Features

Towards necessary exercise in discursive disentanglement?

(Prof. Sasanka Perera’s recent speech as guest speaker to the National Academy of Sciences)

In present times, there is an intriguing, but at times seemingly dangerous entanglement between science, belief and state policy or government action. This kind of phenomena range from the government’s sudden ban of Glyphosate in 2015; the state sponsorship of a conference on the air power of the mythical king Ravana to the layers of stories surrounding the advent of what is now popularly known as the Dammika Peniya. These are merely three well-known phenomena from a whole series of such phenomena in the country with varying impacts on social life, politics and commerce. As a collective of occurrences with their own structure of associated events, these phenomena have not been reckoned with seriously. We have not carefully reflected upon them and asked ourselves why they are more evident now, and what their broader consequences and reasons for manifestation might be. As a result, we do not have credible sociological explanations for these phenomena that goes beyond popular rhetoric. These phenomena are seemingly dangerous too, because many of them defy what we might think of as commonsense and leads in the direction of collective chaos and counter-productive action on the part of the state. And in this journey, ‘science’ is one of the most obvious casualties.

To me, all this points to a contradictory entanglement involving science, belief, and state policy when ideally such contradictory entanglements should not take place. By ‘science’ I do not merely mean the vast systems of knowledge that originated in the west, which now have global hegemony including in our country. Instead, science is any system of knowledge “concerned with the physical world” and phenomena emanating from this world along with formal “observations and systematic experimentation.”i In other words, a “science involves a pursuit of knowledge” that covers “general truths” as well as “the operations of fundamental laws.”ii In this sense, Ayurveda, Unnani, present day engineering, allopathic medicine or any other system of formal knowledge are mostly matters of science though the bases for their fundamentals would vary considerably from the more dominant post-enlightenment sciences to much older systems of knowledge.

Similarly, by ‘belief’, I mean not only matters of faith rooted in religion and tradition but also contemporary beliefs that are created by the repetitive circulation of ideas across media whether they are based on fact and science or not. Often, these ideas address contemporary issues and politics though they might be camouflaged in a rhetoric of the past, resort to specific conventions, and identity politics. And these associations are quite important today given the propensity for fake news and the enhanced ability of people to accept these ideas easily without being formally countered.

In the same sense, ‘state policy’ and actions linked to such policies are expected to be based on formal legal principles and empirical facts, and ideally should have nothing to do with matters of faith or untested assumptions and should benefit the polity.

Generally, I consider science, belief, and state policy to be independent discourses with their own epistemological routes and purposes though there will be close and necessary interactions among these such as between science and state policy. At other times, as we are seeing now, this association can be between belief and state policy where science might be eclipsed.

My intention today is to simply place in context three recent phenomena of this kind that are structurally very similar but contextually very different, which I think would explain to some extent how this amalgamation of discourses function, and the ways in which their politics manifest. As far as I am concerned, what I have to say today are simply preliminary thoughts about which I would like to think further and theorize.

Phenomenon 1: Glyphosate Ban

The use of the weedicide glyphosate was banned by presidential order in 2015. In a paper published in the same year, Jayasumana, Gunatilake and Siribaddana note that people in areas where kidney disease has become endemic have been exposed to multiple heavy metals and glyphosate.iii Their conclusion as far as I could see as a non-expert, was very vague, which amounted to the following observation: “Although we could not localize a single nephrotoxin as the culprit” “multiple heavy metals and glyphosates may play a role in the pathogenesis.”iv This is one of several public articulations related to this matter that has some semblance of what I may call scientific noise, but clearly inconclusive.

The ban was quite sudden and was implemented following on the heels of intense lobbying by Member of Parliament and Presidential Advisor, Reverend Athuraliye Rathana. He argued along with his supporters that this chemical caused chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu) in the North Central and Uva Provinces. But what is clear is no reliable and specific scientific evidence was offered by him or the President’s Office as the basis for the ban. In this overall process, it does not seem that the Registrar of Pesticides; Fertilizer Secretariat; Medical Research Institute and Tea Research Institute, all of whom could have presented valuable and more formal input into the decision were consulted. It almost seems that the ban found its genesis in the popular belief that chemicals are bad.

The fact that there is considerable prevalence of kidney disease in parts of the country is a fact, which needs to be more rigorously studied to work out its causes. Personally, I am not a supporter of excessive use of chemicals for anything including agriculture, and to the extent possible, I have made changes in my personal lifestyle to address this anxiety. But that kind of personal, emotional or popular anxieties cannot be the foundation for state level decision-making, particularly if the government and the people both subscribe to the idea of commercial agriculture and the eradication of hunger.

The consequences of the ban have been substantial in monetary terms. It caused production costs to increase substantially and the industry, particularly the tea sector, incurred losses up to 10-20 billion rupees annually while the ban lasted. Though the ban was eventually partially lifted, even at that time, no credible and conclusive data supporting the ban existed. So, it appears, that the ban was solely based on a popular and largely correct general belief of the negative impacts of chemicals, tempered by political rhetoric emanating from matters of faith and popular beliefs. I am sure we can all agree, while we can entertain popular beliefs or even conspiracy theories among people, if they are injected into broader politics and formation of state policy, that would have serious consequences as this event has shown. Part of the problem here is not only the undue credence given to freely circulating popular notions without situating them in the context of formal and reliable knowledge, information and science, but the ability of popular political leaders to convert untested ideas into practices of state policy and action without facing consequences.

Phenomenon 2: The State’s Embrace of Ravana

People of my generation will know that Ravana and his flying machine were merely elements in an interesting story in our youth while in some parts of the country specific local stories linked to this myth circulated. Unlike India and elsewhere in South Asia and in the east right up to Bali, there is no evidence of Ramayana performances which may have included a dramatization of the Ravana narrative in Sinhala cultural lore. But this situation has dramatically changed in recent times where Ravana’s popularity has rapidly increased among a cross section of the people, while his name and alleged historicity have also been openly embraced by the state.

By 2019, the story of Ravana had been directly appropriated by the Sri Lankan state and engrossed in a highly superficial but allegedly scientific discourse on aviation. In July 2019, Civil Aviation Authority of Sri Lankan organized a “conference of civil aviation experts, historians, archaeologists, scientists and geologists” in Katunayake.v The Authority’s Vice Chairman at the time, Shashi Danatunge told Indian media, “King Ravana was a genius. He was the first person to fly. He was an aviator. This is not mythology; it’s a fact. There needs to be a detailed research on this. In the next five years, we will prove this.”vi He further noted, “they had irrefutable facts to prove that Ravana was the pioneer and the first to fly using an aircraft.”vii The conference’s main conclusion was “that Ravana first flew from Sri Lanka to today’s India 5,000 years ago and came back.”viii Many conference participants in their own peculiar wisdom, dismissed the powerful stories narrating Ravana’s kidnapping of Lord Rama’s wife Sita, as a mere “Indian version.”ix For them, this was not possible because Ravana was a noble king.”x

Intriguingly, one part of the myth cluster became a fact while another became fiction based simply on nothing more concrete than emotional and nationalist appeal. The ideas expressed in public on this matter were not private articulations of individuals. Particularly the Vice Chairman of Civil Aviation was speaking as a representative of a state agency. Also, the general conclusions of the conference and the acceptance of the Ravana story as historical fact could simply not be entrained by formal historiography and archaeology.

By 2020, the same agency took its sense of scientificity of these claims even further by launching a research project looking for evidence of Ravana’s flying and his “aviation routes.”xi The theme of the project was, “King Ravana and the ancient domination of aerial routes now lost.”xii Towards this, the Civil Aviation Authority placed advertisements in national newspapers asking people to send in evidence they may have. The purported scientific objective and the reason for the Civil Aviation Authority’ central involvement in this state-sponsored effort was explained as follows: 1) Because the Civil Aviation Authority was “the main aviation regulatory authority in Sri Lanka,” it was the most logical entity to host such and effort, and 2) Because “there are multiple stories over the years about Ravana flying aircrafts and covering these routes” there was a necessity “to study this matter.”xiii

Though there are seemingly rational and seemingly scientific ‘noises’ in this episode, the entire exercise is enveloped in taking myth as fact, and that too, with the direct participation of the state.

Phenomenon 3: The Advent of the Dammika Peniya

Now we come to the advent of the Dammika Peniya which is formally known as ‘ශ්රී වීර භද්රධම්ම කොරෝනා නිවාරණ ප්රතිශක්ති ජීව පානය’ (Shri Vira Bhdradhamma Corona Nivaranana Prathishakthi Jiva Panaya). According to its inventor, Mr Dammika Bandara, the formula for the syrup was given to him by Goddess Kali in a dream. This is a crucial point in which the genesis of this syrup differs from the more formal discourses of knowledge in Ayurveda and Sinhala medicine, within which this claim is located.

It was a claim protected by rhetoric of local medical superiority, power of ancient knowledge and very loud articulations of cultural and political nationalism. But certain things need to be understood clearly. Even within the structure of faith and belief in Sinhala culture, goddess Kali, the alleged ultimate progenitor of the syrup is not known for healing. She is seen more as a powerful deity but with considerable destructive potential. More typically associated with healing is goddess Pattini. So, the claim seems to be out of place even in the context of conventional Sinhala myth and belief. Second, though Ayurveda and Sinhala medicine have associations with faith and ritual, the bulk of their formal discourses on medicine are based on experimentation, repetitive practice and fine-tuning and formally scripted knowledge or that which is handed over word of mouth across generations. My maternal grandfather wrote two books in the early 1970s after he had retired from his Ayurvedic practice and teaching. The first was called Rasayana saha Vajikarana (රසායන සහ වාජිකරණ) in which he presented a specific body of knowledge already known to his field, but with fine-tuning offered by his own practice and studies. The second, called Avinishchitha Aushada (අවිනිශ්චිත ඖෂධ) was very different. It dealt with a series of plants whose medical utility was unknown or unsure. In it, he dealt with the unknown, based on both generations of institutionalized uncertainty as well as conjecture on his part, but based on his long years of practice and observation. Both these point to the nature of the scientific discourse of contemporary Ayurveda.

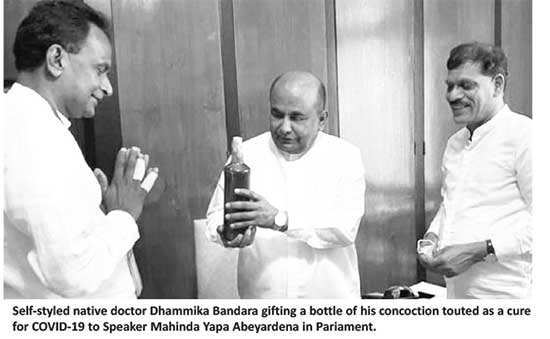

Compared to this kind of background, Mr Bandara offers a set of contradictions. He is not a medical practitioner, but a mason by profession who runs a small Kali shrine in his neighborhood. However, his claim over having invented a treatment for Corona received massive publicity via media outlets supportive of the state and unreserved public support from numerous local and national political leaders including the Minister of Health and the Speaker of Parliament all of whom consumed the concoction in public along with some of their colleagues. This does not tantamount to formal state support as in the other two cases. But such open adulation and support by senior members of the government is a public performance of confidence for an untested medication with a dubious claim. These actions played a major role in ensuring large numbers of people flocking to Mr Bandara’s house in Kegalle in search of this ‘miracle’ drug – in the midst of a pandemic. This is not a general condemnation of traditional medicine. In the 1950s, the establishment of the Ayurvedic Research Institute was to offer traditional medicine a sound research and dissemination base and bring it on par with formal understanding of science. But Dammika Peniya has no such provenance; it simply came from a dream according to its inventor himself, and such provenance simply cannot be the basis for its public adulation by political leaders. Most criticisms of the concoction and its provenance were vociferously put down in public as acts of anti-nationalism and lack of respect for traditional culture. A dubious study involving several colleagues of the Wathupitiwala Hospital and a handful of test cases had taken place though it is not clear to me if this exercise even had ethical clearance. A committee consisting of medical professionals has now been appointed to undertake a clinical study of the concoction using acceptable clinical trial criteria and practices. Its results have not yet been published.

What does all this mean?

All these three incidents have several obvious things in common:

the core notions in all stories are based on popular assumptions and untested ideas;

they all have powerful political and state support directly or indirectly;

their main arguments are governed by belief whether tempered by faith or by the mere repetition of mass circulating non-facts; and

in all cases, science in the formal sense – from allopathic medicine, Ayurveda and natural sciences to archaeology and history – have been dispelled even though such input could have more sensibly impacted these discourses if they were formally made available.

Moreover, the public manifestation and power of these discourses became possible due to the very clear inability of the public services directly associated with these contexts to be guided by formally collected data and scientific conclusions and their inability to advise their political Masters, and withstand the pressures of political interference. Such political interference is obviously not based on advice from subject experts or from a clear political vision, but from short-term political agendas for popular mobilization. This main conditionality allowed these unstable claims to become part of national politics and in some cases become policy or in the very least lead to actions sanctioned by the state.

But how does one explain the massive public support especially for the last two incidents. I have noticed for many years that people in our country, and particularly the Sinhalas seem to have a desperate urge to be part of grand historical claims and narratives. But I have not yet been able to gather adequate data or theorize what might be going on. But one can tentatively make some observations. The rediscovery of Ravana and brining him from the pages of myth and epic narrative of the Ramayana to state-sponsored formal discourses of populist and non-empirical historicization, and therefore formal reiteration of myth itself shows the urge to control what might be thought of as a popular and powerful narrative of the past. The way in which Sinhalas have reinvented Ravana over the last decade or so is not only as an aviator, but also as an engineer, medical expert, inventor, scientist and scholar. And this is done within an idiom of nationalist discourse that insists a pre-Vijayan and wholly Sri Lankan civilization once existed in which Ravana is a central attraction. These claims also assert this civilization was somehow superior to the cultural landscape across the ocean in the rest of South Asia. This seems to me to be more like what anthropologists would call millenarian mythmaking where Ravana appears at least in part as a millenarian hero. Generally, millenarian stories, beliefs and heroes have to do with delivering a society from danger, introduction of new ideas and technologies to ensure the safety of a collective, and so on. Such stories generally manifest in times of crisis. In the case of the Ravana story, the preoccupation is to recreate an important place for Lanka in the broader political history of South Asia in the context of a politically unstable present.

Even the story of the Dammika Peniya has some of these millenarian features. After all, it was presented as a very local remedy for COVID 19 based on a lost Sri Lankan body of scientific knowledge delivered directly by a goddess in a dream. And that too at a time when people were desperate to be safe and keen to protect their livelihoods from the vagaries of Corona virus at a time the state’s effort at controlling it appeared to be faltering. The Peniya seemed to be a sign of miraculous deliverance from the island’s past glory emerging in the midst of its chaotic present.

To end this preliminary sketch let me refer to a final comment. It seems to me, these kinds of stories emerge in times of crises – be these emotional, social, or political crises. This is not unique to Sri Lanka, and can also be seen in many other parts of the world in structurally similar circumstances. These stories have their genesis in realms of conjecture. I am not objecting to the deployment of conjecture as such. Most good ideas in all our disciplines would often begin with conjecture. As we know, the philosophy of science has shown us the importance of “assumptions, foundations, methods” and “implications of science.”xiv Reflections in philosophy of science also indicate the efforts to distinguish between what is considered science and what is thought of as non-science.xv It is in the latter domain where untested conjecture would generally be located until they can be given a basis in science or dispelled.

In this general context, it seems to me, these stories allow people to be part of a more powerful and often a winning idea of history and hyper-real present even though that domain of belief might have very little or nothing to do with lived reality as such. Partly, these can also be seen as coping mechanisms in difficult and turbulent times. But these are clearly not remedies for very real socio-political or public health issues that can be utilized brazenly by the state as long as their core ideas remain in domains of belief and conjecture.

The collective failure that typifies our situation is the inability of many people to understand this commonsense and as a result, become dangerously entangled in the internal logic of these stories, which have no external empirical foundations except for the real-life calamities some of them might generate. It is also likely our political leaders consciously and deliberately promote these stories and phenomena to divert people’s attention from evolving crises.

In this situation, I find it unfortunate that Sri Lankan social sciences have not yet spent the time to collect these stories and study them more carefully in their border social and political contexts and offer a more coherent, empirically-based, and nuanced theoretical explanation.

(Sasanka Perera is a trained anthropologist and is a professor at South Asian University in New Delhi. This is the text of a guest lecture delivered at the Induction Ceremony of the National Academy of Sciences of Sri Lanka on 22 January 2021)

Features

Sheer rise of Realpolitik making the world see the brink

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

As matters stand, there seems to be no credible evidence that the Indian state was aware of the impending torpedoing of the Iranian vessel but these acerbic-tongued politicians of Sri Lanka’s South would have the local public believe that the tragedy was triggered with India’s connivance. Likewise, India is accused of ‘embroiling’ Sri Lanka in the incident on account of seemingly having prior knowledge of it and not warning Sri Lanka about the impending disaster.

It is plain that a process is once again afoot to raise anti-India hysteria in Sri Lanka. An obligation is cast on the Sri Lankan government to ensure that incendiary speculation of the above kind is defeated and India-Sri Lanka relations are prevented from being in any way harmed. Proactive measures are needed by the Sri Lankan government and well meaning quarters to ensure that public discourse in such matters have a factual and rational basis. ‘Knowledge gaps’ could prove hazardous.

Meanwhile, there could be no doubt that Sri Lanka’s sovereignty was violated by the US because the sinking of the Iranian vessel took place in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone. While there is no international decrying of the incident, and this is to be regretted, Sri Lanka’s helplessness and small player status would enable the US to ‘get away with it’.

Could anything be done by the international community to hold the US to account over the act of lawlessness in question? None is the answer at present. This is because in the current ‘Global Disorder’ major powers could commit the gravest international irregularities with impunity. As the threadbare cliché declares, ‘Might is Right’….. or so it seems.

Unfortunately, the UN could only merely verbally denounce any violations of International Law by the world’s foremost powers. It cannot use countervailing force against violators of the law, for example, on account of the divided nature of the UN Security Council, whose permanent members have shown incapability of seeing eye-to-eye on grave matters relating to International Law and order over the decades.

The foregoing considerations could force the conclusion on uncritical sections that Political Realism or Realpolitik has won out in the end. A basic premise of the school of thought known as Political Realism is that power or force wielded by states and international actors determine the shape, direction and substance of international relations. This school stands in marked contrast to political idealists who essentially proclaim that moral norms and values determine the nature of local and international politics.

While, British political scientist Thomas Hobbes, for instance, was a proponent of Political Realism, political idealism has its roots in the teachings of Socrates, Plato and latterly Friedrich Hegel of Germany, to name just few such notables.

On the face of it, therefore, there is no getting way from the conclusion that coercive force is the deciding factor in international politics. If this were not so, US President Donald Trump in collaboration with Israeli Rightist Premier Benjamin Natanyahu could not have wielded the ‘big stick’, so to speak, on Iran, killed its Supreme Head of State, terrorized the Iranian public and gone ‘scot-free’. That is, currently, the US’ impunity seems to be limitless.

Moreover, the evidence is that the Western bloc is reuniting in the face of Iran’s threats to stymie the flow of oil from West Asia to the rest of the world. The recent G7 summit witnessed a coming together of the foremost powers of the global North to ensure that the West does not suffer grave negative consequences from any future blocking of western oil supplies.

Meanwhile, Israel is having a ‘free run’ of the Middle East, so to speak, picking out perceived adversarial powers, such as Lebanon, and militarily neutralizing them; once again with impunity. On the other hand, Iran has been bringing under assault, with no questions asked, Gulf states that are seen as allying with the US and Israel. West Asia is facing a compounded crisis and International Law seems to be helplessly silent.

Wittingly or unwittingly, matters at the heart of International Law and peace are being obfuscated by some pro-Trump administration commentators meanwhile. For example, retired US Navy Captain Brent Sadler has cited Article 51 of the UN Charter, which provides for the right to self or collective self-defence of UN member states in the face of armed attacks, as justifying the US sinking of the Iranian vessel (See page 2 of The Island of March 10, 2026). But the Article makes it clear that such measures could be resorted to by UN members only ‘ if an armed attack occurs’ against them and under no other circumstances. But no such thing happened in the incident in question and the US acted under a sheer threat perception.

Clearly, the US has violated the Article through its action and has once again demonstrated its tendency to arbitrarily use military might. The general drift of Sadler’s thinking is that in the face of pressing national priorities, obligations of a state under International Law could be side-stepped. This is a sure recipe for international anarchy because in such a policy environment states could pursue their national interests, irrespective of their merits, disregarding in the process their obligations towards the international community.

Moreover, Article 51 repeatedly reiterates the authority of the UN Security Council and the obligation of those states that act in self-defence to report to the Council and be guided by it. Sadler, therefore, could be said to have cited the Article very selectively, whereas, right along member states’ commitments to the UNSC are stressed.

However, it is beyond doubt that international anarchy has strengthened its grip over the world. While the US set destabilizing precedents after the crumbling of the Cold War that paved the way for the current anarchic situation, Russia further aggravated these degenerative trends through its invasion of Ukraine. Stepping back from anarchy has thus emerged as the prime challenge for the world community.

Features

A Tribute to Professor H. L. Seneviratne – Part II

A Living Legend of the Peradeniya Tradition:

(First part of this article appeared yesterday)

H.L. Seneviratne’s tenure at the University of Virginia was marked not only by his ethnographic rigour but also by his profound dedication to the preservation and study of South Asian film culture. Recognising that cinema is often the most vital expression of a society’s aspirations and anxieties, he played a central role in curating what is now one of the most significant Indian film collections in the United States. His approach to curation was never merely archival; it was informed by his anthropological work, treating films as primary texts for understanding the ideological shifts within the subcontinent

The collection he helped build at the UVA Library, particularly within the Clemons Library holdings, serves as a comprehensive survey of the Indian ‘Parallel Cinema’ movement and the works of legendary auteurs. This includes the filmographies of directors such as Satyajit Ray, whose nuanced portrayals of the Indian middle class and rural poverty provided a cinematic counterpart to H.L. Seneviratne’s own academic interests in social change. By prioritising the works of figures such as Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak, H.L. Seneviratne ensured that students and scholars had access to films that wrestled with the complex legacies of colonialism, partition, and the struggle for national identity.

These films represent the ‘Parallel Cinema’ movement of West Bengal rather than the commercial Hindi industry of Mumbai. H.L. Seneviratne’s focus initially cantered on those world-renowned Bengali masters; it eventually broadened to encompass the distinct cinematic languages of the South. These films refer to the specific masterpieces from the Malayalam and Tamil regions—such as the meditative realism of Adoor Gopalakrishnan or the stylistic innovations of Mani Ratnam—which are culturally and linguistically distinct from the Bengali works. Essentially, H.L. Seneviratne is moving from the specific (Bengal) to the panoramic, ensuring that the curatorial work of H.L. Seneviratne was not just a ‘Greatest Hits of Kolkata’ but a truly national representation of Indian artistry. These films were selected for their ability to articulate internal critiques of Indian society, often focusing on issues of caste, gender, and the impact of modernisation on traditional life. Through this collection, H.L. Seneviratne positioned cinema as a tool for exposing the social dynamics that often remain hidden in traditional historical records, much like the hidden political rituals he uncovered in his early research.

Beyond the films themselves, H.L. Seneviratne integrated these visual resources into his curriculum, fostering a generation of scholars who understood the power of the image in South Asian politics. He frequently used these screenings to illustrate the conflation of past and present, showing how modern cinema often reworks ancient myths to serve contemporary political agendas. His legacy at the University of Virginia therefore encompasses both a rigorous body of writing that deconstructed the work of the kings and a vivid archive of films that continues to document the work of culture in a rapidly changing world.

In his lectures on Sri Lankan cinema, H.L. Seneviratne has frequently championed Lester James Peries as the ‘father of authentic Sinhala cinema.’ He views Peries’s 1956 film Rekava (Line of Destiny) as a watershed moment that liberated the local industry from the formulaic influence of South Indian commercial films. For H.L. Seneviratne, Peries was not just a filmmaker but an ethnographer of the screen. He often points to Peries’s ability to capture the subtle rhythms of rural life and the decline of the feudal elite, most notably in his masterpiece Gamperaliya, as a visual parallel to his own research into the transformation of traditional authority. H.L. Seneviratne argues that Peries provided a realistic way of seeing for the nation, one that eschewed nationalist caricature in favour of complex human emotion.

However, H.L. Seneviratne’s praise for Peries is often tempered by a critique of the broader visual nationalism that followed. He has expressed concern that later filmmakers sometimes misappropriated Peries’s indigenous style to promote a narrow, majoritarian view of history. In his view, while Peries opened the door to an authentic Sri Lankan identity, the state and subsequent commercial interests often used that same door to usher in a simplified, heroic past. This critique aligns with his broader academic stance against the rationalization of culture for political ends.

Constitutional Governance:

H.L. Seneviratne’s support for independent commissions is best described as a hopeful pragmatism; he views them as essential, albeit fragile, instruments for diffusing the hyper-concentration of executive power. Writing to Colombo Page and several news tabloids, H.L. Seneviratne addresses the democratic deficit by creating a structural buffer between partisan interests and public institutions, theoretically ensuring that the judiciary, police, and civil service operate on merit rather than political whim. However, he remains deeply aware that these commissions are not a panacea and are indeed inherently susceptible to the ‘politics of patronage.’

In cultures where power is traditionally exercised through personal loyalties, there is a constant risk that these bodies will be subverted through the appointment of hidden partisans or rendered toothless through administrative sabotage. Thus, while H.L. Seneviratne advocates for them as a means to transition a state from a patron-client culture to a rule-of-law framework, his anthropological lens suggests that the success of such commissions depends less on the law itself and more on the sustained pressure of civil society to keep them honest.

Whether discussing the nuances of a film’s narrative or the complexities of a constitutional clause, H.L. Seneviratne’s approach remains consistent in its focus on the spirit behind the institution. He maintains that a healthy democracy requires more than just the right laws or the right symbols; it requires a citizenry and a clergy capable of critical self-reflection. His career at the University of Virginia and his continued engagement with Sri Lankan public life stand as a testament to the idea that the intellectual’s work is never truly finished until the work of the people is fully realized.

In the context of H.L. Seneviratne’s philosophy, as discussed in his work of the kings ‘the work of the people’ is far more than a populist catchphrase; it represents the practical application of critical consciousness within a democracy. Rather than defining ‘work’ as labour or voting, H.L. Seneviratne views it as the transition of a population from passive subjects to an active, self-reflective citizenry. This means that a democracy is only truly ‘realized’ when the public possesses the intellectual autonomy to look beyond the ‘right laws’ or ‘right symbols’ and instead engage with the underlying spirit of their institutions. For H.L. Seneviratne, this work is specifically tied to the ability of the people—including influential groups like the clergy—to perform rigorous self-critique, ensuring that they are not merely following tradition or authority, but are actively sustaining the ethical health of the nation. It is a perpetual process of civic education and moral vigilance that moves a society from the ‘paper’ democracy of a constitution to a lived reality of accountability and insight.

This decline of the ‘intellectual monk’ had a catastrophic impact on the political landscape, particularly surrounding the watershed moment of 1956 and the ‘Sinhala Only’ movement. H.L. Seneviratne posits that when the Sangha exchanged their role as impartial moral advisors for that of political kingmakers, they became the primary obstacle to ethnic reconciliation. He suggests that politicians, fearing the immense grassroots influence of the monks, entered a state of monachophobia, where they felt unable to propose pluralistic or fair policies toward minority communities for fear of being branded as traitors to the faith. In H.L. Seneviratne’s framework, the monk’s transition from a social servant to a political vanguard effectively trapped the state in a cycle of majoritarian nationalism from which it has yet to escape.

H.L. Seneviratne’s work serves as a multifaceted critique of the modern Sri Lankan state and its cultural foundations. Whether he is dissecting what he sees as the betrayal of the monastic ideal or celebrating the humanistic vision of an Indian filmmaker, his goal remains the same: to champion a world where intellect and compassion are not sacrificed on the altar of political power. His legacy at the University of Virginia and his continued voice in Sri Lankan discourse remind us that the work of the intellectual is to provide a moral compass even, indeed especially, when the nation has lost its way.

(Concluded)

by Professor

M. W. Amarasiri de Silva

Features

Musical journey of Nilanka Anjalee …

Nilanka Anjalee Wickramasinghe is, in fact, a reputed doctor, but the plus factor is that she has an awesome singing voice, as well., which stands as a reminder that music and intellect can harmonise beautifully.

Nilanka Anjalee Wickramasinghe is, in fact, a reputed doctor, but the plus factor is that she has an awesome singing voice, as well., which stands as a reminder that music and intellect can harmonise beautifully.

Well, our spotlight today is on ‘Nilanka – the Singer,’ and not ‘Nilanka – the Singing Doctor!’

Nilanka’s journey in music began at an early age, nurtured by an ear finely tuned to nuance and a heart that sought expression beyond words.

Under the tutelage of her singing teachers, she went on to achieve the A.T.C.L. Diploma in Piano and the L.T.C.L. Diploma in Vocals from Trinity College, London – qualifications recognised internationally for their rigor and artistry.

These achievements formally certified her as a teacher and performer in both opera singing and piano music, while her Performer’s Certificate for singing attested to her flair on stage.

Nilanka believes that music must move the listener, not merely impress them, emphasising that “technique is a language, but emotion is the message,” and that conviction shines through in her stage presence –serene yet powerful, intimate yet commanding.

Her YouTube channel, Facebook and Instagram pages, “Nilanka Anjalee,” have become a window into her evolving artistry.

Here, audiences find not only her elegant renditions of local and international pieces but also her original songs, which reveal a reflective and modern voice with a timeless sensibility.

Each performance – whether a haunting ballad or a jubilant interpretation of a traditional hymn – carries her signature blend of technical finesse and emotional depth.

Beyond the concert hall and digital stage, Nilanka’s music is driven by a deep commitment to meaning.

Her work often reflects her belief in empathy, inner balance, and the beauty of simplicity—values that give her performances their quiet strength.

She says she continues to collaborate with musicians across genres, composing and performing pieces that reflect both her classical discipline and her contemporary outlook.

Widely acclaimed for her ability to adapt to both formal and modern stages, with equal grace, and with her growing repertoire, Nilanka has become a sought-after soloist at concerts and special events,

For those who seek to experience her artistry, firsthand, Nilanka Anjalee says she can be contacted for live performances and collaborations through her official channels.

Her voice – refined, resonant, and resolutely her own – reminds us that music, at its core, is not about perfection, but truth.

Dr. Nilanka Anjalee Wickramasinghe also indicated that her newest single, an original, titled ‘Koloba Ahasa Yata,’ with lyrics, melody and singing all done by her, is scheduled for release this month (March)

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoUniversity of Wolverhampton confirms Ranil was officially invited

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoFemale lawyer given 12 years RI for preparing forged deeds for Borella land

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoLibrary crisis hits Pera university

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA

-

News7 days ago

News7 days ago‘IRIS Dena was Indian Navy guest, hit without warning’, Iran warns US of bitter regret

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoSri Lanka evacuates crew of second Iranian vessel after US sunk IRIS Dena