Features

Culture Shock in Iraq

Part Two PASSIONS OF A GLOBAL HOTELIER

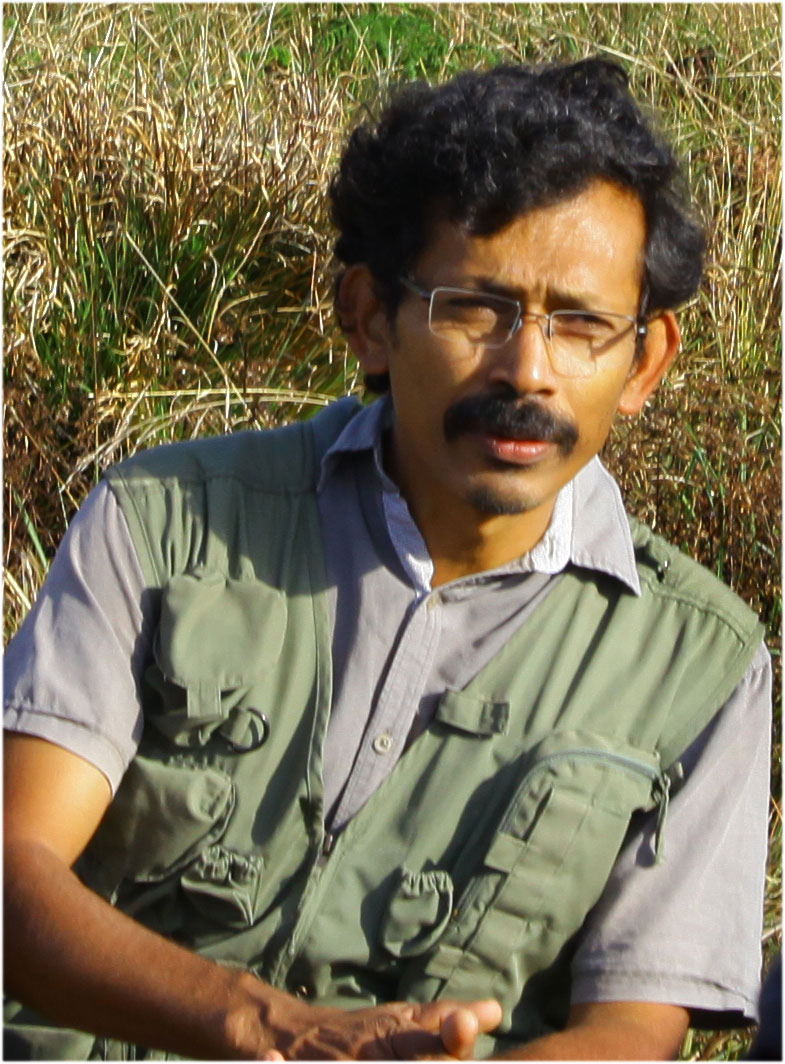

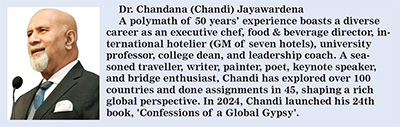

Dr. Chandana (Chandi) Jayawardena DPhil

Dr. Chandana (Chandi) Jayawardena DPhil

President – Chandi J. Associates Inc. Consulting, Canada

Founder & Administrator – Global Hospitality Forum

chandij@sympatico.ca

First Impressions of Iraq

My first impressions of Iraq were positive. Upon arrival at Saddam International Airport, the opulence and modernity juxtaposed against the backdrop of a country rebuilding itself after a war. The warm reception and luxurious accommodations at Hotel Babylon Oberoi spoke volumes about the resilience and hospitality of the Iraqi people. The five-star standards of Hotel Babylon Oberoi, and facilities provided to my family at a corner suite facing Tigris River, were all positive. I was pleasantly surprised as these observations exceeded my expectations.

A tour of Baghdad for new managers of Hotel Babylon Oberoi arriving from Sri Lanka, during our second day, produced more pleasant surprises. A string of five-star hotels in Baghdad, managed by global hotel chains such as Sheraton, Le Meridien, Melia and Novotel, provided competition for Oberoi. Although wars always affect tourism negatively, wars also contribute to hotel revenues with new customers as military advisers from other countries, arm dealers, spies, mercenaries, international agencies, media representatives, reporters, journalists, etc. We were pleased to note that the best hotel in Baghdad was the 450-room Al Rasheed, and the best hotel outside Baghdad was the Nineveh Oberoi Hotel, a 262-room, five-star resort in Mosul overlooking the Tigris River. Both Al Rasheed and Nineveh Oberoi, were sister hotels of Hotel Babylon Oberoi.

The emergence of Iraq’s tourism and hospitality scene, with a plethora of international hotel chains vying for prominence, painted a picture of economic revitalization amidst the remnants of war. The three Oberoi hotels in Iraq managed a total of over 1,000 five-star rooms and Oberoi was the key player in re-building tourism in the post-war Iraq in 1989. Madan Misra, my boss, and the Oberoi Group (operator of 30 luxury hotels in six countries, with head office in New Delhi, India, founded in 1934), had good connections with the Iraqi government and the State Organization for Tourism in Iraq, which owned all hotels in the country.

Two of my Ceylon Hotel School colleagues, senior to me, worked at Al Rasheed. Nirmo Thambapillai was the Food & Beverage Manager for Banquet Operation, and Kamal Hapuwatte was the Training Manager. Another friend of mine (whom I met during an assignment at Muscat Sheraton in Oman in 1988 as the Guest Executive Chef for a Sri Lankan food festival), Priyantha Ratnasinghe, was the Assistant Financial Controller at Baghdad Sheraton. The camaraderie among colleagues from Sri Lanka added a comforting familiarity in an unfamiliar land. We met frequently during our free time.

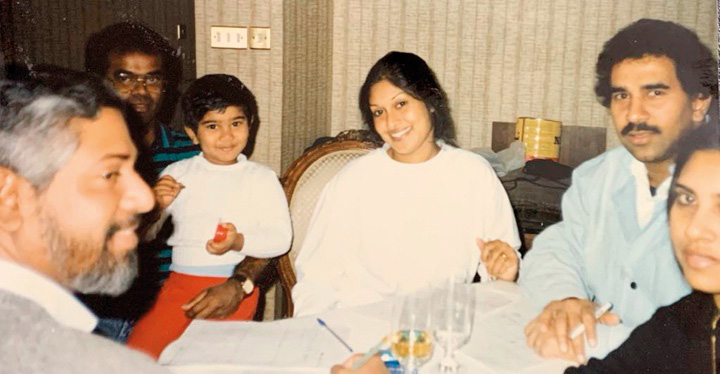

When my wife and son joined me, they were warmly welcomed by everybody. My son, Marlon was only three years old and was the only child staying at the hotel. After he commenced going to the international school in Baghdad, every day when he returned from school, the staff inquired what he had learned. They often addressed Marlon and me as ‘Habibi’ (my dear or darling) and my wife as ‘Ainee’ (my eyes).

We soon realised that this type of loving terms are common in addressing each other in Iraq. People in Iraq are among the friendliest I have met during my travels to one hundred countries. After each welcoming handshake, most Iraqi men touched their chest expressing that the greetings came from heart. I loved that gesture so much, I practiced that from the time I settled down in Iraq, and in later years whenever I travelled to the Middle East for work and leisure.

The cultural diversity within Iraq, from the majority traditional Islamic customs to the cosmopolitan Christian communities, offered a multifaceted glimpse into the nation’s identity. Islam (approximately 55% Shia and 35% Sunni) was and still is the main religion in Iraq, and there was a Kurdish minority following the ancient religion Zoroastrianism. In 1989 most of the 1.5 million Christians (around 9% of the population) in Iraq lived in or around Baghdad.

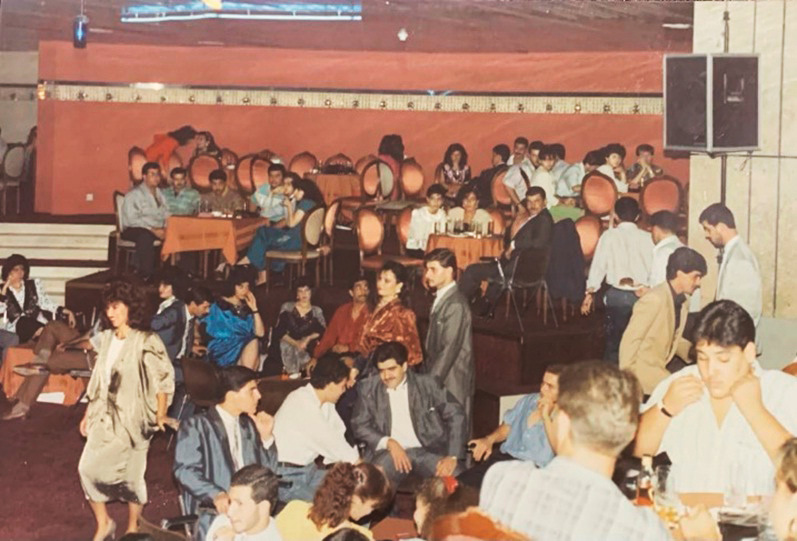

They were far more westernized than other Iraqis. The Christian Iraqis generally provided good business to restaurants, bars, night clubs and casinos in Baghdad. The end of the war was also a period of celebration and enjoyment. It was good for the hotel and food and beverage businesses. I was surprised to see many beautiful Iraqi women dressed in western clothes and patronising the bars, night club and casino at Hotel Babylon Oberoi. Unfortunately, the Christian population in Iraq has shrunk to 1% of the current total national population of 47 million in 2024.

Navigating Challenges

The transition from initial optimism to navigating cultural nuances brought forth unexpected challenges and a string of culture shocks in Iraq. From adapting to the ubiquity of firearms, to learning the rhythm of work interrupted by prayer times, each obstacle became a lesson in understanding and respect. I treated these challenges as opportunities to learn the local attitudes, aspirations, behaviour, beliefs, customs, and culture.

Violation of ‘No-Gun Policy’

A major culture shock for us was getting used to the fact that most men in Iraq openly carried firearms. During my orientation week, I was taken around Babylon Oberoi by Mohamed Abdullah, the Iraqi Human Resources Manager, and T. P. Singh (TP), Indian Assistant Food & Beverage Manager, who was my deputy. On seeing hundreds of numbered pigeon holes at the entrance to Githara Night Club, I inquired what they wee used for. “Acha! Mr. Jayawardena, those are for carefully storing surrendered guns by our patrons, until they leave the night club. As Iraqis have a habit of shooting their guns at air in celebration when happy and drunk, we have a no-gun policy at Githara,” TP explained. “We don’t want them to destroy our expensive Baccarat chandeliers imported from France,” he added with a cheeky smile.

When I asked him, “Do all our customers adhere to hotel’s no-gun policy at the night club?” he was honest in his answer: “All but one group – President Saddam Hussein’s eldest son Uday and his gang of murderous bodyguards, who come to Githara every Thursday night!” That warning reminded me that I was assigned the role of the duty manager every Thursday night till Githara closed around 4:00 am or until Uday Hussein was ready to leave.

Over-boiling in Kitchens

During my orientation in the kitchens, I was somewhat taken back to notice some kitchen staff not bothering to reduce flames in the hot kitchen during the prayer times. More religious employees simply stop work, irrespective of the stage of their cooking tasks, when the bells rang in the nearby mosques. It was an unwritten law that no one should give work directions to employees praying for 10 to 15 minutes at a time. Non-Islamic members of the kitchen brigade, diplomatically reduced fires gently to ensure there was no over-boiling and over-cooking during the prayer times. I quickly got used to that custom. It is essential that expatriates understand, accept, and respect local customs and culture, particularly relating to religion. They must also quickly learn to ensure that there are no interruptions to the flow of work and quality of products and services.

Being Kissed by Men

During my orientation, there was an important wedding at the hotel’s ballroom. The bride’s father was a minister in President Saddam Hussein’s cabinet, and we wanted to ensure that everything was handled exactly as requested by the minister. I showed up a few times at the banquet hall during thereception. Out of 500 invitees, about half were beautifully dressed women who all sat on one half of the hall. When they made a frequent loud and long, wavering, high-pitched vocal sound, I was baffled. Our Egyptian Banquet Manager, Altaf, realizing that it was a new experience for me, said: “Boss, that’s zaghārīt, an ululation to honour the new couple.”

The other half of the hall was occupied by males, most of whom smoked, and held a Misbaha (a string of 99 beads traditionally used during prayer). When the minister saw me he was in a happy mood. He hugged me and gave four kisses on my cheeks. I nearly pushed him away, but when Altaf quickly gestured me to reciprocate, I hugged the minister in return. After learning that men hugging each other is common in Iraq, I too became an expert at it. Understanding the importance of cultural sensitivity and adaptation is a key for success in a global career.

Removal of Saddam’s Twin Photograph

I was given a large office. My secretary was Fatima, a very polite young Iraqi lady with an office next to mine. My first impression of my office was that everything except my desk and chair were green, and there were two large, identical, black and white framed photographs of Saddam Hussein hung on two walls. I politely suggested: “Fatima, do you mind transferring one of these photos of His Excellency to another executive office?”

The rest of the day, I could not locate Fatima. She eventually returned after several hours later looking nervous and pale, and was speechless. When I inquired what happened to her, she signalled me to come out of the office, and whispered to me, “Mr. Jay, removal of a photograph of the President will be reported to the Baath party head office as a major insult and there will be serious repercussions to both you and me.” I immediately changed my mind and requested Fatima to forget about my suggestion and not to mention it to anyone. During my turn in Baghdad, every day I looked at those two large photographs. I got used to it and realised that Sadam Hussein was a handsome man.

Wire Tapped Offices

There were rumours among other expatriate managers that all our offices were wire tapped. On hearing that any discussion in any executive office of a hotel can be heard at the Baath party head office, I laughed saying that it can’t be true. However, I decided to be extra careful in the future. The undercurrent of surveillance and espionage added an element of intrigue to daily life, with the realization that conversations held within the confines of our offices might not be as private as initially assumed.

Spies at Apartments

When I asked TP about various plainclothed men keeping a close eye on hotel activities, but not acting as customers, I was surprised of his answer. “Acha! Mr. Jayawardena, those are secret police and at times, spies,” TP said in a relaxed tone. He had been in Iraq for a few years and knew the ropes. When I asked him whom they spy on, he said, “Us, the foreign managers.” Then he became a bit jovial, tapped on my shoulder in a friendly gesture, and said: “welcome to Baghdad, Mr. Jayawardena!” Soon I realised that there were spies everywhere. No one knew who was spying on whom. This was common in most countries led by iron-fisted dictators. The subtle yet persistent presence of secret police underscored the complexities of operating in a society under scrutiny.

Every week, Friday was my off day. Usually on Fridays my family went on full day outings or visited the Hapuwatte family living at the executive quarters of Al Rasheed Hotel. At their apartment we played cards, had a couple of drinks, had a home-cooked Sri Lankan meal, and spoke about our memorable Ceylon Hotel School years. On the first Friday we went out, when we returned, my wife said “Someone has been in our suite.

The books and magazines we left on the coffee table have been re-arranged! Can’t be housekeeping staff, as I have told them not to do cleaning work on Fridays.” On checking with the General Manager’s wife, we found out that it was the normal practice for Iraqi secret police to visit expatriate manager’s apartments when they are away and leave some clues to show us that they have visited! When my wife was upset about it, I told her: “Shani, don’t worry, unless we lost any of our belongings. When in Rome, do as the Romans do.”

Initial Optimism and Challenge in Iraq

Despite these challenges, I commenced my work optimistically. My senior team leaders in the food & beverage division agreed with me to organize regular food festivals, open new restaurants with exciting new menus, and do lots of training. I was able to motivate the team and win the support of our regular customers.

The collaborative spirit and innovative mindset fostered a sense of unity and purpose amidst uncertainty. Executive Chef O. P. Khantwal (OP) became my right-hand man while implementing our innovations for a new era. OP was a well-trained senior chef of the Oberoi Group and the first chef I worked with who had an MA degree qualification. OP knew the Oberoi culture very well and soon became a loyal advisor to me.

was a well-trained senior chef of the Oberoi Group and the first chef I worked with who had an MA degree qualification. OP knew the Oberoi culture very well and soon became a loyal advisor to me.

As my team was settling down and developing our new business plans, we were faced with a shocker. The bureaucracy and red tape in Iraq resulted in delays of the work permit process for new workers. We were asked by authorities to stop work until all work permit final approvals are received. As a result, we spent two unproductive weeks, without working. I decided to use that challenge as an opportunity to explore Iraq as a tourist.

Features

Challenges to addressing allegations during Sri Lanka’s armed conflict

A political commentator has attributed the UK sanctions against four individuals, three of whom were top ranking Army and Navy Officers associated with Sri Lanka’s armed conflict, to the failure of successive governments to address human rights allegations, which he describes as a self-inflicted crisis. The reason for such international action is the consistent failure of governments to conduct independent and credible inquiries into allegations of war crimes; no ‘effective investigative mechanism’ has been established to examine the conduct of either the Sri Lankan military or the LTTE.

He has not elaborated on what constitutes an “effective investigative mechanism. He has an obligation and responsibility to present the framework of such a mechanism. The hard reality however is that no country, not even South Africa, has crafted an effective investigative mechanism to address post conflict issues.

INVESTIGATIVE MECHANISMS

The hallmark of a credible investigative mechanism should be unravelling the TRUTH. No country has ventured to propose how such a Mechanism should be structured and what its mandate should be. Furthermore, despite the fact that no country has succeeded in setting up a credible truth-seeking mechanism, the incumbent government continues to be committed to explore “the contours of a strong truth and reconciliation framework” undaunted by the failed experiences of others, the most prominent being South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is often cited as the gold standard for post conflict Mechanisms. Consequently, most titles incorporate the word “Truth” notwithstanding the fact that establishing the “Truth” was a failure not only in South Africa but also in most countries that attempted such exercises.

Citing the South African experience, Prof. G. L. Peiris states: “pride of place was given to sincere truth-telling which would overcome hatred and the primordial instinct for revenge. The vehicle for this was amnesty…… Despite the personal intervention of Mandela, former State President P. W. Botha was adamant in his refusal to appear before the Commission, which he deemed as ‘a fierce unforgiving assault’ on Afrikaaners” (The Island, 01 April, 2025). In the case of Sri Lanka too, disclosures to find the “Truth” would be all about the other party to the conflict, thus making Truth seeking an accusatory process, instead of a commitment to finding the Truth. The reluctance to engage in frank disclosure is compounded by the fear of recrimination by those affected by the Truth.

Continuing Prof. Peiris cites experiences in other countries. “Argentina, the power to grant amnesty was withheld from the Commission. In Columbia, disclosure resulted not in total exoneration, but in mitigating sentences. In Chile, prosecutions were feasible only after a prolonged interval since the dismantling of Augusta Pinochet’s dictatorship ….” (Ibid).

The mechanisms adopted by the countries cited above reflect their own social and cultural values. Therefore, Sri Lanka too has to craft mechanisms in keeping with its own civilisational values of restorative and not retributive justice for true reconciliation, as declared by President J. R, Jayewardene in San Francisco as to what the global attitude should be towards Japan at the conclusion of World War II. Since the several Presidential Commissions appointed under governments already embody records of alleged violations committed, the information in these commission reports should be the foundation of the archival records on which the edifice of reconciliation should be built.

ESTABLISHING DUE CONTEXT

The suggestion that an independent and credible inquiry be conducted into allegations of war crimes reflects a skewed understanding of the actual context in which the armed conflict in Sri Lanka occurred. Even the UNHRC has acknowledged that the provisions of “Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions relating to conflicts not of an international character is applicable to the situation in Sri Lanka, as stated in para. 182 of the OISL Report by the UNHRC Office. Therefore, the correct context is International Humanitarian Law with appropriate derogations of Human Rights law during an officially declared Emergency as per the ICCPR.; a fact acknowledged in the OISL report.

Consequently, the armed conflict has to conform to provisions of Additional Protocol II of 1977, because “This Protocol, which develops and supplements Article 3 common to the Geneva Conventions is the due context. There is no provision for “alleged war crimes” in the Additional Protocol. Although Sri Lanka has not formally ratified Additional Protocol II, the Protocol is today accepted by the Community of Nations as Customary Law. On the other hand, “war crimes” are listed in the Rome Statute; a Statute that Sri Lanka has NOT ratified and not recognized as part of Customary Law.

Therefore, any “investigative mechanism” has to be conducted within the context cited above, which is Additional Protocol II of 1977.

SRI LANKAN EXPERIENCE

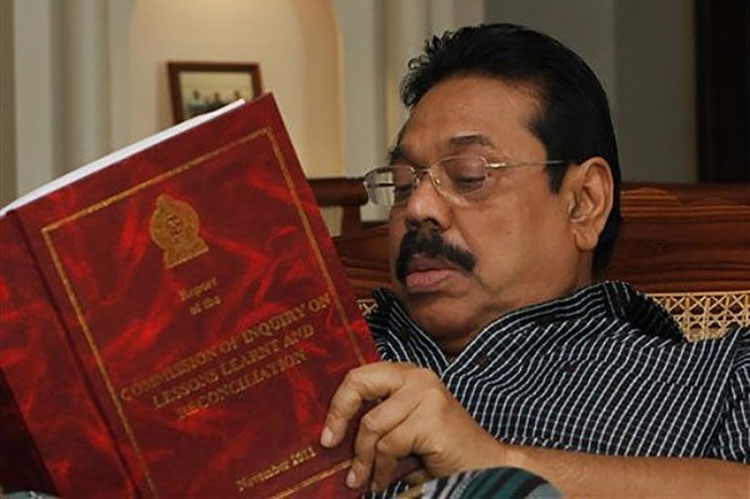

On the other hand, why would there be a need for Sri Lanka to engage in an independent and credible inquiry into allegations, considering the following comment in Paragraph 9.4 and other Paragraphs of the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC)?

“In evaluating the Sri Lankan experience in the context of allegations of violations of IHL (International Humanitarian Law), the Commission is satisfied that the military strategy that was adopted to secure the LTTE held areas was one that was carefully conceived in which the protection of the civilian population was given the highest priority”

9.7 “Having reached the above conclusion, it is also incumbent on the Commission to consider the question, while there is no deliberate targeting of civilians by the Security Forces, whether the action of the Security Forces of returning fire into the NFZs was excessive in the context of the Principle of Proportionality…” (Ibid)

The single most significant factor that contributed to violations was the taking of Civilians in the N Fire Zone hostage (NFZ) by the LTTE. This deliberate act where distinction between civilian and combatant was deliberately abandoned, exposed and compromised the security of the Civilians. The consequences of this single act prevent addressing whether military responses were proportionate or excessive, or whether the impact of firing at make-shift hospitals were deliberate or not, and whether limiting humanitarian aid was intentional or not. These issues are recorded and addressed in the Presidential Commission Reports such as LLRC and Paranagama. This material should be treated as archival material on which to build an effective framework to foster reconciliation.

UK SANCTIONS

Sanctions imposed by the UK government as part of an election pledge for Human Rights violations during the armed conflict is a direct act of intervention according to Article 3 of the Additional Protocol of 1977 that is the acknowledged context in which actions should be judged.

Article 3 Non-intervention states:

1 “Nothing in the Protocol shall be invoked for the purpose of affecting the sovereignty of a State or the responsibility of the government by all legislative means, to maintain or re-establish law and order in the State or to defend the national unity and territorial integrity of the State”.

2 “Nothing in the Protocol shall be invoked as a justification for intervening directly or indirectly, for any reason whatsoever, in the armed conflict or in the internal or external affairs of the High Contracting Party in the territory on which the conflict occurs”.

Targeting specific individuals associated with the armed conflict in Sri Lanka is a direct assault of intervention in the internal affairs of Sri Lanka. The UK government should be ashamed for resorting to violating International Law for the sake of fulfilling an election pledge. If Sri Lanka had issued strictures on the UK government for not taking action against any military officers responsible for the Bloody Sunday massacre where 26 unarmed civilians participating in a protest march were shot in broad daylight, Sri Lanka would, in fact be intervening in UK’s internal affairs.

CONCLUSION

The UK’s action reflects the common practice of making election pledges to garner targeted votes of ethnic diasporas. The influence of ethnic diasporas affecting the conduct of mainstream politics is becoming increasingly visible, the most recent being the Tamil Genocide Education Week Act of Ontario that was dismissed by the Supreme Court of Canada on grounds the Provincial Legislations have no jurisdiction over Federal and International Laws.

However, what should not be overlooked is that the armed conflict occurred under provisions of common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions. This Article is developed and supplemented by Additional Protocol II of 1977. Therefore, since all Geneva Conventions are recognised as Customary Law, so should the Additional Protocol II be, because it is a development of common Article 3.

Imposing sanctions under provisions of Additional Protocol II amounts to Intervention in internal affairs of a State as stated in Article 3 of the Protocol; II cited above. Such interventions are prohibited under provisions of international law.

The need to revive independent and credible inquiries after the lapse of 16 years is unrealistic because those who were perpetrators and victims alike cannot be identified and/or located. Furthermore, the cost of disclosure because of the possibility of retribution would compromise their security. A realistic approach is to use the material recorded in the Presidential Commission Reports and treat them as archival records and use the lessons learnt from them to forge a workable framework that would foster unity and reconciliation with the survivors in all communities This is not to live in the past but to live in the here and now – the present, which incidentally, is the bedrock of Sri Lanka’s civilisational values.

by Neville Ladduwahetty

Features

The Silent Invasion: Unchecked spread of oil palm in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s agricultural landscape is witnessing a silent yet profound transformation with the rapid expansion of oil palm plantations. Once introduced as a commercial crop, the oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) is now at the center of a heated debate, with environmentalists and scientists warning of its devastating ecological consequences.

Speaking to The Island research scientist Rajika Gamage, said: “The spread of oil palm in Sri Lanka is not just a concern for biodiversity, but also for water resources, soil stability, and even local economies that rely on traditional crops.”

A Brief History of Oil Palm Cultivation

Oil palm, originally from West and Central Africa, was first cultivated for commercial purposes in Java in 1948 by Dutch colonists. It reached Malaysia and Indonesia by 1910, where its lucrative potential drove large-scale plantations.

According to Gamage, in Sri Lanka, the first significant oil palm plantation was established in 1968 at Nakiyadeniya Estate by European planters, initially covering a mere 0.5 hectares. Today, oil palm cultivation is predominantly concentrated in Galle, Matara, and Kalutara districts, with smaller plantations in Colombo, Rathnapura, and Kegalle.

Over the decades, he says the commercial viability of oil palm has prompted its expansion, often at the cost of native forests and traditional agricultural lands. Government incentives and private investments have further accelerated the spread of plantations, despite growing concerns over their environmental and social impacts.

Economic Boon or Environmental Curse?

Supporters of oil palm industry argue that it is the most efficient crop for vegetable oil production, yielding more oil per hectare than any other alternative. Sri Lanka currently imports a significant amount of palm oil, and expanding local production is seen as a way to reduce dependence on imports and boost local industries. However, Gamage highlights the hidden costs: “Oil palm plantations deplete water sources, contribute to soil erosion, and threaten native flora and fauna. These are long-term damages that far outweigh the short-term economic benefits.”

One of the primary environmental concerns is the aggressive water consumption of oil palm, which leads to the depletion of underground aquifers. This is particularly evident in areas such as Kalu River and Kelani River wetlands, where native ecosystems are being severely affected. Additionally, soil degradation caused by extensive monoculture farming results in loss of fertility and increased vulnerability to landslides in hilly regions.

Furthermore, studies show that oil palm plantations disrupt the natural habitats of endemic species. “Unlike rubber and coconut, oil palm does not support Sri Lanka’s rich biodiversity. It alters the soil composition and prevents the regeneration of native plant species,” Gamage explains. The loss of forest cover also exacerbates human-wildlife conflicts, as displaced animals venture into human settlements in search of food and shelter.

A Threat to Indigenous Agriculture and Culture

Beyond environmental concerns, oil palm is also threatening traditional crops like kitul (Caryota urens) and palmyrah (Borassus flabellifer), both of which hold economic and cultural significance. “These native palms have sustained rural livelihoods for centuries,” says Gamage. “Their gradual replacement by oil palm could lead to economic instability for small-scale farmers.”

Kitul tapping, an age-old tradition in Sri Lanka, provides a source of income for thousands of families, particularly in rural areas. The syrup extracted from kitul is used in local cuisine and traditional medicine. Similarly, palmyrah has deep roots in Sri Lankan culture, particularly in the Northern and Eastern provinces, where its products contribute to food security and local industries.

The rise of oil palm plantations has led to the clearing of lands that once supported the traditional crops. With large-scale commercial investments driving oil palm expansion, small-scale farmers are finding it increasingly difficult to sustain their livelihoods. Gamage warns, “If we allow oil palm to replace our native palms, we risk losing not just biodiversity, but also a vital part of our cultural heritage.”

The Global Perspective: Lessons from Other Nations

Sri Lanka is not the first country to grapple with the consequences of oil palm expansion. Malaysia and Indonesia, the world’s leading producers of palm oil, have faced severe deforestation, biodiversity loss, and socio-economic conflicts due to unchecked plantation growth.

In Indonesia, for example, vast tracts of rainforest have been cleared for palm oil production, leading to habitat destruction for endangered species such as orangutans and Sumatran tigers. Additionally, indigenous communities have been displaced, sparking legal battles over land rights.

Malaysia has attempted to address some of these issues by introducing sustainability certifications, such as the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) standard. However, implementation challenges remain, and deforestation continues at an alarming rate.

Sri Lanka can learn valuable lessons from these experiences. Implementing strict land-use policies, promoting agroforestry practices, and ensuring transparency in plantation expansion are crucial steps in mitigating environmental damage while supporting economic development.

The Urgent Need for Action

Despite these concerns, Sri Lanka has yet to enforce strict regulations on oil palm expansion. Gamage urges authorities to intervene: “It is imperative that we implement policies to control its spread before it is too late. The unchecked expansion of oil palm will lead to irreversible environmental damage.”

To address this issue, experts suggest a multi-pronged approach:

Stronger Land-Use Policies

– The government must enforce restrictions on oil palm cultivation in ecologically sensitive areas, such as wetlands and forest reserves.

Reforestation and Rehabilitation

– Efforts should be made to restore degraded lands by reintroducing native tree species and promoting sustainable agroforestry.

Supporting Traditional Agriculture

– Incentives should be provided to farmers growing traditional crops like kitul and palmyrah, ensuring that these industries remain viable.

Public Awareness and Education

– Raising awareness among local communities about the environmental and social impacts of oil palm can empower them to make informed decisions about land use.

Sustainable Alternatives

– Encouraging research into alternative vegetable oil sources, such as coconut oil, which has long been a staple in Sri Lankan agriculture, could reduce reliance on palm oil.

As Sri Lanka stands at a crossroads, the decisions made today will determine the country’s ecological and agricultural future. While the economic benefits of oil palm are undeniable, its long-term environmental and social costs cannot be ignored. The challenge now is to strike a balance between economic growth and environmental sustainability before the damage becomes irreversible.

In conclusion Gamage said, “We must act now. If we allow oil palm to spread unchecked, future generations will bear the cost of our inaction.”

Sri Lanka has the opportunity to take a different path—one that prioritises biodiversity conservation, sustainable agriculture, and the well-being of local communities. The time for decisive action is now.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

A plea for establishing a transboundary Blue-Green Biosphere Reserve in Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay

Blue-green land and waterscapes act as ecological corridors across land and water in creating an ecological continuity in order to protect and restore the habitats of native and naturalised species.

In addition, these ecological corridors also help to conserve and improve the habitats of migratory species, as well. One of the main objectives of establishing blue-green land-waterscapes is to reconcile increasing local/regional development and human livelihood challenges in a sustainable manner while, at the same time, safeguard biodiversity and their habitats/ecosystems, as far as possible.

While green landscapes are natural and semi-natural terrestrial vegetation types like natural forests and grasslands, blue waterscapes are aquatic or semi-aquatic vegetation types such as seagrass meadows, mangroves and coastal and other wetlands. These vegetated coastal ecosystems known as ‘blue carbon’ ecosystems are some of the most productive on Earth and located at the interfaces among terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments. They provide us with essential ecosystem services, such as serving as a buffer in coastal protection from storms and erosion, spawning grounds for fish, filtering pollutants and contaminants from coastal waters thus improving coastal water quality and contributing to all important food security.

In addition, they capture and store “blue” carbon from the atmosphere and oceans at significantly higher rates per unit area than tropical forests (Figure 1) and hence act as effective carbon sinks. By storing carbon, these ecosystems help to reduce the amount of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, thus contributing significantly to mitigate the effects of climate change.

Figure 1: Carbon storage in different vegetation types (Source – What Is Blue Carbon and Why Does It Matter? – Sustainable Travel International)

.Blue-green Carbon Markets

The recognition of blue carbon (BC) ecosystems (primarily mangroves, seagrasses and tidal marshes) as an effective natural climate solution paved the way for their inclusion within carbon markets. Blue carbon is the marine analog of green carbon, which refers to carbon captured by terrestrial (i.e., land-based) plants. The blue-green carbon market involves buying and selling carbon credits from projects that protect and restore coastal and marine ecosystems (blue carbon) and terrestrial ecosystems (green carbon). Since Blue Carbon ecosystems have higher carbon sequestration (capture and store) potential compared to their terrestrial counterparts, blue Carbon credits are worth over two times more than green carbon credits. They offer opportunities for commercial enterprises to offset carbon emissions and in turn support climate action.

Blue Carbon projects are expected to grow twofold in the near future. With the recent surge in international partnerships and funding, there is immense growth potential for the blue carbon market. However, it is critically important to look beyond the value of the carbon sequestered to ensure the rights and needs of local communities that are central to any attempt to mitigate climate change using a blue and green carbon project.

Blue Carbon projects can serve as grassroot hubs for sustainable development by developing nature-based solutions in these ecosystems thus contributing to both climate change mitigation and adaptation. Globally, numerous policies, coastal management strategies, and tools designed for conserving and restoring coastal ecosystems have been developed and implemented. Policies and finance mechanisms being developed for climate change mitigation may offer an additional route for effective coastal management. The International Blue Carbon Initiative, for example, is a coordinated, global program focused on conserving and restoring coastal ecosystems for the climate, biodiversity and human wellbeing.

Until recently, most of these opportunities focus on carbon found in the above ground vegetative biomass and do not account for the carbon in the soil. On the other hand, blue carbon, in particular has the potential for immense growth in carbon capture economics in the near future and can provide significant socioeconomic and environmental benefits. Consequently, blue -green carbon habitats in the Gulf of Mannar – Palk Bay region represent invaluable assets in climate change mitigation and coastal ecosystem conservation and sustainable development.

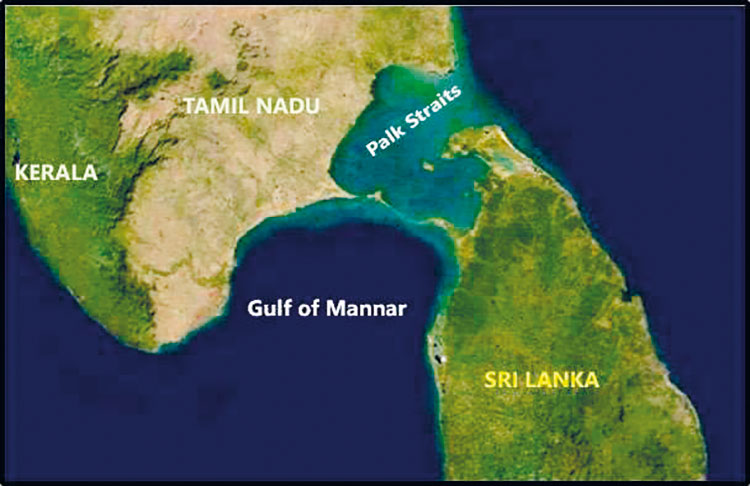

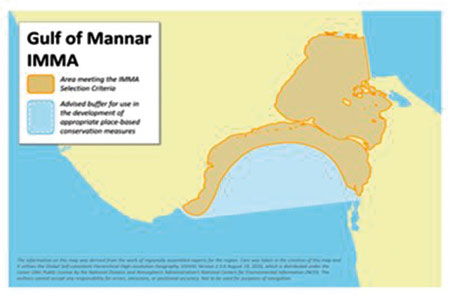

Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay Trans-boundary Region

The Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay region form a transboundary area within the waters of southeastern India and northwestern Sri Lanka. This region supports dense seagrass meadows having a high level of marine biodiversity including marine mammals such as dugong. Sea turtles are frequent visitors to the gulf while sharks, dolphins, sperm and baleen whales too, have been reported from this area. The Mannar region is recognized as an Important Marine Mammal Area (IMMA) of the world by IUCN (Figure 2) and also an Important Bird Area by Birdlife International. This region as a whole is a store house of unique biological wealth of global significance and as such is considered as one of the world’s richest regions from a marine biodiversity perspective.

Figure 2. Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay IMMA (Source – IUCN Joint SSC/WCPA Marine Mammal Protected Areas Task Force, 2022 IUCN-MMPATF (2022)

Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve – India

India has already declared a part of this region as the UNESCO Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve covering an area of 10,500 km2 of ocean with 21 islands and the adjoining coastline. The islets and coastal buffer zone include beaches, estuaries, and tropical dry broadleaf forests, while the surrounding seascape of the Marine National Park (established in 1986) and a 10 km strip of the coastal landscape that include seaweed communities, seagrass communities, coral reefs, salt marshes and mangrove forests form the coastal and marine component of the biosphere reserve on the Indian side of the Gulf of Mannar.

Sri Lankan ‘Proposed’ Biosphere Reserve

On the Sri Lankan side of the Palk Bay there is a semi-enclosed shallow water body between the southeast coast of India and Sri Lanka, with a water depth maximum of 13 m. To the south, a chain of low islands and reefs known as Adam’s Bridge or Rama Setu (Rama’s Bridge), separates Palk Bay from the Gulf of Mannar. The Palk Bay leads to Palk Strait (Figure 3). Palk Bay is one of the major sinks for sediments along with the Gulf of Mannar. Sediments discharged by rivers and transported by the surf currents as littoral drift settle in this sink.

On the Sri Lankan side of the Palk Bay, studies are being conducted by the Dugong and Seagrass Conservation Project to establish an additional 10,000 hectares of Marine Protected Area to support the conservation of dugongs and their seagrass habitat in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay. This project will involve the preparation of a multiple-community-based management plan in conjunction with government, fishing communities and the tourism industry.

With this valuable information emerging from projects of this nature, Sri Lanka has real opportunities to create a large marine protected area in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay region and eventually merging them together with the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve of India to form a trans-boundary biosphere Reserve.

Terrestrial cum Marine Spatial Plan for the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay Region

Therefore, an excellent opportunity awaits both the Governments of Sri Lanka and India to collaborate in preparing of a terrestrial and marine spatial plan for this region, a prerequisite before going further on designing and implementing large scale development plans in establishing wind energy farms, mineral sand extraction, fishing industry, oil exploration and tourism development.

Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning (CMSP) is an integrated, place-based approach for allocating coastal and marine resources and space, while protecting the ecosystems that provide these vital resources.

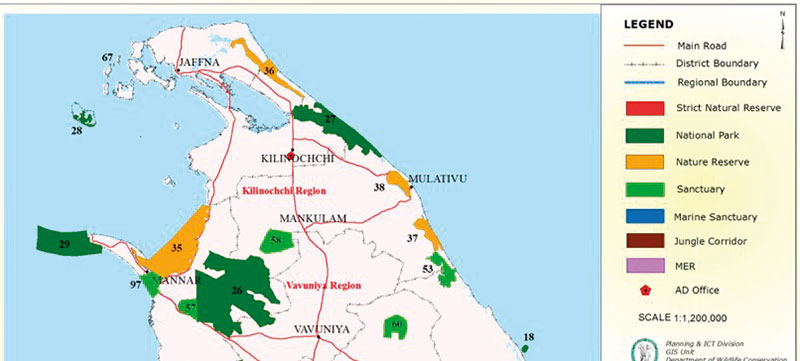

On the Indian side, the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere reserve is well established and functional. On the Sri Lankan side, already there are three DWLC managed protected areas i) Adam’s Bridge Marine National Park (# 29 in the map – 18,990 ha declared in 2015), ii) Vedithalathiv Nature Reserve (# 35 -29,180 ha declared in 2016) and iii) Vankalai Sanctuary ( # 97 -4839 ha declared in 2008) (Figure 4) which can serve as the core zone of the Sri Lankan counterpart of a trans-boundary biosphere reserve. Due to the integrated nature of shallow wetland and terrestrial coastal habitats, Vankalai Sanctuary, in particular is highly productive, supporting high ecosystem and species diversity.

Figure 4: Protected Areas in Norther Sri Lanka Managed by the Department of Wildlife Conservation Source: DWLC

This site provides excellent feeding and living habitats for a large number of water bird species, including annual migrants, which also use this area on arrival and during their exit from Sri Lanka.

Having several coastal and marine protected areas already within the Sri Lankan territory provide an excellent opportunity to establish the Gulf of Mannar – Palk Bay blue-green Biosphere Reserve (Sri Lanka) initially and eventually to join up seamlessly with the already established Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve on the Indian side to create a trans-boundary blue-green biosphere reserve.

This makes perfect sense because unlike sedentary plant species, mobile animal and plant groups (phytoplankton, in particular) do not respect human demarcated territorial boundaries. The provision of a common and unhindered protected coastal and marine passage for their customary movement for food and raising young is therefore of crucial importance in conservation management. Scientific evidence-based selection of additional areas, if necessary and their respective boundaries are best be determined in consultation with expert groups on marine mammals and reptiles, birds, fish, coastal vegetation conservation, sociology and industrial development from both sides of the divide.

Proper spatial planning needs to be done before large-scale development plans are designed and implemented in order to avoid conflicts of interest leading to inordinate delays and teething problems in project initiation. As a priority, the protected blue-green core and buffer regions need to be demarcated for their conservation. This could best be done in this narrow passage of land and water between Sri Lanka and India

( Palk Strait & Gulf of Mannar) by preparing a marine and terrestrial spatial plan along the UNESCO Man and Biosphere conceptual guidelines differentiating core, buffer and transition zones. While the protected areas in the core and buffer zone provide all important ecosystem services that would also serve as breeding ground for fish, crustaceans, marine reptiles, birds and mammals thereby provisioning sustainable industries to be developed in the surrounding transition areas demarcated in the joint spatial plan.

In addition, the Satoyama Global Initiative established by the Japanese at UNESCO as a global effort in 2009 to realise ‘societies in harmony with nature’ in which – Satoumi – specifically referring to the management of socio-ecological production landscapes in marine and coastal regions, is also a good model to be considered for conservation of biodiversity and co-existence between humans and nature.

Final Plea

In order to take this proposal forward from the Sri Lankan side, a number of useful baseline reports are already available including, but not limited to, the following: i. Biodiversity Profile of the Mannar District (CEJ & USAID 2022), ii. The Gulf of Mannar and its surroundings (IUCN 2012), iii) Atlas of Mangroves, Salt Marshes and Sand Dunes of the Coastal Area from Malwathu Oya to Pooneryn in the Northwestern Coastal Region, Sri Lanka (Ecological Association of Sri Lanka, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka, 2020). iv. Integrated Strategic Environment Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka (CEA 2014).

If this proposal to establish a Trans-boundary Blue-Green Biosphere Reserve in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay is acceptable in principle to the Governments of Sri Lanka and India, it would be ideal if the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) program UNESCO which is an intergovernmental scientific program whose mission is to establish a scientific basis for enhancing the relationship between people and their environments to partner with the relevant Government and non-governmental agencies in both countries in making it a reality. This proposed concept has all the necessary elements for developing a unique sustainable conservation cum industrial development strategy via nature-based solutions while at the same time contributing to both climate change mitigation and adaptation.

by Emeritus Professor Nimal Gunatilleke,

University of Peradeniya

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoBid to include genocide allegation against Sri Lanka in Canada’s school curriculum thwarted

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoSri Lanka’s eternal search for the elusive all-rounder

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoGnanasara Thera urged to reveal masterminds behind Easter Sunday terror attacks

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoTo play or not to play is Richmond’s decision

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoComBank crowned Global Finance Best SME Bank in Sri Lanka for 3rd successive year

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoSanctions by The Unpunished

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoMore parliamentary giants I was privileged to know

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoIPL 2025: Rookies Ashwani and Rickelton lead Mumbai Indians to first win