Features

Educational reforms Sri Lanka demands today for a brighter tomorrow

The 32nd Dr. C. W. W. Kannangara Memorial Lecture titled ‘For a country with a future’: Educational reforms Sri Lanka demands today’ delivered by Prof. Athula Sumathipala, Director, Institute for Research and Development, Sri Lanka and Chairman, National Institute of Fundemental Studies, Hanthana on Oct 13 at the National Institute of Education, Maharagama

Continued From Friday (21)

We believe the child who is ready to face the challenges of the 21st century is a child who meets all these requirements.”

They have identified six aims of general education as shown below. National aims of general education

1. An active contributor to national development

2. An effective and efficient employee or smart self-employee

3. An entrepreneur or person with an entrepreneurial mindset

4. A patriotic citizen

5. A good human

6. A member of a happy family

These six aims are divided into nine parts as follows.

1. Positive

2. Practical

3. Proactive

4. Pragmatic

5. Patriotic

6. Passionate

7. Peace loving

8. Preserving

9. Problem solver

The new educational reforms have identified the skills necessary to the child of the 21st century, as follows.

The twelve 21st century skills

Learning skills

1. Critical thinking and problem solving

2. Creativity

3. Collaborations and teamwork

4. Communication knowledge

Literacy skills

5. Information literacy

6. Media literacy

7. Technology literacy

Life skills

8. Flexibility

9. Leadership

10. Initiative

11. Productivity

12. Social skills

We then discuss social skills under six different criteria.

1. Understanding oneself

2. Managing oneself

3. Understanding others

4. Building and managing positive relationships with others

5. Relationship with the environment

6. Responsible decision making

Main domains of national reforms:

It is evident that these reforms have been proposed after in-depth analysis and that they are conceptually excellent plans. They are also well in line with the vision of Dr. Kannangara. The challenge, however, is how to effect these reforms in this country, given the social, economic and political challenges we are facing.

On the one hand, it is becoming impossible to hold school on all five days due to the fuel crisis. On the other hand, the question is how technical difficulties and shortcomings of on-line teaching can impact these reforms. Furthermore, it is very likely that these reforms will be viewed within a political framework by both union leaders and student unions.

The level of understanding of the key stakeholders of these reforms when they are being introduced will obviously be at different levels. Communicating these reforms to the different stakeholders at a level that they can clearly understand it will be a significant challenge. There appears to be a significant shortfall in employing social and electronic media, as well as influencers, to effectively communicate about these reforms, and we have a social responsibility to warn about this shortfall.

It is human nature to resist change. It is critically important to clearly communicate to the public, why the current education system needs to change, how it should change, how the direction of change and its final objectives are decided, in such a way that it addresses their fears and concerns. No one should be offended if I remind you that failure to carry out effective communication could lead to the same end as that of the proposal to shift to organic fertilisers.

Furthermore, however great the reforms are, it is necessary to remember that opposition against highly sensitive matters such as the Grade 5 scholarship examination, may come from those whose livelihood depends on tuition classes. It is also necessary to keep in mind that even the elements of society who are demanding a ‘system change’ may well behave in a different way when it is something that will affect them personally. As psychology tells us, this is because that the way we think when it is our personal problem is different to how we think when it is someone else’s problem. Another important challenge is how teachers’ mentalities can be aligned with these reforms. This does not mean that we assume opposition from the majority of teachers. However, it is doubtful if we have sufficient research data to determine the reality of this issue.

I would like to reiterate that the authorities, intellectuals and politicians already possess the mechanisms and strategies to win this massive challenge of effectively communicating these changes to all relevant layers of society and to convert them to honoured stakeholders of this change. Such strategic communication needs to be positioned as one of the most important aspects of the implementation of these reforms.

Other segments within the big picture that merit attention apart from the reforms within the school system in years 1-13

i. Early childhood development and the first 1,000 days

ii. The role of pre-schools as part of the education system

iii. Inclusive education and children with special needs

iv. Contribution of distance learning to educational reforms and challenges

v. Relationship between education and health

vi. Private universities and educational institutions

vii. Students at universities abroad

viii. Life-long education, adult education, continuous education for education professionals

ix. Integrating research within the overall scheme of education

Since there isn’t sufficient time to discuss all these sections fully, I will discuss some of the sections I believe are the most important.

(i) Early childhood development and the first 1,000 days

The greatest importance and greatest weight when investing in a child should be attached to the first 1,000 days. This is because 80% of a child’s brain development is completed within the first three years. Therefore, significant investment in educational reforms should be allocated to early childhood development, i.e., the Golden 1,000 days. A strong foundation laid at this stage will help the child successfully complete his / her education. From a health perspective, the Health Department, particularly the Family Health Bureau, makes a meaningful contribution towards this objective, however, there is a lack of an active mechanism to enrol parents as honoured stakeholders within this process. This is important because responsive care giving, i.e., observing a child’s signals in a timely and accurate manner, understanding such signals and responding to them, is an important part of childhood development.

Early childhood protection cannot be achieved through pre-established rules and guidance. Parents need to understand the related scientific concepts and should incorporate these concepts into their day-to-day life. The relationship with children varies according to the parents, therefore parents need to analyse the existing interactions with their children and secondly, adapt these measures and develop them to suit their needs. However, there is no structured mechanism for parents to develop this skill set within the education system, nor within the health system.

I do no intend to discuss this in detail, but wish to point out the critical importance of this concept; to reiterate that the greatest investment is necessary in the first 1,000 days, far more than in the Grade 5 scholarship exam, the Ordinary Level or Advanced Level examinations. Stimulating brain development is an investment with high returns; the best investment for the Sri Lankan nation. Research data indicates that for every Rs.200 invested on brain development, the return can be valued at Rs.1 800

(ii) The role of pre-schools as part of the education system

I shall quote from the article Mala. N. De Silva, retired Deputy Head, National Education Faculty, published in the 39th edition of Gaveshana, that explained our stance on the role of pre-schools in educational reforms. A pre-school has been recognised as the ‘Golden door that gives a person access to society’. De Silva writes quoting Koswatte Ariyawimala Thero that “The role of a preschool is not to give a child a large number of modern toys. Neither is it to teach a child to recite a poem in English. Those are secondary. A pre-school is not a tutory. It is the place where small children play; where they form social relations. That is what human education is.”

Furthermore, the UNESCO report on ‘Education for Life’ states that pre-school education is a prior necessity for any educational or cultural system, indicating the importance of pre-schools. At the World Children’s Summit in 1990 in New York, the world’s leaders signed the ‘World Declaration on the Survival, Protection and Development of Children’, which had as its primary claim that early childhood should be a time of ‘joy and peace, of playing, learning and growing’.

The educational reforms of 1997 too had significant focus on early childhood education: it recommends increasing the number of pre-schools so that 3–5-year-olds can receive a better education. The National Census on early childhood education centres estimated that there are 19,668 pre-schools in Sri Lanka. The majority of these are, however, privately owned, and many parents cannot bear the cost of these schools. These pre-schools are frequently un-monitored and not standardised.

Under these conditions, I would like to reiterate that these pre-schools should be monitored and that the process of providing resource persons at these schools an adequate training needs to be expanded significantly.

(iii) Inclusive education and children with special needs

I would like to present a few points here based on the article written by Binoli Herath of the Institute for Research and Development on this topic.

‘All children have an equal right to education; however, it is not a secret that children with special needs face multiple challenges in accessing and receiving education’.

‘These children often are disregarded in society due to disabilities, poverty and the extreme nature of their problems. Most of them are unaware of the opportunities available to them. Similarly, most people are unaware of the abilities such children can possess’.

The Ayati Centre affiliated with the Kelaniya University provides health and education services for children with special needs with the mission to help such children reach their maximum potential through the use of modern scientific interventions and expertise. It also serves as a training centre for resource persons and as a research centre. There is great need to expand such services throughout the country.

I believe it is important to discuss alternative education for children with special needs.

1. Specialised schools: these are pre-schools, primary, junior secondary and senior secondary schools for children with relatively severe disabilities. Children with severe visual, auditory, physical or cognitive disabilities receive education in such specialised schools using specifically adapted curricula.

2. Special education units within mainstream schools: children with special needs can be educated in units specifically established for them.

3. Special resource centres attached to mainstream schools: children with special needs enter regular classes and work within them for the majority of the time whilst seeking special services necessary from the resource centres a few times a week. Such schemes provide necessary support to children with speech difficulties, autism, emotional disorders, auditory or visual difficulties, learning difficulties, attention disorders and ADHD, for example.

4. Inclusive mainstream schools: provide education to children with special needs in the mainstream schools. This is feasible for children with mild disorders who can enter mainstream schools.

These facilities are available to some level within the education system; however, educational reforms should include mechanisms to elevate the entire society to one that acts positively towards children with special needs and does not discriminate against them. Education systems for children with special needs usually follow the curricula in the mainstream schools, however, these systems need to be modernised, along with making modern equipment and trained teachers available.

(iv) Distance learning as a tool for educational reforms and challenges faced

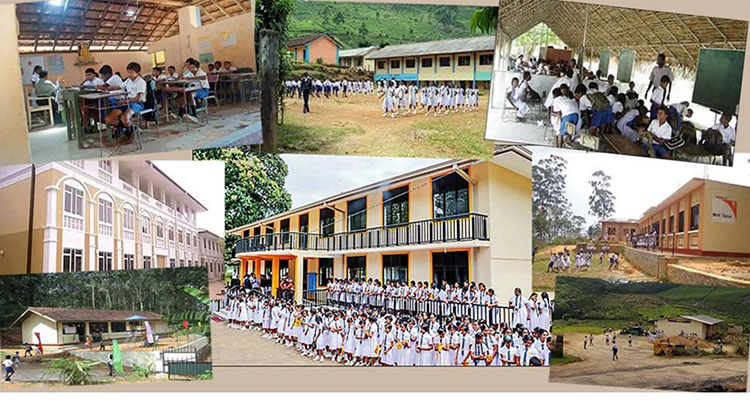

We discussed this issue with Neil Gunadasa, Additional Secretary, State Ministry for Educational Reforms, Open Universities and Development of Distance Education. He explained that certain sections of distance education functioned to a limited extent within the general education system. Recently, a separate Distance Education Unit was established to make distance education an integral part of general education.

“With the increased use of modern technology such as computers, tablets, internet and smart phones, the stage had already been set for the expansion of distance learning. The advent of Covid 19 and the resultant issues helped further popularise distance learning.

The Information Technology Division of the Ministry of Education initiated e-Thaksalawa, a structured distance learning system which contained a limited amount of learning media for children. They have developed it further now so that it can be used for educational reforms. This system is similar to a virtual classroom, carrying out the process that usually happens in a classroom on a virtual basis, using technologies such as Microsoft Teams and Zoom.

All 10,165 schools in Sri Lanka have been added to the system and it is expected to facilitate any student pre-booking and accessing the lectures of any teacher. The e-Thaksalawa content is prepared to match the new educational reforms which offer lessons in a module system. For example, a student completing a ten-hour module receives one credit. Learning the module content may well be done at school, but e-Thaksalawa offers the student the possibility of expanding his knowledge of the subject matter further using extension material.

Content creation has been done in all three languages, using both teachers and external subject matter experts. For example, for a topic such as agriculture, experts on agriculture are invited to contribute to content creation. Steps are being taken to provide students knowledge of more subject-related matter using the internet and distance learning methods. The 107 computer centres covering every educational division in the country are to be developed further to use as local resource centres for the new reforms.

Features

Ramadan 2026: Fasting hours around the world

The Muslim holy month of Ramadan is set to begin on February 18 or 19, depending on the sighting of the crescent moon.

During the month, which lasts 29 or 30 days, Muslims observing the fast will refrain from eating and drinking from dawn to dusk, typically for a period of 12 to 15 hours, depending on their location.

Muslims believe Ramadan is the month when the first verses of the Quran were revealed to the Prophet Muhammad more than 1,400 years ago.

The fast entails abstinence from eating, drinking, smoking and sexual relations during daylight hours to achieve greater “taqwa”, or consciousness of God.

Why does Ramadan start on different dates every year?

Ramadan begins 10 to 12 days earlier each year. This is because the Islamic calendar is based on the lunar Hijri calendar, with months that are 29 or 30 days long.

For nearly 90 percent of the world’s population living in the Northern Hemisphere, the number of fasting hours will be a bit shorter this year and will continue to decrease until 2031, when Ramadan will encompass the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year.

For fasting Muslims living south of the equator, the number of fasting hours will be longer than last year.

Because the lunar year is shorter than the solar year by 11 days, Ramadan will be observed twice in the year 2030 – first beginning on January 5 and then starting on December 26.

Fasting hours around the world

The number of daylight hours varies across the world.

Since it is winter in the Northern Hemisphere, this Ramadan, people living there will have the shortest fasts, lasting about 12 to 13 hours on the first day, with the duration increasing throughout the month.

People in southern countries like Chile, New Zealand, and South Africa will have the longest fasts, lasting about 14 to 15 hours on the first day. However, the number of fasting hours will decrease throughout the month.

[Aljazeera]

Features

The education crossroads:Liberating Sri Lankan classroom and moving ahead

Education reforms have triggered a national debate, and it is time to shift our focus from the mantra of memorising facts to mastering the art of thinking as an educational tool for the children of our land: the glorious future of Sri Lanka.

The 2026 National Education Reform Agenda is an ambitious attempt to transform a century-old colonial relic of rote-learning into a modern, competency-based system. Yet for all that, as the headlines oscillate between the “smooth rollout” of Grade 01 reforms and the “suspension of Grade 06 modules,” due to various mishaps, a deeper question remains: Do we truly and clearly understand how a human being learns?

Education is ever so often mistaken for the volume of facts a student can carry in his or her head until the day of an examination. In Sri Lanka the “Scholarship Exam” (Grade 05) and the O-Level/A-Level hurdles have created a culture where the brain is treated as a computer hard drive that stores data, rather than a superbly competent processor of information.

However, neuroscience and global success stories clearly project a different perspective. To reform our schools, we must first understand the journey of the human mind, from the first breath of infancy to the complex thresholds of adulthood.

The Architecture of the Early Mind: Infancy to Age 05

The journey begins not with a textbook, but with, in tennis jargon, a “serve and return” interaction. When a little infant babbles, and a parent responds with a smile or a word or a sentence, neural connections are forged at a rate of over one million per second. This is the foundation of cognitive architecture, the basis of learning. The baby learns that the parent is responsive to his or her antics and it is stored in his or her brain.

In Scandinavian countries like Finland and Norway, globally recognised and appreciated for their fantastic educational facilities, formal schooling does not even begin until age seven. Instead, the early years are dedicated to play-based learning. One might ask why? It is because neuroscience has clearly shown that play is the “work” of the child. Through play, children develop executive functions, responsiveness, impulse control, working memory, and mental flexibility.

In Sri Lanka, we often rush like the blazes on earth to put a pencil in the hand of a three-year-old, and then firmly demanding the child writes the alphabet. Contrast this with the United Kingdom’s “Birth to 5 Matters” framework. That initiative prioritises “self-regulation”, the ability to manage emotions and focus. A child who can regulate their emotions is a child who can eventually solve a quadratic equation. However, a child who is forced to memorise before they can play, often develops “school burnout” even before they hit puberty.

The Primary Years: Discovery vs. Dictation

As children move into the primary years (ages 06 to 12), the brain’s “neuroplasticity” is at its peak. Neuroplasticity refers to the malleability of the human brain. It is the brain’s ability to physically rewire its neural pathways in response to new information or the environment. This is the window where the “how” of learning becomes a lot more important than the “what” that the child should learn.

Singapore is often ranked number one in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores. It is a worldwide study conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that measures the scholastic performance of 15-year-old students in mathematics, science, and reading. It is considered to be the gold standard for measuring “education” because it does not test whether students can remember facts. Instead, it tests whether they can apply what they have learned to solve real-world problems; a truism that perfectly aligns with the argument that memorisation is not true or even valuable education. Singapore has moved away from its old reputation for “pressure-cooker” education. Their current mantra is “Teach Less, Learn More.” They have reduced the syllabus to give teachers room to facilitate inquiry. They use the “Concrete-Pictorial-Abstract” approach to mathematics, ensuring children understand the logic of numbers before they are asked to memorise formulae.

In Japan, the primary curriculum emphasises Moral Education (dotoku) and Special Activities (tokkatsu). Children learn to clean their own classrooms and serve lunch. This is not just about performing routine chores; it really is as far as you can get away from it. It is about learning collaboration and social responsibility. The Japanese are wise enough to understand that even an absolutely brilliant scientist who cannot work in a team is a liability to society.

In Sri Lanka, the current debate over the 2026 reforms centres on the “ABCDE” framework: Attendance, Belongingness, Cleanliness, Discipline, and English. While these are noble goals, we must be careful not to turn “Belongingness” into just another checkbox. True learning in the primary years happens when a child feels safe enough to ask “Why?” without the fear of being told “Because it is in the syllabus” or, in extreme cases, “It is not your job to question it.” Those who perpetrate such remarks need to have their heads examined, because in the developed world, the word “Why” is considered to be a very powerful expression, as it demands answers that involve human reasoning.

The Adolescent Brain: The Search for Meaning

Between ages 12 and 18, the brain undergoes a massive refashioning or “pruning” process. The prefrontal cortex of the human brain, the seat of reasoning, is still under construction. This is why teenagers are often impulsive but also capable of profound idealism. However, with prudent and gentle guiding, the very same prefrontal cortex can be stimulated to reach much higher levels of reasoning.

The USA and UK models, despite their flaws, have pioneered “Project-Based Learning” (PBL). Instead of sitting for a history lecture, students might be tasked with creating a documentary or debating a mock trial. This forces them to use 21st-century skills, like critical thinking, communication, and digital literacy. For example, memorising the date of the Battle of Danture is a low-level cognitive task. Google can do it in 0.02 seconds or less. However, analysing why the battle was fought, and its impact on modern Sri Lankan identity, is a high-level cognitive task. The Battle of Danture in 1594 is one of the most significant military victories in Sri Lankan history. It was a decisive clash between the forces of the Kingdom of Kandy, led by King Vimaladharmasuriya 1, and the Portuguese Empire, led by Captain-General Pedro Lopes de Sousa. It proved that a smaller but highly motivated force with a deep understanding of its environment could defeat a globally dominant superpower. It ensured that the Kingdom of Kandy remained independent for another 221 years, until 1815. Without this victory, Sri Lanka might have become a full Portuguese colony much earlier. Children who are guided to appreciate the underlying reasons for the victory will remember it and appreciate it forever. Education must move from the “What” to the “So What about it?“

The Great Fallacy: Why Memorisation is Not Education

The most dangerous myth in Sri Lankan education is that a “good memory” equals a “good education.” A good memory that remembers information is a good thing. However, it is vital to come to terms with the concept that understanding allows children to link concepts, reason, and solve problems. Memorisation alone just results in superficial learning that does not last.

Neuroscience shows that when we learn through rote recall, the information is stored in “silos.” It stays put in a store but cannot be applied to new contexts. However, when we learn through understanding, we build a web of associations, an omnipotent ability to apply it to many a variegated circumstance.

Interestingly, a hybrid approach exists in some countries. In East Asian systems, as found in South Korea and China, “repetitive practice” is often used, not for mindless rote, but to achieve “fluency.” Just as a pianist practices scales to eventually play a concerto with soul sounds incorporated into it, a student might practice basic arithmetic to free up “working memory” for complex physics. The key is that the repetition must lead to a “deep” approach, not a superficial or “surface” one.

Some Suggestions for Sri Lanka’s Reform Initiatives

The “hullabaloo” in Sri Lanka regarding the 2026 reforms is, in many ways, a healthy sign. It shows that the country cares. That is a very good thing. However, the critics have valid points.

* The Digital Divide: Moving towards “digital integration” is progressive, but if the burden of buying digital tablets and computers falls on parents in rural villages, we are only deepening the inequality and iniquity gap. It is our responsibility to ensure that no child is left behind, especially because of poverty. Who knows? That child might turn out to be the greatest scientist of all time.

* Teacher Empowerment: You cannot have “learner-centred education” without “independent-thinking teachers.” If our teachers are treated as “cogs in a machine” following rigid manuals from the National Institute of Education (NIE), the students will never learn to think for themselves. We need to train teachers to be the stars of guidance. Mistakes do not require punishments; they simply require gentle corrections.

* Breadth vs. Depth: The current reform’s tendency to increase the number of “essential subjects”, even up to 15 in some modules, ever so clearly risks overwhelming the cognitive and neural capacities of students. The result would be an “academic burnout.” We should follow the Scandinavian model of depth over breadth: mastering a few things deeply is much better than skimming the surface of many.

The Road to Adulthood

By the time a young adult reaches 21, his or her brain is almost fully formed. The goal of the previous 20 years should not have been to fill a “vessel” with facts, but to “kindle a fire” of curiosity.

The most successful adults in the 2026 global economy or science are not those who can recite the periodic table from memory. They are those who possess grit, persistence, adaptability, reasoning, and empathy. These are “soft skills” that are actually the hardest to teach. More importantly, they are the ones that cannot be tested in a three-hour hall examination with a pen and paper.

A personal addendum

As a Consultant Paediatrician with over half a century of experience treating children, including kids struggling with physical ailments as well as those enduring mental health crises in many areas of our Motherland, I have seen the invisible scars of our education system. My work has often been the unintended ‘landing pad’ for students broken by the relentless stresses of rote-heavy curricula and the rigid, unforgiving and even violently exhibited expectations of teachers. We are currently operating a system that prioritises the ‘average’ while failing the individual. This is a catastrophe that needs to be addressed.

In addition, and most critically, we lack a formal mechanism to identify and nurture our “intellectually gifted” children. Unlike Singapore’s dedicated Gifted Education Programme (GEP), which identifies and provides specialised care for high-potential learners from a very young age, our system leaves these bright minds to wither in the boredom of standard classrooms or, worse, treats their brilliance as a behavioural problem to be suppressed. Please believe me, we do have equivalent numbers of gifted child intellectuals as any other nation on Mother Earth. They need to be found and carefully nurtured, even with kid gloves at times.

All these concerns really break my heart as I am a humble product of a fantastic free education system that nurtured me all those years ago. This Motherland of mine gave me everything that I have today, and I have never forgotten that. It is the main reason why I have elected to remain and work in this country, despite many opportunities offered to me from many other realms. I decided to write this piece in a supposedly valiant effort to anticipate that saner counsel would prevail finally, and all the children of tomorrow will be provided with the very same facilities that were afforded to me, right throughout my career. Ever so sadly, the current system falls ever so far from it.

Conclusion: A Fervent Call to Action

If we want Sri Lanka to thrive, we must stop asking our children, “What did you learn today?” and start asking, “What did you learn to question today?“

Education reform is not just about changing textbooks or introducing modules. It is, very definitely, about changing our national mindset. We must learn to equally value the artist as much as the doctor, and the critical thinker as much as the top scorer in exams. Let us look to the world, to the play of the Finns, the discipline of the Japanese, and the inquiry of the British, and learn from them. But, and this is a BIG BUT…, let us build a system that is uniquely Sri Lankan. We need a system that makes absolutely sure that our children enjoy learning. We must ensure that it is one where every child, without leaving even one of them behind, from the cradle to the graduation cap, is seen not as a memory bank, but as a mind waiting to be set free.

by Dr B. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paed), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka

Journal of Child Health]

Section Editor, Ceylon Medical Journal

Features

Giants in our backyard: Why Sri Lanka’s Blue Whales matter to the world

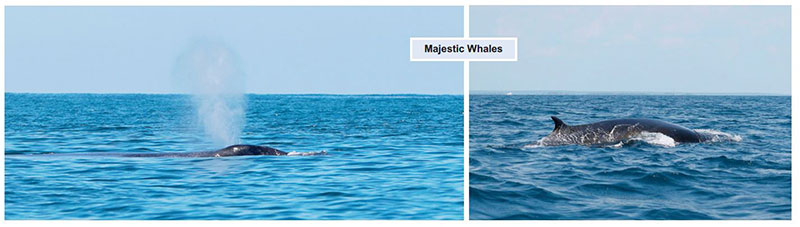

Standing on the southern tip of the island at Dondra Head, where the Indian Ocean stretches endlessly in every direction, it is difficult to imagine that beneath those restless blue waves lies one of the greatest wildlife spectacles on Earth.

Yet, according to Dr. Ranil Nanayakkara, Sri Lanka today is not just another tropical island with pretty beaches – it is one of the best places in the world to see blue whales, the largest animals ever to have lived on this planet.

“The waters around Sri Lanka are particularly good for blue whales due to a unique combination of geography and oceanographic conditions,” Dr. Nanayakkara told The Island. “We have a reliable and rich food source, and most importantly, a unique, year-round resident population.”

In a world where blue whales usually migrate thousands of kilometres between polar feeding grounds and tropical breeding areas, Sri Lanka offers something extraordinary – a non-migratory population of pygmy blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus indica) that stay around the island throughout the year. Instead of travelling to Antarctica, these giants simply shift their feeding grounds around the island, moving between the south and east coasts with the monsoons.

The secret lies beneath the surface. Seasonal monsoonal currents trigger upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water, which fuels massive blooms of phytoplankton. This, in turn, supports dense swarms of Sergestidae shrimps – tiny creatures that form the primary diet of Sri Lanka’s blue whales.

- “Engineers of the ocean system”

“Blue whales require dense aggregations of these shrimps to meet their massive energy needs,” Dr. Nanayakkara explained. “And the waters around Dondra Head and Trincomalee provide exactly that.”

Adding to this natural advantage is Sri Lanka’s narrow continental shelf. The seabed drops sharply into deep oceanic canyons just a few kilometres from the shore. This allows whales to feed in deep waters while remaining close enough to land to be observed from places like Mirissa and Trincomalee – a rare phenomenon anywhere in the world.

Dr. Nanayakkara’s journey into marine research began not in a laboratory, but in front of a television screen. As a child, he was captivated by the documentary Whales Weep Not by James R. Donaldson III – the first visual documentation of sperm and blue whales in Sri Lankan waters.

“That documentary planted the seed,” he recalled. “But what truly set my path was my first encounter with a sperm whale off Trincomalee. Seeing that animal surface just metres away was humbling. It made me realise that despite decades of conflict on land, Sri Lanka harbours globally significant marine treasures.”

Since then, his work has focused on cetaceans – from blue whales and sperm whales to tropical killer whales and elusive beaked whales. What continues to inspire him is both the scientific mystery and the human connection.

“These blue whales do not follow typical migration patterns. Their life cycles, communication and adaptability are still not fully understood,” he said. “And at the same time, seeing the awe in people’s eyes during whale watching trips reminds me why this work matters.”

Whale watching has become one of Sri Lanka’s fastest-growing tourism industries. On the south coast alone, thousands of tourists head out to sea every year in search of a glimpse of the giants. But Dr. Nanayakkara warned that without strict regulation, this boom could become a curse.

“We already have good guidelines – vessels must stay at least 100 metres away and maintain slow speeds,” he noted. “The problem is enforcement.”

Speaking to The Island, he stressed that Sri Lanka stands at a critical crossroads. “We can either become a global model for responsible ocean stewardship, or we can allow short-term economic interests to erode one of the most extraordinary marine ecosystems on the planet. The choice we make today will determine whether these giants continue to swim in our waters tomorrow.”

Beyond tourism, a far more dangerous threat looms over Sri Lanka’s whales – commercial shipping traffic. The main east-west shipping lanes pass directly through key blue whale habitats off the southern coast.

“The science is very clear,” Dr. Nanayakkara told The Island. “If we move the shipping lanes just 15 nautical miles south, we can reduce the risk of collisions by up to 95 percent.”

Such a move, however, requires political will and international cooperation through bodies like the International Maritime Organization and the International Whaling Commission.

“Ships travelling faster than 14 knots are far more likely to cause fatal injuries,” he added. “Reducing speeds to 10 knots in high-risk areas can cut fatal strikes by up to 90 percent. This is not guesswork – it is solid science.”

To most people, whales are simply majestic animals. But in ecological terms, they are far more than that – they are engineers of the ocean system itself.

Through a process known as the “whale pump”, whales bring nutrients from deep waters to the surface through their faeces, fertilising phytoplankton. These microscopic plants absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide, making whales indirect allies in the fight against climate change.

“When whales die and sink, they take all that carbon with them to the deep sea,” Dr. Nanayakkara said. “They literally lock carbon away for centuries.”

Even in death, whales create life. “Whale falls” – carcasses on the ocean floor – support unique deep-sea communities for decades.

“Protecting whales is not just about saving a species,” he said. “It is about protecting the ocean’s ability to function as a life-support system for the planet.”

For Dr. Nanayakkara, whales are not abstract data points – they are individuals with personalities and histories.

One of his most memorable encounters was with a female sperm whale nicknamed “Jaw”, missing part of her lower jaw.

“She surfaced right beside our boat, her massive eye level with mine,” he recalled. “In that moment, the line between observer and observed blurred. It was a reminder that these are sentient beings, not just research subjects.”

Another was with a tropical killer whale matriarch called “Notch”, who surfaced with her calf after a hunt.

“It felt like she was showing her offspring to us,” he said softly. “There was pride in her movement. It was extraordinary.”

Looking ahead, Dr. Nanayakkara envisions Sri Lanka as a global leader in a sustainable blue economy – where conservation and development go hand in hand.

“The ultimate goal is shared stewardship,” he told The Island. “When fishermen see healthy reefs as future income, and tour operators see protected whales as their greatest asset, conservation becomes everyone’s business.”

In the end, Sri Lanka’s greatest natural inheritance may not be its forests or mountains, but the silent giants gliding through its surrounding seas.

“Our ocean health is our greatest asset,” Dr. Nanayakkara said in conclusion. “If we protect it wisely, these whales will not just survive – they will define Sri Lanka’s place in the world.”

By Ifham Nizam

-

Life style1 day ago

Life style1 day agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Midweek Review5 days ago

Midweek Review5 days agoA question of national pride

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

Midweek Review5 days ago

Midweek Review5 days agoTheatre and Anthropocentrism in the age of Climate Emergency