Features

Educational reforms Sri Lanka demands today for a brighter tomorrow

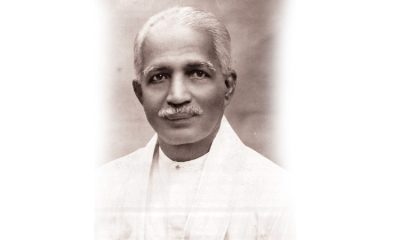

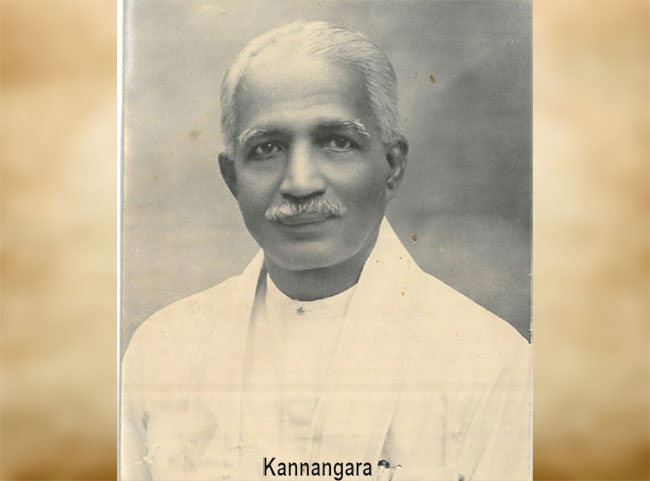

As a Sri Lankan who benefitted from free education, I feel honoured and privileged to deliver this Dr. C.W.W. Kannangara Memorial Oration, the 32nd in the lecture series inaugurated in 1988 on the twentieth anniversary of his demise.

I am well aware of the gravity of this task, particularly when considering the impressive stature of previous orators, often beneficiaries of free education themselves. The current economic, political and social crisis adds a further layer of complexity to the context in which this oration is delivered today. Within that backdrop, and with a keen awareness of the responsibility placed on my shoulders, I shall humbly endeavour to do justice to this task.

I am a medical practitioner by profession; however, I have spent most of my life sharing knowledge with friends, colleagues and students, as a teacher. This student-teacher reincarnation has been the focus and foundation of my entire life. Taking on the task of teaching arithmetic to my elder sister at the age of fifteen was my first venture into teaching. While waiting for entrance to the Medical Faculty, during the five years of university and well after that, I spent a considerable proportion of my time as a teacher. I had supported a number of students to pass their examinations for free, and as word spread of my skill in getting students through examinations, so many requests came in that I ended up establishing and running a private education institute named ‘Vidya Nadi’. This was more because I could not avoid the responsibility than for economic reasons. Most of those students are very prominent members of society today. The life lessons I obtained from being a teacher were significant and serve me to this day. Since then, I spent most of my life teaching and carrying out research in local and foreign universities, so much so that I would like to note that I have spent more time as a teacher and a researcher than as a doctor.

Within the same time frame, as a socially sensitive and politically informed person, as well as a medical student, I was also an activist who fought to defend free education, which gave me a different perspective on education. The complex and challenging context of today forces me to revisit this past and to re-examine the path we took in our younger days.

Against this complex background, my approach to this lecture today is based on two contrasting viewpoints Sri Lankan society holds on free education and the Kannangara legacy. Professor Narada Warnasuriya, who is a dear and well-respected teacher to me, during his Kannangara Memorial Lecture delivered in 2008, explained these two viewpoints as follows:

One group sees the Kannangara legacy in a single dimension, as a valuable basis for further expanding access to education, which also helps preserve fairness and social justice. They see it as a keystone of a just and conflict-free sustainable society.

The second group acknowledges that the Kannangara reforms had a major impact on bringing about a positive societal, and social transformation, but considers such changes irrelevant in the present context of a globalized free market economy. Professor Warnasuriya states that this group sees the Kannangara reforms as ‘a sacred cow, an archaic barrier to development, which stands in the way of building a successful knowledge-based economy’.

As an individual examining the status of education with an analytical mind, I do not wish to align myself with either of these groups exclusively, and decided to deliver this lecture from a neutral position, considering the positive and negative aspects of both viewpoints. This oration is therefore entitled Educational reforms Sri Lanka demands today for a brighter tomorrow and I plan to expand the discussion on Kannangara Legacy

I should also like to clarify that I prefer to refer to this as ‘our lecture’ rather than ‘my lecture’, because this lecture necessarily contains the views of a large group of like-minded people who work together with me as a team, on educational reforms.

Most of the facts forming the basis of this lecture are extracted from the recently published thirty-ninth (one-hundred page) special issue of the trilingual journal ‘Gaveshana’, entitled: ‘Educational reforms the country demands to create a productive citizen adaptable to the modern world’. This edition of Gaveshana is particularly significant in that it was published in the form of a research publication based on original data, and secondly, since a cross-section of educationists and officials from the Education sector who are directly involved with Sri Lankan educational reforms contributed to this publication, as did external experts who brought in a broader, societal viewpoint.

As someone who strongly believes that ‘a person alone cannot win a battle against the deep seas’, I would like to note that we are in an era in which not one but thousands of Dr. C.W.W. Kannanagaras are needed. Furthermore, it is important to note that educational reforms should not take a top-down approach but aim to incorporate the requirements and viewpoints of the beneficiaries of such reforms as honoured stakeholders: the knowledgeable student community, teachers and the general public. Such reforms should be informed by a regular feed-back loop, follow-up and grass-roots research. Educational reforms must be a dynamic process, not a static one, and follow-up research should be used to change not only the direction, but also the content of the reforms, if and when necessary.

This is the responsibility history vests on our shoulders, and in order to do justice to this obligation, I am deeply grateful to the Director General of the National Institute of Education and the staff of its Research and Planning Department for giving me this opportunity.

I was influenced early in life to believe the Stalinist concept of It is not heroes that make history, but history that makes heroes. But today, I am of the firm opinion that there are individuals who make constructive (or destructive) contributions to history. Dr. C.W.W. Kannangara is undoubtedly such a person who has left a lasting and positive contribution a hero that did change history, and it is therefore necessary to study not only the history he bequeathed but the person himself.

Who is Dr C.W.W Kannangara?

Dr. Christopher William Wijekoon Kannangara was born on October 13, 1884, at Randombe village, Ambalangoda. The third child in his family, he lost his mother early in life when his mother died giving birth to a younger brother. His father had five children from his first marriage and four from his second marriage. Although he was well looked after by his stepmother, he had faced the sad fate of losing his mother early in life. His father was a Buddhist, but his mother was a devotee of the Church of England. Christopher William Wijekoon was therefore baptized as a Christian although he formally converted to Buddhism as an adult in 1917. It was, as many of his closest Christian friends said, an act of wisdom and not a political act. Moreover, he learned Sinhala and Pali languages ??as well as Buddhism from his locality and environment.

He was a bright student, initially at Ambalangoda Wesleyan College. At its triennial prize-giving ceremony, he received the attention of accomplished mathematics teacher and the then Headmaster of Richmond College, Galle, Father D.H. Darrell.

Father Darrell had graduated from the Cambridge University, England with a first-class degree in mathematics. It is documented that Father Darrell had said to young Kannangara you will have to bring a heavy cart to take home the prizes you have won’. Father Darrell had then asked the Principal of Wesleyan College to prepare young Kannangara for the open scholarship examination at Richmond College. It is evident that it was this meeting with Father Darrell, the Headmaster of Richmond College at the age of 14 years, that turned out to be the pivotal point of Dr. Kannangara’s life.

Young student Kannangara subsequently won this scholarship, enabling him to attend Richmond College with free tuition, room and board. My belief is that this full scholarship established the foundation for the gift of free education that he later bequeathed to the nation.

He had to face further adversity in his life when his father lost his job and his pension after thirty years of service, leading to significant financial difficulty for his family. I would like to emphasise on, particularly to the young generation of today, the importance of recognising how his life was not cushioned in comfort, but was one of achieving greatness despite hardship and difficulty.

He was a bright student who excelled not only in studies but also in sports. He passed the Cambridge Junior Examination with honours and came first in the country and in the British Empire in Arithmetic. He was the captain of the cricket team, played in the football team and was a member of the debating team. He was also the lead actor in the school’s production of The Merchant of Venice. He was not a ‘bookworm’, but also excelled in extracurricular activities. Sadly, it is necessary to note the significant difference between the life of Dr. Kannangara as a student and the lives of the majority of children today.

At the time, the only option available for studying abroad was a government scholarship. Twelve Richmondites sat this examination, but he was unable to secure a scholarship, thus losing the opportunity to study at a foreign university. He chose instead to study law at the Sri Lanka Law College. Father Darrell, his mentor, however, requested young Kannangara to stay on at the school as the mathematics teacher and senior housemaster of the student hostel. He accepted and fulfilled this responsibility until the untimely death of Father Darrell, after which he moved to Colombo and embarked on his legal education. During this period, he also worked as a part-time teacher at Prince of Wales College, Wesley College and Methodist College.

By 1910, he had qualified as a lawyer and returned to Galle to start his legal career. He focused on civil law, carried on social service activities simultaneously and entered formal politics in 1911, supporting Mr. Ponnambalam Ramanathan. He actively campaigned for Mr. Ramanathan when he successfully contested in the 1917 elections for the Legislative Assembly, and the two ended up establishing a close friendship thereafter. He was an eloquent speaker at the establishment of the Ceylon National Council in 1919, expounding on its objectives to direct the country and the people towards a life of political freedom with equal rights and independence.

The pivotal moment of his political life came about when he was elected to the Legislative Assembly in 1923, representing the Southern Province. He was then elected as the President of the Ceylon National Congress in 1930 and in 1931, he became Sri Lankas first Minister of Education, after being elected to the State Council of Ceylon from the Galle district. He was elected the first chairman of the Executive Committee for Education with an overwhelming majority. He was re-elected to the same position in 1936 and held that position for 16 years.

The extent of the struggles and sacrifices Dr. Kannangara underwent to achieve free education should also be evaluated in the context of the political environment of the time. He entered politics at the time of Sri Lanka achieving universal franchise. The State Council at the time had 46 members and seven ministerial portfolios were available for elected members, one of these was the education portfolio.

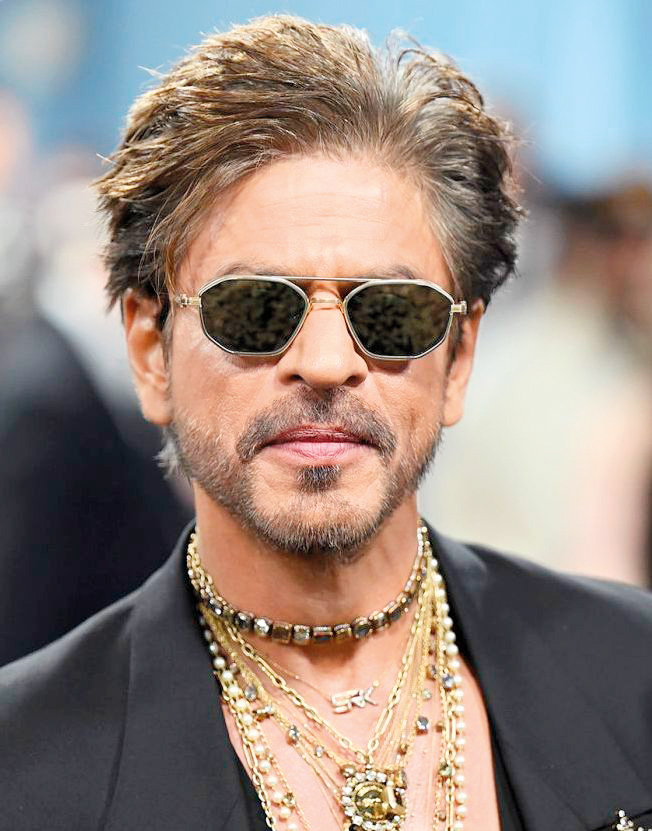

Prof Athula Sumathipala delivering the Kannangara memorial lecture

He was conferred an honorary doctorate in law at the first convocation of the University of Ceylon under the auspices of the Vice-Chancellor Sir Ivor Jennings in 1942. It was in 1945 that he managed to finally achieve the passage of parliamentary bill to establish free education in the country. And yet, Dr. Kannangara, who was venerated as the Father of Free Education, was defeated at the first national parliamentary elections held in 1947. It is time to question if this defeat was a personal one or if it was a defeat of the entire Sri Lankan nation. He lost the election to a Mr. Wilmot. A. Perera, who was backed by wealthy individuals in the United National Party and with the support of the socialist camp as well. Even the Communist Party of Sri Lanka worked against Dr. Kannangara’s election campaign.

Time does not permit an in-depth discussion of the factors leading to the election defeat of a person who achieved societal change at such a significant scale, however, I do consider this one of the greatest ironies in Sri Lankan political history.

He was re-elected as a member of parliament in 1952, and was offered the Local Government portfolio. He was however denied the education portfolio, likely due to the influence of powers that be who wished to prevent further educational reforms by Dr. Kannangara. He retired from politics in 1956 when he turned seventy-two, but served as a member of the National Education Commission, indicating his commitment towards the education of the nation, which was beyond politics.

At the time of his entry into politics, Dr. Kannangara was quite prosperous economically, having started his career as a lawyer in 1923. Twenty years of holding a ministerial role, and forty years of public service, which is indeed the basis of politics, had led to a loss of financial stability by the time he retired. He showed by example that politics should not be a money-making mechanism. The Sri Lankan government offered him a one-time stipend of Rs. Ten thousand in 1963, a substantial amount of money at the time. Considering his health needs, he was offered a monthly living allowance of Rs.500/- in 1965, and this was subsequently increased to Rs.1000/- per month.

This great son of Sri Lanka, considered the Father of Free Education, passed away on 29th September 1969 without receiving much attention from the nation.

I think it is important to highlight a factor pointed out by Senior Professor Sujeewa Amarasena when he delivered the 28th Kannangara Memorial Oration. Professor Amarasena is a proponent of the second viewpoint Professor Warnasuriya mentions, i.e., those who acknowledge that the Kannangara reforms had a major impact on bringing about a positive societal, and social transformation, but consider such changes irrelevant in the present context of a globalized free market economy.

Senior Professor Sujeewa Amarasena said, today every political party, every organization connected to education, every trade union in the government or private sector and every individual who has had some education would come forward to protect free education as a social welfare intervention. The entire country and political parties with allied student movements are in a vociferous dialogue always talking about free education without really giving the legend Dr. CWW Kannangara his due place in this dialogue. I have not seen or heard a single University or a student organization in this country commemorating Dr. CWW Kannangara on his birthday though all of them are vociferous fighters to protect free education. Hence today late Dr. CWW Kannangara is a forgotten person as stated by Mr. KHM Sumathipala in his book titled History of Education in Sri Lanka 1796 to 1965. I would like to add to that and say that not only he is a forgotten person today, but even his vision has been misinterpreted, misdirected, distorted and partly destroyed by some people who benefitted from free education.

The irony of history extends further: at a time when school education was unavailable to the entire generation of children in Sri Lanka during the Covid-19 pandemic, many teachers were committed to providing an education to children via distance / online education, as it was the only viable option, albeit flawed in some ways. Some union leaders, in the guise of so-called trade union action, worked to obstruct such teachers from providing online education. Given that all trade union leaders are beneficiaries of free education, it has to be questioned if it is not the worst mockery in the history of free education that teachers rights were considered a priority, over the right of students to obtain an education. This tragedy raises multiple questions: has the expectation that widening access to education would create selfless citizens who think beyond personal gain and fulfil their responsibilities to the nation not been realised? Did the generation who benefited from the Kannangara reforms shirk their responsibilities in the post-Kannangara era? Or is it simply that the agenda for national benefit has been rendered secondary to narrow political gains?

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result for this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

Features

Egg white scene …

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

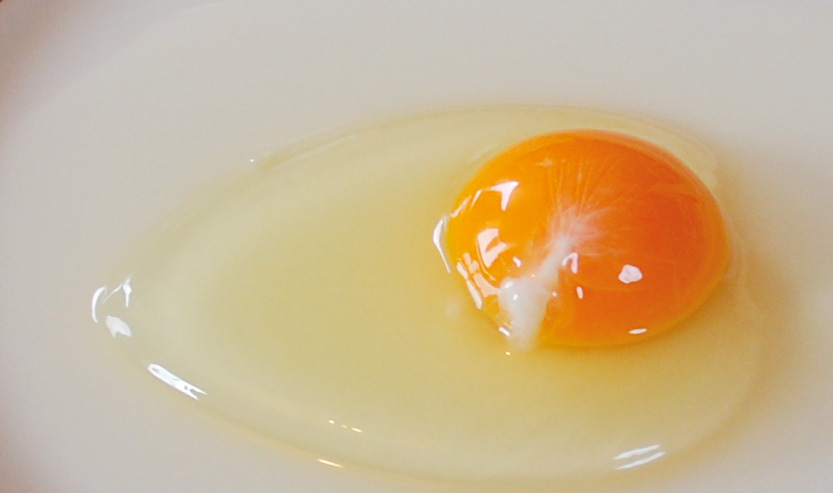

Thought of starting this week with egg white.

Yes, eggs are brimming with nutrients beneficial for your overall health and wellness, but did you know that eggs, especially the whites, are excellent for your complexion?

OK, if you have no idea about how to use egg whites for your face, read on.

Egg White, Lemon, Honey:

Separate the yolk from the egg white and add about a teaspoon of freshly squeezed lemon juice and about one and a half teaspoons of organic honey. Whisk all the ingredients together until they are mixed well.

Apply this mixture to your face and allow it to rest for about 15 minutes before cleansing your face with a gentle face wash.

Don’t forget to apply your favourite moisturiser, after using this face mask, to help seal in all the goodness.

Egg White, Avocado:

In a clean mixing bowl, start by mashing the avocado, until it turns into a soft, lump-free paste, and then add the whites of one egg, a teaspoon of yoghurt and mix everything together until it looks like a creamy paste.

Apply this mixture all over your face and neck area, and leave it on for about 20 to 30 minutes before washing it off with cold water and a gentle face wash.

Egg White, Cucumber, Yoghurt:

In a bowl, add one egg white, one teaspoon each of yoghurt, fresh cucumber juice and organic honey. Mix all the ingredients together until it forms a thick paste.

Apply this paste all over your face and neck area and leave it on for at least 20 minutes and then gently rinse off this face mask with lukewarm water and immediately follow it up with a gentle and nourishing moisturiser.

Egg White, Aloe Vera, Castor Oil:

To the egg white, add about a teaspoon each of aloe vera gel and castor oil and then mix all the ingredients together and apply it all over your face and neck area in a thin, even layer.

Leave it on for about 20 minutes and wash it off with a gentle face wash and some cold water. Follow it up with your favourite moisturiser.

Features

Confusion cropping up with Ne-Yo in the spotlight

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

At an official press conference, held at a five-star venue, in Colombo, it was indicated that the gathering marked a defining moment for Sri Lanka’s entertainment industry as international R&B powerhouse and three-time Grammy Award winner Ne-Yo prepares to take the stage in Colombo this December.

What’s more, the occasion was graced by the presence of Sunil Kumara Gamage, Minister of Sports & Youth Affairs of Sri Lanka, and Professor Ruwan Ranasinghe, Deputy Minister of Tourism, alongside distinguished dignitaries, sponsors, and members of the media.

According to reports, the concert had received the official endorsement of the Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau, recognising it as a flagship initiative in developing the country’s concert economy by attracting fans, and media, from all over South Asia.

However, I had that strange feeling that this concert would not become a reality, keeping in mind what happened to Nick Carter’s Colombo concert – cancelled at the very last moment.

Carter issued a video message announcing he had to return to the USA due to “unforeseen circumstances” and a “family emergency”.

Though “unforeseen circumstances” was the official reason provided by Carter and the local organisers, there was speculation that low ticket sales may also have been a factor in the cancellation.

Well, “Unforeseen Circumstances” has cropped up again!

In a brief statement, via social media, the organisers of the Ne-Yo concert said the decision was taken due to “unforeseen circumstances and factors beyond their control.”

Ne-Yo, too, subsequently made an announcement, citing “Unforeseen circumstances.”

The public has a right to know what these “unforeseen circumstances” are, and who is to be blamed – the organisers or Ne-Yo!

Ne-Yo’s management certainly need to come out with the truth.

However, those who are aware of some of the happenings in the setup here put it down to poor ticket sales, mentioning that the tickets for the concert, and a meet-and-greet event, were exorbitantly high, considering that Ne-Yo is not a current mega star.

We also had a cancellation coming our way from Shah Rukh Khan, who was scheduled to visit Sri Lanka for the City of Dreams resort launch, and then this was received: “Unfortunately due to unforeseen personal reasons beyond his control, Mr. Khan is no longer able to attend.”

Referring to this kind of mess up, a leading showbiz personality said that it will only make people reluctant to buy their tickets, online.

“Tickets will go mostly at the gate and it will be very bad for the industry,” he added.

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoLankan aircrew fly daring UN Medevac in hostile conditions in Africa

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRethinking post-disaster urban planning: Lessons from Peradeniya

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoAre we reading the sky wrong?

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo