Features

Travelling for WHO – first to Botswana in Africa

Excerpted from Memories that linger”: My journey in the world of Disability

by Padmani Mendis

First Impressions and First Memories

But where are the trees? This was my first thought as the eight-seater circled the small airport at Gaborone, preparing to descend. Trees, green and water was what I was used to seeing in Asia and Europe. When I was preparing for my visit to Botswana, I had read that the Kalahari Desert was savanna on which grew grasses and small trees. Here I saw also that the ground was dry, yellow, sandy.

The airplane was small because the Gaborone airport at that time could not accommodate aircrafts that were any larger and certainly not jet aircraft. The route from Colombo required for me a transfer at Johannesburg to this eight-seater. During my first year of travel to Botswana I was fortunate that BOAC (later BA) – had a flight route that connected Hong Kong-Colombo-Johannesburg. This direct route was unprofitable and on my next visit I had to transit at either Bombay or Nairobi to get to Jo’burg. Five years later, Botswana had its own airport which they named the Sir Seretse Khama International Airport. I have not used this airport.

Sir Seretse Khama

The word Seretse Khama holds memories for me dating back to my youth. While at school and yet quite young, I saw in our morning newspaper, the “Ceylon Daily News,” what seemed to me to be an unusual photograph. It showed a couple standing arm-in-arm. The man was tall and dark with black frizzy hair. The woman was smaller with a light skin. I still see that photograph in my mind’s eye. The caption said that Seretse and Ruth Khama, formerly Ruth Williams, had married in London. The couple will be returning to Bechuanaland, a British Protectorate. Seretse Khama was the son of the former chief of Bechuanaland and was returning to be the chief himself.

This fascinated me, I know not why. I had to ask a cousin where Bechuanaland was, and she did not know either. Together we looked up the atlas I used at school to find out. Thereafter, I followed with interest what happened in that faraway country. I knew of the problems that were created by the British when Seretse returned to his country; and of the attempt by the British to have him and his English wife banished; how his people wanted him back and welcomed his wife with open arms; when it became the independent country Botswana and he became its prime minister; that the country was rich in diamonds, but was still desperately poor. Its diamonds were being mined by their neighbour, reaping the benefits of the growing diamond trade together with the benefits of apartheid for its white and wealthy minority, South Africa.

When Einar suggested that I start the CBR field trial in Botswana, I was just amazed. My reaction called for me to give an explanation to him and Gunnel. And here I was. Botswana was now a Republic and Sir Seretse Khama, GCB, KBE was its first elected President.When I related my story to Adelaide Kgosidinsti, my counterpart, she took me to visit Lady Ruth Khama. Sir Seretse’s health was failing rapidly. Ruth Khama lived in a villa-type residence, not large in appearance, with quite a few plants in the garden. I told her my story. She invited me to have tea with her.

Sir Desmond Tutu

Upon arrival in Gaborone I was met by someone from WHO and taken to check-in at the Holiday Inn Hotel. This was the only international hotel in town. There was another large hotel close to the station where most local people stayed. I too stayed there later on when Gunnel came to Botswana.While I was on the eight-seater from Jo’burg, I noticed a passenger walking down the aisle, greeting his fellow passengers. Going down to breakfast the next morning was difficult. I was alone – had never stayed in a posh hotel like this before. I was bashful and shy and probably showed it too. I sat down gingerly and ordered breakfast. Not much later came the sound of a booming voice.

Familiar from yesterday, on the plane. With a resounding “good morning” and a nod to each table, he sat down with a group.

After a while, seeing me, a lone strange woman in a saree, he came over to sit with me. He was wearing the collar indicative of his calling. Said his name was Desmond Tutu and asked if he could join me for breakfast. He talked with me at length. An exceptionally strong personality just oozed through his manner, his voice and his speech. There was no doubt that I was required to respond. Wanted to know where I was from, what my country was like, what I was doing, why I was in Gaborone, my plans and so on. He was gone the next day. The hotel people told me he had come to Jo’burg for the day to participate in a meeting. They thought he had gone on to Cape Town.

Very many years later Nalin and I went for a week’s holiday in Cape Town. On my birthday which fell on a Sunday we went to St. George’s Cathedral. Sir Desmond was Archbishop in Cape Town and St. George’s was his parish. He was preaching elsewhere that Sunday. So I did not meet Sir Desmond Tutu again. An anti-apartheid and human rights activist, he was the first black Archbishop of Cape Town, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, the Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism and the Gandhi Peace Prize. I had him in my memories and he enriched them.

Introduction to Botswana

The next morning I was sitting at the desk of the Chief Medical Officer of the Ministry of Health or MOH. He was a Norwegian and it was he who ran the health service in Botswana from the Ministry in Gaborone. There were very few Motswana – as the people of Botswana were called – medical doctors and these few had all studied abroad. Norwegians ran the entire health service. Seeds had been sown for a countrywide Primary Health Care Programme through the Regional Medical Officers of Health. This was said to be developing well and covering large parts of the country.

When he learned who I was and what my mission was, he sent for Adelaide Darling Kgosidinsti. While we waited until she arrived he attended to the collection of files on his table. He was obviously a very busy man and did not talk much.

Adelaide arrived. A lady with a large frame and distinctly commanding presence. She looked quite beautiful with her hair made neatly into a plait and folded round her head. Her skin, as was that of the people of her country, a distinctly lighter shade than those from the countries nearer the tropics like Kenya. Even Nigeria. Adelaide was introduced to me as the Commissioner of the Special Services Unit for the Handicapped. She was in charge of all disability prevention and rehabilitation services in the country. She was my National Counterpart.

The Chief Medical Officer and Adelaide had both met Einar. Einar had been to Botswana three years before me to plan for the setting up of CBR. The Chief Medical Officer instructed Adelaide to take me to Serowe and have me start on the task I had come to do for WHO. He did not show much interest in it. As I said earlier, he was obviously a very busy man. When Adelaide asked him how we should travel, he replied, “Take her on the train.”

Adelaide, I later came to know wanted to take me by road, which is how UN consultants are usually taken. But for me it was overnight on the train. I know not why. Adelaide slept most of the way. I had learned that she was not one given to chatting anyway. I was too excited to sleep. I enjoyed that train ride and repeated it many times, up and down to Serowe, a distance of about 300 kilometres.

However, there was but one experience that I did not look forward to on that train journey each way. I was required to change trains at Palapye, an important junction. This was around two in the morning and I had to wait near enough to an hour. At these times there was no one else around except for a few drunks weaving themselves around the platform. I was safe as long as I could stay away from their line of vision. There were occasions when I could not. Then it was always a game of hide and seek.

On our arrival early morning in Serowe a vehicle from the Regional Health Office met us. Our first visit had to be the Kgotla, the Office of the Chief to obtain his approval for my visit to his village and for my work here. The chief was in his colourful formal attire knowing that a foreigner was expected. Adelaide made sure that I followed all the proper protocols required by way of seating, greeting and conversing.

The Chief was most interested in how I was going to help the people of Serowe. He told me how families cared for their disabled members and explained a few traditional beliefs. He also told me that this was the largest village in Africa, with a population of 30,000 people. It was the home of the Bamangwato tribe and home to the Khama family. He was very proud of this, and naturally so.

Then the surprise – he said that he had someone from Sri Lanka working in his office.

He said I should meet him and had him sent for. In walked Mr. Swaminathan. He was the accountant in this small Tribal Office. That evening Mr. Swaminathan brought his wife together with his young daughter and son to visit me. We became friends. His children loved to visit me and play in my room. They were fascinated by my bedside clock and radio, obviously not having seen things used in the way I did. Here in a village on my first visit to Africa I meet a Sri Lankan. Mr. Swaminathan told me there was one more in Francistown, a large town in the north and another 30 or more in Gaborone. I met some of them on subsequent visits to Gaborone.

Some years later when I went to The Gambia, a small landlocked country in West Africa, I met around 30 Sri Lankans there too. In both places many were teachers, while others were accountants and engineers. More Sri Lankans were met when I went to the Bahamas on the other side of the world. We Sri Lankans had certainly spread ourselves around the globe.

Courtesy calls and finding a place to stay

After the Kgotla Adelaide took me to the social services office – it was a small one – to introduce me to Ethel Matiza, Social Service Officer or SSO for Serowe. Adelaide said she would be my counterpart in Serowe. We packed Ethel also into the pickup truck and went on to make a courtesy call to the Regional Medical Officer. He was from Hong Kong. When he heard that I planned to be in Serowe for three months, he invited me to stay with his wife and himself. They had a large house and plenty of space for a guest.

But Adelaide was quick to say thank you on my behalf. Because, she said, that she arranged with the director at the hospital to have me accommodated there. Which was just as well, because later I had a very small difference of opinion with the RMO. Being his guest would not have been of help in that. I learned a lesson here from Adelaide.

The director was waiting for us at the hospital. He showed me the room he had for me. The room had a bed and a dressing table. The mattress on the bed was bare with signs of long use. The windows had no curtains. I walked down a lengthy corridor to see the toilet and bathroom I would share. The bathroom had a bucket storing a little water. He then took me to the hospital kitchen and said I could prepare my meals here. I thanked him and asked if I could come back later?

Back in the vehicle, Adelaide said before I did that this was not suitable for me for a stay of three months. Ethel reminded Adelaide that there was just one option left – the Serowe Hotel. I said I did not need to see it, because that is where I would stay. Adelaide did not object too vociferously. I checked in at the Serowe Hotel and was allowed to choose my room – one of the only two that the hotel had. I chose the one with a window. Adelaide had never been here before.

Starting the field trial

We now planned with Ethel how we were to start the WHO field trial. The Regional Medical Officer had made it clear that we could have 15 Family Welfare Educators or FWEs – that is what the Primary Health Care workers were called – to participate in the trial. We could have these 15 for a maximum of three days, not more. Their routine work could not be interrupted. As soon as Ethel heard this from the RMO she sent off a message on the human telegraph line that the selected 15 should be at the community hall by 9 a.m. the next day. And they all were.

In the community hall the next morning Adelaide welcomed them, explaining to them that they had been asked to come to learn how to carry out this important task for the World Health Organisation in Geneva. And then she left for Gaborone to get back to her other duties. She came back to Serowe a couple of times to see how I was getting on. She went with us to the field to learn about CBR (Community Based Rehabilitation) in Botswana.

Ethel and I worked with the FWEs to prepare them for the work they were to undertake. We had enough Manuals to give one to each of them. We introduced them to all the components of the Manuals, discussing how each could be used; we had them describe and discuss the different disabled people – children and adults – they had met in their villages, the problems they had, and look for relevant parts of the Manual which they could use to give them advice on what they may do.

We set them problems to solve, case studies to discuss, turning the Manual this way and that, inside and out. Our aim, given these three short days, was to make them as familiar as possible with the actual physical handling of the Manual while learning it. At the same time as she was teaching with me, Ethel was also learning about the Manual. It was she who supervised the use of it after I was gone.

All in all, the entire workshop was essentially participatory and action-oriented. There was no other way. Serowe in Botswana was just one example of rural health and development and prioritising delivery needs. This was the reality in most developing countries.

This was the reality which CBR will have to use as an entry point. An essential first experience.Before the three days came to an end we made a programme with the FWEs. Ethel and I would visit them in their own areas of work. We asked them to get together in groups of three for this purpose. We would visit each group once a week. Before our visit, they would select disabled people in their areas who we would visit together. We would go to the homes of these people together, to continue their learning and ours in the use of the Manual.

And this field teaching and learning is what we did for the next 11 weeks in Botswana. It was at this time that the words of the Chinese Philosopher Lao Tzu came home to me with conviction:

“Go to the people. Live with them. Learn from them. Love them. Start with what they know. Build with what they have. But with the best leaders (teachers), when the work is done, the task accomplished, the people will say ‘We have done this ourselves’ “.

This has been the philosophy underlying my own CBR teaching from those first days in Botswana to this day.

Features

Ramadan 2026: Fasting hours around the world

The Muslim holy month of Ramadan is set to begin on February 18 or 19, depending on the sighting of the crescent moon.

During the month, which lasts 29 or 30 days, Muslims observing the fast will refrain from eating and drinking from dawn to dusk, typically for a period of 12 to 15 hours, depending on their location.

Muslims believe Ramadan is the month when the first verses of the Quran were revealed to the Prophet Muhammad more than 1,400 years ago.

The fast entails abstinence from eating, drinking, smoking and sexual relations during daylight hours to achieve greater “taqwa”, or consciousness of God.

Why does Ramadan start on different dates every year?

Ramadan begins 10 to 12 days earlier each year. This is because the Islamic calendar is based on the lunar Hijri calendar, with months that are 29 or 30 days long.

For nearly 90 percent of the world’s population living in the Northern Hemisphere, the number of fasting hours will be a bit shorter this year and will continue to decrease until 2031, when Ramadan will encompass the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year.

For fasting Muslims living south of the equator, the number of fasting hours will be longer than last year.

Because the lunar year is shorter than the solar year by 11 days, Ramadan will be observed twice in the year 2030 – first beginning on January 5 and then starting on December 26.

Fasting hours around the world

The number of daylight hours varies across the world.

Since it is winter in the Northern Hemisphere, this Ramadan, people living there will have the shortest fasts, lasting about 12 to 13 hours on the first day, with the duration increasing throughout the month.

People in southern countries like Chile, New Zealand, and South Africa will have the longest fasts, lasting about 14 to 15 hours on the first day. However, the number of fasting hours will decrease throughout the month.

[Aljazeera]

Features

The education crossroads:Liberating Sri Lankan classroom and moving ahead

Education reforms have triggered a national debate, and it is time to shift our focus from the mantra of memorising facts to mastering the art of thinking as an educational tool for the children of our land: the glorious future of Sri Lanka.

The 2026 National Education Reform Agenda is an ambitious attempt to transform a century-old colonial relic of rote-learning into a modern, competency-based system. Yet for all that, as the headlines oscillate between the “smooth rollout” of Grade 01 reforms and the “suspension of Grade 06 modules,” due to various mishaps, a deeper question remains: Do we truly and clearly understand how a human being learns?

Education is ever so often mistaken for the volume of facts a student can carry in his or her head until the day of an examination. In Sri Lanka the “Scholarship Exam” (Grade 05) and the O-Level/A-Level hurdles have created a culture where the brain is treated as a computer hard drive that stores data, rather than a superbly competent processor of information.

However, neuroscience and global success stories clearly project a different perspective. To reform our schools, we must first understand the journey of the human mind, from the first breath of infancy to the complex thresholds of adulthood.

The Architecture of the Early Mind: Infancy to Age 05

The journey begins not with a textbook, but with, in tennis jargon, a “serve and return” interaction. When a little infant babbles, and a parent responds with a smile or a word or a sentence, neural connections are forged at a rate of over one million per second. This is the foundation of cognitive architecture, the basis of learning. The baby learns that the parent is responsive to his or her antics and it is stored in his or her brain.

In Scandinavian countries like Finland and Norway, globally recognised and appreciated for their fantastic educational facilities, formal schooling does not even begin until age seven. Instead, the early years are dedicated to play-based learning. One might ask why? It is because neuroscience has clearly shown that play is the “work” of the child. Through play, children develop executive functions, responsiveness, impulse control, working memory, and mental flexibility.

In Sri Lanka, we often rush like the blazes on earth to put a pencil in the hand of a three-year-old, and then firmly demanding the child writes the alphabet. Contrast this with the United Kingdom’s “Birth to 5 Matters” framework. That initiative prioritises “self-regulation”, the ability to manage emotions and focus. A child who can regulate their emotions is a child who can eventually solve a quadratic equation. However, a child who is forced to memorise before they can play, often develops “school burnout” even before they hit puberty.

The Primary Years: Discovery vs. Dictation

As children move into the primary years (ages 06 to 12), the brain’s “neuroplasticity” is at its peak. Neuroplasticity refers to the malleability of the human brain. It is the brain’s ability to physically rewire its neural pathways in response to new information or the environment. This is the window where the “how” of learning becomes a lot more important than the “what” that the child should learn.

Singapore is often ranked number one in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores. It is a worldwide study conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that measures the scholastic performance of 15-year-old students in mathematics, science, and reading. It is considered to be the gold standard for measuring “education” because it does not test whether students can remember facts. Instead, it tests whether they can apply what they have learned to solve real-world problems; a truism that perfectly aligns with the argument that memorisation is not true or even valuable education. Singapore has moved away from its old reputation for “pressure-cooker” education. Their current mantra is “Teach Less, Learn More.” They have reduced the syllabus to give teachers room to facilitate inquiry. They use the “Concrete-Pictorial-Abstract” approach to mathematics, ensuring children understand the logic of numbers before they are asked to memorise formulae.

In Japan, the primary curriculum emphasises Moral Education (dotoku) and Special Activities (tokkatsu). Children learn to clean their own classrooms and serve lunch. This is not just about performing routine chores; it really is as far as you can get away from it. It is about learning collaboration and social responsibility. The Japanese are wise enough to understand that even an absolutely brilliant scientist who cannot work in a team is a liability to society.

In Sri Lanka, the current debate over the 2026 reforms centres on the “ABCDE” framework: Attendance, Belongingness, Cleanliness, Discipline, and English. While these are noble goals, we must be careful not to turn “Belongingness” into just another checkbox. True learning in the primary years happens when a child feels safe enough to ask “Why?” without the fear of being told “Because it is in the syllabus” or, in extreme cases, “It is not your job to question it.” Those who perpetrate such remarks need to have their heads examined, because in the developed world, the word “Why” is considered to be a very powerful expression, as it demands answers that involve human reasoning.

The Adolescent Brain: The Search for Meaning

Between ages 12 and 18, the brain undergoes a massive refashioning or “pruning” process. The prefrontal cortex of the human brain, the seat of reasoning, is still under construction. This is why teenagers are often impulsive but also capable of profound idealism. However, with prudent and gentle guiding, the very same prefrontal cortex can be stimulated to reach much higher levels of reasoning.

The USA and UK models, despite their flaws, have pioneered “Project-Based Learning” (PBL). Instead of sitting for a history lecture, students might be tasked with creating a documentary or debating a mock trial. This forces them to use 21st-century skills, like critical thinking, communication, and digital literacy. For example, memorising the date of the Battle of Danture is a low-level cognitive task. Google can do it in 0.02 seconds or less. However, analysing why the battle was fought, and its impact on modern Sri Lankan identity, is a high-level cognitive task. The Battle of Danture in 1594 is one of the most significant military victories in Sri Lankan history. It was a decisive clash between the forces of the Kingdom of Kandy, led by King Vimaladharmasuriya 1, and the Portuguese Empire, led by Captain-General Pedro Lopes de Sousa. It proved that a smaller but highly motivated force with a deep understanding of its environment could defeat a globally dominant superpower. It ensured that the Kingdom of Kandy remained independent for another 221 years, until 1815. Without this victory, Sri Lanka might have become a full Portuguese colony much earlier. Children who are guided to appreciate the underlying reasons for the victory will remember it and appreciate it forever. Education must move from the “What” to the “So What about it?“

The Great Fallacy: Why Memorisation is Not Education

The most dangerous myth in Sri Lankan education is that a “good memory” equals a “good education.” A good memory that remembers information is a good thing. However, it is vital to come to terms with the concept that understanding allows children to link concepts, reason, and solve problems. Memorisation alone just results in superficial learning that does not last.

Neuroscience shows that when we learn through rote recall, the information is stored in “silos.” It stays put in a store but cannot be applied to new contexts. However, when we learn through understanding, we build a web of associations, an omnipotent ability to apply it to many a variegated circumstance.

Interestingly, a hybrid approach exists in some countries. In East Asian systems, as found in South Korea and China, “repetitive practice” is often used, not for mindless rote, but to achieve “fluency.” Just as a pianist practices scales to eventually play a concerto with soul sounds incorporated into it, a student might practice basic arithmetic to free up “working memory” for complex physics. The key is that the repetition must lead to a “deep” approach, not a superficial or “surface” one.

Some Suggestions for Sri Lanka’s Reform Initiatives

The “hullabaloo” in Sri Lanka regarding the 2026 reforms is, in many ways, a healthy sign. It shows that the country cares. That is a very good thing. However, the critics have valid points.

* The Digital Divide: Moving towards “digital integration” is progressive, but if the burden of buying digital tablets and computers falls on parents in rural villages, we are only deepening the inequality and iniquity gap. It is our responsibility to ensure that no child is left behind, especially because of poverty. Who knows? That child might turn out to be the greatest scientist of all time.

* Teacher Empowerment: You cannot have “learner-centred education” without “independent-thinking teachers.” If our teachers are treated as “cogs in a machine” following rigid manuals from the National Institute of Education (NIE), the students will never learn to think for themselves. We need to train teachers to be the stars of guidance. Mistakes do not require punishments; they simply require gentle corrections.

* Breadth vs. Depth: The current reform’s tendency to increase the number of “essential subjects”, even up to 15 in some modules, ever so clearly risks overwhelming the cognitive and neural capacities of students. The result would be an “academic burnout.” We should follow the Scandinavian model of depth over breadth: mastering a few things deeply is much better than skimming the surface of many.

The Road to Adulthood

By the time a young adult reaches 21, his or her brain is almost fully formed. The goal of the previous 20 years should not have been to fill a “vessel” with facts, but to “kindle a fire” of curiosity.

The most successful adults in the 2026 global economy or science are not those who can recite the periodic table from memory. They are those who possess grit, persistence, adaptability, reasoning, and empathy. These are “soft skills” that are actually the hardest to teach. More importantly, they are the ones that cannot be tested in a three-hour hall examination with a pen and paper.

A personal addendum

As a Consultant Paediatrician with over half a century of experience treating children, including kids struggling with physical ailments as well as those enduring mental health crises in many areas of our Motherland, I have seen the invisible scars of our education system. My work has often been the unintended ‘landing pad’ for students broken by the relentless stresses of rote-heavy curricula and the rigid, unforgiving and even violently exhibited expectations of teachers. We are currently operating a system that prioritises the ‘average’ while failing the individual. This is a catastrophe that needs to be addressed.

In addition, and most critically, we lack a formal mechanism to identify and nurture our “intellectually gifted” children. Unlike Singapore’s dedicated Gifted Education Programme (GEP), which identifies and provides specialised care for high-potential learners from a very young age, our system leaves these bright minds to wither in the boredom of standard classrooms or, worse, treats their brilliance as a behavioural problem to be suppressed. Please believe me, we do have equivalent numbers of gifted child intellectuals as any other nation on Mother Earth. They need to be found and carefully nurtured, even with kid gloves at times.

All these concerns really break my heart as I am a humble product of a fantastic free education system that nurtured me all those years ago. This Motherland of mine gave me everything that I have today, and I have never forgotten that. It is the main reason why I have elected to remain and work in this country, despite many opportunities offered to me from many other realms. I decided to write this piece in a supposedly valiant effort to anticipate that saner counsel would prevail finally, and all the children of tomorrow will be provided with the very same facilities that were afforded to me, right throughout my career. Ever so sadly, the current system falls ever so far from it.

Conclusion: A Fervent Call to Action

If we want Sri Lanka to thrive, we must stop asking our children, “What did you learn today?” and start asking, “What did you learn to question today?“

Education reform is not just about changing textbooks or introducing modules. It is, very definitely, about changing our national mindset. We must learn to equally value the artist as much as the doctor, and the critical thinker as much as the top scorer in exams. Let us look to the world, to the play of the Finns, the discipline of the Japanese, and the inquiry of the British, and learn from them. But, and this is a BIG BUT…, let us build a system that is uniquely Sri Lankan. We need a system that makes absolutely sure that our children enjoy learning. We must ensure that it is one where every child, without leaving even one of them behind, from the cradle to the graduation cap, is seen not as a memory bank, but as a mind waiting to be set free.

by Dr B. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paed), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka

Journal of Child Health]

Section Editor, Ceylon Medical Journal

Features

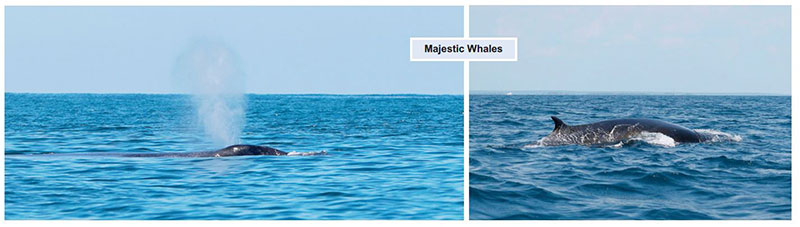

Giants in our backyard: Why Sri Lanka’s Blue Whales matter to the world

Standing on the southern tip of the island at Dondra Head, where the Indian Ocean stretches endlessly in every direction, it is difficult to imagine that beneath those restless blue waves lies one of the greatest wildlife spectacles on Earth.

Yet, according to Dr. Ranil Nanayakkara, Sri Lanka today is not just another tropical island with pretty beaches – it is one of the best places in the world to see blue whales, the largest animals ever to have lived on this planet.

“The waters around Sri Lanka are particularly good for blue whales due to a unique combination of geography and oceanographic conditions,” Dr. Nanayakkara told The Island. “We have a reliable and rich food source, and most importantly, a unique, year-round resident population.”

In a world where blue whales usually migrate thousands of kilometres between polar feeding grounds and tropical breeding areas, Sri Lanka offers something extraordinary – a non-migratory population of pygmy blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus indica) that stay around the island throughout the year. Instead of travelling to Antarctica, these giants simply shift their feeding grounds around the island, moving between the south and east coasts with the monsoons.

The secret lies beneath the surface. Seasonal monsoonal currents trigger upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water, which fuels massive blooms of phytoplankton. This, in turn, supports dense swarms of Sergestidae shrimps – tiny creatures that form the primary diet of Sri Lanka’s blue whales.

- “Engineers of the ocean system”

“Blue whales require dense aggregations of these shrimps to meet their massive energy needs,” Dr. Nanayakkara explained. “And the waters around Dondra Head and Trincomalee provide exactly that.”

Adding to this natural advantage is Sri Lanka’s narrow continental shelf. The seabed drops sharply into deep oceanic canyons just a few kilometres from the shore. This allows whales to feed in deep waters while remaining close enough to land to be observed from places like Mirissa and Trincomalee – a rare phenomenon anywhere in the world.

Dr. Nanayakkara’s journey into marine research began not in a laboratory, but in front of a television screen. As a child, he was captivated by the documentary Whales Weep Not by James R. Donaldson III – the first visual documentation of sperm and blue whales in Sri Lankan waters.

“That documentary planted the seed,” he recalled. “But what truly set my path was my first encounter with a sperm whale off Trincomalee. Seeing that animal surface just metres away was humbling. It made me realise that despite decades of conflict on land, Sri Lanka harbours globally significant marine treasures.”

Since then, his work has focused on cetaceans – from blue whales and sperm whales to tropical killer whales and elusive beaked whales. What continues to inspire him is both the scientific mystery and the human connection.

“These blue whales do not follow typical migration patterns. Their life cycles, communication and adaptability are still not fully understood,” he said. “And at the same time, seeing the awe in people’s eyes during whale watching trips reminds me why this work matters.”

Whale watching has become one of Sri Lanka’s fastest-growing tourism industries. On the south coast alone, thousands of tourists head out to sea every year in search of a glimpse of the giants. But Dr. Nanayakkara warned that without strict regulation, this boom could become a curse.

“We already have good guidelines – vessels must stay at least 100 metres away and maintain slow speeds,” he noted. “The problem is enforcement.”

Speaking to The Island, he stressed that Sri Lanka stands at a critical crossroads. “We can either become a global model for responsible ocean stewardship, or we can allow short-term economic interests to erode one of the most extraordinary marine ecosystems on the planet. The choice we make today will determine whether these giants continue to swim in our waters tomorrow.”

Beyond tourism, a far more dangerous threat looms over Sri Lanka’s whales – commercial shipping traffic. The main east-west shipping lanes pass directly through key blue whale habitats off the southern coast.

“The science is very clear,” Dr. Nanayakkara told The Island. “If we move the shipping lanes just 15 nautical miles south, we can reduce the risk of collisions by up to 95 percent.”

Such a move, however, requires political will and international cooperation through bodies like the International Maritime Organization and the International Whaling Commission.

“Ships travelling faster than 14 knots are far more likely to cause fatal injuries,” he added. “Reducing speeds to 10 knots in high-risk areas can cut fatal strikes by up to 90 percent. This is not guesswork – it is solid science.”

To most people, whales are simply majestic animals. But in ecological terms, they are far more than that – they are engineers of the ocean system itself.

Through a process known as the “whale pump”, whales bring nutrients from deep waters to the surface through their faeces, fertilising phytoplankton. These microscopic plants absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide, making whales indirect allies in the fight against climate change.

“When whales die and sink, they take all that carbon with them to the deep sea,” Dr. Nanayakkara said. “They literally lock carbon away for centuries.”

Even in death, whales create life. “Whale falls” – carcasses on the ocean floor – support unique deep-sea communities for decades.

“Protecting whales is not just about saving a species,” he said. “It is about protecting the ocean’s ability to function as a life-support system for the planet.”

For Dr. Nanayakkara, whales are not abstract data points – they are individuals with personalities and histories.

One of his most memorable encounters was with a female sperm whale nicknamed “Jaw”, missing part of her lower jaw.

“She surfaced right beside our boat, her massive eye level with mine,” he recalled. “In that moment, the line between observer and observed blurred. It was a reminder that these are sentient beings, not just research subjects.”

Another was with a tropical killer whale matriarch called “Notch”, who surfaced with her calf after a hunt.

“It felt like she was showing her offspring to us,” he said softly. “There was pride in her movement. It was extraordinary.”

Looking ahead, Dr. Nanayakkara envisions Sri Lanka as a global leader in a sustainable blue economy – where conservation and development go hand in hand.

“The ultimate goal is shared stewardship,” he told The Island. “When fishermen see healthy reefs as future income, and tour operators see protected whales as their greatest asset, conservation becomes everyone’s business.”

In the end, Sri Lanka’s greatest natural inheritance may not be its forests or mountains, but the silent giants gliding through its surrounding seas.

“Our ocean health is our greatest asset,” Dr. Nanayakkara said in conclusion. “If we protect it wisely, these whales will not just survive – they will define Sri Lanka’s place in the world.”

By Ifham Nizam

-

Life style2 days ago

Life style2 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Midweek Review6 days ago

Midweek Review6 days agoA question of national pride

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Business17 hours ago

Business17 hours agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka: