Features

Educational Experience in the COVID19 era : Challenges to Opportunities

Senior Professor Chandrika N Wijeyaratne

MBBS (Colombo), MD (Colombo), DM (Colombo), FRCP (London),Vice-Chancellor, University of Colombo

I am deeply humbled and greatly privileged to deliver the 2021 memorial lecture to honour Professor J.E. Jayasuriya – a pioneer educationist, academic and a brilliant son of Sri Lanka.

Born on February 14, 1918, he received his education in three schools ending with Wesley College, Colombo. Having excelled at the Cambridge Senior Examination and being placed third in the British Empire he was awarded a scholarship to the University College Colombo from where he obtained a First Class in Mathematics.

He was the first principal of Dharmapala Vidyalaya, Pannipitiya and forsook a career in the coveted civil administrative service due to his resolute stand on encouraging Buddhist schools. He was handpicked by the father of free education and then minister of education, Dr. C.W.W. Kannangara, to lead the central school established in his own electorate of Matugama.

Following Postgraduate studies at University of London he was placed in charge of Mathematics education at the Teachers’ College Maharagama until being appointed as a lecturer in the Department of Education of the University of Ceylon. In 1957, he succeeded Prof. T.L Green as Professor of Education, with the singular distinction of being the first Sri Lankan to hold this post.

In his capacity as Professor and the Head of Department, Prof. Jayasuriya undertook the task of professionalizing education. He was a role model to the academia with his professionalism, erudite outlook, integrity and a deep commitment to his chosen field.. It was his vision that paved the way for the first undergraduate degree- Bachelor of Education awarded by University of Peradeniya in the nineteen sixties. The majority of the first generation of B.Ed. graduates achieved high professional status both locally and globally. The popularity of this course, which is now offered at the University of Colombo, testifies the foresight of Prof. Jayasuriya in developing this programme. While there are moves to expand today’s Bachelor of Education programmes, it is necessary to review these programmes in the light of Prof. Jayasuriya’s vision to maintain the quality of the very study course he designed.

I am captivated by Professor J. E Jaysuriya’s close association with medical education. He assisted Professor Senaka Bibile to establish the Medical Education Unit at Peradeniya. He delivered several guest lectures on measurement techniques and psychometry. He was elected as a Chartered Psychologist (U.K.) having the right to practice as a Psychologist. in the U, K. Later he was the UNESCO Regional Adviser on Population Education in Asia and the Pacific and one of his articles on the ‘Inclusion of Population Education in the Medical School Curriculum’ was ublished in the British Journal of Medical Education.

Educating the educators of Sri Lanka has now become a norm in Sri Lanka, about which Prof Jayasuriya would be extremely proud. The distinct features of Prof Jayasuriya’s approach to education, based on the information I gathered about him, include his distinctive approach to psychology and mathematics, intelligence testing and educational policy with a holistic, practical and pragmatic outlook; that I propose modern-day educationists should emulate. May his memory remain etched in the education landscape of mother Lanka!

Preamble

Sri Lanka has remained unique in its obligation to universal education over the past seven decades, well before more advanced countries gave due consideration to this aspect of social development. Despite multiple challenges faced, we have safeguarded education as a sacred and quintessential commodity.

The infrastructure, human resource and facilities for education have remained a priority in the eyes of the general public. Nevertheless, there are many unmet needs of tertiary education in Sri Lanka that caused concern for whole of society over the last two decades. It is noteworthy that University Grant Commission (UGC) statistics show that only six percent of young adults (between 18 and 24 years) are enrolled in state universities, while another five percent are enrolled in other state higher educational institutions. A further six percent are enrolled in non-state higher educational institutes with an additional three percent enrolling for external degree programmes. In total, the Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) for tertiary education in Sri Lanka is only approximately 20%, being the lowest among all middle-income countries and below the average value of 24% for South Asia.

Furthermore, Sri Lanka has one of the highest rates of brain drain in South Asia. The World Bank figure for migration stands at 27.5% among those who received tertiary education, with an average annual migration level of 6,000 professionals. I consider this to be an underestimate by not factoring in the youth migrating for tertiary education while draining our foreign exchange.

The vision statement of the incumbent head of state, His Excellency President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, elucidated the need to introduce a reformed education policy and aim for no student who is suitably qualified to be deprived of higher education.

While discussion and deliberations were in progress on how this transformation must be addressed, the country faced the first wave of the COVID19 pandemic and a shutdown of all education institutions by mid-March 2020. The Presidential Task Force (PTF) on Sri Lanka’s Education Affairs was established through a gazette notification on March 31, 2020. The PTF which consisted of experts in the fields of education and higher education, was initially formed into three (03) Core Groups to propose suitable recommendations in the education sectors of General Education, Higher Education and Vocational Education. This was probably the first attempt to address education holistically under one umbrella and as a lifelong need. The TF was required to explore differences and variation of students, institutions and available resources.

COVID19 pandemic – the basis for the response of Higher Education Institutes

The single purpose required from us was to ensure there was no shutdown of education and to optimize the conversion of the process to online learning. Undoubtedly, adult education was the main sector deemed appropriate for an overnight transformation to the Online Distance Education (ODL) format.

With regard to long-term educational reforms beyond Covid-19 and the national expectations for broadening opportunities in tertiary education, far-reaching changes were required. The PTF recognized the need to transform the current tertiary education sector in Sri Lanka to become a globally recognized tri-partite system that consists of three key types of higher educational institutions (HEIs), namely,

1) State and Non-state Undergraduate HEIs

2) Postgraduate Research Universities, and

3) State and Non-state Vocational and Professional Institutions

This transformation was proposed with the explicit purpose to improve access to tertiary education, provide more flexibility and mobility within and among the three tiers and sectors, offer diverse opportunities for education, training and career paths, enhance standards, quality and relevance of training and promote postgraduate education, with particular emphasis on research, innovation and commercialization; all of which can upscale the economy and national development.

In terms of the required immediate change over to the digital mode, let us recollect the Sri Lankan State Sector experience with ODL by early 2020, immediately preceding the COVID19 pandemic. The Open University of Sri Lanka (OUSL), with a student population of 40,000, had the longest experience with ODL spanning 40 years. Online teaching commenced at the OUSL in 2003, with 50% of the courses made available online. This facility was provided as Supplementary, Blended and as an Online Plus. The open university included formative assessments as assignments, quizzes and discussion forums in the blended online courses. Limited summative assessments (final examinations) were conducted online, under a supervised environment in the computer laboratories of the Regional Centers of the OUSL.

An open-sourced support such as Moodle for the LMS, cloud based digital infra-structure and sustained interaction with LEARN, provided the necessary pathway to achieving the digital transformation.

Indeed, our IT experts provided speedy and unstinted support at the request of the UGC, with our own director of the University of Colombo School of Computing (UCSC) being a great pillar of strength. Permit me to divert here and share with you how this very personality, Prof KP Hewagamage the incumbent director of UCSC, recalls with gratitude how Prof J E Jayasuriya’s book on ‘Veeja Ganithaya’ for schoolchildren captivated his attention and was a life changing experience to learn mathematics from grade six in school! Free access to internet connection via LEARN was negotiated with service providers by HE the President, that ensured that the economically disadvantaged segments of our university population were not left behind. Nevertheless, many of our students still do not own a device to access online and/or have adequate internet bandwidth in their homes to effectively use the LMS. Smart phones were the first best option to ensure a timely transition – and was our only choice.

The concept of a virtual campus through the OUSL system that provides free internet access to students via computer laboratories based in Regional and Study Centers situated in every district was re-visited. Ensuring the provision of a Tablet PC to every student was recognized as priority, so that the new entrants in 2020/2021 are to be provided with student loans for this purpose.

Student centered independent learning was propelled into action. Despite many challenges, this transformation of the educational process would be viewed by the late Professor Jayasuriya as a veritable liberation from a stifled system, that was the main reason for the broader vision to transform education. Without doubt, Sri Lanka was entrapped in a tuition-based examination-oriented rote learning ethos, from which we clearly require to disengage. The COVID19 related shift in demand of educational lifestyle was the ideal opportunity for the deliverance of a more fulfilling and productive educational process and outlook for 21st Century Sri Lanka.

Learning Resources for

Online Education

Quality learning resources are vital for the success of online learning. In this context, internationally recognized free and open educational resources are available in the cyberspace free of charge.

It is noteworthy that the Government of India supports the most disadvantaged through an indigenously developed IT platform. Highly ranked Indian universities provide courses on the distance mode through SWAYAM (Study Webs of Active Learning for Young Aspiring Minds) and share quality teaching learning resources for Indian nationals anywhere, at any time.

Learner Support

A distance learner should have plenty of self-motivation. A web conferencing system through which the teachers make regular contacts, both synchronously and asynchronously, enables access for students located in remote locations. As per the OUSL experience, effective learner support is achieved by offering multi-device/ multi-mode learning opportunities to meet the learning needs of a mixed student population.

The COVID 19 pandemic impacted severely on our educational processes and systems. Permit me to share with you my experience in this transition as the administrative and academic lead of the University of Colombo, the pioneer institution of modern tertiary education in Sri Lanka. I consider this experience personifies how challenges imposed by the pandemic were transformed into opportunities.

The need for a flexible attitude to the learning and teaching process is of paramount importance to achieve any success with ODL. I am proud to say that a wider sector of our own staff encouraged their students to engage in home gardening; with a view to augmenting psycho-social adjustment to the sudden transition to home-based education, loss of peer group interaction and encouraged students to support their family economy through agriculture. Nevertheless, tilling the land fell far short of the dignity of university education! Acquisition of skills from hands-on laboratory and clinical settings in parallel with the development of leadership, teamwork, soft skills, sports and recreation were clearly not possible with ODL.

We received baseline information on the major issues faced by the students following relocation in their own homes. The impact had socio-economic and gender sensitive dimensions that required intensive support. Thus, the COVID19 threat of a pandemic brought into focus many unmet needs of the modern-day university student; ranging from the need for self-employment opportunities to sustain student education to their individual preferences for city-based versus. rural living. The wider community of the student groups suffered a major anxiety, with the haunting question – when can we graduate? Thereby, every faculty and institute along with the Sripalee campus and the school of computing, were able to effectively create and maintain channels of communication by linking the students with the central administrative process, in order to ensure a coordinated process for the provision of optimum support. I take pride in recounting this staff and alumni support for students that I believe made a meaningful impact on the personality development of our student population.

Our university, in parallel, was catalyzed into a new work norm – of a digital transformation in our educational activities. Online meetings became standard daily practice to manage the University administration. We took pride on becoming paperless, with the formalizing of an online document management system, with the official use of e-signatures and digital certification which resulted in improved efficiency, transparency and flexibility. The benefits of work from home, adopting healthy practices in the working environment, promotion of innovation to address social needs, with a fair share of the responsibility falling upon university systems were positive developments from the Covid-19 pandemic, that should be harnessed for future implementation.

I reiterate that our staff was very supportive to support the new model of ODL; often taking on re-orienting and re-learning while coping with the additional workload. Traditional wisdom and foresight enabled us to think positively and respond pragmatically. We had a few doubting Thomas’s, but such negative thoughts were considerably mitigated by an overwhelming ethos of resilience. Library information services were required to be digitalized.

Based on anecdotal evidence we have received from most sectors, many students became more aware of e-resources and started using the library journal databases at a greater speed that is supported by the recorded numbers of access or hits.

Online surveys were initiated for obtaining student feedback. We received feedback of the major impact on socio-economic and gender-based violence that soon followed student relocation in their own homes. COVID19 indeed brought into focus many unmet needs of the modern-day university student; ranging from self-employment opportunities in the city through tuition, Uber deliveries etc versus. rural living with no earning opportunity. The general anxiety among students was: When can we graduate? When can we stop being a burden to our parents?

As time progressed the digital engagement became apparent among diverse groups. Student centered community related e-activities, such as the Gavel Club, Societies related to social and cultural groups, leadership development through community service such as Rotaract and Leo clubs held their induction ceremonies on time through the digital mode. Addressing on-line, gender-based violence and psychological issues of COIVD 19, by the Golden Zs that comprises female and male medical students (supervised by a faculty representative of the Zonta Club of Colombo I) was an enriching and novel experience.

Online delivery of learning resources for students with disabilities and their special needs received special attention. The majority of students with special needs demonstrated a preference to attend a face-to-face teaching. The Faculty of Arts that accommodates the great majority of this special group that has developed a centre for disability research, education and practice (CEDREP) affiliated to the Department of Sociology. I am proud to state that CEDREP offers support to all students with disabilities irrespective of which faculty they belong to or which study stream they have chosen. They also individualize educational support and mitigate stigma and marginalization of the students with specific needs.

The digital transition was undertaken as a collective project to ensure a quality transition of Onsite Learning to Blended Learning at the University of Colombo. Blended learning is defined as an approach to education that effectively integrates classroom practices (teaching learning and assessment) with online learning (teaching learning and assessment) practices.

Soon after the COVID19 related shut down we had several inquiries made from highly rated universities in the USA. The foreign university looked to us as worthy partners to sustain their recruitment of Sri Lankan students at a discounted rate of 1/6 their original on campus fees with 10% for our university. Based on the discussion we did express an interest in partnership in the award of dual degrees through the “cyber campus” modality; which is a long process of planning. What brings into focus is that the format of blended learning provides opportunities for external partnerships to collaborate with foreign university in teaching and research.

Let me end by reiterating that consciously or unconsciously our inherent Lankan Culture encouraged us to counter threats imposed on higher education from the COVID19 pandemic by responding to the trendy management acronym VUCA through facing “Volatility with Vision, Uncertainty with Understanding, Complexity with Clarity and Ambiguity with Agility”.

Our fundamental values encouraged us to prioritize, risk manage, make pragmatic decisions, foster a change and seek sustainable solutions, while encouraging quick responses and a holistic outlook.

Features

Hanoi’s most popular street could kill you

Train Street started life as a razor-thin alley with a train rushing through it. Now, it’s swarmed with Instagrammable cafes and tourists who can’t stay away, despite the risks.

A train chugs through Hanoi, approaching a narrow passageway festooned with Chinese-style lanterns. Just as it screams into the station, a tourist jumps onto the tracks, attempting her most social-media friendly pose. Moments before the train strikes, its horn blaring into the humid air, she recoils to safety. Click, post.

It’s just an ordinary day on Hanoi’s Train Street, a 400m stretch of railway flanked by cafes where tourists nurse beers and watch, mesmerised, as trains roar past them at dangerously close proximity: sometimes crashing into tables and chairs.

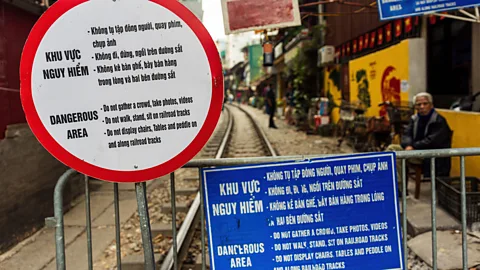

Fun? Evidently – in a few short years, Train Street has entered Vietnam’s pantheon of “must-see” attractions, along with Ha Long Bay and the Cu Chi Tunnels. But the Vietnamese government is less impressed; since the site went viral in 2017, it has attempted various shutdowns, first in 2019, then 2022 and most recently further investigations and crackdowns in 2025 after an incident where a selfie-snapping tourist was nearly dragged under an oncoming train’s wheels. Police barricades go up between train arrivals; edicts are issued to tour operators and bar owners.

The tourists come anyway.

How did an ordinary street become one of Vietnam’s hottest tourist attractions? It started innocently enough.

The North-South Railway was built by colonialist French forces in 1902, connecting Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City. Fifty-four years later, the General Department of Railway erected a series of squat buildings straddling a stretch in central Hanoi to house employees. By the 1970s, the area was considered a slum; residents regularly roused out of their sleep by trains rumbling through, their houses quaking.

“It was just an ordinary street with train tracks running through it,” said Minh Anh, a lifelong Hanoi local who works at local whisky distillery,

Alamy The Vietnamese government has attempted numerous shutdowns of the area (Credit: Alamy)Alamy

The Vietnamese government has attempted numerous shutdowns of the area (Credit: Alamy)

From ordinary to unmissable

How did an ordinary street become one of Vietnam’s hottest tourist attractions? It started innocently enough.

The North-South Railway was built by colonialist French forces in 1902, connecting Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City. Fifty-four years later, the General Department of Railway erected a series of squat buildings straddling a stretch in central Hanoi to house employees. By the 1970s, the area was considered a slum; residents regularly roused out of their sleep by trains rumbling through, their houses quaking.

“It was just an ordinary street with train tracks running through it,” said Minh Anh, a lifelong Hanoi local who works at local whisky distillery, Về Để Đi’. “When it started popping up all over social media, I was honestly surprised.”

Nhi Nguyn, a tour guide for A Taste of Hanoi, used to walk tourists through, just before it exploded in popularity. “People were still living ordinary lives there back then and there weren’t so many cafes next to the tracks,” she said. “It had a much more authentic feel: scooters were locked up just meters from the tracks, laundered clothes hung outside, and people were cooking outside on small gas stoves.”

. “When it started popping up all over social media, I was honestly surprised.”

Nhi Nguyn, a tour guide for

Alamy The Vietnamese government has attempted numerous shutdowns of the area (Credit: Alamy)Alamy

The Vietnamese government has attempted numerous shutdowns of the area (Credit: Alamy)

From ordinary to unmissable

How did an ordinary street become one of Vietnam’s hottest tourist attractions? It started innocently enough.

The North-South Railway was built by colonialist French forces in 1902, connecting Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City. Fifty-four years later, the General Department of Railway erected a series of squat buildings straddling a stretch in central Hanoi to house employees. By the 1970s, the area was considered a slum; residents regularly roused out of their sleep by trains rumbling through, their houses quaking.

“It was just an ordinary street with train tracks running through it,” said Minh Anh, a lifelong Hanoi local who works at local whisky distillery, Về Để Đi’. “When it started popping up all over social media, I was honestly surprised.”

Nhi Nguyn, a tour guide for A Taste of Hanoi, used to walk tourists through, just before it exploded in popularity. “People were still living ordinary lives there back then and there weren’t so many cafes next to the tracks,” she said. “It had a much more authentic feel: scooters were locked up just meters from the tracks, laundered clothes hung outside, and people were cooking outside on small gas stoves.”

, used to walk tourists through, just before it exploded in popularity. “People were still living ordinary lives there back then and there weren’t so many cafes next to the tracks,” she said. “It had a much more authentic feel: scooters were locked up just meters from the tracks, laundered clothes hung outside, and people were cooking outside on small gas stoves.”

In early 2013, Colm Pierce and Alex Sheal, co-founders of Hanoi-based photography tours Vietnam in Focus, launched a Hanoi on the Tracks tour to show visitors how local residents had adopted to the locomotive-sized challenge of living on railway tracks. Serendipitously, in June 2013, Instagram launched its new video-sharing feature. A year later, the Travel Channel show “Tough Trains” featured Pierce walking down Train Street with a camera crew, further enticing travellers.

In 2017, an enterprising resident started selling beer and coffee, inviting curious tourists to stay to watch the train go by. Neighbours noticed the economic opportunity and cafes and bars rapidly spread. Soon, the formerly derelict alley, now dubbed Phố Đường Tàu (literally: “Train Street”) became bedecked with colourful lanterns and Christmas lights. Visitors learned to time their arrival for 30 minutes before a scheduled train and the “classic” Train Street experience was cemented: upon entering the tracks, tourists were shepherded into rail-side bars by local merchants and plied with beers and coffee, until the train shrieked through, rattling plates and causing hearts to pound.

Julia Husum, a university student from Norway, visited Train Street in February 2026, and “loved” the experience. “We put our beer caps on the railway, and the train flattened it, creating souvenirs for us,” she said. “I’d go back again.”

Without the advent of social media, would Train Street have become popular? As a travel writer, I’ve witnessed dozens of would-be influencers’ death-defying acts, like scaling down a rocky cliff above Dubrovnik and standing atop the side wall of 14th-Century Charles Bridge in Prague; wistfully looking off into the distance as the camera flashes. I’ve come to conclude that Train Street is no different; here, too, visitors risk their own safety for a picture-perfect opportunity.

“Essentially social media has fuelled Train Street into what it is today, [where] tourists flock in droves to the area to feel the adrenaline of the passing train while sipping local coffee,” echoed Michael Stanbury, the creative director for Vietnam in Focus. “Even without the train, the Instagrammable decorated street holds a very Hanoian charm.”

Local debate; the government proposes halting passenger trains for good. And each attempted shutdown, tourists climb past the barricades. There are, to date, more than 100,000 posts tagging Train Street on Instagram. Men’s grooming blogger Adam Hurly visited because a friend had hyped it. “It felt more like an Instagram attraction rather than a neighbourhood street,” he admitted, noting that once the crowds arrive, it becomes congested and less enjoyable, “Especially if you’re just standing on the main sidewalk trying to get a picture.”

He added: “It’s one of those places that looks better in photos than it feels in reality.”

But Matthew Tran, an artisanal footwear designer who visits Hanoi regularly, loves the pull of Train Street.

“The coffees were absurdly overpriced, yet I paid for them every time because I couldn’t stop marvelling at how the place worked; how an entire economy could thrive in such an improbable space,” he said. “These vendors built something real out of something most people would call chaos – that, to me, is worth coming back for.”

He offers advice for future visitors: “It’s a unique experience you won’t get anywhere else. Although I wish more visitors would stop for a moment and remember that while it’s a tourist attraction to them, living beside those train tracks is someone else’s daily reality.”

Under more superficial reasons, visiting Train Street is similar to the appeal of visiting the Eiffel Tower during someone’s first visit to Paris, said Charlotte Russell, founder of The Travel Psychologist.

“Humans are a social species and if we perceive that other people are enjoying an experience, it is natural for us to want to do it too,” she said. “This goes back to our evolution, when we lived in small groups and it would be advantageous for us to emulate other people in this way. So the sense of fear of missing out that we experience when seeing other people visiting places like Train Street is part of being human.”

Bearix Stewart-Frommer, an American pre-med student, validates Russell’s theory: “I found out about Train Street from my mum,” she said. “I didn’t have some deep motivation to see it, but I was curious because it’s one of those quirky, very photogenic spots that people talk about on social media.”

But there may be a more deep-seated reason why we’re lured to such places, Russell notes: “With Train Street specifically, the risk element is part of what makes it so novel, especially those of us from countries like the UK… We are used to regulation and precaution, railings, barriers and painted lines that we must stand behind. In contrast, Train Street can feel unbelievable to see and experience… [it helps] us reflect on our own norms and realise that other perspectives do exist.”

Local tour guide Phuong Loan Ngo offers one such alternative perspective: “The economic boost is undeniable, giving families who live along Train Street financial opportunities,” she said. “On the other hand, there are cultural challenges too. When an area becomes a ‘spotlight’ for social media, a place’s historical and cultural heritage can get lost. Instead of learning about how this railway has functioned since the colonial era, people often leave with only a photo, missing the true soul of the neighbourhood.”

The irony is that Vietnam in Focus has now moved their photography tours to another, far-less trammelled part of the railway, so they can show visitors that old, track-side way of life.

“As with all good things, the popularity of Train Street and the crowds it attracts are spreading,” said Sheal. “Thankfully, we have scoured Hanoi and found a fantastic local market that runs along the Hanoian railway further out in the suburbs – a new attraction.”

That is, until the social-media-obsessed travel masses find out about it. For better or worse, the unbearable lightness of Train Street is a permanent, but moveable feast.

[BBC]

Features

An innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

After nearly two decades of on-and-off negotiations that began in 2007, India and the European Union formally finally concluded a comprehensive free trade agreement on 27 January 2026. This agreement, the India–European Union Free Trade Agreement (IEUFTA), was hailed by political leaders from both sides as the “mother of all deals,” because it would create a massive economic partnership and greatly increase the current bilateral trade, which was over US$ 136 billion in 2024. The agreement still requires ratification by the European Parliament, approval by EU member states, and completion of domestic approval processes in India. Therefore, it is only likely to come into force by early 2027.

An Innocent Bystander

When negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement between India and the European Union were formally launched in June 2007, anticipating far-reaching consequences of such an agreement on other developing countries, the Commonwealth Secretariat, in London, requested the Centre for Analysis of Regional Integration at the University of Sussex to undertake a study on a possible implication of such an agreement on other low-income developing countries. Thus, a group of academics, led by Professor Alan Winters, undertook a study, and it was published by the Commonwealth Secretariat in 2009 (“Innocent Bystanders—Implications of the EU-India Free Trade Agreement for Excluded Countries”). The authors of the study had considered the impact of an EU–India Free Trade Agreement for the trade of excluded countries and had underlined, “The SAARC countries are, by a long way, the most vulnerable to negative impacts from the FTA. Their exports are more similar to India’s…. Bangladesh is most exposed in the EU market, followed by Pakistan and Sri Lanka.”

Trade Preferences and Export Growth

Normally, reduction of price through preferential market access leads to export growth and trade diversification. During the last 19-year period (2015–2024), SAARC countries enjoyed varying degrees of preferences, under the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP). But, the level of preferential access extended to India, through the GSP (general) arrangement, only provided a limited amount of duty reduction as against other SAARC countries, which were eligible for duty-free access into the EU market for most of their exports, via their LDC status or GSP+ route.

However, having preferential market access to the EU is worthless if those preferences cannot be utilised. Sri Lanka’s preference utilisation rate, which specifies the ratio of eligible to preferential imports, is significantly below the average for the EU GSP receiving countries. It was only 59% in 2023 and 69% in 2024. Comparative percentages in 2024 were, for Bangladesh, 96%; Pakistan, 95%; and India, 88%.

As illustrated in the table above, between 2015 and 2024, the EU’s imports from SAARC countries had increased twofold, from US$ 63 billion in 2015 to US$ 129 billion by 2024. Most of this growth had come from India. The imports from Pakistan and Bangladesh also increased significantly. The increase of imports from Sri Lanka, when compared to other South Asian countries, was limited. Exports from other SAARC countries—Afghanistan, Bhutan, Nepal, and the Maldives—are very small and, therefore, not included in this analysis.

Why the EU – India FTA?

With the best export performance in the region, why does India need an FTA with the EU?

Because even with very impressive overall export growth, in certain areas, India has performed very poorly in the EU market due to tariff disadvantages. In addition to that, from January 2026, the EU has withdrawn GSP benefits from most of India’s industrial exports. The FTA clearly addresses these challenges, and India will improve her competitiveness significantly once the FTA becomes operational.

Then the question is, what will be its impact on those “innocent bystanders” in South Asia and, more particularly, on Sri Lanka?

To provide a reasonable answer to this question, one has to undertake an in-depth product-by-product analysis of all major exports. Due to time and resource constraints, for the purpose of this article, I took a brief look at Sri Lanka’s two largest exports to the EU, viz., the apparels and rubber-based products.

Fortunately, Sri Lanka’s exports of rubber products will be only nominally impacted by the FTA due to the low MFN duty rate. For example, solid tyres and rubber gloves are charged very low (around 3%) MFN duty and the exports of these products from Sri Lanka and India are eligible for 0% GSP duty at present. With an equal market access, Sri Lanka has done much better than India in the EU market. Sri Lanka is the largest exporter of solid tyres to the EU and during 2024 our exports were valued at US$180 million.

On the other hand, Tariffs MFN tariffs on Apparel at 12% are relatively high and play a big role in apparel sourcing. Even a small difference in landed cost can shift entire sourcing to another supplier country. Indian apparel exports to the EU faced relatively high duties (8.5% – 12%), while competitors, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, are eligible for preferential access. In addition to that, Bangladesh enjoys highly favourable Rules of Origin in the EU market. The impact of these different trade rules, on the EU’s imports, is clearly visible in the trade data.

During the last 10 years (2015-2024), the EU’s apparel imports from Bangladesh nearly doubled, from US$15.1 billion, in 2015, to US$29.1 billion by 2024, and apparel imports from Pakistan more than doubled, from US$2.3 billion to US$5.5 billion. However, apparel imports from Sri Lanka increased only from US$1.3 billion in 2015 to US$2.2 billion by 2024. The impressive export growth from Pakistan and Bangladesh is mostly related to GSP preferences, while the lackluster growth of Sri Lankan exports was largely due to low preference utilisation. Nearly half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports faced a 12% tariff due to strict Rules of Origin requirements to qualify for GSP.

During the same period, the EU’s apparel imports from India only showed very modest growth, from US$ 5.3 billion, in 2015, to US$ 6.3 billion in 2024. The main reason for this was the very significant tariff disadvantage India faced in the EU market. However, once the FTA eliminates this gap, apparel imports from India are expected to grow rapidly.

According to available information, Indian industry bodies expect US$ 5-7 billion growth of textiles and apparel exports during the first three years of the FTA. This will create a significant trade diversion, resulting in a decline in exports from China and other countries that do not enjoy preferential market access. As almost half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports are not eligible for GSP, the impact on our exports will also be fierce. Even in the areas where Sri Lanka receives preferential duty-free access, the arrival of another large player will change the market dynamics greatly.

A Passive Onlooker?

Since the commencement of the negotiations on the EU–India FTA, Bangladesh and Pakistan have significantly enhanced the level of market access through proactive diplomatic interventions. As a result, they have substantially increased competitiveness and the market share within the EU. This would help them to minimize the adverse implications of the India–EU FTA on their exports. Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU market have not performed that well. The challenges in that market will intensify after 2027.

As we can clearly anticipate a significant adverse impact from the EU-India FTA, we should start to engage immediately with the European Commission on these issues without being passive onlookers. For example, the impact of the EU-India FTA should have been a main agenda item in the recently concluded joint commission meeting between the European Commission and Sri Lanka in Colombo.

Need of the Hour – Proactive Commercial Diplomacy

In the area of international trade, it is a time of turbulence. After the US Supreme Court judgement on President Trump’s “reciprocal tariffs,” the only prediction we can make about the market in the United States market is its continued unpredictability. India concluded an FTA with the UK last May and now the EU-India FTA. These are Sri Lanka’s largest markets. Now to navigate through these volatile, complex, and rapidly changing markets, we need to move away from reactive crisis management mode to anticipatory action. Hence, proactive commercial diplomacy is the need of the hour.

(The writer can be reached at senadhiragomi@gmail.com)

By Gomi Senadhira

Features

Educational reforms: A perspective

Dr. B.J.C. Perera (Dr. BJCP) in his article ‘The Education cross roads: Liberating Sri Lankan classroom and moving ahead’ asks the critical question that should be the bedrock of any attempt at education reform – ‘Do we truly and clearly understand how a human being learns? (The Island, 16.02.2026)

Dr. BJCP describes the foundation of a cognitive architecture taking place with over a million neural connections occurring in a second. This in fact is the result of language learning and not the process. How do we ‘actually’ learn and communicate with one another? Is a question that was originally asked by Galileo Galilei (1564 -1642) to which scientists have still not found a definitive answer. Naom Chomsky (1928-) one of the foremost intellectuals of our time, known as the father of modern linguistics; when once asked in an interview, if there was any ‘burning question’ in his life that he would have liked to find an answer for; commented that this was one of the questions to which he would have liked to find the answer. Apart from knowing that this communication takes place through language, little else is known about the subject. In this process of learning we learn in our mother tongue and it is estimated that almost 80% of our learning is completed by the time we are 5 years old. It is critical to grasp that this is the actual process of learning and not ‘knowledge’ which tends to get confused as ‘learning’. i.e. what have you learnt?

The term mother tongue is used here as many of us later on in life do learn other languages. However, there is a fundamental difference between these languages and one’s mother tongue; in that one learns the mother tongue- and how that happens is the ‘burning question’ as opposed to a second language which is taught. The fact that the mother tongue is also formally taught later on, does not distract from this thesis.

Almost all of us take the learning of a mother tongue for granted, as much as one would take standing and walking for granted. However, learning the mother tongue is a much more complex process. Every infant learns to stand and walk the same way, but every infant depending on where they are born (and brought up) will learn a different mother tongue. The words that are learnt are concepts that would be influenced by the prevalent culture, religion, beliefs, etc. in that environment of the child. Take for example the term father. In our culture (Sinhala/Buddhist) the father is an entity that belongs to himself as well as to us -the rest of the family. We refer to him as ape thaththa. In the English speaking (Judaeo-Christian) culture he is ‘my father’. ‘Our father’ is a very different concept. ‘Our father who art in heaven….

All over the world education is done in one’s mother tongue. The only exception to this, as far as I know, are the countries that have been colonised by the British. There is a vast amount of research that re-validates education /learning in the mother tongue. And more to the point, when it comes to the comparability of learning in one’s own mother tongue as opposed to learning in English, English fails miserably.

Education /learning is best done in one’s mother tongue.

This is a fact. not an opinion. Elegantly stated in the words of Prof. Tove Skutnabb-Kangas-“Mother tongue medium education is controversial, but ‘only’ politically. Research evidence about it is not controversial.”

The tragedy is that we are discussing this fundamental principle that is taken for granted in the rest of the world. It would not be not even considered worthy of a school debate in any other country. The irony of course is, that it is being done in English!

At school we learnt all of our subjects in Sinhala (or Tamil) right up to University entrance. Across the three streams of Maths, Bio and Commerce, be it applied or pure mathematics, physics, chemistry, zoology, botany economics, business, etc. Everything from the simplest to the most complicated concept was learnt in our mother tongue. An uninterrupted process of learning that started from infancy.

All of this changed at university. We had to learn something new that had a greater depth and width than anything we had encountered before in a language -except for a very select minority – we were not at all familiar with. There were students in my university intake that had put aside reading and writing, not even spoken English outside a classroom context. This I have been reliably informed is the prevalent situation in most of the SAARC countries.

The SAARC nations that comprise eight countries (Sri Lanka, Maldives, India, Pakistan Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan) have 21% of the world population confined to just 3% of the earth’s land mass making it probably one of the most densely populated areas in the world. One would assume that this degree of ‘clinical density’ would lead to a plethora of research publications. However, the reality is that for 25 years from 1996 to 2021 the contribution by the SAARC nations to peer reviewed research in the field of Orthopaedics and Sports medicine- my profession – was only 1.45%! Regardless of each country having different mother tongues and vastly differing socio-economic structures, the common denominator to all these countries is that medical education in each country is done in a foreign language (English).

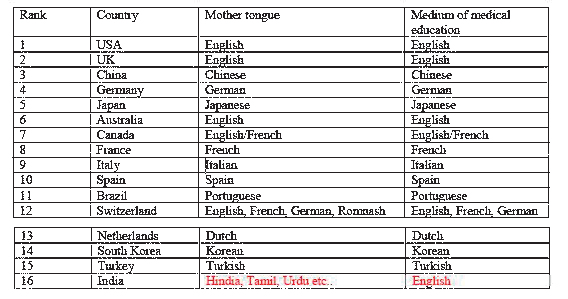

The impact of not learning in one’s mother tongue can be illustrated at a global level. This can be easily seen when observing the research output of different countries. For example, if one looks at orthopaedics and sports medicine (once again my given profession for simplicity); Table 1. shows the cumulative research that has been published in peer review journals. Despite now having the highest population in the world, India comes in at number 16! It has been outranked by countries that have a population less than one of their states. Pundits might argue giving various reasons for this phenomenon. But the inconvertible fact remains that all other countries, other than India, learn medicine in their mother tongue.

(See Table 1) Mother tongue, medium of education in country rank order according to the volume of publications of orthopaedics and sports medicine in peer reviewed journals 1996 to 2024. Source: Scimago SCImago journal (https://www.scimagojr.com/) has collated peer review journal publications of the world. The publications are categorized into 27 categories. According to the available data from 1996 to 2024, China is ranked the second across all categories with India at the 6th position. China is first in chemical engineering, chemistry, computer science, decision sciences, energy, engineering, environmental science, material sciences, mathematics, physics and astronomy. There is no subject category that India is the first in the world. China ranks higher than India in all categories except dentistry.

The reason for this difference is obvious when one looks at how learning is done in China and India.

The Chinese learn in their mother tongue. From primary to undergraduate and postgraduate levels, it is all done in Chinese. Therefore, they have an enormous capacity to understand their subject matter just not itself, but also as to how it relates to all other subjects/ themes that surround it. It is a continuous process of learning that evolves from infancy onwards, that seamlessly passes through, primary, secondary, undergraduate and post graduate education, research, innovation, application etc. Their social language is their official language. The language they use at home is the language they use at their workplaces, clubs, research facilities and so on.

In India higher education/learning is done in a foreign language. Each state of India has its own mother tongue. Be it Hindi, Tamil, Urdu, Telagu, etc. Infancy, childhood and school education to varying degrees is carried out in each state according to their mother tongue. Then, when it comes to university education and especially the ‘science subjects’ it takes place in a foreign tongue- (English). English remains only as their ‘research’ language. All other social interactions are done in their mother tongue.

India and China have been used as examples to illustrate the point between learning in the mother tongue and a foreign tongue, as they are in population terms comparable countries. The unpalatable truth is that – though individuals might have a different grasp of English- as countries, the ability of SAARC countries to learn and understand a subject in a foreign language is inferior to the rest of the world that is learning the same subject in its mother tongue. Imagine the disadvantage we face at a global level, when our entire learning process across almost all disciplines has been in a foreign tongue with comparison to the rest of the world that has learnt all these disciplines in their mother tongue. And one by-product of this is the subsequent research, innovation that flows from this learning will also be inferior to the rest of the world.

All this only confirms what we already know. Learning is best done in one’s mother tongue! .

What needs to be realised is that there is a critical difference between ‘learning English’ and ‘learning in English’. The primary-or some may argue secondary- purpose of a university education is to learn a particular discipline, be it medicine, engineering, etc. The students- have been learning everything up to that point in Sinhala or Tamil. Learning their discipline in their mother tongue will be the easiest thing for them. The solution to this is to teach in Sinhala or Tamil, so it can be learnt in the most efficient manner. Not to lament that the university entrant’s English is poor and therefore we need to start teaching English earlier on.

We are surviving because at least up to the university level we are learning in the best possible way i.e. in our mother tongue. Can our methods be changed to be more efficient? definitely. If, however, one thinks that the answer to this efficient change in the learning process is to substitute English for the mother tongue, it will defeat the very purpose it is trying to overcome. According to Dr. BJCP as he states in his article; the current reforms of 2026 for the learning process for the primary years, centre on the ‘ABCDE’ framework: Attendance, Belongingness, Cleanliness, Discipline and English. Very briefly, as can be seen from the above discussion, if this is the framework that is to be instituted, we should modify it to ABCDEF by adding a F for Failure, for completeness!

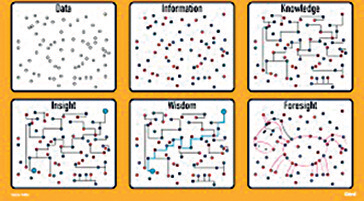

(See Figure 1) The components and evolution of learning: Data, information, knowledge, insight, wisdom, foresight As can be seen from figure 1. data and information remain as discrete points. They do not have interconnections between them. It is these subsequent interconnections that constitute learning. And these happen best through the mother tongue. Once again, this is a fact. Not an opinion. We -all countries- need to learn a second language (foreign tongue) in order to gather information and data from the rest of the world. However, once this data/ information is gathered, the learning needs to happen in our own mother tongue.

Without a doubt English is the most universally spoken language. It is estimated that almost a quarter of the world speaks English as its mother tongue or as a second language. I am not advocating to stop teaching English. Please, teach English as a second language to give a window to the rest of the world. Just do not use it as the mode of learning. Learn English but do not learn in English. All that we will be achieving by learning in English, is to create a nation of professionals that neither know English well nor their subject matter well.

If we are to have any worthwhile educational reforms this should be the starting pivotal point. An education that takes place in one’s mother tongue. Not instituting this and discussing theories of education and learning and proposing reforms, is akin to ‘rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic’. Sadly, this is not some stupendous, revolutionary insight into education /learning. It is what the rest of the world has been doing and what we did till we came under British rule.

Those who were with me in the medical faculty may remember that I asked this question then: Why can’t we be taught in Sinhala? Today, with AI, this should be much easier than what it was 40 years ago.

The editorial of this newspaper has many a time criticised the present government for its lackadaisical attitude towards bringing in the promised ‘system change’. Do this––make mother tongue the medium of education /learning––and the entire system will change.

by Dr. Sumedha S. Amarasekara

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSeeing is believing – the silent scale behind SriLankan’s ground operation

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoBathiya & Santhush make a strategic bet on Colombo

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoBarking up the wrong tree