Features

Selling Oil, motor racing and moving from Shell to Reckitt and Colman

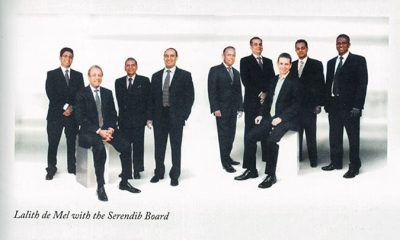

Excerpted from the memoirs of

Lalith de Mel

His first real job was with the Shell Company of Ceylon Ltd. Which her joined at age 22. The Research Economist role at the Coconut Research Institute was almost a continuation of life at Cambridge. Academic research at one’s own pace was close to preparing a piece of work for the supervisor.

Shell was a proper job. He had a boss, and he had to accomplish whatever his boss wanted him to do in an industry and in activity that was far removed from Economics. It was new territory, marketing petroleum products. It was his first encounter with petroleum and his first encounter with marketing, but he settled easily into the world of commerce.

His first role at Shell was working directly for the Head of Marketing as his Personal Assistant. He was an experienced petroleum man and a rather unfriendly Egyptian national. His core role for Lalith was having him prepare feasibility studies on building new filling stations.

Shell worked a half day on Saturdays, and Mike Khoury (that was his name) would give him an assignment around 11 a.m. and insist that he gets the report the same day. He did this regularly and justified it by saying that it was only on Saturday afternoons that he had the time to study investment projects. Lalith grudgingly says that this was probably true.

After his stint as a PA he was given responsibility for marketing kerosene and reporting to an Iraqi national. The man was happy to not exert himself unduly and probe the rural markets and to leave it all to Lalith. He was pleased that as a 22-year-old he was virtually responsible for marketing kerosene, which was perceived as a product with good growth potential. It was the main source of lighting in rural areas and the task was to persuade housewives to move from firewood to kerosene for cooking.

He enjoyed the opportunity of traveling all over the rural areas. It was perhaps this understanding of rural areas that has triggered his firm belief in the need to develop rural areas, on which theme he has written many articles.

From kerosene, he became a part of the Retail Marketing team. That was the engine room that drove sales of Shell products. Shell was one of the key retailers of petroleum products worldwide. The main competitors globally were equally big boys. Market share varied. The way Shell International ensured consistency in approach across the world was by having detailed process manuals for all parts of the marketing mix. The local companies had to develop their campaigns within the lines set by the process manuals. It was a wonderful course in structured marketing. He says it was like doing a marketing degree and freely admits that he learned his marketing at Shell.

After a few years, he was moved to the Finance Division. He had twin roles. In addition to carrying out a normal accounting function, he worked in the special unit created to study the options for formulating claims for compensation for assets that were taken over by the Government when Shell and the other oil companies were partly nationalized. He quickly became head of this unit and his last role was in putting together the claims for compensation on the agreed format, signing on behalf of Shell and submitting the claims to the Government.

Shell was keen that he should continue his lectures at Aquinas, and he continued to teach students studying for the BSc London University Economics degree in the evenings.

Outside work, Shell was a fun place. It had an excellent sports ground. He got into the cricket team that was in the A division of the Mercantile league. He also played badminton and hockey in the inter-firm tournaments. Shell took a keen interest in motor racing. The objective was to get the top drivers to use Shell petrol and Shell oil. Dudley Perera, a very Senior Manager at the time, was the link man between Shell and motor racing and Lalith became his assistant.

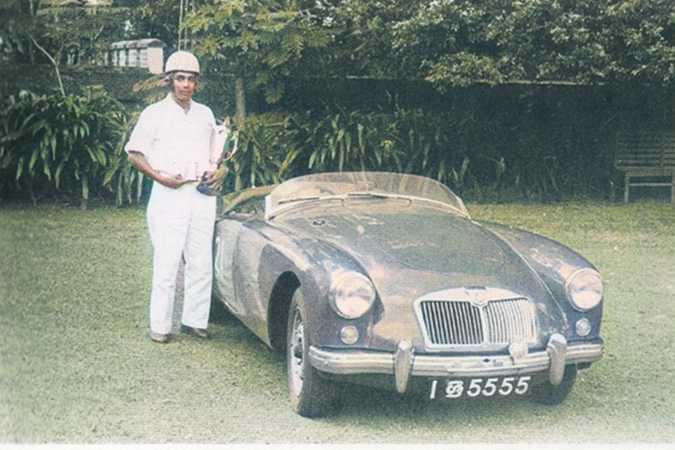

The atmosphere at motor race meets, the roar from the cars, the smell of burning oil and the vibes from screeching tyres got to him and he started motor racing. He drove a red MGA with the distinctive number plate I SRI 5555. He raced for many years and had his share of wins both at Katukurunda and the Mahagastota Hill Climb in Nuwara Eliya. In one event at Katukurunda, he raced with Upali Wijewardene, his Cambridge University friend and subsequent famous entrepreneur, and Asoka Gopallawa, the son of the Governor General, all driving MGAs.

How Shell plans management succession

“After five years at Shell, I felt the urge to move on. There was uncertainty about the future, with partial nationalization of the petroleum industry. The exciting future appeared to be in the new foreign investments to set up the manufacturing industry.

When I sent in my resignation, I was summoned by the General Manager, a Dutchman named Jan Van Reeven. He did not want me to go as they had identified me as a potential International General Manager. I probably had a bemused expression on my face and so Van Reeven said, `Let me explain.’ He said that Shell had over 100 operating companies around the world and they had 100 General Managers, some would move to other companies, some would get fired and the rest would eventually retire at some stage in the future. So he said it was a continuous process in Shell companies to identify potential future General Managers and to develop suitable career paths for them that would eventually lead to a General Manager post in the future.

The process, he explained, was for operating Shell companies to seek and recruit outstanding persons as management trainees from time to time. The new trainee’s first job is to work for one of the directors as a Personal Assistant. At the end of this period, an early call is made as to whether the person is a potential future GM. If the answer is yes, the trainee is given a challenging career path and reassessed at the end of each year.

`As your preferred path was Marketing, you were given various marketing roles,’ Van Reeven explained. After three years the Shell approach was to test the trainee in a different discipline. “That’s why you were transferred to Finance as an Accountant.’ He then said: ‘After five years, we were convinced you would be a future GM and our development plan is to transfer you to the international pool as an employee of Shell International and transfer you to a Shell Company overseas.’

I was having a great social life in Colombo and had no desire to go and work abroad. 1 thanked him for the excellent training I had at Shell and said all the appropriate nice things about Shell and Van Reeven and then said I was firmly committed to pursuing a Marketing career in a consumer goods company. He was very gracious and wished me well and as I got up to leave he said, ‘Someone I know is setting up a multinational manufacturing company and he wants a marketing man; would you like to meet him?’ I said yes and he sent me to meet Alex Alexander, the Managing Director of Reckitt & Colman of Ceylon, who was setting up the business. He offered me the Marketing Manager role. I accepted, and that was the start of my journey with Reckitt & Colman.”

He was marketing manager of Reckitts at age 27 and a director of that company at 29-years.

Shell always had a big advertising budget. Their agency was Grants, then headed by Reggie Candappa and his assistant was Anandatissa de Alwis, who later became Minister of State and the Speaker. Later on in life he started his own agency, De Alwis Advertising. Lalith said: “They both became good lifelong friends. I signed them on and they became our advertising agents at Reckitt & Colman. They deserve a good part of the credit for the excellent sales performance of the string of brands we launched.”

The first Marketing Manager of Reckitt & Colman of Ceylon was Michael Morris. He had been with the Indian business for a few years and came to help to set up the new business in Sri Lanka. He was in Sri Lanka for a relatively short period; he decided to go back to the UK as his wife was a doctor and wanted to go back into medical practice. This created the vacancy for which he was recruited. Morris later became a Member of the British Parliament and Deputy Speaker and was then ennobled to become Lord Naseby. He was recently in the news about war crimes in Sri Lanka. He continues to be a good friend.

Two Englishmen had been sent to start the business, Alex Alexander as Managing Director and Peter Crisp as Factory Manager. All the hard work was at the manufacturing end. Disprin was being manufactured for the first time outside the UK. A whole host of previously imported products were progressively locally manufactured.

The excitement of getting a job as a Marketing Manager of consumer products in a multinational company was short-lived. He soon felt it was a well-paid non-job with nothing to do by afternoon. The Reckitt’s products were distributed by E.B. Creasy & Co. and the Goya range by Lalvani Brothers; the advertisements were sent from the UK. All the advertisements were ones used by the group in the UK. All he had to do was send them to the advertising agency.

After a few months he assessed the scene and made his move. It was brave, reckless or foolish. He had never marketed any consumer products, knew nothing about the Pettah wholesale market which controlled 50% of sales and had never managed a sales force. He was good with numbers and knew how to put together convincing project proposals (learnt the hard way at Shell).

He formulated a proposal to terminate the distribution agreements, to set up his own marketing office and to recruit a sales force, a product manager and an advertising manager. In his proposal, he demonstrated that the commissions paid to the two distributors would more than cover the cost and in fact make a significant contribution to profits. The MD Alexander was impressed with the proposal and bought into the idea. He had just asked one question: “Are you sure you can do it?” When Lalith said “yes,” Alexander had said, “Okay, go and do it.”

He did not quite know how he was going to do it. There were many things he had not done before but he was certain that he could do them. As subsequent events will show, this was a trait he carried right through his life. He persuaded Terrence de Silva who had worked for him at Shell to join him as the Manager for everything – HR, admin, credit control, managing the fleet of vans, etc. Terrence was with him as a part of the team until he left for England. Terrence was the engine room of the Marketing division and kept everything running smoothly, whilst he launched and developed a great basket of products.

They had an amazing array of products, such as Disprin, Dettol, Brasso, Silvo, Robin Blue, Harpic, Mansion polish, Cobra shoe polish and the Goya range of fragrance products such as perfumes, colognes, talc and soap. One by one they were rolled on to the market and it was a great challenging time for him.

Fortunately it all worked out well, the sales grew, there were no bad debts, which was always a risk with the Pettah wholesale market, the profits grew and the business was highly successful and profitable. The overseas investors were pleased.

Basil Reckitt’s visit

There is a story that must be told. Basil Reckitt, the Chairman of Reckitt & Colman UK, came for the formal opening, which was also attended by Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, as it was the first major foreign investment in Sri Lanka during her tenure as the Prime Minister.

They were seated next to each other and chatting and she asked Basil Reckitt whether there was anything that she could do and he said, “Please could we have a telephone?” Those were the days when it was impossible to get a telephone. When Lalith became the Chairman of Sri Lanka Telecom later on, his objective was to make sure that anybody who wanted a telephone would get one within a week and by the time he left his role this objective had been achieved.

Marriage

In 1966, whilst he was busy building the business, he also got married. His wife was then an undergraduate at the University of Colombo and she had to continue her studies to complete her degree. After she graduated, she started working in the university itself Since she was studying, they did not have a much of social life in the evenings, so he thought it would be useful to do some studying himself and he started studying Accountancy. He completed the intermediate exams of Cost and Works Accountants, the precursor of CIMA, and also did the exams to become an Associate of the Institute of Book Keepers. When his wife graduated and was no longer poring over books in the evening, he stopped his studies. However what he had learned proved to be very helpful as it helped him to develop a good understanding of finance and accounting.

Managing Directors

Alex Alexander moved on to another part of the Group and was followed by Mark Foster, who was also a Cambridge graduate. When Mark moved on, he was followed by Greg Courtier, who became his third British boss. He did not resent this as that was the style back then, where all foreign firms had a foreigner as the Managing Director.

He was asked to say something in his own words about his key achievements and his relationship with his foreign bosses during this period. Multinationals controlled their businesses from Head Office. The local Managing Director reported to a Regional Director at Corporate Headquarters. There were very specific guidelines on what required approval from HQ

“All advertisements were sent from the UK. For the local language press we had to translate the English ads. After my spell at Shell, I appreciated that multinationals wanted to preserve the brand footprint and have the same consistent message all over the world. The challenge was to wriggle some freedom within this constraint in order to create better advertising that was more relevant in the context of the local market. After a long exchange of correspondence, I succeeded in getting approval to create our own ads.

I had to stay within the parameters of the global branding footprint but was given freedom on how to convey this in local media. We were probably the first Reckit’s market in the Commonwealth to win

this concession. I also got approval to shift the positioning of Dettol from solely a treatment for cuts and wounds to a personal care product that prevented infection. I pursued this right through my career and created a mega global brand in developing countries that is still growing. Dettol is

amazing marketing story as nobody has seen germs or seen Dettol kill germs, but were made to believe that it did provide protection from germs.Both Mark Foster and Greg Courtier were marketers, but they knew nothing about how to market and advertise products in Ceylon. They thought it prudent not to interfere with me and I had the freedom to operate in effect without a boss in the Colombo office whilst the MD worked out of the factory and office at Ratmalana. The challenge in a multinational is getting this freedom.

The UK office was pleased with the results and naturally the MD got the credit for the good sales and profits growth. I made no claims for any credit from our lords and masters in the UK for the good results. When the Head Office staff visited the business, I made it a point to say as many times as possible how much I enjoyed working with Mark/ Greg and said I greatly valued their guidance. It was true I enjoyed working with them because they did not interfere. As for guidance it was not true, and they were not really able to provide any meaningful guidance.

But strategically it was a good thing to say, so this led to a good partnership with the Managing Director. Not getting the credit and warm congratulations from the parent company was a small price to pay for having complete freedom. I steered well clear of the pitfall of trying to get plaudits for the company performance from the overseas owners and getting into a competition for praise with the boss and thereby having a not-so-congenial relationship with him.

I had a gut feeling that payback time would come. They were possibly slightly embarrassed to take the credit for my sales and profits results and had to do something to acknowledge my contribution. They recommended that I be made a Director of the Ceylon Company, which was a public quoted company.

I was pleased and content. That was as far as one’s aspirations went in those days, to become a director of a local multinational company. There was no ambition to go any further, because less foreign firms were likely to always have a foreigner as the head of their business.

The Government formed a new company named Consolidated Exports and it came to be called Consolexpo. This was a joint public sector-private sector partnership to generate and support the growth of exports. I was flattered and pleased when I was invited to join the Board. This was my first experience with the Government sector. It was also my first Board appointment outside Reckitt & Colman, so I count this as one of my achievements during this period.

Then one day a visiting director from the parent company called me in for a chat. He said they had been following my progress and were pleased with what they saw. He said almost casually that I might have the chance of being the first Sri Lankan Managing Director, but added in the same breath that I would have to prove myself in another market. I impulsively asked whether I could be sent to Australia. Half my vintage Josephian rugger team and all my Burgher school friends had migrated to Melbourne. I thought if I had a spell in Australia I could have a whale of a time with my old buddies.

The visiting Director said, ‘We will let you know in due course’ and eventually they told me that they had decided I should go and work in Brazil as a member of the management team of that company. That was their biggest business in South America and it was a huge market. Brazil was five times the size of India.

Features

Ranking public services with AI — A roadmap to reviving institutions like SriLankan Airlines

Efficacy measures an organisation’s capacity to achieve its mission and intended outcomes under planned or optimal conditions. It differs from efficiency, which focuses on achieving objectives with minimal resources, and effectiveness, which evaluates results in real-world conditions. Today, modern AI tools, using publicly available data, enable objective assessment of the efficacy of Sri Lanka’s government institutions.

Among key public bodies, the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka emerges as the most efficacious, outperforming the Department of Inland Revenue, Sri Lanka Customs, the Election Commission, and Parliament. In the financial and regulatory sector, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) ranks highest, ahead of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Public Utilities Commission, the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission, the Insurance Regulatory Commission, and the Sri Lanka Standards Institution.

Among state-owned enterprises, the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) leads in efficacy, followed by Bank of Ceylon and People’s Bank. Other institutions assessed included the State Pharmaceuticals Corporation, the National Water Supply and Drainage Board, the Ceylon Electricity Board, the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, and the Sri Lanka Transport Board. At the lower end of the spectrum were Lanka Sathosa and Sri Lankan Airlines, highlighting a critical challenge for the national economy.

Sri Lankan Airlines, consistently ranked at the bottom, has long been a financial drain. Despite successive governments’ reform attempts, sustainable solutions remain elusive.

Globally, the most profitable airlines operate as highly integrated, technology-enabled ecosystems rather than as fragmented departments. Operations, finance, fleet management, route planning, engineering, marketing, and customer service are closely coordinated, sharing real-time data to maximise efficiency, safety, and profitability.

The challenge for Sri Lankan Airlines is structural. Its operations are fragmented, overly hierarchical, and poorly aligned. Simply replacing the CEO or senior leadership will not address these deep-seated weaknesses. What the airline needs is a cohesive, integrated organisational ecosystem that leverages technology for cross-functional planning and real-time decision-making.

The government must urgently consider restructuring Sri Lankan Airlines to encourage:

=Joint planning across operational divisions

=Data-driven, evidence-based decision-making

=Continuous cross-functional consultation

=Collaborative strategic decisions on route rationalisation, fleet renewal, partnerships, and cost management, rather than exclusive top-down mandates

Sustainable reform requires systemic change. Without modernised organisational structures, stronger accountability, and aligned incentives across divisions, financial recovery will remain out of reach. An integrated, performance-oriented model offers the most realistic path to operational efficiency and long-term viability.

Reforming loss-making institutions like Sri Lankan Airlines is not merely a matter of leadership change — it is a structural overhaul essential to ensuring these entities contribute productively to the national economy rather than remain perpetual burdens.

By Chula Goonasekera – Citizen Analyst

Features

Why Pi Day?

International Day of Mathematics falls tomorrow

The approximate value of Pi (π) is 3.14 in mathematics. Therefore, the day 14 March is celebrated as the Pi Day. In 2019, UNESCO proclaimed 14 March as the International Day of Mathematics.

Ancient Babylonians and Egyptians figured out that the circumference of a circle is slightly more than three times its diameter. But they could not come up with an exact value for this ratio although they knew that it is a constant. This constant was later named as π which is a letter in the Greek alphabet.

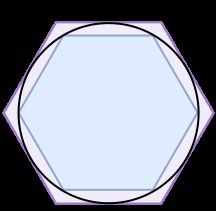

It was the Greek mathematician Archimedes (250 BC) who was able to find an upper bound and a lower bound for this constant. He drew a circle of diameter one unit and drew hexagons inside and outside the circle such that the sides of each hexagon touch the sides of the circle. In mathematics the circle passing through all vertices of a polygon is called a ‘circumcircle’ and the largest circle that fits inside a polygon tangent to all its sides is called an ‘incircle’. The total length of the smaller hexagon then becomes the lower bound of π and the length of the hexagon outside the circle is the upper bound. He realised that by increasing the number of sides of the polygon can make the bounds get closer to the value of Pi and increased the number of sides to 12,24,48 and 60. He argued that by increasing the number of sides will ultimately result in obtaining the original circle, thereby laying the foundation for the theory of limits. He ended up with the lower bound as 22/7 and the upper bound 223/71. He could not continue his research as his hometown Syracuse was invaded by Romans and was killed by one of the soldiers. His last words were ‘do not disturb my circles’, perhaps a reference to his continuing efforts to find the value of π to a greater accuracy.

Archimedes can be considered as the father of geometry. His contributions revolutionised geometry and his methods anticipated integral calculus. He invented the pulley and the hydraulic screw for drawing water from a well. He also discovered the law of hydrostatics. He formulated the law of levers which states that a smaller weight placed farther from a pivot can balance a much heavier weight closer to it. He famously said “Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand and I will move the earth”.

Mathematicians have found many expressions for π as a sum of infinite series that converge to its value. One such famous series is the Leibniz Series found in 1674 by the German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz, which is given below.

π = 4 ( 1 – 1/3 + 1/5 – 1/7 + 1/9 – ………….)

The Indian mathematical genius Ramanujan came up with a magnificent formula in 1910. The short form of the formula is as follows.

π = 9801/(1103 √8)

For practical applications an approximation is sufficient. Even NASA uses only the approximation 3.141592653589793 for its interplanetary navigation calculations.

It is not just an interesting and curious number. It is used for calculations in navigation, encryption, space exploration, video game development and even in medicine. As π is fundamental to spherical geometry, it is at the heart of positioning systems in GPS navigations. It also contributes significantly to cybersecurity. As it is an irrational number it is an excellent foundation for generating randomness required in encryption and securing communications. In the medical field, it helps to calculate blood flow rates and pressure differentials. In diagnostic tools such as CT scans and MRI, pi is an important component in mathematical algorithms and signal processing techniques.

This elegant, never-ending number demonstrates how mathematics transforms into practical applications that shape our world. The possibilities of what it can do are infinite as the number itself. It has become a symbol of beauty and complexity in mathematics. “It matters little who first arrives at an idea, rather what is significant is how far that idea can go.” said Sophie Germain.

Mathematics fans are intrigued by this irrational number and attempt to calculate it as far as they can. In March 2022, Emma Haruka Iwao of Japan calculated it to 100 trillion decimal places in Google Cloud. It had taken 157 days. The Guinness World Record for reciting the number from memory is held by Rajveer Meena of India for 70000 decimal places over 10 hours.

Happy Pi Day!

The author is a senior examiner of the International Baccalaureate in the UK and an educational consultant at the Overseas School of Colombo.

by R N A de Silva

Features

Sheer rise of Realpolitik making the world see the brink

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

As matters stand, there seems to be no credible evidence that the Indian state was aware of the impending torpedoing of the Iranian vessel but these acerbic-tongued politicians of Sri Lanka’s South would have the local public believe that the tragedy was triggered with India’s connivance. Likewise, India is accused of ‘embroiling’ Sri Lanka in the incident on account of seemingly having prior knowledge of it and not warning Sri Lanka about the impending disaster.

It is plain that a process is once again afoot to raise anti-India hysteria in Sri Lanka. An obligation is cast on the Sri Lankan government to ensure that incendiary speculation of the above kind is defeated and India-Sri Lanka relations are prevented from being in any way harmed. Proactive measures are needed by the Sri Lankan government and well meaning quarters to ensure that public discourse in such matters have a factual and rational basis. ‘Knowledge gaps’ could prove hazardous.

Meanwhile, there could be no doubt that Sri Lanka’s sovereignty was violated by the US because the sinking of the Iranian vessel took place in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone. While there is no international decrying of the incident, and this is to be regretted, Sri Lanka’s helplessness and small player status would enable the US to ‘get away with it’.

Could anything be done by the international community to hold the US to account over the act of lawlessness in question? None is the answer at present. This is because in the current ‘Global Disorder’ major powers could commit the gravest international irregularities with impunity. As the threadbare cliché declares, ‘Might is Right’….. or so it seems.

Unfortunately, the UN could only merely verbally denounce any violations of International Law by the world’s foremost powers. It cannot use countervailing force against violators of the law, for example, on account of the divided nature of the UN Security Council, whose permanent members have shown incapability of seeing eye-to-eye on grave matters relating to International Law and order over the decades.

The foregoing considerations could force the conclusion on uncritical sections that Political Realism or Realpolitik has won out in the end. A basic premise of the school of thought known as Political Realism is that power or force wielded by states and international actors determine the shape, direction and substance of international relations. This school stands in marked contrast to political idealists who essentially proclaim that moral norms and values determine the nature of local and international politics.

While, British political scientist Thomas Hobbes, for instance, was a proponent of Political Realism, political idealism has its roots in the teachings of Socrates, Plato and latterly Friedrich Hegel of Germany, to name just few such notables.

On the face of it, therefore, there is no getting way from the conclusion that coercive force is the deciding factor in international politics. If this were not so, US President Donald Trump in collaboration with Israeli Rightist Premier Benjamin Natanyahu could not have wielded the ‘big stick’, so to speak, on Iran, killed its Supreme Head of State, terrorized the Iranian public and gone ‘scot-free’. That is, currently, the US’ impunity seems to be limitless.

Moreover, the evidence is that the Western bloc is reuniting in the face of Iran’s threats to stymie the flow of oil from West Asia to the rest of the world. The recent G7 summit witnessed a coming together of the foremost powers of the global North to ensure that the West does not suffer grave negative consequences from any future blocking of western oil supplies.

Meanwhile, Israel is having a ‘free run’ of the Middle East, so to speak, picking out perceived adversarial powers, such as Lebanon, and militarily neutralizing them; once again with impunity. On the other hand, Iran has been bringing under assault, with no questions asked, Gulf states that are seen as allying with the US and Israel. West Asia is facing a compounded crisis and International Law seems to be helplessly silent.

Wittingly or unwittingly, matters at the heart of International Law and peace are being obfuscated by some pro-Trump administration commentators meanwhile. For example, retired US Navy Captain Brent Sadler has cited Article 51 of the UN Charter, which provides for the right to self or collective self-defence of UN member states in the face of armed attacks, as justifying the US sinking of the Iranian vessel (See page 2 of The Island of March 10, 2026). But the Article makes it clear that such measures could be resorted to by UN members only ‘ if an armed attack occurs’ against them and under no other circumstances. But no such thing happened in the incident in question and the US acted under a sheer threat perception.

Clearly, the US has violated the Article through its action and has once again demonstrated its tendency to arbitrarily use military might. The general drift of Sadler’s thinking is that in the face of pressing national priorities, obligations of a state under International Law could be side-stepped. This is a sure recipe for international anarchy because in such a policy environment states could pursue their national interests, irrespective of their merits, disregarding in the process their obligations towards the international community.

Moreover, Article 51 repeatedly reiterates the authority of the UN Security Council and the obligation of those states that act in self-defence to report to the Council and be guided by it. Sadler, therefore, could be said to have cited the Article very selectively, whereas, right along member states’ commitments to the UNSC are stressed.

However, it is beyond doubt that international anarchy has strengthened its grip over the world. While the US set destabilizing precedents after the crumbling of the Cold War that paved the way for the current anarchic situation, Russia further aggravated these degenerative trends through its invasion of Ukraine. Stepping back from anarchy has thus emerged as the prime challenge for the world community.

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoProf. Dunusinghe warns Lanka at serious risk due to ME war

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoWinds of Change:Geopolitics at the crossroads of South and Southeast Asia

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoHeat Index at ‘Caution Level’ in the Sabaragamuwa province and, Colombo, Gampaha, Kurunegala, Anuradhapura, Vavuniya, Hambanthota and Monaragala districts

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe final voyage of the Iranian warship sunk by the US

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoRoyal start favourites in historic Battle of the Blues