Features

Events leading to the schools takeover by the Sirimavo government

(Excerpted from Memoirs of a Cabinet Secretary by BP Peiris)

In many of her public speeches, the Prime Minister used to emphasize the fact that she was following the policies of her late husband. S.W.R.D., in his first Queen’s Speech, had said “My Government wishes to assure minorities, religious, racial and otherwise, that they need have no fear of injustice or discrimination in the carrying out of its policies and pogrammes”. And now, following those policies, Madam’s Government introduced the Objects and Places of Worship Bill.

This was a Bill to control the indiscriminate establishment of places of worship. It purported to restrict the establishment of places of worship in order to ensure the peaceful pursuit of their faith by the people of the country.

A place of worship could not be established unless there were at least 250 adherents of that particular faith within a radius of half a mile of the proposed location of such place of worship. A licence from the Minister was a prerequisite for such erection, and a power to the Minister to grant a licence implied, in law, a power to refuse such licence.

The proposed law would have prevented me from putting up a tent in my garden for the purposes of meditation and prayer but, as a Buddhist, I would have had no difficulty in obtaining the requisite number of signatures. Persons of other faiths might have experienced some difficulty. On reading the Bill before issuing it to the Ministers, it struck me that the Bill was void under our Constitution.

Section 29 gave Parliament the widest legislative powers in the fewest words “to make laws for the peace, order and good government of the Island”, but went on to enact “No such law shall prohibit or restrict the free exercise of any religion”.

I had, as Secretary, no power to stop the circulation of the Bill as a Cabinet paper but I felt uneasy about the Government introducing in Parliament a Bill which I knew would be contested in the courts, particularly by the Roman Catholic community, as soon as it received the Royal Assent. I asked Attorney-General Jansze on the telephone of his opinion and he said the Bill was void. I telephoned the Legal Draftsman, Percy de Silva and inquired how he came to draft a void Bill. “Under strong protest,” he said “I told them the bloody thing was void.”

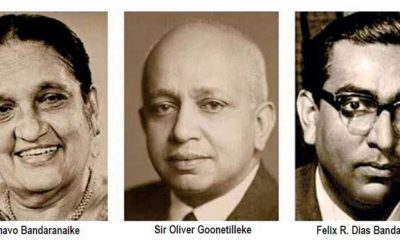

When the item came on the Agenda, I felt it to be my duty to point out to the Ministers that they were going to present in Parliament a Bill which was void under the Constitution. As Secretary to the Cabinet, I have never considered myself to be a mere quill-driver. There was no point in raising with the Prime Minister a legal matter because she understood no law. I therefore addressed Felix Dias. I told him that I had spoken to the Attorney-General and the Draftsman and that they were both agreed with me that the Bill was void.

I received a sharp return from Felix “Mr Peiris, we are not bothered about the legality of things”. I gave no further advice on the matter. The Bill was presented in Parliament but lapsed on prorogation. It was presented again during the next Session and lapsed for the second time (1962). Strong protests against the Bill were made by the Roman Catholics but these went unheeded. The Bill was introduced because some Roman Catholics had, overnight, erected in some village a prefabricated chapel within half a mile of a Buddhist temple.

From temples and churches, hymns and chants, the Cabinet got down to reconsider the National Anthem. Wise old pundits had said that all the country’s ills were due to he fact that the anthem was wrong according to ‘gana’, a term in oriental music which I do not understand. Apparently it refers to meter.

The pundit, a long haired old boy in national dress whose head of hair reminded me of Einstein, Bertrand Russell and our own Professor Karunaratne of revered memory, pointed out that our anthem began on a descending scale, that is, from middle C down to B, then to A and to G, whereas they should be ascending notes as in “God Save the King”, or the Marseillaise.

Madam Prime Minister minister told me, that there might be something in the suggestion as no Government since 1947 had gone its full term. It was agreed that leading scholars and musicians should be consulted regarding the alteration of the anthem without radically altering its sentiment or music. There are difficulties about tinkering with National Anthems and National Flags. Gramophone records of the Anthem had been made, the melody had been set to music and distributed to foreign bands to be played on ceremonial occasions in their countries.

Only one sensible suggestion was made, and that by the long-haired pundit, namely, drop the first eight bars and carry on with the rest without alteration. I thought this was an eminently suitable suggestion but, at that time, it was not accepted.

There were, to my mind, three classes of persons who were generally non grata, and distasteful to the Government. The first was the Tamils, the second the Roman Catholics and the third was sui generic – Hema Henry Basnayake, Chief Justice.

The Tamils were giving the Government a great deal of trouble by not cooperating in our language policy. Every Tamil was expected loyally to submit to the Sinhala Only policy and those who showed some love and loyalty to their own ancient language had naturally no love or loyalty towards the Government.

The Roman Catholics appeared to set the Government a problem for reasons unknown to me. There were numbers of monks and nuns in the island. There were also some Burmese and German Buddhist priests, all respected men and women who had been resident here for long years on temporary residence permits There were Roman Catholic priests and nuns who had been resident here so long that ‘they did not require any permits, but their numbers were few.

The Government wished to be rid of the Roman Catholic priests and nuns but there were practical difficulties about getting every foreign priest and nun out of the Island. It was well known that our people were not willing to work in the Leprosy Hospitals where the Catholic nuns gave devoted service to the patients.

Even in the general hospitals some of the patients who could afford to pay preferred to enter the non-paying wards, which were in charge of the nuns, because they received infinitely better treatment there. Their kindness and readiness to come to the service and assistance of a patient were well known and deeply appreciated by all but that appreciation was never acclaimed by politicians and public officials in public.

In the end, the Government succeeded in getting them out; but what exactly did the country gain? As late as 1967, His Lordship the Bishop of Colombo, the Rt Rev. Harold de Soysa, after a visit to the Hendala Leprosy Hospital, wrote in the Ceylon Churchman: “It was indeed a cause for much praise to God that although our previous Government callously deprived those suffering patients of the loving ministrations of the nursing nuns who cared for them and ministered to them, on this day of their treat, there were at least twenty Roman Catholic nuns who had come from a nearby convent to be with them and three or four priests as well as our own clergy from the Cathedral parish who minister to the Anglicans there and take regular service in the Chapel.”

Except in very special cases, no visa was to be extended when the person to whom the visa had been granted could be replaced by a Ceylonese, and where any such decision is taken to extend any such visa, it should be submitted for the approval of the Prime Minister. There were 210 non-Ceylonese Roman Catholic priests of whom 178 were on visas, and 997 with 556 on visas. These visas were not to be approved without the approval of the Prime Minister.

It was also decided that a member of the priesthood of any religious denomination should not be employed in the public service in any post which could be filled by a layman. This was aimed principally at the priests teaching in the Roman Catholic schools but had to be so worded as not to make the point obvious. In the result, Buddhist priests teaching in the pirivenas and other educational institutions were also caught up, and there was a howl in the country from the Buddhist public. What compromise there must have been because it was only the Catholics that went out.

There was also the other side of the medal. One day, a clerk from the Ministry of External Affairs, of which Mr N. Q. Dias was Permanent Secretary, walked into my room and said that Mr Dias had suggested that I should take steps to form a Buddhist Association in the Cabinet Office. I was not under N. Q. in any way and I asked the clerk to tell Mr Dias that, so long as I was in the Cabinet Office, there were two things I would not tolerate – politics and religion – the first was barred by rules, while the second was entirely a matter between a man and his Maker.

I have dealt with the Tamils and the Roman Catholics. I come to the third class I mentioned – Chief Justice Basnayake standing by himself. He was an upstanding man of sturdy independence and integrity. On the Bench, he was only concerned with the legal argument placed before him. The fact that counsel for the appellant was a senior silk and counsel for the respondent was a raw junior did not weigh with the Chief. He listened to both with equal attention and respect.

This attitude was resented by some of the seniors who expected a little deferential treatment at the hand of the Chief who was not concerned with the personalities at the Bar. Basnayake was, therefore, among the higher-ups of the legal circle, not a very popular judge. In fact, he was an ideal and independent judge who did not care whether he was popular or not. His unpopularity, if any, went beyond the members of the Bar; it extended to the members of the Government.

It was well known that Sirimavo and her Ministers did not like him because he was too independent and not of ‘our way of thinking’. What was ‘our way of thinking?’ Every public servant, every head of department, was expected to ‘toe the line’ and anyone who did not do so was not of ‘our way of thinking’. When the coup trial, to which reference will be made later, was impending, the law was specially amended to divest the Chief Justice of his statutory power of nominating the Bench to sit at Bar and that power was vested in the Minister of Justice.

Features

Rebuilding the country requires consultation

A positive feature of the government that is emerging is its responsiveness to public opinion. The manner in which it has been responding to the furore over the Grade 6 English Reader, in which a weblink to a gay dating site was inserted, has been constructive. Government leaders have taken pains to explain the mishap and reassure everyone concerned that it was not meant to be there and would be removed. They have been meeting religious prelates, educationists and community leaders. In a context where public trust in institutions has been badly eroded over many years, such responsiveness matters. It signals that the government sees itself as accountable to society, including to parents, teachers, and those concerned about the values transmitted through the school system.

This incident also appears to have strengthened unity within the government. The attempt by some opposition politicians and gender misogynists to pin responsibility for this lapse on Prime Minister Dr Harini Amarasuriya, who is also the Minister of Education, has prompted other senior members of the government to come to her defence. This is contrary to speculation that the powerful JVP component of the government is unhappy with the prime minister. More importantly, it demonstrates an understanding within the government that individual ministers should not be scapegoated for systemic shortcomings. Effective governance depends on collective responsibility and solidarity within the leadership, especially during moments of public controversy.

The continuing important role of the prime minister in the government is evident in her meetings with international dignitaries and also in addressing the general public. Last week she chaired the inaugural meeting of the Presidential Task Force to Rebuild Sri Lanka in the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah. The composition of the task force once again reflects the responsiveness of the government to public opinion. Unlike previous mechanisms set up by governments, which were either all male or without ethnic minority representation, this one includes both, and also includes civil society representation. Decision-making bodies in which there is diversity are more likely to command public legitimacy.

Task Force

The Presidential Task Force to Rebuild Sri Lanka overlooks eight committees to manage different aspects of the recovery, each headed by a sector minister. These committees will focus on Needs Assessment, Restoration of Public Infrastructure, Housing, Local Economies and Livelihoods, Social Infrastructure, Finance and Funding, Data and Information Systems, and Public Communication. This structure appears comprehensive and well designed. However, experience from post-disaster reconstruction in countries such as Indonesia and Sri Lanka after the 2004 tsunami suggests that institutional design alone does not guarantee success. What matters equally is how far these committees engage with those on the ground and remain open to feedback that may complicate, slow down, or even challenge initial plans.

An option that the task force might wish to consider is to develop a linkage with civil society groups with expertise in the areas that the task force is expected to work. The CSO Collective for Emergency Relief has set up several committees that could be linked to the committees supervised by the task force. Such linkages would not weaken the government’s authority but strengthen it by grounding policy in lived realities. Recent findings emphasise the idea of “co-production”, where state and society jointly shape solutions in which sustainable outcomes often emerge when communities are treated not as passive beneficiaries but as partners in problem-solving.

Cyclone Ditwah destroyed more than physical infrastructure. It also destroyed communities. Some were swallowed by landslides and floods, while many others will need to be moved from their homes as they live in areas vulnerable to future disasters. The trauma of displacement is not merely material but social and psychological. Moving communities to new locations requires careful planning. It is not simply a matter of providing people with houses. They need to be relocated to locations and in a manner that permits communities to live together and to have livelihoods. This will require consultation with those who are displaced. Post-disaster evaluations have acknowledged that relocation schemes imposed without community consent often fail, leading to abandonment of new settlements or the emergence of new forms of marginalisation. Even today, abandoned tsunami housing is to be seen in various places that were affected by the 2004 tsunami.

Malaiyaha Tamils

The large-scale reconstruction that needs to take place in parts of the country most severely affected by Cyclone Ditwah also brings an opportunity to deal with the special problems of the Malaiyaha Tamil population. These are people of recent Indian origin who were unjustly treated at the time of Independence and denied rights of citizenship such as land ownership and the vote. This has been a festering problem and a blot on the conscience of the country. The need to resettle people living in those parts of the hill country which are vulnerable to landslides is an opportunity to do justice by the Malaiyaha Tamil community. Technocratic solutions such as high-rise apartments or English-style townhouses that have or are being contemplated may be cost-effective, but may also be culturally inappropriate and socially disruptive. The task is not simply to build houses but to rebuild communities.

The resettlement of people who have lost their homes and communities requires consultation with them. In the same manner, the education reform programme, of which the textbook controversy is only a small part, too needs to be discussed with concerned stakeholders including school teachers and university faculty. Opening up for discussion does not mean giving up one’s own position or values. Rather, it means recognising that better solutions emerge when different perspectives are heard and negotiated. Consultation takes time and can be frustrating, particularly in contexts of crisis where pressure for quick results is intense. However, solutions developed with stakeholder participation are more resilient and less costly in the long run.

Rebuilding after Cyclone Ditwah, addressing historical injustices faced by the Malaiyaha Tamil community, advancing education reform, changing the electoral system to hold provincial elections without further delay and other challenges facing the government, including national reconciliation, all require dialogue across differences and patience with disagreement. Opening up for discussion is not to give up on one’s own position or values, but to listen, to learn, and to arrive at solutions that have wider acceptance. Consultation needs to be treated as an investment in sustainability and legitimacy and not as an obstacle to rapid decisionmaking. Addressing the problems together, especially engagement with affected parties and those who work with them, offers the best chance of rebuilding not only physical infrastructure but also trust between the government and people in the year ahead.

by Jehan Perera

Features

PSTA: Terrorism without terror continues

When the government appointed a committee, led by Rienzie Arsekularatne, Senior President’s Counsel, to draft a new law to replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), as promised by the ruling NPP, the writer, in an article published in this journal in July 2025, expressed optimism that, given Arsekularatne’s experience in criminal justice, he would be able to address issues from the perspectives of the State, criminal justice, human rights, suspects, accused, activists, and victims. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), produced by the Committee, has been sharply criticised by individuals and organisations who expected a better outcome that aligns with modern criminal justice and human rights principles.

When the government appointed a committee, led by Rienzie Arsekularatne, Senior President’s Counsel, to draft a new law to replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), as promised by the ruling NPP, the writer, in an article published in this journal in July 2025, expressed optimism that, given Arsekularatne’s experience in criminal justice, he would be able to address issues from the perspectives of the State, criminal justice, human rights, suspects, accused, activists, and victims. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), produced by the Committee, has been sharply criticised by individuals and organisations who expected a better outcome that aligns with modern criminal justice and human rights principles.

This article is limited to a discussion of the definition of terrorism. As the writer explained previously, the dangers of an overly broad definition go beyond conviction and increased punishment. Special laws on terrorism allow deviations from standard laws in areas such as preventive detention, arrest, administrative detention, restrictions on judicial decisions regarding bail, lengthy pre-trial detention, the use of confessions, superadded punishments, such as confiscation of property and cancellation of professional licences, banning organisations, and restrictions on publications, among others. The misuse of such laws is not uncommon. Drastic legislation, such as the PTA and emergency regulations, although intended to be used to curb intense violence and deal with emergencies, has been exploited to suppress political opposition.

International Standards

The writer’s basic premise is that, for an act to come within the definition of terrorism, it must either involve “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” or be committed to achieve an objective of an individual or organisation that uses “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” to realise its aims. The UN General Assembly has accepted that the threshold for a possible general offence of terrorism is the provocation of “a state of terror” (Resolution 60/43). The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe has taken a similar view, using the phrase “to create a climate of terror.”

In his 2023 report on the implementation of the UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, the Secretary-General warned that vague and overly broad definitions of terrorism in domestic law, often lacking adequate safeguards, violate the principle of legality under international human rights law. He noted that such laws lead to heavy-handed, ineffective, and counterproductive counter-terrorism practices and are frequently misused to target civil society actors and human rights defenders by labelling them as terrorists to obstruct their work.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has stressed in its Handbook on Criminal Justice Responses to Terrorism that definitions of terrorist acts must use precise and unambiguous language, narrowly define punishable conduct and clearly distinguish it from non-punishable behaviour or offences subject to other penalties. The handbook was developed over several months by a team of international experts, including the writer, and was finalised at a workshop in Vienna.

Anti-Terrorism Bill, 2023

A five-member Bench of the Supreme Court that examined the Anti-Terrorism Bill, 2023, agreed with the petitioners that the definition of terrorism in the Bill was too broad and infringed Article 12(1) of the Constitution, and recommended that an exemption (“carve out”) similar to that used in New Zealand under which “the fact that a person engages in any protest, advocacy, or dissent, or engages in any strike, lockout, or other industrial action, is not, by itself, a sufficient basis for inferring that the person” committed the wrongful acts that would otherwise constitute terrorism.

While recognising the Court’s finding that the definition was too broad, the writer argued, in his previous article, that the political, administrative, and law enforcement cultures of the country concerned are crucial factors to consider. Countries such as New Zealand are well ahead of developing nations, where the risk of misuse is higher, and, therefore, definitions should be narrower, with broader and more precise exemptions. How such a “carve out” would play out in practice is uncertain.

In the Supreme Court, it was submitted that for an act to constitute an offence, under a special law on terrorism, there must be terror unleashed in the commission of the act, or it must be carried out in pursuance of the object of an organisation that uses terror to achieve its objectives. In general, only acts that aim at creating “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” should come under the definition of terrorism. There can be terrorism-related acts without violence, for example, when a member of an extremist organisation remotely sabotages an electronic, automated or computerised system in pursuance of the organisation’s goal. But when the same act is committed by, say, a whizz-kid without such a connection, that would be illegal and should be punished, but not under a special law on terrorism. In its determination of the Bill, the Court did not address this submission.

PSTA Proposal

Proposed section 3(1) of the PSTA reads:

Any person who, intentionally or knowingly, commits any act which causes a consequence specified in subsection (2), for the purpose of-

(a) provoking a state of terror;

(b) intimidating the public or any section of the public;

(c) compelling the Government of Sri Lanka, or any other Government, or an international organisation, to do or to abstain from doing any act; or

(d) propagating war, or violating territorial integrity or infringing the sovereignty of Sri Lanka or any other sovereign country, commits the offence of terrorism.

The consequences listed in sub-section (2) include: death; hurt; hostage-taking; abduction or kidnapping; serious damage to any place of public use, any public property, any public or private transportation system or any infrastructure facility or environment; robbery, extortion or theft of public or private property; serious risk to the health and safety of the public or a section of the public; serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with, any electronic or automated or computerised system or network or cyber environment of domains assigned to, or websites registered with such domains assigned to Sri Lanka; destruction of, or serious damage to, religious or cultural property; serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with any electronic, analogue, digital or other wire-linked or wireless transmission system, including signal transmission and any other frequency-based transmission system; without lawful authority, importing, exporting, manufacturing, collecting, obtaining, supplying, trafficking, possessing or using firearms, offensive weapons, ammunition, explosives, articles or things used in the manufacture of explosives or combustible or corrosive substances and biological, chemical, electric, electronic or nuclear weapons, other nuclear explosive devices, nuclear material, radioactive substances, or radiation-emitting devices.

Under section 3(5), “any person who commits an act which constitutes an offence under the nine international treaties on terrorism, ratified by Sri Lanka, also commits the offence of terrorism.” No one would contest that.

The New Zealand “carve-out” is found in sub-section (4): “The fact that a person engages in any protest, advocacy or dissent or engages in any strike, lockout or other industrial action, is not by itself a sufficient basis for inferring that such person (a) commits or attempts, abets, conspires, or prepares to commit the act with the intention or knowledge specified in subsection (1); or (b) is intending to cause or knowingly causes an outcome specified in subsection (2).”

While the Arsekularatne Committee has proposed, including the New Zealand “carve out”, it has ignored a crucial qualification in section 5(2) of that country’s Terrorism Suppression Act, that for an act to be considered a terrorist act, it must be carried out for one or more purposes that are or include advancing “an ideological, political, or religious cause”, with the intention of either intimidating a population or coercing or forcing a government or an international organisation to do or abstain from doing any act.

When the Committee was appointed, the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka opined that any new offence with respect to “terrorism” should contain a specific and narrow definition of terrorism, such as the following: “Any person who by the use of force or violence unlawfully targets the civilian population or a segment of the civilian population with the intent to spread fear among such population or segment thereof in furtherance of a political, ideological, or religious cause commits the offence of terrorism”.

The writer submits that, rather than bringing in the requirement of “a political, ideological, or religious cause”, it would be prudent to qualify proposed section 3(1) by the requirement that only acts that aim at creating “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” or are carried out to achieve a goal of an individual or organisation that employs “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” to attain its objectives should come under the definition of terrorism. Such a threshold is recognised internationally; no “carve out” is then needed, and the concerns of the Human Rights Commission would also be addressed.

by Dr. Jayampathy Wickramaratne

President’s Counsel

Features

ROCK meets REGGAE 2026

We generally have in our midst the famous JAYASRI twins, Rohitha and Rohan, who are based in Austria but make it a point to entertain their fans in Sri Lanka on a regular basis.

We generally have in our midst the famous JAYASRI twins, Rohitha and Rohan, who are based in Austria but make it a point to entertain their fans in Sri Lanka on a regular basis.

Well, rock and reggae fans get ready for a major happening on 28th February (Oops, a special day where I’m concerned!) as the much-awaited ROCK meets REGGAE event booms into action at the Nelum Pokuna outdoor theatre.

It was seven years ago, in 2019, that the last ROCK meets REGGAE concert was held in Colombo, and then the Covid scene cropped up.

Chitral Somapala with BLACK MAJESTY

This year’s event will feature our rock star Chitral Somapala with the Australian Rock+Metal band BLACK MAJESTY, and the reggae twins Rohitha and Rohan Jayalath with the original JAYASRI – the full band, with seven members from Vienna, Austria.

According to Rohitha, the JAYASRI outfit is enthusiastically looking forward to entertaining music lovers here with their brand of music.

Their playlist for 28th February will consist of the songs they do at festivals in Europe, as well as originals, and also English and Sinhala hits, and selected covers.

Says Rohitha: “We have put up a great team, here in Sri Lanka, to give this event an international setting and maintain high standards, and this will be a great experience for our Sri Lankan music lovers … not only for Rock and Reggae fans. Yes, there will be some opening acts, and many surprises, as well.”

Rohitha, Chitral and Rohan: Big scene at ROCK meets REGGAE

Rohitha and Rohan also conveyed their love and festive blessings to everyone in Sri Lanka, stating “This Christmas was different as our country faced a catastrophic situation and, indeed, it’s a great time to help and share the real love of Jesus Christ by helping the poor, the needy and the homeless people. Let’s RISE UP as a great nation in 2026.”

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoNational Communication Programme for Child Health Promotion (SBCC) has been launched. – PM

-

News2 days ago

News2 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II