Features

JRJ begins to lose control, gets me back to Colombo and some inside stories of the day

(Excerpted from volume ii of the Sarath Amunugama autobiography)

This was about the nadir of JRJ’s administration. He was beginning to lose control. On one side the JVP which was sent underground by his fiat, realized that the parliamentary road was not immediately open to them. Wijeweera is reputed to have said that it would take the JVP 50 years to win a popular election. Unlike in 1971 they succeeded in unleashing a reign of terror after the signing of the Indo-Lanka accord which paralyzed the country.

JRJ could not fight on two fronts – the north and south – which Premadasa compared to a fire at both ends of a `flambeau’ [Vilakku] used in Sinhala healing rituals. The northern situation was reaching a stalemate since India was exerting strong diplomatic pressure which crippled the efforts of the armed forces. When the army under Lalith Athulathmudali had the LTTE encircled in Vadamaradchi, they were forced to call off the assault by the President.

The LTTE was armed and trained by Indian irregulars. The West that JRJ turned to had comforting words but was not willing to take India to task. The socialist block saw no reason to come to the aid of a leader who claimed to ‘roll back socialism’. It was in those bleak circumstances for JRJ that Indira Gandhi was killed by her Sikh bodyguard, which led to another twist in the fate of the Sri Lankan government.

In Paris we were glued to our TV sets as pictures from the funeral ceremony of Indira in Delhi were beamed on ‘real time’ to our drawing rooms. The nation was in shock and the vast concourse that assembled in ‘Shand Vana’ saw Rajiv Gandhi not only taking the leading role in the ceremony but being positioned by the power brokers of the Congress to succeed his mother, even though he was initially uncertain.

But if the power brokers thought they could continue with business as usual, they were mistaken. After a short while a new generation of tech savvy advisors came to the fore. Businessmen like Tatas, of Parsee origins like the new Prime Minister, replaced the Gujeratis like the Ambanis and a new pro-West shift replaced Indira’s ingrained hostility to the West, which was also a contributory factor for her jaundiced view of JRJ and his government.

In Tamil Nadu affairs Parathasarathy as advisor was replaced by Romesh Bandari. I felt this immediately in Paris as GP lost his clout and was replaced as head of the Indian delegation by Foreign Service officers like Dixit and Kaul. Gamini Dissanayake, who was backed strongly by the Maharaja Group, now entered the scene in a big way because as the head of the Board of Control of Cricket he could interact freely with the Indian elite who were cricket fanatics.

At that time we were knocking on the door to be recognized for test cricket and Gamini with his charm and ample financial backing, was determined to gain entry. The key to unlocking this conundrum was Indian support and that was obtained by Gamini with his customary flair. A favourable factor, which can be now disclosed, was Gamini’s links with the Balfour Beatty company, a British giant which was the contractor for the Victoria Reservoir project. This company threw its weight behind our application.

The Head of the company in the UK was the chief fund raiser for Thatcher’s Conservative Party. Gamini used the clout of Balfour — Beatty to twist the arm of the MCC. I once went with Gamini and High Commissioner Monerawela to view an early match between England and Sri Lanka at Lords. We were welcomed to the distinguished visitors’ gallery and served champagne and wafer thin smoked salmon as well as cucumber sandwiches ordered from Fortnum and Mason. By that time Sri Lanka was in the select group with test status and in that match Wettimuny, if my memory serves, scored a century.

Another of Gamin’s `coup’s was to get Sir Garfield Sobers as a coach. He was at the height of his fame and his involvement was a great inspiration for our boys. Arjuna Ranatunga who is a fearless leader, brought the World cup won by our team straight from the airport to Gamini’s house and presented it to Srima in gratitude for her husband’s superb contribution, even though Gamini was dead by then and his rival Chandrika was President. It stands to Chandrika’s credit that she took this act of grace with dignity.

Cricket brought Gamini into contact with Ram of the Hindu newspaper group and they became firm friends. I can attest to this since I too was brought into the circle of Ram’s friends. When Gamini was killed, Ram flew down from Chennai for the funeral and I took him in my car to the cremation ground. An aside I can reveal that Ram gifted high class Labrador to both Gamini and Chandrika. Though they were rivals the Presidency their favourite dogs came from the same source.

Chandrika’s dog was well known when she was President pet would follow her everywhere and was a signal that CBK was near. Chandrika was congenitally late and we would anxiously await the entry of the dog, particularly at Cabinet meetings, we could prepare ourselves for the discussion as soon as the four-footed herald ambled in and curled itself under the President’s chair. It was the custom for us to get up when the President entered the room. However, one lady minister known for sycophancy would shoot up as soon as she saw the dog much to our amusement. When Chandrika left office this minister was the first to abandon her heroine and literally fall at the feet of Mahinda Rajapakse.

Unexpected deaths

By the end of 1985 our group of friends in Paris had to two shocks. They were the unexpected deaths of Sarath Muttetuwegama and Esmond Wickremesinghe. Both were close to me and had stayed with us in Paris and the news their deaths was extremely disturbing. Sarath M. who was longtime friend and relative, had lived with his family on Siripa road just a few houses away from ours. His children – Ramani and Maitri – and ours were the closest of friends and were in and am of our respective homes.

On our invitation the Muttetuwegama children spent their long vacation with us visiting the tourist sites in France. They flew to Paris via Moscow by Aeroflot and their-return journey to Colombo, again through Moscow, led is a hilarious misunderstanding by the USSR officials. In typical bureaucratic style information had been conveyed by the Russian embassy in Colombo that Mr. and Mrs. Muttetuwegama were in transit. Officials had prepared a warm welcome to the rising star of the Ceylon Communist Party and his wife.

Imagine their surprise when two kids came down the gangway answering to the name of Muttetuwegama. To make matters worse young Maithri Muttetuwegama was waving the cowboy hat I had bought for him in Paris. I was told that the officials, loath to admit their error, had wined and dined the two children not forgetting to propose several toasts with good wishes for Sri Lanka-USSR friendship. Not long after, Sarath was killed in a road accident in Ratnapura and we lost a brilliant and incorruptible politician. His role as a brave Opposition Parliamentarian in the era of JRJ, as the lone Marxist voice, has entered the stuff of legend and is a lesson to all young politicians of today.

Esmond’s death was equally shocking. We had looked forward to his regular visits to Paris and the inside information about Sri Lankan politics that he freely provided. He was always conscious of his family’s proclivity to heart disease. His father and two younger brothers, Tissa and Lakshman, had died at a comparatively young age. In typical style he had studied the literature on heart disease, consulted his physician Dr. Thenuwara and selected Dr. de Bakey of Houston, who was the world’s best known heart surgeon, to perform a surgical procedure on him. On his way to Texas, he stayed with us in Rue Jean Daudin and a few of us took him to the airport for his flight to the US. He was in the best of spirits, and we knew that he was very keen to regain his vitality and get back to Colombo to resume his backroom involvement as JRJ’s chief political advisor and hatchet man.

Unfortunately, everything started going wrong in the US. De Bakey was planning to leave on a holiday and was ready to operate immediately without regard to an old man’s-tired condition after coming halfway across the world. By the time Esmond began to come to after his operation De Bakey had left on his holiday. When his kidneys began to fail there were no kidney specialists on call. Dr. Thenuwara was at his wits end but there was nothing he could do. Esmond held on for a few days.

Ranil managed to reach his father’s bedside after a marathon flight but Esmond breathed his last not long after. We were saddened by this misadventure, which in our estimation, could have been avoided had he sought treatment in an Asian hospital. Manu, Premachandra and I and several of the embassy minor staff organized a ‘dane’ in his memory at the Paris Vihara and I conveyed our condolences to Ranil when I met him at his home sometime later.

While these deaths cast a pall of sorrow on our group in Paris, the news from Sri Lanka was equally bad. The ethnic conflict had now transformed itself into a shooting war. Whenever I met my friends Gamini Dissanayake, and Wickreme Weerasooria I was told that in addition to the military debacles we were also losing the media war. As the Biafra and Belfast insurrections showed, the media could be manipulated by rebels to portray state forces as merciless killers – particularly child killers – and occupy moral high ground in the face of international opinion. In fact the Biafran war drew attention to the role of western advertising agencies who launched expensive global media campaigns to gain political support and funds for their rebel clients.

Today it is axiomatic that anti-state fighters need to use propaganda as much as guns in their battles, The LTTE with its tentacles in the Tamil diaspora and assiduous wooing of western journalists was winning the propaganda war. The Government information apparatus and the Foreign Service were no match for the fanatical LTTE propagandists, many of them having personal knowledge of the terror of July 1983.

Anandatissa de Alwis the Minister of Information, was ill and beset with family problems. He was also demoralized by what he perceived as JRJ’s unwillingness to recreate what had earlier been a ‘special relationship’ between the two of them.

Time had passed and new aspirants to leadership like Gamini and Lalith had overtaken him. In the Ministry, my batchmate in the CCS, Buddhin Gunatunga, who was my dear friend, was the Permanent Secretary. He was a laid-back bureaucrat who was not particularly interested in media affairs.

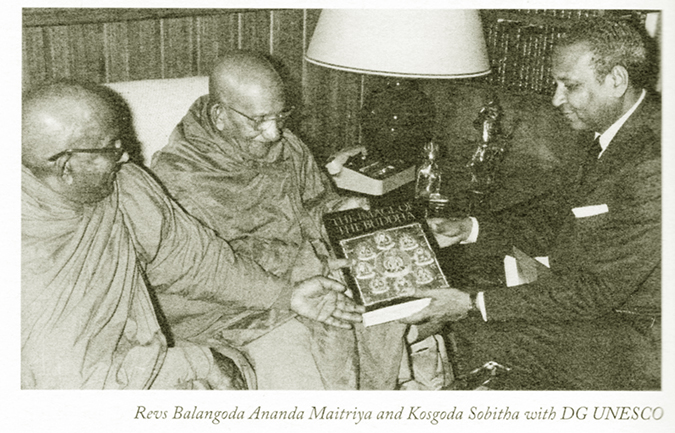

The Ministry had yet to play a positive role in the ethnic crisis. Buddhin may not have been in the best of health either as he was to die a few years later. In this background the President wanted me to come back and help him in the field of information at this crucial juncture. He wrote the following letter to M’Bow the DG of UNESCO and my employer in Paris on April 22, 1986.

“I am writing this letter to you to seek your assistance in a matter of considerable importance to Sri Lanka. As you may perhaps be aware, we have had to face many difficulties in the last few years due to terrorist activities in certain parts of the country.

My government has tried its utmost to find ways of settling this issue through negotiation with the different groups involved. It is clear to me that in order to assist this process of negotiation and conciliation it is necessary to inform the public both of my country and abroad of the issues involved and to create an environment conducive to a peaceful settlement. For this purpose, I intend to reorganize the information services of Sri Lanka in the near future.

“I will be greatly assisted in this task if I could obtain the services of Mr. Sarath Amunugama, Director of the International Programme for the Development of Communication of UNESCO, for a period of six months beginning June 1986. Prior to his joining UNESCO Mr. Amunugama was the Secretary to the Ministry of State which is responsible for Information and Broadcasting. He has established good working relations with the local and foreign media which can play a very important role in the present context of Sri Lanka. I sincerely hope it would be possible for you to release Mr. Amunugama for the period requested by me”.

M’Bow had extended my tenure for another four years in a letter dated August 11, 1986, which thanked me for my services and looked forward to a continuing association. I had only to respond positively to carry on in Paris with an enhanced salary. My two children were well settled in University and the overseas British school respectively. My wife was keen to continue in Paris where the family would be together and enjoy all the creature comforts.

On the other hand if I continued in Paris I would have ended up as a permanent resident in a foreign land. All my friends who remained behind were reconciled to their children marrying locals and settling down to a life in France. As parents they did not come back home after retirement or came back much later in time in their lives when they were ill or infirm. I was averse to the idea of coming back only to die in my motherland as some of my colleagues had done.

M’Bow helped me defer taking a decision when he responding to JRJ’s letter gave me a month’s paid leave to get back to Sri Lanka. This was a great gesture since the preparatory work for the annual General Meeting of IPDC had begun and my input was necessary at that juncture. I thought that a month-long visit to Sri Lanka would help me to clarify my situation and chart my future course of action. I made ready to leave for Colombo.

Rajiv and Romesh Bhandari

The death of Indira Gandhi and the succession of her son Rajiv as PM of India brought about a sea change in India’s approach towards the Sikhs as well as the Tamils in Sri Lanka. Most of the Tamilian officials principally Parathsarathy and Venketeshwaran were moved out and his personal loyalists like Romesh Bhandari, Chidambaram and Ram became his advisors on the Sri Lanka issue. Having won the Parliamentary election following Indira’s death, with an unprecedented majority, Rajiv had the freedom to change policies as well as infuse a sense of urgency in foreign -Affairs.

He was not dependent on the Tamil vote in the Lok Sabha. His tilt towards an open economy and closer relations with the west, a departure from his mother’s outdated socialism, summarized in her slogan ‘Garibi Hatao’ [Abolish Poverty], which proved to be a failure, made him a favourite of western governments and the media. I was in Paris when he made a successful state visit to France. Its high point was the pouring of Ganges water Rajiv had brought with him, into the Seine highlighting the confluence of their cultures and aspirations.

But what most impressed the Europeans was the shifting of arms procurement from the Russian arsenal to French, Italian and Swedish products. Thus French attack airplanes like the Dassault and long range guns from Bofors of Sweden entered the weaponry of the burgeoning Indian armed forces. This led to much criticism from the left leaning politicians and media practitioners who were constantly harping on the Italian birth nationality of Sonia, the PM’s assertive wife. They launched an attack on Rajiv’s purchase of modern long range guns from Bofors but could not deflect him from following modern economic policies.

This shift helped Rajiv to get western support for his initiatives in both Punjab and Sri Lanka. After the bloodbath of Sikhs living outside the Punjab following Indira’s assassination, a compromise was worked out and the Khalistan issue was laid to rest, at least for a long time. Rajiv then turned to the Sri Lanka issue with the same philosophy of cooperation, maximum devolution and a good neighbour policy. This approach held much promise and all in India and Sri Lanka were enthusiastic about giving it a chance.

His point man in this effort was Romesh Bhandari, a senior Foreign Service officer who was an amiable person unlike the dour Tamils who were Indira’s advisors. Accordingly, both Rajiv and his Foreign Secretary struck up a cordial relationship with JRJ. Rajiv called JRJ ‘uncle’ and I was aware that our wily leader reminisced about his friendship with the PM’s grandfather Nehru and his experiences with the Congress leaders of his youth when he participated in the Ramgarh Congress meeting prior to independence.

JRJ referred to his correspondence with Nehru is the pre-Independence period. At my urging he wrote an article about his links with the Congress leaders of that time. He wanted it published in India. I contacted my friend Dilip Padgoankar who was an advisor to the Jain family, the owners of the Times of India group of newspapers. Later Dilip became the Editor of the Times of India. We decided that the article should be published in the Illustrated Weekly of India which also was owned by the Jain group.

The article was published by the magazines editor Rafik Zakaria. This magazine was very popular among top elite and we were able to position JRJ as ‘a lover of India’ in the context of much anti Sri Lanka feeling generated during the time of Indira Gandhi. The fly in the ointment was Zakaria’s unhelpful headline which read “An Old Fox Remembers”.

I spent quite some time in brushing up JRJ’s image prior to the SAARC meeting to be held in Bangalore in November 1986. At this meeting the two leaders were to discuss the ethnic issue on the sidelines of the meeting which according to its mandate did not formally discuss bilateral matters. In consultation with JRJ, I decided that we should make a special media effort to woo Rajiv. I also, in discussion with my friend Gamini Dissanayake on whom JRJ was depending more on and more to handle the ethnic issue, decided to come back to my home country and assist him and JRJ in a more sustained manner. Accordingly, I terminated my employment with UNESCO with the following letter to M’Bow:

“I thank you for your letter in which you kindly inform me of your decision to extend the engagement of my services to UNESCO. I would have been very happy to accept but the President of Sri Lanka has requested me to return so that he could make use of my services in a very crucial area of his Government. In these circumstances I have decided, reluctantly, that I will not seek an extension of my contract. May I thank you most sincerely for the courtesy, understanding and friendship you have extended to me during my tenure of office. I look forward to working closely with you in the future.”

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

Features

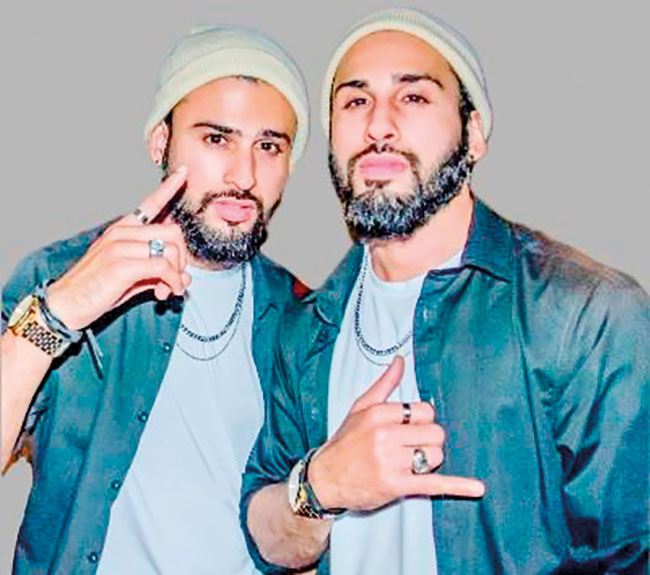

Special milestone for JJ Twins

The JJ Twins, the Sri Lankan musical duo, performing in the Maldives, and known for blending R&B, Hip Hop, and Sri Lankan rhythms, thereby creating a unique sound, have come out with a brand-new single ‘Me Mawathe.’

In fact, it’s a very special milestone for the twin brothers, Julian and Jason Prins, as ‘Me Mawathe’ is their first ever Sinhala song!

‘Me Mawathe’ showcases a fresh new sound, while staying true to the signature harmony and emotion that their fans love.

This heartfelt track captures the beauty of love, journey, and connection, brought to life through powerful vocals and captivating melodies.

It marks an exciting new chapter for the JJ Twins as they expand their musical journey and connect with audiences in a whole new way.

Their recent album, ‘CONCLUDED,’ explores themes of love, heartbreak, and healing, and include hits like ‘Can’t Get You Off My Mind’ and ‘You Left Me Here to Die’ which showcase their emotional intensity.

Readers could stay connected and follow JJ Twins on social media for exclusive updates, behind-the-scenes moments, and upcoming releases:

Instagram: http://instagram.com/jjtwinsofficial

TikTok: http://tiktok.com/@jjtwinsmusic

Facebook: http://facebook.com/jjtwinssingers

YouTube: http://youtube.com/jjtwins

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoFuture must be won

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans