Features

Roaming the world to tap global experience on peace seeking and Gamini D’s assassination

Douglas Devananda took to his heels in Manila fearing an LTTE gunman was trailing us

1994 saw a new crop of MPs who had political knowledge outside their usual electorate concerns. Most of them had a wider vision than merely serving as providers of food stamps, roads and various other handouts to their voters. International Alert first organized a seminar for about 25 of them in the island of Crete in Greece. Apart from MPs from the SLFP and UNP, representatives of minority communities in Parliament were invited for this seminar.

We were to be introduced to the South African dialogue which resulted in the ending of Apartheid and the establishment of the new multi-racial South African nation under Nelson Mandela. The leader and facilitator of this dialogue was Pravin Gordan, then a senior official of the new republic who was later to be South Africa’s Finance Minister under President M’beki.

Among the participants I remember Rukman Senanayake, Mahinda Samarasinghe ,AnuraYapa, Dullas Alahapperuma,Dilan Perera, Karunasena Kodituwakku and Imtiaz Bakeer Markar. Minority parties were represented by Douglas Devananda, Rauf Hakeem and Hisbullah. The participation of Hisbullah created a problem for us. We were en route to Crete via Frankfurt and Athens. Since Hisbullah was the unofficial leader of our group – he was the Deputy Minister of Telecommunications and the only holder of ministerial rank in the delegation – his passport was submitted first to passport control at Frankfurt Airport.

The passport officer – obviously a newcomer – saw stars when he read Hisbullahs name. He shepherded all of us to a room, shut the door and ran to his superior. An experienced officer came down after some time to find that our motley crew of middle aged parliamentarians were certainly not terrorists. He apologized, stamped our transit visas and put us on the waiting plane to Athens. After that we made sure that Hisbullah’s passport was the last in our bundle of documents. There is an interesting post script to our visit to Greece.

A few days into the meeting we got the startling news about the bombing of the Central Bank in Colombo by the LTTE. We were desperate to get information from Colombo. Fortunately Hisbullah – the Deputy Minister of Telecommunications, was in our delegation and he arranged for all of us to get calls to Colombo. That was particularly important for me because my elder daughter Ramanika was working in the American Express Bank which was across the street from the Central Bank. I spoke to her on the telephone and was relieved to hear that she was safe. However one of her colleagues who was on the ground floor of the bank had been killed in the blast.

Belfast

Our next tour was to Northern Ireland. We all looked forward to this tour as Irish problems were very much in the news then with bombs exploding in London and an attack on the British Parliament itself. Lord Mountbatten and members of his family were killed while holidaying in an Irish village. Strict security measures were in force when we landed in Belfast where the inner city was a “no go zone”. We were whisked away to Bellamina Hotel which was quite far from the city.

On this occasion we were introduced to the leaders of the different contending groups who talked to us about their perceptions of a negotiated settlement. The Irish Catholics who dominated the countryside described their plight as victims of British colonialism. The Scots and English had invaded their land and after bitter battles subjugated them and held them as colonial subjects as in other parts of the globe. Large swathes of fertile land had been acquired by those invaders and we could see the big colonial mansions of the Irish Protestant aristocracy as we drove past the incredibly well maintained parks and greens.

The Protestants who were called “loyalists”as they were loyal to England and English royalty, were economically better off. They initially resorted to violence to maintain their dominance forcing retaliation by the Catholics. Their clashes in Belfast and Londonderry were parts of legends that kept them apart. But by far the main reason for the ethnic conflict was religion. The Sinn Fienn was the political party which represented the Catholics while the IRA was its military arm. The Catholics were larger in number and were encouraged by their coreligionists who were south of the border as the Irish Republic, with the legendary city of Dublin as its capital.

On the other hand the loyalists were fanatics who had contempt for the Catholics who had served as workers in their estates in the past. The status of these virtual slaves was low. Many had to emigrate to the United States during the potato famine to keep alive. The US Irish – including the Kennedys, Clintons and Bidens – were of that stock and they were happy to acknowledge their roots in northern Ireland and was a powerful lobby for a negotiated settlement in the home country which would play well in electoral politics of the US.

Greeting Nobel Prize winner John Hume

While their military units were kept out, political parties of both sides interacted with us often bringing maps and political literature while their gun toting “paras” guarded the perimeter of the hotel. We were not aware that discussions were going on behind the scenes with the Republic of Ireland pushing for an equitable solution for the Catholics. Indeed it was the recognition of the role of the Republic that paved the way for a settlement after Labour won a landslide victory under Tony Blair in 1987.

Finally an agreement called the “Good Friday Accord” were negotiated in 1988 with greater representation for the Catholics. This minutae of the negotiations were of much interest to us and meetings with Mc Guiness, Gerry Adams’ deputy, was a high point of our tour. Adams the IRA leader sent us autographed copies of his recently published biography “Fire in the Hills” as a memento. This book is now in my library. It reminds me of our memorable visit to Ireland at the height of the murderous conflict which was dominating global news at that time.

Several years later I was able to host John Hume the Irish leader who led the reconciliation process in Ireland and had won the Nobel prize for his effort. We had a meeting and dinner for him in Colombo with the cooperation of the British Embassy here.

Chittagong

International Alert arranged our next meeting in Bangladesh. The Chikma hill tribe of Chittagong were battling the Bangla army. The Chikmas holding the surrounding hills asked for autonomy as they were Buddhists with their own language and culture. Ethnically they were closer to the Kachin and Karen hill tribes who were confronting the Burmese and Thai military in their own countries. This time around our delegation was led by Bertie Dissanayake, a popular leader of the SLFP from Anuradhapura

district. Perhaps the organizers thought that a representative from our Buddhist heartland would be more acceptable to the rebels.

We first landed in Dhaka for consultations with the relevant Bangladeshi officials. They were all staunch Muslims who could not brook the thought of a conclave of Buddhists in their country ignoring the fact that Bangladesh had been founded because Pakistan had refused to recognize their individual language and culture. They too, like the Pakistanis, were set on a military solution to this ethnic crisis. I had done some research on Buddhism in the colonial period and knew that this area which was called Cox Bazaar by the British was part of old Arakan which was a Buddhist centre. In the colonial period Arakanese had been drawn to Calcutta which was the locus of a modern Buddhist revival, thanks to the Mahabodhi Society led by Anagarika Dharmapala.

We then left by bus to Chittagong. On the way we stopped at the site of the famous ancient Buddhist centre called Somapura Mahavihara. It was on a par with Nalanda, Vikramashila and Jaggadala Buddhist monasteries. Our request to visit the Chikma hills was turned down by the military. But we managed to go to a nearby town where some of the Chikma fighters met us. They unanimously sought our help to persuade the Bangladesh government to permit some devolution so that their distinctive identity would be preserved.

Their resources were so meagre that a settlement seemed to be the only way out. Happily, some time later an arrangement was made to accommodate them partly because Chittagong as a main port in the country grew rapidly as a garment hub. With greater economic benefits – including from several Sri Lankan managed garment factories – the Chikma problem was viewed more sympathetically and was eventually solved.

Manila

Our next rendezvous was Manila in the Philipines. The Mindanao rebellion was in full swing. The rebels were Muslims who were persecuted by the Manila authorities. The islands which saw an armed rebellion were closer to Indonesia and the Muslim militants there were funding and arming the rebels while the Philippines administration faced a logistical nightmare to get to the battle zone. We were precluded from visiting Mindanao on the grounds that it would be unsafe – a touching concern we observed in all the trouble spots in Northern Ireland, Bangladesh and now the Philippines.

However when the Filipino academics and security personnel briefed us in Manila it became clear that the solution lay outside their country. Accordingly there were long standing negotiations with Indonesia which were not going anywhere. Manila changed tack later and brought Saudi Arabia in as a mediator and achieved a good result. These discussions were very helpful for us MPs to understand the ramifications of ethnic conflicts and the need for foreign interlocutors. The JVP had earlier used this issue as a pretext to resume their violent activities which had ended in their military defeat and the killing of nearly all of their top leaders. There was a similar ending to the LTTE war.

There is one event which took place in Manila which still remains in my memory. Douglas Devananda and I took a stroll on a Manila street after a discussion session. We had hardly walked a mile when Douglas looked round and started running leaving me flabbergasted. I continued on my journey and came back to the hotel to find Douglas swimming in the hotel pool. When I asked him about his strange behaviour he told me that he had seen a LTTE gunman following us and that he had to run to escape a murder attempt.

To this day I do not know whether it was really so or that Douglas had imagined it. What I can say is that there were several attempts on his life later and that he has escaped them all even though many scars remain on his body to remind him that it was a close call.

Presidential Campaign 1994

The Presidential election was scheduled for November 1994. The two leading candidates were self selected in that both CBK and Gamini became the automatic choices of the two main contending parties. The latter however was under pressure, particularly from his family, to skip this election since at first CBK seemed invincible. However Gamini insisted on contesting and thereby putting his seal on the party, win or lose. We were also aware that there had been many internal disputes in the SLFP. I noticed that Gamini launched his campaign in a very professional manner bringing in Wickreme Weerasooria and Daham Wimalasena who had managed JRJ’s presidential bids.

He also seemed to be ready to outspend his rival whose antipathy to big business was well known. Another of his advantages was that he was indefatigable on the stump. With his financial backing he was using helicopters to crisscross the country and slowly the UNP party machine which had gone to sleep under Wijetunga and Ranil, began to wake up. Many observers opined that he was fast catching up on his rival.

That must have been the analysis of the LTTE as well because they would have only planned to assassinate him thinking that he had a chance of success. They calculated that if he won, Gamini would have India on his side. This was no fancy illusion because he was a firm favourite of the Gandhi family and the Indian Congress. When we celebrated his fiftieth birthday with a “Festschrift” entitled “50; A Beginning” India sent Natwar Singh, its State Minister of Foreign Affairs, to participate in the ceremony in Colombo. They were breaking protocol to honour a friend.

Thotalanga bomb blast

By late October 1994 the Presidential race was coming to its final lap. Both campaigns were in full swing and though CBK with her recent electoral victory appeared to be leading, Gamini was confident that he was catching up. He was pouring money into his campaign and redoubling his efforts to reach out to his supporters. He felt that he needed more time. He also was unhappy that Ranil was not throwing his weight behind the campaign. In fact we received intelligence that he was urging his close supporters to back CBK.

In his usual style Gamini confronted Ranil whom he had nurtured in the party in the early days and asked for his support. I too met Ranil at his house and urged him to support the party candidate. Gamini undertook helicopter rides to cover as much ground as possible in order to catch up on time lost in his battle to get back to the UNP. He overextended himself by trying to cover as many meetings as possible in a day, including late night meetings, which probably cost him his life.

I was with him on the morning of October 24, 1994. We went by helicopter for an early campaign in Kandy district. The first meeting was held in Kundasale presided over by Tissa Attanayake. Attanayake had been a cheerleader for Ranil and Gamini tried his best to win him over by flattering him in his speech. In my speech I introduced Gamini as a “native son” of Kandy, which pleased him. He told me that he planned to leave further campaigning in Kandy to me freeing him to stump in the marginal electorates.

We were joined by Dr. Palitha Randeniya, a Professor at Peradeniya University, who had become the virtual spokesman of a particular Kandyan caste. The three of us then took a short helicopter ride to Maratugoda in the Harispattuwa electorate for a meeting organised by ACS Hameed. The helicopter landed on the sports ground of Maratugoda senior school where a car had been arranged to take us to the venue of the meeting which was about two miles away. On the way we encountered a bad omen in that our car broke down half way and we had to waste time on the road till it was repaired.

To save time Gamini asked permission to speak early in his usual polite way. By this time GM Premachandra who represented the nearby Mawathagama electorate in Kurunegala district where the next meeting was to be held, was on the stage. I had told Gamini that I would not travel back with him by helicopter because my parents were living nearby in Nugawela and my father had wanted me to see him that day. I had a meeting with Eric Solheim arranged by my friend Arne Fjortoft at the Eighty Club that evening. I was in the midst of my speech when Gamini signaled that he was leaving. Since there was an empty seat in the helicopter due to my absence he had persuaded a reluctant Premachandra to join him.

Then a strange thing happened which has been lodged in my memory ever since. After reaching the end of the stage where the steps to the exit were located Gamini unexpectedly turned and walked back to me where I was busy speaking, tapped me on the arm and said that he was taking leave of me. The whole Harispattuwa audience saw that gesture of friendship. From the stage I caught a glimpse of him surrounded by his bodyguards heading towards his car amidst a knot of supporters who were cheering him. That was the last time I saw him alive.

He headed for the helicopter with Premachandra whom he had persuaded to join him on the rest of the tour as my sea twas available. They had returned to Colombo by evening to participate in the last meeting for the day at Thotalanga in the northern suburbs of the city. I had lunch with my parents and left for Colombo by car for my appointment with Eric Solheim. He had visited Myanmar to arrange for Norwegian aid and was interested in the Sri Lankan peace process.

After this visit he shifted his attention to Sri Lanka, and became a household name here. We had dinner and I went home to Siripa Road to sleep. Soon after midnight my bedside phone started ringing and I was shocked to receive the news of a bomb going off at Thotalanga. Many of the calls were to check whether I too had gone for Gamini’s meeting. At first I was told that my friend was alive and had been rushed to hospital. But soon the extent of damage became clear. Gamini was dead on arrival and so were many others including Premachandra and Wijesekere – the Secretary of the party.

My daughter Varuni and her husband Rohan were living in Siripa Road at that time and I persuaded them to quickly drive me to Gamini’s residence in Alfred House gardens. There was pandemonium there. Wickreme Weersooria asked me to go immediately to President’s House to brief Wijetunga. I had barely got there when CBK arrived in an agitated state. She was genuinely shocked and grieved by the assassination. We had a discussion and Wijetunga decided to give every possible state assistance for the funeral. CBK graciously agreed to all the measures that were proposed including a state funeral and a final ceremony in Independence square. I went back to Gamini’s house, sat in a corner in the veranda and could not hold back my tears. No one had expected our long journey to end in this terrible fashion.

After several days of “lying in state” when a large concourse of people filed past the bier the cremation was held in Independence square. The family wanted me to speak at the ceremony. Other speakers were several monks, Wijetunga, Ranil and a representative of the SLFP. N. Ram from Chennai flew down and joined me on the drive to Independence square. In my speech I invoked Gamini’s journey from Kotmale to the highest echelons of power. He was a model for every Sri Lankan young man. His achievements including the completion of the Mahaweli project, will remain in our memory.

It was a sad and emotional time for all of us and we went home exhausted to contemplate an uncertain future which had looked happily predictable only a week ago. I must place on record here that CBK acted with great sympathy during this period quite unlike the behaviour of Mrs. B and her Cabinet when they reacted shabbily to Dudley Senanayake’s death and funeral arrangements in the early seventies.

(Excerpted from vol. 3 of the Sarath Amunugama autbiography) ✍️

Features

Reconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

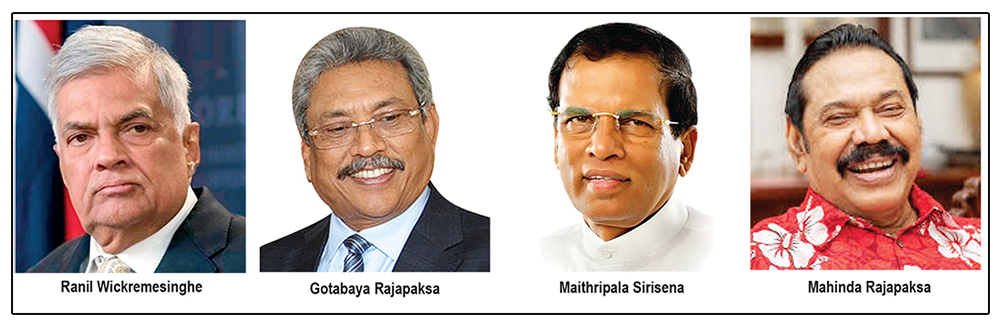

From the time the search for reconciliation began after the end of the war in 2009 and before the NPP’s victories at the presidential election and the parliamentary election in 2024, there have been four presidents and four governments who variously engaged with the task of reconciliation. From last to first, they were Ranil Wickremesinghe, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Maithripala Sirisena and Mahinda Rajapaksa. They had nothing in common between them except they were all different from President Anura Kumara Dissanayake and his approach to reconciliation.

The four former presidents approached the problem in the top-down direction, whereas AKD is championing the building-up approach – starting from the grassroots and spreading the message and the marches more laterally across communities. Mahinda Rajapaksa had his ‘agents’ among the Tamils and other minorities. Gotabaya Rajapaksa was the dummy agent for busybodies among the Sinhalese. Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe operated through the so called accredited representatives of the Tamils, the Muslims and the Malaiayaka (Indian) Tamils. But their operations did nothing for the strengthening of institutions at the provincial and the local levels. No did they bother about reaching out to the people.

As I recounted last week, the first and the only Northern Provincial Council election was held during the Mahinda Rajapaksa presidency. That nothing worthwhile came out of that Council was not mainly the fault of Mahinda Rajapaksa. His successors, Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe as Prime Minister, with the TNA acceding as a partner of their government, cancelled not only the NPC but also all PC elections and indefinitely suspended the functioning of the country’s nine elected provincial councils. Now there are no elected councils, only colonial-style governors and their secretaries.

Hold PC Elections Now

And the PC election can, like so many other inherited rotten cans, is before the NPP government. Is the NPP government going to play footsie with these elections or call them and be done with it? That is the question. Here are the cons and pros as I see them.

By delaying or postponing the PC elections President AKD and the NPP government are setting themselves up to be justifiably seen as following the cynical playbook of the former interim President Ranil Wickremesinghe. What is the point, it will be asked, in subjecting Ranil Wickremesinghe to police harassment over travel expenses while following his playbook in postponing elections?

Come to think of it, no VVIP anywhere can now whine of unfair police arrest after what happened to the disgraced former prince Andrew Mountbatten Windsor in England on Thursday. Good for the land where habeas corpus and due process were born. The King did not know what was happening to his kid brother, and he was wise enough to pronounce that “the law must take its course.” There is no course for the law in Trump’s America where Epstein spun his webs around rich and famous men and helpless teenage girls. Only cover up. Thanks to his Supreme Court, Trump can claim covering up to be a core function of his presidency, and therefore absolutely immune from prosecution. That is by the way.

Back to Sri Lanka, meddling with elections timing and process was the method of operations of previous governments. The NPP is supposed to change from the old ways and project a new way towards a Clean Sri Lanka built on social and ethical pillars. How does postponing elections square with the project of Clean Sri Lanka? That is the question that the government must be asking itself. The decision to hold PC elections should not be influenced by whether India is not asking for it or if Canada is requesting it.

Apart from it is the right thing do, it is also politically the smart thing to do.

The pros are aplenty for holding PC elections as soon it is practically possible for the Election Commission to hold them. Parliament can and must act to fill any legal loophole. The NPP’s political mojo is in the hustle and bustle of campaigning rather than in the sedentary business of governing. An election campaign will motivate the government to re-energize itself and reconnect with the people to regain momentum for the remainder of its term.

While it will not be possible to repeat the landslide miracle of the 2024 parliamentary election, the government can certainly hope and strive to either maintain or improve on its performance in the local government elections. The government is in a better position to test its chances now, before reaching the halfway mark of its first term in office than where it might be once past that mark.

The NPP can and must draw electoral confidence from the latest (February 2026) results of the Mood of the Nation poll conducted by Verité Research. The government should rate its chances higher than what any and all of the opposition parties would do with theirs. The Mood of the Nation is very positive not only for the NPP government but also about the way the people are thinking about the state of the country and its economy. The government’s approval rating is impressively high at 65% – up from 62% in February 2025 and way up from the lowly 24% that people thought of the Ranil-Rajapaksa government in July 2024. People’s mood is also encouragingly positive about the State of the Economy (57%, up from 35% and 28%); Economic Outlook (64%, up from 55% and 30%); the level of Satisfaction with the direction of the country( 59%, up from 46% and 17%).

These are positively encouraging numbers. Anyone familiar with North America will know that the general level of satisfaction has been abysmally low since the Iraq war and the great economic recession. The sour mood that invariably led to the election of Trump. Now the mood is sourer because of Trump and people in ever increasing numbers are looking for the light at the end of the Trump tunnel. As for Sri Lanka, the country has just come out of the 20-year long Rajapaksa-Ranil tunnel. The NPP represents the post Rajapaksa-Ranil era, and the people seem to be feeling damn good about it.

Of course, the pundits have pooh-poohed the opinion poll results. What else would you expect? You can imagine which twisted way the editorial keypads would have been pounded if the government’s approval rating had come under 50%, even 49.5%. There may have even been calls for the government to step down and get out. But the government has its approval rating at 65% – a level any government anywhere in the Trump-twisted world would be happy to exchange without tariffs. The political mood of the people is not unpalpable. Skeptical pundits and elites will have to only ask their drivers, gardeners and their retinue of domestics as to what they think of AKD, Sajith or Namal. Or they can ride a bus or take the train and check out the mood of fellow passengers. They will find Verité’s numbers are not at all far-fetched.

Confab Threats

The government’s plausible popularity and the opposition’s obvious weaknesses should be good enough reason for the government to have the PC elections sooner than later. A new election campaign will also provide the opportunity not only for the government but also for the opposition parties to push back on the looming threat of bad old communalism making a comeback. As reported last week, a “massive Sangha confab” is to be held at 2:00 PM on Friday, February 20th, at the All Ceylon Buddhist Congress Headquarters in Colombo, purportedly “to address alleged injustices among monks.”

According to a warning quote attributed to one of the organizers, Dambara Amila Thero, “never in the history of Sri Lanka has there been a government—elected by our own votes and the votes of the people—that has targeted and launched such systematic attacks against the entire Sasana as this one.” That is quite a mouthful and worthier practitioners of Buddhism have already criticized this unconvincing claim and its being the premise for a gathering of spuriously disaffected monks. It is not difficult to see the political impetus behind this confab.

The impetus obviously comes from washed up politicians who have tried every slogan from – L-board-economists, to constitutional dictatorship, to save-our children from sex-education fear mongering – to attack the NPP government and its credibility. They have not been able to stick any of that mud on the government. So, the old bandicoots are now trying to bring back the even older bogey of communalism on the pretext that the NPP government has somewhere, somehow, “targeted and launched such systematic attacks against the entire Sasana …”

By using a new election campaign to take on this threat, the government can turn the campaign into a positively educational outreach. That would be consistent with the President’s and the government’s commitment to “rebuild Sri Lanka” on the strength of national unity without allowing “division, racism, or extremism” to undermine unity. A potential election campaign that takes on the confab of extremists will also provide a forum and an opportunity for the opposition parties to let their positions known. There will of course be supporters of the confab monks, but hopefully they will be underwhelming and not overwhelming.

For all their shortcomings, Sajith Premadasa and Namal Rajapaksa belong to the same younger generation as Anura Kumara Dissanayake and they are unlikely to follow the footsteps of their fathers and fan the flames of communalism and extremism all over again. Campaigning against extremism need not and should not take the form of disparaging and deriding those who might be harbouring extremist views. Instead, the fight against extremism should be inclusive and not exclusive, should be positively educational and appeal to the broadest cross-section of people. That is the only sustainable way to fight extremism and weaken its impacts.

Provincial Councils and Reconciliation

In the framework of grand hopes and simple steps of reconciliation, provincial councils fall somewhere in between. They are part of the grand structure of the constitution but they are also usable instruments for achieving simple and practical goals. Obviously, the Northern Provincial Council assumes special significance in undertaking tasks associated with reconciliation. It is the only jurisdiction in the country where the Sri Lankan Tamils are able to mind their own business through their own representatives. All within an indivisibly united island country.

But people in the north will not be able to do anything unless there is a provincial council election and a newly elected council is established. If the NPP were to win a majority of seats in the next Northern Provincial Council that would be a historic achievement and a validation of its approach to national reconciliation. On the other hand, if the NPP fails to win a majority in the north, it will have the opportunity to demonstrate that it has the maturity to positively collaborate from the centre with a different provincial government in the north.

The Eastern Province is now home to all three ethnic groups and almost in equal proportions. Managing the Eastern Province will an experiential microcosm for managing the rest of the country. The NPP will have the opportunity to prove its mettle here – either as a governing party or as a responsible opposition party. The Central Province and the Badulla District in the Uva Province are where Malaiyaka Tamils have been able to reconstitute their citizenship credentials and exercise their voting rights with some meaningful consequence. For decades, the Malaiyaka Tamils were without voting rights. Now they can vote but there is no Council to vote for in the only province and district they predominantly leave. Is that fair?

In all the other six provinces, with the exception of the Greater Colombo Area in the Western Province and pockets of Muslim concentrations in the South, the Sinhalese predominate, and national politics is seamless with provincial politics. The overlap often leads to questions about the duplication in the PC system. Political duplication between national and provincial party organizations is real but can be avoided. But what is more important to avoid is the functional duplication between the central government in Colombo and the provincial councils. The NPP governments needs to develop a different a toolbox for dealing with the six provincial councils.

Indeed, each province regardless of the ethnic composition, has its own unique characteristics. They have long been ignored and smothered by the central bureaucracy. The provincial council system provides the framework for fostering the unique local characteristics and synthesizing them for national development. There is another dimension that could be of special relevance to the purpose of reconciliation.

And that is in the fostering of institutional partnerships and people to-people contacts between those in the North and East and those in the other Provinces. Linkages could be between schools, and between people in specific activities – such as farming, fishing and factory work. Such connections could be materialized through periodical visits, sharing of occupational challenges and experiences, and sports tournaments and ‘educational modules’ between schools. These interactions could become two-way secular pilgrimages supplementing the age old religious pilgrimages.

Historically, as Benedict Anderson discovered, secular pilgrimages have been an important part of nation building in many societies across the world. Read nation building as reconciliation in Sri Lanka. The NPP government with its grassroots prowess is well positioned to facilitate impactful secular pilgrimages. But for all that, there must be provincial councils elections first.

by Rajan Philips

Features

Barking up the wrong tree

The idiom “Barking up the wrong tree” means pursuing a mistaken line of thought, accusing the wrong person, or looking for solutions in the wrong place. It refers to hounds barking at a tree that their prey has already escaped from. This aptly describes the current misplaced blame for young people’s declining interest in religion, especially Buddhism.

It is a global phenomenon that young people are increasingly disengaged from organized religion, but this shift does not equate to total abandonment, many Gen Z and Millennials opt for individual, non-institutional spirituality over traditional structures. However, the circumstances surrounding Buddhism in Sri Lanka is an oddity compared to what goes on with religions in other countries. For example, the interest in Buddha Dhamma in the Western countries is growing, especially among the educated young. The outpouring of emotions along the 3,700 Km Peace March done by 16 Buddhist monks in USA is only one example.

There are good reasons for Gen Z and Millennials in Sri Lanka to be disinterested in Buddhism, but it is not an easy task for Baby Boomer or Baby Bust generations, those born before 1980, to grasp these bitter truths that cast doubt on tradition. The two most important reasons are: a) Sri Lankan Buddhism has drifted away from what the Buddha taught, and b) The Gen Z and Millennials tend to be more informed and better rational thinkers compared to older generations.

This is truly a tragic situation: what the Buddha taught is an advanced view of reality that is supremely suited for rational analyses, but historical circumstances have deprived the younger generations over centuries from knowing that truth. Those who are concerned about the future of Buddhism must endeavor to understand how we got here and take measures to bridge that information gap instead of trying to find fault with others. Both laity and clergy are victims of historical circumstances; but they have the power to shape the future.

First, it pays to understand how what the Buddha taught, or Dhamma, transformed into 13 plus schools of Buddhism found today. Based on eternal truths he discovered, the Buddha initiated a profound ethical and intellectual movement that fundamentally challenged the established religious, intellectual, and social structures of sixth-century BCE India. His movement represented a shift away from ritualistic, dogmatic, and hierarchical systems (Brahmanism) toward an empirical, self-reliant path focused on ethics, compassion, and liberation from suffering. When Buddhism spread to other countries, it transformed into different forms by absorbing and adopting the beliefs, rituals, and customs indigenous to such land; Buddha did not teach different truths, he taught one truth.

Sri Lankan Buddhism is not any different. There was resistance to the Buddha’s movement from Brahmins during his lifetime, but it intensified after his passing, which was responsible in part for the disappearance of Buddhism from its birthplace. Brahminism existed in Sri Lanka before the arrival of Buddhism, and the transformation of Buddhism under Brahminic influences is undeniable and it continues to date.

This transformation was additionally enabled by the significant challenges encountered by Buddhism during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Wachissara 1961, Mirando 1985). It is sad and difficult to accept, but Buddhism nearly disappeared from the land that committed the Teaching into writing for the first time. During these tough times, with no senior monks to perform ‘upasampada,’ quasi monks who had not been admitted to the order – Ganninanses, maintained the temples. Lacking any understanding of the doctrinal aspects of Buddha’s teaching, they started performing various rituals that Buddha himself rejected (Rahula 1956, Marasinghe 1974, Gombrich 1988, 1997, Obeyesekere 2018).

The agrarian population had no way of knowing or understanding the teachings of the Buddha to realize the difference. They wanted an easy path to salvation, some power to help overcome an illness, protect crops from pests or elements; as a result, the rituals including praying and giving offerings to various deities and spirits, a Brahminic practice that Buddha rejected in no uncertain terms, became established as part of Buddhism.

This incorporation of Brahminic practices was further strengthened by the ascent of Nayakkar princes to the throne of Kandy (1739–1815) who came from the Madurai Nayak dynasty in South India. Even though they converted to Buddhism, they did not have any understanding of the Teaching; they were educated and groomed by Brahminic gurus who opposed Buddhism. However, they had no trouble promoting the beliefs and rituals that were of Brahminic origin and supporting the institution that performed them. By the time British took over, nobody had any doubts that the beliefs, myths, and rituals of the Sinhala people were genuine aspects of Buddha’s teaching. The result is that today, Sri Lankan Buddhists dare doubt the status quo.

The inclusion of Buddhist literary work as historical facts in public education during the late nineteenth century Buddhist revival did not help either. Officially compelling generations of students to believe poetic embellishments as facts gave the impression that Buddhism is a ritualistic practice based on beliefs.

This did not create any conflict in the minds of 19th agrarian society; to them, having any doubts about the tradition was an unthinkable, unforgiving act. However, modernization of society, increased access to information, and promotion of rational thinking changed things. Younger generations have begun to see the futility of current practices and distance themselves from the traditional institution. In fact, they may have never heard of it, but they are following Buddha’s advice to Kalamas, instinctively. They cannot be blamed, instead, their rational thinking must be appreciated and promoted. It is the way the Buddha’s teaching, the eternal truth, is taught and practiced that needs adjustment.

The truths that Buddha discovered are eternal, but they have been interpreted in different ways over two and a half millennia to suit the prevailing status of the society. In this age, when science is considered the standard, the truth must be viewed from that angle. There is nothing wrong or to be afraid of about it for what the Buddha taught is not only highly scientific, but it is also ahead of science in dealing with human mind. It is time to think out of the box, instead of regurgitating exegesis meant for a bygone era.

For example, the Buddhist model of human cognition presented in the formula of Five Aggregates (pancakkhanda) provides solutions to the puzzles that modern neuroscience and philosophers are grappling with. It must be recognized that this formula deals with the way in which human mind gathers and analyzes information, which is the foundation of AI revolution. If the Gen Z and Millennial were introduced to these empirical aspects of Dhamma, they would develop a genuine interest in it. They thrive in that environment. Furthermore, knowing Buddha’s teaching this way has other benefits; they would find solutions to many problems they face today.

Buddha’s teaching is a way to understand nature and the humans place in it. One who understands this can lead a happy and prosperous life. As the Dhammapada verse number 160 states – “One, indeed, is one’s own refuge. Who else could be one’s own refuge?” – such a person does not depend on praying or offering to idols or unknown higher powers for salvation, the Brahminic practice. Therefore, it is time that all involved, clergy and laity, look inwards, and have the crucial discussion on how to educate the next generation if they wish to avoid Sri Lankan Buddhism suffer the same fate it did in India.

by Geewananda Gunawardana, Ph.D.

Features

Why does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

The Feminist Collective for Economic Justice (FCEJ) is outraged at the scheme of law proposed by the government titled “Protection of the State from Terrorism Act” (PSTA). The draft law seeks to replace the existing repressive provisions of the Prevention of Terrorism Act 1979 (PTA) with another law of extraordinary powers. We oppose the PSTA for the reason that we stand against repressive laws, normalization of extraordinary executive power and continued militarization. Ruling by fear destroys our societies. It drives inequality, marginalization and corruption.

Our analysis of the draft PSTA is that it is worse than the PTA. It fails to justify why it is necessary in today’s context. The PSTA continues the broad and vague definition of acts of terrorism. It also dangerously expands as threatening activities of ‘encouragement’, ‘publication’ and ‘training’. The draft law proposes broad powers of arrest for the police, introduces powers of arrest to the armed forces and coast guards, and continues to recognize administrative detention. Extremely disappointing is the unjustifiable empowering of the President to make curfew order and to proscribe organizations for indefinite periods of time, the power of the Secretary to the Ministry of Defence to declare prohibited places and police officers in the rank of Deputy Inspector Generals are given the power to secure restriction orders affecting movement of citizens. The draft also introduces, knowing full well the context of laws delays, the legal perversion of empowering the Attorney General to suspend prosecution for 20 years on the condition that a suspect agrees to a form of punishment such as public apology, payment of compensation, community service, and rehabilitation. Sri Lanka does not need a law normalizing extraordinary power.

We take this moment to remind our country of the devastation caused to minoritized populations under laws such as the PTA and the continued militarization, surveillance and oppression aided by rapidly growing security legislation. There is very limited space for recovery and reconciliation post war and also barely space for low income working people to aspire to physical, emotional and financial security. The threat posed by even proposing such an oppressive law as the PSTA is an affront to feminist conceptions of human security. Security must be recognized at an individual and community level to have any meaning.

The urgent human security needs in Sri Lanka are undeniable – over 50% of households in the country are in debt, a quarter of the population are living in poverty, over 30% of households experience moderate/severe food insecurity issues, the police receive over 100,000 complaints of domestic violence each year. We are experiencing deepening inequality, growing poverty, assaults on the education and health systems of the country, tightening of the noose of austerity, the continued failure to breathe confidence and trust towards reconciliation, recovery, restitution post war, and a failure to recognize and respond to structural discrimination based on gender, race and class, religion. State security cannot be conceived or discussed without people first being safe, secure, and can hope for paths towards developing their lives without threat, violence and discrimination. One year into power and there has been no significant legislative or policy moves on addressing austerity, rolling back of repressive laws, addressing domestic and other forms of violence against women, violence associated with household debt, equality in the family, equality of representation at all levels, and the continued discrimination of the Malaiyah people.

The draft PSTA tells us that no lessons have been learnt. It tells us that this government intends to continue state tools of repression and maintain militarization. It is hard to lose hope within just a year of a new government coming into power with a significant mandate from the people to change the system, and yet we are here. For women, young people, children and working class citizens in this country everyday is a struggle, everyday is a minefield of threats and discrimination. We do not need another threat in the form of the PSTA. Withdraw the PSTA now!

The Feminist Collective for Economic Justice is a collective of feminist economists, scholars, feminist activists, university students and lawyers that came together in April 2022 to understand, analyze and give voice to policy recommendations based on lived realities in the current economic crisis in Sri Lanka.

Please send your comments to – feministcollectiveforjustice@gmail.com

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoGiants in our backyard: Why Sri Lanka’s Blue Whales matter to the world

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoOld and new at the SSC, just like Pakistan

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoConstruction begins on country’s largest solar power project in Hambantota

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoIMF MD here