Features

MY FIRST OVERSEAS BUSINESS VISIT

Excerpted from the autobiography of Merril. J. Fernando

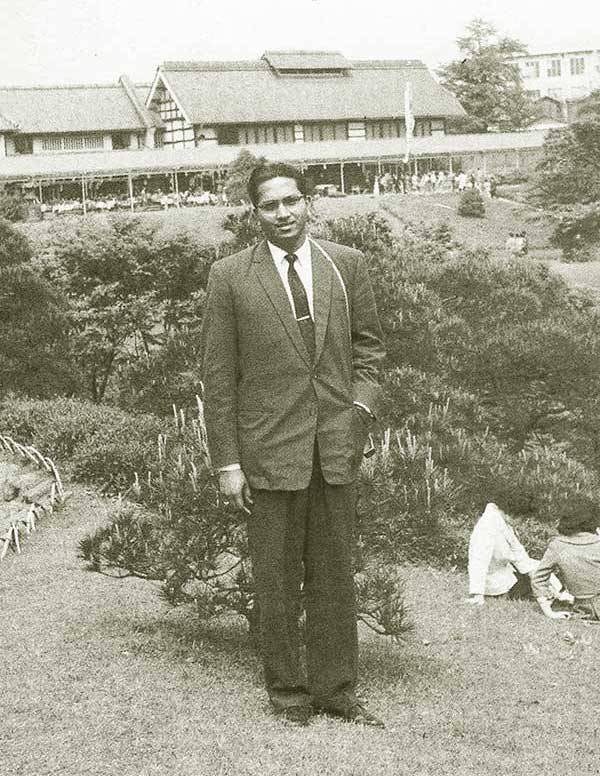

Before I set out for Jap1an, in 1960, on my first overseas business trip, I was advised by Terrence Allan of AF Jones to be extremely careful in the manner that I dealt with our agents in Japan, H. J. Kramer Limited, a Japanese company headed by Otto Gerhardt, a German national. Apparently, Gerhardt had been very apprehensive when he heard that I was due to visit him, as, previously, he had had only British Directors of the company on business visits.

He had been very concerned for his business and the interviews we had arranged. He did not know me personally and may have been very doubtful of my competence, whilst the fact that I was an unknown and unproven Asian would have also contributed significantly to his misgivings.

My first official meeting in Japan was with our biggest importer, Mitsui Norin. Two of its Directors, Messrs. Evakura and Saito, invited me to a tasting session – much to the surprise of Gerhardt. He was very nervous about the possible outcome, as if I did anything to displease or disappoint the Japanese clients, there was the possibility of losing a very good customer.

I started tasting the teas which had been set out and, at one point, came to a very zippy tea, much like a very good Darjeeling. When my hosts asked me about the identity of the tea, quite naturally I said that it was a Darjeeling but they disagreed and said that it was a Japanese tea. I responded that it could not be since in Japan they produced only Green Tea, Sencha, as I was unaware then that Japan produced quality Black Tea.

After the tasting session Otto told our Japanese hosts that he was taking me to Atami because I wanted to see Mount Fuji and, jokingly, invited them to join. To his very pleasant surprise, they welcomed the idea and accompanied us. Atami is a picturesque seaside resort, south west of Tokyo, set within the Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park and also the home to Mount Fuji. On our way to Fuji we broke journey and checked into a traditional Japanese hotel in Atami itself. I was shown to a rather bare room which had a clothes cupboard but no bed. When I inquired I was told that a bed would be provided.

Japanese hospitality

Soon afterwards a traditionally-dressed Japanese lady came into my room, undressed me completely, and took me into a Japanese-style bathing stall. I sat on a large cane box whilst she poured soothing warm water over me. Thereafter, I was led back in to the bedroom which, by then, had been equipped, not with a conventional bed but a Japanese-style sleeping mattress and comfortable sheets.

The dinner which followed was again of delicately-prepared Japanese dishes and local wine. Right through the meal we were attended to by Geisha type hostesses, who sat demurely by each guest’s side and, unobtrusively, but with perfect timing, anticipated our minutest needs. After two very pleasant and adventurous days, we returned to Tokyo to resume our business discussions.

To Otto’s surprise and apprehension, Evakura and Saito invited me to their office for another tea tasting session. When I arrived I was confronted with a batch of teas, which included the same Japanese equivalent of Darjeeling tea. After tasting the samples, when I identified those teas as Japanese, my hosts contradicted me and said that it was Darjeeling, despite my repeated insistence to the contrary. Notwithstanding this disagreement, the visit ended very well. I am still convinced that I was right and they were simply testing my competence as a taster. Had they been disappointed, I am certain that they would have made it known in some way.

Consequent to my visit, our business with Japan increased fourfold — much to the annoyance of Lipton, then the major supplier to Japan. In fact, Claude Godwin, Lipton’s then Managing Director, asked me not to visit Japan ever again. Indeed, my first business visit overseas on behalf of A. F. Jones resulted in very satisfactory outcomes for the company. Following the visit to Japan, at different times, I made several visits on behalf of A. F. Jones to Libya and Iraq, two of our most productive markets in that period.

My success at A. F. Jones and Co. Limited, which was appreciated by my employer, was due to both good fortune and extremely hard work. I was personally deeply satisfied by the favourable results I was able to secure, despite the fact that many aspects of the relevant operations were quite new to me.

Opening of the USSR market

The General Election of 1956, which swept out the United National Party (UNP) and brought in the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna (MEP) coalition forces led by S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, soon had its impact on international relations between Sri Lanka and the rest of the world. The anti-imperialist orientation of Premier Bandaranaike’s regime encouraged stronger ties with Marxist governments and, in December 1958, during my time at A. F. Jones, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR – Russia) established its first Embassy in Ceylon.

This development was a consequence of formal diplomatic relations between the two countries being established in 1957. Subsequently, the many bilateral agreements signed between the two countries included the export of tea, rubber, coconut oil, and coir products. These agreements were renewed and updated in 1964, 1975, and 1977.

Traditionally, Russians were big tea drinkers, with imports being largely Black Tea from China. The first consignments of Ceylon Tea had reached Russia in the 1890s, with exports from Ceylon going up to about 18 million pounds annually by 1910. However, this was minimalistic in comparison to imports from China, which then were around 120 million pounds. After trade relations were disrupted consequent to the 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Russia, there was a four-decade lull in trading activity with Ceylon.

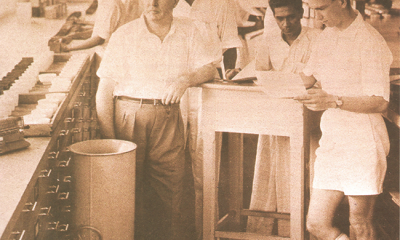

The first USSR Ambassador to Ceylon, Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev, was introduced to me by a mutual friend. Yakovlev was a friendly man and got on well with us. He requested me to help his Trade Counsellor, Felix I. Mikailchenkov, to set up a tea tasting facility in a house on Thurstan Road leased out by them for that purpose. When it was completed in mid-1958, Felix said: “I am entrusting you with the responsibility of purchasing our entire requirements of Ceylon Tea.” I did not realize how big the business would be until their orders arrived.

They turned out to be quite substantial, around three to four million kg per month, mainly of good High Grown BOPS and Pekoes. In view of the volume of tea involved, many of the larger firms operating in Colombo attempted to secure the purchasing, but the relationship I had already established with the Russian representatives stood me, and A. F. Jones, in good stead.

That rapid and unexpected increase in Russian buying had a significant impact on the auction, as our large purchases of High Grown tea became a regular feature. It resulted in A. F. Jones becoming the sole buyer on behalf of Russia and a big player at the auction. The Jones family was very grateful for my contribution to this welcome business development and presented me with a silver plaque, inscribed with the legend ‘MOCKBA — December 8, 1958’. It is still displayed prominently in my office at Peliyagoda.

Until the sudden development of the Russian market, the bulk of the AFJ business centred on the Middle East, with strong attachments in Libya, Iraq, and Iran. Whenever a Russian ship arrived in port to collect their tea, which was often at short notice, there would be a major crisis in our office. We used to start processing just prior to arrival of the vessels, as the tea chests arriving from the estates were not opened but shipped out in bulk, in their original form.

However, four sides of each chest had to be marked with Russian text, defining the various Russian brands under which the product would be sold in Russia. Senior Managers at the Port, especially C. D. Chinnakoon, were of great assistance to me in such emergency situations. He would buy me time by holding ships in the outer harbour, pending berthing, and somehow providing berths when we were ready with our consignment.

Our Colombo Harbour then had limited alongside berthing facilities. Chinnakoon was a great friend and I always kept in touch with him. Unfortunately, he had an untimely death and I pray that he is in the hands of God.

We serviced the Russian market until the Sri Lankan Government entered in to a direct agreement with the Russian administration, and the tea buying was entrusted to Consolexpo.The Russian rubber business was carried out by C. W. Mackie under the supervision of Karu Jayasuriya, business manager now turned politician.

My Russian connections

Yakovlev, a senior Russian diplomat even at the time he arrived in Ceylon, became well known in the country for his very effective interaction with his Ceylonese counterparts, whilst his tireless promotion of USSR interests within the country, apart from tea, earned him many friends in the business community. On conclusion of his term in Ceylon he returned to the Foreign Ministry in Moscow. He subsequently served a 10-year term (1973-1983) as Russia’s Ambassador to Canada.

He was a very powerful party official in Russia, apparently very close to Prime Minister Mikhail Gorbachev. After his return from Canada on completion of his ambassadorial assignment, he served for several years as a member of both the Politburo and the Secretariat of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He is identified as the primary intellectual force behind ‘Glasnost’ and `Perestroika,’ highly influential in guiding Gorbachev’s hand in the latter’s political reform initiatives.

In ‘Gorbachev’ by William Taubman, possibly the most comprehensive original English biography of the architect of Perestroika, the author refers to Yakovlev as Gorbachev’s closest ally in Government. Until his death in 2005, Yakovlev remained politically very active and was also the author of several books, on diverse aspects of Russian contemporary political history.

In 1970, Yakovlev was replaced in Ceylon by Rafiq Nishonov, again a friendly, warm-hearted man. Eventually, both he and Rano, his gracious and friendly wife, became our family friends. One of his daughters, Firouza, was actually born during his term in Sri Lanka and together, they would frequently accompany me for holidays at my upcountry retreat, Melton Estate, in Lindula.

Rafiq, of Uzbek origin, served as Russian Ambassador in Sri Lanka from 1970-1978. During his period our tea export operations, supported by generous Russian patronage, grew considerably. Rafiq was always helpful to the local tea trading community, but ensured that his country’s interests were never compromised. Consequent to his return to USSR, he became heavily involved in party activities in his native Uzbekistan and between 1986 and 1989, served terms as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic and also, as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Uzbek SSR.

I later learnt from him that he had been actively involved in assisting then Prime Minister Gorbachev, whom he was very close to, in resolving some tricky issues connected to the Russian entanglement in Afghanistan. I also understood that they were covert operations, deliberately withheld from the public domain.

On many visits to Moscow, I had several meetings with both Rafiq and his wife. Several times I was taken to his holiday ‘dacha’ in the country and also to the special hospital reserved for senior parliamentarians when I needed any medical attention. He also introduced me to several important Government officials, including the present Foreign Minister of Russia, Sergei Lavrov, who served in Ceylon during Rafiq’s tenure as Ambassador. In fact, during Rafiq’s term as Ambassador in Ceylon, because of Lavrov’s fluent command of Sinhala, he also served as Rafiq’s interpreter on official occasions.

Rafiq’s Deputy at the USSR Embassy was the big, powerfully-built Sasha Lysenko, a man of considerable influence in local diplomatic circles. Our business association developed in to personal friendship as well, and he and his wife became great friends with me. My close interaction with Russian diplomatic and trade representatives in Sri Lanka, provided me with highly-beneficial access to their counterparts and associates in Moscow. These contacts and relationships built up over the years were of great help to me subsequently in the development of my Dilmah brand.

I made my first business visit to Russia in 1962. Most of the Russian officials serving in various capacities in Sri Lanka, who I met in the course of my business, also became great personal friends. Without exception, I found them to be warm and friendly, naturally gregarious and, as a group, with a great capacity for enjoyment. Most of the Russians I met, both in Sri Lanka and in their home country, were, by and large, Asiatic in their unaffected friendliness and camaraderie, though they did take time to measure you. Once the ice was broken, they took you into their hearts and their homes. The difference between them and the typical Westerners, with their more restrained and often-guarded responses, was easily discernible.

Features

Rebuilding Sri Lanka Through Inclusive Governance

In the immediate aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah, the government has moved swiftly to establish a Presidential Task Force for Rebuilding Sri Lanka with a core committee to assess requirements, set priorities, allocate resources and raise and disburse funds. Public reaction, however, has focused on the committee’s problematic composition. All eleven committee members are men, and all non-government seats are held by business personalities with no known expertise in complex national development projects, disaster management and addressing the needs of vulnerable populations. They belong to the top echelon of Sri Lanka’s private sector which has been making extraordinary profits. The government has been urged by civil society groups to reconsider the role and purpose of this task force and reconstitute it to be more representative of the country and its multiple needs.

The group of high-powered businessmen initially appointed might greatly help mobilise funds from corporates and international donors, but this group may be ill equipped to determine priorities and oversee disbursement and spending. It would be necessary to separate fundraising, fund oversight and spending prioritisation, given the different capabilities and considerations required for each. International experience in post disaster recovery shows that inclusive and representative structures are more likely to produce outcomes that are equitable, efficient and publicly accepted. Civil society, for instance, brings knowledge rooted in communities, experience in working with vulnerable groups and a capacity to question assumptions that may otherwise go unchallenged.

A positive and important development is that the government has been responsive to these criticisms and has invited at least one civil society representative to join the Rebuilding Sri Lanka committee. This decision deserves to be taken seriously and responded to positively by civil society which needs to call for more representation rather than a single representative. Such a demand would reflect an understanding that rebuilding after a national disaster cannot be undertaken by the state and the business community alone. The inclusion of civil society will strengthen transparency and public confidence, particularly at a moment when trust in institutions remains fragile. While one appointment does not in itself ensure inclusive governance, it opens the door to a more participatory approach that needs to be expanded and institutionalised.

Costly Exclusions

Going down the road of history, the absence of inclusion in government policymaking has cost the country dearly. The exclusion of others, not of one’s own community or political party, started at the very dawn of Independence in 1948. The Father of the Nation, D S Senanayake, led his government to exclude the Malaiyaha Tamil community by depriving them of their citizenship rights. Eight years later, in 1956, the Oxford educated S W R D Bandaranaike effectively excluded the Tamil speaking people from the government by making Sinhala the sole official language. These early decisions normalised exclusion as a tool of governance rather than accommodation and paved the way for seven decades of political conflict and three decades of internal war.

Exclusion has also taken place virulently on a political party basis. Both of Sri Lanka’s post Independence constitutions were decided on by the government alone. The opposition political parties voted against the new constitutions of 1972 and 1977 because they had been excluded from participating in their design. The proposals they had made were not accepted. The basic law of the country was never forged by consensus. This legacy continues to shape adversarial politics and institutional fragility. The exclusion of other communities and political parties from decision making has led to frequent reversals of government policy. Whether in education or economic regulation or foreign policy, what one government has done the successor government has undone.

Sri Lanka’s poor performance in securing the foreign investment necessary for rapid economic growth can be attributed to this factor in the main. Policy instability is not simply an economic problem but a political one rooted in narrow ownership of power. In 2022, when the people went on to the streets to protest against the government and caused it to fall, they demanded system change in which their primary focus was corruption, which had reached very high levels both literally and figuratively. The focus on corruption, as being done by the government at present, has two beneficial impacts for the government. The first is that it ensures that a minimum of resources will be wasted so that the maximum may be used for the people’s welfare.

Second Benefit

The second benefit is that by focusing on the crime of corruption, the government can disable many leaders in the opposition. The more opposition leaders who are behind bars on charges of corruption, the less competition the government faces. Yet these gains do not substitute for the deeper requirement of inclusive governance. The present government seems to have identified corruption as the problem it will emphasise. However, reducing or eliminating corruption by itself is not going to lead to rapid economic development. Corruption is not the sole reason for the absence of economic growth. The most important factor in rapid economic growth is to have government policies that are not reversed every time a new government comes to power.

For Sri Lanka to make the transition to self-sustaining and rapid economic development, it is necessary that the economic policies followed today are not reversed tomorrow. The best way to ensure continuity of policy is to be inclusive in governance. Instead of excluding those in the opposition, the mainstream opposition in particular needs to be included. In terms of system change, the government has scored high with regard to corruption. There is a general feeling that corruption in the country is much reduced compared to the past. However, with regard to inclusion the government needs to demonstrate more commitment. This was evident in the initial choice of cabinet ministers, who were nearly all men from the majority ethnic community. Important committees it formed, including the Presidential Task Force for a Clean Sri Lanka and the Rebuilding Sri Lanka Task Force, also failed at first to reflect the diversity of the country.

In a multi ethnic and multi religious society like Sri Lanka, inclusivity is not merely symbolic. It is essential for addressing diverse perspectives and fostering mutual understanding. It is important to have members of the Tamil, Muslim and other minority communities, and women who are 52 percent of the population, appointed to important decision making bodies, especially those tasked with national recovery. Without such representation, the risk is that the very communities most affected by the crisis will remain unheard, and old grievances will be reproduced in new forms. The invitation extended to civil society to participate in the Rebuilding Sri Lanka Task Force is an important beginning. Whether it becomes a turning point will depend on whether the government chooses to make inclusion a principle of governance rather than treat it as a show of concession made under pressure.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Reservoir operation and flooding

Former Director General of Irrigation, G.T. Dharmasena, in an article, titled “Revival of Innovative systems for reservoir operation and flood forecasting” in The Island of 17 December, 2025, starts out by stating:

“Most reservoirs in Sri Lanka are agriculture and hydropower dominated. Reservoir operators are often unwilling to acknowledge the flood detention capability of major reservoirs during the onset of monsoons. Deviating from the traditional priority for food production and hydropower development, it is time to reorient the operational approach of major reservoirs operators under extreme events, where flood control becomes a vital function. While admitting that total elimination of flood impacts is not technically feasible, the impacts can be reduced by efficient operation of reservoirs and effective early warning systems”.

Addressing the question often raised by the public as to “Why is flooding more prominent downstream of reservoirs compared to the period before they were built,” Mr. Dharmasena cites the following instances: “For instance, why do (sic) Magama in Tissamaharama face floods threats after the construction of the massive Kirindi Oya reservoir? Similarly, why does Ambalantota flood after the construction of Udawalawe Reservoir? Furthermore, why is Molkawa, in the Kalutara District area, getting flooded so often after the construction of Kukule reservoir”?

“These situations exist in several other river basins, too. Engineers must, therefore, be mindful of the need to strictly control the operation of the reservoir gates by their field staff. (Since) “The actual field situation can sometimes deviate significantly from the theoretical technology… it is necessary to examine whether gate operators are strictly adhering to the operational guidelines, as gate operation currently relies too much on the discretion of the operator at the site”.

COMMENT

For Mr. Dharmasena to bring to the attention of the public that “gate operation currently relies too much on the discretion of the operator at the site”, is being disingenuous, after accepting flooding as a way of life for ALL major reservoirs for decades and not doing much about it. As far as the public is concerned, their expectation is that the Institution responsible for Reservoir Management should, not only develop the necessary guidelines to address flooding but also ensure that they are strictly administered by those responsible, without leaving it to the arbitrary discretion of field staff. This exercise should be reviewed annually after each monsoon, if lives are to be saved and livelihoods are to be sustained.

IMPACT of GATE OPERATION on FLOODING

According to Mr. Dhamasena, “Major reservoir spillways are designed for very high return periods… If the spillway gates are opened fully when reservoir is at full capacity, this can produce an artificial flood of a very large magnitude… Therefore, reservoir operators must be mindful in this regard to avoid any artificial flood creation” (Ibid). Continuing, he states: “In reality reservoir spillways are often designed for the sole safety of the reservoir structure, often compromising the safety of the downstream population. This design concept was promoted by foreign agencies in recent times to safeguard their investment for dams. Consequently, the discharge capacities of these spill gates significantly exceed the natural carrying capacity of river(s) downstream” (Ibid).

COMMENT

The design concept where priority is given to the “sole safety of the structure” that causes the discharge capacity of spill gates to “significantly exceed” the carrying capacity of the river is not limited to foreign agencies. Such concepts are also adopted by local designers as well, judging from the fact that flooding is accepted as an inevitable feature of reservoirs. Since design concepts in their current form lack concern for serious destructive consequences downstream and, therefore, unacceptable, it is imperative that the Government mandates that current design criteria are revisited as a critical part of the restoration programme.

CONNECTIVITY BETWEEN GATE OPENINGS and SAFETY MEASURES

It is only after the devastation of historic proportions left behind by Cyclone Ditwah that the Public is aware that major reservoirs are designed with spill gate openings to protect the safety of the structure without factoring in the consequences downstream, such as the safety of the population is an unacceptable proposition. The Institution or Institutions associated with the design have a responsibility not only to inform but also work together with Institutions such as Disaster Management and any others responsible for the consequences downstream, so that they could prepare for what is to follow.

Without working in isolation and without limiting it only to, informing related Institutions, the need is for Institutions that design reservoirs to work as a team with Forecasting and Disaster Management and develop operational frameworks that should be institutionalised and approved by the Cabinet of Ministers. The need is to recognize that without connectivity between spill gate openings and safety measures downstream, catastrophes downstream are bound to recur.

Therefore, the mandate for dam designers and those responsible for disaster management and forecasting should be for them to jointly establish guidelines relating to what safety measures are to be adopted for varying degrees of spill gate openings. For instance, the carrying capacity of the river should relate with a specific openinig of the spill gate. Another specific opening is required when the population should be compelled to move to high ground. The process should continue until the spill gate opening is such that it warrants the population to be evacuated. This relationship could also be established by relating the spill gate openings to the width of the river downstream.

The measures recommended above should be backed up by the judicious use of the land within the flood plain of reservoirs for “DRY DAMS” with sufficient capacity to intercept part of the spill gate discharge from which excess water could be released within the carrying capacity of the river. By relating the capacity of the DRY DAM to the spill gate opening, a degree of safety could be established. However, since the practice of demarcating flood plains is not taken seriously by the Institution concerned, the Government should introduce a Bill that such demarcations are made mandatory as part of State Land in the design and operation of reservoirs. Adopting such a practice would not only contribute significantly to control flooding, but also save lives by not permitting settlement but permitting agricultural activities only within these zones. Furthermore, the creation of an intermediate zone to contain excess flood waters would not tax the safety measures to the extent it would in the absence of such a safety net.

CONCLUSION

Perhaps, the towns of Kotmale and Gampola suffered severe flooding and loss of life because the opening of spill gates to release the unprecedented volumes of water from Cyclone Ditwah, was warranted by the need to ensure the safety of Kotmale and Upper Kotmale Dams.

This and other similar disasters bring into focus the connectivity that exists between forecasting, operation of spill gates, flooding and disaster management. Therefore, it is imperative that the government introduce the much-needed legislative and executive measures to ensure that the agencies associated with these disciplines develop a common operational framework to mitigate flooding and its destructive consequences. A critical feature of such a framework should be the demarcation of the flood plain, and decree that land within the flood plain is a zone set aside for DRY DAMS, planted with trees and free of human settlements, other than for agricultural purposes. In addition, the mandate of such a framework should establish for each river basin the relationship between the degree to which spill gates are opened with levels of flooding and appropriate safety measures.

The government should insist that associated Agencies identify and conduct a pilot project to ascertain the efficacy of the recommendations cited above and if need be, modify it accordingly, so that downstream physical features that are unique to each river basin are taken into account and made an integral feature of reservoir design. Even if such restrictions downstream limit the capacities to store spill gate discharges, it has to be appreciated that providing such facilities within the flood plain to any degree would mitigate the destructive consequences of the flooding.

By Neville Ladduwahetty

Features

Listening to the Language of Shells

The ocean rarely raises its voice. Instead, it leaves behind signs — subtle, intricate and enduring — for those willing to observe closely. Along Sri Lanka’s shores, these signs often appear in the form of seashells: spiralled, ridged, polished by waves, carrying within them the quiet history of marine life. For Marine Naturalist Dr. Malik Fernando, these shells are not souvenirs of the sea but storytellers, bearing witness to ecological change, resilience and loss.

“Seashells are among the most eloquent narrators of the ocean’s condition,” Dr. Fernando told The Island. “They are biological archives. If you know how to read them, they reveal the story of our seas, past and present.”

A long-standing marine conservationist and a member of the Marine Subcommittee of the Wildlife & Nature Protection Society (WNPS), Dr. Fernando has dedicated much of his life to understanding and protecting Sri Lanka’s marine ecosystems. While charismatic megafauna often dominate conservation discourse, he has consistently drawn attention to less celebrated but equally vital marine organisms — particularly molluscs, whose shells are integral to coastal and reef ecosystems.

“Shells are often admired for their beauty, but rarely for their function,” he said. “They are homes, shields and structural components of marine habitats. When shell-bearing organisms decline, it destabilises entire food webs.”

Sri Lanka’s geographical identity as an island nation, Dr. Fernando says, is paradoxically underrepresented in national conservation priorities. “We speak passionately about forests and wildlife on land, but our relationship with the ocean remains largely extractive,” he noted. “We fish, mine sand, build along the coast and pollute, yet fail to pause and ask how much the sea can endure.”

Through his work with the WNPS Marine Subcommittee, Dr. Fernando has been at the forefront of advocating for science-led marine policy and integrated coastal management. He stressed that fragmented governance and weak enforcement continue to undermine marine protection efforts. “The ocean does not recognise administrative boundaries,” he said. “But unfortunately, our policies often do.”

He believes that one of the greatest challenges facing marine conservation in Sri Lanka is invisibility. “What happens underwater is out of sight, and therefore out of mind,” he said. “Coral bleaching, mollusc depletion, habitat destruction — these crises unfold silently. By the time the impacts reach the shore, it is often too late.”

Seashells, in this context, become messengers. Changes in shell thickness, size and abundance, Dr. Fernando explained, can signal shifts in ocean chemistry, rising temperatures and increasing acidity — all linked to climate change. “Ocean acidification weakens shells,” he said. “It is a chemical reality with biological consequences. When shells grow thinner, organisms become more vulnerable, and ecosystems less stable.”

Seashells, in this context, become messengers. Changes in shell thickness, size and abundance, Dr. Fernando explained, can signal shifts in ocean chemistry, rising temperatures and increasing acidity — all linked to climate change. “Ocean acidification weakens shells,” he said. “It is a chemical reality with biological consequences. When shells grow thinner, organisms become more vulnerable, and ecosystems less stable.”

Climate change, he warned, is no longer a distant threat but an active force reshaping Sri Lanka’s marine environment. “We are already witnessing altered breeding cycles, migration patterns and species distribution,” he said. “Marine life is responding rapidly. The question is whether humans will respond wisely.”

Despite the gravity of these challenges, Dr. Fernando remains an advocate of hope rooted in knowledge. He believes public awareness and education are essential to reversing marine degradation. “You cannot expect people to protect what they do not understand,” he said. “Marine literacy must begin early — in schools, communities and through public storytelling.”

It is this belief that has driven his involvement in initiatives that use visual narratives to communicate marine science to broader audiences. According to Dr. Fernando, imagery, art and heritage-based storytelling can evoke emotional connections that data alone cannot. “A well-composed image of a shell can inspire curiosity,” he said. “Curiosity leads to respect, and respect to protection.”

Shells, he added, also hold cultural and historical significance in Sri Lanka, having been used for ornamentation, ritual objects and trade for centuries. “They connect nature and culture,” he said. “By celebrating shells, we are also honouring coastal communities whose lives have long been intertwined with the sea.”

However, Dr. Fernando cautioned against romanticising the ocean without acknowledging responsibility. “Celebration must go hand in hand with conservation,” he said. “Otherwise, we risk turning heritage into exploitation.”

He was particularly critical of unregulated shell collection and commercialisation. “What seems harmless — picking up shells — can have cumulative impacts,” he said. “When multiplied across thousands of visitors, it becomes extraction.”

As Sri Lanka continues to promote coastal tourism, Dr. Fernando emphasised the need for sustainability frameworks that prioritise ecosystem health. “Tourism must not come at the cost of the very environments it depends on,” he said. “Marine conservation is not anti-development; it is pro-future.”

Dr. Malik Fernando

Reflecting on his decades-long engagement with the sea, Dr. Fernando described marine conservation as both a scientific pursuit and a moral obligation. “The ocean has given us food, livelihoods, climate regulation and beauty,” he said. “Protecting it is not an act of charity; it is an act of responsibility.”

He called for stronger collaboration between scientists, policymakers, civil society and the private sector. “No single entity can safeguard the ocean alone,” he said. “Conservation requires collective stewardship.”

Yet, amid concern, Dr. Fernando expressed cautious optimism. “Sri Lanka still has immense marine wealth,” he said. “Our reefs, seagrass beds and coastal waters are resilient, if given a chance.”

Standing at the edge of the sea, shells scattered along the sand, one is reminded that the ocean does not shout its warnings. It leaves behind clues — delicate, enduring, easily overlooked. For Dr. Malik Fernando, those clues demand attention.

“The sea is constantly communicating,” he said. “In shells, in currents, in changing patterns of life. The real question is whether we, as a society, are finally prepared to listen — and to act before silence replaces the story.”

By Ifham Nizam

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoBritish MP calls on Foreign Secretary to expand sanction package against ‘Sri Lankan war criminals’

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoChief selector’s remarks disappointing says Mickey Arthur

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoDisasters do not destroy nations; the refusal to change does

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSri Lanka’s coastline faces unfolding catastrophe: Expert

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoLankan aircrew fly daring UN Medevac in hostile conditions in Africa

-

Midweek Review6 days ago

Midweek Review6 days agoYear ends with the NPP govt. on the back foot

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoLife after the armband for Asalanka