Features

Starting my nursing training in beautiful Birmingham

Excerpted from Memories that linger….

by Padmani Mendis

Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder

(Continued from last week)

There are some who knew Birmingham in the 1950s who would be amused to hear me say that Birmingham was beautiful. It was in physical appearance faded, dull and uninteresting. It was as devoid of culture as it was of green public spaces. It was the second largest city in the UK but it had not been bombed during World War II. As a result, no urgent rebuilding and accompanying redesigning had been called for.

The city stood as it had stood for decades before, spewing smoke from its many factories as the industrial heartland of England. That smoke, spreading out to rest on the many buildings in this congested location, and on the few trees that lay in its path, gave Birmingham a “forever grey” look. After I left Birmingham more than five years later, that look would go. Smoke-free fuel and modern design and architecture would invade. Birmingham would change with my departure and be truly beautiful to the eye.

My use of the adjective “beautiful” describes the city for the full and fulfilling life that it gave me during those five years and four months. The adjective “beautiful” I use to describe the inner heart of the city, deep within its deceptive exterior. It describes the people, their warmth, their friendliness and their unlimited kindness and the resulting impact those had on me. I do believe that much of these experiences lay with the fact that I was one of the first dark faces to be seen in the city.

Later, as with its appearance, so did these beautiful qualities of friendliness and kindness go into reverse gear. After I left, as well as architectural change, racial and ethnic tensions emerged. The Asian and Caribbean invasion had begun. Had I stayed much longer I would not have been able to describe Birmingham as being “beautiful”.

The journey to Birmingham is hazy in my mind. My brother Shatir had spent the night with Emdee in Holland Park. He had come to his bed-sit where I was by taxi and taken me to Paddington in time to catch the Dawn Express. But before we left the room he lifted his mattress and took out a hidden five-pound note which he would use to take me to Birmingham.

A Novice in a Hospital

The rest of the day, 64 years ago I recall as if it were yesterday. Here we were, Shatir and I, standing in the Matron’s office at the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital, or ROH, Northfield, in South Birmingham. Matron Galbraith was a buxom woman and one that looked formidable, sitting at her desk in her deep blue uniform and white flowing cap. This is the first I had seen of a hospital matron. I learned later that the Matron is the boss of the whole hospital. She ran the hospital and all its staff were answerable to her. The doctors looked after their medical responsibilities. They dared not venture beyond that. The hospital was the Matron’s business.

Without even knowing all that, I could not help but see that in her demeanour as she got up from her seat to come forward and welcome us. “Oh”, she said to Shatir, “You must be this young lady’s brother.” My mother had informed her before that he would bring me to the hospital, how and when. She was expecting us. “Well you can go back to London now. We will look after your sister.” I noticed she dare not say my name. Later she would ask me to pronounce it to her many times and learned to say “Wijeyesekera” quite well.

That desolate feeling I had in the pit of my stomach I neither felt before nor since. I was to be all alone in this strange place with these strange, unfriendly looking people. That I was petrified is too mild a word to use. My brother looked at me and turned to leave the room. Wanting to do that without delay I guess before either of us got too emotional.

As he left the room I ran after him and asked him for his pen. In the middle of all this I remembered that I had forgotten to bring a pen. What would I register my name with if I had to?

Matron was a professional through and through. No time wasted on smiles and trivialities. She called her secretary and asked her to take me to “Miss Burr” in the Nursing School. So the lady did, chatting as we went, feeling for my discomfort and trying to make me feel at home. Miss Burr was the Principal of the Nursing School of the ROH. As we were introduced she smiled in greeting, asked about my journey and whether, “my brother was on his way back to London”. It seemed that they had all been informed of the arrangements.

Miss Burr appeared to be much more pleasant than Matron, I thought. But later, after I had been in her awesome presence more than a couple of times, I found that Matron was an extremely kind and concerned sort of person. I think she had developed this exterior to go with her job.

How it Was in the School of Nursing

Before I knew it, I was standing in a classroom meeting a group of young women dressed in nurses’ uniforms – caps and all. I was in my saree selected specially for this day. The thought came to me that soon I would be just like one of them. The Nursing Course had really started on 20 October. I was a day late to join these young women who would soon be my colleagues and many of them later my friends. Some of us would be together for two years, while some of us would be together for another three. And a few of us still remain friends. Miss Burr then called out to “Nurse Turner” and “Nurse Smith”. A blonde and a brunette with shiny faces, both rather pretty, stood up.

She continued, “Could the two of you take Nurse Wijeyesekera to Mrs. McIntyre in the sewing room now? She is waiting for you and she will fit Nurse Wijeyesekera with her uniform, apron and cap. Then in the afternoon would you take her in to the city and show her where she could purchase her shoes and stockings and any other things that she may like? Don’t forget her tie-pins.” These would be required to hold my apron onto my uniform. The uniform was a pin-stripe in blue and white. Subdued as a nurse’s dress should be.

Off we went to the sewing room. Everybody called her Mrs. Mac it seemed, except the formal Miss Burr. She took all the measurements she required and then said to me, “Come in an hour dear and we will have all these ready for you.”

My response was the typical Ceylonese one – a shaking of the head from side to side to say yes. But in that part of the world this movement is taken as a no. So she said, “Oh she can’t understand English. Isn’t she lovlay?” That is how she said the word lovely in her “Brummie” for Birmingham, accent, At which Val and Jane took cover to hide their giggles. I was probably the first brown face that Mrs. Mac had seen. Also, the first saree for that matter. And it surely would have been so with many of my colleagues at the school and others around the hospital.

While we were being introduced in the classroom Miss Burr took care to point out to me that Lyda and Mahin both came from Persia and Barbara from Jamaica. I noticed that the two Persians were light skinned. So was Barbara because, she told me later, her father had Scottish ancestry and she had his skin colour. So I was the only one with a dark skin.

But then in Birmingham it mattered not at all. Except when, as I will share later, the dark skin was admired and liked and I was the beneficiary of special attention and kindness tinged with a distinct touch of favouritism.

Miss Burr had told us that it was the first time the hospital had accepted young ladies from foreign countries as student nurses. She said that both she and the hospital were happy to have us. She hoped we would be happy at “Woodlands”, as the ROH was referred to fondly.

Making Friends

It was Val Turner and Jane Smith of course who would show me the ways of being a student nurse at Woodlands. We would remain close friends for the rest of our training. What amazes me to this day, however, is that the four of us who had come from lands far away bonded with no delay. Before long the four of us would be inseparable. Lyda has now passed on. Mahin and Barbara and I still communicate frequently. More frequently now. Because earlier it had to be “Skype”. Now “WhatsApp” makes it so much easier. That is not to say that we do not communicate with the British friends we made during those early days in Birmingham. We do. But that special bond the three of us made in Birmingham, not forgetting Lyda, still holds firm. I will come back to them again when I share with you my journey in Jamaica thirty years or so later.

The difficulty of saying my name was too much. So my colleagues soon asked if they could shorten it to – guess what – Padi, just as I was called back home. From my first day at Woodlands as a student I was officially “Nurse’ and soon “Nurse Padi” to all who had to use my name, including the staff and patients at the ROH.

I was a Nurse. I had made a temporary stopover on my way to becoming a physiotherapist. More than that, I had entered the World of Disability. I had started on my life’s journey.

On being a Nurse

The next two years as a student nurse was the most intensive learning period of my life. Real life lessons to teach me to be the human being I wanted to be. Being a nurse in a hospital for disabled people as I was, taught me soon enough that my life’s learning until now was largely background. That background learning was the preliminary which pushed me forward. Pushed me into the practice of acquiring learning and that would take me to the core of knowing what I wanted to be and how to be that person.

Being a nurse to others would teach me to reach the depths of my humanity so that I could reach the depths of another’s distress. To learn the value of the life of each human being as she or he saw it; and the value of working with others at all times so that the person who was in need of care always had of the best. And I gobbled all this learning and put it into practice with a constant hunger for more. This is partly from whence came my enjoyment of being a nurse. And of being with disabled people.

Experiences of a Ward Nurse

After the preliminary two months in the school-learning the basic theory and practice of nursing, we went to work in the wards. I was to start in ward twelve, a long-stay ward for females. I can’t help thinking that Matron would have had me placed here. She would quite likely have thought that starting with old ladies was better for me than starting off with the men.

Sister Taylor, the ward sister, was young and active and brought to the ward the brightness and energy that it needed, as the ladies on long-stay were elderly or old. Most had fractured or arthritic hips that kept them in bed sometimes for six months or more, or even for the rest of their lives. Some had surgery to enable them to get out of bed sooner than others. Others had joint conditions about which nothing could be done. A few had had strokes as a result of which they could neither speak nor walk. Many of these patients would be bedridden forever. Many slept for the greater part of the day.

Mrs. Miller was one of these. She was 96 years old, had a broken hip about which nothing could be done, hardly communicated and spent most of the day sleeping. In keeping with her situation, she had a room to herself. She would not, or could not, cooperate with the nurses. This made nursing care very difficult. Yet she needed total care. She was reputed to be, “the most difficult patient in the ward”.

Sister Taylor soon found out how best she could use me. It was customary that, as soon as the lunch trolley was brought from the kitchen, Sister, with all the nurses walking alongside, would push the trolley along, she herself serving each patient’s portion on to a plate. A nurse would take that meal to a patient. When her trolley came to Mrs. Miller’s room she would call out, “Nurse Padi.” At this call I would have to emerge. With not another word she would hand the plate to me.

Feeding Mrs. Miller was no easy task. “Mrs. Miller, here is a spoonful. Open your mouth… Mrs. Miller, open your mouth,” I would repeat over and over again. Mrs. Miller would at last decide that she would. She would take in a few mouthfuls. And then, just as I said to myself, “Thank goodness she is cooperating today,” with no warning, Mrs. Miller would spit all the food she had accumulated in her mouth out at me.For a 96-year-old her aim was pretty good. My friends back home called me “a born optimist” and I was one now. Each day I thought I had learned to duck the volley. But then Mrs. Miller would cotton on to that and make sure to take better aim the next time. It became a game between us. Or rather, a competition.

Fernao Godhino

During my three months on Ward Six I made a special friend. His name was Fernao Godhino. He was 16 years old and had come all the way from Lisbon, Portugal to have his legs lengthened. Fernao was very short and he wanted to be closer to the height of other young boys of his age. We had an Orthopaedic Surgeon at the ROH who was world renowned for his success at doing this. I never saw Fernao standing up because he was confined to bed both when I arrived in the ward and three months later when I left it. Bill Scrase, the surgeon had already operated on Fernao.

The surgeon had cut across the tibia and fibula which are bones in the calf region of each leg. A machine was placed on the bed alongside Fernao’s legs. Each leg had fixed to it at the broken ends of the bones, two pins, each with a screw. The pins were connected to the machine in a way that a turn of a screw would move the ends of the bones on that leg apart. Sister had the task of turning the screws on each leg on alternate days. She was very fond of Fernao and carried out this task as gently as she could. But as you can imagine, every turn of the screw was sheer agony to Fernao. He would scream in pain. His screams touched all of us. His determination earned our respect and our love, staff and patients alike.

In me it seemed as though Fernao had found a soul-mate. Me away from home as he was. Much of the little free time I had was spent at his bed-side. We would talk about his home and mine. We would even sing softly together common songs that we both knew. But as this closeness grew so did a problem arise. Fernao started to tease me. It was like my brothers back home. He would tease me about me missing my home and family, about me never going back to see them and so on.

One day this was more than I could take. When he started to tease me, I asked him to stop. When he did not, my tears just flowed over. I just wept buckets. Perhaps I was weeping for both of us. What were the two of us doing here? Sister heard the rumpus. She came out of her office to put her arm around me and admonish Fernao. He was in the dog-house for the rest of the day. But the next day Fernao and I were friends. Fernao never teased me again.

Fernao, who to me seemed to be a youth like any other youth and no shorter than any other, has remained in my memory since then. Just like those others from my past who live in my memory. About two years ago I thought that it would be so good if I could speak with Fernao again. So I went to my computer and Googled “Godhino” in Lisbon.

There were a few popping up. I picked one who had made available his contact e-mail. I wrote to him about the Fernao Godhino I knew in Birmingham. “Do you by any chance know of him?” I asked. I got no response. I could not find Fernao again.

(To be continued)

Features

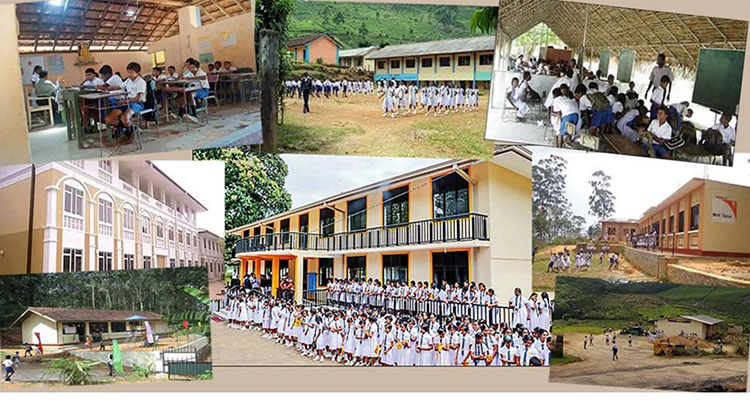

The education crossroads:Liberating Sri Lankan classroom and moving ahead

Education reforms have triggered a national debate, and it is time to shift our focus from the mantra of memorising facts to mastering the art of thinking as an educational tool for the children of our land: the glorious future of Sri Lanka.

The 2026 National Education Reform Agenda is an ambitious attempt to transform a century-old colonial relic of rote-learning into a modern, competency-based system. Yet for all that, as the headlines oscillate between the “smooth rollout” of Grade 01 reforms and the “suspension of Grade 06 modules,” due to various mishaps, a deeper question remains: Do we truly and clearly understand how a human being learns?

Education is ever so often mistaken for the volume of facts a student can carry in his or her head until the day of an examination. In Sri Lanka the “Scholarship Exam” (Grade 05) and the O-Level/A-Level hurdles have created a culture where the brain is treated as a computer hard drive that stores data, rather than a superbly competent processor of information.

However, neuroscience and global success stories clearly project a different perspective. To reform our schools, we must first understand the journey of the human mind, from the first breath of infancy to the complex thresholds of adulthood.

The Architecture of the Early Mind: Infancy to Age 05

The journey begins not with a textbook, but with, in tennis jargon, a “serve and return” interaction. When a little infant babbles, and a parent responds with a smile or a word or a sentence, neural connections are forged at a rate of over one million per second. This is the foundation of cognitive architecture, the basis of learning. The baby learns that the parent is responsive to his or her antics and it is stored in his or her brain.

In Scandinavian countries like Finland and Norway, globally recognised and appreciated for their fantastic educational facilities, formal schooling does not even begin until age seven. Instead, the early years are dedicated to play-based learning. One might ask why? It is because neuroscience has clearly shown that play is the “work” of the child. Through play, children develop executive functions, responsiveness, impulse control, working memory, and mental flexibility.

In Sri Lanka, we often rush like the blazes on earth to put a pencil in the hand of a three-year-old, and then firmly demanding the child writes the alphabet. Contrast this with the United Kingdom’s “Birth to 5 Matters” framework. That initiative prioritises “self-regulation”, the ability to manage emotions and focus. A child who can regulate their emotions is a child who can eventually solve a quadratic equation. However, a child who is forced to memorise before they can play, often develops “school burnout” even before they hit puberty.

The Primary Years: Discovery vs. Dictation

As children move into the primary years (ages 06 to 12), the brain’s “neuroplasticity” is at its peak. Neuroplasticity refers to the malleability of the human brain. It is the brain’s ability to physically rewire its neural pathways in response to new information or the environment. This is the window where the “how” of learning becomes a lot more important than the “what” that the child should learn.

Singapore is often ranked number one in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores. It is a worldwide study conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that measures the scholastic performance of 15-year-old students in mathematics, science, and reading. It is considered to be the gold standard for measuring “education” because it does not test whether students can remember facts. Instead, it tests whether they can apply what they have learned to solve real-world problems; a truism that perfectly aligns with the argument that memorisation is not true or even valuable education. Singapore has moved away from its old reputation for “pressure-cooker” education. Their current mantra is “Teach Less, Learn More.” They have reduced the syllabus to give teachers room to facilitate inquiry. They use the “Concrete-Pictorial-Abstract” approach to mathematics, ensuring children understand the logic of numbers before they are asked to memorise formulae.

In Japan, the primary curriculum emphasises Moral Education (dotoku) and Special Activities (tokkatsu). Children learn to clean their own classrooms and serve lunch. This is not just about performing routine chores; it really is as far as you can get away from it. It is about learning collaboration and social responsibility. The Japanese are wise enough to understand that even an absolutely brilliant scientist who cannot work in a team is a liability to society.

In Sri Lanka, the current debate over the 2026 reforms centres on the “ABCDE” framework: Attendance, Belongingness, Cleanliness, Discipline, and English. While these are noble goals, we must be careful not to turn “Belongingness” into just another checkbox. True learning in the primary years happens when a child feels safe enough to ask “Why?” without the fear of being told “Because it is in the syllabus” or, in extreme cases, “It is not your job to question it.” Those who perpetrate such remarks need to have their heads examined, because in the developed world, the word “Why” is considered to be a very powerful expression, as it demands answers that involve human reasoning.

The Adolescent Brain: The Search for Meaning

Between ages 12 and 18, the brain undergoes a massive refashioning or “pruning” process. The prefrontal cortex of the human brain, the seat of reasoning, is still under construction. This is why teenagers are often impulsive but also capable of profound idealism. However, with prudent and gentle guiding, the very same prefrontal cortex can be stimulated to reach much higher levels of reasoning.

The USA and UK models, despite their flaws, have pioneered “Project-Based Learning” (PBL). Instead of sitting for a history lecture, students might be tasked with creating a documentary or debating a mock trial. This forces them to use 21st-century skills, like critical thinking, communication, and digital literacy. For example, memorising the date of the Battle of Danture is a low-level cognitive task. Google can do it in 0.02 seconds or less. However, analysing why the battle was fought, and its impact on modern Sri Lankan identity, is a high-level cognitive task. The Battle of Danture in 1594 is one of the most significant military victories in Sri Lankan history. It was a decisive clash between the forces of the Kingdom of Kandy, led by King Vimaladharmasuriya 1, and the Portuguese Empire, led by Captain-General Pedro Lopes de Sousa. It proved that a smaller but highly motivated force with a deep understanding of its environment could defeat a globally dominant superpower. It ensured that the Kingdom of Kandy remained independent for another 221 years, until 1815. Without this victory, Sri Lanka might have become a full Portuguese colony much earlier. Children who are guided to appreciate the underlying reasons for the victory will remember it and appreciate it forever. Education must move from the “What” to the “So What about it?“

The Great Fallacy: Why Memorisation is Not Education

The most dangerous myth in Sri Lankan education is that a “good memory” equals a “good education.” A good memory that remembers information is a good thing. However, it is vital to come to terms with the concept that understanding allows children to link concepts, reason, and solve problems. Memorisation alone just results in superficial learning that does not last.

Neuroscience shows that when we learn through rote recall, the information is stored in “silos.” It stays put in a store but cannot be applied to new contexts. However, when we learn through understanding, we build a web of associations, an omnipotent ability to apply it to many a variegated circumstance.

Interestingly, a hybrid approach exists in some countries. In East Asian systems, as found in South Korea and China, “repetitive practice” is often used, not for mindless rote, but to achieve “fluency.” Just as a pianist practices scales to eventually play a concerto with soul sounds incorporated into it, a student might practice basic arithmetic to free up “working memory” for complex physics. The key is that the repetition must lead to a “deep” approach, not a superficial or “surface” one.

Some Suggestions for Sri Lanka’s Reform Initiatives

The “hullabaloo” in Sri Lanka regarding the 2026 reforms is, in many ways, a healthy sign. It shows that the country cares. That is a very good thing. However, the critics have valid points.

* The Digital Divide: Moving towards “digital integration” is progressive, but if the burden of buying digital tablets and computers falls on parents in rural villages, we are only deepening the inequality and iniquity gap. It is our responsibility to ensure that no child is left behind, especially because of poverty. Who knows? That child might turn out to be the greatest scientist of all time.

* Teacher Empowerment: You cannot have “learner-centred education” without “independent-thinking teachers.” If our teachers are treated as “cogs in a machine” following rigid manuals from the National Institute of Education (NIE), the students will never learn to think for themselves. We need to train teachers to be the stars of guidance. Mistakes do not require punishments; they simply require gentle corrections.

* Breadth vs. Depth: The current reform’s tendency to increase the number of “essential subjects”, even up to 15 in some modules, ever so clearly risks overwhelming the cognitive and neural capacities of students. The result would be an “academic burnout.” We should follow the Scandinavian model of depth over breadth: mastering a few things deeply is much better than skimming the surface of many.

The Road to Adulthood

By the time a young adult reaches 21, his or her brain is almost fully formed. The goal of the previous 20 years should not have been to fill a “vessel” with facts, but to “kindle a fire” of curiosity.

The most successful adults in the 2026 global economy or science are not those who can recite the periodic table from memory. They are those who possess grit, persistence, adaptability, reasoning, and empathy. These are “soft skills” that are actually the hardest to teach. More importantly, they are the ones that cannot be tested in a three-hour hall examination with a pen and paper.

A personal addendum

As a Consultant Paediatrician with over half a century of experience treating children, including kids struggling with physical ailments as well as those enduring mental health crises in many areas of our Motherland, I have seen the invisible scars of our education system. My work has often been the unintended ‘landing pad’ for students broken by the relentless stresses of rote-heavy curricula and the rigid, unforgiving and even violently exhibited expectations of teachers. We are currently operating a system that prioritises the ‘average’ while failing the individual. This is a catastrophe that needs to be addressed.

In addition, and most critically, we lack a formal mechanism to identify and nurture our “intellectually gifted” children. Unlike Singapore’s dedicated Gifted Education Programme (GEP), which identifies and provides specialised care for high-potential learners from a very young age, our system leaves these bright minds to wither in the boredom of standard classrooms or, worse, treats their brilliance as a behavioural problem to be suppressed. Please believe me, we do have equivalent numbers of gifted child intellectuals as any other nation on Mother Earth. They need to be found and carefully nurtured, even with kid gloves at times.

All these concerns really break my heart as I am a humble product of a fantastic free education system that nurtured me all those years ago. This Motherland of mine gave me everything that I have today, and I have never forgotten that. It is the main reason why I have elected to remain and work in this country, despite many opportunities offered to me from many other realms. I decided to write this piece in a supposedly valiant effort to anticipate that saner counsel would prevail finally, and all the children of tomorrow will be provided with the very same facilities that were afforded to me, right throughout my career. Ever so sadly, the current system falls ever so far from it.

Conclusion: A Fervent Call to Action

If we want Sri Lanka to thrive, we must stop asking our children, “What did you learn today?” and start asking, “What did you learn to question today?“

Education reform is not just about changing textbooks or introducing modules. It is, very definitely, about changing our national mindset. We must learn to equally value the artist as much as the doctor, and the critical thinker as much as the top scorer in exams. Let us look to the world, to the play of the Finns, the discipline of the Japanese, and the inquiry of the British, and learn from them. But, and this is a BIG BUT…, let us build a system that is uniquely Sri Lankan. We need a system that makes absolutely sure that our children enjoy learning. We must ensure that it is one where every child, without leaving even one of them behind, from the cradle to the graduation cap, is seen not as a memory bank, but as a mind waiting to be set free.

by Dr B. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paed), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka

Journal of Child Health]

Section Editor, Ceylon Medical Journal

Features

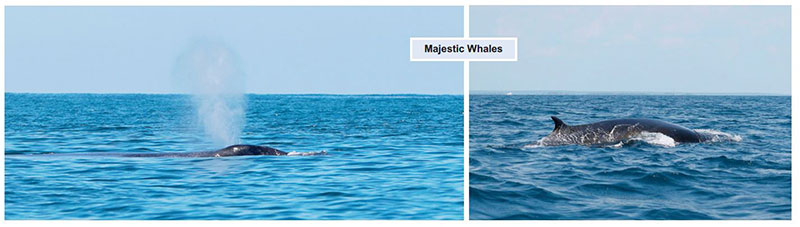

Giants in our backyard: Why Sri Lanka’s Blue Whales matter to the world

Standing on the southern tip of the island at Dondra Head, where the Indian Ocean stretches endlessly in every direction, it is difficult to imagine that beneath those restless blue waves lies one of the greatest wildlife spectacles on Earth.

Yet, according to Dr. Ranil Nanayakkara, Sri Lanka today is not just another tropical island with pretty beaches – it is one of the best places in the world to see blue whales, the largest animals ever to have lived on this planet.

“The waters around Sri Lanka are particularly good for blue whales due to a unique combination of geography and oceanographic conditions,” Dr. Nanayakkara told The Island. “We have a reliable and rich food source, and most importantly, a unique, year-round resident population.”

In a world where blue whales usually migrate thousands of kilometres between polar feeding grounds and tropical breeding areas, Sri Lanka offers something extraordinary – a non-migratory population of pygmy blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus indica) that stay around the island throughout the year. Instead of travelling to Antarctica, these giants simply shift their feeding grounds around the island, moving between the south and east coasts with the monsoons.

The secret lies beneath the surface. Seasonal monsoonal currents trigger upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water, which fuels massive blooms of phytoplankton. This, in turn, supports dense swarms of Sergestidae shrimps – tiny creatures that form the primary diet of Sri Lanka’s blue whales.

- “Engineers of the ocean system”

“Blue whales require dense aggregations of these shrimps to meet their massive energy needs,” Dr. Nanayakkara explained. “And the waters around Dondra Head and Trincomalee provide exactly that.”

Adding to this natural advantage is Sri Lanka’s narrow continental shelf. The seabed drops sharply into deep oceanic canyons just a few kilometres from the shore. This allows whales to feed in deep waters while remaining close enough to land to be observed from places like Mirissa and Trincomalee – a rare phenomenon anywhere in the world.

Dr. Nanayakkara’s journey into marine research began not in a laboratory, but in front of a television screen. As a child, he was captivated by the documentary Whales Weep Not by James R. Donaldson III – the first visual documentation of sperm and blue whales in Sri Lankan waters.

“That documentary planted the seed,” he recalled. “But what truly set my path was my first encounter with a sperm whale off Trincomalee. Seeing that animal surface just metres away was humbling. It made me realise that despite decades of conflict on land, Sri Lanka harbours globally significant marine treasures.”

Since then, his work has focused on cetaceans – from blue whales and sperm whales to tropical killer whales and elusive beaked whales. What continues to inspire him is both the scientific mystery and the human connection.

“These blue whales do not follow typical migration patterns. Their life cycles, communication and adaptability are still not fully understood,” he said. “And at the same time, seeing the awe in people’s eyes during whale watching trips reminds me why this work matters.”

Whale watching has become one of Sri Lanka’s fastest-growing tourism industries. On the south coast alone, thousands of tourists head out to sea every year in search of a glimpse of the giants. But Dr. Nanayakkara warned that without strict regulation, this boom could become a curse.

“We already have good guidelines – vessels must stay at least 100 metres away and maintain slow speeds,” he noted. “The problem is enforcement.”

Speaking to The Island, he stressed that Sri Lanka stands at a critical crossroads. “We can either become a global model for responsible ocean stewardship, or we can allow short-term economic interests to erode one of the most extraordinary marine ecosystems on the planet. The choice we make today will determine whether these giants continue to swim in our waters tomorrow.”

Beyond tourism, a far more dangerous threat looms over Sri Lanka’s whales – commercial shipping traffic. The main east-west shipping lanes pass directly through key blue whale habitats off the southern coast.

“The science is very clear,” Dr. Nanayakkara told The Island. “If we move the shipping lanes just 15 nautical miles south, we can reduce the risk of collisions by up to 95 percent.”

Such a move, however, requires political will and international cooperation through bodies like the International Maritime Organization and the International Whaling Commission.

“Ships travelling faster than 14 knots are far more likely to cause fatal injuries,” he added. “Reducing speeds to 10 knots in high-risk areas can cut fatal strikes by up to 90 percent. This is not guesswork – it is solid science.”

To most people, whales are simply majestic animals. But in ecological terms, they are far more than that – they are engineers of the ocean system itself.

Through a process known as the “whale pump”, whales bring nutrients from deep waters to the surface through their faeces, fertilising phytoplankton. These microscopic plants absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide, making whales indirect allies in the fight against climate change.

“When whales die and sink, they take all that carbon with them to the deep sea,” Dr. Nanayakkara said. “They literally lock carbon away for centuries.”

Even in death, whales create life. “Whale falls” – carcasses on the ocean floor – support unique deep-sea communities for decades.

“Protecting whales is not just about saving a species,” he said. “It is about protecting the ocean’s ability to function as a life-support system for the planet.”

For Dr. Nanayakkara, whales are not abstract data points – they are individuals with personalities and histories.

One of his most memorable encounters was with a female sperm whale nicknamed “Jaw”, missing part of her lower jaw.

“She surfaced right beside our boat, her massive eye level with mine,” he recalled. “In that moment, the line between observer and observed blurred. It was a reminder that these are sentient beings, not just research subjects.”

Another was with a tropical killer whale matriarch called “Notch”, who surfaced with her calf after a hunt.

“It felt like she was showing her offspring to us,” he said softly. “There was pride in her movement. It was extraordinary.”

Looking ahead, Dr. Nanayakkara envisions Sri Lanka as a global leader in a sustainable blue economy – where conservation and development go hand in hand.

“The ultimate goal is shared stewardship,” he told The Island. “When fishermen see healthy reefs as future income, and tour operators see protected whales as their greatest asset, conservation becomes everyone’s business.”

In the end, Sri Lanka’s greatest natural inheritance may not be its forests or mountains, but the silent giants gliding through its surrounding seas.

“Our ocean health is our greatest asset,” Dr. Nanayakkara said in conclusion. “If we protect it wisely, these whales will not just survive – they will define Sri Lanka’s place in the world.”

By Ifham Nizam

Features

Prof. Tissa Vitarana: A scientist–statesman who changed the course of Sri Lanka’s innovation journey

Sri Lanka awoke on the morning of 13 February, 2026, to the quiet passing of Professor Tissa Vitarana at his home in Nawala. With him departs not only a towering figure in science and public life, but also a rare national conscience—one that insisted, often against prevailing currents, that science, technology, and innovation must serve the people, the nation, and the future.

I had known Professor Vitarana from my early childhood and vividly recall his visits to our home in the 1970s and 1980s to meet my father, the late Mr. G. V. S. de Silva. At the time, I could not have imagined that he would later become one of the most pivotal teachers and mentors in my life. My first professional engagement with him came in 1986, when I was assigned to the Medical Research Institute (MRI) by the Postgraduate Institute of Medicine (PGIM) for my postgraduate training in microbiology. That encounter marked the beginning of a professional journey shaped profoundly by his guidance.

To me, he was first a teacher, then a mentor, later a colleague and a friend—and always a source of intellectual provocation and moral steadiness. My own professional life—its direction, ambitions, and even its internal debates—was deeply influenced by my association with him. I was privileged to work closely with Prof. Vitarana during what can only be described as the most consequential period in the evolution of Sri Lanka’s science and innovation ecosystem since independence.

Teacher and reformer of medical education

Before Prof. Vitarana became a national figure in science policy, he was, at heart, a scientist and an academic institution builder. In 1995, shortly after his retirement from the MRI, he was appointed Founder Professor of Microbiology at the newly established Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura. The faculty was young, resources were limited, and expectations were high—but he saw in it an opportunity not to replicate inherited models, but to rethink them.

In 1996, I joined the faculty as Senior Lecturer in Microbiology, beginning a long and formative professional partnership. Working closely together, we shared a conviction that medical microbiology education in Sri Lanka needed to move decisively beyond the traditional organism-centred—often disparagingly termed “bug-based”—approach. We believed instead in a disease-oriented curriculum, integrating pathogens with clinical presentation, diagnosis, epidemiology, and public-health relevance.

Implementing this shift was far from easy. It challenged entrenched academic traditions and demanded both pedagogical courage and strong institutional backing. Prof. Vitarana provided both. With his guidance and support, the Faculty of Medical Sciences at Jayewardenepura became the first in Sri Lanka to introduce a fully comprehensive disease-oriented microbiology curriculum—an approach that subsequently influenced teaching practices across other medical faculties. In retrospect, this episode foreshadowed the principles that would later define his national work: clarity of vision, patience in execution, and the willingness to question inherited structures.

A scientist who entered politics—without abandoning science

A Fellow of the National Academy of Sciences of Sri Lanka, Prof. Vitarana was, unequivocally, a scientist. Trained in medicine, bacteriology, and virology, he built an international reputation through his work at the MRI, which he later led as Director. His scientific credentials were never in doubt. Yet history will remember him most distinctly as a politician who refused to abandon science, even when politics would have made that the easier choice.

When he entered Parliament and later assumed office as Minister of Science and Technology, Sri Lanka’s science system was fragmented, underfunded, and largely disconnected from national development. Research institutions operated in silos; universities engaged minimally with industry; and innovation was barely part of the national vocabulary. Public investment in R&D was low, private-sector participation negligible, and science was often viewed as a luxury rather than a necessity.

Prof. Vitarana recognised this reality clearly—and refused to accept it as inevitable.

The courage to think systemically

One of his most enduring contributions was his insistence that science could not advance in isolation. It required strategy, coordination, institutions, and—above all—political will. This conviction shaped every major initiative he championed.

Under his leadership and encouragement, Sri Lanka embarked on the National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI)—a bold and, at the time, audacious decision, taken amidst civil war and severe fiscal constraints. The idea was simple yet transformative: instead of dispersing scarce scientific resources across multiple institutions, Sri Lanka would converge them into a single, high-end strategic platform, built through a public–private partnership and aligned with industry needs.

This vision led to the establishment of the Sri Lanka Institute of Nanotechnology (SLINTEC)—an institution that has since become a symbol of what Sri Lankan science can achieve when provided autonomy, infrastructure, and purpose. SLINTEC’s early successes—US patents, technology licensing, international recognition, and growing private-sector confidence—did more than validate a model; they reshaped mindsets. Policymakers began to believe. Industry began to invest. Young scientists began to stay.

That catalytic impact is now embedded in Sri Lanka’s institutional memory.

Strategy before slogans

Prof. Vitarana was never content with isolated success stories. He understood that without a national framework, innovation would remain episodic and fragile. This belief culminated in the formulation of Sri Lanka’s first National Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) Strategy, approved by Cabinet in 2010 and subsequently presented to Parliament.

The strategy was pragmatic, time-bound, and unflinchingly honest about national weaknesses. It set measurable targets, linked science to economic transformation, and recognised that innovation must serve not only growth, but also equity and sustainability.

To translate strategy into action, Prof. Vitarana supported the establishment of the Coordinating Secretariat for Science, Technology and Innovation (COSTI)—designed to break institutional silos, align ministries, and ensure that public investment in research translated into tangible societal benefit. Despite bureaucratic resistance and political turbulence, COSTI endured and eventually evolved into the National Innovation Agency (NIA), formalised through an Act of Parliament. Few initiatives better illustrate his patience, persistence, and long-term vision.

From nanotechnology to biotechnology: extending the vision

Prof. Vitarana’s system-level thinking did not stop with nanotechnology. As our work through COSTI matured, he urged us to look further—to biotechnology as a strategic national capability, capable of leveraging Sri Lanka’s rich biological resources and scientific talent. In this context, he conceptualised the Sri Lanka Institute of Biotechnology (SLIBTEC) as a complementary pillar to SLINTEC, anchoring advanced biotechnology research, translation, and commercialisation within a coherent national framework.

Technology to the village: the moral core of his politics

Among his many achievements, Prof. Vitarana often spoke most passionately about the Vidatha programme. This was not about advanced laboratories or international patents; it was about taking technology to the village, empowering micro- and small-scale enterprises, and ensuring that innovation did not remain an urban or elite privilege.

Although I was not directly involved in its implementation, we had many discussions on Vidatha. He welcomed critical feedback and remained unwavering in his belief that science must touch everyday life. Vidatha was, in many ways, the moral anchor of his science policy—an expression of his deep commitment to social justice and inclusive development.

Quality, credibility, and trust in science

What distinguished Prof. Vitarana was not only his appetite for innovation, but his insistence on quality and credibility. He believed deeply that science must earn public trust. I clearly recall his firm insistence on introducing accreditation for medical and testing laboratories, long before quality assurance became fashionable policy language. I was privileged to be part of those early efforts.

This conviction culminated in the establishment of the Sri Lanka Accreditation Board (SLAB), strengthening the integrity of scientific and technical services across the country. For Prof. Vitarana, accreditation was not bureaucracy—it was the backbone of trust.

The unfinished dreams

Not all our shared visions came to fruition. We collectively envisioned the establishment of a National Science Centre cum explaratorium —a space where science would meet society, curiosity would be nurtured, and scientific literacy cultivated across generations. Plans were drawn, concepts refined, and momentum built. Yet political shifts, bureaucratic inertia, and changing priorities meant the project never materialised.

Prof. Vitarana accepted these disappointments with remarkable equanimity. He understood that nation-building is rarely linear and that progress often outlives its original champions.

A mentor who trusted, not micromanaged

On a personal level, Prof. Vitarana gave me something invaluable: intellectual freedom. He trusted people, delegated responsibility, and never micromanaged. When obstacles arose—often from the bureaucracy or the Treasury—he stood as a buffer, absorbing pressure so others could continue their work.

There were moments of frustration. He loved politics—perhaps more than science—and that occasionally irritated me. Our philosophical disagreements were real and sometimes sharp, shaped by his political ideology and my own Buddhist-influenced thinking. Yet they were always respectful, often enriching, and never diminished the mutual regard we shared.

A legacy that endures

Today, institutions such as SLINTEC, COSTI/NIA, SLIBTEC, and SLAB stand not merely as organisations, but as embodied ideas—proof that Sri Lanka can think strategically, act boldly, and build sustainably.

Prof. Tissa Vitarana’s greatest legacy may well be this: he convinced a generation that Sri Lankan scientists, technologists, and entrepreneurs are capable of excellence—provided they are trusted, supported, and allowed to work within a conducive ecosystem. He shifted national conversations, altered institutional trajectories, and left an imprint that will outlast political cycles.

I shall miss him deeply—not only for his guidance and steadfast support, but also for the arguments, the laughter, the impatience, and the shared hope that Sri Lanka could do better, think bigger, and act wiser.

May his journey through sansara be short!

And may the nation he served with such conviction remember, protect, and build upon the foundations he laid!

by Sirimali Fernando

Former Science Advisor to the Minister of Science and Technology

Former Chairperson, National Science Foundation

Former CEO, COSTI

Founder Board Member – SLINTEC

Founder Board Member – SLAB

Current Board Member – SLIBTEC

Former Senior Professor of Microbiology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, USJP

-

Life style1 day ago

Life style1 day agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Midweek Review5 days ago

Midweek Review5 days agoA question of national pride

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

Midweek Review5 days ago

Midweek Review5 days agoTheatre and Anthropocentrism in the age of Climate Emergency