Article III of the Constitution. Fulfilling that role, we hold that IEEPA (International Emergency Economic Powers Act) does not authorize the President to impose tariffs.”

IEEPA is a 1977 federal legislation that was enacted during the Carter presidency, to both clarify and restrict presidential powers to act during national emergency situations. The immediate context for the restrictive element was the experience of the Nixon presidency. One of the implied restrictions in IEEPA is in regard to tariffs which are not specifically mentioned in the legislation. On the other hand, Article 1, Section 8 of the US Constitution establishes taxes and tariffs as an exclusively legislative function whether they are imposed within the country or implemented to regulate trade and commerce with other countries. In his first term, Trump tried to impose tariffs on imports through the Congress but was rebuffed even by Republicans. In the second term, he took the IEEA route, bypassing Congress and expecting the conservative majority in the Supreme Court to bail him out of legal challenges. The Court said, No. Thus far, but no farther.

The main thrust of the ruling is that it marks a victory for the separation of powers against a president’s executive overreach. Three of the Court’s conservative judges (CJ Roberts, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett) joined the three liberal judges (all women – Sonia Sotomayor, Elana Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson) to chart a majority ruling against the president’s tariffs. The three dissenters were Brett Kavanugh, who wrote the dissenting opinion, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett were appointed by Trump. Trump took out Gorsuch and Barrett for special treatment after their majority ruling, while heaping praise on Kavanaugh who ruled in favour of the tariffs. Barrett and Kavanaugh attended the State of the Union along with Roberts and Kagan, while the other five stayed away from the pep rally (see picture).

The Economics of the Ruling

In what was a splintered ruling, different judges split legal hairs between themselves while claiming no special competence in economics and ruling on a matter that was all about trade and economics. Yale university’s Stephen Roach has provided an insightful commentary on the economics of the court ruling, while “claiming no special competence in legal matters.” Roach takes out every one of Trump’s pseudo-arguments supporting tariffs and provides an economist’s take on the matter.

First, he debunks Trump’s claim that trade deficits are an American emergency. The real emergency, Roach notes, is the low level of American savings, falling to 0.2% of the national income in 2025, even as trade deficit in goods reached a new record $1.2 trillion. America’s need for foreign capital to compensate for its low savings, and its thirst for cheap imported goods keep the balance of payments and trade deficits at high levels.

Second, by imposing tariffs Trump is not helping but burdening US consumers. The Americans are the ones who are paying tariffs contrary to Trump’s own false beliefs and claims that foreign countries are paying them. 90% of the tariffs have been paid by American consumers, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Small businesses have paid the rest. Foreign countries pay nothing but they have been making deals with Trump to keep their exports flowing.

According to published statistics, the average U.S. applied tariff rate increased from 1.6% before Trump’s tariff’s to 17%, the highest level since World War II. The removal of reciprocal tariffs after the ruling would have lowered it to 9.1%, but it will rise to 13% after Trump’s 15% tariffs. The registered tariff revenue is about $175 billion, 0.6% of U.S. gross domestic product. The tariff monies collected are legally refundable. The Supreme Court did not get into the modalities for repayment and there would be multiple lawsuits before the lower courts if the Administration does not set up a refunding mechanism.

Lastly, in railing against globalization and the loss of American industries, Trump is cutting off America’s traditional allies and trading partners in Europe, Canada and Mexico who account for 54% of all US trade flows in manufactured goods. Cutting them off has only led these countries to look for other alternatives, especially China and India. All of this is not helping the US or its trade deficit. The American manufacturers (except for sectoral beneficiaries in steel, aluminum and auto industries), workers and consumers are paying the price for Trump’s economic idiosyncrasies. As Roach notes, the Court stayed away from the economic considerations, but by declaring Trump’s IEEPA tariffs unconstitutional, the Court has sent an important message to the American people and the rest of the world that “US policies may not be personalized by the whims of a vindictive and uninformed wannabe autocrat.”

by Rajan Philips

Features

The Victor Melder odyssey: from engine driver CGR to Melbourne library founder

He celebrated his 90th birthday recently, never returned to his homeland because he’s a bad traveler

(Continued from last week)

THE GARRAT LOCOS, were monstrous machines that were able to haul trains on the incline, that normally two locos did. Whilst a normal loco hauled five carriages on its own, a Garrat loco could haul nine. When passenger traffic warranted it and trains had over nine carriages or had a large number of freight wagons, then a Garret loco hauled the train assisted by a loco from behind.

When a train was worked by two normal locos (one pulling, the other pushing) and they reached the summit level at Pattipola (in either direction), the loco pushing (piloting) would travel around to the front the train and be coupled in front of the loco already in front and the two locos took the train down the incline. With a Garraat loco this could not be done as the bridges could not take the combined weight. The pilot loco therefore ran down single, following THE TRAIN.

My father was stationed at Nawalapitiya as a senior driver at the time, and it wasn’t a picnic working with him. He believed in the practical side of things and always had the apprentices carrying out some extra duties or the other to acquaint themselves with the loco. I had more than my fair share.

After the four months upcountry, we were back at Dematagoda on the K. V. steam locos. From the sublime to the ridiculous, I would say after the Garret locos upcountry. Here the work was much easier and at a slower pace, as the trains did not run at speed like their mainline counterparts. The last two months of the third year saw us on the two types of diesel locos on the K.V. line, the Hunslett and Krupp diesels, which worked the passenger trains. For once this was a ‘cushy, sit-down’ job, doing nothing exciting, but keeping a sharp lookout and exchanging tablets on the run. The third year had come to an end and ‘the light at the end of tunnel was getting closer’.

The fourth year saw us all at the Diesel loco shed at Maradana, which was cheek by jowl with the Maradana railway station. The first three months we worked with the diesel mechanical fitters and the following three months with the electrical fitters. Heavy emphasis was placed on a working knowledge of the electrical circuits of the different diesel locos in service, to ensure the drivers were able to attend to electrical faults en-route and bring the train home. This was again a period of lectures and demonstrations

We also spent three months at the Ratmalana workshops, where the diesels were stripped down to the core and refitted after major repairs, to ensure we had a look at what went on inside the many closed and sealed working parts. This was again a 7.00am to 4.00pm day job. Back again at the Diesel shed, Maradana, saw us riding as assistants for the next three months on all the diesel locos in service – The Brush Bragnal (M1), General Electrical (M2), Hunslett locos (G2) and Diesel Rail Cars.

After the final written test on Diesel locos, we began our fifth and final year, which was that of shunting engine driver. The first six months were spent at Maligawatte Yard on steam shunting locos and the next three months shunting drivers on the diesel shunting locos at Colombo goods yard. The final three months were spent as assistants on the M1 and M2 locos working all the fast passenger and mail trains.

I was finally appointed Engine Driver Class III on July 6, 1962, as mentioned earlier I lost eight months of my apprenticeship due to being ill and had to make up the time. This appointment was on three years’ probation, on the initial salary of the scale Rs 1,680 – 72 – Rs 2,184, per annum.

Little did the general traveling public realize that they had well trained and qualified engine drivers working their trains to time Victor was stationed in Galle until December 1967, when he resigned from the railway to migrate to Melbourne, Australia to join the rest of his family. He was the last of 11 siblings to leave Ceylon. Their two elder children were born in Galle. Victor and Esther had three more children in Australia. The children, three boys and two girls) were brought up with love and devotion. They have seven grandchildren and two great grandchildren. They meet often as a family.

He worked for the Victorian State Public Service and retired in 1993 after 25 years’ service. At the time of retirement, he worked for the Ministry for Conservation & Environment. He held the position of Project Officer in charge of the Ministry’s Procedural Documents.

He worked part-time for the Victorian Electoral Office and the Australian Electoral Office, covering State and Federal Elections, from 1972 to 2010. From 1972 to 1982 and was a Clerical Officer and then in 1983 was appointed Officer-in-Charge, Lychfield Avenue Polling Booth, Jacana which is my (the writer’s) electorate.

As part of serving the community Victor participated in a number of ways, quite often unremunerated. He worked part-time for the Department of Census & Statistics, and worked as a Census Collector for the Census of 1972, 1976, 1980 and then Group Leader of 16 Collectors in his area for the 1984, 1988, 1992, 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008 and 2012.

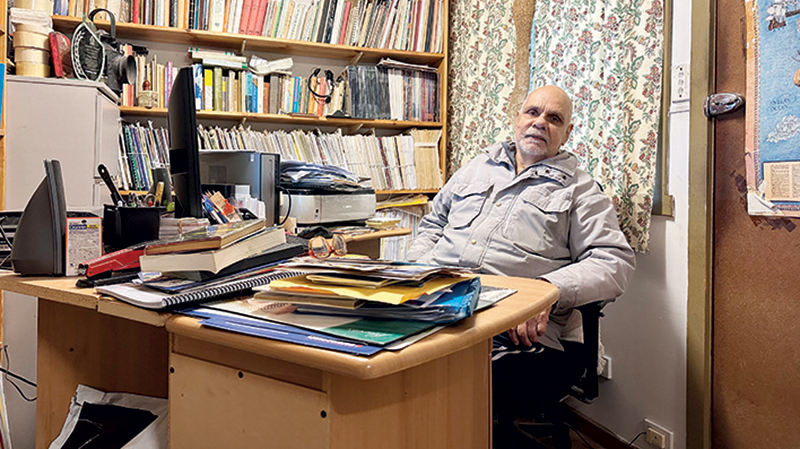

In 1970, Victor began this library, now known as the ‘Victor Melder Sri Lanka Library’, for the purpose of making Sri Lanka better known in Australia. On looking back he has this to say: “Forty-five years later, I can say that it is serving its purpose. In 1993 President Ranasinghe Premadasa of Sri Lanka bestowed on me a national honor – ‘Sri Lanka Ranjana’ for my then 25 years’ service to Sri Lanka in Australia. I feel very privileged to be honored by my motherland, which I feel is the highest accolade one can ever get.”

There were many more accolades over the years:

15.10. 2004, Serendib News, 2004 Business and Community Award.

4.2.2008, Award for Services to the SL Community by The Consulate of Sri Lanka in Victoria (by R. Arambewela)

2024 – SL Consul General’s Award

In 2025 , Victor was one of the ten outstanding Sri Lankans in Australia at the Lankan Fest.

An annual Victor Melder Appreciation award was established to honour an outstanding member by the SriLankan Consulate.

The following appreciation by the late Gamini Dissanayake is very appropriate.

Comment by the late Minister Gamini Dissanayake, in the comment book of the VMSL library.

A man is attached to many things. Attachments though leading to sorrow in the end

are the living reality of life. Amongst these many attachments, the most noble are the attachments to one’s family and to one’s country. You have left Sri Lanka long ago but “she” is within you yet and every nerve and sinew of your body, mind and soul seem to belong there. In your love for the country of your birth you seem to have no racial or religious connotations – you simply love “HER” – the pure, clear, simple, abstract and glowing Sri Lanka of our imagination and vision. You are an example of what all Sri Lankan’s should be. May you live long with your vision and may Sri Lanka evolve to deserve sons like you.

With my best Wishes.

Gamini Dissanayake, Minister from Sri Lanka.

15 February 1987.

The Victor Melder Lecture

The Monash council established the Victor Melder Lecture which is presented every February. It is now an annual event looked forward to by Melbournians. A guest lecturer is carefully chosen each year for this special event.

Victor and his library has featured on many publications such as the Sunday Times in 2008 and LMD International in 2026.

“Although having been a railway man, I am a poor traveler and get travel sickness, hence I have not travelled much. I have never been back to Sri Lanka, never travelled in Australia, not even to Geelong. I am happiest doing what I like best, either at Church or in this library. My younger daughter has finally given up after months of trying to coax, cajole and coerce me into a trip to Sri Lanka to celebrate this (90th) birthday.

I am most fortunate that over the years I have made good friends, some from my school days. It is also a great privilege to grow old in the company of friends — like-minded individuals who have spent their childhood and youth in the same environment as oneself and shared similar life experiences.”

Victor’s love of books started from childhood. Since his young years he has been interested in reading. At St Mary’s College, Nawalapitiya, the library had over 300 books on Greek and Roman history and mythology and he read every one of them.

He read the newspapers daily, which his parents subscribed to, including the ‘Readers Digest’.His mother was an avid fan of Crossword Puzzles and encouraged all the children to follow her, a trait which he continues to this day.

At his workplace in Melbourne, Victor encountered many who asked questions about Ceylon. Often, he could not find an answer to these queries. This was long before the internet existed. He then started getting books on Ceylon/SriLanka and reading them. Very soon his collection expanded and he thought of the Vicor Melder SriLanka Library as source of reference. It is now a vast collection of over 7,000 books, magazines and periodicals.

Another driver of his service to fellow men is his deep Catholic faith in which he follows the footsteps of the Master.

Victor was baptized at St Anthony’s Cathedral, Kandy by Fr Galassi, OSB. Since the age of 10 he have been involved with Church activities both in Sri Lanka and Australia. He remains a devout Catholic and this underlies his spirit of service to fellowmen.

He began as an Altar Server at St Mary’s Church, Nawalapitiya, and continued even in his adult life. In Australia, Esther and Victor have been Parishioners at St Dominic’s Church, Broadmeadows, since 1970.He started as an Adult Server and have been an Altar Server Trainer, Reader and Special Minister He was a member of the ‘Counting Team’ for monies collected at Sunday Masses, for 35 years.

He has actively retired from this work since 2010, but is still ‘on call’, to help when required. To add in his own words

“My Catholic faith has always been important to me, and I can never imagine my having spent a day away from God. Faith is all that matters to Esther too. We attend daily Mass and busy ourselves with many activities in our Parish Church.

For nearly 25 years, we have also been members of a religious order ‘The Community of the Sons & Daughters of God’, it is contemplative and monastic in nature, we are veritable monks in the world. We do no good works, other than show Christ to the world, by our actions. Both Esther and I, after much prayer and discernment have become more deeply involved, taking vows of poverty, obedience and chastity, within the Community. Our spirituality gives us much peace, solace and comfort.”

“This is not my CV for beatification and canonization. My faith is in fact an antidote for overcoming evil, I too struggle like everyone else. I have to exorcise the demons within me by myself. I am a perfect candidate for “being a street angel and home devil” by my constant impatience, lack of tolerance and wanting instant perfection from everyone. “

The above exemplifies the humility of the man who admits to his foibles.

More than 25 years ago The Ceylon Society of Australia was formed in Sydney by a group of Ceylon lovers led by Hugh Karunanayake. Very soon the Melbourne chapter of the organization was formed, and Victor was a crucial part of this. At every Talk, Victor displayed books relevant to the topic. For many years he continued to do so carrying a big box of books and driving a fair distance to the meeting place. Eventually when he could no longer drive his car, he made certain that the books reached the venue through his close friend, Hemal Gurusinghe.

He also was the guest speaker at one of the meetings and he regaled the audience with railway stories.

Victor has dedicated his life on this mission, and we can be proud of his achievements. His vision is to find a permanent home for his library where future generations can use it and continue the service that he commenced. The plea is to get like-minded individuals in the quest to find a suitable and permanent home for the Victor Melder Srilankan Library.

by Dr. Srilal Fernando

Features

Sri Lanka to Host First-Ever World Congress on Snakes in Landmark Scientific Milestone

Sri Lanka is set to make scientific history by hosting the world’s first global conference dedicated entirely to snake research, conservation and public health, with the World Congress on Snakes (WCS) 2026 scheduled to take place from October 1–4 at The Grand Kandyan Hotel in Kandy World Congress on Snakes.

The congress marks a major milestone not only for Sri Lanka’s biodiversity research community but also for global collaboration in herpetology, conservation science and snakebite management.

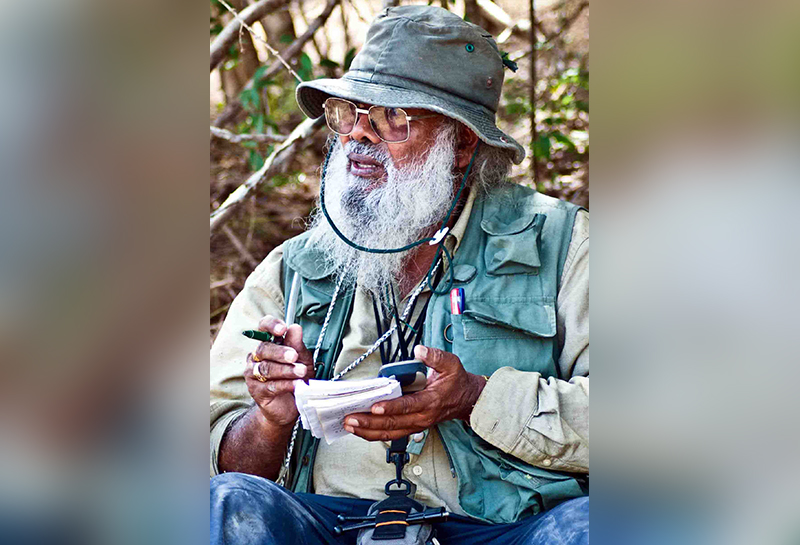

Congress Chairperson Dr. Anslem de Silva described the event as “a long-overdue global scientific platform that recognises the ecological, medical and cultural importance of snakes.”

“This will be the first international congress fully devoted to snakes — from their evolution and taxonomy to venom research and snakebite epidemiology,” Dr. de Silva said. “Sri Lanka, with its exceptional biodiversity and deep ecological relationship with snakes, is a fitting host for such a historic gathering.”

Global Scientific Collaboration

The congress has been established through an international scientific partnership, bringing together leading experts from Sri Lanka, India and Australia. It is expected to attract herpetologists, wildlife conservationists, toxinologists, veterinarians, genomic researchers, policymakers and environmental organisations from around the world.

The International Scientific Committee includes globally respected experts such as Prof. Aaron Bauer, Prof. Rick Shine, Prof. Indraneil Das and several other authorities in reptile research and conservation biology.

Dr. de Silva emphasised that the congress is designed to bridge biodiversity science, medicine and society.

“Our aim is not merely to present academic findings. We want to translate science into practical conservation action, improved public health strategies and informed policy decisions,” he explained.

Addressing a Neglected Public Health Crisis

A key pillar of the congress will be snakebite envenoming — widely recognised as a neglected tropical health problem affecting rural communities across Asia, Africa and Latin America.

“Snakebite is not just a medical issue; it is a socio-economic issue that disproportionately impacts farming communities,” Dr. de Silva noted. “By bringing clinicians, toxinologists and conservation scientists together, we can strengthen prevention strategies, improve treatment protocols and promote community education.”

Scientific sessions will explore venom biochemistry, clinical toxinology, antivenom sustainability and advances in genomic research, alongside broader themes such as ecological behaviour, species classification, conservation biology and environmental governance.

Dr. de Silva stressed that fear-driven persecution of snakes, habitat destruction and illegal wildlife trade continue to threaten snake populations globally.

“Snakes play an essential ecological role, particularly in controlling rodent populations and maintaining agricultural balance,” he said. “Conservation and public safety are not opposing goals — they are interconnected. Scientific understanding is the foundation for coexistence.”

The congress will also examine cultural perceptions of snakes, veterinary care, captive management, digital monitoring technologies and integrated conservation approaches linking biodiversity protection with human wellbeing.

Strategic Importance for Sri Lanka

Hosting the global event in the historic city of Kandy — a UNESCO World Heritage site — is expected to significantly enhance Sri Lanka’s standing as a hub for scientific and environmental collaboration.

Dr. de Silva pointed out that the benefits extend beyond the four-day meeting.

“This congress will open doors for Sri Lankan researchers and students to access world-class expertise, training and international partnerships,” he said. “It will strengthen our national research capacity in biodiversity and environmental health.”

He added that the event would also generate economic activity and position Sri Lanka as a destination for high-level scientific conferences, expanding the country’s international image beyond traditional tourism promotion.

The congress has received support from major international conservation bodies including the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Save the Snakes, Cleveland Metroparks Zoo and the Amphibian and Reptile Research Organization of Sri Lanka (ARROS).

As preparations gather momentum, Dr. de Silva expressed optimism that the World Congress on Snakes 2026 would leave a lasting legacy.

“This is more than a conference,” he said. “It is the beginning of a global movement to promote science-based conservation, improve snakebite management and inspire the next generation of researchers. Sri Lanka is proud to lead that conversation.”

By Ifham Nizam

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoBathiya & Santhush make a strategic bet on Colombo

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoSeeing is believing – the silent scale behind SriLankan’s ground operation

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoProtection of Occupants Bill: Good, Bad and Ugly

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPrime Minister Attends the 40th Anniversary of the Sri Lanka Nippon Educational and Cultural Centre

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoCoal ash surge at N’cholai power plant raises fresh environmental concerns

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoHuawei unveils Top 10 Smart PV & ESS Trends for 2026

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?