Features

Friends I made along the way, meeting in Colombo and on to Malaysia

(Excerpted from Memories that linger: My Journey in the World of Disability by Padmani Mendis)

Barbara McNamee was from Jamaica. She became my friend when we met in the month of October in 1958 as student nurses at the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital (ROH) in Birmingham, England. I have shared memories of our time together then in an earlier part of this memoir. We had been together for five years and three months. Mahin and Lyda both from Iran, then Persia were also with us.

The four of us became good friends during our first few days at the ROH. And we have remained close friends since then. In those first months, two calypso songs were particularly popular in the UK. They had just been released by the singer Harry Belafonte and were both about Jamaica. I enjoyed singing these to Barbara, especially when I saw that she was feeling a little low. One, “Island In The Sun” I mentioned a little earlier in this section. You may have heard the other “Jamaican Farewell”. They are available on YouTube. I occasionally send these to Barbara on WhatsApp just to remind her of the old days.

Barbara met Mike Rogers while she was at the ROH and he was a post-grad student at the University of Birmingham. They married soon after we completed our physiotherapy education. They had two children and spent the larger part of their lives in England.

Mahin left Iran much later to live in the USA and is now in Canada. She first had an Iranian husband and then an Egyptian one. Three stepsons living also in Toronto look out for her. Lyda also married an Englishman, Lewin Harris, and settled down in England. She passed on a few years ago. Barbara, Mahin and I still communicate regularly.

We last met five years ago. Mahin and I spent two weeks with Barbara in her home in Surrey, just outside London. Spent most of the time reminiscing with Barbara driving us around the picturesque Surrey countryside. Together with memorable meals in several old English Pubs. Much to the amusement of the other two, I always went for the Fish and Chips.

Following up in St. Lucia

There was every reason to believe that within this brief period CBR (Community Based Rehabilitation) had been well-established in St. Lucia. The country had plans to expand this programme.

One was able to reach the conclusion that the Manual had been an effective tool used by disabled people, their families and the Community Health Assistants. CHAs with a basic training of three months for their Primary Health Care work could with a further training of at least 12 days in a workshop situation and a further three weeks of field training and with regular and adequate support from a higher level carry out their rehabilitation tasks with disabled people successfully. The availability of second level support enhanced quality and coverage.

The Community Health Nursing Service or CHNS, recognising the value of the inputs from the two physiotherapists from the Victoria Hospital, intended to request the Ministry of Health for one of these therapists to be released to the CHNS. The CHNS was continuing its dialogue with the education sector to promote the inclusion of disabled children in local schools. They had started a conversation with employers regarding job opportunities for disabled youth and adults. And an information campaign to increase public participation in what was now a programme and no more a project.

I left St. Lucia confident that disabled people here had hope for the future.

Marcella Niles

But I cannot leave St. Lucia before including Marcella Niles in my story. The Community Health Nursing Service was her responsibility. As my counterpart she went everywhere with me. In Castries she drove me around herself in her own car. To go out of Castries we had access to a larger vehicle from the CHNS but often driven by Miss Niles herself. Marcella Niles was very proud of her island and quite rightly so.

She guided me to the most beautiful parts of St. Lucia. She would, whenever she could, take me through the town of Soufriere so that I could see the Pitons. And she always pointed them out to me – Big Piton and Small Piton, two tall volcanic spurs rising straight up from the sea, adjoining the coast. They were linked by some sort of a ridge.

On a few occasions when we had time to spare, she took me to see tropical rain forests which St. Lucia is well-known for. We in Sri Lanka have our own famous rain forest Sinharaja, which is a World Heritage Site. But these in St. Lucia were somehow different. Maybe had I gone deeper into our Sinharaja I would have found a similarity. In addition to the giant ferns and lush greenery, it was very, very wet all the time – as if a very slight rain was constantly falling. It was surprising that one could also see scrub forests in some parts of this small island.

For my stay in St. Lucia Marcella had found me accommodation in an Apartment Hotel, quite common in the Caribbean. This suited me well. It had a pool which none of the other residents appeared to use. So I had it to myself every evening after work.

After relaxing in the water, I would walk to the little shop at the bend in the road, not far down from me. There I would find something to cook for myself to eat with rice for the evening meal. May be some mixed vegetables or some fish. Whatever it was, it was tasty, cooked with St. Lucian curry powder. And always a luscious mango to follow. However good that mango was, it could not touch our delicious Jaffna mangoes for taste.

A Meeting in Sri Lanka

Before I move on from this phase of my journey in South America and the Caribbean, there was a meeting I must stop for. It was one I was called upon to organise – the WHO Interregional Consultation on CBR held in Colombo in June 1982.

WHO Interregional Consultation on CBR, 1982

It was almost three years since we had started work in the field. We felt the time was ripe to get the people who have been testing the Manual together to share experiences. Einar suggested that I organise the meeting in Colombo. Sri Lanka had also been participating in the field trial.

I was extremely fortunate and overjoyed to welcome to my own country so many friends I had made on my travels to their countries. Dr. Hindley-Smith asked for my help to organise a tour to places of historical interest and to the game parks. Others toured independently after the meeting was over. My country was, after all, a tourist attraction. And although I say it myself – it is beautiful.

When I had been in Jamaica, it had reminded me much of my own country. So much so that I had this in my thoughts. If ever, if ever I had to leave my motherland for some reason or another, I would settle down in Jamaica. That too was beautiful, particularly the northwest where I was, away from the tourist hot spot of Montego Bay. Not just the beaches and scenery, but more importantly, its people.

During our meeting Einar and Gunnel were guests in our home. This was not just enjoyable but also useful to have more time to spend in discussion and planning the next steps. For our meeting, 22 participants came together from all parts of the globe. Countries that had carried out field tests were Botswana, Burma, India (Kerala State), Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, St. Lucia and Sri Lanka. There were also others who were invited as representatives of WHO, other UN organisations and NGOs and some as individuals.

After an exchange of experiences from these countries, they spent much time giving their suggestions in detail as to what revisions should be made in the WHO Manual. These were taken into account when the Manual was revised the following year. CBR had been born.

Back to Asia – Malaysia

My First Contact with Malaysia

The first time I went to Malaysia was in 1983 to represent WHO at the Seventh Asia & Pacific Conference of Rehabilitation International, known globally as RI. It was founded in 1922 as an organisation that led discussion on issues related to disability at a global level. The climax of its work was a World Congress held every four years. On my stopover in Mexico, I referred to Dr. Hindley-Smith telling me about his participation at the RI Congress in Ireland in 1969. It brought about the realisation in him of the extent of neglect of disabled people in developing countries.

At that Congress, RI was promoting new thinking on personnel required for rehabilitation. It was looking at disability as a charity-based concept. In the 1980s it was promoting interventions for people with disability to improve their quality of life in a social context. Then, early in this millennium when the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities had been approved, their interest evolved to the promotion of disability rights.

Correspondingly, CBR had been accepted by the World Health Assembly. Increasingly now, more countries were adopting this approach both for policy and implementation. My own CBR story is about the small part I played travelling from country to country assisting them to start putting policy into practice. Just planting a seed as it were. How that seed would germinate and into what kind of tree it would grow was left to be seen. But germinate it did and by the time I got to Malaysia I was amazed at the way CBR was maturing.

It was blending with the particular ethos of each country to meet the needs of its disabled people.Seventh Asia & Pacific Conference of Rehabilitation International, Kuala Lumpur, 1983 RI (Rehabilitation International), the world body had some regional branches. Every two years RI organised a meeting in one of its regions. This first one I was invited to was in the Asia Pacific Region.

I was a speaker at a Plenary Session on the second day of the conference. The speaker before me was Dr. Siti Hasmah binti Haji Mohamad Ali, wife of the Prime Minister of Malaysia who we know as Mahathir Mohamed.

The topic of her presentation was a rather general one, focusing on the family as a vital provider of care. I had an opportunity of speaking with her in the break that followed the panel discussions. She told me her particular interest at that time was improvement in the situation of rural women.

That is why she had agreed to participate at this conference. She felt the discussion we had would help to promote her cause. I learned later that she and her husband had met at Medical School. They had been married soon after they left university.

I had been invited to present a paper on “CBR as a Relevant Approach for Developing Countries’. I included in the paper my thoughts on why a new approach was necessary with data from Sri Lanka. I also included a précis of the approach with examples, that WHO had adopted assisting countries to develop and of how it had impacted the quality of life of individuals and families; and a few results with statistical data from three countries – Botswana, Mexico and Sri Lanka, in three continents; and mention of its relationship to Primary Health Care, which at that time provided an entry point with the infrastructure.

My conclusions were that, “The results to date indicate emphatically that the approach is suited to the needs of developing countries… The quality of results cannot be questioned – for where better to provide freedom of mobility, create independence in daily life activities and enable disabled people to participate in the mainstream of community life than in the environment of their own communities?”

“The integration of disabled children in existing local schools and the provision of income generating opportunities within their own communities has ensured for disabled people full participation with true integration, starting with the family. It has done away with the need for them to be transported to a new and strange environment to be rehabilitated”.

Is CBR a Medical Model?

These results above are those that critics argued made CBR a “Medical Model” propagated by WHO. Some said this was because CBR was concerned also with functional independence. I say that maximal functional independence is an indication of an individual’s health status, beyond a medical condition. Improvement in the health of an individual is a human right. Besides, even an individual’s functional independence is not possible without social change in the community the individual lives in.

My own finding and therefore my argument was that participation in community life be it educational, functional or economic, cannot happen without a change in community attitudes. And with that an acceptance of disabled people on the basis of equality. An approach that was at this time being called “the Social Model”. CBR, based on the responsibility of the community, brought about a social change.

But I also saw CBR go beyond a purely social foundation; it also extended to enabling disabled people enjoy the same opportunities and responsibilities as others in their communities, an approach that is now called “the Human Rights Model”.

The world of disability did not use the words “human rights” at that time. But this was CBR’s needs-based approach, enabling equality in all matters including human rights. What is important is that CBR was not, for instance an individual-based, service-based approach reaching out from centres in districts or elsewhere. In these instances, responsibility lay with those centres, not with the communities in which disabled people lived.

Introducing CBR to Malaysia

It was against this background that the Government of Malaysia requested WHO cooperation to initiate CBR. In response, WHO sent me there for three months from February to May 1994. The mandate for matters related to disability lay with the Ministry of Social Welfare.

Initial discussions were with the Secretary of this Ministry. We talked about what he expected from me and about how I would set about the task he had set me. I said that WHO’s advice to countries was that the Manual, “Training in the Community for People with Disabilities”, be used as a tool for empowering disabled people and families with the knowledge and skills they required to start any change. I said without this tool for empowerment translated into Bahasa Malaysia CBR would be difficult for me to initiate in three months.

The Secretary called together ten members of his senior office staff. He removed the cord that held the different modules of the Manual together and separated the modules into ten lots. Giving one lot to each of his staff he said, “Could you please translate these and let me have them back by Monday?” Typed and photocopied, a sufficient number of Manuals were available to us when we required them. Such was the dynamism of this man who led the Ministry of Social Welfare at that time. I thought to myself, with this leadership anything should be possible.

So far, in other countries I had introduced CBR at the grass roots, promoting the development of a system upwards to support it. The structure for CBR was as yet incomplete in those countries, because appropriate mid-level personnel were lacking. This was a serious constraint for ensuring effectiveness as well as for sustainability.

Here in Malaysia for the first time, I was introducing CBR within a support system which had responsibility for disability – the Social Welfare Ministry. The Ministry had Social Welfare Assistants or SWAs at district level. To support them were Social Welfare Officers or SWOs at state level. Among them would be mid-level workers. They required relevant knowledge and skills in CBR. They required also to have this task included in their job descriptions. Then the focal points for a CBR system would be in place at the two support levels.

It would be up to officials at these levels to build the horizontal linkages within and outside government at each level that would together provide communities with the support they required. In development jargon this was called multi-sectoral collaboration. In reality, it sometimes worked in bits and pieces, often it did not. Much work was required here globally.

Local Accommodation

During the three months that I spent in Malaysia I was to work in Batu Rakit in the State of Terengganu on the east coast. Batu Rakit was a “Mukim” or sub district just over a half-hour drive from Kuala Terengganu, the capital of the state.

Our teaching area was rural. It was a quiet fishing village with the appearance of serenity and tranquillity. I was fortunate to be given accommodation here in a kind of rest house run by the state. This was a simple building set in a large property scattered with very tall coconut trees. There were a few rooms and some common bathrooms and toilets. The female participants from other states were accommodated in this rest house with me. Other participants found lodging in homes in the area. Evening meals to all were provided at the rest house. Because of this the group found much time to get to know each other and to talk about areas of common interest including work.

I liked very much the local food that was served. It was simple. “Nasi” means rice which is the staple in every meal. Here it was white rice served with Malaysian “curry”. Curries were in no way like ours, but this is what the dishes were called in English.

They were cooked with what we may call a raw curry powder – turmeric, coriander, cumin, cardamom, cloves, cinnamon and ginger, with such condiments added in different proportions. As a result of these particular condiments, the taste was subtle quite unlike ours which tends to be spicy, even our white curries.

The rice was served with many different vegetables, and always fish from the village. My favourite Malaysian dish was nasi dagang. For special Malaysian dishes such as these, the rice is cooked in coconut milk, and it turns out rather like our milk rice or “kiributh”. Except that it is flavoured with pandan leaf or “rampe”.

The tastiest nasi dagang I had was served in the Hotel in Kuala Terengganu where I stayed for a few days before moving to Batu Rakit. It was served with fried sprats, shrimp sambol, a boiled egg and cucumber. What we eat as nasi lemak in Colombo or even the food in Kuala Lumpur is nothing like the Malaysian food I ate in Kuala Terengganu. There, food was very tasty with the subtle flavours of the food itself.

In Colombo I now eat Malaysian food with a rather spicy chicken curry, adapted to suit the local palate. In all my later visits to Kuala Lumpur staying in international hotels as I did, I was not able to find the original Malaysian food that I had enjoyed in the rest house in Batu Rakit.

Features

Are we witnessing end of globalisation? What’s at stake for Sri Lanka?

Globalisation can be understood as relations between countries, and it fosters a greater relationship between countries that involve the movement of goods, services, information, technology, money, and human beings between countries. These relationships transcend economic, cultural, political, and social contexts.

Globalisation in the modern world today is a significant shift from the past. Globalisation in the modern world today is a state in which the world becomes interconnected and interdependent. This change occurs due to better technology, transport, communication, and foreign trade.

Trade routes have joined areas for centuries. The Silk Road and colonial sea trade routes are the best examples. But today, nobody can match the speed and scope of globalization.

Globalisation began to modernise after World War II. During this time, countries came to understand that they had to work together. They wanted to have economic cooperation and peace so that they would not fight any more. These significant institutions united countries for political and economic purposes and advantages. They allow free movement of products, services, and capital between countries. It encourages cooperation all over the world.

The second half of the 20th century saw fabulous technological advances. These advances sped up globalisation. The internet changed everything. It changed the way people communicate, share information, and do business. Traveling became faster and more efficient. Products and humans travel from one continent to another in record time. Companies can now do business globally. They outsource jobs, get access to global markets, and use global supply chains. This was the dawn of multinational firms and a global economy.

Flow of information is one of the characteristic features of the current age of globalisation. The internet allows news, ideas, and culture to be shared in real-time. Societies are experiencing unprecedented cultural interconnectedness. This has led to controversy over cultural sameness and dissimilation of local cultures. For example, the same is observed within countries too. In countries such as Sri Lanka the language differences between districts have become a non-issue, and the western province’s language has paved the way for others to emulate. Globalisation has allowed millions of individuals to lift themselves out of poverty, especially in Asia and Latin America. It does this by creating new employment opportunities and expanding markets. It has also increased economic inequalities, though. Wealth flows to those who possess technology and capital. Poor workers and communities are unable to compete regionally or internationally. Some countries have seen political backlash. In these countries, some people feel left behind by the benefits of globalisation.

Modern globalisation has a lot to do with environmental concerns. More production, transportation, and consumption have destroyed the planet. These are pollution, deforestation, and climate change. Global issues need global solutions. That is why international cooperation is essential in solving environmental problems. The Paris Climate Agreement is one such international effort to cooperate. There are constant debates regarding justice and responsibility between poor and rich countries.

Modern-day globalisation deeply influences our daily lives in many ways. It has opened up possibilities for economic growth, innovation, and cultural exchange. However, it also carries with it dire consequences like inequality, environmental destruction, and displacement of culture. The future of globalisation will be determined by the way we handle its impact. We have to see to it that its benefits are distributed evenly across all societies.

Tariffs are globalising-era import taxes. Governments levy them to protect domestic firms from foreign competition. But employed ruthlessly and as retaliation like today, and they can trigger trade wars. Such battles, especially between big economies such as the U.S. and China, can skew trade. They can destabilise markets and challenge the new era of globalisation. Tariff wars will slow or shift globalisation but won’t bury it.

Globalisation is not just a product of dismantling trade barriers. It is the product of enormous forces like technology, communications, and economic integration in markets across the globe. Tariffs can limit trade between countries or markets. They cannot undo the fact that most economies in the world today are interdependent. Firms, consumers, and governments depend on coordination across borders. They collaborate on energy, finance, manufacturing, and information technologies.

However, the effects of tariff wars should not be downplayed. Excessive tariffs among dominant nations compromise international supply chains. This also raises the cost for consumers and creates uncertainty for investors. The 2018 U.S.–China trade war created billions of dollars’ worth of tariffs. It also lowered the two countries’ trade. Industries such as agriculture, electronics, and automotive manufacturing lost money. These wars can harm international trade confidence. They also discourage higher economic integration.

There are some nations that are facing challenges. They are, therefore, diversifying trade blocs. Others are creating domestic industries. Some are also shifting to regional economic blocks. This may result in more fragmented globalisation. Global supply chains can become short and local. The COVID-19 pandemic and tariff tensions forced countries to re-examine the use of foreign suppliers. They began to stress self-sufficiency in vital sectors. These are medicine, technology, and food production.

Despite these trends, globalisation is not robust. The global economy can withstand crises. It does so due to innovation, new trade relations, and digitalisation. E-commerce, teleworking, and online communication link people and businesses across the globe. Sometimes these links are even stronger than before. Countries need to come together in order to combat challenges like climate change, pandemics, and cybersecurity. This is happening even as economic tensions rise.

Tariff wars can disrupt trade and create tensions.

However, they will not be likely to end globalisation, but instead, they reshape it. They might change its structure, create new partnerships, and help countries find a balance between openness and security. The globalization forces are strong and complex. They can be slowed down or reorganized, but not readily undone. The future of globalisation will depend on how countries strike their economic interests. They must also recognise their interdependence on each other in our globalised world. The world economy has a tendency to change during crises.

It does this through innovating, policy reform, building strong institutions, and changing economic behavior. But they also stimulate innovative and pragmatic responses by governments, companies, and citizens. The world economy has shown that it can heal, change, and change after crises like financial downturns, pandemics, and geo-political conflicts. One of the more notable examples of economic adjustment occurred in the 2008 global financial crisis. The crisis started when the housing market in the U.S. collapsed. The big banks collapsed, and then the effects spilled over to the world. This led to recessions, very high unemployment levels, and a drop in consumer confidence. In response, central banks like the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank acted very quickly. They cut interest rates to near zero. They also started large-scale quantitative easing. Governments spent stimulus money in their economies. They assisted in bailing out banks and introduced tax-tight financial regulations. These actions stabilised markets and ultimately restored economic growth. The crisis also led to new financial watchdog mechanisms. One example is the Financial Stability Board, which has the objective of avoiding such collapses in the future. The COVID-19 pandemic created a unique crisis.

It reached health systems and economies globally. In 2020, the world suddenly stopped. Lockdowns and supply chain disruptions followed. This led to a sharp fall in GDP in almost all countries. Sri Lanka experienced it acutely. However, the world economy has adapted at a breathtaking speed. Remote work and online shopping flourished, driven by digital technology. Firms transitioned to new formats like contactless offerings, delivery platforms, and remote platforms. Governments rolled out massive stimulus packages to businesses and employees. Central banks infused liquidity to support financial systems. International cooperation on vaccine development and distribution also helped accelerate economic recovery. By 2021 and 2022, various economies were quicker to recover than expected, though unevenly by region. Another outstanding one is the manner in which economies adapted to geostrategic struggles:

The war of 2022 between Ukraine and Russia ravaged across world markets of food and energy, with special impact on Europe and the Global South.

European nations moved swiftly to abandon Russian natural gas. European nations also looked around for other sources of energy and increased usage of renewables. While shock caused inflation as well as supply shortages to a peak first, markets began to shift ultimately. And world grain markets looked elsewhere and established new channels of commerce. Such changes show the ways that economies can change under stress, even if ancient structures are upended. Climate change is demanding long-term change in the world economy.

The climate crisis isn’t a sudden crisis, like war or pandemic. But it’s pushing nations and businesses to make big changes. Green technologies are on the rise. Electric vehicles, solar and wind power, and carbon capture are the best examples. These technologies are indicative of how economies address environment crises. Financial institutions and banks are now embracing sustainable investing guidelines. Countries are uniting in a low-carbon future under the terms of the Paris Climate Accord. Technology is leading economic resilience.

The digital economy is going stratospheric—AI, cloud computing, and e-commerce are the jetpack! These technologies enable companies to be agile and resilient. Consider the pandemic and the financial crisis, for instance. Technology businesses did not just survive; they flew like eagles. They gave us remote work tools, digital payments, and virtual conversations, allowing us to stay connected when it was most important. These innovations have irreversibly shifted the terrain of worldwide business and work. The global economy’s history is marked by crises and its capacity to adapt and transform in response. The global economy proves strong during financial crises, pandemics, conflicts, and climate issues. Resilience shines through innovation, teamwork, and strategic adjustments. Though challenges linger and vulnerabilities remain, we’re not without hope.

Learning from crises helps us fortify and adapt our systems. This adaptability signals a promising evolution for the global economy amid future uncertainties.

The current trade war, especially between the United States and China, is reshaping globalization. It may lead to a new form of it. These tensions do not terminate globalization. Instead, they push it to evolve into a more complex and regional form. The new model includes economic factors. It also includes political, technological, and security factors. This leads to a world that remains interconnected but in more cautious, selective, and fragmented ways.

Trade wars tend to begin when countries want to protect their industries.

They might want to lower trade deficits. They also respond to unfairness, including intellectual property theft or state subsidies. The ongoing trade war between China and the U.S. has seen massive tariffs, export quotas, and increasing geopolitical tensions. This is a sharp departure from the post-Cold War era, which saw more free and open trade. Now, companies and governments prepare for everything. Safety and national interests are their concerns. This change is reflective of a trend that some experts call “de-risking” or “strategic decoupling.” One of the most obvious signs of this new course is the reorganization of global supply chains.

Many global companies want to diversify away from relying on one country. They especially want to decouple from China for manufacturing and raw materials. They diversify production by investing in different regions. It is called “China plus one.” It means relocating operations to locations like Vietnam, India, and Mexico. This relocation takes global supply chains from centralized to more regionalized and redundant networks. These networks prepare for future shocks. Moreover, technology and digital infrastructure have an increasing role in this new globalization.

Trade tensions are an indication of the strategic value of semiconductors, telecommunications, and artificial intelligence. Nations are realizing that technology is a national security issue. Therefore, they have invested in their local capabilities and restricted foreign technologies’ access. The U.S., for example, has put export restrictions on high-end microchips and blocked some Chinese technology companies from accessing its market. China and other nations have increased efforts in developing independent ecosystems for technologies. This has given rise to parallel technology realms. This could result in a “bifurcated” global economy with different standards and systems. The current trade war is also strengthening the advent of regional trading blocs.

Global trade agencies like the World Trade Organization are getting weakened. This is owing to the fact that the world’s major nations are competing with one another. Hence, the nations are currently opting for regional agreements to develop economic cooperation. Discuss the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in Asia. And let’s not forget the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA). Collectively, these agreements represent a new era of globalization. It’s no longer a free-for-all; rather, it’s a strategic web spun with trusted partners and regional ambitions resulting in ‘islands’ or ‘regions’ of globalization. The new model of globalization creates greater independence and security for some but presents issues.

The countries that previously prospered from the exportation of goods and involvement in the global market may face greater challenges. As protectionism rises and competition becomes greater, customers may pay more. Economic inefficiencies are a likely reason. Additionally, the disintegration of international institutions may stop countries from agreeing on important issues. Problems like global warming, pandemics, and economic downturns can become harder to resolve. The current trade war will not end globalization, but it is reshaping it. We see a new type of globalization that is fragmented, regional, and strategic in character. Countries are still interdependent, but such economic dependency is underpinned by trust, security, and competition. Globalization is changing, so we must balance these changes with the imperatives of cooperation in our globalized world.

New types of globalization include regional trade blocs, reshaping supply chains, tech decoupling, and growing geopolitical tensions.

For Sri Lanka, the changes have far-reaching consequences.

Being a small nation strategically located, Sri Lanka relies on trade, tourism, and foreign investment. Globalization is, however, more fragmented and politicized and security-oriented. This offers opportunities and challenges for Sri Lanka. To survive, the country must reform its economic policies. It must diversify relationships and maneuver the rival interests of global powers with caution.

One of the most immediate effects of the new globalization is realigning global supply chains.

Multinationals want to wean themselves from China. They want to shift production elsewhere. Sri Lanka can be a new hub for light manufacturing, logistics, and services. Being located on key shipping routes in the Indian Ocean means that it is a vital node in global ocean trade. Sri Lanka can lure more foreign investment by improving its infrastructure, bolstering digital strength, and upgrading the regulations. This would help firms to open up business. This would create employment as well as improve export-led growth. But the shift towards regionalism in global trade also poses danger.

The rest of the countries outside these alignments might be left out as major economies create closed trading blocs. Examples include the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and bilateral agreements like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. Sri Lanka is not part of most of the world’s biggest trade blocs, limiting its access to large markets and preferential trade conditions. Exclusion could make exports less competitive. It could also reduce the nation’s appeal as an international production base. To fulfill this, Sri Lanka must pursue trade agreements with regional powers like India and ASEAN nations in order to keep up with shifting trade networks. One key feature of the new era of globalization is a focus on ‘technological sovereignty’.

This includes the rise of alternative digital ecosystems, especially between China and the US. Sri Lanka must manage the tech divide wisely. Countries are closing doors to other people’s technologies and creating their own networks. Cyber security, digital infrastructure, and data governance require investments. Sri Lanka also needs to balance embracing new technology while preserving its digital sovereignty. Dependence on technology from a single country could yield dangers, as digital tools will be the main movers in the realms of governance, finance, and communication. Geopolitical competition, especially in the Indo-Pacific, also affects Sri Lanka’s economic and strategic location.

The island’s location has drawn China and India and Western nations. China’s involvement in Sri Lankan infrastructure projects, such as the Hambantota Port and the Colombo Port City, has yielded economic advantage as well as concerns regarding debt dependence and strategic control. Meanwhile, India and its allies have expressed interest in balancing Chinese power in the region. This is a sensitive balance that Sri Lanka has to exercise strategic diplomacy to reap foreign investment without being entangled in great power rivalry or compromising sovereignty. In addition, economic resilience in the face of global shocks—such as the COVID-19 pandemic, energy shocks, and food crises—has emerged as a top priority in the new era of globalization.

The recent economic slump in Sri Lanka, marked by a sovereign default, foreign exchange crises, and inflation, underscored the country’s vulnerability to global shocks. These events underscore the need for greater economic diversification, sound fiscal management, and long-term development. Sri Lanka must build stronger domestic industries, shift to clean energies, and transform regional supply systems that are less vulnerable to shocks from the outside. Generally speaking, therefore, the new patterns of globalization present Sri Lanka with a risk-laden world of possibility too.

While transforming global patterns of trade and investments creates new doors to economic growth, it steers the country towards more aggressive competition, geopolitical tensions, and internal vulnerabilities. To thrive in this fast-evolving world, Sri Lanka must adopt an assertive strategy of regional integration, technological resilience, strategic diplomacy, and inclusive economic reform. On the way, it can transform foreign uncertainty into a platform for sustainable and sovereign development.

by Professor Amarasiri de Silva

Features

Fever in children

by Dr B.J.C.Perera

by Dr B.J.C.Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey),

DCH(Eng), MD(Paed), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK),

FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health Section Editor, Ceylon Medical Journal

Fever is a common symptom of a variety of diseases in children. At the outset, it is very important to clearly understand that it is only a symptom and not a disease in its own right. When the body temperature is elevated above the normal level of around 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit (F) or 37 degrees Celsius (C), the condition is referred to as fever. It is a significant accompanying symptom of a plethora of childhood diseases. All children would get a fever at some time or another in their lives, and in the vast majority of cases, this is due to rather mild illnesses, and they are completely back to normal within a few days. Some may have a rather low-grade fever, while others may have quite a high fever. However, in certain situations, fever may be an important indication of an underlying serious problem. The significance depends entirely on the circumstances under which this occurrence is seen.

Irrespective of the actual underlying reason for the fever, the basic mechanism of causation of fever is the temporary resetting of the temperature-regulating thermostat of the brain to a higher level. The consequences are that the heat generated within the body is not effectively dissipated. It is merely a body response to a harmful agent and is a very important defence mechanism. Turning up the core temperature is the body’s way of fighting the germs that cause infections and making the body a less comfortable place for them. However, less commonly, it is also a manifestation of other inflammatory disorders in children. The significance of fever in such situations is a little bit different to that which is seen as a response to an infection.

The part of the human brain that controls body temperature is not fully developed in young children. This means that a child’s temperature may rise and fall very quickly and the child is also more sensitive to the temperature of his or her surroundings. Although parents often worry and get terribly scared with the child developing fever, it does not cause any harm by itself. It is a good thing in the sense that it is often the body’s way of fighting off infection.

It is quite important to note that the actual level of the temperature is not always a good guide to how ill the child is. A simple cold or other viral infection can sometimes cause a high fever in the region of 102 to 104 degrees Fahrenheit or 39 to 40 degrees Celsius. However, this does not always indicate a serious problem. It is also true to say that some more sinister infections could sometimes cause a much lower rise in the body temperature. Because fevers may rise and fall, a child with a fever might experience chills and shivering as the body tries to generate additional heat as the body temperature begins to rise. This may be followed by sweating as the body releases extra heat when the temperature starts to drop. Children with fever often breathe faster than usual and generally have a higher heart rate. However, fever accompanied by obvious difficulties in breathing, especially if the breathing problems persist even at times the temperature is normal is of significance and requires urgent medical evaluation of the situation. Generally, in the case of children, the way they act is far more important than the reading on the thermometer, and most of the time, the exact level of a child’s temperature is not particularly important, unless it is persistently very high.

Although many fevers need just simple remedies, under certain conditions the symptom of fever needs rather urgent medical attention. This is the case in babies younger than three months. Same is true even in a bigger child if the fever is accompanied by uncontrollable crying or pain in the neck with a severe headache. Marked coughing and or difficulty in breathing coupled with fever needs to be medically sorted out. Fever combined with pain and difficulty in passing urine, significant tummy pains or marked vomiting and diarrhoea too would need medical attention. Reddish rashes and bluish spots on the skin with fever also need to be seen by a doctor. The illness is probably not serious if a child with a history of fever is still interested in playing, is eating and drinking well, is alert and smiling, has a normal skin colour and looks well when his or her temperature comes down. However, even with rather low levels of fever, under certain conditions, medical attention should be sought. In situations such as when the child seems to be too ill to eat and drink, has persistent vomiting or diarrhoea, has signs of dehydration, has specific complaints like a sore throat or an earache or when fever is complicated by some other chronic illness, it is prudent for him or her to be seen by a qualified doctor.

One could take several steps to bring down a fever. It is very useful to remove most of the clothes and keep under a fan to facilitate heat loss from the body. If there is no fan available, one could try fanning with a newspaper. A very effective way of bringing down a temperature is to sponge the body with a towel soaked in water. The water must be at room temperature or a bit higher. One should not use ice or iced water on the body. Ice will lead to contraction of the blood vessels of the skin and the purpose would be lost as more heat will be conserved within the body. There is no evidence that ice on the head helps to bring down the fever or to prevent a convulsion. If a medicine is to be used, paracetamol is probably as good as any other drug, but the correct dosage according to the instructions on the container should be used for optimal benefit. The best way of calculating the appropriate dose is by using the body weight. It is very important to stress that aspirin and aspirin-containing medications should not be used in children, merely to bring down a fever.

A child with fever loses a considerable amount of fluid from the body, particularly due to sweating. It is beneficial to ensure that the child drinks plenty of fluids. A good index of the adequacy of fluid intake is the passing of normal amounts of urine. A reduced solid food intake would not matter that much just for a couple of days of fever, but in prolonged fevers adequate nutrition too becomes quite important. A child with a high temperature also needs rest and sleep. They do not have to be in bed all day if they feel like playing, but they must have the opportunity to lie down. Sick children are often tired and bad-tempered. They sleep a lot, and when they are awake, they want their parents around all the time. Perhaps it is quite useful to spoil them a little bit when they are ill and to read to them, play with them or just spend time with them. It is best to keep a child with a fever home and not send him or her to school or child care. Most doctors would agree that in simple fevers, it is quite satisfactory for the child to return to school or child care when the temperature has been normal for over 24 hours.

Trying to get the temperature down would make the child more comfortable. However, it is not essential to get it down to normal and to keep it there scrupulously. Parents often worry that either the fever simply refuses to abate or springs up again after a couple of hours. It must be realised that certain fevers have to run their course and will not come down to normal in a hurry, despite whatever measures that are undertaken. This is particularly true of viral fevers. Some parents are terribly worried at the slightest elevation of the temperature and go running to doctors looking for a “magic cure” for the fever. Many fevers do not need urgent medical attention and one could watch it for a few days and see how it progresses. Yet for all that, if there are some worrying signs then it is advisable to seek advice from a qualified doctor.

It is a familiar occurrence that many people believe that a high fever is quite dangerous. Fever by itself has no major long-lasting effects. If one appreciates that high fever is just a symptom and that it is only a reaction of the body to something untoward going on, then it is easy to consider it to be just like any other symptom of a disease. Some are also under the misconception that a high fever could cause a convulsion. This is not always the case, and a convulsion would occur only in those children who have the constitutional tendency to get them. Convulsions are not always related to high fever, and in those who are susceptible, even moderate and sometimes mild fever could trigger a convulsion. High fever does not lead to lasting brain damage in its own right either. Fever is sometimes an indication of a significant infection, but in those circumstances, the primary disease itself is the real problem. In situations where medical help is desirable, what is most important is the way a fever is sorted out and some kind of a diagnosis being made as to the real cause of the fever. The crucial component of the treatment of a fever caused by an underlying problem is the treatment of the root cause.

Features

Robbers and Wreckers

To quarrel with them is a loss of face

To have their friendship is a sad disgrace

Those lines by Bharavi were written after the fourth century A.D. when Sanskrit was already a purely literary language.

We have had the spectacle of a reporter in DC asking Donald Trump whether he regrets his lying all the time every day of his life. And, Trump responded “What did you say?” and one could see that such a possibility had never occurred to him: he was genuinely baffled.

The question here and now is whether such a thought has ever come to Anura Kumara Dissanayake and Harini Amarasuriya, both obedient servants of the US and India. For example, the prathigna given by Amarasuriya as she was sworn in by AKD as Prime Minister in a Cabinet of three. That their doings are in line with the desires of Ranil Wickremesinghe (and maybe the “aspirations” of their buddies) would translate also to the cover up of his bringing in Arjuna Mahendran, the son of a Chairman of the UNP, to trash the Central Bank and execute Ranil’s bond scam.

In the matters of managing our economy and respecting our age-old culture this lot have shown us glimpses of the lunatic self-applause that define Trump’s doings. As phrased by a commentator in the U K Guardian a few days ago Trump’s endeavours “weren’t about Making America Wealthy Again. This was much more primal. Sticking it to all the people who had laughed at him over the years. His bankruptcies. His hair. His orangeness. His stupidity. Sticking it to all those who had taken him to court and won. Now he was the most powerful person in the world. He had the whole world watching as he messed it up. He could do what he liked.”. It’s quite obvious that the last is how AKD, HA, Yapa and the top tier of those most culpable have read their horoscopes: they do not expect to be held accountable

“The U.S.’s new tariff policy reflects a broader shift away from globalisation and towards economic nationalism and national balance sheet economic model approach”. So wrote a self-styled Business Cycle Economist last week. That is the kind of delusion that ‘growth-friendly’ market theory such ‘economists’ are trained to shove down the throats of politicians possessed of just about the bit of wit required to enrich themselves in tandem with the IMF and those entrepreneurs it supports.

At this point we should note also that Trump’s new wave of tariffs was harshest on Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam and Sri Lanka––all, coincidentally, in addition to their strategic importance for war-mongers, Buddhist countries.

How closely those who call the shots among the power-wielders here follow Trump is seen in their response or lack of one to the earthquake that has devastated Myanmar and Thailand a week ago. The USA has been salivating over the riches of Myanmar for a long time, confident that Aung Suu Kyi would deliver them on a platter. That no doubt was the object of the aragalaya here and seems within reach for India now.

For months now, from 2022 at least, there have been markers that showed who was running the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (so calling themselves) and what their agenda was with respect to our country and her people. An early eruption that showed their hand was that aragalaya‘. It was designed to ensure a regime change that would place, let us for convenience say, Adani in charge. It involved, as a first step, getting Gotabhaya out of the presidency. That it was so was also shown two years ago in the London Review of Books by Pankaj Misra in an essay titled “The BIG CON” on Modi’s India. In which Gotabhaya and Adani are mentioned and the above object specified.

Misra’s latest work has been on “The World After Gaza” – a reference not without its applications not only to Modi’s support for Adani in Haifa, but to the ridiculous and altogether culpable gestures of friendship towards the US-Israeli led coalition of criminals shown by Ranil Wickremasinghe and associated Colombians who succeeded him. Haifa is the largest port in that segment of occupied Palestine and the Trump group also has had a stake in it.

I shall pause here with the concluding lines of Bharavi’s quatrain.

One of sterling judgment realizes

What fools are worth and foolish ones despises.

by Gamini Seneviratne

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoColombo Coffee wins coveted management awards

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDaraz Sri Lanka ushers in the New Year with 4.4 Avurudu Wasi Pro Max – Sri Lanka’s biggest online Avurudu sale

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoStarlink in the Global South

-

Business6 days ago

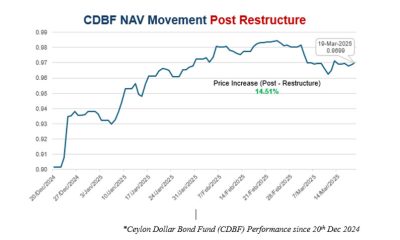

Business6 days agoNew SL Sovereign Bonds win foreign investor confidence

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoSri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part III

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoModi’s Sri Lanka Sojourn

-

Midweek Review2 days ago

Midweek Review2 days agoInequality is killing the Middle Class

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoSri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part I