Opinion

Drought, El Nino, agriculture and food security: What Sri Lanka can do

By Prof. W.A.J.M. De Costa

Senior Professor and Chair of Crop Science,

Faculty of Agriculture, University of Peradeniya

At present, Sri Lanka is going through a prolonged rain-free period. Several parts of the country are experiencing an unprecedent drought with the Udawalawe reservoir running almost dry for the first time in fifty years. It is reported that water levels of most tanks and reservoirs are below 50% of their capacity. Agriculture, being an activity of extreme sensitivity to the variations in climate, has taken a severe hit. We see images of dried and scorched crops and the inevitable pleadings and protests from the farmers demanding water from reservoirs be released to their fields along with demands for compensation for crop losses. While the climatic variations are beyond our control, the question arises as to whether we could have anticipated the drought and put measures in place to better manage its potential impacts on Agriculture. An analysis of these issues, while coming too late to alleviate the present crisis, will be useful for the future as scientific evidence indicates that this scenario is likely to be repeated with greater frequency in the foreseeable future.

What has caused drought, and could it have been predicted?

The general rainfall pattern in Sri Lanka dictates that a drought could be expected during the period from July to September in the dry- and intermediate climate zones, which broadly include all parts of the country except its southwest and the western slope of the Central Highlands. The South-West Monsoon which brings rainfall during the period from May to September to the wet zone in the southwest of Sri Lanka does not go beyond the western slope of the Central Highlands, which act as a physical barrier for extending the rains to the rest of Sri Lanka.

Therefore, crop fields in the dry- and intermediate zones receive very limited rainfall at the beginning of the yala season in the second half of April and the first half of May. Thereafter, there is no assured and consistent rainfall generating process for these climatic zones until the Second Inter-Monsoon which sets in from October onwards, largely as a result of tropical atmospheric depressions in the region around the Bay of Bengal. Therefore, the present drought cannot be considered as entirely unexpected.

What has happened in Sri Lanka is that the rainfree period that generally occurs during the July-September period in the dry- and intermediate zones has intensified into a severe drought. Even though the full rainfall data are not yet available, it is highly likely that rainfall from the South-West Monsoon has been below-average in 2023. This has meant that even the limited amount of rainfall that normally occurs at the beginning of the yala season was decreased, thus increasing the possibility of water shortage for crops at an earlier point in the current season than in a season of normal rainfall.

Lower rainfall from the South-West Monsoon in the wet zone means less water in the major reservoirs and tanks in the dry zone that are fed by the rivers originating from the Central Highlands (e.g. Mahaweli, Walawe) and the reservoirs located in the wet zone (e.g. Kotmale, Victoria).

Intensification of the ‘normally expected’ drought during this time of the year has been caused predominantly by the atmospheric phenomenon known as the ‘El Niño’, which had been predicted to occur in the middle of 2023, based on the climatic patterns observed in 2021-22 and the early months of 2023. El Niño is a process triggered by a weakening of the atmospheric air circulation (i.e. wind) patterns above the Pacific Ocean around the equator. Such a weakening of atmospheric circulation patterns disrupts the normal pattern of ocean evaporation, cloud formation and rainfall.

This disruption of wind patterns brings droughts to Australia, tropical East Asia (e.g. Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka etc.) and some parts of South America (e.g. Brazil) while bringing heavy rainfall and floods in some parts of South America (e.g. Peru). El Niño events usually happen at a frequency of 1-3 times every decade.

The opposite cycle of El Niño, called La Niña, also happens at an approximately similar frequency where the wind patterns are unusually strengthened bringing excess rainfall to tropical Australasia and causing droughts in tropical South America. During an El Niño event, global air temperature increases above average whereas the opposite happens during a La Niña event. During an El Niño year, sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific near South America (e.g. Peru) increase above average, and thereby provides an early warning signal. Such an increase had been observed during the first few months of 2023 and by April, climate scientists had predicted an El Niño during the middle of 2023.

Furthermore, they had warned that the El Niño in 2023 could be unusually strong (called a ‘Super El Niño’) because the last three years (2019-22) had seen a rare continuous run of La Niña, thus raising the possibility of it being followed by an El Niño. This information and early warnings should have been available to Sri Lanka’s Department of Meteorology who should have alerted the relevant authorities and stakeholders such as the officials of the Ministries of Agriculture, Power and Energy and the farmers.

What measures could be taken to protect Agriculture from the impacts of drought?

Early warning, preparation and making adjustments in advance are key to minimising the impacts of a drought on Agriculture as options are very limited once a drought sets in.

Early warning: Why was it not there?

Early warnings on impeding droughts can be issued based on analyses of the current and past meteorological data from land, atmosphere, and ocean. Large volumes of data from several sources are fed to models that describe the behaviour of climate and weather based on the laws of physics. These models, which are run on high-performance supercomputers, make predictions of the future weather patterns. Different global agencies such as the US National Oceanic and Atmosphere Administration (NOAA) and the UK Met Office run these models on a global scale, and their predictions are made available to the relevant agencies of countries which do not have the capacity to develop and operate their own models (e.g. Sri Lankan Department of Meteorology).

Prediction of weather is a complex and tricky exercise, where there is a possibility of getting the predictions wrong. The highly chaotic nature of the atmosphere and incomplete understanding of the processes means that none of the predictions are definitive. Only the probability of a certain weather event occurring within a given period can be given and often different models provide different probabilities for the same event. An unforeseen or previously unaccounted atmospheric disturbance can cause a sudden and large-scale impact on the entire weather system so that predictions given only a few days ago may not come true.

A small country such as Sri Lanka has the added complexity that it is represented by only a small portion of the global grid. The climate models are run separately and concurrently for small segments of the earth (called ‘grid cells’) and overall predictions are made by combining the model predictions for each individual cell. Sri Lanka falls within a small number of grid cells so that the predictions from these global scale climatic models are not specific enough to be of use in making decisions about important weather-dependent activities such as Agriculture. This is especially true when we take in to account the fact that Sri Lanka is divided in to 46 different agroecological regions based on the diverse combinations of climate and soil conditions that are found within such a small country.

Overcoming the above methodological difficulties in the prediction of weather (short-term variations) and climate (longer-term variations), especially given the limited resources available to the Sri Lankan Department of Meteorology, is challenging, but not impossible. Greater vigilance and monitoring of the forecasts, especially the medium- to long-range forecasts, from global weather and climate models put out by the global agencies could help the Sri Lankan meteorologists to look for similar patterns in the local weather data as they come in. Weather and climate forecasting involves the expertise, local knowledge and judgement of the meteorologists to translate model outputs into practically usable forecasts.

Conversion of larger scale model outputs to smaller scale local areas (called ‘down-scaling’) requires research which develops relationships between atmospheric processes and climatic factors at different scales. For Sri Lanka, a network of weather stations with sufficient geographical coverage to take into account the 46 different agroecological regions is essential to generate the data that will enable the local meteorologists to develop meaningful down-scaling procedures and make sufficiently accurate predictions.

The current number of weather stations which measure all required climatic factors in Sri Lanka is woefully inadequate and little initiative has been taken in recent times to develop and expand capacity in this vital area despite the obvious threat of climate change. Agencies such as the UK Met Office and NOAA are research hubs staffed with a large number of climate scientists and have close links to the university system of those countries and beyond.

In contrast, very little research takes place in the Sri Lankan Department of Meteorology and there are no formal links to the university system. Urgent initiatives are required to address these shortcomings in Sri Lanka’s capacity to forecast weather and climate especially given the clear and present danger posed by climate extremes such as droughts which are predicted to increase in their frequency as a result of climate change.

Preparation and making adjustments: Were they done?

Agriculture, especially the cultivation of crops, is an activity which is extremely sensitive to climatic conditions that the crops would experience in a given season. In Sri Lanka, the climate sensitivity of its crop production is further increased by the fact that rice, which provides its staple food and on which its national food security depends, is a crop which has an unusually high-water requirement in comparison to other major staple food crops such as wheat and maize. As such, adjustment of the cropping practices in accordance with the expected rainfall and water supply is essential for the cultivated crops to survive an expected drought until they are harvested.

A general principle that is adopted in drought-prone regions all over the world is to grow short-duration crops which are able to complete their cropping cycle before the drought intensifies (known as ‘drought escape’). This is especially relevant in the yala season in the dry- and intermediate zones of Sri Lanka because the drought that develops from mid-July onwards persists until October (and therefore called ‘terminal drought’). For such seasons, the Rice Research and Development Institute (RRDI) of the Sri Lankan Department of Agriculture has developed rice varieties which provide a harvest in 2 ½ – 3 months (e.g. Bg251, Bg314). However, it is clear that the majority of farmers have not opted for these varieties, but have instead cultivated their preferred varieties, which are of longer duration and therefore got caught in the drought before they mature.

Irrespective of the duration of the variety, timely commencement of cultivation with the onset of the limited rainfall in late-April and May is crucial for the crops to escape the drought that develops later in the season. Unfortunately, Sri Lankan farmers do not have a good track record in this regard. If rice crops had been established by the end of April with land preparation either before or after the Sinhala and Hindu New Year, even a three-month rice variety would have been harvested by the end of July.

In such crops, the need for water would have decreased from mid-July onwards because the water requirement of rice decreases during its final grain filling period. Therefore, while there are no records to verify this, there is a high likelihood that rice crops that have got caught in the drought are late-planted crops and most likely of longer duration (i.e. 3 ½ to 4 months) varieties.

There are reports that during the time when water was initially released from the Uda Walawa reservoir, a majority of the farmers had not begun their cultivation. Uncertainty about the supply of fertilizer may have played a part in farmers delaying commencement of cultivation, but it has proven to be a costly delay.

Selection of which crops to cultivate is a crucial decision prior to a season where a drought could be expected. In this regard, the recommendation from the Department of Agriculture is to cultivate short-duration rice only in fields where there is a reasonably-assured supply of water and to grow other field crops such as short-duration legumes (e.g. mung bean, cow pea, soya bean etc.) in fields where there is a likelihood of a water shortage. However, there is an inherent reluctance on the part of the farmers to follow this recommendation.

The preference is to cultivate rice irrespective of whether sufficient water would be available or not while ignoring any warnings from the Departments of Meteorology and Agriculture. There is a fair percentage of Sri Lanka farmers who practice rotation of crops, which has many agronomic advantages such as restoring soil fertility and breaking the pest- and disease cycles. However, changes in the choice of crops, especially at short notice, in response to an early warning of possible extreme climatic events such as drought, is not a practice that is ingrained in the psyche of the average Sri Lankan farmer.

Using the limited amount of available water efficiently, with minimum wastage, is essential to avoid crop failure during a drought-affected season. The predominant method of irrigation employed by Sri Lankan farmers involves saturating the soil by applying water along the surface. In rice cultivation, this is taken even further by maintaining a layer of standing water. These methods of water management require large quantities of water along with substantial wastage due to evaporation, lateral seepage and deep drainage (i.e. water draining down below the crop’s root zone).

Research has shown that in many crops, including rice, the soil need not be saturated throughout the crop’s duration for it to have sufficient water for its growth. In rice, there are alternative water management methods such as ‘alternative wetting and drying’ and ‘saturated soil culture’, which do not require standing water to be maintained at all times, and therefore require less water. These alternative methods require more precise management of their crops by the farmers. Unfortunately, they have not gained much acceptance by the farmers despite the efforts of researchers at the RRDI.

Role of governmental agencies: Did they do their job?

The governmental agencies, run by the taxpayer’s money and the indirect tax paid by the general public, have an important contribution to make to enable Sri Lankan Agriculture to withstand climate-related shocks such as the current drought, the frequency of which is predicted to amplify with climate change. While the Department of Meteorology needs to step up in providing forecasts with greater precision and credibility, the Department of Agriculture (DoA) of the central government and the Provincial Departments of Agriculture need a major shake-up of their programs and activities to build resilience in the food production system and among the farmer community to better manage similar drought episodes in the future.

While the research arm of the DoA should continue its efforts to develop crop varieties with greater genetic tolerance to drought, the extension arms of the DoA and the Provincial DoAs have a huge role to play in changing famer perceptions and convincing them to adopt cultivation strategies and practices that will increase the resilience of their farming systems against drought.

All these governmental agencies are hugely under-staffed and under-resourced with very low levels of motivation for innovation while being steeped in routine practices. As a result, these agencies and their officials have lost credibility in the eyes of the farmers so that their recommendations are not taken seriously and adopted. Therefore, there is a need to restore credibility and confidence among the farming community by more focused proactive activities with a clear vision and better planning.

The current crisis clearly demonstrated that there is no proper coordination between the relevant governmental agencies when addressing the multiple challenges faced during a drought. It is important that mechanisms are put in place for a coordinated response during a drought where all parties work with better understanding and flexibility while keeping the greater goals of protecting national food security, farmer livelihoods and energy security in focus.

Role of farmers: Are they willing to adapt and change?

Farmers are key stakeholders in Sri Lanka’s efforts to ensure national food security and as such are highly influential in shaping the interventions and policy initiatives to meet the challenges posed by drought and other climate-related events that affect Agriculture. While the government has the responsibility of ensuring the availability of key resources for farming such as fertilizer, water, seeds, fuel etc., the farmers, in turn, should have the willingness to adapt and change their age-old cultivation practices and perceptions to follow recommendations that are issued after careful research and field validation. A paradigm shift is needed on the part of the farmers as well.

Opinion

Open letter to PUCSL on proposed electricity tariff revision

Although the Public Utilities Commission of Sri Lanka (PUCSL) has appropriately invited public consultation on the proposed electricity tariff revision from 27 February to 18 March, the online submission portal appears to contain a non-functioning submission tab. If this technical issue persists, it risks undermining the integrity and effectiveness of the entire consultation process. Consequently, I have chosen to present this letter openly for public consideration, including by the PUCSL.

Current geopolitical tensions in the Middle East underscore the urgent need for Sri Lanka to minimise its dependence on imported fossil fuels and prioritise the development of domestic renewable energy resources, including solar, hydro, and wind power. Such a transition is essential to securing a stable and independent energy supply. Regrettably, the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) appears to be moving in the opposite direction.

Promoting solar-powered electric vehicles supported by home-based renewable charging systems would strengthen national energy security and reduce pressure on imported fuel supplies. The fuel queues witnessed during periods of crisis, most notably in 2022, serve as a stark reminder of the risks associated with excessive dependence on external energy sources and the national anarchy that can follow.

As a small nation operating within a volatile global economy, Sri Lanka must remain as non-aligned and self-reliant as possible. Strengthening self-sufficiency in strategic sectors is critical to avoiding collateral damage amid escalating geopolitical rivalries among major powers. India has made steady progress along this path; Sri Lanka would be well-advised to do the same.

Raising electricity tariffs — a measure repeatedly adopted over the past decades to offset the high cost of fossil-fuel-based power generation — places an unfair burden on debt-ridden households and struggling businesses. Resorting once again to tariff increases, rather than addressing structural inefficiencies and fuel dependency, reflects a failure of long-term planning. The nation must instead pursue sustainable energy solutions that reduce costs over time.

As a debt-burdened country, Sri Lanka urgently requires pragmatic, forward-looking strategies that ease the pressure on citizens while strengthening resilience in times of geopolitical instability. Energy pricing is not a peripheral issue; it is a central pillar of economic stability and national security, demanding serious and immediate attention.

Established on 1 November 1969, the CEB was entrusted with the responsibility of generating and distributing electricity across the island while promoting social and economic development through the optimal use of national resources.

Recent developments suggest that the Ceylon Electricity Board has fallen short of these foundational objectives. Over the past two decades, electricity tariffs have been increased repeatedly under various justifications yet supply reliability has not consistently improved. The current proposed revision appears to perpetuate the same pattern: continued dependence on imported fossil fuels, directly contradicting the principle of optimally utilising national resources. This trajectory risks returning the country to recurring crises, including the prolonged fuel shortages and power cuts experienced in recent years.

Energy is not an ordinary commodity confined to a single sector; it affects every dimension of national life. High energy costs increase the cost of living by inflating expenses related to food production, transportation, manufacturing, and consumer goods. Ultimately, these costs are borne by citizens.

Moreover, elevated energy prices undermine national competitiveness by discouraging foreign investment and constraining local entrepreneurship, technological advancement, industrial expansion, and job creation. High-cost energy impedes national development.

Low-cost energy should therefore be formally adopted as a national policy objective. The CEB must adhere to its original mandate of optimising national resources for cost-effective electricity generation. Any deviation from this principle must be fully transparent and supported by clear, evidence-based justification.

Even in the sphere of renewable energy, concerns arise about the apparent preference for large-scale solar and battery storage projects that require substantial public funding. Previous claims of “grid instability” attributed to household rooftop solar generation were used to justify policy shifts. If electricity generated by rooftop solar during daylight hours was considered problematic, how would significantly larger solar installations differ in principle? Without systematic and transparent grid modernisation, such projects risk becoming costly stopgap measures rather than sustainable long-term solutions.

Poorly planned initiatives could once again expose the country to high delivery costs, reflected in elevated tariffs. They may also increase the risk of power disruptions due to battery limitations, spare-part shortages, infrastructure weaknesses, or maintenance failures. Sri Lanka has previously endured six- to ten-hour power outages, with severe economic and social consequences. The nation cannot afford a return to such instability.

It must also be recognised that rooftop solar installations, financed by homeowners — often through personal loans — have provided a crucial safety net for many families. By purchasing surplus energy from these “prosumers,” the system has functioned in a mutually beneficial manner for both households and the nation. Rather than discouraging decentralised generation, Sri Lanka should modernise its grid and meaningfully integrate citizen-led energy production. Short- and medium-term grid improvements could be facilitated through structured private-sector participation, including by prosumers themselves.

Globally, affordable energy underpins economic growth. Countries such as China, the United States, Norway, Brazil, and Canada have leveraged domestic energy resources to produce cost-effective power and accelerate development.

Sri Lanka must adopt a clear national policy centred on low-cost energy, fully utilising its natural endowments — solar, hydro, wind, and emerging technologies. Proposals prioritising imported fuels should be considered secondary and strictly transitional.

A nation that endures long queues for essential energy supplies cannot reasonably expect its citizens and businesses to remain productive and resilient. These realities are fundamentally incompatible.

Encouraging decentralised energy production would:

* Reduce the cost of living

* Improve national resilience

* Attract foreign investment

* Create employment

* Enhance export competitiveness

The people have entrusted the government with this responsibility. The time has come for a decisive, transparent, and forward-looking policy shift.

Chula Goonasekera

(cgoonase@sltnet.lk)

A concerned citizen

Opinion

Need for well-designed contracts and their implementation

The purchase of substandard coal using a faulty tendering process has become news lately. This enormous financial loss to the country indicates the urgent need for the Government to pass stronger contract laws and have their proper implementation in Sri Lanka by professionals. It is recommended that “Model” contracts need to be drawn up as typical examples and these made available to governmental departments who may need to enter into similar contracts. Do not ask a busy manager to design a contract, a legal document from scratch! Perhaps a whole department should be set up to monitor (police?) government and local government administration of contracts under English Contract Law and contracts under the United Nations Convention for International Sale of Goods (CISG). Perhaps now, it seems that anyone in government can draw up a contract and design it to suit his own whims and fancies!

I suggest here models of typical contracts, useable for different cases are made available for anyone or any department required to enter into a contract to enable them, or at least assist them to first formulate, and draw up an effective contract which must have certain important clauses. Contract administrators and supervisors need to be well trained, motivated and independent in order to administer Government contracts as the law of Sri Lanka should demand.

Contract Management

In the West, mutually agreed contracts are considered legal agreements enforceable by law under a given jurisdiction. There is the initiator of the contract named the Owner and a Main Contractor who agrees to implement the work for a price consideration, and who may delegate part, or all of the work to sub-contractors.

Contracts must provide all the information required by a contractor to complete the work. Contract clauses must incorporate all foreseeable eventualities. For example, the acceptance, as agreed and signed between the contacting parties by the supplier or lead contractor, needs to have clauses that allow for design changes (change orders), additional time and the formulation of related costs and profit accordingly. Such ‘in progress’ changes have procedures which are given in clauses dealing with ‘change orders’ which require assessing the cost of the change order implementation. Change order management may best be done by a firm of Quantity Surveyors.

The main contractor agrees with the owner to supply labour, materials and specialist equipment to fulfil the terms of the agreement or contract for a price. Special tax concessions, customs clearances and other legal requirements can fall on the shoulders of the Owner, or as negotiated from the outset. All these matters need to be clarified from the outset of any contract.

Time is of the essence. The time value of money is always at the forefront of the contract manager’s mind. The work is usually expected to be carried out to a time frame set by the owner. Therefore, the implementation of an agreement should be set in an agreed time frame with easily defined milestones marking progress and marking when appropriate payments become due.

Of course, contract administrators must make payments only when the work is verified as satisfactorily completed at each of previously agreed stages of the contract. Usually, there are time limitations, with penalties for time overruns. Owners want their goods delivered on time and to meet all contractual specifications on quality and performance. There should be clauses stipulating quality and quantity guarantees and guarantees of remedial repairs, continuing service agreements to be settled before an official handover and signing on completion of a contract. Final payment should be withheld until the guarantee period has expired. Preparing for these events needs computers, foresight and experience.

Small contracts are usually managed by the owner, but large, multimillion dollar contracts may be administered by an independent organisation. A contract is enforceable by law, with stated financial penalties for failures to abide by the terms of the contract, but all is subject to “Force Majeure.” This is when progress of the work is seriously impeded or impossible due to events totally outside the control of the Subcontractor.

Contract implementation is a large area, well catered for by laws in the English language. This letter can only raise questions about the quality of contract administration in Sri Lanka. Unfortunately, so few legislators have sufficient knowledge of English, resulting in loopholes allowing manipulation which may result in Sri Lankan public having to pay through the nose, pay dearly for incompetent practice.

I can suggest these improvements, but my actual experience is that all my letters, in English, to officialdom go unanswered and ignored.

Roger. O. Smith

Opinion

Sri Lanka Cricket needs a bitter pill

A systemic diagnosis of a fading legacy

The outcome of the 2026 T20 World Cup, coupled with the trajectory of the sport in recent years, provides harrowing evidence that Sri Lankan cricket is suffering from a terminal malignancy.The Doomsday clock for Sri Lankan cricket has not just started ticking—it has reached its final hour.

Therefore this note is written to call the attention of the cricketing elite who love the sport.

The current state of affairs suggests a pathology so deep-seated that conventional remedies—be it revolving-door coaching changes or fleeting, opportunistic victories—can no longer arrest its spread.

What we are witnessing is not a mere slump in form or a temporary lapse in rhythm; it is a profound systemic collapse that threatens the very foundation of our national pastime.

The Illusion of Recovery: The “Sanath Factor” as Palliative Care:

Since late 2024, the appointment of Sanath Jayasuriya as Head Coach injected a much-needed surge of adrenaline into the national side.

Statistically, the highlights were historic: a first ODI series win against India in 27 years, a Test victory at The Oval after a decade, and a clinical 2-0 whitewash of New Zealand.

However, a data-driven autopsy reveals that these will be “palliative” successes rather than a cure.

Under Jayasuriya’s tenure, the team maintained a win rate of approximately 50 percent (29 wins in 60 matches).

While analysts optimistically labeled this a “transitional phase,” the recent T20 series against England and Pakistan exposed the raw truth: in high-pressure “crunch” moments, the team’s performance metrics—specifically Strike Rate (SR) and Fielding Efficiency—regress to amateur levels.

We are not transitioning; we are stagnating in a professional abyss.

The Scientific Gap:

Why India and Australia Lead

The disparity between Sri Lanka and global giants such as the BCCI and Cricket Australia (CA) is now rooted in High-Performance Science and Algorithmic Management.

Predictive Analytics & Biometrics

In Australia, fast bowlers utilise wearable sensors to monitor workload and biomechanical stress.

AI models analyse this data to predict stress fractures before they occur.

Sri Lanka, conversely, continues to cycle through injured pacemen with no predictive oversight.

Virtual Reality (VR) Training

While Australian batters use VR to simulate the trajectories of elite global bowlers, Sri Lankan players remain tethered to traditional net sessions on deteriorating domestic tracks.

Data-Driven Talent Identification:

India’s “transmission system” utilises automated data analysis across thousands of domestic matches to identify players who thrive under specific pressure indices.

In Sri Lanka, 85 percent of national talent still originates from just four districts—a statistical failure in talent scouting and geographic expansion.

Infrastructure vs. Intellect:

A Misallocation of Capital

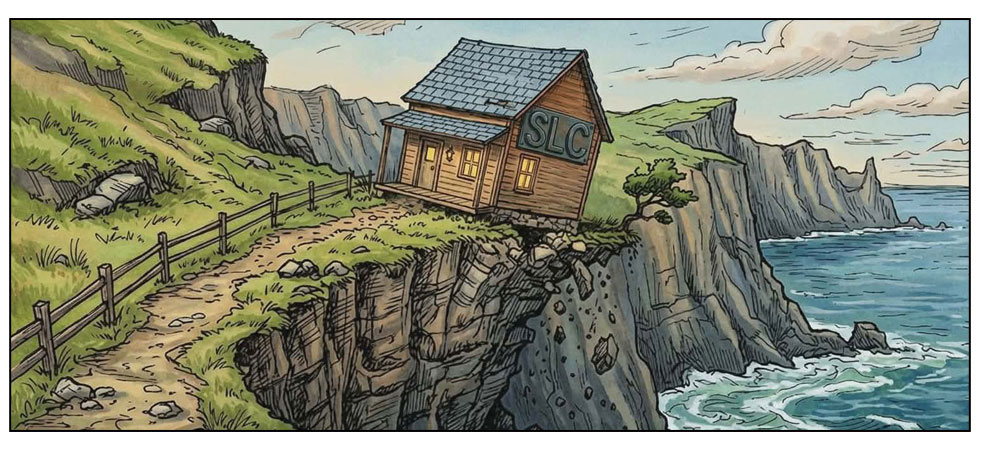

Sri Lanka Cricket (SLC) boasts massive reserves, yet its investment strategy is fundamentally flawed.

Capital is funneled into “bricks and mortar”—grand stadiums and administrative buildings—rather than the human capital of the sport.

We build colosseums but fail to train the gladiators.

The domestic structure remains a “spin trap.”

By producing “rank turners” to suit club politics, we have effectively de-skilled our batters against elite pace and rendered our spinners ineffective on the flat, true wickets required for international success.

The Leadership Deficit:

A Failure of Succession Planning

The crisis of leadership post-Sangakkara and Mahela is a byproduct of poor “Succession Science.”

Australia maintains a “Culture of Continuity,” backing leadership even through lean periods to ensure stability.

India employs a rigid “Succession Roadmap,” ensuring the next generation is integrated into the system long before the veterans depart.

In contrast, SLC operates on a “carousel of convenience,” changing captains and coaches to distract from administrative failures.

This lack of imaginative management stems from a low literacy in modern Sports Governance.

From a philosophical perspective, our established cricketing traditions have failed to absorb the antithesis of the modern, hyper-professionalized global game.

As a result, a truly modern Sri Lankan brand of cricket has failed to materialise.

Instead, we are trapped in what is called a “Static Synthesis,” where the administration clings to the glories of 1996 and 2014 as a shield against the necessity of change.

This is not a transition; it is a refusal to evolve

We are witnessing the alienation of the sport from its people, where the “Master” (the administration) has become detached from the “Slave” (the grassroots talent and the fans).

The Verdict:

A National Emergency

The “cancer” in Sri Lankan cricket is a trifecta of political interference, irrational management, and a refusal to embrace the Fourth Industrial Revolution (AI, VR, and Big Data).

As someone who contributed to the formation of the Sri Lankan Professional Cricketers’ Association, I see the current trajectory as a betrayal of the players’ potential and the nation’s heritage.

Sri Lanka Cricket does not need another “review committee” or a new coach to act as a human shield for the board.

It needs a “Bitter Pill”—an aggressive, independent restructuring that prioritises scientific professionalisation over cronyism.

Without this, our cricket will remain at the bottom of the well, looking up at a world that has moved light-years ahead.

Shiral Lakthilaka

LLB, LLM/MA

Attorney-at-Law

Former Advisor to H.E. the President of Sri Lanka

Former Member of the Western Provincial Council

Executive Committee member of the Asian Social Democratic Political Parities

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoAn efficacious strategy to boost exports of Sri Lanka in medium term

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoOverseas visits to drum up foreign assistance for Sri Lanka