Opinion

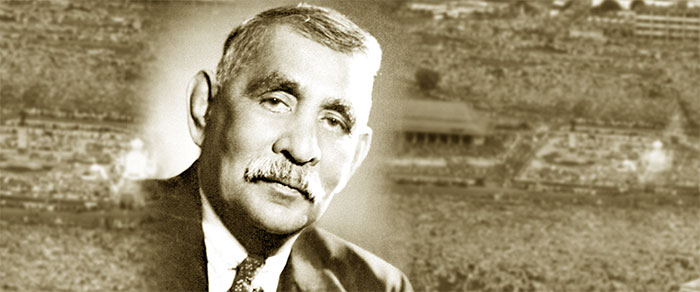

The Vision Splendid of D S Senanayake

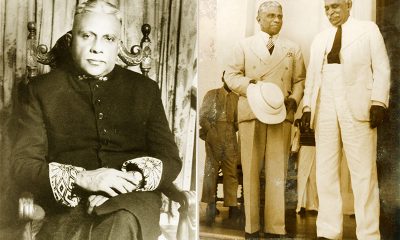

On 05 October, 2022, The Island carried an article by Dr C. S. Weeraratna with the title “Deteriorating rural economy, and food Security”. On reading this, I was motivated to send a chapter from the biography of D. S. Senanayake by H. A. J. Hulugalle titled ‘The Vision Splendid.’ The book has much more information on Senanayake’s plan for Sri Lanka’s Agricultural development. It deals with Senanayake’s passion for the subject, as well as his in-depth knowledge, acquired over half a century. Even today, one could be inspired by how he approached Food and Agriculture.

D.S.Senanayake’s

birthday falls on the 20th of October

– A.H.

In the book D. S. Senanayake published in 1935, he said: “It is a remarkable fact that we in Ceylon, while repeating in season and out, that ours is an agricultural country and that her prosperity is inextricably bound up with her agricultural progress, should yet be apparently content to pay a bill in a year of depression (1933) of nearly 87 million rupees for the imports of our food and drink”. Twenty years after his death, the cost of imports of ‘food exceed the figure of a thousand million.

Senanayake felt that the decline of food production in Ceylon in modern times was due to the fact that this form of agriculture was despised by the educated and well-to-do. The main burden of food production was borne by the land-starved and debt-ridden peasantry. “It is almost as if”, he wrote, “that some sense of inferiority that is sometimes seen to overwhelm a Ceylonese in the presence of his European brother has also attached itself to the native products. Rice and other grains, eggs, onions, chillies and ginger are humble, though useful, commodities. Fruit has a status only a trifle higher than these. To be engaged in their production is something to be ashamed of”.

The commercial and plantation crops were not only more respectable: they were more profitable in good times, and commanded credit from bankers and brokers. Senanayake had no illusions about the inevitable result of neglecting food production. He said that “the great attraction of the commercial crops, the dignity that seemed to attach to them, the comparative ease with large returns for outlay came in, blinded the wealthier Ceylonese to the dangers lying hidden beneath their glamour and drew them away from the essentially safer and sounder, though less splendid, cultivation of products to provide a direct means of sustenance to the home population. The middle classes emulated their wealthier brethren, and the peasant, left to his own devices, was content to scratch the soil and receive just whatever Nature provided”.

Today, the gravest problem in Ceylon as in some other developing countries is the rapid increase of population outstripping economic development. The Nobel Prize winner and Oxford Professor of Economics, Sir John Hicks, after making a study of the Ceylon problem, said that “with birth and death rates as they are at present, the population will go on increasing rapidly, and there is no possible development which could enable an unlimited population to support itself on the Island”.

Senanayake published his book before malaria was controlled during the second world war, causing a ‘population explosion’. But he foresaw the problem to which Sir John Hicks and other writers on the subject have drawn attention. He wrote: “By all laws relating to the growth of population formulated by competent statisticians, the rate of increase of the population of this Island will continue to be maintained. It is obvious, then, that the problem of how to sustain these increasing numbers cannot much longer be ignored: it has perforce to be fairly and squarely faced, and a solution urgently sought”.

For him, the development of agriculture was the highest form of patriotism in the conditions in which Ceylon found herself. He quoted with approval the following passage from the Businessmen’s Commission in the United States:

“Agriculture is not merely a way of making money by raising crops; it is not merely an industry or a business; it is essentially a public function or service performed by private individuals for the care and use of the land in the national interest: and the farmers in the course of securing a living and a private profit are the custodians of the basis of the national life. Agriculture is therefore affected with a clear and unquestionable public interest, and its status is a matter of national concern calling for deliberate and far-sighted policies, not only to conserve the national and human resources involved in it but to provide the national security, promote a well-rounded prosperity and secure social and political stability”.

The Land Bill, which Senanayake introduced in the State Council in 1933 was the direct result of a Report made by the Executive Committee of Agriculture of which he was the Chairman.

The Report said: “When one considers the economic condition of the Ceylonese people, no amount of optimism can conceal the gradual downward trend which has set in, or the signs of grave alarm for the future. The avenues of lucrative employment are rapidly getting filled up, and unless fresh avenues are explored we will soon be placed in a grave situation.

“The university and colleges and schools are turning out large numbers of young men with high educational qualifications, but one must be blind not to see that a large proportion of these young men can never hope to obtain lucrative employment of the kind which they expect. The future generation of middle class Ceylonese cannot all hope to find employment in the professions and clerical services. There is only one direction to which they can turn for their economic salvation: and that is the land. From ancient times the fruits of the soil have been almost the only source of the wealth of this country, and this will be true for many years to come. One remedy for the ills, which a continuance of the present state of affairs is bound to intensify, is to provide middleclass Ceylonese with land and the facilities for developing land, and thus foster the establishment of a class of rural gentry which did exist at one time but is now fast disappearing”.

In these days of socialist planning, it may be a heresy to talk of a landed gentry but the object of the land reforms now being implemented is not very different from those of the Executive Committee. Its Report was endorsed by the State Council, ratified by the Governor and approved by the Secretary of State. But we are as far as ever from the goal of a well-educated and resident farming class. Senanayake’s book was a blue-print for agricultural development. Had it been acted upon vigorously after his death, the Island’s economy would undoubtedly be in a better shape than it is today.

He did not expect the private agricultural sector to solve the country’s food problem without a massive contribution by the State. In the following passage from Agriculture and Patriotism he indicated how the State could help:

“As our present Governor, Sir Edward Stubbs, remarked on one occasion, it is not enough to recognise the fact that Ceylon is not self-sufficient, we must act upon it. The new land policy which Sir Hugh Clifford may be said to have inaugurated has settled the question as regards the proper functions of Government when dealing with what is known in Ceylon as ‘Crown Land’. It will always be one of the most primary and imperative duties to guard the land – this great asset of the people, of the taxpayers – from encroachment by individuals or groups of individuals; and further, to the, best of its ability, to see that it is alienated in the manner most nicely calculated to promote the prosperity of the Island and the highest interests of its inhabitants”.

An idea of the ground covered by Senanayake’s book can be gained by a glance at its chapter headings: Population and Food Supply, The New Land Policy, The New-Tenure and Colonization, The Tradition of Irrigation, Irrigation Policy, The State and Agricultural Credit, Debt Conciliation and Normal Financing, Intensive Cultivation, Dietetics and Husbandry, The Faith of Co-operation, The Practice of Co-operation, Marketing, Agricultural Labour.

The Co-operative Movement was very close to Senanayake’s heart. It was introduced to Ceylon by the Colonial Government but it was taken up by him arid expanded. A fuller account of the Co-operative movement in Ceylon will be found in a later chapter.

Senanayake recognized the need for giving financial assistance to the new colonists under irrigation schemes. He stressed the importance of intensive cultivation, especially in areas near towns, and drew attention to the ingenious system of agriculture practiced by the French small ‘maraicher’, with the knowledge and experience which only decades of careful thought, attention and experiment could have engendered. He also encouraged men like Dr. Lucius Nicholls, who was then in the Ceylon medical service, to carry out investigations on the food values of the diets of various classes of the population and suggest how they could be improved. Agricultural education was another subject which claimed his attention. “Few unofficials”, he wrote, “have done so much to advance the cause of agriculture in this country as Father LeGoc O.M.1. Quite apart from the work he is doing in promoting in the students of St. Joseph’s College a liking for agricultural activity, his researches in the field of biology have been of very great use to the officers of the Government Departments. It is perhaps little known, for instance, that a long step was made possible in the cultivation of suitable fodder grasses by the results achieved by the Rev. Father’s experimentation. Could we but have a few more in the Island who would, for the love of agriculture and in recognition of its importance in the scheme of our well- being, be prepared to assist us to build our prosperity on the firm basis of tilling and grazing, we should have reason to account ourselves a most fortunate people”.

It may be mentioned in this connection that Sir Geoffrey Butler’s reference, quoted in an earlier chapter of this book, to the Cambridge men he met in Ceylon, one of whom had worked in the Cavendish Laboratory, was to Father Le Goc who was a con- temporary there of Lord Rutherford.

Sir Arthur Ranasinha has disclosed in his memoirs the genesis of the book Agriculture and Patriotism. “As his agricultural policy became crystallized”, writes Ranasinha, “I suggested to him that it would be desirable to outline his ideas in a series of Press articles. The suggestion came to my mind when I saw in the Press some articles on the development of arid Palestine by men and money of the Zionist Movement. ‘D.S.’ accepted my suggestion with enthusiasm, and we began thinking out, discussing and writing a series of articles to be published in a newspaper. These articles were later collected and published as a booklet entitled “Agriculture and Patriotism”.

A series of articles was written by the present writer in the Ceylon Daily News after a visit of several weeks to Palestine at the beginning of 1935. I lived in the Jewish settlements such as Rehovath, Givat Brenner and Emek. During this trip I was sent to Golda Meir, who was then in charge of a labour office and she invited me to her home in Tel Aviv on the sand dunes. Later she was Prime Minister of Israel which was previously a part of the British Mandate of Palestine. I brought back to Ceylon a book in English called The Fellah’s Farm, by a Mr. Villeani, of the agicultural experts. He had taken an Arab farmer and put him to work on an allotment of land. A neighbouring land under the same conditions was cultivated by methods used in modern farming. The Arab’s Land was worked under the supervision of the Superintendent and all his work was indexed in detail. Villeani had gathered interesting material enabling him to compare both methods of agiculture. I gave this book to Senanayake who was attracted by this kind of research and I have been told by Sir Arthur Ranasinha, who helped Senanayake with the book entitled Agriculture and Patriotism, that the idea of writing it came from The Fellah’s Farm.

Opinion

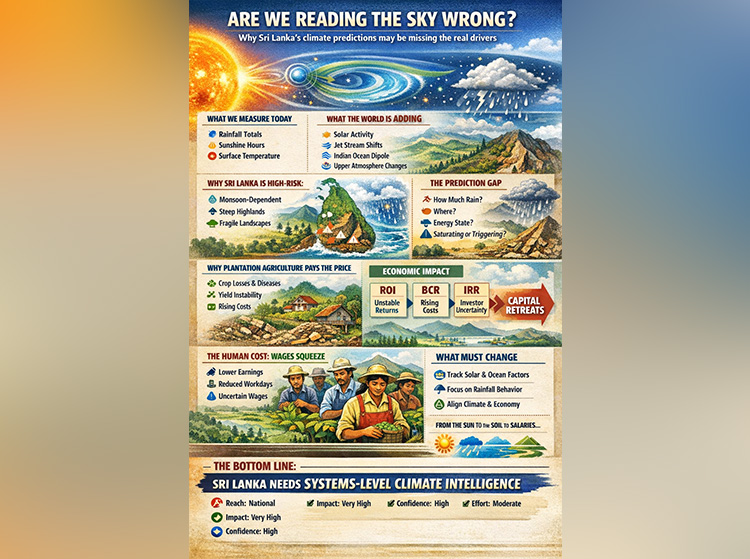

Are we reading the sky wrong?

Rethinking climate prediction, disasters, and plantation economics in Sri Lanka

For decades, Sri Lanka has interpreted climate through a narrow lens. Rainfall totals, sunshine hours, and surface temperatures dominate forecasts, policy briefings, and disaster warnings. These indicators once served an agrarian island reasonably well. But in an era of intensifying extremes—flash floods, sudden landslides, prolonged dry spells within “normal” monsoons—the question can no longer be avoided: are we measuring the climate correctly, or merely measuring what is easiest to observe?

Across the world, climate science has quietly moved beyond a purely local view of weather. Researchers increasingly recognise that Earth’s climate system is not sealed off from the rest of the universe. Solar activity, upper-atmospheric dynamics, ocean–atmosphere coupling, and geomagnetic disturbances all influence how energy moves through the climate system. These forces do not create rain or drought by themselves, but they shape how weather behaves—its timing, intensity, and spatial concentration.

Sri Lanka’s forecasting framework, however, remains largely grounded in twentieth-century assumptions. It asks how much rain will fall, where it will fall, and over how many days. What it rarely asks is whether the rainfall will arrive as steady saturation or violent cloudbursts; whether soils are already at failure thresholds; or whether larger atmospheric energy patterns are priming the region for extremes. As a result, disasters are repeatedly described as “unexpected,” even when the conditions that produced them were slowly assembling.

This blind spot matters because Sri Lanka is unusually sensitive to climate volatility. The island sits at a crossroads of monsoon systems, bordered by the Indian Ocean and shaped by steep central highlands resting on deeply weathered soils. Its landscapes—especially in plantation regions—have been altered over centuries, reducing natural buffers against hydrological shock. In such a setting, small shifts in atmospheric behaviour can trigger outsized consequences. A few hours of intense rain can undo what months of average rainfall statistics suggest is “normal.”

Nowhere are these consequences more visible than in commercial perennial plantation agriculture. Tea, rubber, coconut, and spice crops are not annual ventures; they are long-term biological investments. A tea bush destroyed by a landslide cannot be replaced in a season. A rubber stand weakened by prolonged waterlogging or drought stress may take years to recover, if it recovers at all. Climate shocks therefore ripple through plantation economics long after floodwaters recede or drought declarations end.

From an investment perspective, this volatility directly undermines key financial metrics. Return on Investment (ROI) becomes unstable as yields fluctuate and recovery costs rise. Benefit–Cost Ratios (BCR) deteriorate when expenditures on drainage, replanting, disease control, and labour increase faster than output. Most critically, Internal Rates of Return (IRR) decline as cash flows become irregular and back-loaded, discouraging long-term capital and raising the cost of financing. Plantation agriculture begins to look less like a stable productive sector and more like a high-risk gamble.

The economic consequences do not stop at balance sheets. Plantation systems are labour-intensive by nature, and when financial margins tighten, wage pressure is the first stress point. Living wage commitments become framed as “unaffordable,” workdays are lost during climate disruptions, and productivity-linked wage models collapse under erratic output. In effect, climate misprediction translates into wage instability, quietly eroding livelihoods without ever appearing in meteorological reports.

This is not an argument for abandoning traditional climate indicators. Rainfall and sunshine still matter. But they are no longer sufficient on their own. Climate today is a system, not a statistic. It is shaped by interactions between the Sun, the atmosphere, the oceans, the land, and the ways humans have modified all three. Ignoring these interactions does not make them disappear; it simply shifts their costs onto farmers, workers, investors, and the public purse.

Sri Lanka’s repeated cycle of surprise disasters, post-event compensation, and stalled reform suggests a deeper problem than bad luck. It points to an outdated model of climate intelligence. Until forecasting frameworks expand beyond local rainfall totals to incorporate broader atmospheric and oceanic drivers—and until those insights are translated into agricultural and economic planning—plantation regions will remain exposed, and wage debates will remain disconnected from their true root causes.

The future of Sri Lanka’s plantations, and the dignity of the workforce that sustains them, depends on a simple shift in perspective: from measuring weather, to understanding systems. Climate is no longer just what falls from the sky. It is what moves through the universe, settles into soils, shapes returns on investment, and ultimately determines whether growth is shared or fragile.

The Way Forward

Sustaining plantation agriculture under today’s climate volatility demands an urgent policy reset. The government must mandate real-world investment appraisals—NPV, IRR, and BCR—through crop research institutes, replacing outdated historical assumptions with current climate, cost, and risk realities. Satellite-based, farm-specific real-time weather stations should be rapidly deployed across plantation regions and integrated with a central server at the Department of Meteorology, enabling precision forecasting, early warnings, and estate-level decision support. Globally proven-to-fail monocropping systems must be phased out through a time-bound transition, replacing them with diversified, mixed-root systems that combine deep-rooted and shallow-rooted species, improving soil structure, water buffering, slope stability, and resilience against prolonged droughts and extreme rainfall.

In parallel, a national plantation insurance framework, linked to green and climate-finance institutions and regulated by the Insurance Regulatory Commission, is essential to protect small and medium perennial growers from systemic climate risk. A Virtual Plantation Bank must be operationalized without delay to finance climate-resilient plantation designs, agroforestry transitions, and productivity gains aligned with national yield targets. The state should set minimum yield and profit benchmarks per hectare, formally recognize 10–50 acre growers as Proprietary Planters, and enable scale through long-term (up to 99-year) leases where state lands are sub-leased to proven operators. Finally, achieving a 4% GDP contribution from plantations requires making modern HRM practices mandatory across the sector, replacing outdated labour systems with people-centric, productivity-linked models that attract, retain, and fairly reward a skilled workforce—because sustainable competitive advantage begins with the right people.

by Dammike Kobbekaduwe

(www.vivonta.lk & www.planters.lk ✍️

Opinion

Disasters do not destroy nations; the refusal to change does

Sri Lanka has endured both kinds of catastrophe that a nation can face, those caused by nature and those created by human hands. A thirty-year civil war tore apart the social fabric, deepening mistrust between communities and leaving lasting psychological wounds, particularly among those who lived through displacement, loss, and fear. The 2004 tsunami, by contrast, arrived without warning, erasing entire coastal communities within minutes and reminding us of our vulnerability to forces beyond human control.

These two disasters posed the same question in different forms: did we learn, and did we change? After the war ended, did we invest seriously in repairing relationships between Sinhalese and Tamil communities, or did we equate peace with silence and infrastructure alone? Were collective efforts made to heal trauma and restore dignity, or were psychological wounds left to be carried privately, generation after generation? After the tsunami, did we fundamentally rethink how and where we build, how we plan settlements, and how we prepare for future risks, or did we rebuild quickly, gratefully, and then forget?

Years later, as Sri Lanka confronts economic collapse and climate-driven disasters, the uncomfortable truth emerges. we survived these catastrophes, but we did not allow them to transform us. Survival became the goal; change was postponed.

History offers rare moments when societies stand at a crossroads, able either to restore what was lost or to reimagine what could be built on stronger foundations. One such moment occurred in Lisbon in 1755. On 1 November 1755, Lisbon-one of the most prosperous cities in the world, was almost completely erased. A massive earthquake, estimated between magnitude 8.5 and 9.0, was followed by a tsunami and raging fires. Churches collapsed during Mass, tens of thousands died, and the royal court was left stunned. Clergy quickly declared the catastrophe a punishment from God, urging repentance rather than reconstruction.

One man refused to accept paralysis as destiny. Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, later known as the Marquês de Pombal, responded with cold clarity. His famous instruction, “Bury the dead and feed the living,” was not heartless; it was revolutionary. While others searched for divine meaning, Pombal focused on human responsibility. Relief efforts were organised immediately, disease was prevented, and plans for rebuilding began almost at once.

Pombal did not seek to restore medieval Lisbon. He saw its narrow streets and crumbling buildings as symbols of an outdated order. Under his leadership, Lisbon was rebuilt with wide avenues, rational urban planning, and some of the world’s earliest earthquake-resistant architecture. Moreover, his vision extended far beyond stone and mortar. He reformed trade, reduced dependence on colonial wealth, encouraged local industries, modernised education, and challenged the long-standing dominance of aristocracy and the Church. Lisbon became a living expression of Enlightenment values, reason, science, and progress.

Back in Sri Lanka, this failure is no longer a matter of opinion. it is documented evidence. An initial assessment by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) following Cyclone Ditwah revealed that more than half of those affected by flooding were already living in households facing multiple vulnerabilities before the cyclone struck, including unstable incomes, high debt, and limited capacity to cope with disasters (UNDP, 2025). The disaster did not create poverty; it magnified it. Physical damage was only the visible layer. Beneath it lay deep social and economic fragility, ensuring that for many communities, recovery would be slow, uneven, and uncertain.

The world today offers Sri Lanka another lesson Lisbon understood centuries ago: risk is systemic, and resilience cannot be improvised, it must be planned. Modern climate science shows that weather systems are deeply interconnected; rising ocean temperatures, changing wind patterns, and global emissions influence extreme weather far beyond their points of origin. Floods, landslides, and cyclones affecting Sri Lanka are no longer isolated events, but part of a broader climatic shift. Rebuilding without adapting construction methods, land-use planning, and infrastructure to these realities is not resilience, it is denial. In this context, resilience also depends on Sri Lanka’s willingness to learn from other countries, adopt proven technologies, and collaborate across borders, recognising that effective solutions to global risks cannot be developed in isolation.

A deeper problem is how we respond to disasters: we often explain destruction without seriously asking why it happened or how it could have been prevented. Time and again, devastation is framed through religion, fate, karma, or divine will. While faith can bring comfort in moments of loss, it cannot replace responsibility, foresight, or reform. After major disasters, public attention often focuses on stories of isolated religious statues or buildings that remain undamaged, interpreted as signs of protection or blessing, while far less attention is paid to understanding environmental exposure, construction quality, and settlement planning, the factors that determine survival. Similarly, when a single house survives a landslide, it is often described as a miracle rather than an opportunity to study soil conditions, building practices, and land-use decisions. While such interpretations may provide emotional reassurance, they risk obscuring the scientific understanding needed to reduce future loss.

The lesson from Lisbon is clear: rebuilding a nation requires the courage to question tradition, the discipline to act rationally, and leadership willing to choose long-term progress over short-term comfort. Until Sri Lanka learns to rebuild not only roads and buildings, but relationships, institutions, and ways of thinking, we will remain a country trapped in recovery, never truly reborn.

by Darshika Thejani Bulathwatta

Psychologist and Researcher

Opinion

A wise Christmas

Important events in the Christian calendar are to be regurlarly reviewed if they are to impact on the lives of people and communities. This is certainly true of Christmas.

Community integrity

Years ago a modest rural community did exactly this, urging a pre-Christmas probe of the events around Jesus’ birth. From the outset, the wisemen aroused curiosity. Who were these visitors? Were they Jews? No. were they Christians? Of course not. As they probed the text, the representative character of those around the baby, became starkly clear. Apart from family, the local shepherds and the stabled animals, the only others present that first Christmas, were sages from distant religious cultures.

With time, the celebration of Christmas saw a sharp reversal. The church claimed exclusive ownership of an inclusive gift and deftly excluded ‘outsiders’ from full participation.

But the Biblical version of the ‘wise outsiders’ remained. It affirmed that the birth of Jesus inspired the wise to initiate a meeting space for diverse religious cultures, notwithstanding the long and ardous journey such initiatives entail. Far from exclusion, Jesus’ birth narratives, announced the real presence of the ‘outsider’ when the ‘Word became Flesh’.

The wise recognise the gift of life as an invitation to integrate sincere explanations of life; true religion. Religion gone bad, stalls these values and distorts history.

There is more to the visit of these sages.

Empire- When Jesus was born, Palestine was forcefully occcupied by the Roman empire. Then as now, empire did not take kindly to other persons or forces that promised dignity and well being. So, when rumours of a coming Kingdom of truth, justice and peace, associated with the new born baby reached the local empire agent, a self appointed king; he had to deliver. Information on the wherabouts of the baby would be diplomatically gleaned from the visiting sages.

But the sages did not only read the stars. They also read the signs of the times. Unlike the local religious authorities who cultivated dubious relations with a brutal regime hated by the people, the wise outsiders by-pass the waiting king.

The boycott of empire; refusal to co-operate with those who take what it wills, eliminate those it dislikes and dare those bullied to retaliate, is characteristic of the wise.

Gifts of the earth

A largely unanswered question has to do with the gifts offered by the wise. What happened to these gifts of the earth? Silent records allow context and reason to speak.

News of impending threats to the most vulnerable in the family received the urgent attention of his anxious parent-carers. Then as it is now, chances of survival under oppressive regimes, lay beyond borders. As if by anticipation, resources for the journey for asylum in neighbouring Egypt, had been provided by the wise. The parent-carers quietly out smart empire and save the saviour to be.

Wise carers consider the gifts of the earth as resources for life; its protection and nourishment. But, when plundered and hoarded, resources for all, become ‘wealth’ for a few; a condition that attempts to own the seas and the stars.

Wise choices

A wise christmas requires that the sages be brought into the centre of the discourse. This is how it was meant to be. These visitors did not turn up by chance. They were sent by the wisdom of the ages to highlight wise choices.

At the centre, the sages facilitate a preview of the prophetic wisdom of the man the baby becomes.The choice to appropriate this prophetic wisdom has ever since summed up Christmas for those unable to remain neutral when neighbour and nature are violated.

Wise carers

The wisdom of the sages also throws light on the life of our nation, hard pressed by the dual crises of debt repayment and post cyclonic reconstruction. In such unrelenting circumstances, those in civil governance take on an additional role as national carers.

The most humane priority of the national carer is to ensure the protection and dignity of the most vulnerable among us, immersed in crisis before the crises. Better opportunities, monitored and sustained through conversations are to gradually enhance the humanity of these equal citizens.

Nations in economic crises are nevertheless compelled to turn to global organisations like the IMF for direction and reconstruction. Since most who have been there, seldom stand on their own feet, wise national carers may not approach the negotiating table, uncritically. The suspicion, that such organisations eventually ‘grow’ ailing nations into feeder forces for empire economics, is not unfounded.

The recent cyclone gave us a nasty taste of these realities. Repeatedly declared a natural disaster, this is not the whole truth. Empire economics which indiscriminately vandalise our earth, had already set the stage for the ravage of our land and the loss of loved ones and possessions. As always, those affected first and most, were the least among us.

Unless we learn to manouvre our dealings for recovery wisely; mindful of our responsibilities by those relegated to the margins as well as the relentles violence and greed of empire, we are likely to end up drafted collaborators of the relentless havoc against neighbour and nature.

If on the other hand the recent and previous disasters are properly assessed by competent persons, reconstruction will be seen as yet another opportunity for stabilising content and integrated life styles for all Lankans, in some harmony with what is left of our dangerously threatened eco-system. We might then even stand up to empire and its wily agents, present everywhere. Who knows?

With peace and blessings to all!

Bishop Duleep de Chickera

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoBritish MP calls on Foreign Secretary to expand sanction package against ‘Sri Lankan war criminals’

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoAir quality deteriorating in Sri Lanka

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCardinal urges govt. not to weaken key socio-cultural institutions

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoGeneral education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoSuspension of Indian drug part of cover-up by NMRA: Academy of Health Professionals

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCID probes unauthorised access to PNB’s vessel monitoring system

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoRanwala crash: Govt. lays bare its true face