Features

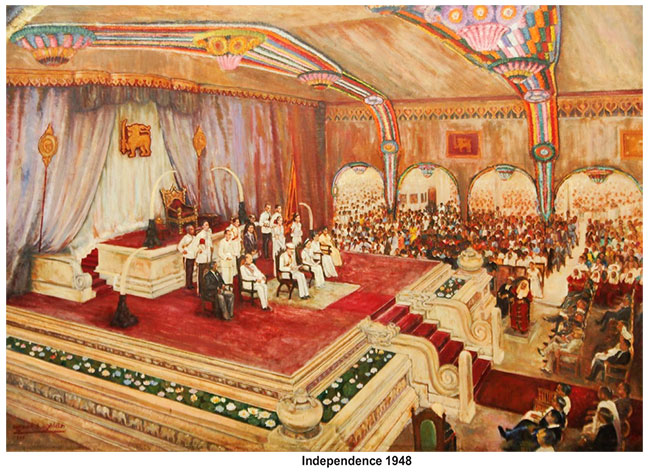

An untold history of Sri Lanka’s Independence

By Uditha Devapriya

In Sri Lank, as in every other colonial outpost, resistance to foreign domination predated Western intervention by well more than two centuries. Surviving numerous onslaughts of South Indian conquest, the Anuradhapura kingdom gave way to the Polonnaruwa kingdom in the 11th century AD. The latter’s demise 200 years later led to a shift from the country’s north to the north-west, and from there to the south-west. It was in the south-west that the Sinhalese first confronted European colonialism, a confrontation that pushed the Kotte and the Sitava kingdoms to the last bastion of Sinhalese rule, Kandy.

The shift to Kandy coincided with the commencement of Portuguese rule in the island. Both Portuguese and Dutch officials emphasised, and sharpened, the line between the Maritime Provinces and the kanda uda rata. The Sitavaka rulers, in particular Rajasinghe I, had fought both Portuguese suzerainty and Kotte domination. These encounters more or less breathed new life into the country’s long history of resistance to foreign rule.

The Kandyan kings inherited this legacy and imbibed this streak. But under them resistance to colonial subjugation acquired a new logic and a fresh vigour. That was to define the island’s struggle against imperialism for well more than three centuries.

Sri Lanka’s confrontations with European colonialism took place in the early part of what historians call the modern period. The social, political, and economic transformations inherent in this period had a considerable impact on the trajectory of European imperialism and anti-imperialism. For that reason, any examination of Sri Lanka’s fight against colonial rule and its eventual independence must evaluate a broad array of historical trends. While the island’s lunge into statehood in 1948 followed a long period of peasant, elite, and radical struggles against foreign domination, the analysis would be incomplete without reference to how European colonialism itself influenced the course of such struggles.

The period between the British annexation of the island and the declaration of independence (1815-1948) unfolded in four successive but interrelated stages. In the first stage between 1815 and 1848, British colonialism was compelled to reckon with the reality of an unending series of peasant uprisings, beginning in Uva-Wellassa in 1817 and culiminating in Matale three decades later. In keeping with similar insurrections in other colonial societies, these were essentially Janus-faced: on the one hand, they sought liberation for a repressed group, the Kandyan peasantry, while on the other they envisaged a return to a pre-colonial polity. Yet, whatever their motives, they wanted to free the country of foreign rule.

The British government realised too late, the folly of assuming that its political-military grip over the island would weaken, and prevail over, peasant resistance. Since the annexation of 1815, the colonial government had drawn and redrawn the country’s borders, breaking up the former Kandyan kingdom into Central and North-Western provinces and separating the Kandyan kingdom from its Sabaragamuwa and Wayamba peripheries. With these measures, officials hoped for the breakup of Kandyan unity. The aim of these processes, notes K. M. de Silva, was “to weaken the national feeling of the Kandyans”.

However, for obvious reasons, none of these reforms could quieten or dispel the spirit of resistance among the peasantry. The Kandyan peasantry never accepted the notion of Sri Lanka as a unitary and united administration overseen by the colonial government. Indeed, when the subject of constitutional reform came up in the 1920s, the Kandyan delegation demanded federal autonomy, predating Tamil nationalist claims for a separate homeland by three decades. This showed very clearly that the British policy of amalgamating the Kandyan provinces with the rest of the country had not really worked out.

To complicate matters further, while dealing with peasant rebellions colonial officials had to put up with the growth of an assertive, and often radical, middle-class. To give one example, the Matala Uprising was never limited to Matale and Kurunegala: it erupted in Colombo as well, where Sinhalese, Tamil, and Burgher middle-classes protested the government’s tax policies. K. M. de Silva observes that attempts by these middle-classes to influence Kandyan agitation “achieved little impact.” Yet that such an attempt was made at all showed that the colonial government had to reckon with two distinct dissenting groups.

The middle-classes may not have been revolutionaries, but as their interventions during the Matale Uprising showed, they could combine their dissatisfaction with the way things were with popular hatred of the government, to make their own demands. As a way of resolving this issue, between 1848 and 1870 – the second of the four periods pertinent to this essay – the colonial government began hiring and empowering a subservient elite, drawn from “the second echelon of the Kandyan nobility” as well as a low country bourgeoisie.

Newton Gunasinghe has noted the paradox underlying these reforms. While putting an end to the monopoly of the Kandyan aristocracy, the British government reactivated the very social relations that had undergirded traditional Kandyan society. By reviving rajakariya in modified form, feudal production relations in temple lands, and a network of gamsabhas, colonial authorities grafted archaic social customs and practices on what was, essentially, a capitalist mode of production. This had the effect of building up a class of subservient elites and reducing the revolutionary potential of the peasantry.

For a while, the strategy worked. However, while it kept the Kandyan peasantry in check and in control, it backfired when the same intermediate elite the government had employed to their ranks began demanding further reforms.

Here it’s important to clarify exactly what these elites wanted. In rebelling against the government, neither the newly co-opted aristocracy nor the middle-classes promoted the overthrow of the British government. They did not want a radical transformation of colonial society, largely because by then they had grown too dependent on that society to envisage, or desire, a Ceylon falling outside the British orbit. This is why, while clamouring for greater representation for themselves, they very carefully, and consistently, opposed the extension of the franchise. As Regi Siriwardena has noted, none of those celebrated as national heroes today – with the important exception of A. E. Goonesinha – wanted universal suffrage vis-à-vis the Donoughmore Commission. Such reforms had to be imposed on them.

Despite this, though, the British government’s policy of engaging with local elites worked fairly well. Colonial officials now had local emissaries through whom they could mediate potential peasant uprisings. Yet the policy necessitated the retention of archaic and quasi-feudal social relations, which in the long term stunted capitalist development. On the other hand, the new strategy paved the way for the revival of various art forms, most prominently the Dalada perahera. As scholars like Senake Bandaranayake have noted, the government defined the perimeters and the contours of cultural artefacts and objets d’art, ensuring that they were in line with the broader aim of legitimising colonial rule.

These reforms led, in the third period (1870-1915), to a Buddhist revival whose exponents alternated between championing opposing to and cooperation with colonial officials. These two lines were promoted, respectively, by the two Buddhist institutions of higher learning established in the late 19th century, Vidyalankara and Vidyodaya. While it’s rather difficult to draw a line between these two universities and their representatives, it is true, as H. L. Seneviratne suggests in The Work of Kings, that significant disagreements prevailed within the Buddhist clergy over the issue of British domination.

From their side, colonial authorities, especially governors like Henry Ward, William Gregory, and Arthur Gordon, sought closer cooperation with a conservative Buddhist bourgeoisie, legitimising British rule while implementing cultural and political reforms. Very often these reforms antagonised groups like Evangelical missionaries. Yet colonial officials ignored their concerns; endearing themselves to revivalists, orientalists, and moderate nationalist opinion to maintain the colonial administrative structure became the bigger priority.

The effect of these developments was to turn the Buddhist elite to the forefront of the reforms being supported by the British government. Towards the end of this period, the bourgeoisie, who were too entrenched economically in colonial rule to advocate radical change, yet too underrepresented politically to be content with the way things were, began to take the lead in these reforms through the Temperance Movement.

The Temperance Movement provided an impetus for a number of other organisations. K. M. de Silva has argued that none of them – not even the ambitious Ceylon National Association – fulfilled the aims for which they had been set up. Ranging from communal outfits like the Dutch Burgher Union to commercial groups like the Plumbago Merchants Union, these organisations, for the most, preferred gradual to radical change, dispensing with the sort of agitation politics that would come to define the Indian National Congress.

The Temperance Movement provided an impetus for a number of other organisations. K. M. de Silva has argued that none of them – not even the ambitious Ceylon National Association – fulfilled the aims for which they had been set up. Ranging from communal outfits like the Dutch Burgher Union to commercial groups like the Plumbago Merchants Union, these organisations, for the most, preferred gradual to radical change, dispensing with the sort of agitation politics that would come to define the Indian National Congress.

Moreover, Hector Abhayavardhana has noted that the bulk of the Sinhalese elite leadership consisted of “small men with narrow vision” who wanted to bring religion into politics. Any hopes for a multicultural alliance faded away with the establishment of Mahajana Sabhas, which campaigned for Buddhist candidates. However highly one may have thought of outfits like the Jaffna Youth Congress, the lack of enthusiasm for such alliances, among the colonial bourgeoisie, paved the way for their inevitable and tragic demise.

Meanwhile, the colonial bourgeoisie faced a more formidable foe, or competitor, in the form of nationalist firebrands like Anagarika Dharmapala. In a bid to blunt the fervour of such firebrands, who they viewed with much distaste, the Sinhalese bourgeoisie toed the Vidyodaya line, promoting change within the framework of a plantation economy while seeking more representation for themselves. This was necessitated by expedience: by the early 20th century a working class movement had begun to emerge in the country, as the Carters’ Strike of 1906 showed, and though it lacked proper leadership, it nevertheless concerned the bourgeoisie. Their rather ambivalent response to these developments had the unfortunate effect of stunting the rise of a mass struggle in the country.

The comprador bourgeoisie shot to fame, so to speak, with the 1915 riots. A point often forgotten in contemporary reconstructions of the riots is that none of the elites arrested by the British government posed a direct threat to colonial rule. As Kumari Jayawardena has pointed out, it was a case of official overreaction to the faintest threat of an anti-colonial uprising. Much like the J. R. Jayewardene government proscribing the Left after the 1983 riots, there was no link between the riots and the causes attributed to it, be it the supposed agitation of Buddhist elites or the politics of the Temperance Movement.

Kumari Jayawardena and K. M. de Silva point out that the period after the 1915 riots – the fourth period relevant to our discussion – witnessed the dulling down and fading away of the Buddhist revival. This is indeed what happened. In the person of Anagarika Dharmapala, the revival had brought together both reformist and radical streams. The Sinhalese elites, obviously cooperating with British authorities, marginalised him to the extent of excluding him from political activity. Yet Dharmapala’s departure from the island gave rise to newer parties and forms of struggle, many of them inspired by his vision. Among these, the most prominent was the Labour Party, founded in 1928 by A. E. Goonesinha.

Naturally enough, working class unrest dominated much of the post-1915 period, leading to the formation of a broad, radical Left. The newly formed Left identified the limitations of Goonesinha’s politics and sought to transcend them. To this end the establishment of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), in 1935, marked a pivotal turning point in the country’s lunge towards independent statehood. Envisioning a complete, radical transformation of society, its representatives and ideologues broke with the dominant political outfit of the day, the Ceylon National Congress, charting their own course.

The LSSP’s original objectives, as radical in their time as in ours, included the socialisation of the means of production, the attainment of complete independence, and the abolition of all forms of inequality, including caste. Given the state of the economy at the time – it was a plantation enclave heavily dependent on a few sectors – no other programme would have sufficed for an organisation calling for a mass struggle against colonial rule. It goes without saying that it was the stalwarts of the Marxist Left – specifically Philip Gunawardena – who first advocated complete independence for Ceylon.

In the meantime, the colonial bourgeoisie managed, rather dismally, to turn the Ceylon National Congress into a pale echo of what it had once aspired to. With the departure of Ponnambalam Arunachalam in 1921, there came an end to an era where, as K. M. de Silva and Hector Abhayavardhana have observed, Sinhala and Tamil communities constituted in unison the majority of the country. In the hands of a predominantly Sinhalese bourgeoisie the Congress became a little more than a communal organisation, a point reinforced by the decision of its leaders to disenfranchise estate Tamils. In this they were occupied more than anything else with the preservation of their economic interests.

All these developments led to a situation where the Left could claim, very validly, that the ruling elite had not won independence, but had secured it on a platter from Whitehall. The elite themselves were not unaware of the inadequacy of their campaign for freedom: when the masses reacted vociferously against the cosmetic reforms they had obtained from the British government, the Congress bourgeoisie quickly went back and pressed for what was being demanded. Yet tied to three agreements which made the defence, foreign policy, and civil service blanks of the government subservient to British interests, Ceylon could become free only through a radical transformation of its political structures.

In breaking off all remaining ties with the colonial government, the 1972 Constitution sought to give effect to such a transformation. By then even the Sinhalese bourgeoisie had come to realise the folly of maintaining the status quo and the inevitability of change: whereas John Kotelawala could support Ceylon remaining a Dominion, Dudley Senanayake could a decade later support the idea of it becoming a Republic within the Commonwealth.

I believe we need a new account of our country’s emergence as an independent state. The accounts we have at present, barring very few, glorify one set of leaders over all others, marginalising and excluding everyone else. Conventional narratives depict the colonial elite as national heroes. This was not always so, though important differences did exist within the bourgeoisie. What we have learnt about our own independence is hardly adequate to the task of helping us understand our past. We badly need a new history.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

SL urged to use GSP+ to the fullest to promote export development

Sri Lanka needs to take full stock of its current economic situation and use to the maximum the potential in its GSP+ facility for export sector growth. In the process, it should ensure that it cooperates fully with the European Union. The urgency of undertaking these responsibilities is underscored by the issues growing out of the recent US decision to sweepingly hike tariffs on its imports, though differentially.

Sri Lanka needs to take full stock of its current economic situation and use to the maximum the potential in its GSP+ facility for export sector growth. In the process, it should ensure that it cooperates fully with the European Union. The urgency of undertaking these responsibilities is underscored by the issues growing out of the recent US decision to sweepingly hike tariffs on its imports, though differentially.

These were principal ‘takes’ for participants in the Pathfinder Foundation’s Ambassadors’ Roundtable forum held on April 8th at the Colombo Club of the Taj Samudra. The main presenter at the event was Ms. Carmen Moreno Raymundo, Ambassador of the European Union to Sri Lanka and the Maldives. The forum was chaired by Ambassador Bernard Goonetilleke, Chairman, Pathfinder Foundation. The event brought together a cross-section of the local public, including the media.

Ms. Moreno drew attention to the fact Sri Lanka is at present severely under utilizing its GSP+ facility, which is the main means for Sri Lanka to enter the very vast EU market of 450 million people. In fact the EU has been Sri Lanka’s biggest trading partner. In 2023, for instance, total trade between the partners stood at Euros 3.84 billion. There is no greater market but the EU region for Sri Lanka.

‘However, only Sri Lanka’s apparel sector has seen considerable growth over the years. It is the only export sector in Sri Lanka which could be said to be fully developed. However, wider ranging export growth is possible provided Sri Lanka exploits to the fullest the opportunities presented by GSP+.’

Moreno added, among other things: ‘Sri Lanka is one among only eight countries that have been granted the EU’s GSP+ facility. The wide-ranging export possibilities opened by the facility are waiting to be utilized. In the process, the country needs to participate in world trade in a dynamic way. It cannot opt for a closed economy. As long as economic vibrancy remains unachieved, Sri Lanka cannot enter into world trading arrangements from a strong position. Among other things, Sri Lanka must access the tools that will enable it to spot and make full use of export opportunities.

‘Sri Lanka must facilitate the private sector in a major way and make it possible for foreign investors to enter the local economy with no hassle and compete for local business opportunities unfettered. At present, Lanka lacks the relevant legal framework to make all this happen satisfactorily.

‘Sri Lanka cannot opt for what could be seen as opaque arrangements with bilateral economic partners. Transparency must be made to prevail in its dealings with investors and other relevant quarters. It’s the public good that must be ensured. The EU would like to see the local economy further opening up for foreign investment.

‘However, it is important that Sri Lanka cooperates with the EU in the latter’s efforts to bring about beneficial outcomes for Sri Lankans. Cooperation could be ensured by Sri Lanka fully abiding by the EU conditions that are attendant on the granting of GSP+. There are, for example, a number of commitments and international conventions that Sri Lanka signed up to and had promised to implement on its receipt of GSP+ which have hitherto not been complied with. Some of these relate to human rights and labour regulations.

‘Successive governments have pledged to implement these conventions but thus far nothing has happened by way of compliance. GSP+ must be seen as an opportunity and not a threat and by complying with EU conditions the best fruits could be reaped from GSP+. It is relevant to remember that GSP+ was granted to Sri Lanka in 2005. It was suspended five years later and restored in 2017.

‘The importance of compliance with EU conditions is greatly enhanced at present in view of the fact that Sri Lanka is currently being monitored by the EU with regard to compliance ahead of extending GSP+ next year. A report on Sri Lanka is due next year wherein the country’s performance with regard to cooperating with the EU would be assessed. The continuation of the facility depends on the degree of cooperation.

‘A few statistics would bear out the importance of Sri Lanka’s partnership with the EU. For example, under the facility Sri Lanka benefits from duty free access in over 66% of EU tariff lines. The highest number of tourist arrivals in Sri Lanka in 2023 was from the EU’s 27 member states. Likewise, the EU’s 27 member states rank second in the origin of inflows of foreign exchange to Sri Lanka; with Italy, France and Germany figuring as the main countries of origin. Eighty five percent of Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU market benefits from GSP+. Thus, the stakes for the country are high.’

Meanwhile, President, In-house Counsel & Legal Advisor, The European Chamber of Commerce of Sri Lanka, John Wilson said: ‘GSP+ should be seen as not only an opportunity but also as a necessity by Sri Lanka in the current international economic climate. ‘Implementation of local laws is what is needed. Considering the pressures growing out of the US imposed new tariff regime, a good dialogue with the EU is needed.

‘Sri Lanka’s level of business readiness must be upped. Among the imperatives are: An electronic procurement process, Customs reforms, a ‘National Single Window’, stepped-up access to land by investors, for example, a clear policy framework on PPPs and reform of the work permits system.’

It ought to be plain to see from the foregoing that Sri Lanka cannot afford to lose the GSP+ facility if it is stepped-up economic growth that is aimed at. It would be in Sri Lanka’s best interests to remain linked with the EU, considering the aggravated material hardships that could come in the wake of the imposition of the US’ new tariff regime. Sri Lanka would need to remain in a dialogue process with the EU, voice its reservations on matters growing out of GSP+, if any, iron out differences and ensure that its national interest is secured.

Features

SENSITIVE AND PASSIONATE…

Chit-Chat

Chiara Tissera

Mrs. Queen of the World Sri Lanka 2024, Chiara Tissera, leaves for the finals, in the USA, next month

I had a very interesting chat with her and this is how it all went:

1. How would you describe yourself?

I am a sensitive and passionate individual who deeply cares about the things that matter most to me. I approach life with a heart full of enthusiasm and a desire to make meaningful connections.

2. If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be?

Actually, I wouldn’t change a thing about myself because the person I am today, both inside and out, is the result of everything I’ve experienced. Every part of me has shaped who I am, so I embrace both my strengths and imperfections as they make me uniquely me.

3. If you could change one thing about your family, what would it be?

If there’s one thing I could change about my family, it would be having my father back with us. Losing him six years ago left a void that can never be filled, but his memory continues to guide and inspire us every day.

4. School?

I went to St. Jude’s College, Kurana, and I’m really proud to say that the lessons I gained during my time there have shaped who I am today. My school and teachers instilled in me values of hard work, perseverance and the importance of community, and I carry those lessons with me every day. I was a senior prefect and was selected the Deputy Head Prefect of our college during my tenure.

5. Happiest moment?

The happiest moment of my life so far has been winning the Mrs. Sri Lanka 2024 for Queen of the World. It was a dream come true and a truly unforgettable experience, one that fills me with pride and gratitude every time I reflect on it.

6. What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Happiness is a deeply personal and multifaceted feeling that often comes from a sense of contentment, fulfillment and well-being. For me, perfect happiness is in moments of joy, peace and accomplishments … and also being surrounded by my loved ones.

7. Are you religious?

Yes, I’m a very religious person. And I’m a firm believer in God. My faith guides me through life, providing strength, dedication and a sense of peace in every situation. I live by the quote, ‘Do your best, and God will do the rest.’

8. Are you superstitious?

I’m not superstitious. I believe in making my own decisions and relying on logic and faith rather than following superstitions.

9. Your ideal guy?

My ideal guy is my husband. He is compassionate, understanding and is always there to support me, no matter what. He’s my rock and my best friend – truly everything I could ever want in a partner.

10. Which living person do you most admire?

The living person I admire the most is definitely my mummy. Her strength, love and unwavering support has shaped me into who I am today. She is my role model and she inspires me every day with her wisdom and kindness.

11. Your most treasured possession?

My most treasured possession is my family. They are the heart of my life, providing me with love, support and strength. Their presence is my greatest blessing.

12. If you were marooned on a desert island, who would you like as your companion?

I would like to have my spouse as my companion. Together, we could make the best of the situation, supporting each other, sharing moments of laughter and finding creative ways to survive and thrive.

13. Your most embarrassing moment?

There’s quite a few, for sure, but nothing is really coming to mind right now.

14. Done anything daring?

Yes, stepping out of my comfort zone and taking part in a pageant. I had no experience and was nervous about putting myself out there, but I decided to challenge myself and go for it. It pushed me to grow in so many ways—learning to embrace confidence, handle pressure, and appreciate my own uniqueness. The experience not only boosted my self-esteem but also taught me the value of taking risks and embracing new opportunities, even when they feel intimidating.”

15. Your ideal vacation?

It would be to Paris. The city has such a magical vibe and, of course, exploring the magical Eiffel Tower is in my bucket list. Especially the city being a mix of history culture and modern life in a way that feels timeless, I find it to be the ideal vacation spot for me.

16. What kind of music are you into?

I love romantic songs. I’m drawn to its emotional depth and the way they express love, longing a connection. Whether it’s a slow ballad, a classic love song or a more modern romantic tune these songs speak to my heart.

17. Favourite radio station?

I don’t have a specific radio station that I like, but I tend to enjoy a variety of stations, depending on my mood. Sometimes I’ll tune into one for a mix of popular hits, other times I might go for something more relaxing, or a station with a certain vibe. So I just like to keep it flexible and switch it up.

18. Favourite TV station?

I hardly find the time to sit down and watch TV. But, whenever I do find a little spare time, I tend to do some spontaneous binge – watching, catching whatever interesting show is on at that moment.

19 What would you like to be born as in your next life?

Mmmm, I’ve actually not thought about it, but I’d love to be born as someone who gets to explore the world freely – perhaps a bird soaring across continents.

20. Any major plans for the future?

Let’s say preparing and participating in the international pageant happening in the USA this May. It’s an exciting opportunity to represent myself and my country on a global stage. Alongside this, I am dedicated to continuing my social service work as a title holder, striving to make a meaningful difference in the lives of others through my platform.

Features

Fresher looking skin …

The formation of wrinkles and fine lines is part of our ageing process. However, if these wrinkles negatively impact appearance, making one look older than they actually are, then trying out some homemade remedies, I’ve listed for you, this week, may help in giving your skin a fresher look.

The formation of wrinkles and fine lines is part of our ageing process. However, if these wrinkles negatively impact appearance, making one look older than they actually are, then trying out some homemade remedies, I’ve listed for you, this week, may help in giving your skin a fresher look.

* Banana:

Bananas are considered to be our skin’s best friend. They contain natural oils and vitamins that work very perfectly to boost our skin health. Skincare experts recommend applying the banana paste to the skin.

Take a ripe banana and mash a quarter of it until it becomes a smooth paste. Apply a thin layer of the banana paste on your skin and allow it to sit for 15 to 20 minutes before washing it off with warm water.

* Olive Oil:

Olive oil works as a great skin protector and many types of research suggest that even consuming olive oil may protect the skin from developing more wrinkles. Olive oil contains compounds that can increase the skin’s collagen levels. Yes, olive oil can be used as a dressing on your salads, or other food, if you want to consume it, otherwise, you can apply a thin layer of olive oil on your face, neck and hands and let it stay overnight.

* Ginger:

Ginger serves to be a brilliant anti-wrinkle remedy because of the high content of antioxidants in it. Ginger helps in breaking down elastin, which is one of the main reasons for wrinkles. You can have ginger tea or grate ginger and have it with honey, on a regular basis.

* Aloe Vera:

The malic acid present in Aloe Vera helps in improving your skin’s elasticity, which helps in reducing your wrinkles. Apply the gel once you extract it from the plant, and leave it on for 15-20 minutes. You can wash it off with warm water.

* Lemons:

Lemons contain citric acid, which is a strong exfoliant that can help you get rid of your dead skin cells and wrinkles. Also, as an astringent and a cleansing agent, it helps to fade your wrinkles and fine lines. You can gently rub a lemon slice in your wrinkled skin and leave it on for 10-15 minutes. Rinse afterwards and repeat this process two to three times a day.

* Coconut Oil:

Coconut oil contains essential fatty acid that moisturises the skin and helps to retain its elasticity. You can directly apply the coconut oil, and leave it overnight, after gently massaging it, for the best results.

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoColombo Coffee wins coveted management awards

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDaraz Sri Lanka ushers in the New Year with 4.4 Avurudu Wasi Pro Max – Sri Lanka’s biggest online Avurudu sale

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoStarlink in the Global South

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoStrengthening SDG integration into provincial planning and development process

-

Business6 days ago

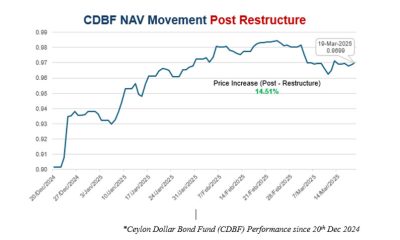

Business6 days agoNew SL Sovereign Bonds win foreign investor confidence

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoSri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part III

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoModi’s Sri Lanka Sojourn

-

Midweek Review2 days ago

Midweek Review2 days agoInequality is killing the Middle Class