Opinion

IMF may have changed, but Sri Lanka has not

The IMF has told us in no uncertain terms that corruption and waste have to be brought under control. Yet, a minister would directly solicit a bribe from a Japanese company and get away with it. Doesn’t the Cabinet have any control over officials who change the conditions in the tender, and decide to buy coal for two years with no thought for the price fluctuations.Although the IMF, the Paris Club, the US, the UK, Europe, China and Japan have all got together to help us. Do we deserve their help? The corrupt system needs a shake-up.

The IMF was formed in 1945 at the Bretton Woods Conference based on the ideas of Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes. At the beginning it had 29 members. The objective was to expedite the economic development of underdeveloped countries. It focused on three areas – policy development, financial assistance and capacity development. The funds came mainly from the US, western countries and Japan. Keynesian policies, which did not discourage welfarism and government intervention in economic policies, initially benefited many developing countries and also the poor in rich countries. From the end of World War II to about the early 70s, these policies were not harmful to the global poor.

In the 70s Margaret Thatcher came to power in Britain and Ronald Reagan in the US. They were of the opinion that welfarism and government role were an impediment to economic development. The basis of neo-liberalism is the idea that the market is the prime determinant of not only prices of goods, and matters related to trade and commerce, but also social characters and human values. This means there is no need for the government to intervene on behalf of the people, and market forces most efficiently guide the economy with benefits to all stakeholders. This theory was first mooted by Friedrich von Hayek, and it was more or less a refutation of welfare capitalism advocated by John Maynard Keynes, which had been in practice since the end of Word War II in 1945. Hayek advised Margaret Thatcher on the virtues of neo-liberal economic policies, and those were subsequently adopted during Reagan’s time in the US and Margaret Thatcher’s in the UK.

These policies virtually detached the government from economic management. During the era of welfare capitalism and Keynesianism, which existed from the late 40s to the early 70s, the governments in the western countries adopted measures to protect the ordinary people from the depredations of market forces. Reagan and Thatcher, however, viewed those policies as an impediment to economic development. They believed that unrestrained market forces were a better driver of the economy. Thus were born neo-liberalism and its offshoot globalisation, which was designed to force the rest of the world to fall in line and accept their open-borders, export-led growth policy. The IMF, WTO and the World Bank were reoriented to serve this purpose.

These neo-liberal policies prevailed until the outbreak of the international debt crisis in 1982. In the latter half of the 1970s, developing countries borrowed heavily to pay for increasingly costly oil imports and to finance ambitious investment projects, many of which turned out to be white elephants. The IMF traced their problems to poor policies, unproductive borrowing, and incomplete programme implementation. In disbursing funds, the IMF became more selective about the recipients of concessional support, and required stricter and more extensive conditionality.

The 1980s the world learnt that a programme was unlikely to succeed if the impact of economic reforms on the poor—and resulting social unrest and opposition—was not addressed. This prompted the IMF to focus its help not only on poor countries, but also on the poor within countries. Analysis of poverty issues in Policy Framework Papers became a standard part of programme negotiations. Programmes continued to emphasise fiscal consolidation as a prerequisite for macroeconomic stability, but there were growing pledges to strengthen social spending, especially for health and education.

In the meantime, however, many low-income countries faced the problem of debt accumulation beyond their repaying capacity. In 1996, the IMF and the World Bank developed the Heavily Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) initiative, under which low-income countries with multi-year track records of good policies, would qualify for grants in association with their concessional loans.

The HIPC initiative soon came under heavy criticism for “offering too little relief too slowly to too few,” with only four countries obtaining a full stock of available debt relief before the end of the century. In 1999, the Bretton Woods institutions “enhanced” the initiative, by lowering the bar for judging whether debt was unsustainable, and providing debt relief and grants sooner to qualifying countries. Within three years, enhanced HIPC could deliver almost US$1 billion in debt relief to 25 countries.

By the turn of the century, the IMF’s engagement with low-income countries centered on three pillars: better funded and designed programmes, debt relief to facilitate poverty reduction efforts, and technical assistance. Although the IMF had long offered technical assistance to its members, the focus shifted to African countries, which by the early 2000s were receiving more than one-quarter of the IMF’s technical assistance. These efforts paid rich dividends. By 2019, 36 out of 39 eligible countries had received debt relief totaling some $125 billion, allowing them to increase social spending, especially on health and education, while remaining within budgetary envelopes. While most did not fully achieve their UN Millennium Development Goals, many made substantial progress.

Sri Lanka, to begin with, was better in terms of economic development than the African countries. It achieved middle income status. From 2010 to 2015 it recorded the highest GDP growth in South Asia, and was well on the way to prosperity. But the economy was like a wounded animal, burdened with so many unproductive projects and huge unsustainable debts. We were living beyond our means. Consumerism and aggrandizement became the order of the day. Few blunders by the government in 2020 and 2021 made the economy go bankrupt.

Apart from living beyond means, corruption, bribery, mismanagement and waste ate in to the vitals of the country. Yahapalana committed the Treasury bond scams. Then came the sugar scam under the new regime. And the most recent coal scam. Nether politicians nor bureaucrats have changed!

The IMF has told us in no uncertain terms that corruption and waste have to be brought under control. Yet, a minister would directly solicit a bribe from a Japanese company and get away with it. Doesn’t the Cabinet have any control over officials who change the conditions in the tender, and decide to buy coal for two years with no thought for the price fluctuations.Although the IMF, the Paris Club, the US, the UK, Europe, China and Japan have all got together to help us. Do we deserve their help? The corrupt system needs a shake-up.

N.A.de S. AMARATUNGA

Opinion

Remembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

Salute to a brave father-son

Cedric Martenstyn was a very affluent man. He owned a house in Colombo 7, valuable properties throughout the country, vehicles / speed boats and ran the lucrative business of importing Johnson and Evinrude Outboard Motors (OBM) and sold them to local fishermen and businessmen.

Cedric was the local agent for the OBMs, which were known for reliability and after-sales service, and among his customers were humble fishermen. He was fondly known as Sudu Mahattaya “(white Gentleman) by humble fishermen and he would often travel in his double cab across the country to meet his customers and solve their problems.

He had a loving wife and children. He was an excellent scuba diver, member of Sri Lanka Navy Practical Pistol Firing team and his knowledge of wildlife and reptiles was amazing.

A member of the Dutch Burgher community of Sri Lanka, he was a true patriot, who volunteered to protect country and people from terrorists. An old boy of S. Thomas’ College, Mount Lavinia, he was an excellent sportsman.

The founding father of Sri Lanka Army Commando Unit, Colonel Sunil Peris, was his classmate at S.Thomas’.

I first met Cedric when I was a very junior officer at Pistol Firing Range at Naval Base, Welisara. I helped him catch a poisonous snake in the Range. I think he carried that snake home in a bottle! That was the type of person Cedric was!

We became very close friends as we both loved “guns and fishing rods”. His experience and tactics in angling helped me catch much bigger Paraw (Trevallies) in the Elephant Rock area at the Trincomalee harbour. He was a dangerous man to live with at Trincomalee Naval Base wardroom (officers’ mess), because he had various live snakes kept in bottles and fed them with little frogs!

Even though he was a keen angler, he was keen to conserve endangered species both on land and in water. He spent days in Horton Plains and the Knuckles Mountain Range streams to identify freshwater species in Sri Lanka. Did you know there is an endangered freshwater fish species he found in Horton Plains and Knuckles Mountain Range has been named after him?

Feeding of snakes was an amusement to all our stewards at the wardroom at that time! They all gathered and watched carefully what Cedric was doing, keeping a safe distance to run away if the snake escaped. Our Navy stewards dare to enter Cedric’s cabin (room) at Trincomalee wardroom (officers’ mess), even keeping his tea on a stool outside his cabin door. One day pandemonium broke in the officers’ mess when Cedric announced that one snake escaped! We never found that snake, and that was the end of his hobby as the Commander Eastern Naval Area, at that time, ordered him to ” get rid of all snakes! Sadly, Cedric released all snakes to Sober Island that afternoon.

Cedric was a volunteer Navy officer, but still joined me (he was 47 years old then) to help SBS trainees (first and second batch) on boat handling and OBM maintenance in 1993, when I raised SBS. It was exactly 31 years ago!

The Arrow Boat

Being an excellent speed boat race driver and boat designer, he prepared the blueprint of the first “18-foot Arrow Boat” and supervised building it at a private Boat Yard in 1993. This 18- foot Arrow Boat was especially designed to be used in the shallow waters of the Jaffna lagoon, fitted 115 HP OBMs, and with two weapons he recommended; 40mm Automatic Grenade Launcher (AGL) and 7.62×51 mm General Purpose Machine Guns (GPMGs). In no time, we had highly trained and highly motivated four SBS men on board each Arrow Boat at Jaffna lagoon, and they were very effective.

Same hull (deep V hull) developed during the tenure of Admiral of the Fleet Wasantha Karannagoda, as Commander of the Navy, by Naval architects, with knowledge-gained through captured LTTE Sea Tiger boats, designed 23- foot Arrow Boats and implemented the “Lanchester Theory” (theory of battle of attrition at sea in littoral sea battles) to completely nullify LTTE’s superiority which it had gained with small craft and deadly suicide boats.

Thank you, the Admiral of the Fleet for understanding the importance of Arrow Boat design and mass production at our own boatyard at Welisara. Karannagoda, under whom I was fortunate to serve as Director Naval Operations, Director Maritime Surveillance and Director Naval Special Forces during the last stages (2006/7) of the Humanitarian Operations, always used to tell us “You cannot buy a Navy- you have to build one”! Thank you, Sir!

Cedric craft display at Naval Museum, Trincomalee

The Hero he was

When I was selected for my Naval War Course (Staff Course) conducted by the Pakistan Navy Staff College at Karachi, Pakistan, (now known as Pakistan Navy War College relocated at Lahore), Cedric took over the command (even though he was a VNF officer) as Commanding Officer of SBS.

Being one of the co-founders of this elite unit, he was the most suitable person to take over as CO SBS. He was loved by SBS officers and sailors. They were extremely happy to see him at Kilali or Elephant Pass, where SBS was deployed during a very difficult time of our recent history – fighting against terrorists during the 1996-97 period.

Motivated by father’s patriotism, his younger son, Jayson, who was a pilot working in the UK at that time, came back to Sri Lanka and joined the SLAF as an volunteer pilot to fly transport aircraft to keep an uninterrupted air link between Palaly (Jaffna) and Ratmalana (Colombo). Sometimes Jayson flew his beloved father on board from Palaly to Ratmalana. Cedric was extremely happy and proud of his son.

Tragically, young Jayson was killed in action in a suspected LTTE Surface-to-Air missile attack on his aircraft. Cedric was sad, but more determined to continue the fight against LTTE terrorists. He would also lead the rescue and salvage operation to identify the aircraft wreckage his son flew in. The then Navy Commander advised him to demobilise from VNF and look after his grieving family or join Naval Operations Directorate and work from Colombo which he vehemently refused. When I called him from Pakistan to convey my deepest condolences, he said, he would look after the “SBS boys”, he had no intention of leaving them alone at that difficult hour of our nation. That was Cedric. He was such a hero—a hero very few knew about!

The young officers, and sailors in SBS were of his sons’ age, and Cedric would not leave them even when he was facing a personal tragedy. He was a dedicated and courageous person.

Scientific name: Systomus Martenstyni

English name : Martenstyn’s Barb

Local name: Dumbara Pethiya

Sadly, like many who served our nation and stood against terrorists, Cedric would go on to be considered Missing In Action (MIA) following a helicopter crash off the seas of Vettalikani with Lt. Palihena (another brave SBS officer- KDU intake). He was returning to Point Pedro after visiting the SBS boys at Elephant Pass, Jaffna.

Cedric and his son, Jayson, will go down in history as a brave father-son duo who paid the supreme sacrifice for the motherland. MAY THEY REST IN PEACE ! Salute!

Commander Martenstyn was considered missing in action (MIA) on 22 January 1996 in the sea off Vettalaikerni, while returning to Palaly Air Force Base in an SLAF helicopter when it was lost to enemy fire. He was returning from visiting an SBS detachment in Elephant Pass near the Jaffna Lagoon. Considering his contribution to the war effort, his gallentry and valour in fighting the enemy, and his steadfast service to the Sri Lanka Navy in manufacturing Arrow Boats, and training the SBS, all SLN Arrow Boats were renamed ‘Cedric’ on his 70th Birthday.

(The writer is former Chief of Defence Staff and Commander of The Navy, and former Chairman of the Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd.)

By Admiral Ravindra

C Wijegunaratne

(Retired from Sri Lanka Navy)

Former Chief of Defence Staff and Commander of the Sri Lanka Navy,

Former Sri Lanka High Commissioner to Pakistan

Opinion

History of St. Sebastian’s National Shrine Kandana

According to legend, St. Sebastian was born at Narbonne in Gaul. He became a soldier in Rome and encouraged Marcellian and Marcus, who were sentenced to death, to remain firm in their faith. St. Sebastian made several converts; among them were master of the rolls Nicostratus, who was in charge of prisoners, and his wife Zoe, a deaf mute whom he cured.

Sebastian was named captain in the Roman army by Emperor Diocletian, as by Emperor Maximian when Diocletian went to the east. Neither knew that Sebastian was a Christian. When it was discovered that Sebastian was indeed a Christian, he was ordered to be executed. He was shot with arrows and left to die but when the widow of St. Castulas went to recover his body, she found out that he was still alive and nursed him back to health. Soon after his recovery, St. Sebastian intercepted the Emperor; denounced him for his cruelty to Christians and was beaten to death on the Emperor’s order.

St. Sebastian was venerated in Milan as early as the time of St. Ambrose. St. Sebastian is the patron of archers, athletes, soldiers, the Saint of the youths and is appealed to protection against the plagues. St. Ambrose reveals that the parents that young Sebastian were living in Milan as a noble family. St. Ambrose further says that Sebastian, along with his three friends, Pankasi, Pulvius and Thorvinus, completed his education successfully with the blessing of his mother, Luciana. Rev. Fr. Dishnef guided him through his spiritual life. From his childhood Sebastian wanted to join the Roman army. With the help of King Karnus, young Sebastian became a soldier and within a short span of time he was appointed as the Commander of the army of King Karnus. The Emperor Diocletian declared Christians the enemy of the Roman Empire and instructed judges to punish Christians who have embraced the Catholic Church. Young Sebastian, as one of the servants of Christ, converted thousands of other believers into Christians. When Emperor Diocletian revealed that Sebastian had become a Catholic, the angry Emperor ordered for Sebastian to be shot to death with arrows. After being shot by arrows, one of Sebastian supporters, Irane, treated him and cured him. When Sebastian was cured he went to Emperor Diocletian and professed his faith for the second time disclosing that he is a servant of Christ. Astounded by the fact that Sebastian is a Christian, Emperor Diocletian ordered the Roman army to kill Sebastian with club blows.

In the liturgical calendar of the Church, the feast of the St. Sebastian is celebrated on the 20th of January. This day is indeed a mini Christmas to the people of Kandana, irrespective of their religion. The feast commenced with the hoisting of the flag staff on the 11th of January at 4 p.m. at the Kandana junction, along the Colombo-Negombo road. There is a long history attached to the flag staff. The first flag staff, which was an areca nut tree, 25 feet tall, was hoisted by the Aththidiya family of Kandana, and today their descendants continue hoisting of the flag staff as a tradition. This year’s flag staff, too, was hoisted by the Raymond Aththidiya family. Several processions, originating from different directions, carrying flags, meet at this flag staff junction. The pouring of milk on the flag staff has been a tradition in existence for a long time. The Nagasalan band was introduced by a well-known Jaffna businessman that had engaged in business in Kandana in the 1950s. The famous Kandaiyan Pille’s Nagasalan group takes the lead, even today, in the procession. Kiribath Dane in the Kandana town had been a tradition from time immemorial.

According to available history from the Catholic archives and volume III of the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka, the British period of vicariates of Colombo, written by Rev. Ft. Vito Perniola SJ, in 1806, states that the British government granted the freedom of conscious and religion to the Catholics in Ceylon and abolished all the anti-Catholic legislation enacted by the Dutch.

The proclamation was declared and issued on the 3rd of August 1796 by Colonel James Stuart, the officer commanding the British forces of Ceylon stated “freedom granted to Catholics” (Sri Lanka national archives 20/5).

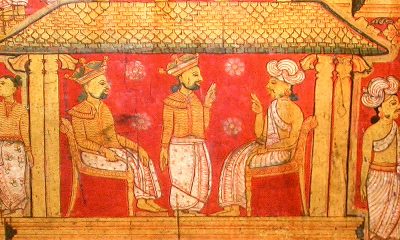

Before the Europeans, the missioners were all Goans from South India. In the year 1834, on the 3rd of December, XVI Gregory the Pope, issued a document Ex Muwere pastoralis ministeric, after which the Ceylon Catholic Church was made under the South Indian Cochin diocese. Very Rev. Fr. Vincent Rosario, the Apostolic Vicar General, was appointed along with 18 Goan priests (The Oratorion Mission in Sri Lanka being a history of the Catholic Chruch 1796-1874 by Arthur C Dep Chapter 11 pg 12). Rev Fr. Joachim Alberto arrived in Sri Lanka as missionary on the 6th of March 1830 when he was 31 years old and he was appointed to look after the Catholics in Aluthkuru Korale, consisting Kandana, Mabole, Nagodaa and Ragama. There have been one Church built in 1810 in Wewala about three miles away from Kandana. The Wewala Chruch was situated bordering Muthurajawela which rose to fame for its granary. History reveals that the entire area was under paddy cultivation and most of them were either farmers or toddy tappers. History further reveals that there has been an old canal built by King Weera Parakrama Bahu. Later it was built to flow through the Kelani River, and Muthurajawela, up to Negombo, which was named as the Dutch Canal (RL Brohier historian). During the British time this canal was named as Hamilton Canal and was used to transport toddy, spices, paddy and tree planks of which tree planks were stored in Kandana. Therefore, the name Kandana derives from “Kandan Aana”.

Rev. Fr. Joachim Alberto purchased a small piece of land, called Haamuduruwange watte, at Nadurupititya, in Kandana, and put up a small cadjan chapel and placed a picture of St. Sebastian for the benefit of his small congregation. In 1837, with the help of the devotees, he dug a small well where the water was used for drinking and bathing and today this well is still operative. He bought several acres of land, including the present cemetery premises. Moreover, he had put up the Church at Kalaeliya in honour of his patron St. Joachim where his body has been laid to rest according to his wish of the Last Will attested by Weerasinghe Arachchige Brasianu Thilakaratne. Notary Public, dated 19th July 1855. The present Church was built on the property bought on the 13th of August 1875 on deed no. 146 attested by Graciano Fernando. Notary Public of the land Gorakagahawatta Aluthkuru Korale Ragam Pattu in Kandana within the extend ¼ acre from and out of the 16 acres. According to the old plan number 374 made by P.A. H. Philipia, Licensed surveyor on the 31st of January 195, 9 acres and 25 perches belonged to St. Sebastian Church. However, today only 3 acres, 3 roods and 16.5 perches are left according to plan number 397 surveyed by the same surveyor, while the rest had been sold to the villagers. According to the survey conducted by Orithorian priest on the 12th of February 1844 there were only 18 school-going Catholic students in AluthKuru Korale and only one Antonio was the teacher for all classes. In 1844 there was no school at Kandana (APF SCG India Volume 9829).

According to Sri Lanka National Archives (The Ceylon Almanac page 185) in the year 1852 there were 982 Catholics Male 265, female 290, children 365, with a total of 922. According to the census reports in 2014, prepared by Rev. Ft. Sumeda Dissanayake TOR, the Director Franciscan Preaching group, Kadirana Negombo a survey revealed that there are 13,498 Catholics in Kandana.

According to the appointment of the Missionaries in the year 1866-1867 by Bishop Hillarien Sillani, Rev. Fr. Clement Pagnani OSB was sent to look after the missions in Negoda, Ragama, Batagama, Thudella, Kandana, Kala Eliya and Mabole. On the 18th of April 1866, the building of the new Church commenced with a written agreement by and between Rec. Fr. Clement Pagnani and the then leaders of Kandana Catholic Village Committee. This committee consisted of Kanugalawattage Savial Perera Samarasinghe Welwidane, Amarathunga Arachchige Issak Perera Appuhamy, Jayasuriya Arachchige Don Isthewan Appuhamy, Jayasuriya Appuhamylage Elaris Perera Muhuppu, Padukkage Andiris Perera Opisara, Kanugalawattage Peduru Perera Annavi and Mallawa Arachchige Don Peduru Appujamy. The said agreement stated that they will give written undertaking that their labour and money will be utilised to build the new Church of St. Sebastian and if they failed to do so they were ready to bear any punishment which will be imposed by the Catholic Church.

Rev. Fr. Bede Bercatta’s book “A History of the Vicariate of Colombo page 359” says that Rev. Fr. Stanislaus Tabarani had problems of finding rock stones to lay the foundation. He was greatly worried over this and placed his due trust in divine providence. He prayed for days to St. Sebastian for his intercession. One morning after mass, he was informed by some people that they had seen a small patch of granite at a place in Rilaulla, close to the Church premises, although such stones were never seen there earlier, and requested him to inspect the place. The parish priest visited the location and was greatly delighted as his prayers has been answered. This small granite rock amount provided enough granite

blocks for the full foundation of the present church. This place still known as “Rilaulla galwala”. The work on the building proceeded under successive parish priests but Rev. Fr. Stouter was responsible for much of it. The façade of the Church was built so high that it crashed on the 2nd of April of 1893. The present façade was then built and completed in the year 1905. The statue of St. Sebastian, which is behind the altar, had been carved off a “Madan tree”. It was done by a Paravara man, named Costa Mama, who was staying with a resident named Miguel Baas a Ridualle, Kandana. This statue was made at the request of Pavistina Perera Amaratunge, mother of former Member of Parliament gatemuadliyer D. Panthi Jayasuirya. The Church was completed during the time of Rev. Fr. Keegar and was blessed by then Archbishop of Colombo Dr. Anthony Courdert OMI on the 20th of January 1912. In 1926, Rev. Fr. Romauld Fernando was appointed as the parish priest to the Kandana Church. He was an educationalist and a social worker. Without any hesitation he can be called as the father of education to Kandana. He was the pioneer to build three schools in Kandana: Kandana St. Sebastian Boys School, Kandana St. Sebastian English Girls School and, the Mazenod College Kandana. Later he was appointed as the Principal of the St. Sebastian Boys English School. He bought a property at Kandana, close to Ganemulla Road, and started De Mazenod College. Later, it was given officially to the Christian Brothers of Sri Lanka, by then Archbishop of Colombo, Peter Mark. In 1931, there were 300 students (history of De Lasalle brothers by Rev. Fr. Bro Michael Robert). Today, there are over 3,500 students and is one of the leading Catholic schools in Sri Lanka. In 1924, one Karolis Jayasuriya Widanage donated two acres to build De Mazenod College for its extension.

The frist priest from Kandana to be ordained was Rev. Fr. William Perera in 1904. With the help of Rev. Fr. Marcelline Jayakody, he composed the famous hymn “the Vikshopa Geethaya”, the hymn of our Lady of Sorrow.

The Life story of St. Sebastian was portrayed through a stage play called “Wasappauwa” and the world famous German passion play Obar Amargavewchi whichwas a sensation was initiated by Rev. Fr. Nicholas Perera. Legend reveals that in the year 1845 a South Indian Catholic, on his way to meet his relatives in Colombo, had brought down a wooden statue of St. Sebastian, one and half feet tail, to be sold in Sri Lanka. When he reached Kalpitiya he had unexpectedly contracted malaria. He had made a vow at St. Anne’s Church, Thalawila, expecting a full recovery. En route to Colombo, he had come to know about the Church in Kandana and dedicated to St. Sebastian. In the absence of the then parish Priest Rev. Fr. Joachim Alberto, the Muhuppu of the Church, with the help of the others, had agreed to by the statue for 75 pathagas (one pahtaga was 75 cent). Even though the seller had left the money in the hands of the “Muhuppu” to be collected later, he never returned.

On the 19th of January 2006, Archbishop Oswald Gomis declared St. Sebastian Church as “St. Sebastian Shrine” by way of a special notification and handed over the declaration to Rev. Fr. Susith Perera, the Parish Priest of Kandana.

On the 12th of January 2014, Catholics in Sri Lanka celebrated the reception of a reliquary containing a fragment of the arm of St. Sebastian. The reliquary was gifted from the administrator of the Basilica of St. Anthony of Padua and was brought to Sri Lanka by Monsignor Neville Perera. His Eminence Malcolm Cardinal Ranjit, Archbishop of Colombo, accompanied by priests and a large gathering, received the relic at the Katunayake International Airport, and brought it to Kandana, led by a procession, and was enthroned at the St. Sebastian Shrine.

Rev. Fr. Srinath Manoj Perera, the present administrator of the shrine, and assistant Priest Rev. Fr. Asela Mario, have finalised all arrangements to conduct the feast of St. Sebastian in a grand scale.

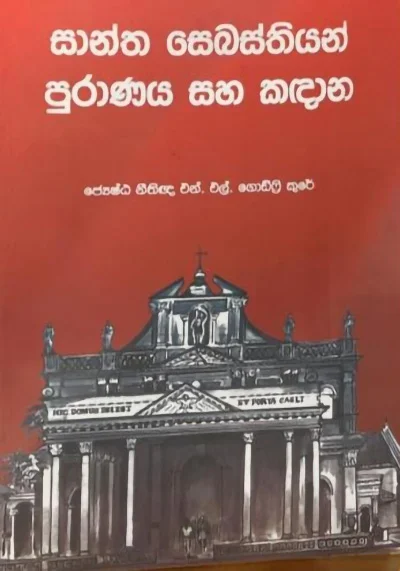

The latest book, written by Senior Lawyer Godfrey Cooray, named “Santha Sebastian Puranaya Saha Kandana” (The history of St. Sebastian and Kandana), was launched at De La Salle Auditorium, De Mazenod College, Kandana.

The Archbishop of Colombo His Eminence Most rev. Dr. Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith was the Chief Guests at the event.

The book discusses about the buried history of Muthurajawela and Aluth Kuru Korale civilisation, the history of Kandana and St. Sebastian. The author discusses the historical and archaeological values and culture.

158th Annual Feast of St. Sebastian’s National Shrine, Kandana, will be held on 20th of January 2026. On the 19th of January, Monday, Solemn Vespers were presided by His Lordship most Rev. Dr. Maxwell Silva Auxiliary Bishop of Colombo.

Festive High Mass will be presided by His Lordship Most Rev. Dr. J. D. Anthony, The Auxiliary Bishop of Colombo, on the 20th of January at 8pm.

By Godfrey Cooray

Senior Attorney -at -Law,

Former Ambassador to Norway and Finland

President, National Catholic Writers’ Association

Opinion

American rulers’ hatred for Venezuela and its leaders

The long-standing desire of the United States to subjugate, control, or overthrow the Venezuelan government has been driven primarily by two interconnected factors. The first is Venezuela’s vast mineral wealth, and the second is the emergence of anti-Imperialist and leftist political leadership that has consistently challenged US dominance in the region.

This hostility intensified dramatically in 1999, when Hugo Chávez—an outspoken leftist leader inspired by the legacy of Simón Bolívar, the father of Latin American independence from Spanish colonial rule—came to power. Chávez initiated a historic process of reclaiming Venezuela’s natural resources from US corporations and returning them to the Venezuelan people. From that moment onward, Venezuela became a central target of US imperial strategy.

Venezuela was one of the five founding members of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and became the world’s eighth-largest oil producer. The country possesses the largest proven oil reserves globally, estimated at 303 billion barrels. Beyond oil, Venezuela also plays a major role in heavy industries such as steel, aluminum, and cement. Its total mineral wealth is estimated at nearly US$14 trillion, and approximately 95 percent of its exports are derived from mineral resources.

Prior to the Chávez era, more than 500 US companies operated in Venezuela, dominating its extractive industries and using the country as a captive market for American exports. This economic dominance was directly challenged under Chávez and later under his political and ideological successor, President Nicolás Maduro. As a result, Venezuela increasingly came into conflict with US strategic and corporate interests.

Over the past two decades, the United States has directly, or indirectly, intervened in several oil-producing nations, including Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, and Libya. In some cases, rulers were assassinated and replaced with pro-American puppet regimes. Saudi Arabia, by aligning itself completely with US interests, has avoided invasion and survives as a compliant client state.

Venezuela, however, has stood firm for more than 20 years as a major obstacle to US efforts to dominate the global oil market. In this resistance, President Nicolás Maduro has emerged as one of the region’s most prominent anti-imperialist leaders.

After assuming office in 2013, President Maduro took decisive measures to counter the impact of long-standing US sanctions. Despite sanctions that disrupted nearly 50 percent of essential medicine supplies, Venezuela succeeded in rebuilding its pharmaceutical sector. By 2016, the country was producing approximately 80 percent of its essential medicines domestically. This policy of resistance and non-submission prompted the United States to escalate its pressure through new mechanisms, including direct restrictions on oil exports—which was called “oil quarantine.”

One notable incident in this campaign was the seizure of a commercial vessel by the US Coast Guard on December 10, while it was transporting Venezuelan petroleum to Cuba.

Simultaneously, the US intensified military provocations in Venezuelan maritime zones, including attacks on small naval vessels under the pretext of combating drug trafficking. US Senator Chris Coons himself acknowledged that more than 20 Venezuelan vessels had been destroyed and over 80 people killed under those operations, allegedly on the grounds of drug interdiction.

Beginning in early 2020, Venezuela and its leadership were formally accused of involvement in drug trafficking. In October of that year, a US federal court conducted a one-sided trial and convicted President Nicolás Maduro of “narco-terrorism” and conspiracy to import cocaine into the United States. This legal farce culminated in August 2025 with the announcement of a US$50 million bounty for the capture of President Maduro.

Many political analysts warned that these measures were designed to pave the way for a direct invasion and the arrest of Venezuela’s legitimate head of state. These warnings proved accurate, when On September 6, a Bill introduced in the US Senate, ostensibly to require congressional approval for military action against Venezuela, was defeated. Its rejection effectively granted the US president the authority to launch military operations against Venezuela without congressional consent.

Yet the central justification for these actions—drug trafficking—has been contradicted by official US sources themselves. According to reports by the US Drug Enforcement Administration, neither Venezuela nor President Maduro appears on the list of countries, or leaders, posing a drug-trafficking threat to the United States. Furthermore, the 2025 World Drug Report identifies the United States as the world’s largest drug market and distribution hub. Drug consumption, trafficking, and profit circulation are deeply embedded within the American economy itself.

It is, therefore, evident that the accusations against President Nicolás Maduro are false and politically motivated. Their real purpose is to legitimize invasion, regime change, and the arrest of a leader of a sovereign country. Parallel to this strategy, the US has consistently attempted to destabilise Venezuela internally. Opposition figures such as María Corina Machado were promoted to incite unrest using the “colour revolution” model. Her subsequent international recognition for these actions reveals the extent to which violence and destabilisation have been repackaged as “democracy promotion.”

These destabilisation efforts have been partly facilitated by unresolved structural weaknesses in Venezuela’s socio-economic system. Nearly 88 percent of the population resides in urban areas, while agriculture contributes only about 4 percent to the national economy. During periods of high inflation, low-income urban populations are the most vulnerable and, consequently, the most susceptible to manipulation for political unrest.

Another decisive factor behind US hostility is Venezuela’s strategic partnership with China. Under both Chávez and Maduro, Venezuela became China’s fourth-largest oil supplier. The China–Venezuela Joint Fund, established with the China Development Bank, financed major infrastructure projects. China extended a US$10 billion concessional loan during the 2010 financial crisis and later signed a US$16 billion agreement for joint oil venture for 450,000 barrels of oil per day. These developments significantly intensified American opposition.

The culmination of this entire process marks an unprecedented moment in world history: a powerful sovereign state invading another sovereign state without provocation, attacking civilian and military targets, killing more than 80 civilians, and forcibly removing the legitimate president from the country. While previous regime-change operations in Iraq and Libya followed prolonged military invasions justified by fabricated narratives, the arrest of President Nicolás Maduro represents an even more dangerous precedent.

Even more alarming is the paralysis of the United Nations, which has failed to convene either the Security Council or the General Assembly to address this blatant violation of international law.

Although China and Russia have publicly opposed US aggression, the silence and inaction of global institutions threaten to erode faith in international law itself.

This situation sets a grave precedent and poses a serious danger to world peace. It underscores the urgent need to build global public opinion in favor of sovereignty, non-intervention, and the formation of a new international anti-imperialist alliance.

by Dr. Wasantha Bandara

General Secretary

Patriotic National Movement

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoUNDP’s assessment confirms widespread economic fallout from Cyclone Ditwah

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoCrime and cops

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoThe Chakka Clash

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Story of Furniture in Sri Lanka