Features

Events leading to the signing of the Indo-Lanka Agreement

JR tells Rajiv “We can forgive but we cannot forget”

(Excerpted from volume ii of the Amunugama autobiography)

It was at this dismal stage that a new development in the long drawn out negotiations emerged. Due to his cricketing contacts Gamini became close to N Ram of the Kasturi family controlling `The Hindu’ newspaper which though originating in Madras had an all-India coverage with a strong presence in New Delhi. This was later seen when ‘The Hindu’ destabilized the Rajiv regime with their ‘scoop’ on the Bofors scandal.

The Kasturis were Brahmins who were on top of the South Indian social register. In their background correspondence Ram and Gamini had the concurrence of Rajiv Gandhi, if not of the Indian foreign policy establishment. It is said in JRJ’s biography by Wriggins and De Silva that at this stage the LTTE through back channels had indicated that they were in favour of an agreement if the Northern and Eastern provinces were joined. A new element of an Indian guarantee of an enforcement of an agreement between the two parties now entered the scene.

As Bernard Tillekeratne has written “Ram’s letter of 12th June 198 7….. outlined a set of proposals on the important precondition that India would be the mediator in all the discussions and even more importantly that it would underwrite the implementation of any agreement reached. This letter was one of the first positive developments that culminated in the Indo-Lanka Accord of 29th July 1987”.

Regarding the allocation of powers to the Provincial Councils JRJ cut the Gordian knot by suggesting that we adopt ‘in toto’ the provisions of the Indian constitution regarding the devolution of powers to the States. Thus, there would be three lists as in India – the powers of the Centre, the powers of the Provincial Councils and a concurrent list in which certain powers were exercised by both the centre and the periphery.

Earlier the discussion centered on devolution only to the North-Eastern Provincial Council. JRJ decided that all areas in the country should be brought under the second tier scheme. Once this formula was accepted the difficult task of ‘selling’ it to the Sinhala and LTTE protagonists were undertaken by the two parties. The Indian operation was undertaken by Dixit and his political secretary in Colombo. After his deputy met Prabhakaran and his advisors in the Vanni several times, though it was later disputed by the LTTE, Dixit informed New Delhi that he had succeeded in persuading the LTTE leaders to lay down their arms once the agreement was signed.

JRJ was for the immediate signing of the accord as he knew that opposition would build up not only from the SLFP and JVP but also from factions within his own Government. It became clear that Premadasa was against such an agreement and was being set up as a virulent opponent of India with Athulathmudali’s encouragement. Once I was asked to bring some documents to the Cabinet room while Cabinet sessions were in progress. As I climbed up the stairs I ran into Prime Minister Premadasa rushing down the steps in anger. However there was no one following him to cool him down as they usually do in those Cabinet dramas.

Gamani Jayasuriya who represented the Sinhala Buddhist lobby resigned in protest. During this time I associated with Gamani Jayasuriya as we were both members of the Governing Council of CNAPT (Ceylon National Association for the Prevention of Tubercolosis)in which my friend of University days, Fonseka, was secretary. Fonseka, who was a well-known astrologer, had predicted that Gamani would be the Prime Minister when this fracas was over. After resigning Gamani would visit Fonseka almost daily to check whether his prediction was coming true. In the event it did not happen and Gamani died suddenly, a very disappointed man. All this showed that the time was fraught with confusion and society was in turmoil which was to break out in a long period of terror.

Indo-Lanka Accord

I was one of the few participants who was present at President’s House when the Indo-Lanka accord was signed in the afternoon of July 29. I accompanied Gamini Dissanayake for the signing of the accord by Rajiv Gandhi and JRJ. Rajiv was accompanied by Foreign Minister Narasimha Rao and advisor Natwar Singh. On our side, Foreign Minister Hameed, Hurulle, Minister of Buddhist Affairs, Minister Devanayagam representing the Tamils and the Eastern Province and Gamini Dissanayake were present. The Prime Minister Premadasa, Athulathmudali and, surprisingly, Ronnie de Mel boycotted the meeting.

It was clear that both Rajiv and JRJ looked on Gamini as the coming man in Sri Lanka. In JRJ’s eyes his search for a loyal follower for future UNP leadership was focused now without a doubt on Gamini. When all the signing was done Rajiv went up to a mike set up in the spacious garden and said a few words of conciliation. All eyes were on JRJ when he ambled up to the mike cool as he could be under the circumstances, and gave a mini lecture on Indo-Sri Lanka relations. He ended up by looking Rajiv straight in the eye and, distilling in words the agony that India had imposed on him by their derailing of his efforts to remake Sri Lanka, said to India; “We can forgive but we cannot forget”. He then led Rajiv on foot to his office in President’s square for a no holds barred Press Conference presided over by the two leaders.

This Press Conference was a historic one. The whole of Colombo was shut down and there was an eerie silence in the administrative square which housed the President’s office. The area was guarded by a strong police contingent. Only a few hours before, the armed services had evicted a large contingent of protesters led by Bhikkhus and the SLFP, who had staged a sit in near the Fort Railway station. Mrs. Bandaranaike herself had been present and had been bundled out by the Police adding to the violence that was unleashed by UNP goons against the protesters who were non-violent.

We could hear the police sirens from the battle grounds in the Pettah. Later we heard that about a dozen protesters were killed. There were reports that gangs of protesters were approaching Colombo city from the suburbs. JR appeared to be unfazed before the media but I knew that he was worried by the rising violence which was passing from SLFP control to the violent hotheads of the JVP. JRJ dominated the press conference with his short introduction and the taking of questions from the global media.

When asked by the press as to the delay in reaching an agreement he blamed himself He said, “It was a lack of courage on my part, a lack of intelligence on my part, a lack of foresight on my part”. It was a bravura performance rarely seen in modern politics. Rajiv looked on stunned by JRJ’s candour. The press then asked him ‘who else’ hoping to cast the net wide. JRJ replied with a smile ‘the media’ drawing a laugh from Rajiv and the hard-bitten journalists who had come to cover the historic event.

Looking back this conference was the biggest event dominated by JRJ during the last days of his regime. He spoke bravely when the country was in flames and his own fate was in the balance. From now on he was put on the defensive by the JVP, supported by the SUP, which unleashed a violence in the South which could not be contained by him and was to spill over to the Premadasa era till the JVP leaders were physically eliminated in 1989. Sri Lanka entered an era of uncertainty and social disruption which blighted the legacy of President Jayewardene which held spectacular promise in its first years. The monolithic UNP which held sway earlier was fragmented and it took all the leader’s skills to even keep it together and pass the baton on to Premadasa. But on that day the future was uncertain and posters threatening to ‘Kill the old man’ began to appear all over the country. An attempt was made on Rajiv’s life by a JVP indoctrinated naval rating and two Indian destroyers steamed into Colombo harbour to show that India will not stand idly by. It was a time of a national tragedy and all eyes were on the implementation of the Accord. The violence unleashed by the JVP compelled JRJ to ask Rajiv for the induction of the Indian Peace Keeping Force [IPKF] which was the first time after independence that a foreign military force was stationed in strength in the country with their own command structure and tasks which were identified by their own leaders.

The President could not deal with the military situation in his own country as he could not do battle in both the North and South of the country at the same time. It must be mentioned here that our military top brass concurred with this decision though they were unhappy to be ‘confined to barracks in the North’. This was particularly so because the Jawans’ who were flown in from South Indian bases were of poor quality.

On a visit to Katunayake I saw them emplane for the North from there. Sonic were dragging well fed goats with them, obviously for a tasty ‘mutton curry’ in their camp. Others were crowding the duty free shop buying everything available on their payday. Though they were under orders to confine themselves to the Northern and Eastern theatre, their intelligence had not indicated that Trincomalee district was multi-ethnic. Due to the activity of the IPKF and the LTTE and the enforced inactivity of the Sri Lankan army, the Sinhalese and Muslims of the East started to stream south for safety, adding more pressure on JRJ who could not depend on Premadasa or Lalith to support him. Only Gamini Dissanayake stood by him and I shuttled between ‘Braemar’ at id Dixit’s residence to seek information on the plans of the IPKF, since the chain of command was broken. To make matters worse, Dixit himself was not kept informed by the Indian Military in Trincomalee and he was getting alarmed and even threatening quit if he was being undercut by Delhi.

LTTE and JVP Reaction

According to the Indo-Lanka agreement the LTTE was to hand over their weapons to the Sri Lankan armed forces under Indian supervision. What actually happened was a farce which was enacted by the LTTE in violation of the agreement. The LTTE hid its heavy weapons and only offered a token pistol to the army. The other Tamil parties were ready to comply but had the legitimate fear that once they disarmed, they would be massacred by the LTTE. Government made plans for reconstruction of the North and East. The Indian High Commission under Dixit went on overdrive to please Rajiv but the media and the opposition in the South began a virulent campaign against the Indians. For the first time the hitherto monolithic UNP began to crack, largely because the PM and his coterie of MPs showed their displeasure in no uncertain terms.

Premadasa made his famous Angoda Temple speech criticizing the Accord and by implication the President. SLBC brought the tapes of the speech to me and asked for instructions regarding broadcasting it that night with the news. At this point news of my dilemma had reached Premadasa through his henchmen in SLBC.I got a call from Wijayadasa the PM’s Secretary, telling me that his boss was very disturbed by the delay and that I should not be guided by Gamini Dissanayake’s advice on this matter. It was a hot potato and I took the tapes and the DG of SLBC Anura Goonesekere to ‘Braemar’ for the President’s instructions. JRJ was worried and did not have his usual ‘sang froid’. He asked me what we should do and I suggested that we should use an edited version leaving out the venomous attacks. He agreed and we broadcast a watered down version that night.

That seemed to have satisfied the PM who had been informed by his henchmen that we would censor his speech ‘in toto’. Perhaps he was spoiling for a fight on this issue. JRJ on the other hand was very keen to retain the PM’s support at this crucial juncture. He was aware that the SLFP had dangled a carrot before Premadasa saying that the SLFP would back him and Mrs. B would not enter the fray if he sabotaged the Accord. It was a time of moves and countermoves and the Government which was designed to last forever and a day was on the edge of crumbling. Two Southern MPs who had ridden on JRJ’s coattails did not vote for the 13th amendment designed to give effect to the Accord. Another MP from the south who was considered to be a tough guy from Tangalle was murdered by the JVP on his way back from Colombo to his electorate.

The JVP under Rohana Wijeweera who was in hiding with his top leaders as his party was proscribed, launched a murderous attack on all those who supported the Accord, including the leaders of the left-particularly the LSSP, CP and the NLSSP who though advocates of revolution were ill prepared for political violence on this massive scale. While the LTTE had murdered left leaders of the North, the JVP followed suit by murdering leftists in the South. The CP which was active in the grassroots in the South and was a rival to the JVP was decimated.

An early indication of the ruthlessness of the JVP was the horrific murder of the popular student leader of the Colombo campus named Daya Pathirana who opposed their taking control of the student movement which was a power base for their politics. Another innovation of the JVP was the mass induction of young monks, particularly from the universities, as a cover for their political work and military operations. As De Silva and Wriggins have written, many of these monks made bloodcurdling threats which even embarrassed JVP members. As the encounters became even more violent some of these monks gave up robes and emerged as front line leaders of the party. Others, as I have described earlier, jumped ship by migrating to Europe where their supporters had infiltrated the new temples built by JVP oriented migrants in the hig cities.

Interlude

While the JVP and its allies stepped up their protests, the North saw a period of peace which was acclaimed by the international community. A relief and rehabilitation package was negotiated with international donors and inter district movement, particularly visits of Buddhists to Nagadipa, was encouraged. University administrators held their annual conference in Jaffna and we were able to arrange special railway trips from Colombo to Jaffna. Local and foreign journalists were encouraged to report from the North and business slowly resumed, particularly in respect of agricultural produce which was in high demand in the South. The situation was slowly returning to normal when several unfortunate events, some by design, upset the fragile peace. The first was the internecine conflict between the Tamil militants.

Many non LTTE groups became close to the IPKF and on occasion became their informers and proxies. At this stage the LTTE launched murderous attacks on the other Tamil parties partly because they had not given up their claim to be the ‘sole representative’ of the Tamil people and partly because the truce with the Sinhala forces enabled them to turn their attention to the rivals closer home who were being disarmed by the IPKF. The upshot was that ‘the short stay’ of the IPKF promised by Rajiv became a farce and they got bogged down in a disastrous war which finally led to the assassination of Rajiv himself. The LTTE was refusing to play by the Indian playbook and the country was slipping further and further into a cycle of violence over which nobody had control. This was a nightmare period for JRJ, who assailed in the North and South, had to confront dissatisfaction within his party ranks, led by the PM no less. Soon it became life threatening to the party leaders when an assassination attempt was launched by a JVP cadre who was a senior member in the party, inside Parliament itself The mistrust in the party had grown to such an extent that the PM was initially suspected of being one of the conspirators.

Assassination Attempt

While the UNP parliamentary group was meeting as customary in a committee room in parliament an employee opened a door to the room and lobbed a hand grenade into it. Without doubt the target was JRJ whom the JVP had built up as a hate figure. Luckily for the 81 year old President the grenade hit his desk and rolled away from him and exploded further away killing the MP for Morawaka, Abeywickreme. Lalith Athulathmudali was seriously injured and had to be rushed for emergency surgery. the Prime Minister was also injured but not seriously. According to the President he had been saved because the PM had pushed him under the table so that the shrapnel did not hit him. Within a short time after the attack I got a telephone call to say that the President wanted me to come immediately to the Army OPS Combine office in Flower road.

When I went there JRJ had just arrived with blood splattered all over his tunic. He was in shock and asked us what we should do? I had read much about the Kennedy assassination and told him that we had to immediately do two things. One was to ensure that there was no further attacks due from a wide ranging conspiracy and secondly to inform the country that he was safe and that the conspiracy had failed. He agreed and I sent for a Rupavahini camera crew and alerted the channels about an imminent announcement by the President.

JRJ wanted a few minutes to compose himself and faced the cameras in a live broadcast with the blood on his tunic seen clearly. He identified the attack as an assault on democracy and went out of his way to assure the public that the PM, though slightly injured, was safe. That took the sting out of the speculation that the PM had engineered this attack. It was a miracle that the President had survived but it added to his woes as a leader and encouraged some ministers, especially Ronnie de Mel and Nissanka Wijeratne to think of jumping ship. JRJ by shrewdly bringing in the PM as a victim ensured that the party would not be weakened further. The Thirteenth Amendment

Action now shifted to the 13th amendment which was to give legal effect to the provisions of the Indo-Lanka agreement. Challenges to it were launched by different opposing parties including the alliance of major opponents called the Mavbima Surakeeme Viyaparaya [MSV] which was led by Maduluwawe Sobhita. It was a powerful organization and with the JVP raising the ante with violence, the judgement of the full bench of the Supreme Court on the Constitutional amendment bill became absolutely crucial.

JRJ was confident of his two third majority in Parliament. But if it came to a need for approval in a referendum, the bill was as good as dead. Everybody was on tenterhooks while awaiting the verdict. Premadasa also realized at this juncture that he had gone too far. This was a period when, for the first time, JRJ and Premadasa were really estranged. With all the hostility to Premadasa in the party JRJ had stood by him and had given him his due. He remembered the time when he and Dudley had paid a salary to the up-and-coming Premadasa with their personal funds. Even at this stage he was loath to discipline the PM but he sent a clear message that he was annoyed by removing Sirisena Cooray from the Executive Committee of the party, together with Ronnie de Mel who had resigned from the Cabinet by then.

Premadasa then pulled back stating that he was willing to abide by the decision of the Supreme Court regarding the 13th amendment. This was because he had been assured by Raja Wanasundera who was a senior judge sitting on this very bench, that a referendum will become necessary. Raja was a close friend of M Fernando who acted as Premadasa’s emissary on this issue. But this tactic backfired because Justice Parinda Ranasinghe provided a majority to the verdict of the Bench of judges which held that a referendum was not necessary and that the amendment could be passed with a two third majority in Parliament. JR cracked the whip, and the Bill was passed in the midst of unprecedented security, when the MPs had to be bussed with an armed escort to Parliament and back to the heavily guarded hotel in Colombo which was booked for them. The PM true to his word moved the Bill in Parliament. But Colombo was like a war zone and the Government appeared to be tottering. This was a nightmare for JRJ, with his party officials being killed en masse and even some of his MPS like De Silva of Habaraduwa and Tikiri Banda of Galagedera being killed in a brutal fashion.

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

Features

Special milestone for JJ Twins

The JJ Twins, the Sri Lankan musical duo, performing in the Maldives, and known for blending R&B, Hip Hop, and Sri Lankan rhythms, thereby creating a unique sound, have come out with a brand-new single ‘Me Mawathe.’

In fact, it’s a very special milestone for the twin brothers, Julian and Jason Prins, as ‘Me Mawathe’ is their first ever Sinhala song!

‘Me Mawathe’ showcases a fresh new sound, while staying true to the signature harmony and emotion that their fans love.

This heartfelt track captures the beauty of love, journey, and connection, brought to life through powerful vocals and captivating melodies.

It marks an exciting new chapter for the JJ Twins as they expand their musical journey and connect with audiences in a whole new way.

Their recent album, ‘CONCLUDED,’ explores themes of love, heartbreak, and healing, and include hits like ‘Can’t Get You Off My Mind’ and ‘You Left Me Here to Die’ which showcase their emotional intensity.

Readers could stay connected and follow JJ Twins on social media for exclusive updates, behind-the-scenes moments, and upcoming releases:

Instagram: http://instagram.com/jjtwinsofficial

TikTok: http://tiktok.com/@jjtwinsmusic

Facebook: http://facebook.com/jjtwinssingers

YouTube: http://youtube.com/jjtwins

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Features7 days ago

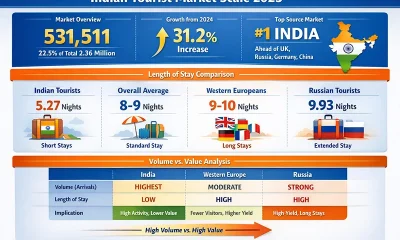

Features7 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoFuture must be won

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository