Features

Joining in Psychosocial work back home in Sri Lanka

(Excerpted from Memories that linger…..My journey in the world of disability by Padmani Mendis)

When my memories come back to Sri Lanka they call out urgently, “Remember first the Psychosocial Project!” For the PSP was unique. It was implemented during the long conflict for our people affected by it in the northern and eastern parts of our country. Led by Gameela Samarasinghe and Ananda Galapatti with Harini Amarasuriya, Kusala Wettasinghe and others.

Later, but still also during the conflict, with some of these and other committed psychosocial workers memories of meeting needs this time of our “Ranaviru” or disabled soldiers. This was with the Ranaviru Seva Authority, RVSA, under the chairmanship of Dr. Narme Wickramasinghe with the able assistance of Dr. Visakha Dissanayake. The RVSA worked in the areas where our armed forces came from.

Within both the PSP and the RVSA I had the privilege of being invited to work with our psychosocial workers to see to the disability needs of civilians in the first project and of members of our armed forces in the second with whom they interacted. Those were difficult times for our people, but as always, our young professionals stepped forward to serve their fellow country women and men.

Introducing Community-based Rehabilitation to the NGO Sector in Sri Lanka

To continue with memories of my journey, I have to go back now to the year 1979 and the month of August, when I returned home after my first assignment for the WHO in Geneva. Whilst I was carrying out my task participating with so many others in the global development of the concept, strategy and technology of CBR (Community Based Rehabilitation), my thoughts were constantly of how these would fit so well in Sri Lanka to benefit our disabled people.

So, no sooner I returned to Colombo, I made an appointment to meet the Deputy Leader of the NGO Sarvodaya, which in Sri Lanka has been the most well-known NGO in community development. The work of Sarvodaya was based on social mobilisation, just as CBR is. I had come to know Mrs. Sita Rajasooriya when she was a Commissioner in the Girl Guide Movement and I was a teenage girl guide.

Over a chat about what I had been doing in Geneva, I gave her a copy of the WHO Manual and asked her whether she would look at it. She called me a year or so later to tell me that Sarvodaya was implementing a CBR Project in the district of Kalutara in the Western province. I have been there and elsewhere with Sarvodaya several times, visiting with them their people in their homes.

Over the next several years, other NGOs called on me to help them start implementing CBR in many parts of Sri Lanka – Fridsro in Kandy in the Central province, Navajeevana in Tangalle in the Southern province and SEED (Social, Economic and Educational Developers) in Vavuniya in the Northern province were some of the larger ones. All the projects had funding partnerships with outside donors. With evidence of visible and measurable impact, projects grew. In the long-term however potential growth was sometimes stunted by limited funding.

I shall come back to Fridsro later and its relationship with Government CBR programmes under the leadership of Gihan Galekotuwa. Fridsro sans Gihan Galekotuwa has now had to fade out of the realm of disability due to unavailability of sponsorship.

Sarvodaya, Navajeevana and SEED led respectively by Dr. A.T. Ariyaratne, and later his son Vinya, the late Kumarini Wikramasuriya and Ponnambalam Narasingham, together with many other NGOs continue their work in disability promoting CBR. The last of the three named above gave his formal name reluctantly when I asked him just now on the telephone, emphasising that he preferred being called “Singham”. This is what I had always known him by.

Time spent with these organisations so long ago are among my most memorable. With SEED it was focused on teaching their staff. SEED had been within sight of the conflict. We used for teaching the top floor of their three-storey building with a roof made of green metal sheets. Made the room very, very warm. But the breeze that wafted through its open sides compensated somewhat.

Here we had some of the most participatory of my teaching sessions in Sri Lanka. SEED staff were active, interested, motivated. Both the heat generated in the atmosphere and that in debate called for frequent ice breakers. These were innovative and enjoyable. But mostly I sat out, needing for myself a mental and physical break from all that dynamism around me.

The only hotel in Vavuniya was filled to capacity with families from the North fleeing the conflict. I stayed there only once. Having to jump over a smelly open sewer made so by disrepair to get into the hotel was off-putting. The disrepair extended to the inside of the hotel because such was the time. Compensating for this the management was concerned and kind, and had found for me a small room with many stairs to climb to get to it. I had all my meals here in my room because there was no other place for it. It was simply furnished with a bed, desk and chair.

There was no kitchen either and the hotel bought me my food from outside. An upset tummy on a few occasions indicated to me that I should find other lodgings next time. So on my following visits, SEED found for me a convent to stay at. Here, living with nuns, I felt cherished. I was their first paying guest. They were truly beautiful with their warmth and their empathy.

Other Experiences with NGOs

Many years later, and still during the long conflict, I was back North again twice on my journey. The first time I was in Jaffna. It was with Save the Children Fund (SCF), UK. They sent me so I could advise them how they could include actions for disabled children within their Northern programme.

Much of Jaffna district at the time was under the control of the Tamil Tigers. SCF had to obtain special permission for me to come to Jaffna, which, it turned out, they did quite easily. I believe it was easy because someone had got my name wrong. On the letter granting permission it was written “Pathmini”, the way it is in Tamil. I was given permission to travel anywhere I needed. I was not even stopped at checkpoints. Everywhere I went, it seemed as though I was expected.

The next work assignment in the North at this time included coming back to Vavuniya. I was here with Hameed of UNICEF as part of a series of teaching assignments I did to introduce to district and divisional officials issues related to disability in children. And to discuss with them how they may deal with such issues during the course of their work, so attempting to include childhood disability in development strategies during this time of conflict.

The series also covered Puttalam, Mannar and Trincomalee, stretching out across our island. As far as I know, those workshops were never followed up. I hope the seed had been planted in many an interested mind and would have taken root in some. It was a difficult time for all.

Before my memories of the NGO sector move on, there is another that asks for recall. Save the Children Fund, UK showed much concern for disabled children, making their work inclusive to the extent possible. With that in mind, they had me develop for them in partnership with teachers, parents, children and others, “A Guide for Preschool Teachers”. SCF had it published in all three languages and it was widely used, especially in CBR. It helped bring into the preschool mainstream many young children at an early age. This was a task that gave me much satisfaction.

This was soon after the Tsunami of 2006. Looking back, it is clear that activities of the International NGOs at this time was at a peak. Sri Lanka was the beneficiary of generous help from a caring world.

How CBR came to be in government

Dudley Dissanayake was the Director of the School of Social Work managed by the Department of Social Services. This was located on Bagatalle Road in a two-storied house. Rent was paid for by Government. One day I received a call from Dudley asking if we could meet. We met the next day. He told me about the reason for his call.

He said that quite recently he had found in the back seat of the pick-up truck that he drove, a photocopy of a book. He did not know how it had got there, but his staff shared the use of the pick-up truck. They used this also to transport students for official tasks.

The book had been made by WHO and was about disabled people. It had my name on the cover along with two others. Dudley wanted to know what it was about. I was of course only too happy to share with him the work I was doing in Geneva with my colleagues Gunnel Nelson and Einar Helander and with innumerable others spread throughout many countries.

This was now 1981 which the UN had declared as the “International Year of the Disabled”. It was customary for the UN to do such things on subjects that they felt required the attention of member states. To mark its significance, Dudley felt that students of social work should have an exposure with disabled people and disability. We discussed how this could be done.

The result was that two students expressed their wish to carry out their final year project study testing the usefulness of the Manual in Sri Lanka. Dudley asked me if I could help them, and I believe I was fortunate to be able to do so. I said that first I would have the Manual translated into Sinhala.

For this purpose, I obtained the willing help of two physiotherapists, formerly favourite students. By name Wettimuny Silva and Somadasa Mohettige. While they did the translation in their own homes in the evenings after work, we met at my dining table in my home in Swarna Road for joint sessions which, as you can imagine, were called for quite often. We had the Sinhala Manual ready in no time. Wetta and Some, as their friends called them, and I maintain the bond we established at that time and continue our friendship.

First Field Tests in Sri Lanka

Dudley had the necessary photocopies made. I was soon walking the two villages of Meegolla and Kahandawelipotha in the Kurunegala district with the two students of social work. They had selected between them 20 children who had disability all under the age of 14 years. At the end of the six months of the project, 19 of the 20 showed improvements. Some of those children still live vividly in my memory.

One was Mala, aged eight years, who had cerebral palsy. Her mother cared for her with utmost love. She bathed, dressed and fed Mala in the morning and sat her on a chair at a window. Mala spent her day watching passers-by on the road.

That was until the two students of social work came into their lives. Soon Mala was learning to walk using bars her father made in the garden using long bamboos. She was helping her mother in the kitchen. Children from the neighbourhood came to her house to play with her. Hopefully in a few months she would go to the village school. The students arranged for the local social service worker to come to see Mala. The social service worker will get a wheelchair for Mala.

Another was 11-year-old Nandani. She too did not go to school. Her parents could not see how she could do that, seeing she could not speak. But she could hear. Like Ntchadi in faraway Serowe in Botswana, she too looked on longingly when her young siblings went to school. Counselling from the students, an appointment with the principal and the education officer and Nandani was in school.

When we visited the school before the project ended, Nandani was already showing signs of leadership in the classroom. She was a bright girl. She will surely catch up with her peers before long.

Dudley shared with UNICEF Colombo the study and the results of the work of the students. He was able to secure from UNICEF formal support for the development of CBR as project studies for a number of his students over the next few years. But within three years UNICEF, with the Department of Social Work and the help of students, started a large CBR project in Anuradhapura district.

In time Dudley, climbing the administrative ladder step by step reached the Ministry of Social Welfare. It was first as Senior Assistant Secretary, then as Additional Secretary, and finally reached the peak as Secretary of the Ministry. Dudley took CBR there with him. Dudley had the Manual translated into Tamil and introduced its extended use in the North. From then on CBR grew within Government with generous allocations directly from the national budget.

Disability Studies Unit – Early Years in Sri Lanka

I shared with you in the section above how the University of Kelaniya, in 1993 with support from Sweden, set up the Disability Studies Unit or DSU and of my role in it. I also continued in that section to share with you my journey in disability during my time there, focusing on aspects of international work. This is a suitable time perhaps to reflect on my journey with the DSU in Sri Lanka.

It was Anoja Wijeyesekera, at the time a Programme Officer at UNICEF Colombo who introduced the DSU to the Ministry of Social Welfare. Viji Jegarasasingham was the Additional Secretary at the time. Mrs. J. was one dynamic lady with a mission. That mission was to ensure the effective functioning of her ministry and other institutions under her purview. She was later promoted as Secretary and held that post for many years until her retirement from Government service.

Viji Jegarajasingham, our Mrs J., set up within the Ministry a Resource Group on CBR with just five of us as members. One of them was Gihan Galekotuwa or Gale who was then the Disability Programme Head at the NGO Fridsro. Our Resource Group strengthened the relationship in disability work between this ministry and that of health and of employment. This was with the aim of planting the seed of multi-sectoral cooperation to benefit disabled people with a wider perspective of their rights.

Gale was convinced that CBR was the way to go if the rights of disabled children and adults were to be fulfilled with their inclusion and participation in their communities and in society at large. Fridsro had developed their CBR capacity by implementing CBR themselves in parts of the Central Province where they were located. Starting in Poojapitya Division and spreading to 11 others in the Kandy district. These were developed as learning and teaching areas.

Gale soon had Fridsro draw up an MOU with the Ministry of Social Welfare to provide technical and other support to the Ministry to improve their CBR programme both in quality and in coverage. This agreement and action continued for many years, even after I was no longer at the DSU.

Within a few years many disabled children and adults spread out in most of Sri Lanka’s districts had been reached. A change was being brought about in their lives, families and communities. Monitored continuously and evaluated at intervals by Fridsro.

Working with me at the DSU was Somadasa Kodikara, a former student of mine at the School of Physiotherapy. Representing the DSU “Kodi” and I worked with the Ministry and with Fridsro as a threesome to reach disabled people in more than 50% of Sri Lanka’s districts during those few years. The DSU had roles in both teaching and in monitoring. We soon learned that Sri Lanka government workers were loath to submit written reports. As for us, we were happy monitoring through field visits. For us it was any excuse to go to the people.

During our years together at the DSU, Kodi and I continued to evaluate the WHO Manual in the two languages with periodic revisions and continuous improvement. Fridsro provided financial support for publishing them in both languages for field use. Kodi and I also produced and published through the DSU much teaching-learning material for both community workers and for their divisional and district supervisors.

Soon after the DSU was born, we were invited to link up with the Global Disability Database maintained jointly by Uppsala University and AHRTAG in London. Before I left the DSU in 1998, we had an agreement drawn up with the International Health Unit of London University and the Hospital for Children, Great Ormond Street to start the Education of Speech and Language Therapists or SLTs.

. The DSU has come a long way. And it will continue its own journey as it grows unendingly.

Features

The hollow recovery: A stagnant industry – Part I

The headlines are seductive: 2.36 million tourists in 2025, a new “record.” Ministers queue for photo opportunities. SLTDA releases triumphant press statements. The narrative is simple: tourism is “back.”

The headlines are seductive: 2.36 million tourists in 2025, a new “record.” Ministers queue for photo opportunities. SLTDA releases triumphant press statements. The narrative is simple: tourism is “back.”

But scratch beneath the surface and what emerges is not a success story but a cautionary tale of an industry that has mistaken survival for transformation, volume for value, and resilience for strategy.

Problem Diagnosis: The Mirage of Recovery

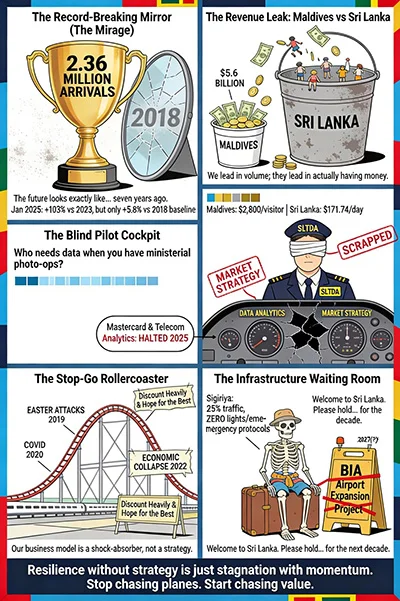

Yes, Sri Lanka welcomed 2.36 million tourists in 2025, marginally above the 2.33 million recorded in 2018. This marks a full recovery from the consecutive disasters of the Easter attacks (2019), COVID-19 (2020-21), and the economic collapse (2022). The year-on-year growth looks impressive: 15.1% above 2024’s 2.05 million arrivals.

But context matters. Between 2018 and 2023, arrivals collapsed by 36.3%, bottoming out at 1.49 million. The subsequent “rebound” is simply a return to where we were seven years ago, before COVID, before the economic crisis, even before the Easter attacks. We have spent six years clawing back to 2018 levels while competitors have leaped ahead.

Consider the monthly data. In 2023, January arrivals were just 102,545, down 57% from January 2018’s 238,924. By January 2025, arrivals reached 252,761, a dramatic 103% jump over 2023, but only 5.8% above the 2018 baseline. This is not growth; it is recovery from an artificially depressed base. Every month in 2025 shows the same pattern: strong percentage gains over the crisis years, but marginal or negative movement compared to 2018.

The problem is not just the numbers, but the narrative wrapped around them. SLTDA’s “Year in Review 2025” celebrates the 15.6% first-half increase without once acknowledging that this merely restores pre-crisis levels. The “Growth Scenarios 2025” report projects arrivals between 2.4 and 3.0 million but offers no analysis of what kind of tourism is being targeted, what yield is expected, or how market composition will shift. This is volume-chasing for its own sake, dressed up as strategic planning.

Comparative Analysis: Three Decades of Standing Still

The stagnation becomes stark when placed against Sri Lanka’s closest island competitors. In the mid-1990s, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, started from roughly the same base, around 300,000 annual arrivals each. Three decades later:

Sri Lanka: From 302,000 arrivals (1996) to 2.36 million (2025), with $3.2 billion

Maldives: From 315,000 arrivals (1995) to 2.25 million (2025), with $5.6 billion

The raw numbers obscure the qualitative difference. The Maldives deliberately crafted a luxury, high-yield model: one-island-one-resort zoning, strict environmental controls, integrated resorts layered with sustainability credentials. Today, Maldivian tourism generates approximately $5.6 billion from 2 million tourists, an average of $2,800 per visitor. The sector represents 21% of GDP and generates nearly half of government revenue.

Sri Lanka, by contrast, has oscillated between slogans, “Wonder of Asia,” “So Sri Lanka”, without embedding them in coherent policy. We have no settled model, no consensus on what kind of tourism we want, and no institutional memory because personnel and priorities change with every government. So, we match or slightly exceed competitors in arrivals, but dramatically underperform in revenue, yield, and structural resilience.

Root Causes: Governance Deficit and Policy Failure

The stagnation is not accidental; it is manufactured by systemic governance failures that successive governments have refused to confront.

1. Policy Inconsistency as Institutional Culture

Sri Lanka has rewritten its Tourism Act and produced multiple master plans since 2005. The problem is not the absence of strategy documents but their systematic non-implementation. The National Tourism Policy approved in February 2024 acknowledges that “policies and directions have not addressed several critical issues in the sector” and that there was “no commonly agreed and accepted tourism policy direction among diverse stakeholders.”

This is remarkable candor, and a damning indictment. After 58 years of organised tourism development, we still lack policy consensus. Why? Because tourism policy is treated as political property, not national infrastructure. Changes in government trigger wholesale personnel changes at SLTDA, Tourism Ministry, and SLTPB. Institutional knowledge evaporates. Priorities shift with ministerial whims. Therefore, operators cannot plan, investors cannot commit, and the industry lurches from crisis response to crisis response without building structural resilience.

2. Fragmented Institutional Architecture

Tourism responsibilities are scattered across the Ministry of Tourism, Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA), Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau (SLTPB), provincial authorities, and an ever-expanding roster of ad hoc committees. The ADB’s 2024 Tourism Sector Diagnostics bluntly notes that “governance and public infrastructure development of tourism in Sri Lanka is fragmented and hampered.”

Tourism responsibilities are scattered across the Ministry of Tourism, Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA), Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau (SLTPB), provincial authorities, and an ever-expanding roster of ad hoc committees. The ADB’s 2024 Tourism Sector Diagnostics bluntly notes that “governance and public infrastructure development of tourism in Sri Lanka is fragmented and hampered.”

No single institution owns yield. No one is accountable for net foreign exchange contribution after leakages. Quality standards are unenforced. The tourism development fund, 1% of the tourism levy plus embarkation taxes, is theoretically allocated 70% to SLTPB for global promotion, but “lengthy procurement and approval processes” render it ineffective.

Critically, the current government has reportedly scrapped sophisticated data analytics programmes that were finally giving SLTDA visibility into spending patterns, high-yield segments, and tourist movement. According to industry reports in late 2025, partnerships with entities like Mastercard and telecom data analytics have been halted, forcing the sector to fly blind precisely when data-driven decision-making is essential.

3. Infrastructure Deficit and Resource Misallocation

The Bandaranaike International Airport Development Project, essential for handling projected tourist volumes, has been repeatedly delayed. Originally scheduled for completion years ago, it is now re-tendered for 2027 delivery after debt restructuring. Meanwhile, tourists in late 2025 faced severe congestion at BIA, with reports of near-miss flights due to immigration and check-in bottlenecks.

At cultural sites, basic facilities are inadequate. Sigiriya, which generates approximately 25% of cultural tourist traffic and charges $36 per visitor, lacks adequate lighting, safety measures, and emergency infrastructure. Tourism associations report instances of tourists being attacked by wild elephants with no effective safety protocols.

SLTDA Chairman statements acknowledge “many restrictions placed on incurring capital expenditure” and “embargoes placed not only on tourism but all Government institutions.” The frank admission: we lack funds to maintain the assets that generate revenue. This is governance failure in its purest form, allowing revenue-generating infrastructure to decay while chasing arrival targets.

The Stop-Go Trap: Volatility as Business Model

What truly differentiates Sri Lanka from competitors is not arrival levels but the pattern: extreme stop-go volatility driven by crisis and short-term stimulus rather than steady, strategic growth.

After each shock, the industry is told to “bounce back” without being given the tools to build resilience. The rebound mechanism is consistent: currency depreciation makes Sri Lanka “affordable,” operators discount aggressively to fill rooms, and visa concessions attract price-sensitive segments. Arrivals recover, until the next shock.

This is not how a strategic export industry operates. It is how a shock-absorber behaves, used to plug forex and fiscal holes after each policy failure, then left exposed again.

The monthly 2023-2025 data illustrate the cycle perfectly. Between January 2018 and January 2023, arrivals fell 57%. The “recovery” to January 2025 shows a 103% jump over 2023, but this is bounce-back from an artificially depressed base, not structural transformation. By September 2025, growth rates normalize into the teens and twenties, catch-up to a benchmark set six years earlier.

Why the Boom Feels Like Stagnation

Industry operators report a disconnect between headline numbers and ground reality. Occupancy rates have improved to the high-60% range, but margins remain below 2018 levels. Why?

Industry operators report a disconnect between headline numbers and ground reality. Occupancy rates have improved to the high-60% range, but margins remain below 2018 levels. Why?

Because input costs, energy, food, debt servicing, have risen faster than room rates. The rupee’s collapse makes Sri Lanka look “affordable” to foreigners, but it quietly transfers value from domestic suppliers and workers to foreign visitors and lenders. Hotels fill rooms at prices that barely cover costs once translated into hard currency and adjusted for inflation.

Growth is fragile and concentrated. Europe and Asia-Pacific account for over 92% of arrivals. India alone provides 20.7% of visitors in H1 2025, and as later articles in this series will show, this is a low-yield, short-stay segment. We have built recovery on market concentration and price competition, not on product differentiation or yield optimization.

There is no credible long-term roadmap. SLTDA’s projections focus almost entirely on volumes. There is no public discussion of receipts-per-visitor targets, market composition strategies, or institutional reforms required to shift from volume to value.

The Way Forward: From Arrivals Theater to Strategic Transformation

The path out of stagnation requires uncomfortable honesty and political courage that has been systematically absent.

First, abandon arrivals as the primary success metric. Tourism contribution to economic recovery should be measured by net foreign exchange contribution after leakages, employment quality (wages, stability), and yield per visitor, not by how many planes land.

Second, establish institutional continuity. Depoliticize relevant leaderships. Implement fixed terms for key personnel insulated from political cycles. Tourism is a 30-year investment horizon; it cannot be managed on five-year electoral cycles.

Third, restore data infrastructure. Reinstate the analytics programs that track spending patterns and identify high-yield segments. Without data, we are flying blind, and no amount of ministerial optimism changes that.

Fourth, allocate resources to infrastructure. The tourism development fund exists, use it. Online promotions, BIA expansion, cultural site upgrades, last-mile connectivity cannot wait for “better fiscal conditions.” These assets generate the revenue that funds their own maintenance.

Resilience without strategy is stagnation with momentum. And stagnation, however energetically celebrated, remains stagnation.

If policymakers continue to mistake arrivals for achievement, Sri Lanka will remain trapped in a cycle: crash, discount, recover, repeat. Meanwhile, competitors will consolidate high-yield models, and we will wonder why our tourism “boom” generates less cash, less jobs, and less development than it should.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

The call for review of reforms in education: discussion continues …

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The statement by 94 university teachers deplores the high handed manner in which the reforms were hastily formulated, and without public consultation. It underlines the problems with the substance of the reforms, particularly in the areas of the structure of education, and the content of the text books. The problem lies at the very outset of the reforms, with the conceptual framework. While the stated conceptualisation sounds fancifully democratic, inclusive, grounded and, simultaneously, sensitive, the detail of the reforms-structure itself shows up a scandalous disconnect between the concept and the structural features of the reforms. This disconnect is most glaring in the way the secondary school programme, in the main, the junior and senior secondary school Phase I, is structured; secondly, the disconnect is also apparent in the pedagogic areas, particularly in the content of the text books. The key players of the “Reforms” have weaponised certain seemingly progressive catch phrases like learner- or student-centred education, digital learning systems, and ideas like moving away from exams and text-heavy education, in popularising it in a bid to win the consent of the public. Launching the reforms at a school recently, Dr. Amarasuriya says, and I cite the state-owned broadside Daily News here, “The reforms focus on a student-centered, practical learning approach to replace the current heavily exam-oriented system, beginning with Grade One in 2026 (https://www.facebook.com/reel/1866339250940490). In an address to the public on September 29, 2025, Dr. Amarasuriya sings the praises of digital transformation and the use of AI-platforms in facilitating education (https://www.facebook.com/share/v/14UvTrkbkwW/), and more recently in a slightly modified tone (https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking-news/PM-pledges-safe-tech-driven-digital-education-for-Sri-Lankan-children/108-331699).

The idea of learner- or student-centric education has been there for long. It comes from the thinking of Paulo Freire, Ivan Illyich and many other educational reformers, globally. Freire, in particular, talks of learner-centred education (he does not use the term), as transformative, transformative of the learner’s and teacher’s thinking: an active and situated learning process that transforms the relations inhering in the situation itself. Lev Vygotsky, the well-known linguist and educator, is a fore runner in promoting collaborative work. But in his thought, collaborative work, which he termed the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is processual and not goal-oriented, the way teamwork is understood in our pedagogical frameworks; marks, assignments and projects. In his pedagogy, a well-trained teacher, who has substantial knowledge of the subject, is a must. Good text books are important. But I have seen Vygotsky’s idea of ZPD being appropriated to mean teamwork where students sit around and carry out a task already determined for them in quantifying terms. For Vygotsky, the classroom is a transformative, collaborative place.

But in our neo liberal times, learner-centredness has become quick fix to address the ills of a (still existing) hierarchical classroom. What it has actually achieved is reduce teachers to the status of being mere cogs in a machine designed elsewhere: imitative, non-thinking followers of some empty words and guide lines. Over the years, this learner-centred approach has served to destroy teachers’ independence and agency in designing and trying out different pedagogical methods for themselves and their classrooms, make input in the formulation of the curriculum, and create a space for critical thinking in the classroom.

Thus, when Dr. Amarasuriya says that our system should not be over reliant on text books, I have to disagree with her (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/29/education-reform-to-end-textbook-tyranny ). The issue is not with over reliance, but with the inability to produce well formulated text books. And we are now privy to what this easy dismissal of text books has led us into – the rabbit hole of badly formulated, misinformed content. I quote from the statement of the 94 university teachers to illustrate my point.

“The textbooks for the Grade 6 modules . . . . contain rampant typographical errors and include (some undeclared) AI-generated content, including images that seem distant from the student experience. Some textbooks contain incorrect or misleading information. The Global Studies textbook associates specific facial features, hair colour, and skin colour, with particular countries and regions, and refers to Indigenous peoples in offensive terms long rejected by these communities (e.g. “Pygmies”, “Eskimos”). Nigerians are portrayed as poor/agricultural and with no electricity. The Entrepreneurship and Financial Literacy textbook introduces students to “world famous entrepreneurs”, mostly men, and equates success with business acumen. Such content contradicts the policy’s stated commitment to “values of equity, inclusivity and social justice” (p. 9). Is this the kind of content we want in our textbooks?”

Where structure is concerned, it is astounding to note that the number of subjects has increased from the previous number, while the duration of a single period has considerably reduced. This is markedly noticeable in the fact that only 30 hours are allocated for mathematics and first language at the junior secondary level, per term. The reduced emphasis on social sciences and humanities is another matter of grave concern. We have seen how TV channels and YouTube videos are churning out questionable and unsubstantiated material on the humanities. In my experience, when humanities and social sciences are not properly taught, and not taught by trained teachers, students, who will have no other recourse for related knowledge, will rely on material from controversial and substandard outlets. These will be their only source. So, instruction in history will be increasingly turned over to questionable YouTube channels and other internet sites. Popular media have an enormous influence on the public and shapes thinking, but a well formulated policy in humanities and social science teaching could counter that with researched material and critical thought. Another deplorable feature of the reforms lies in provisions encouraging students to move toward a career path too early in their student life.

The National Institute of Education has received quite a lot of flak in the fall out of the uproar over the controversial Grade 6 module. This is highlighted in a statement, different from the one already mentioned, released by influential members of the academic and activist public, which delivered a sharp critique of the NIE, even while welcoming the reforms (https://ceylontoday.lk/2026/01/16/academics-urge-govt-safeguard-integrity-of-education-reforms). The government itself suspended key players of the NIE in the reform process, following the mishap. The critique of NIE has been more or less uniform in our own discussions with interested members of the university community. It is interesting to note that both statements mentioned here have called for a review of the NIE and the setting up of a mechanism that will guide it in its activities at least in the interim period. The NIE is an educational arm of the state, and it is, ultimately, the responsibility of the government to oversee its function. It has to be equipped with qualified staff, provided with the capacity to initiate consultative mechanisms and involve panels of educators from various different fields and disciplines in policy and curriculum making.

In conclusion, I call upon the government to have courage and patience and to rethink some of the fundamental features of the reform. I reiterate the call for postponing the implementation of the reforms and, in the words of the statement of the 94 university teachers, “holistically review the new curriculum, including at primary level.”

(Sivamohan Sumathy was formerly attached to the University of Peradeniya)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Sivamohan Sumathy

Features

Constitutional Council and the President’s Mandate

The Constitutional Council stands out as one of Sri Lanka’s most important governance mechanisms particularly at a time when even long‑established democracies are struggling with the dangers of executive overreach. Sri Lanka’s attempt to balance democratic mandate with independent oversight places it within a small but important group of constitutional arrangements that seek to protect the integrity of key state institutions without paralysing elected governments. Democratic power must be exercised, but it must also be restrained by institutions that command broad confidence. In each case, performance has been uneven, but the underlying principle is shared.

Comparable mechanisms exist in a number of democracies. In the United Kingdom, independent appointments commissions for the judiciary and civil service operate alongside ministerial authority, constraining but not eliminating political discretion. In Canada, parliamentary committees scrutinise appointments to oversight institutions such as the Auditor General, whose independence is regarded as essential to democratic accountability. In India, the collegium system for judicial appointments, in which senior judges of the Supreme Court play the decisive role in recommending appointments, emerged from a similar concern to insulate the judiciary from excessive political influence.

The Constitutional Council in Sri Lanka was developed to ensure that the highest level appointments to the most important institutions of the state would be the best possible under the circumstances. The objective was not to deny the executive its authority, but to ensure that those appointed would be independent, suitably qualified and not politically partisan. The Council is entrusted with oversight of appointments in seven critical areas of governance. These include the judiciary, through appointments to the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal, the independent commissions overseeing elections, public service, police, human rights, bribery and corruption, and the office of the Auditor General.

JVP Advocacy

The most outstanding feature of the Constitutional Council is its composition. Its ten members are drawn from the ranks of the government, the main opposition party, smaller parties and civil society. This plural composition was designed to reflect the diversity of political opinion in Parliament while also bringing in voices that are not directly tied to electoral competition. It reflects a belief that legitimacy in sensitive appointments comes not only from legal authority but also from inclusion and balance.

The idea of the Constitutional Council was strongly promoted around the year 2000, during a period of intense debate about the concentration of power in the executive presidency. Civil society organisations, professional bodies and sections of the legal community championed the position that unchecked executive authority had led to abuse of power and declining public trust. The JVP, which is today the core part of the NPP government, was among the political advocates in making the argument and joined the government of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga on this platform.

The first version of the Constitutional Council came into being in 2001 with the 17th Amendment to the Constitution during the presidency of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. The Constitutional Council functioned with varying degrees of effectiveness. There were moments of cooperation and also moments of tension. On several occasions President Kumaratunga disagreed with the views of the Constitutional Council, leading to deadlock and delays in appointments. These experiences revealed both the strengths and weaknesses of the model.

Since its inception in 2001, the Constitutional Council has had its ups and downs. Successive constitutional amendments have alternately weakened and strengthened it. The 18th Amendment significantly reduced its authority, restoring much of the appointment power to the executive. The 19th Amendment reversed this trend and re-established the Council with enhanced powers. The 20th Amendment again curtailed its role, while the 21st Amendment restored a measure of balance. At present, the Constitutional Council operates under the framework of the 21st Amendment, which reflects a renewed commitment to shared decision making in key appointments.

Undermining Confidence

The particular issue that has now come to the fore concerns the appointment of the Auditor General. This is a constitutionally protected position, reflecting the central role played by the Auditor General’s Department in monitoring public spending and safeguarding public resources. Without a credible and fearless audit institution, parliamentary oversight can become superficial and corruption flourishes unchecked. The role of the Auditor General’s Department is especially important in the present circumstances, when rooting out corruption is a stated priority of the government and a central element of the mandate it received from the electorate at the presidential and parliamentary elections held in 2024.

So far, the government has taken hitherto unprecedented actions to investigate past corruption involving former government leaders. These actions have caused considerable discomfort among politicians now in the opposition and out of power. However, a serious lacuna in the government’s anti-corruption arsenal is that the post of Auditor General has been vacant for over six months. No agreement has been reached between the government and the Constitutional Council on the nominations made by the President. On each of the four previous occasions, the nominees of the President have failed to obtain its concurrence.

The President has once again nominated a senior officer of the Auditor General’s Department whose appointment was earlier declined by the Constitutional Council. The key difference on this occasion is that the composition of the Constitutional Council has changed. The three representatives from civil society are new appointees and may take a different view from their predecessors. The person appointed needs to be someone who is not compromised by long years of association with entrenched interests in the public service and politics. The task ahead for the new Auditor General is formidable. What is required is professional competence combined with moral courage and institutional independence.

New Opportunity

By submitting the same nominee to the Constitutional Council, the President is signaling a clear preference and calling it to reconsider its earlier decision in the light of changed circumstances. If the President’s nominee possesses the required professional qualifications, relevant experience, and no substantiated allegations against her, the presumption should lean toward approving the appointment. The Constitutional Council is intended to moderate the President’s authority and not nullify it.

A consensual, collegial decision would be the best outcome. Confrontational postures may yield temporary political advantage, but they harm public institutions and erode trust. The President and the government carry the democratic mandate of the people; this mandate brings both authority and responsibility. The Constitutional Council plays a vital oversight role, but it does not possess an independent democratic mandate of its own and its legitimacy lies in balanced, principled decision making.

Sri Lanka’s experience, like that of many democracies, shows that institutions function best when guided by restraint, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to the public good. The erosion of these values elsewhere in the world demonstrates their importance. At this critical moment, reaching a consensus that respects both the President’s mandate and the Constitutional Council’s oversight role would send a powerful message that constitutional governance in Sri Lanka can work as intended.

by Jehan Perera

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition