Features

Taking Sri Lanka Forward- Excerpts from C. Narayanasuwami’s “Managing Development: People, Policies and Institutions

Confronting issues of debt restructuring, economic stability and sustainability- a long-term perspective

Sri Lanka’s financial crisis has created greater awareness of the need for financial, economic and institutional reform and the development of a holistic approach to the planning, implementation and monitoring of economic and social policies and programs. Substantial efforts have been made in Sri Lanka for over one year or so to restructure debt and increase revenues but the conditions for long-term economic stability are yet to be fully addressed as these require multi-faceted initiatives at different levels. Reform measures are unlikely to be implemented expeditiously given the current socioeconomic pressures. Any reform initiatives will be time consuming and will require political cohesion and commitment.

The visit of the IMF team this month will throw some light on measures to be adopted with immediate and long-term results orientation.It would be prudent to think in terms of overall structural changes, some requiring immediate attention and others planned for a longer-term intervention. Looking at similar emergencies encountered in South America, South Africa and Asian countries such as Pakistan a number of short and long-term structural changes are warranted. Do the current programs, policies and the institutional framework provide adequate flexibility to enhance public sector performance, governance mechanisms and institutional capacity to address stabilisation issues? We had reviewed a few books and reports on economic management and found that considerable efforts need to be made to bring the country to sustainable levels of economic performance.

We reviewed, among others, a recent publication authored by a Sri Lankan Asian Development Bank Professional, Mr. C. Narayanasuwami, previously of the Ceylon Civil Service who last headed the then Agrarian Research and Training Institute (now known as Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training Institute) prior to joining the international civil service.

The book was released simultaneously in Colombo, Manila and Sydney. Some of the key aspects covered in the book entitled, ‘Managing Development: People, Policies and Institutions’ apply to the situation in several developing countries in the Asia-Pacific region with a few areas specifically addressing issues of particular relevance to Sri Lanka. Governance. The section on Governance, for example, deals primarily with the Sri Lankan situation and acknowledges that ‘sound governance would require (i) an effective policy framework, (ii) a qualified, competent, trained, and skilled workforce at different levels, (iii) an appropriate emoluments and salary structure that takes into account differences in performance levels, (v) a corruption free management system, and (vi) an overall politico-legal framework that supports non-discriminatory policies and promotes initiative and dynamism in project and program execution.

Evidently, transparency, predictability, accountability, stakeholder participation, rule of law, an efficient and uncorrupted public service, independence of judiciary, and media freedom, among others, are vital components of good governance. Sri Lanka has suffered substantially in upholding many of these values largely due to the adoption of undemocratic and often ill-conceived policies and practices in implementing varied development programs. No significant changes have occurred to reverse the culture of corruption and public sector inefficiencies and instil discipline in the maintenance of law and order’.

Public Sector Performance. Reference is made to the deterioration of public service standards in Sri Lanka and the following excerpt captures the current weaknesses that impede development performance.‘Over the past 30 years, about 40 percent of development projects failed to achieve their intended objectives within the stipulated time frames or within the expected budgetary allocations because of the lack of capacity to plan, implement, and deliver in a coordinated and integrated manner.

Some of the major factors that contributed to this situation are identified as follows; (i) politicization of the public service, (ii) lack of an enabling environment for improving performance, (iii) inadequate punitive strategies, (iv) inconsistent recruitment standards for public services, (v) inadequacies in the compensation and benefit packages, (vi) disproportionate expansion in the public sector-at present at least one-third of the public sector personnel are considered as superfluous and (vii) ethnic conflict and its debilitating impact on public sector morale’.

‘The politicization of the public service initially arose out of a felt need, largely driven by the desire to transform a highly elitist pro-western bureaucracy to meet the demands of a nation that had emerged from the shackles of colonialism. However, when public servants used this opportunity to seek favours and ignore tradition-bound value systems and ethical conduct, a service that built its reputation on its ability to withstand political pressures, maintain impartiality, objectivity and transparency in its dealings since the time of the British rule, began to crumble.

Loyalty was linked to political parties and individuals rather than to institutions and programs’. We consider the situation a major impediment to implementation of vital development projects. Capacity for decision-making is virtually non-existent due to the politicisation of the public sector. A radical transformation of the public sector is called for. Capacity Constraints. The book identifies capacity constraints as a major impediment to project/program implementation and provides some insights based on ADB experience in developing countries.

ADB has defined capacity as ‘strengthening the national framework within a developing member country (DMC) that affects the direction, management, and sustenance of the development process in a sector and the economy as a whole’. ‘In recent years ADB has linked capacity building closely with governance and has emphasized that good governance implies the capacity to provide citizens with an acceptable level of public services in an effective and efficient manner. Despite efforts made by multilateral agencies capacity constraints continue to pose challenges to development initiatives, as proven in Sri Lanka.

The limited success is attributable to shortcomings in the approaches adopted and the inability of countries like Sri Lanka to change, adapt, adjust and learn from lessons of experience’. The book refers to the efforts made and states as follows; ‘Over the years, a substantial number of development projects in most of the sectors failed to realise their full potential due to inadequate implementation capacities.

Evidence suggests that funds allocated by multilateral agencies lapsed on several occasions due to less than satisfactory disbursement processes, The factors that impeded more effective utilization of foreign aid is summarised as follows;(i)inadequate understanding of management systems, including a thorough understanding of the broad based objectives and goals of projects/programs, (ii) rigidity of policy structures that were bound by archaic regulations irrelevant to modern concepts of management, (iii) presence of multiple institutions whose roles overlapped with one another making decision making difficult because of conflicts that had political undertones, (iv) inadequate monitoring of development operations that had high foreign equity and funding support, and (v) weak public accountability and transparency that raised concerns among donors, and inadequate counterpart budget provisions.

Overall, lack of a results-based management system, complex administrative procedures, poor policy and institutional environment, weak procurement systems, and inadequate counterpart budget provisions contributed to the slow absorption of aid resources’.

The above excerpts coincide with some of the management shortcomings identified by the World Bank and the IMF in their deliberations with the Government in recent months.A major area identified as a constraint to development operations by international donors is the weak institutional capacity of implementing agencies. The book has a lot to offer in this regard and some useful excerpts are provided below;

Institution Building

. ‘institution building is aimed at strengthening capabilities for planning, organising, implementing, monitoring and evaluating development projects and programs sponsored by public, private, or grassroots level organisations. The major focus of governments should be on the approaches and issues related to increasing the capability of development institutions to make effective use of available human, physical, and financial resources.

The strengths and weaknesses of institutions as well as behavioural factors have often influenced the nature and pace of the development process. Many failures in development projects are not only due to production or technological inadequacies but also to institutional deficiencies, largely because self-sustaining capacity to implement projects is not emphasized at the time of project formulation. Studies of rural development in Asia have confirmed that inadequacies in the institutional framework have hindered the effective implementation of rural development programs’.

‘Institutional development has been impeded by shortages of trained staff, including competent middle-level managers who could provide the leadership to manage development projects. The available key staff are often burdened with multiple assignments and are denied the opportunity to provide the required focus and direction for project implementation.

The designers of complex projects do not examine thoroughly the capacities of each agency to implement complex components. Programs that depend on key individuals had collapsed when they left and equivalent replacements were not found. This raises the question of leadership and the importance of formulating appropriate policies and procedures for attracting and retaining staff in developing countries’.

The foregoing analysis covers a large number of countries in the Asia-Pacific region. It applies to the situation in Sri Lanka as well and though senior politicians and administrators are aware of the issues highlighted, very little has been done to address the issues primarily due to the lack of political will to institute radical change in the approaches to institutional reform. Little has been done up to date to transform the overall institutional framework. It is realised that the most important element in institution building is leadership but the efforts made to redress this inadequacy have had disastrous results. Nothing short of a substantial change to the institutional framework will remedy this situation’.

Leadership.

The book provides some insights into the role of leadership to provide the right impetus to improve managerial capability and to eventual success in project/program delivery. We quote some extracts below;

‘The most important element in institution building is leadership because change processes require intensive, skilful, and highly committed management, both of internal and of environmental relationships.

Managing uncertainty is part of the process of leadership and this requires immense skills and capacity for organisational learning. It is said that leadership is many things. It is meticulously shifting the attention of the institution through the mundane language of management systems. It is altering agenda so that new priorities get enough attention. It is being visible when things are going awry and invisible when they are working well. It is building a loyal team at the top that speaks more or less with one voice. Leadership does not refer to mere exercise of power but motivating, mobilizing, and transforming a group of individuals engaged in a common task to deliver effectively and efficiently the overall output expected of the agency.

Project completion reports and audits of completed projects undertaken by multilateral agencies have documented the success and failure of projects that have benefitted or suffered from competent or incompetent leadership. Similarly, the success stories of big private corporations in the developed world lend support to the spectacular achievement of leaders who were able to work within the framework of approved budgets and staff and yet motivate staff to achieve higher goals’

The above excerpt illustrates the significance of leadership in delivering successful outcomes. Sri Lanka has many examples which have proven that the right leadership stimulated progress and achieved expected successes. However, in recent years this has been an issue which even the President has had to lament on. There are key areas under the IMF/ World Bank assistance programs that envisage quick and methodical implementation of reform measures and development initiatives.

The lack of an institutional arrangement where a capable, experienced and proven leader assumes responsibility for the total implementation of key reform initiatives, including management of development projects, supported by a team of chosen set of administrative and professional staff is the need of the hour. It is important that the organisational structure provides for freedom of action within stipulated limits and concedes considerable authority to implement processes without reference to multiple sources. The political head of this organisational entity should ideally be the Finance Minister or the President himself who would ensure the independence of the entity to work diligently to deliver expected outputs on time and within budget.

Reviewing the book further we found some interesting thoughts and ideas that are relevant to many countries in the region, including Sri Lanka. The book covers a wide ground on the subjects of monitoring and evaluation and their relevance and significance for project development, management and evaluation. An interesting observation is ‘that in most countries of the developing world, monitoring is often conceived as collection of information and development of reporting systems, with little attention paid to using the information and reporting systems as effective management tools for controlling financial and physical performance. Management controls provide the project implementors the tools for determining whether or not the organisation is proceeding toward the objective as planned. Control has to do with making events conform to plans. It is an organic function of management which coordinates the project affairs so that project objectives are achieved’.

Control is exercised through various tools and one such tool is performance indicators which are identified at the design stage of a project as they are key variables in determining whether a project is progressing as envisaged during design. Performance indicators have to be specific, measurable, attainable, reliable and time-bound (SMART). Indicators are the quantitative or qualitative variables that provide a simple and reliable means to measure achievement, to reflect the changes connected to an intervention, or to help assess the performance of an organisation against the stated outcome. A comprehensive monitoring system postulates the need for good performance indicators, realistic target setting and collection of appropriate baseline data that would provide a comparison to gauge results during and after implementation’.

These are tools that are essential for project management and such systems have been established and are operational in Sri Lanka. There are however doubts whether the systems are being put to effective use for project management. There have been reports that lack of competent staff have often hampered the execution of appropriate strategies for implementation of a sound monitoring program. In the context of the current economic crisis it would be absolutely crucial to fine tune these tools for better collection, analysis and reporting of progress in the achievement of targets.

Evaluation

The role of evaluation in development management is being increasingly appreciated by developing countries due to continued interactions and emphasis by donors on accountability and performance management issues. There is however, a long way to go to institutionalise evaluation infrastructure in the context of emerging need to improve the quality of decision making. Some excerpts from the book under review provide interesting insights into the role and function of evaluation in improving policy formulation.’ The OECD defines evaluation as the systematic and objective assessment of an ongoing or completed project, program, or policy, including its design, implementation and results.

The aim is to determine the relevance and fulfillment of objectives, development efficiency, effectiveness, impact and sustainability. ‘An evaluation should provide information that is credible and useful, enabling the incorporation of lessons learned into the decision-making process of both recipients and donors’ Evaluation differs from monitoring-monitoring is essentially a management activity confining its concerns to the implementation cycle of program/project. Monitoring is concerned with day-to-day management aspects whereas evaluation deals with ongoing and post-project impact and effectiveness of a project. Evaluation ascertains the relevance of the project, challenges all aspects of the project design, examines performance of inputs and implementing agents against targets and may even enable redesigning or re-planning of project activities’.

‘Evaluation also uses performance indicators formulated at the design stage of a project to measure outputs, outcomes and impact. The selection of indicators is governed by the changes that are sought or anticipated. In general terms, performance indicators are included under three broad categories-economic, social and environmental’.

The above references to monitoring and evaluation are intended to highlight their relevance in the context of ongoing efforts to resuscitate the economy. It is important to ascertain whether these tools of management are currently being used to assess development operations to obtain sufficient and acceptable outcomes demanded by donors and investment partners.

The current crisis calls for the establishment of an appropriate mechanism to continuously measure results and take remedial measures, when required, to improve outcomes. For projects to succeed and improve incomes and revenues anticipated at the outset, closer supervision, monitoring and evaluation would be a prerequisite and will be demanded by donors whether it is the world Bank, IMF or ADB.

Our review of the book was intended to ascertain areas that could provide information on lessons learned to improve performance, particularly to removing the constraints to progress and economic advancement in the context of the serious economic and financial issues faced by Sri Lanka leading to bankruptcy announcement.

Though no immediate solutions could be discerned due to the nature of the subjects covered, considerable insights were gained on the long-term public sector management issues that require prompt remedial initiatives. The issues discussed herein such as removing the constraints to capacity development, improving implementation capacities of agencies, public sector performance and enhancing the approaches to management of investment projects, including greater emphasis to the establishment of a sound institutional framework are valid and require closer attention.

Overall, the need of the hour is to institutionalise the implementation machinery that could serve as a catalyst to produce results. Malaysia and Singapore introduced super implementation frameworks to achieve success in project and program delivery. Sri Lanka needs a super implementation department or ministry under the overall supervision of the President to initiate constant project reviews, alter strategies of implementation when needed, and set up effective small units under competent leaders for physical, social, environmental and procurement related aspects of implementation. Leadership is the primary component that will orchestrate delivery. Consequently, the appointment of a highly competent head/leader to organise, manage and deliver becomes crucial. If such a leader is appointed there will definitely be greater success in achieving the goals of recovery faster.

Features

Minds and Memories picturing 65 years of Sri Lankan Politics and Society

Last week I made mention of a gathering in Colombo to remember Kumar David, who passed away last October, as Comrade, Professor and Friend. The event was held on Saturday, April 5th, a day of double significance, first as the anniversary of the JVP insurrection on 5th April 1971, and now the occasion of the official welcome extended to visiting Indian Prime Narendra Modi by the still new JVP-NPP government. The venue was the Ecumenical Institute for Study and Dialogue (EISD) on Havelock Road, which has long been a forum for dialogues and discussions of topics ranging from religious ecumenism, Liberation Theology and Marxist politics. Those who gathered to remember Kumar were also drawn from many overlapping social, academic, professional and political circles that intersected Kumar’s life and work at multiple points. Temporally and collectively, the gathering spanned over six decades in the evolution of post-independence Sri Lanka – its politics, society and the economy.

Several spoke and recalled memories, and their contributions covered from what many of us have experienced as Sri Lankans from the early 1960s to the first two and a half decades of the 21st century. The task of moderating the discussion fell to Prof. Vijaya Kumar, Emeritus Professor of Chemistry at Peradeniya, who was a longtime friend of Kumar David at the university and a political comrade in the LSSP – especially in the Party’s educational and publication activities.

Vijaya Kumar recalled Kumar David’s contributions not only to Marxist politics but also to the popularization of Science that became a feature in several of KD’s weekly contributions to the Sunday Island and the Colombo Telegraph. Marshal Fernando, former and longtime Director of the EISD welcomed the participants and spoke of Kumar David’s many interactions with the Institute and his unflinching offer of support and advice to its activities. EISD’s current Director, Fr. Jayanath Panditharatne and his staff were extremely helpful.

Rohini David, Kumar’s wife of over 50 years, flew in specially for the occasion from Los Angeles and spoke glowingly of Kumar’s personal life as a husband and a father, and of his generosity for causes that he was committed to, not only political, but also, and more importantly, educational. An interesting nugget revealed by Rohini is the little known fact that Kumar David was actually baptized twice – possibly as a Roman Catholic on his father’s side, and as an Anglican on his mother’s side. Yet he grew to see an altogether different light in all of his adult life. Kumar’s father was Magistrate BGS David, and his maternal grandfather was a District Judge, James Joseph.

Kumar had an early introduction to politics as a result of his exposure to some of the political preparations for the Great Hartal of 1953. Kumar was 12 years old then, and the conduit was his step-father, Lloyd de Silva an LSSPer who was close to the Party’s frontline leaders. From a very young age, Kumar became familiar with all the leaders and intellectuals of the LSSP. Lloyd was known for his sharp wit and cutting polemics. One of my favourite lines is his characterization of Bala Tampoe as a “Lone Ranger in the Mass Movement.” Lloyd’s polemics may have rubbed on Kumar’s impressionable mind, but the more enduring effect came from Lloyd’s good collection of Marxist books that Kumar self-admittedly devoured as much as he could as a teenager and an undergraduate.

Electric Power and Politics

Early accounts of Kumar’s public persona came from Chris Ratnayake, Prof. Sivasegaram and Dr. K. Vigneswaran, all Kumar’s contemporaries at the Engineering Faculty that was then located in Colombo. From their university days in the early 1960s, until now, they have witnessed, been a part of and made their own contributions to politics and society in Sri Lanka. Chris, a former CEB and World Bank Electrical Engineer, was part of the Trotskyite LSSP nucleus in the Engineering Faculty, along with Bernard Wijedoru, Kumar David, Sivaguru Ganesan, MWW Dharmawardana, Wickramabahu Karunaratne and Chris Rodrigo. Of that group only Chris and MWW are alive now.

Chris gave an accurate outline of their political involvement as students, Kumar’s academic brilliance and his later roles as a Lecturer and Director of the CEB under the United Front Government. Chris also described Kumar’s later academic interest and professional expertise in the unbundling of power systems and opening them to the market. Even though he was a Marxist, or may be because of it, Kumar had a good understanding of the operation of the market forces in the electricity sector.

Chris also dealt at length on Sri Lanka’s divergent economic trajectories before and after 1977, and the current aftermath of the recent economic crisis. As someone who has worked with the World Bank in 81 countries and has had the experience of IMF bailout programs, Chris had both warning and advice in light of Sri Lanka’s current situation. No country, he said, has embarked on an economic growth trajectory by following standard IMF prescriptions, and he pointed out that countries like the Asian Tigers have prospered not by following the IMF programs but by charting their own pathways.

Prof. S. Sivasegaram and Dr. K. Vigneswaran graduated in 1964, one year after Kumar David, with first classes in Mechanical Engineering and Civil Engineering, respectively. Sivasegaram joined the academia like Kumar David, while Vigneswaran joined the Irrigation Department but was later drawn into the vortex of Tamil politics where he has been a voice of reason and a source for constructive alternatives. As Engineering students, they were both Federal Party supporters and were not aligned with Kumar’s left politics.

It was later at London Imperial College, Sivasegaram said, he got interested in Marxism and he credited Kumar as one of the people who introduced him to Marxism and to anti-Vietnam protests. But Kumar could not persuade Sivasegaram to be a Trotskyite. Sivasegaram has been a Maoist in politics and apart from his Engineering, he is also an accomplished poet in Tamil. Vigneswaran recalled Kumar’s political involvement as a Marxist in support of the right of self-determination of the Tamils and his accessibility to Tamil groups who were looking for support from the political left.

K. Ramathas and Lal Chandranath were students of Kumar David at Peradeniya, and both went on to become established professionals in the IT sector. Ramathas passionately recalled Kumar’s effectiveness as a teacher and described his personal debt of gratitude for helping him to get a lasting understanding of the concept and application of power system stability. This understanding has helped him deal with other systems, said Ramathas, even as he bemoaned the lack of understanding of system stability among young Engineers and their failure to properly explain and address recurrent power failures in Sri Lanka.

Left Politics without Power

The transition from Engineering to politics in the discussion was seamlessly handled by veterans of left politics, viz., Siritunga Jayasuriya, Piyal Rajakaruna and Dishan Dharmasena, and by Prof. Nirmal Dewasiri of the History Department at the University of Colombo. Siritunga, Piyal and Dishan spoke to the personal, intellectual and organizational aspects of Kumar David in the development of left politics after Kumar David, Vasudeva Nanayakkara and Bahu were no longer associated with the LSSP. Dewasiri reflected on the role of the intellectuals in left political parties and the lost to the left movement as a whole arising from the resignation or expulsion of intellectuals from left political organizations.

While Kumar David’s academic and professional pre-occupation was electric power, pursuing power for the sake of power was not the essence of his politics. That has been the case with Bahu and Sivasegaram as well. They naturally had a teaching or educational role in politics, but they shared another dimension that is universally common to Left politics. Leszek Kolakowski, the Polish Marxist who later became the most celebrated Marxist renegade, has opined that insofar as leftists are generally ahead of their times in advocating fundamental social change and promoting ideas that do not resonate with much of the population, they are unlikely to win power through electoral means.

Yet opposition politics predicated on exposing and decrying everything that is wrong with the system and projecting to change the system is fundamentally the most moral position that one can take in politics. So much so it is worth pursuing even without the prospect of power, as Hector Abhayavardhana wrote in his obituaries for LSSP leaders like NM Perera and Colvin R de Silva. By that token, the coalition politics of the 1960s could be seen as privileging a shared parliamentary path to power while dismissing as doctrinaire the insistence on a sole revolutionary path to power.

The two perspectives clashed head on and splintered the LSSP at its historic 1964 Conference. Kumar David and Lal Wijenayake were the youngest members at that conference, and the political genesis of Kumar David and others at the Engineering faculty that Chris Ratnayake outlined was essentially post-coalition politics. In later years, Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Bahu and Kumar David set about creating a left-opposition (Vama) tendency within the LSSP.

This was considered a superior alternative to breaking away from the Party that had been the experience of 1964. Kumar David may have instinctively appreciated the primacy of the overall system stability even if individual components were getting to be unstable! But their internal efforts were stalled, and they were systematically expelled from the Party one by one. Kumar David recounted these developments in the obituary he wrote for Bahu.

As I wrote last week, after 1977 and with the presidential system in place, the hitherto left political parties and organizations generally allied themselves with one or the other of the three main political alliances led by the SLFP, the SLPP and even the UNP. A cluster of them gravitated to the NPP that has been set up by the JVP under the leadership of Anura Kumara Dissanayake. Kumar David supported the new JVP/NPP initiative and was optimistic about its prospects. He wrote positively about them in his weekly columns in the Sunday Island and the Colombo Telegraph.

The Social Circles of Politics

Sometime in late 2006, Rohan Edrisinha introduced Kumar and me to Rajpal Abeynayake, who was then the Editor of the Sunday Observer, for the purpose of writing weekly columns for the Paper. Bahu was already writing for the Sunday Observer and for almost an year, Bahu, Kumar and I were Sunday Island columnists, courtesy of Rajpal Abeynayake. In 2007, Prof. Vijaya Kumar introduced us to Manik de Silva, already the doyen of Sri Lanka’s English medium editors, and Kumar and I started writing for the Sunday Island edited by Manik. It has been non-stop weekly writing a full 18 years. For a number of years, we have also been publishing modified versions of our articles in the Colombo Telegraph, the online journal edited by the inimitable Uvindu Kurukulasuriya.

Writing mainstream rekindled old friendships and created new ones. It was gratifying to see many of them show up at the celebration of life for Kumar. That included Rajpal Abeynayake, Bunchy Rahuman, Gamini Kulatunga, Ranjith Galappatti, Tissa Jayatilaka, NG (Tanky) Wickremeratne, and Manik de Silva. Vijaya Chandrasoma, who unfortunately could not attend the meeting, was particularly supportive of the event along with Tanky and Ramathas. Tissa and Manik spoke at the event and shared their memories of Kumar.

Dr. Santhushya Fernando of the Colombo Medical Faculty provided organizational support and created two superb video montages of Kumar’s life in pictures to background theme songs by Nat King Cole and Frank Sinatra. Manoj Rathnayake produced a Video Recording of the event.

In a quirky coincidence, five of those who attended the event, viz. Manik de Silva, Vijaya Kumar, Chris Ratnayake, S. Sivasegaram and K. Vigneswaran were all classmates at Royal College. On a personal note, I have been associated with every one of them in one way or another. Chris and I were also Engineers at the Hantana Housing Development in the early 1980s, for which the late Suren Wickremesinghe and his wife Tanya were the Architects. And Suren was in the same Royal College class as the other five mentioned here.

In the last article he wrote before his passing, Kumar David congratulated Anura Kumara Dissanayake for his magnificent political achievement and expressed cautious optimism for the prospects under an NPP government. Many in the new government followed Kumar David’s articles and opinions and were keen to participate in the celebration of life that was organized for him. That was not going to be possible anyway with the visit of Prime Minister Modi falling on the same day. Even so, Prof. Sunil Servi, Minister of Buddha Sasana, and Religious and Cultural Affairs, was graciously present at the event and expressed his appreciation of Kumar David’s contributions to Sri Lankan politics and society.

by Rajan Philips

Features

53 Years of HARTI- Looking Back and Looking Ahead

C. Narayanasuwami, the first Director of the then Agrarian Research and Training Institute (ARTI).

I am delighted to be associated with the fifty third anniversary celebrations of HARTI. I cherish pleasant memories of the relentless efforts made as the First Director to establish, incorporate, develop, direct, and manage a nascent institute in the 1970s amidst many challenges. The seven-year period as Director remains as the most formidable and rewarding period in my career as a development professional. I have been fortunate to have had a continuing relationship with HARTI over the last five decades. It is rarely that one who played a significant role in the establishment and growth of an institution gets an opportunity to maintain the links throughout his lifetime and provide messages on the completion of its fifth (I was still the director then), the 15th, 50th and 53rd anniversaries.

I had occasion also to acknowledge the contribution of the Institute on its 46th year when I released my book, ‘Managing Development: People, Policies and Institutions’ using HARTI auditorium and facilities, with the able support of the then director and staff who made the event memorable. The book contains a special chapter on HARTI.

On HARTI’s 15th anniversary I was called upon to offer some thoughts on the Institute’s future operations. The following were some of my observations then, “ARTI has graduated from its stage of infancy to adolescence….Looking back it gives me great satisfaction to observe the vast strides it has made in developing itself into a dynamic multidisciplinary research institution with a complement of qualified and trained staff. The significant progress achieved in new areas such as marketing and food policy, data processing, statistical consultancies, information dissemination and irrigation management, highlights the relevance and validity of the scope and objectives originally conceived and implemented”.

It may be prudent to review whether the recommendations contained in that message, specifically (a) the preparation of a catalogue of research findings accepted for implementation partially or fully during policy formulation, (b) the relevance and usefulness of information services and market research activities in enhancing farmer income, and (c) the extent to which the concept of interdisciplinary research- a judicious blend of socio-economic and technical research considered vital for problem-oriented studies- was applied to seek solutions to problems in the agricultural sector.

The thoughts expressed on the 15th anniversary also encompassed some significant management concerns, specifically, the need to study the institutional capabilities of implementing agencies, including the ‘human factor’ that influenced development, and a critical review of leadership patterns, management styles, motivational aspects, and behavioural and attitudinal factors that were considered vital to improve performance of agrarian enterprises.

A review of HARTI’s current operational processes confirm that farmer-based and policy-based studies are given greater attention, as for example, providing market information service for the benefit of producers, and undertaking credit, microfinance, and marketing studies to support policy changes.

The changes introduced over the years which modified the original discipline-based research units into more functional divisions such as agricultural policy and project evaluation division, environmental and water resources management division, and agricultural resource management division, clearly signified the growing importance attached to functional, action-oriented research in preference to the originally conceived narrowly focused discipline-based research activities.

HARTI has firmly established its place as a centre of excellence in socio-economic research and training with a mature staff base. It is pertinent at this juncture to determine whether the progress of HARTI’s operations was consistently and uniformly assessed as successful over the last five decades.

Anecdotal evidence and transient observations suggest that there were ups and downs in performance standards over the last couple of decades due to a variety of factors, not excluding political and administrative interventions, that downplayed the significance of socio-economic research. The success of HARTI’s operations, including the impact of policy-based studies, should be judged on the basis of improved legislation to establish a more structured socio-economic policy framework for agrarian development.

Looking Ahead

Fifty-three years in the life of an institution is substantial and significant enough to review, reflect and evaluate successes and shortcomings. Agrarian landscapes have changed over the last few decades and national and global trends in agriculture have seen radical transformation. Under these circumstances, such a review and reflection would provide the basis for improving organisational structures for agricultural institutions such as the Paddy Marketing Board, development of well-conceived food security plans, and above all, carefully orchestrated interventions to improve farmer income.

New opportunities have arisen consequent to the recent changes in the political horizon which further validates the role of HARTI. HARTI was born at a time when Land Reform and Agricultural Productivity were given pride of place in the development programs of the then government. The Paddy Lands Act provided for the emancipation of the farming community but recent events have proven that the implementation of the Paddy Lands Act has to be re-looked at in the context of agricultural marketing, agricultural productivity and income generation for the farming community.

Farmers have been at the mercy of millers and the price of paddy has been manipulated by an oligopoly of millers. This needs change and greater flexibility must be exercised to fix a guaranteed scale of prices that adjust to varying market situations, and provide adequate storage and milling facilities to ensure that there is no price manipulation. It is time that the Paddy Lands Act is amended to provide for greater flexibility in the provision of milling, storage and marketing services.

The need for restructuring small and medium scale enterprises (SMEs) recently announced by the government warrants greater inputs from HARTI to study the structure, institutional impediments and managerial constraints that inflict heavy damages leading to losses in profitability and organisational efficiency of SMEs.

Similarly, HARTI should look at the operational efficiency of the cooperative societies and assess the inputs required to make them more viable agrarian institutions at the rural level. A compact research exercise could unearth inefficiencies that require remedial intervention.

With heightened priority accorded to poverty alleviation and rural development by the current government, HARTI should be in the forefront to initiate case studies on a country wide platform, perhaps selecting areas on a zonal basis, to determine applicable modes of intervention that would help alleviate poverty.

The objective should be to work with implementing line agencies to identify structural and institutional weaknesses that hamper implementation of poverty reduction and rural development policies and programs.

The role played in disseminating marketing information has had considerable success in keeping the farming community informed of pricing structures. This should be further expanded to identify simple agricultural marketing practices that contribute to better pricing and income distribution.

HARTI should consider setting up a small management unit to provide inputs for management of small-scale agrarian enterprises, including the setting up of monitoring and evaluation programs, to regularly monitor and evaluate implementation performance and provide advisory support.

Research and training must get high level endorsement

to ensure that agrarian policies and programs constitute integral components of the agricultural development framework. This would necessitate a role for HARTI in central planning bodies to propose, consider and align research priorities in line with critical agricultural needs.

There is a felt need to establish links with universities and co-opt university staff to play a role in HARTI research and training activities-this was done during the initial seven-year period. These linkages would help HARTI to undertake evaluative studies jointly to assess impacts of agrarian/agricultural projects and disseminate lessons learned for improving the planning and execution of future projects in the different sectors.

In the overall analysis, the usefulness of HARTI remains in articulating that research and analysis are crucial to the success of implementation of agrarian policies and programs.

In conclusion, let us congratulate the architects and the dynamic management teams and staff that supported the remarkable growth of HARTI which today looks forward to injecting greater dynamism to build a robust institution that would gear itself to meeting the challenges of a new era of diversified and self-reliant agrarian society. As the first director of the Institute, it is my wish that it should grow from strength to strength to maintain its objectivity and produce evidence-based studies that would help toward better policies and implementation structures for rural transformation.

Features

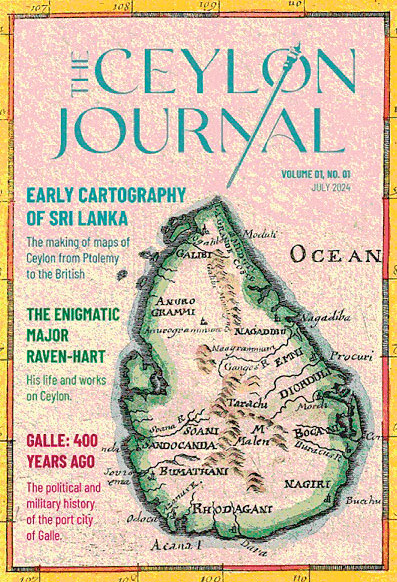

Keynote Speech at the Launch of The Ceylon Journal, by Rohan Pethiyagoda

“How Rubber Shaped our Political Philosophy”

The Ceylon Journal was launched last August. Its first issue is already out of print. Only a handful of the second issue covering new perspectives of history, art, law, politics, folklore, and many other facets of Sri Lanka is available. To reserve your very own copy priced Rs. 2000 call on 0725830728.

Congratulations, Avishka [Senewiratne]. I am so proud of what you have done. Especially, Ladies and Gentlemen, to see and hear all of us stand up and actually sing the National Anthem was such a pleasure. Too often on occasions like this, the anthem is played, and no one sings. And we sang so beautifully this evening that it brought tears to my eyes. It is not often we get to think patriotic thoughts in Sri Lanka nowadays: this evening was a refreshing exception.

I’m never very sure what to say on an occasion like this, in which we celebrate history, especially given that I am a scientist and not a historian. It poses something of a challenge for me. Although we are often told that we must study history because it repeats itself, I don’t believe it ever does. But history certainly informs us: articles such as those in The Ceylon Journal, of which I read an advance copy, help us understand the context of our past and how it explains our present.

I want to take an example and explain what I am on about. I’m going to talk about rubber. Yes rubber, as in ‘eraser’, and how it crafted our national political identity, helping, even now seven decades later, to make ‘capitalism’ a pejorative.

As I think you know already, rubber came into general use in the middle of the 19th century. Charles Macintosh invented the raincoat in 1824 by placing a thin sheet of rubber between two sheets of fabric and pressing them together. That invention transformed many things, not least warfare. Just think of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in the winter of 1812. His troops did that without any kind of waterproof clothing. Some 200,000 of them perished, not from bullets but from hypothermia. Waterproof raincoats could have saved thousands of lives. Not long after rubber came to be used for waterproofing, we saw the first undersea telegraph cable connecting Europe to North America being laid in the 1850s. When the American civil war broke out in 1860, demand for rubber increased yet further: the troops needed raincoats and other items made from this miracle material.

At that time rubber, used to be collected from the wild in the province of Pará in Northern Brazil, across which the Amazon drains into the Atlantic. In 1866, steamers began plying thousands of kilometres upriver, to return with cargoes of rubber harvested from the rainforest. Soon, the wild trees were being tapped to exhaustion and the sustainability of supply became doubtful.

Meanwhile, England was at the zenith of its colonial power, and colonial strategists thought rather like corporate strategists do today. The director of the Kew Gardens at the time, Joseph Hooker, felt there might be one day be a greater potential for rubber. He decided to look into the possibility of cultivating the rubber tree, Hevea brasiliensis, in Britain’s Asian colonies. So, he dispatched a young man called Henry Wickham to the Amazon to try to secure some seeds. In 1876, Wickham returned to Kew with 70,000 rubber seeds. These were planted out in hothouses in Kew and by the end of that year, almost 2000 of them had germinated.

These were dispatched to Ceylon, only a few weeks’ voyage away now, thanks to steamships and the Suez Canal. The director of the Peradeniya Botanic Garden at the time was George Henry Kendrick Thwaites, a brilliant systematic botanist and horticulturalist. Thwaites received the seedlings and had to decide where to plant them. He read the available literature—remember, this was 1876: there was no internet—and managed to piece together a model of the climatic conditions in the region of the Amazonian rainforest to which rubber was native. He decided that the plants would need an elevation of less than 300 metres and a minimum annual rainfall of at least 2000mm. In other words, the most suitable region for rubber would be an arc about 30 kilometres wide, extending roughly from Ambalangoda to Matale. Despite his never having seen a rubber plant until then, astonishingly, he got it exactly right.

Thwaites settled on a site in the middle of the arc, at Henarathgoda near Gampaha. That became the world’s first rubber nursery: the first successful cultivation of this tree outside Brazil. The trees grew well and, eight years later, came into seed. Henry Trimen, Thwaites’ successor, used the seeds to establish an experimental plantation near Polgahawela and also shared seeds with the Singapore Botanic Garden. Those would later become the foundation of the great Malaysian rubber industry.

But up to that time, Sri Lanka’s rubber plantation remained a solution looking for a problem. Then, in 1888, the problem arrived, and from a completely unexpected quarter: John Dunlop invented the pneumatic tire. Soon, bicycles came to be fitted with air-filled tires, followed by motorcars. In 1900, the US produced just 5,000 motorcars; by 1915, production had risen to half a million. The great rubber boom had begun.

Meanwhile, the colonial administration in Ceylon had invited investors to buy land and start cultivating rubber to feed the growing international demand. But by the early 1890s, three unusual things had happened. First, with the collapse of the coffee industry in the mid-1870s, many British investors had been bankrupted. Those who survived had to divert all their available capital into transitioning their failing coffee plantations into tea. They were understandably averse to risk. As a result, the British showed little interest in this strange tree called rubber that had been bought from Brazil.

Second, a native Sri Lankan middle class had by then emerged. The Colebrooke-Cameron reforms had led to the establishment of the Royal academy, later Royal College, by 1835. Other great schools followed in quick succession. From the middle of the 19th century, it was possible for Sri Lankans to get an education and get employment in government service, become professionals, doctors, lawyers, engineers, civil servants, clerks, and so on. And so, by the 1890s, a solid native middle class had emerged. The feature that defines a middle class, of course, is savings, and these savings now came to be translated into the capital that founded the rubber industry.

Third, the British had by then established a rail and road network and created the legal and commercial institutions for managing credit and doing business—institutions like banks, financial services, contract law and laws that regulated bankruptcy. They had made the rules, but by now, Sri Lankans had learned to play the game. And so, it came to be that Sri Lankans came to own a substantial part of the rubber-plantation industry very early in the game. By 1911, almost 200,000 acres of rubber had been planted and world demand was growing exponentially.

In just one generation, investors in rubber were reaping eye-watering returns that in today’s money would equate to Rs 3.6 million per acre per year. It was these people who, together with the coconut barons, came to own the grand mansions that adorn the poshest roads in Cinnamon Gardens: Ward Place, Rosmead Place, Barnes Place, Horton Place, and so on. There was an astonishingly rapid creation of indigenous wealth. By 1911, the tonnage at shipping calling in Sri Lankan ports—Colombo and Trincomalee—exceeded nine million tons, making them collectively the third busiest in the British Empire and the seventh busiest in the world. By comparison, the busiest port in Europe is now Rotterdam, which ranks tenth in the world.

We often blame politicians for things that go wrong in our country and God knows they are responsible for most of it. But unfortunately for us, the first six years of independence, from 1948 to 1954, were really unlucky years for Sri Lanka. As if successive failed monsoons and falling rice crops weren’t bad enough, along came the Korean war. In the meantime, the Sri Lankan people had got used to the idea of food rations during the war and they wanted rations to be continued as free handouts. Those demands climaxed in the ‘Hartal’ of 1953, a general strike demanding something for nothing. Politicians were being forced to keep the promises they had made when before independence, that they would deliver greater prosperity than under the British.

We often blame politicians for things that go wrong in our country and God knows they are responsible for most of it. But unfortunately for us, the first six years of independence, from 1948 to 1954, were really unlucky years for Sri Lanka. As if successive failed monsoons and falling rice crops weren’t bad enough, along came the Korean war. In the meantime, the Sri Lankan people had got used to the idea of food rations during the war and they wanted rations to be continued as free handouts. Those demands climaxed in the ‘Hartal’ of 1953, a general strike demanding something for nothing. Politicians were being forced to keep the promises they had made when before independence, that they would deliver greater prosperity than under the British.

So, by 1949, D. S. Senanayake was forced to devalue the rupee, leading to rapid price inflation. Thankfully we didn’t have significant foreign debt then, or we might have had to declare insolvency much earlier than we finally did, in 2022. And then, because of failing paddy harvests, we were forced to buy rice

from China, which was in turn buying our rubber. But as luck would have it, China entered the Korean war, causing the UN, at the behest of the US, to embargo rubber exports to China.

This placed the D. S. Senanayake and John Kotelawala governments in an impossible predicament. There was a rice shortage; people were demanding free rice, and without rubber exports, there was no foreign exchange with which to buy rice. Kotelawala flew to Washington, D.C., to meet with President Eisenhower and plead for either an exemption from the embargo or else, for the US to buy our rubber. Despite Sri Lanka having provided rubber to the Allies at concessionary prices during the war and having supported the Allies, Eisenhower refused. British and American memories were short indeed. In India, Mahatma Gandhi and the Congress Party had chosen the moment, in August 1942 when Japan invaded Southeast Asia and were poised to invade Bengal, to demand that the British quit India, threatening in the alternative that they would throw their lot in with the Japanese. The Sri Lankan government, by contrast, had stood solidly by the Allies. But now, those same allies stabbed the fledgling nation in the chest. Gratitude, it seemed, was a concept alien to the West.

In these circumstances, Sri Lanka had no choice but to break the UN embargo and enter into a rice-for-rubber barter agreement with China. This resulted not only in the US suspending aid and the supply of agricultural chemicals to Sri Lanka, but also invoking the Battle Act and placing restrictions on US and UK ships calling at the island’s ports.

Understandably, by 1948, Sri Lankans entertained a strong disdain for colonialism. With the Cold War now under way, the USSR and China did all they could to split countries like Sri Lana away not just from their erstwhile colonial masters but also the capitalist system. If any doubt persisted in the minds of Sri Lankan politicians, Western sanctions put an end to that. The country fell into the warm embrace of the communist powers. China and the USSR were quick to fill the void left by the West, and especially in the 1950s, there was good reason to believe that the communist system was working. The Soviet economy was seeing unprecedented growth, and that decade saw them producing hydrogen bombs and putting the first satellite, dog and man in space.

As a consequence of the West’s perfidy in the early 1950s, ‘Capitalism’ continues to have pejorative connotations in Sri Lanka to this day. And it resulted in us becoming more insular, more inward looking, and anxious to assert our nationalism even when it cost us dearly.

Soon, we abolished the use of English, and we nationalized Western oil companies and the plantations. None of these things did us the slightest bit of good. We even changed the name of the country in English from Ceylon to Sri Lanka. Most countries in the world have an international name in addition to the name they call themselves. Sri Lanka had been ‘Lanka’ in Sinhala throughout the colonial period, even as its name had been Ceylon in English. The Japanese don’t call themselves Japan in their own language, neither do the Germans call themselves Germany. These are international names for Nihon and Deutschland, just like Baharat or Hindustan is what Indians call India. But we insisted that little Sri Lanka will assert itself and insist what the world would call us, the classic symptom of a massive inferiority complex. While countries like Singapore built on the brand value of their colonial names, we erased ours from the books. Now, no one knows where Ceylon tea or Ceylon cinnamon comes from.

Singapore is itself a British name: it should be Sinha Pura, the Lion City, a Sanskrit name. But Singapore values its bottom line more than its commitment to terminological exactitude. Even the name of its first British governor, Sir Stamford Raffles, has become a valued national brand. But here in Sri Lanka, rather than build on our colonial heritage, not the least liberal values the British engendered in us, together with democracy and a moderately regulated economy, we have chosen to deny it and seek to expunge it from our memory. We rejected the good values of the West along with the bad: like courtesy, queuing, and the idea that corruption is wrong.

We have stopped fighting for the dignity of our land, and I hope that as you read the articles in The Ceylon Journal that are published in the future, we will be reminded time and time again of the beautiful heritage of our country and how we can once again find it in ourselves to be proud of this wonderful land.

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoSuspect injured in police shooting hospitalised

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoRobbers and Wreckers

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoSri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part III

-

Midweek Review6 days ago

Midweek Review6 days agoInequality is killing the Middle Class

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoSanjiv Hulugalle appointed CEO and General Manager of Cinnamon Life at City of Dreams Sri Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoNational Anti-Corruption Action Plan launched with focus on economic recovery

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoLiberation Day tariffs chaos could cause permanent damage to US economy, amid global tensions

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoIChemC signs MoU with KIIT, India