Features

The DUNF gathers steam; Lalith & Gamini find leadership compromise

Organizing big rallies, contacts with Denzil Kobbekaduwa

(Excerpted from vol. 3 of the Sarath Amunugama autbiography)

There was such a big demand for our public rallies that we planned to hold two large meetings every week in addition to other small electorate based meetings. The upshot of our popularity was that even SLFPers, including some of their leaders, were seen at our meetings. Many of them preferred to keep a distance by remaining in the periphery of the meeting grounds. But some others, particularly those who had distanced themselves from their party infighting, figured more prominently by getting on to our stage.

There was such a big demand for our public rallies that we planned to hold two large meetings every week in addition to other small electorate based meetings. The upshot of our popularity was that even SLFPers, including some of their leaders, were seen at our meetings. Many of them preferred to keep a distance by remaining in the periphery of the meeting grounds. But some others, particularly those who had distanced themselves from their party infighting, figured more prominently by getting on to our stage.

For instance SD Bandaranayake, a grandee of SLFP battles from before 1956, indicated that he would come onto our stage in Gampaha and also address the meeting. This was a considerable victory for our fledgeling party as SDB was part of the radical, and anti UNP, history of Siyane Korale. We assembled at his “Madugaha Walawwe” in Gampaha for lunch and from there accompanied him to the meeting grounds where he received a rousing welcome. It was a memorable meeting for me also because I began addressing DUNF party rallies from the Gampaha meeting onwards. It was the beginning of a hectic speaking schedule which has since taken me to all parts of the country for close on 30 years.

Another leading SLFPer who helped us from behind the scenes was Bertie Dissanayake who was one of the political leaders of Anuradhapura district. Our local leaders had characterized Bertie as violence prone and we were somewhat apprehensive when Gamini, Premachandra and I were billed to speak at a meeting in his Kalawewa electorate. It was a largely attended meeting which was held in a scenic grounds overlooking a reservoir. We need not have worried since Bertie, who was seen driving about in a jeep in the vicinity, had asked his supporters not to obstruct us in anyway.

Since the Kalawewa electorate was one of the beneficiaries of the Mahaweli project there was a large gathering to greet Gamini. Bertie himself had earlier benefited from the ex-Mahaweli minister’s largesse. We were pleasantly surprised when many of the Mahaweli settlers met us after the meeting. Many of them had been selected from Kandyan villages for settlement in Kalawewa under the Mahaweli project. They insisted on our visiting the “Teldeniya Ela” or “Tumpane Ela” where they had been relocated after coming to the “Raja Rata”. It was nightfall when we got back to our vehicles after enjoying a Kandyan meal with them. Though they were UNP supporters earlier we were able to draft them into our new party. Several UNP MPs of the Rajarata like HGP Nelson helped us on the sly and even paid our hotel bills after the Polonnaruwa meeting.

I had a similar experience when we held a meeting in Hiniduma in the hilly periphery of Galle district. I attended this meeting with Gamini, Lalith and Premachandra. As a researcher with Gananath Obeyesekere in the sixties and later as Assistant Government Agent of Galle district I had worked with the villagers of Hiniduma and they turned up in strength at our meeting held in Neluwa. After listening to our leaders they insisted that I speak to them much to the delight of our organizer for Hiniduma electorate who found a welcome “block” of voters for his campaign in an electorate which had been a leftist stronghold. Here again we were fortunate that the UNP organizer Sarath Amarasiri was the son of MS Amarasiri who was Lalith’s deputy minister during the JRJ regime. He made no attempt to sabotage our meeting unlike many of Premadasa’s favourite MPs who confronted us in their bailiwicks.

Anuradhapura

The growing success of our meetings were reported to the President who was by now getting anxious and was preparing for a showdown. His opportunity came when we planned to hold a large rally in Anuradhapura. In order to capitalize on the large crowds that congregate there on religious holidays we had arranged to hold our meeting on a Poya day in a large playground. We were sure of a historic gathering and every effort was made to make it a major event. This must have been conveyed to Premadasa who banned the meeting by slapping a prohibitory order.

When the party leaders met at the Anuradhapura Resthouse, Police bigwigs came there with copies of the order and requested us to cancel the meeting. Following the President’s wishes they had been ordered by the IGP to stop the DUNF meeting at any cost. In the meanwhile our supporters were coming in from all parts of the country and were congregating in the new city area expecting to attend the rally. After a hurried consultation we decided that it would be a fatal blow to the party if we abandoned the meeting. However there was no doubt regarding the determination of the police to stop us. So we decided on a strategy of making it appear to be a religious gathering.

We divided our followers into four groups who wended their way from different directions to the Ruvanweliseya carrying baskets of flowers to be offered at the dagoba. Each group was led by party seniors who were to ensure that there was no violence. Fortunately a chief of a temple in Anuradhapura who was earlier an undergraduate at Vidyodaya University and a well known Sinhala lyric writer and a friend of mine, agreed to my request to come to the dagoba area to administer pansil thereby giving credence to our claims of religious devotion. This got us out of a difficult predicament as my friend the priest was well regarded by the police who then decided to stand by rather than confront us.

I can remember as an aside that the famous singer Gunadasa Kapuge, who was attached to the Raja Rata Radio, also joined us in an inebriated state and started chanting Buddhist stanzas much to the amusement of the audience. He had come to meet the priest and wandered into our meeting. We dispersed peacefully and held a press conference the following day in Colombo probably annoying the President who was spoiling for a fight and did not want a peaceful resolution in the sacred city. By this time the DUNF was beginning to attract much attention and was setting the political agenda by highlighting anti-government issues which the SLFP had been reluctant or unable to convey to the masses of voters who were now beginning to get disenchanted.

Denzil Kobbekaduwa

Gamini, Denzil Kobbekaduwa and I were friends from our time as students at Trinity College in Kandy. With the civil war sapping the growth momentum of the country the government was losing its popularity and many were turning to the army as a saviour of the integrity of the country. This was symbolized by the emergence of the charismatic Denzil K as a leader of the new national minded army. Earlier Army Commanders, however competent they may have been, were “Sandhurst types” who did not win national recognition. The SLFP and the DUNF were all praise for Denzil adding to the fears of Premadasa. All Sri Lankan presidents, including Mahinda Rajapaksa, were afraid of Army Commanders and were on the lookout for any suspicious move by the army top brass.

Mahinda Rajapaksa who got on well with army Commander Fonseka during the war later became apprehensive after the victorious army boss planned a massive celebratory jamboree in Colombo. Premadasa who knew of Denzil’s kinship links with the Ratwattes and personal friendship with several DUNF leaders, began to keep tabs on him though there was no open confrontation. Since Gamini was already under surveillance it was decided that Denzil should contact me with messages which I would then convey to the DUNF leaders. In addition to our Trinity connection my younger brother, Major General Asoka Amunugama, had served as Denzil’s ADC in the northern theatre.

I must emphasize here that although he told me about army plans to attack the LTTE, Denzil at no time appeared to be disloyal to the elected head of the country. He was personally concerned that the country was sliding towards further turmoil but he did not contemplate involving the army in national politics. However I had the distinct feeling in our discussions that he was thinking of a political role as a civilian once he retired from the army. His sympathies were with the DUNF and the SLFP and the opposition had no hesitation in referring to him as a politician in the making in their propaganda by constantly extolling his leadership qualities.

The President could be excused for thinking that Denzil will become a problem for him in the future. This does not mean that he plotted the army hero’s murder as the opposition whispered after the Aralai point debacle when Denzil, Wimalaratne and several other senior commanders of the army and navy were killed by the LTTE which had planted land mines on the terrain which was to be used to launch an amphibious landing across the lagoon. However it must be stated that the commanders were breaking their own rules that they should not travel together. Denzil and Wimalaratne were in the same jeep and paid the price. Before he left for Jaffna for this operation Denzil phoned me at home early in the morning and we agreed to have a meeting with Gamini once he returned after Aralai. Sadly it was not to be.

The death of Denzil, Wimalaratne and their staff led to a wave of hatred against Premadasa who hastily tried to win back sympathy by declaring a major road as Denzil Kobbakaduwa Mawatha to no avail. As opposition leaders we followed the cortege from his residence in Rosmead Place to Kanatte where there was a large gathering of people, some of whom were shouting slogans. This was followed by ugly scenes when well known supporters of Premadasa were manhandled. They fled to safety and one wrote later to say that he thought that he would be killed by the mob that day These incidents were game changers and the Premadasa government was fast losing its popularity. This compelled the President to take several strategic decisions which culminated with his murder by the LTTE only a week after the assassination of Lalith Athulathmudali.

Second Provincial Council Elections

The term of office of the first Provincial Councils were nearing its end and new elections were due in 1993. This created a dilemma for Premadasa since his popularity had plummeted. He also received information from his acolytes that the DUNF, which was gaining public favour, was locked into a battle for leadership which was eyed by both Lalith and Gamini. Gamini was senior but he was already in the doghouse when Lalith made a great sacrifice and left the Cabinet. He could have easily betrayed Gamini and earned Premadasa’s favour. Indeed even after the rupture Mrs. Hema Premadasa was busily engaged in trying to get Lalith back and isolating Gamini thereby weakening the DUNF and even driving it out of electoral contention. The President believed that the two ambitious leaders would fall out if he played for time. Such a rift would create the opportunity for him to call for a snap provincial council election. For us in the DUNF the opposite was true. We had to hold together and force an early election.

Lalith

Since I was acceptable to both leaders I was entrusted with finding a way to settle the leadership issue. A few us would meet in PBG Kalugalle’s house in Cambridge Terrace to find a way out. I remember that Ravi Karunanayake, who was part of Lalith’s entourage, coming to Gamin’s house on his old motorcycle to plead the case for his mentor. Our small group first decided that the first leader would hold office for six months of the year to be followed by the other who also will have a six month tenure. During the leadership of one the other would hold the office of national organizer and vice versa. This idea was acceptable to Lalith and Gamini. But the all important question of who would first ascend the “gadi” was left open for further discussion.

At this stage I suggested to Gamini that he should make a grand gesture by inviting Lalith to be the first leader. After all we would simultaneously announce that he will hold that office in six months time. Such a gesture would enhance his image and ensure the competitiveness of the DUNF in the forthcoming elections. A leadership impasse at this stage would weaken the party at a crucial testing time. With some reluctance Gamini agreed to my suggestion and I typed out the compromise formula.

I must say that Lalith who was the beneficiary of this formula behaved impeccably by thanking Gamini and consulting him every day on the progress of the party. He also, much to his rival’s relief, undertook the responsibility of collecting funds for the forthcoming electoral battle. This act of cooperation and reconciliation set shock waves in both the UNP and SLFP who were used to bitter internecine warfare in their recent history. I read recently in an interview given by a Lalith confidante that his leader was so moved by Gamini’s gesture that he had decided to nominate the latter for the Presidential bid and await his turn after Gamini’s term of office.

Premadasa’s Response

Within days of our announcement of satisfactory leadership arrangements a disappointed President Premadasa called for provincial council elections. He knew that with more time the DUNF would now grow in strength and cut into the UNPs membership as well as its vote bank. Our meetings were exceptionally successful and our “attack team” of Premachandra and Weerawanni was tearing up Premadasa’s image. It is also likely that the SLFP was looking on this contest with glee and were encouraging their members to attend our meetings to swell the crowds and thereby demoralize the UNP. We were in friendly competition and often worked together on human rights and media issues.

Premadasa who was unforgiving pulled out an old murder charge against Parliamentarian Lakshman Senewiratne who had joined he DUNF. He was remanded and locked up in Bogambara prison. We and the media took this issue up and organized a demonstration and motorcade in which Anura Bandaranaike of the SLFP joined us. This common front helped in winning many of the prison officials to our side who looked the other way when we sent food and other amenities to Lakshman from outside.

These gifts included a smart phone for him to speak to his family who were then in Australia. The phone was smuggled into his cell in a hollowed out birthday cake. Mrs. Bandaranaike herself was very cooperative and probably preferred to interact with us rather than some of her own party members like Mervyn Silva who humiliated her on the orders of the anti-Sirima faction of the SLFP. The SLFP was in turmoil with Anura loyalists fighting tooth and nail to keep Chandrika out of the Central Committee of the party though Mrs. B wanted her in. CBK was a new face and the wife of the late Vijaya Kumaratunga. She with her obvious sincerity and commitment was rejuvenating the SLFP.

I was researching with ICES at that time and remember the enthusiasm with which Neelan Tiruchelvam and his group were promoting the “new political star” on the horizon. I was a speaker at a seminar organised by ICES at which CBK was also invited to be a speaker. As usual she was late, but when she did turn up there was such a “buzz”in the audience which clearly indicated that she had “star quality”and would figure in the political struggle to come. By this time she had a

faction in the SLFP led by Ratnasiri Wickremanayake, Mangala Samaraweera and S. B. Dissanayake who were engaged in promoting her with the blessings of Mrs. B.

Features

Hanoi’s most popular street could kill you

Train Street started life as a razor-thin alley with a train rushing through it. Now, it’s swarmed with Instagrammable cafes and tourists who can’t stay away, despite the risks.

A train chugs through Hanoi, approaching a narrow passageway festooned with Chinese-style lanterns. Just as it screams into the station, a tourist jumps onto the tracks, attempting her most social-media friendly pose. Moments before the train strikes, its horn blaring into the humid air, she recoils to safety. Click, post.

It’s just an ordinary day on Hanoi’s Train Street, a 400m stretch of railway flanked by cafes where tourists nurse beers and watch, mesmerised, as trains roar past them at dangerously close proximity: sometimes crashing into tables and chairs.

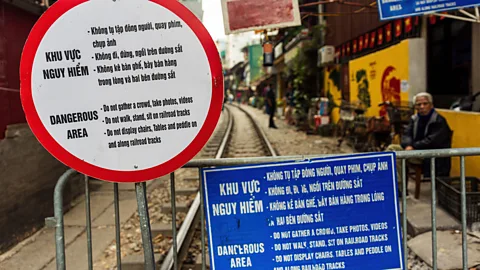

Fun? Evidently – in a few short years, Train Street has entered Vietnam’s pantheon of “must-see” attractions, along with Ha Long Bay and the Cu Chi Tunnels. But the Vietnamese government is less impressed; since the site went viral in 2017, it has attempted various shutdowns, first in 2019, then 2022 and most recently further investigations and crackdowns in 2025 after an incident where a selfie-snapping tourist was nearly dragged under an oncoming train’s wheels. Police barricades go up between train arrivals; edicts are issued to tour operators and bar owners.

The tourists come anyway.

How did an ordinary street become one of Vietnam’s hottest tourist attractions? It started innocently enough.

The North-South Railway was built by colonialist French forces in 1902, connecting Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City. Fifty-four years later, the General Department of Railway erected a series of squat buildings straddling a stretch in central Hanoi to house employees. By the 1970s, the area was considered a slum; residents regularly roused out of their sleep by trains rumbling through, their houses quaking.

“It was just an ordinary street with train tracks running through it,” said Minh Anh, a lifelong Hanoi local who works at local whisky distillery,

Alamy The Vietnamese government has attempted numerous shutdowns of the area (Credit: Alamy)Alamy

The Vietnamese government has attempted numerous shutdowns of the area (Credit: Alamy)

From ordinary to unmissable

How did an ordinary street become one of Vietnam’s hottest tourist attractions? It started innocently enough.

The North-South Railway was built by colonialist French forces in 1902, connecting Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City. Fifty-four years later, the General Department of Railway erected a series of squat buildings straddling a stretch in central Hanoi to house employees. By the 1970s, the area was considered a slum; residents regularly roused out of their sleep by trains rumbling through, their houses quaking.

“It was just an ordinary street with train tracks running through it,” said Minh Anh, a lifelong Hanoi local who works at local whisky distillery, Về Để Đi’. “When it started popping up all over social media, I was honestly surprised.”

Nhi Nguyn, a tour guide for A Taste of Hanoi, used to walk tourists through, just before it exploded in popularity. “People were still living ordinary lives there back then and there weren’t so many cafes next to the tracks,” she said. “It had a much more authentic feel: scooters were locked up just meters from the tracks, laundered clothes hung outside, and people were cooking outside on small gas stoves.”

. “When it started popping up all over social media, I was honestly surprised.”

Nhi Nguyn, a tour guide for

Alamy The Vietnamese government has attempted numerous shutdowns of the area (Credit: Alamy)Alamy

The Vietnamese government has attempted numerous shutdowns of the area (Credit: Alamy)

From ordinary to unmissable

How did an ordinary street become one of Vietnam’s hottest tourist attractions? It started innocently enough.

The North-South Railway was built by colonialist French forces in 1902, connecting Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City. Fifty-four years later, the General Department of Railway erected a series of squat buildings straddling a stretch in central Hanoi to house employees. By the 1970s, the area was considered a slum; residents regularly roused out of their sleep by trains rumbling through, their houses quaking.

“It was just an ordinary street with train tracks running through it,” said Minh Anh, a lifelong Hanoi local who works at local whisky distillery, Về Để Đi’. “When it started popping up all over social media, I was honestly surprised.”

Nhi Nguyn, a tour guide for A Taste of Hanoi, used to walk tourists through, just before it exploded in popularity. “People were still living ordinary lives there back then and there weren’t so many cafes next to the tracks,” she said. “It had a much more authentic feel: scooters were locked up just meters from the tracks, laundered clothes hung outside, and people were cooking outside on small gas stoves.”

, used to walk tourists through, just before it exploded in popularity. “People were still living ordinary lives there back then and there weren’t so many cafes next to the tracks,” she said. “It had a much more authentic feel: scooters were locked up just meters from the tracks, laundered clothes hung outside, and people were cooking outside on small gas stoves.”

In early 2013, Colm Pierce and Alex Sheal, co-founders of Hanoi-based photography tours Vietnam in Focus, launched a Hanoi on the Tracks tour to show visitors how local residents had adopted to the locomotive-sized challenge of living on railway tracks. Serendipitously, in June 2013, Instagram launched its new video-sharing feature. A year later, the Travel Channel show “Tough Trains” featured Pierce walking down Train Street with a camera crew, further enticing travellers.

In 2017, an enterprising resident started selling beer and coffee, inviting curious tourists to stay to watch the train go by. Neighbours noticed the economic opportunity and cafes and bars rapidly spread. Soon, the formerly derelict alley, now dubbed Phố Đường Tàu (literally: “Train Street”) became bedecked with colourful lanterns and Christmas lights. Visitors learned to time their arrival for 30 minutes before a scheduled train and the “classic” Train Street experience was cemented: upon entering the tracks, tourists were shepherded into rail-side bars by local merchants and plied with beers and coffee, until the train shrieked through, rattling plates and causing hearts to pound.

Julia Husum, a university student from Norway, visited Train Street in February 2026, and “loved” the experience. “We put our beer caps on the railway, and the train flattened it, creating souvenirs for us,” she said. “I’d go back again.”

Without the advent of social media, would Train Street have become popular? As a travel writer, I’ve witnessed dozens of would-be influencers’ death-defying acts, like scaling down a rocky cliff above Dubrovnik and standing atop the side wall of 14th-Century Charles Bridge in Prague; wistfully looking off into the distance as the camera flashes. I’ve come to conclude that Train Street is no different; here, too, visitors risk their own safety for a picture-perfect opportunity.

“Essentially social media has fuelled Train Street into what it is today, [where] tourists flock in droves to the area to feel the adrenaline of the passing train while sipping local coffee,” echoed Michael Stanbury, the creative director for Vietnam in Focus. “Even without the train, the Instagrammable decorated street holds a very Hanoian charm.”

Local debate; the government proposes halting passenger trains for good. And each attempted shutdown, tourists climb past the barricades. There are, to date, more than 100,000 posts tagging Train Street on Instagram. Men’s grooming blogger Adam Hurly visited because a friend had hyped it. “It felt more like an Instagram attraction rather than a neighbourhood street,” he admitted, noting that once the crowds arrive, it becomes congested and less enjoyable, “Especially if you’re just standing on the main sidewalk trying to get a picture.”

He added: “It’s one of those places that looks better in photos than it feels in reality.”

But Matthew Tran, an artisanal footwear designer who visits Hanoi regularly, loves the pull of Train Street.

“The coffees were absurdly overpriced, yet I paid for them every time because I couldn’t stop marvelling at how the place worked; how an entire economy could thrive in such an improbable space,” he said. “These vendors built something real out of something most people would call chaos – that, to me, is worth coming back for.”

He offers advice for future visitors: “It’s a unique experience you won’t get anywhere else. Although I wish more visitors would stop for a moment and remember that while it’s a tourist attraction to them, living beside those train tracks is someone else’s daily reality.”

Under more superficial reasons, visiting Train Street is similar to the appeal of visiting the Eiffel Tower during someone’s first visit to Paris, said Charlotte Russell, founder of The Travel Psychologist.

“Humans are a social species and if we perceive that other people are enjoying an experience, it is natural for us to want to do it too,” she said. “This goes back to our evolution, when we lived in small groups and it would be advantageous for us to emulate other people in this way. So the sense of fear of missing out that we experience when seeing other people visiting places like Train Street is part of being human.”

Bearix Stewart-Frommer, an American pre-med student, validates Russell’s theory: “I found out about Train Street from my mum,” she said. “I didn’t have some deep motivation to see it, but I was curious because it’s one of those quirky, very photogenic spots that people talk about on social media.”

But there may be a more deep-seated reason why we’re lured to such places, Russell notes: “With Train Street specifically, the risk element is part of what makes it so novel, especially those of us from countries like the UK… We are used to regulation and precaution, railings, barriers and painted lines that we must stand behind. In contrast, Train Street can feel unbelievable to see and experience… [it helps] us reflect on our own norms and realise that other perspectives do exist.”

Local tour guide Phuong Loan Ngo offers one such alternative perspective: “The economic boost is undeniable, giving families who live along Train Street financial opportunities,” she said. “On the other hand, there are cultural challenges too. When an area becomes a ‘spotlight’ for social media, a place’s historical and cultural heritage can get lost. Instead of learning about how this railway has functioned since the colonial era, people often leave with only a photo, missing the true soul of the neighbourhood.”

The irony is that Vietnam in Focus has now moved their photography tours to another, far-less trammelled part of the railway, so they can show visitors that old, track-side way of life.

“As with all good things, the popularity of Train Street and the crowds it attracts are spreading,” said Sheal. “Thankfully, we have scoured Hanoi and found a fantastic local market that runs along the Hanoian railway further out in the suburbs – a new attraction.”

That is, until the social-media-obsessed travel masses find out about it. For better or worse, the unbearable lightness of Train Street is a permanent, but moveable feast.

[BBC]

Features

An innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

After nearly two decades of on-and-off negotiations that began in 2007, India and the European Union formally finally concluded a comprehensive free trade agreement on 27 January 2026. This agreement, the India–European Union Free Trade Agreement (IEUFTA), was hailed by political leaders from both sides as the “mother of all deals,” because it would create a massive economic partnership and greatly increase the current bilateral trade, which was over US$ 136 billion in 2024. The agreement still requires ratification by the European Parliament, approval by EU member states, and completion of domestic approval processes in India. Therefore, it is only likely to come into force by early 2027.

An Innocent Bystander

When negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement between India and the European Union were formally launched in June 2007, anticipating far-reaching consequences of such an agreement on other developing countries, the Commonwealth Secretariat, in London, requested the Centre for Analysis of Regional Integration at the University of Sussex to undertake a study on a possible implication of such an agreement on other low-income developing countries. Thus, a group of academics, led by Professor Alan Winters, undertook a study, and it was published by the Commonwealth Secretariat in 2009 (“Innocent Bystanders—Implications of the EU-India Free Trade Agreement for Excluded Countries”). The authors of the study had considered the impact of an EU–India Free Trade Agreement for the trade of excluded countries and had underlined, “The SAARC countries are, by a long way, the most vulnerable to negative impacts from the FTA. Their exports are more similar to India’s…. Bangladesh is most exposed in the EU market, followed by Pakistan and Sri Lanka.”

Trade Preferences and Export Growth

Normally, reduction of price through preferential market access leads to export growth and trade diversification. During the last 19-year period (2015–2024), SAARC countries enjoyed varying degrees of preferences, under the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP). But, the level of preferential access extended to India, through the GSP (general) arrangement, only provided a limited amount of duty reduction as against other SAARC countries, which were eligible for duty-free access into the EU market for most of their exports, via their LDC status or GSP+ route.

However, having preferential market access to the EU is worthless if those preferences cannot be utilised. Sri Lanka’s preference utilisation rate, which specifies the ratio of eligible to preferential imports, is significantly below the average for the EU GSP receiving countries. It was only 59% in 2023 and 69% in 2024. Comparative percentages in 2024 were, for Bangladesh, 96%; Pakistan, 95%; and India, 88%.

As illustrated in the table above, between 2015 and 2024, the EU’s imports from SAARC countries had increased twofold, from US$ 63 billion in 2015 to US$ 129 billion by 2024. Most of this growth had come from India. The imports from Pakistan and Bangladesh also increased significantly. The increase of imports from Sri Lanka, when compared to other South Asian countries, was limited. Exports from other SAARC countries—Afghanistan, Bhutan, Nepal, and the Maldives—are very small and, therefore, not included in this analysis.

Why the EU – India FTA?

With the best export performance in the region, why does India need an FTA with the EU?

Because even with very impressive overall export growth, in certain areas, India has performed very poorly in the EU market due to tariff disadvantages. In addition to that, from January 2026, the EU has withdrawn GSP benefits from most of India’s industrial exports. The FTA clearly addresses these challenges, and India will improve her competitiveness significantly once the FTA becomes operational.

Then the question is, what will be its impact on those “innocent bystanders” in South Asia and, more particularly, on Sri Lanka?

To provide a reasonable answer to this question, one has to undertake an in-depth product-by-product analysis of all major exports. Due to time and resource constraints, for the purpose of this article, I took a brief look at Sri Lanka’s two largest exports to the EU, viz., the apparels and rubber-based products.

Fortunately, Sri Lanka’s exports of rubber products will be only nominally impacted by the FTA due to the low MFN duty rate. For example, solid tyres and rubber gloves are charged very low (around 3%) MFN duty and the exports of these products from Sri Lanka and India are eligible for 0% GSP duty at present. With an equal market access, Sri Lanka has done much better than India in the EU market. Sri Lanka is the largest exporter of solid tyres to the EU and during 2024 our exports were valued at US$180 million.

On the other hand, Tariffs MFN tariffs on Apparel at 12% are relatively high and play a big role in apparel sourcing. Even a small difference in landed cost can shift entire sourcing to another supplier country. Indian apparel exports to the EU faced relatively high duties (8.5% – 12%), while competitors, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, are eligible for preferential access. In addition to that, Bangladesh enjoys highly favourable Rules of Origin in the EU market. The impact of these different trade rules, on the EU’s imports, is clearly visible in the trade data.

During the last 10 years (2015-2024), the EU’s apparel imports from Bangladesh nearly doubled, from US$15.1 billion, in 2015, to US$29.1 billion by 2024, and apparel imports from Pakistan more than doubled, from US$2.3 billion to US$5.5 billion. However, apparel imports from Sri Lanka increased only from US$1.3 billion in 2015 to US$2.2 billion by 2024. The impressive export growth from Pakistan and Bangladesh is mostly related to GSP preferences, while the lackluster growth of Sri Lankan exports was largely due to low preference utilisation. Nearly half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports faced a 12% tariff due to strict Rules of Origin requirements to qualify for GSP.

During the same period, the EU’s apparel imports from India only showed very modest growth, from US$ 5.3 billion, in 2015, to US$ 6.3 billion in 2024. The main reason for this was the very significant tariff disadvantage India faced in the EU market. However, once the FTA eliminates this gap, apparel imports from India are expected to grow rapidly.

According to available information, Indian industry bodies expect US$ 5-7 billion growth of textiles and apparel exports during the first three years of the FTA. This will create a significant trade diversion, resulting in a decline in exports from China and other countries that do not enjoy preferential market access. As almost half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports are not eligible for GSP, the impact on our exports will also be fierce. Even in the areas where Sri Lanka receives preferential duty-free access, the arrival of another large player will change the market dynamics greatly.

A Passive Onlooker?

Since the commencement of the negotiations on the EU–India FTA, Bangladesh and Pakistan have significantly enhanced the level of market access through proactive diplomatic interventions. As a result, they have substantially increased competitiveness and the market share within the EU. This would help them to minimize the adverse implications of the India–EU FTA on their exports. Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU market have not performed that well. The challenges in that market will intensify after 2027.

As we can clearly anticipate a significant adverse impact from the EU-India FTA, we should start to engage immediately with the European Commission on these issues without being passive onlookers. For example, the impact of the EU-India FTA should have been a main agenda item in the recently concluded joint commission meeting between the European Commission and Sri Lanka in Colombo.

Need of the Hour – Proactive Commercial Diplomacy

In the area of international trade, it is a time of turbulence. After the US Supreme Court judgement on President Trump’s “reciprocal tariffs,” the only prediction we can make about the market in the United States market is its continued unpredictability. India concluded an FTA with the UK last May and now the EU-India FTA. These are Sri Lanka’s largest markets. Now to navigate through these volatile, complex, and rapidly changing markets, we need to move away from reactive crisis management mode to anticipatory action. Hence, proactive commercial diplomacy is the need of the hour.

(The writer can be reached at senadhiragomi@gmail.com)

By Gomi Senadhira

Features

Educational reforms: A perspective

Dr. B.J.C. Perera (Dr. BJCP) in his article ‘The Education cross roads: Liberating Sri Lankan classroom and moving ahead’ asks the critical question that should be the bedrock of any attempt at education reform – ‘Do we truly and clearly understand how a human being learns? (The Island, 16.02.2026)

Dr. BJCP describes the foundation of a cognitive architecture taking place with over a million neural connections occurring in a second. This in fact is the result of language learning and not the process. How do we ‘actually’ learn and communicate with one another? Is a question that was originally asked by Galileo Galilei (1564 -1642) to which scientists have still not found a definitive answer. Naom Chomsky (1928-) one of the foremost intellectuals of our time, known as the father of modern linguistics; when once asked in an interview, if there was any ‘burning question’ in his life that he would have liked to find an answer for; commented that this was one of the questions to which he would have liked to find the answer. Apart from knowing that this communication takes place through language, little else is known about the subject. In this process of learning we learn in our mother tongue and it is estimated that almost 80% of our learning is completed by the time we are 5 years old. It is critical to grasp that this is the actual process of learning and not ‘knowledge’ which tends to get confused as ‘learning’. i.e. what have you learnt?

The term mother tongue is used here as many of us later on in life do learn other languages. However, there is a fundamental difference between these languages and one’s mother tongue; in that one learns the mother tongue- and how that happens is the ‘burning question’ as opposed to a second language which is taught. The fact that the mother tongue is also formally taught later on, does not distract from this thesis.

Almost all of us take the learning of a mother tongue for granted, as much as one would take standing and walking for granted. However, learning the mother tongue is a much more complex process. Every infant learns to stand and walk the same way, but every infant depending on where they are born (and brought up) will learn a different mother tongue. The words that are learnt are concepts that would be influenced by the prevalent culture, religion, beliefs, etc. in that environment of the child. Take for example the term father. In our culture (Sinhala/Buddhist) the father is an entity that belongs to himself as well as to us -the rest of the family. We refer to him as ape thaththa. In the English speaking (Judaeo-Christian) culture he is ‘my father’. ‘Our father’ is a very different concept. ‘Our father who art in heaven….

All over the world education is done in one’s mother tongue. The only exception to this, as far as I know, are the countries that have been colonised by the British. There is a vast amount of research that re-validates education /learning in the mother tongue. And more to the point, when it comes to the comparability of learning in one’s own mother tongue as opposed to learning in English, English fails miserably.

Education /learning is best done in one’s mother tongue.

This is a fact. not an opinion. Elegantly stated in the words of Prof. Tove Skutnabb-Kangas-“Mother tongue medium education is controversial, but ‘only’ politically. Research evidence about it is not controversial.”

The tragedy is that we are discussing this fundamental principle that is taken for granted in the rest of the world. It would not be not even considered worthy of a school debate in any other country. The irony of course is, that it is being done in English!

At school we learnt all of our subjects in Sinhala (or Tamil) right up to University entrance. Across the three streams of Maths, Bio and Commerce, be it applied or pure mathematics, physics, chemistry, zoology, botany economics, business, etc. Everything from the simplest to the most complicated concept was learnt in our mother tongue. An uninterrupted process of learning that started from infancy.

All of this changed at university. We had to learn something new that had a greater depth and width than anything we had encountered before in a language -except for a very select minority – we were not at all familiar with. There were students in my university intake that had put aside reading and writing, not even spoken English outside a classroom context. This I have been reliably informed is the prevalent situation in most of the SAARC countries.

The SAARC nations that comprise eight countries (Sri Lanka, Maldives, India, Pakistan Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan) have 21% of the world population confined to just 3% of the earth’s land mass making it probably one of the most densely populated areas in the world. One would assume that this degree of ‘clinical density’ would lead to a plethora of research publications. However, the reality is that for 25 years from 1996 to 2021 the contribution by the SAARC nations to peer reviewed research in the field of Orthopaedics and Sports medicine- my profession – was only 1.45%! Regardless of each country having different mother tongues and vastly differing socio-economic structures, the common denominator to all these countries is that medical education in each country is done in a foreign language (English).

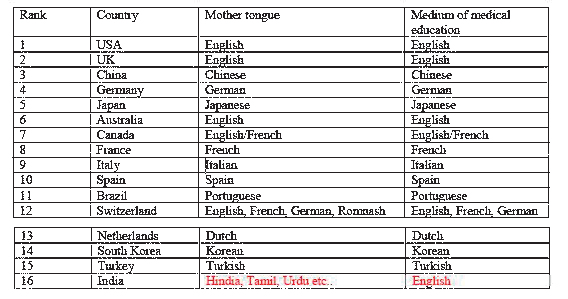

The impact of not learning in one’s mother tongue can be illustrated at a global level. This can be easily seen when observing the research output of different countries. For example, if one looks at orthopaedics and sports medicine (once again my given profession for simplicity); Table 1. shows the cumulative research that has been published in peer review journals. Despite now having the highest population in the world, India comes in at number 16! It has been outranked by countries that have a population less than one of their states. Pundits might argue giving various reasons for this phenomenon. But the inconvertible fact remains that all other countries, other than India, learn medicine in their mother tongue.

(See Table 1) Mother tongue, medium of education in country rank order according to the volume of publications of orthopaedics and sports medicine in peer reviewed journals 1996 to 2024. Source: Scimago SCImago journal (https://www.scimagojr.com/) has collated peer review journal publications of the world. The publications are categorized into 27 categories. According to the available data from 1996 to 2024, China is ranked the second across all categories with India at the 6th position. China is first in chemical engineering, chemistry, computer science, decision sciences, energy, engineering, environmental science, material sciences, mathematics, physics and astronomy. There is no subject category that India is the first in the world. China ranks higher than India in all categories except dentistry.

The reason for this difference is obvious when one looks at how learning is done in China and India.

The Chinese learn in their mother tongue. From primary to undergraduate and postgraduate levels, it is all done in Chinese. Therefore, they have an enormous capacity to understand their subject matter just not itself, but also as to how it relates to all other subjects/ themes that surround it. It is a continuous process of learning that evolves from infancy onwards, that seamlessly passes through, primary, secondary, undergraduate and post graduate education, research, innovation, application etc. Their social language is their official language. The language they use at home is the language they use at their workplaces, clubs, research facilities and so on.

In India higher education/learning is done in a foreign language. Each state of India has its own mother tongue. Be it Hindi, Tamil, Urdu, Telagu, etc. Infancy, childhood and school education to varying degrees is carried out in each state according to their mother tongue. Then, when it comes to university education and especially the ‘science subjects’ it takes place in a foreign tongue- (English). English remains only as their ‘research’ language. All other social interactions are done in their mother tongue.

India and China have been used as examples to illustrate the point between learning in the mother tongue and a foreign tongue, as they are in population terms comparable countries. The unpalatable truth is that – though individuals might have a different grasp of English- as countries, the ability of SAARC countries to learn and understand a subject in a foreign language is inferior to the rest of the world that is learning the same subject in its mother tongue. Imagine the disadvantage we face at a global level, when our entire learning process across almost all disciplines has been in a foreign tongue with comparison to the rest of the world that has learnt all these disciplines in their mother tongue. And one by-product of this is the subsequent research, innovation that flows from this learning will also be inferior to the rest of the world.

All this only confirms what we already know. Learning is best done in one’s mother tongue! .

What needs to be realised is that there is a critical difference between ‘learning English’ and ‘learning in English’. The primary-or some may argue secondary- purpose of a university education is to learn a particular discipline, be it medicine, engineering, etc. The students- have been learning everything up to that point in Sinhala or Tamil. Learning their discipline in their mother tongue will be the easiest thing for them. The solution to this is to teach in Sinhala or Tamil, so it can be learnt in the most efficient manner. Not to lament that the university entrant’s English is poor and therefore we need to start teaching English earlier on.

We are surviving because at least up to the university level we are learning in the best possible way i.e. in our mother tongue. Can our methods be changed to be more efficient? definitely. If, however, one thinks that the answer to this efficient change in the learning process is to substitute English for the mother tongue, it will defeat the very purpose it is trying to overcome. According to Dr. BJCP as he states in his article; the current reforms of 2026 for the learning process for the primary years, centre on the ‘ABCDE’ framework: Attendance, Belongingness, Cleanliness, Discipline and English. Very briefly, as can be seen from the above discussion, if this is the framework that is to be instituted, we should modify it to ABCDEF by adding a F for Failure, for completeness!

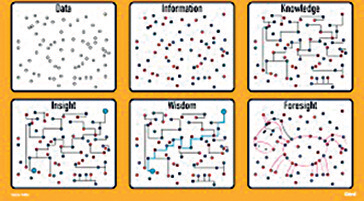

(See Figure 1) The components and evolution of learning: Data, information, knowledge, insight, wisdom, foresight As can be seen from figure 1. data and information remain as discrete points. They do not have interconnections between them. It is these subsequent interconnections that constitute learning. And these happen best through the mother tongue. Once again, this is a fact. Not an opinion. We -all countries- need to learn a second language (foreign tongue) in order to gather information and data from the rest of the world. However, once this data/ information is gathered, the learning needs to happen in our own mother tongue.

Without a doubt English is the most universally spoken language. It is estimated that almost a quarter of the world speaks English as its mother tongue or as a second language. I am not advocating to stop teaching English. Please, teach English as a second language to give a window to the rest of the world. Just do not use it as the mode of learning. Learn English but do not learn in English. All that we will be achieving by learning in English, is to create a nation of professionals that neither know English well nor their subject matter well.

If we are to have any worthwhile educational reforms this should be the starting pivotal point. An education that takes place in one’s mother tongue. Not instituting this and discussing theories of education and learning and proposing reforms, is akin to ‘rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic’. Sadly, this is not some stupendous, revolutionary insight into education /learning. It is what the rest of the world has been doing and what we did till we came under British rule.

Those who were with me in the medical faculty may remember that I asked this question then: Why can’t we be taught in Sinhala? Today, with AI, this should be much easier than what it was 40 years ago.

The editorial of this newspaper has many a time criticised the present government for its lackadaisical attitude towards bringing in the promised ‘system change’. Do this––make mother tongue the medium of education /learning––and the entire system will change.

by Dr. Sumedha S. Amarasekara

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoBathiya & Santhush make a strategic bet on Colombo

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoSeeing is believing – the silent scale behind SriLankan’s ground operation

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoBarking up the wrong tree