Features

DS Senanayake, the all time great: “If he did not live, Ceylon would have been very different”

(Excerpted from Selected Journalism by HAJ Hulugalle)

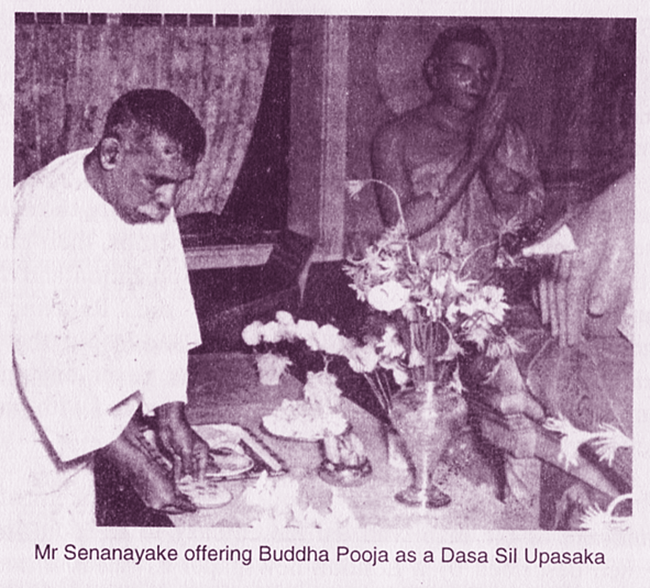

One morning in March 1952, Don Stephen Senanayake, Ceylon’s first Prime Minister, fell off the horse he was riding on the Galle Face Green in Colombo and died 33 hours later. He was in his 68th year and was probably the victim of a stroke which made him lose control of the horse. He was found laid out on the turf with his face downwards and bleeding from his nose. The nation mourned the man who had led it to independence and had made the parched lands of the Island bloom.

Those who knew Mr. Senanayake or only saw him, will recall his burly figure, infectious smile and unfailing kindness. A generation born since his death has now reached adult status. Only a few of his age group are still around. Forty eight years have elapsed since he entered upon a political career as the elected Member for Negombo in the Legislative Council. A fresh look at his life and work, 21 years after his death (when this article was written) can shed useful light on many of the problems with which the country is beset today.

The years in which Mr. Senanayake was the acknowledged national leader are important not only for his achievements in gaining independence after centuries of Colonial rule and in introducing a new dimension to agricultural development. They mark a shift in values affecting the structure of our society. Under the impact of adult franchise and free education, which came when he was Prime Minister, the outlook and expectations of the common people changed significantly and irretrievably.

He may not have spelt all this out in his own thinking. He was born in the Victorian age when, in the Colonies at any rate, the people’s wishes counted for little. Although he lived in the town, Mr. Senanayake’s heart was in the country. Political reform had no meaning for him other than as a means of providing the rural folk of the country with a new and more abundant life. He had his misgivings about foisting an inferior type of free education that took no account of the needs and conditions of the country. Nevertheless, the effect of the two changes referred to is being now felt at every level of the social and political life of the people of Ceylon.

Mr. Senanayake took up politics seriously after the riots of 1915 when several Buddhist leaders, like himself and his two brothers who were in no way connected with the disturbances, were incarcerated. The conviction was then forced on him that, until the Ceylonese became fully responsible for the Government, there was no way of preventing such abuses of power and of solving the political and economic problems of the country.

In the earlier stages of the campaign for freedom he was more a camp-follower than a pace-setter. But after he became a Member of the Legislative Council in 1924, he knew what he wanted for Ceylon and was determined to get it. After he succeeded Sir Baron Jayatilaka as Leader of the State Council, in the early stages of the last war, he had the reins in his hands. Six years of agitation and negotiation produced the desired result, namely, political independence for Sri Lanka as a member of the Commonwealth.

He grasped firmly the substance of independence, leaving it to those who came after him to do better if they could. The smug comment is sometimes heard that Ceylon gained her independence too easily. Other countries in the Colonial Empire did not get it without bloodshed, civil war and non-co-operation. Mr. Senanayake’s tactics ruled out such measures. His own warm personality helped, and confidence begat confidence. On appropriate occasions he could act on the principle that “the gentler gamester is the soonest winner.”

Summing up Mr. Senanayake’s achievement, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, said: “We of this generation, wherever we may live, have passed through this great period of transition and have seen the face of Asia change in this process. The change continues. Leading personalities in different countries become the symbols of this period of transition and thus become in some ways agents of historic destiny. In Ceylon, Don Stephen Senanayake was such a personality, who impressed himself not only in Ceylon, but on a wider sphere. He should be remembered as a person who helped about the transition to freedom and then to consolidate the freedom that had come.”

After the dusty and sometimes bitter conflicts over communal representation in the legislature had ended, Mr. Senanayake led a united people to the goal of independence. He was able to persuade the State Council, with the exception of two members who represented Indian interests and a Sinhalese ‘independent’, to accept the Soulbury Constitution which, as Sir Ivor Jennings has pointed out, was largely his Constitution.

“The belief that the Soulbury Commission produced the Constitution,” wrote Sir Ivor, “is due partly to the fact that people doubted whether Mr. Senanayake had the capacity to produce a Constitution. After all he had never passed the Matriculation. This is, however, seriously to underrate Mr. Senanayake’s intellectual capacity. Naturally he relied heavily on his advisers; any Minister who does not is bound to fail. What is more, he left insignificant detail to his advisers. Nevertheless, he had an excellent grasp of fundamental principles, and he quickly seized the essence of any problem that might become controversial.

“If after explanation he began, “As a matter of fact” or “Actually,” his advisers at once knew that something was wrong. If they were unable to convince him, they were told in the nicest possible way that they had better get away and think again. Mr. Senanayake could not have foreseen the full impact of the forces he helped to release. Those who advised him, and he himself, had an almost mystical faith in the British parliamentary system which, as we know, functions best with a homogeneous population.

“He envisaged a united people entering upon a heritage that had eluded them too long. Though he succeeded in winning over the leaders of the minorities to his way of thinking, he did not perhaps pay sufficient attention to the fears and emotions of those they represented, which fact in due course gave momentum to the formation of the Federal Party by a section of the Ceylon Tamils.

“He believed that, given a fair field and the rules of the game, the industry and inherent ability of the Tamils and other minorities would see them through in any competition. He was careful to do nothing to widen the gaps or emphasize the differences, as the following incidents demonstrate. One day a leading Buddhist layman and two influential prelates called on him. He welcomed them with his usual courtesy and listened patiently to what they had to say to him. They asked that Sinhalese should at once be made the country’s official language and Buddhism the State religion.

“He thanked them and with good grace told them that he could not consider their request until the more urgent problem of food, shelter and employment had been resolved. On another occasion a deputation of backbenchers of his party represented to him that the new industries like cement, chemicals and paper were located in the Northern and Eastern Provinces in which the Sinhalese were in a small minority. He replied that it was his responsibility to attend to the needs of all sections of the community and a united nation could be built up only by the majority being generous to the minorities.

“He was indeed the friend of all communities. Mr. S. J. V. Chelvanayagam, the leader of the Federal Party, in a tribute to Mr. Senanayake, said that “it was the personal qualities of the man that helped him to achieve so much success in the very high office that he filled in the affairs of this country. Differences of opinion did not in any way diminish my respect or regard for Mr. Senanayake. I admired the love he had for his people. He had a shining faith in their future greatness and, according to his lights, he worked for its achievement untiringly and consistently. Many a time I had wished that in the ranks to which I belonged there were to be found one like Mr. Senanayake, so consistently loyal and so full of hope and ultimate success.”

It would take a longer article than this to do justice to Mr. Senanayake’s achievements in agricultural development. He was Minister of Agriculture for the 14 years of the two State Councils. During those years he transformed the pattern of peasant agriculture. He built or restored large and small tanks, which feed several 100,000 acres, set up colonization schemes, established new towns, started research stations, promoted rural credit and co-operative marketing, encouraged extension work and sent trained men into the field to help the peasant farmer to improve his crops by the adoption of scientific methods.

As one of his colleagues in this work, Dr. R. L. Brohier has written, “he saw the necessity for improving the quality of crops, for growing a wide range of varieties to ensure balanced dietary intake, and the need for inculcating animal husbandry. He also visualized that there must be Government financial assistance for the colonist to set himself up, technical guidance and a system of easy and orderly marketing.”

Mr. Senanayake was justly proud of the progress made in agricultural development during the years when he bore the main responsibility for its direction and accomplishment. But he saw many years of work ahead. He did not talk about his achievements but rather loved to show what had been done and how it was done. On one occasion when he was needled by a Marxist critic in Parliament for spending too much on his irrigation schemes, he was compelled to say, more in sorrow than in anger, “During the

period of my Ministry, that is 14 years, I have had tanks built and natural sources tapped which will make it possible with a little development to have at least another million acres to cultivate when we have the manpower.”

He was of course a convinced anti-Marxist and did not agree that human nature could be changed by changing institutions. When in December 1947, Dr. Colvin R. de Silva, had lectured him in Parliament on how the country’s agriculture should be developed, Mr. Senanayake, who had spent more years as a practical agriculturist than the life span of his critic, rejoined:

“My good friend the Member for Wellawatte-Galkissa, for whom I have the greatest admiration, is so much above his associates in intellect and all those things, that he is under the impression that there is nothing in this world that he does not know. I have a great admiration for his ability, but I wish to tell him that he does not know everything in this world. There are more things in heaven and earth than enter into his philosophy. He spoke of agriculture. That reminded me of a story that I had heard sometime ago.”

Mr. Senanayake then proceeded to relate the story. There was a farmer in the village who was suddenly afflicted by a gripe. Suffering agonies he shouted to his young son to run to the doctor and get him some medicine. The boy went to a house which had a board with the name of “Dr. So and So” on it. Meeting the doctor, the boy told him about his father’s illness and the suffering he was

undergoing. The doctor replied, “Well, I am only a veterinary surgeon, I would give a horse a pound of Epsom Salts in a bucket of water. I suggest that you give your father half that and I think it would settle his stomach ache. The next day the veterinary surgeon saw the youth and asked him how his father was faring. The boy replied, “Oh, you are a wonderful doctor. You know, even after his death he purged three times.”

“So, I would tell my veterinary friend,” added Mr. Senanayake, “that of human beings and human problems, he knows nothing. He may be a great man and a well-read person who knows a lot about Russia. But, although I do not compare myself with him, I can assure him that I know more about soil and cultivation than he knows and will ever know.”

He was a formidable debater, relying more on his experience of human nature and a native shrewdness than on dialectical prowess. The best tribute to him in this capacity was paid by Dr. N. M. Perera whose specialty is parliamentary institutions. “In a sense,” said Dr. Perera, “he filled the Council by his very presence. I have never known a man more devoted to his duty or more consistent in his attendance. He followed every debate closely. He never missed a good point, however humble the quarter from which it emanated. This was a remarkable performance for one so overburdened with the innumerable cares of office. His astuteness and shrewdness as a parliamentarian – I use the words in no

disrespectful sense – were almost uncanny.

“When one recollects his early life, this is indeed a remarkable achievement. He was quick to sense and grasp a situation while others were hesitant and groping. Others may have been more learned, but he was more knowledgeable. As a debater he was the equal of the best in the land. He may not have indulged in sonorous language, his phraseology may not have been elegant, his diction may have been imperfect, but his quick-wittedness was remarkable. Quick to pounce upon his opponent’s weak points, he knew the art of getting at the heart of a debate…. He had a remarkable capacity to understand all the things that went on in his Government. There was no Department that he did not know intimately.”

Mr. Senanayake had no difficulty in meeting people, whatever their station in life, at a human level. No townsman or villager, who went to him with a personal problem was turned away from the little downstairs room at Temple Trees where he relaxed. If the visitor had been waiting for him, he would ask Carolis, his faithful man servant and companion, to fetch him a drink, usually of orange juice, white he, himself went in to divest himself of his office clothes. The Prime Minister would sometimes cool himself by pouring water on his head, the noise of which could be heard, and he would then emerge dressed in a sarong and a singlet.

Sir John Kotalawala made a just comment when he said, “No man was too small for his attention if he had the time, and somehow he would find the time. No man who went to him can ever forget the sincerity with which he promised to look into his grievance.” When Mr. Senanayake died, an

Indian labourer on a tea estate went to his European master and said, “Aiyo, periyah manushan, mickam nalla manushan” – “Oh, he was a great man and a good man.”

He never missed the opportunity to get closer to the people – speaking to them about their crops, their children and their livestock – when he visited the colonization and village expansion schemes, which he frequently did. Relaxing in a resthouse in the evening he would chat with and inspire the young officials who accompanied him. There was never any lack of communication between him and those who worked with him and those for whose benefit they both worked.

In what I have written above, I have spoken of Mr. Senanayake as the man who led his country to freedom in what was then described by a London newspaper as “the most untroubled country in Asia,” as the pioneer of land development, builder of tanks, as parliamentarian and administrator. What impact did he make on the world outside Ceylon? On receiving the news of his death, Mr. Winston Churchill said, “The Commonwealth is the poorer without him and the wise counsel he always gave.” Mr. Attlee, the Labour Prime Minister, during whose term of office Ceylon became an independent nation said, “He was a man of great personal charm. Ceylon was extremely lucky to have had such a man to inaugurate a new era of full equality in the Commonwealth.” Sir Robert Menzies, the Prime Minister of Australia said, “D. S. Senanayake was a man of enormous breadth of vision and of singular personal attraction. He pursued his objectives – and he had a wonderful capacity for defining them precisely – with sincerity and forcefulness, yet always with a due regard for the rights and feelings of others.”

Mr. Senanayake had indeed won respect and admiration not only among his own people but far beyond these shores and he held an honoured place among the leaders of the nations. “History,” wrote Lord Soulbury, “is the impact of the individual man of mark upon his contemporaries. In short, it is the great men who make history: D. S. Senanayake was a great man and if he had not lived Ceylon would have been very different.’

(From D.S. Senanayake’s Place in the History of His Country, 1972)

Features

Ukraine crisis continuing to highlight worsening ‘Global Disorder’

The world has unhappily arrived at the 4th anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and as could be seen a resolution to the long-bleeding war is nowhere in sight. In fact the crisis has taken a turn for the worse with the Russian political leadership refusing to see the uselessness of its suicidal invasion and the principal power groupings of the West even more tenaciously standing opposed to the invasion.

The world has unhappily arrived at the 4th anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and as could be seen a resolution to the long-bleeding war is nowhere in sight. In fact the crisis has taken a turn for the worse with the Russian political leadership refusing to see the uselessness of its suicidal invasion and the principal power groupings of the West even more tenaciously standing opposed to the invasion.

One fatal consequence of the foregoing trends is relentlessly increasing ‘Global Disorder’ and the heightening possibility of a regional war of the kind that broke out in Europe in the late thirties at the height of Nazi dictator Adolph Hitler’s reckless territorial expansions. Needless to say, that regional war led to the Second World War. As a result, sections of world opinion could not be faulted for believing that another World War is very much at hand unless peace making comes to the fore.

Interestingly, the outbreak of the Second World War coincided with the collapsing of the League of Nations, which was seen as ineffective in the task of fostering and maintaining world law and order and peace. Needless to say, the ‘League’ was supplanted by the UN and the question on the lips of the informed is whether the fate of the ‘League’ would also befall the UN in view of its perceived inability to command any authority worldwide, particularly in the wake of the Ukraine blood-letting.

The latter poser ought to remind the world that its future is gravely at risk, provided there is a consensus among the powers that matter to end the Ukraine crisis by peaceful means. The question also ought to remind the world of the urgency of restoring to the UN system its authority and effectiveness. The spectre of another World War could not be completely warded off unless this challenge is faced and resolved by the world community consensually and peacefully.

It defies comprehension as to why the Russian political leadership insists on prolonging the invasion, particularly considering the prohibitive human costs it is incurring for Russia. There is no sign of Ukraine caving-in to Russian pressure on the battle field and allowing Russia to have its own way and one wonders whether Ukraine is going the way of Afghanistan for Russia. If so the invasion is an abject failure.

The Russian political leadership would do well to go for a negotiated settlement and thereby ensure peace for the Russian people, Ukraine and the rest of Europe. By drawing on the services of the UN for this purpose, Russian political leaders would be restoring to the UN its dignity and rightful position in the affairs of the world.

Russia, meanwhile, would also do well not to depend too much on the Trump administration to find a negotiated end to the crisis. This is in view of the proved unreliability of the Trump government and the noted tendency of President Trump to change his mind on questions of the first importance far too frequently. Against this backdrop the UN would prove the more reliable partner to work with.

While there is no sign of Russia backing down, there are clearly no indications that going forward Russia’s invasion would render its final aims easily attainable either. Both NATO and the EU, for example, are making it amply clear that they would be staunchly standing by Ukraine. That is, Ukraine would be consistently armed and provided for in every relevant respect by these Western formations. Given these organizations’ continuing power it is difficult to see Ukraine being abandoned in the foreseeable future.

Accordingly, the Ukraine war would continue to painfully grind on piling misery on the Ukraine and Russian people. There is clearly nothing in this war worth speaking of for the two peoples concerned and it will be an action of the profoundest humanity for the Russian political leadership to engage in peace talks with its adversaries.

It will be in order for all countries to back a peaceful solution to the Ukraine nightmare considering that a continued commitment to the UN Charter would be in their best interests. On the question of sovereignty alone Ukraine’s rights have been grossly violated by Russia and it is obligatory on the part of every state that cherishes its sovereignty to back Ukraine to the hilt.

Barring a few, most states of the West could be expected to be supportive of Ukraine but the global South presents some complexities which get in the way of it standing by the side of Ukraine without reservations. One factor is economic dependence on Russia and in these instances countries’ national interests could outweigh other considerations on the issue of deciding between Ukraine and Russia. Needless to say, there is no easy way out of such dilemmas.

However, democracies of the South would have no choice but to place principle above self interest and throw in their lot with Ukraine if they are not to escape the charge of duplicity, double talk and double think. The rest of the South, and we have numerous political identities among them, would do well to come together, consult closely and consider as to how they could collectively work towards a peaceful and fair solution in Ukraine.

More broadly, crises such as that in Ukraine, need to be seen by the international community as a challenge to its humanity, since the essential identity of the human being as a peacemaker is being put to the test in these prolonged and dehumanizing wars. Accordingly, what is at stake basically is humankind’s fundamental identity or the continuation of civilization. Put simply, the choice is between humanity and barbarity.

The ‘Swing States’ of the South, such as India, Indonesia, South Africa and to a lesser extent Brazil, are obliged to put their ‘ best foot forward’ in these undertakings of a potentially historic nature. While the humanistic character of their mission needs to be highlighted most, the economic and material costs of these wasting wars, which are felt far and wide, need to be constantly focused on as well.

It is a time to protect humanity and the essential principles of democracy. It is when confronted by the magnitude and scale of these tasks that the vital importance of the UN could come to be appreciated by human kind. This is primarily on account of the multi-dimensional operations of the UN. The latter would prove an ideal companion of the South if and when it plays the role of a true peace maker.

Features

JVP: From “Hammer and Sickle” to Social Democracy – Or not?

The National People’s Power (NPP), led by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), came to power promising democratic renewal and long-awaited economic, educational, healthcare, and social transformation. It pledged to build a modern Sri Lanka rooted in democratic values while steering the country toward its vision of Democratic Socialism. For many supporters, the NPP’s rise to the pinnacle of political power represents a historic opportunity to reset the nation’s direction.

Yet recent developments have stirred unease. Statements by several senior ministers and certain policy signals have prompted critics to question whether the government’s path remains firmly democratic. Some warn that in the pursuit of rapid development and social justice, central pillars of the NPP’s election campaign, there may be a growing temptation to consolidate power in ways that edge toward policies of old “Hammer & Sickle.”

Is the NPP committed to pluralistic democratic socialism, or is Sri Lanka witnessing the early signs of a more centralised political model? To answer this question, it is necessary to revisit the JVP’s ideological history, examine the pressures that shape governing parties once in power, and weigh the potential consequences, both promising and perilous, of any shift in direction.

History of the JVP

The JVP emerged in the mid-1960s with a revolutionary agenda, mobilising youth through its Five Lecture Programme, which criticised capitalist policies, questioned the country’s “real independence,” opposed Indian influence, and called for armed struggle. This ideology culminated in the 1971-armed uprising against the elected government, leading to widespread violence, a harsh state crackdown, mass arrests, and the banning of the party.

Although suppressed, the JVP later re-entered democratic politics after its leaders were imprisoned and eventually pardoned. In the 1980s, after electoral defeat, the JVP shifted from strict Marxist-Leninist ideology toward a national, framework known as “Jathika Chinthanaya”, while maintaining strong opposition to Indian involvement.

However, it launched a second violent insurgency in 1988–1989, resulting in significant loss of life and severe repression, including the killing of its leader, Rohana Wijeweera. These events marked a decisive turning point, after which the party gradually moved away from armed struggle and embraced parliamentary politics.

By 1994, the JVP abandoned armed insurrection and embraced parliamentary democracy. While retaining its Marxist-Leninist identity, it adopted a more pragmatic socialist approach, seeking influence through elections rather than violence.

Embracing Parliamentary Democracy

The party served as Ministers and Deputy Ministers under President Chandrika Kumaratunga (2004–2005) and later supported Mahinda Rajapaksa in the 2005 presidential and subsequent parliamentary elections. Between 2005 and 2010, the JVP aligned with the Rajapaksa government in opposing federalism and supporting a unitary state.

Historically, the JVP opposed federalism. Under Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD), however, there appears to be a strategic shift toward decentralisation and inclusivity, without formally endorsing federalism. Since 2019, the NPP/JVP has criticised successive governments for failing to implement the 13th Amendment fully. This transformation is real and should be acknowledged.

Reports indicate the NPP/JVP is drafting a new constitution, but there is limited public clarity on its position regarding abolishing the Executive Presidency and devolving powers to Provincial Councils. Sri Lanka can chart a path toward a united, prosperous future where all citizens feel valued and represented. Therefore, I hope that NPP will consider the Provincial Councils in their current form might best serve as a relic of the past, making way for more cohesive and efficient systems of governance.

It is also a fact that many parties have historically criticised the Executive Presidency while in opposition, only to retain it in power. Whether the NPP/JVP will pursue genuine reform remains a subject of debate.

Democratic Concerns State Power

A recent statement by a senior Cabinet Minister that the party holds government power but has not yet “captured” broader state power raises fundamental questions. In a parliamentary democracy, winning government is the highest legitimate authority a party can obtain. Government power is temporary which is granted by voters, limited by the Constitution, and revocable at elections.

State power is permanent and it lies with state institutions i. e. the judiciary, administrative service, armed forces, law enforcement, and independent commissions. These bodies must remain politically neutral and serve the Constitution, to prevent any ruling party from dominating the permanent machinery of governance.

To frame democratic victory as incomplete without “capturing” state power, suggests a conception of power that goes beyond electoral legitimacy. It echoes a revolutionary mindset highlighting the real transformation requires ideological alignment of the state itself.

Past few decades, Sri Lanka has suffered from politicised institutions. Replacing one form of control with another is not reform, it is substitution.

Judiciary and Due Process

Public frustration over past corruption is understandable. However, allegations must be addressed through due legal process. In a democracy, individuals are innocent until proven guilty in a court of law. When parliamentarians publicly pass judgments on opposition figures before judicial proceedings conclude, it risks undermining the rule of law and raising concerns about political overreach.

Concerns are further heightened when there are perceptions that the rule of law is not applied equally, particularly if members of the governing party are treated differently in similar circumstances in the recent past. Unequal enforcement of legal standards can erode public trust in institutions. If such patterns persist, they may raise broader questions about the strength and impartiality of democratic governance.

Village-Level Courts

Democratic Concerns

State Power

In another recent statement, by a senior Minister reiterated one of his earlier proposals to establish judicial courts at the village level to adjudicate certain legal cases, depending on the nature and severity of the alleged offences. While improving local access to justice may enhance efficiency, such courts require strong institutional safeguards.

As this proposal raises serious concerns, it bears characteristics often associated with totalitarian systems, where village-level courts may be controlled by ruling party “cadres” who preside over legal matters and pass judgments against individuals. Without strong safeguards to ensure independence, transparency, and adherence to the rule of law, such courts could be misused to suppress dissent and curtail legitimate political opposition.

Any reform of the judicial system must uphold constitutional protections and preserve the separation of powers. Failing to do so could raise broader concerns about democratic accountability and institutional independence.

Civil / Administrative Service

Before 1978, Sri Lanka’s civil service was widely respected for its professionalism and independence. Over time, however, political appointments increasingly influenced senior administrative positions.

There are growing concerns that some recent appointments to high-level administrative service posts by the NPP may also be politically motivated. Many voters expected systemic reform and a decisive shift toward merit-based governance under the NPP/JVP. It is disappointing to observe indications that similar patterns of politicisation may be continuing.

The real test of reform lies not in rhetoric but in institutional safeguards. Transparent selection criteria, independent oversight mechanisms, and clear accountability structures are essential to ensuring that the administrative service remains professional and non-partisan.

History shows that democracy does not usually collapse overnight. It erodes gradually when ruling parties seek to align permanent institutions with their own ideological or political objectives.

Strengthening institutional independence is not optional, it is imperative. Sri Lanka’s democratic future depends not only on who holds power, but on how responsibly that power is exercised.

Media Freedom

“I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it”

(Evelyn Beatrice Hall, describing Voltaire’s belief in freedom of speech.)

Recent reports suggest the NPP/JVP government is dissatisfied with parts of the media, accusing some outlets of political bias and even proposing bans for allegedly spreading false information. Such actions would be undemocratic and would weaken constructive criticism.

Governments already possess legal remedies for defamation. If laws are inadequate, they may be reviewed. However, this must not undermine the media’s fundamental right to fair, independent, and legitimate criticism of those in power.

Every government dislikes criticism. But mature democracies tolerate it. Any attempt to restrict the media risks eroding democratic freedoms and should be adamantly opposed by all who value an independent media.

Religion and Public Conduct

In the past, opposition parties accused the JVP of being hostile to religion, particularly toward Buddhist monks aligned with political opponents. Confirming this accusation, recently a few NPP/JVP ministers, MPs, and party supporters have publicly criticised Buddhist monks who speak and organise meetings against the government.

At the same time, social media contains intolerable language about the conduct of certain Buddhist monks. While misconduct by members of the clergy is concerning, it does not justify hostile or disrespectful reactions from politicians or the public.

Responding with anger and division contradicts the very Dhamma many claim to defend. Using monks as political tools, or attacking them publicly, only deepens social divisions. If there are genuine concerns about the monastic order, they should be addressed respectfully through proper religious channels rather than through public humiliation.

Economic Democracy

Following Sri Lanka’s 2022 fiscal crisis, the NPP/JVP revised its economic policy and aligned itself with a framework closer to Social Democracy. This shift suggests that the JVP has accepted capitalism as the economic system necessary to revive the collapsed economy. At the same time, it has emphasised redistribution, welfare measures, and regulatory reforms aimed at reducing inequality.

The NPP/JVP’s economic policy now focuses on reforming capitalism rather than replacing it. The party initially sought to renegotiate the IMF agreement to ease the burden on the public. However, it was unable to secure significant changes. A key long-term objective remains reducing dependency on imports. The NPP aims to promote local industries and agriculture, while supporting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to reduce unemployment and expand export capacity.

Although the party pledged to strengthen state-owned enterprises through improved management rather than outright privatisation, recent developments indicate a shift toward public-private partnerships and selective privatisation.

Overall, economic progress is gradually aligning with these reformed Capitalist policies. This approach marks a significant departure from the original “Hammer and Sickle” ideology associated with classical Marxist theory as articulated by thinkers such as Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, and Friedrich Engels.

If judged solely on economic direction, the shift from revolutionary rhetoric to reformist governance appears substantial.

Bribery and Corruption

The nation is deeply grateful to the NPP government for taking bold steps to minimise bribery and corruption, which have long been a cancer eating away at our society. For decades, this practice has existed from top politicians to the lowest levels of the state sector, and even within society at large. Full credit must be given to the NPP government for prioritising the fight against this unethical and deeply rooted problem. It is hoped that the law will be applied equally to everyone, irrespective of status or party affiliation.

However, the public remains sceptical about the delay in pressing charges against the alleged culprits. During the election campaign, the JVP claimed that it possessed substantial evidence, over one hundred files, sufficient to prosecute members of previous governments accused of misusing public funds. Are they now discovering that the evidence is not as concrete as initially suggested?

Conclusion

Having analysed the current situation of the NPP/JVP, it is evident that there are conflicting statements from some senior figures in the JVP. Some favour the continuation of the traditional “Hammer and Sickle” policies. Others within the NPP emphasise and implement aspects of Social Democratic policies. Considering these differences, the nation is entitled to seek clarity regarding the government’s present direction.

It remains to be seen whether the JVP is merely marking time before reintroducing its former ideological policies, or whether it has genuinely chosen the path of Social Democracy.

By Gamini Jayaweera

Features

Valentine’s Day fundraiser … a huge success

In Melbourne, Australia, catering veteran Chris Cannon hosted the annual Valentine’s Day fundraiser at the Springvale RSL, with all proceeds being donated to the Home of Compassion in Sri Lanka, run by the Mother Teresa Sisters.

The Valentine’s Day fundraiser was held on 14 February and the event featured music by Shey and George (of Redemption fame) and DJ Jeremy Ekanayake.

Shey and George providing the entertainment

The international buffet was a spread of Thai specialties and yummy Sri Lankan dishes and the large crowd present enjoyed the setup thoroughly, I’m told.

The lucky winner … trip to Sri Lanka

The Thai Street Food buffet was provided by Chris Cannon’s catering service, with his Thai wife, Annie, doing the needful.

The Cannon Team: Alice, Annie and Chris

His daughter, Alice, also played an active part in this fundraiser.

Chris, a Sri Lankan-born Melbourne resident, who has been hosting this annual event for several years, with all proceeds going to charity, attributes the success of this Valentine’s Day fundraiser to the team that worked tirelessly to make it a happening event.

Rose and a teddy for the ladies

“I’m ever so grateful to the Team that was responsible for the success of this fundraiser. They all worked with enthusiasm and the smiles on their faces, at the end of the event, said it all.”

It was a sell-out, with every lady receiving a rose and a teddy but, unfortunately, said Chris “we had to disappoint several who wanted tickets as it was a limited space venue.”

What’s more, there were also attractive prizes on offer, including a seven nights stay in Sri Lanka.

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction