Features

Dissenting with the Minister of Shipping

(Continued from last week)

The Managing Director of the Commonwealth Banking Corporation hosted a lunch for us in their 32nd floor dining room with a spectacular view of Melbourne. Felix Dias Abeysinghe, the former Elections Commissioner, about whom I have already written, was our High Commissioner in Australia, and it was a delight to meet him in Canberra. Whilst we were in Melbourne, our hosts knowing the interest of some of us in Cricket took us to the Melbourne cricket grounds to see a couple of hours play in the Third Test match between Australia and England. You just cannot capture the atmosphere on the ground by watching T.V. On T.V., you just get the Cricket.

But on the ground. you are part of a large community enjoying interesting and varied reactions. It’s far greater fun than being in the relative silence of a home or a hotel room. We were also told that the pressure to become a member of the Melbourne Cricket club was so great that children were put on the waiting list at birth. It was not everyone who made it before death! During the visit, my wedding anniversary came up, and the rest of the delegation knowing about this, sent up a large bowl of flowers to my room with a card signed by all, wishing us. This was very kind of them. I telephoned my wife and told her.

As usual, there were many matters to be followed up after the visit. But the main thing was that we had assured ourselves of another reliable source of supply of wheat for the new mill. We reached a range of understandings including on possible emergency purchases if necessary. Discussions held both in the United States and Australia made us feel much more secure as to the regular availability of the commodity. Tapping Canada was not possible due to high freight costs.

Coastal Shipping

Sri Lanka did not have a coastal shipping service at this time. The Ceylon Shipping Corporation of which I was a Director was not geared to handle coastal shipping. Their mandate was carrying cargo into and out of Sri Lanka. Certain officials of the Ceylon Shipping Lines however, showed an interest in developing a coastal service. There was.a ship sailing on in experimental basis and bringing some cement from the Kankesanturai factory.

But an occasional cargo of cement was not sufficient to sustain a coastal service. Some of the officers from “Shipping Lines” came to see me on this. During the discussions, it became quite clear that a coastal shipping service could not be a success without the full backing of the Food Ministry, perhaps the largest mover of cargoes. I could see the importance of attempting to start such a service, and I therefore undertook to study the question.

When I did so, it became apparent that the freight costs were going to be more than the alternative costs of road and rail transport. Therefore, from the Food Ministry’s point of view, carriage of food cargo by ships could not be justified on economic grounds.

But I was convinced that developing a coastal shipping service was a strategic necessity. One had to think beyond the requirements of just one Ministry. I had already seen at close quarters, the type of disruption caused to road and rail transport during the time of the insurgency of 1971 and episodes of strike action and disruption thereafter. We had large store complexes at the main Ports and particularly in an emergency, the operation of coastal vessels would lead to a greater ease in logistics and for greater food security.

I therefore, discussed all aspects of the matter fully with the Minister. I told him that even at a greater cost to us we should support the building up of a viable coastal shipping fleet in the national interest; that as an island with good strategically placed harbours, it would be advantageous to us naturally in the longer run; that the time has come for us to think in terms of developing a strategic vision and that there would be tangible ancillary benefits in the form of producing a core of trained seamen, whilst at the same time expanding employment opportunities for young people.

The Minister fully supported me in this thinking. He said that he would discuss matters with the President and obtain his approval. This was done, leading to the beginning of a coastal service with full Food Ministry backing. In fact the service was formally inaugurated somewhere in early November 1980. This led to other developments in due course with the private sector showing an interest, and a private company with German collaboration and investment emerging and putting in ships.

This in turn led to further developments when some powerful Singapore interests tried to kill the local venture and take over the coastal service. The Singapore attempt was an aggressive one, and soon there were rumours floating around of various officials being bribed. But we in the Food Ministry stood firm. We held the view that coastal shipping should be conducted by nationals of Sri Lanka in a National Company or Companies.

Foreign investment was in order. But Sri Lankan nationals should control the venture. This did not find favour with some, who adduced the argument that we were standing in the way of an improved Singapore directed service. Our position was that we had no objection to Singapore investment, but not a Singapore company owning and running the service. Unfortunately, in the end I myself had to come to the conclusion that the rumours of bribery were not without foundation, for when some of the representatives of this company came to see me they hinted at gold and jewellery, and holidays for my wife and myself. I was polite and pretended to be dense.

Given their influence locally at that point of time, I had no desire whatsoever to antagonize them. I merely played for time. Eventually, their bid failed, and the local venture took root. The importance of this service was demonstrated to us much earlier than one could have imagined. When the ethnic situation deteriorated seriously in 1983, the availability of coastal vessels proved to be crucial in sending a large number of Tamil citizens to the North.

This helped to stabilize a dangerous situation. It was also possible to move food and other cargoes when the country was under curfew. Subsequent events have proved with even greater force the enormous value of a coastal shipping service in Sri Lankan hands.

Dissenting with the Minister of Shipping

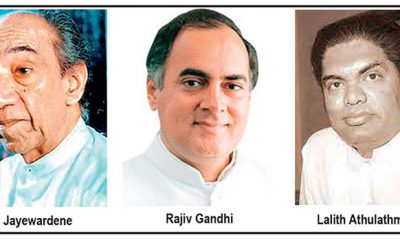

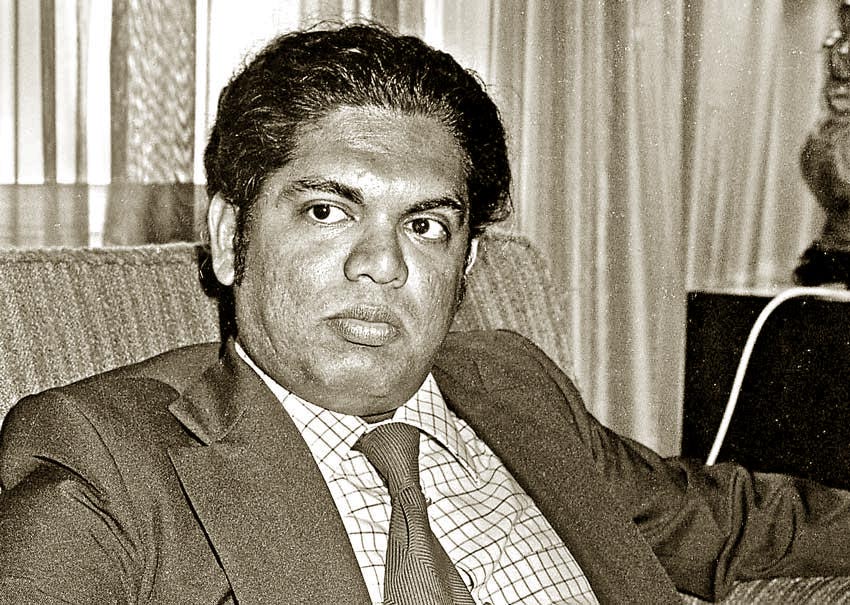

During the middle of 1980, I was summoned by Minister of Trade and Shipping Mr. Lalith Athulathmudali. The summons arose from something I had done as a Director of the Ceylon Shipping Corporation. The Board after careful consideration and after following due procedures had taken a decision on an important appointment to the Corporation. At the subsequent Board meeting Mr. M.L.D. Caspersz the Chairman, informed us that the Minister wanted someone else appointed. He mentioned his name. The Treasury representative Mr. Nalin Mendis, later to become Commissioner General of Inland Revenue, and I found it difficult to agree to this decision. Mr. Caspersz advised us in his fatherly manner that we should bow to the practical. This argument certainly had some merit. But both Nalin and I felt strongly enough to dissent.

To the considerable surprise of Mr. Caspersz both of us drafted separately to be included in the minutes, our inability to agree with the Minister’s order. In my draft, I added that I was not certain that the Minister was in full possession of the facts, and that I would like to be afforded an opportunity to personally explain matters to him, if he so desired. Hence the summons. When I appeared before him, with some trepidation, he had Secretary, Mr. Lakshman de Mel, and his two Additional Secretaries, Mr. Gaya Cumaranatunge and Mr. Harsha Wickremasinghe with him. “What is this all about?” inquired the Minister.

I explained. As I was speaking, the Minister was looking more and more surprised. “I didn’t know all this,” he said. “I thought not,” I replied. He immediately rescinded his order. He thanked me and said that his officers will bear witness that they could bring any disagreement to his attention and that they had the full freedom to do so. He said, he appreciated my stand. Then he asked his officials to remind him to talk to Mr. Caspersz, since he felt that he had not been given the full picture. Later in my career, I had the opportunity of serving as Mr. Athu lath mudal i’s Secretary in two different Ministries and I had no problem in telling him frankly, whatever needed to be said.

The Strike of 1980

In the midst of urgency and rapid change, where the government was making a major thrust towards policy changes and accelerated development came the general strike of July 1980. From the point of view of the strikers, the trade Unions that were in the forefront of the strike and the opposition politicians who encouraged and supported the strike, there were no doubt reasons. With the opening out of the economy and the restructuring of subsidies, the cost of living went up.

Prices rose to more realistic market levels. The agitation for wage increases reflected this situation. In addition to this, an authoritarian trend had manifested itself in government. Opposition Trade unions were strongly, sometimes harshly dealt with. Physical violence was unleashed on Trade Union demonstrators, some attackers wielding bicycle chains. It was in this overall context that the government reacted to an across the board wage demand. The result was a virtual general strike.

From the government’s point of view, the strike was a deliberate and planned act of sabotage by anti-government Trade Union elements, backed by opposition political parties, who sought to nullify the overwhelmingly popular mandate the government had received at the hustings. Therefore, their view was that unless the strike was ruthlessly crushed, it would open the door to interminable demands and wildcat strikes of a political nature intended to reduce government’s efficacy and thwart important policy changes and its programme of accelerated development. In other words, government was not prepared to view the strike as a last resort to redress genuine grievances.

They viewed it as a concerted attempt at political sabotage. Arising from this belief, action taken against those who struck work was harsh. After the expiry of an indicated deadline, those who did not return to work were all summarily dismissed from service. This was a shocking and unprecedented step which caused a great deal of disquiet in the public service as a whole. Government also decided to immediately fill the vacancies caused by these dismissals, so that very soon, Ministries and Departments were inundated with Government Members of Parliament, clamouring for the appointment of their favourites.

I personally felt that these were appallingly harsh decisions. Particularly, the decision to fill the vacancies meant that there was no hope of any of the striking officers coming back. Even if it was government policy to inflict stern punishment, in order to prevent a recurrence of what they thought to be an attempt to illegitimately undermine a government elected with an unprecedented popular mandate, this punishment was virtually tantamount to capital punishment.

In a climate, where it was difficult to find employment, dismissal from work meant lack of income, and grave difficulties in carrying on life itself. In the meantime, severe pressures were being exerted on Secretaries to Ministries ‘o fill vacancies immediately. A great deal of time had to be set aside to see government Members of Parliament who were urging the appointment of their nominees to the various vacant positions. For my part, I realized that once these vacancies were filled the door Would have been permanently closed to any of the strikers getting back.

The large majority of those who struck work were not extremists or militants. They were ordinary officers, many of them conscientious and hard working who obeyed the call made by their Trade Unions. There were many, who came out only reluctantly because of the pressures and ostracization involved in not heeding the call to strike. All of them were dismissed.

(Excerpted from In the Pursuit of Governance, autobiography of MDD Pieris) ✍️

Features

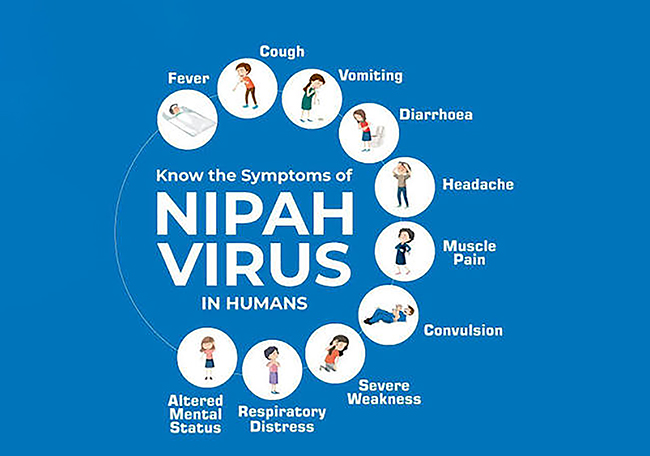

The Silent Shadow: The threat of the Nipah virus in Asia

In the quiet woods of West Bengal and the lush countryside of Kerala, a lethal pathogen is once again testing the limits of modern biosafety. The Nipah virus (NiV), a shadow that has flickered across South and South-East Asia for decades, is currently the subject of heightened international surveillance. With a case fatality rate that can soar up to 75%, this virus Nipah is not just a regional concern; it is a priority pathogen on the World Health Organization (WHO) Research and Development Blueprint, alongside Ebola and COVID-19, due to its epidemic potential.

In the quiet woods of West Bengal and the lush countryside of Kerala, a lethal pathogen is once again testing the limits of modern biosafety. The Nipah virus (NiV), a shadow that has flickered across South and South-East Asia for decades, is currently the subject of heightened international surveillance. With a case fatality rate that can soar up to 75%, this virus Nipah is not just a regional concern; it is a priority pathogen on the World Health Organization (WHO) Research and Development Blueprint, alongside Ebola and COVID-19, due to its epidemic potential.

To understand the much-justified fear Nipah inspires in the scientific community, one needs to look at its molecular machinery. Nipah is a negative-sense, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the genus Henipavirus. In a kind of “Instruction Manual” analogy, Positive-Sense (+RNA) arrive with an instruction manual already written in the cell’s language. As soon as they enter the cell, the cell can start reading the RNA and “printing” viral proteins immediately. In contrast, Negative-Sense (-RNA) viruses like Nipah, Influenza, or Rabies, arrive with an instruction manual that is written backwards or as a “mirror image.” The cell’s machinery cannot read it directly. It cannot dictate terms to the cell. It needs a “translator” to get the cell to do what the virus wants. If the translator is deactivated, the virus becomes inert. However, with the help of the active translator, a replication pathway is created. This specific replication pathway is a major area of study for antiviral drugs. If we can find a way to “jam” that specific viral translator without hurting the host cell’s own functions, we can effectively stop the virus, so to speak, in its tracks.

Nipah is a “Biosafety Level 4” agent; the highest risk category requiring maximum containment. The virus targets the host’s cells lining of blood vessels and the nerve tissues. Once it enters the human body, typically through the binding of its attaching glycoprotein to host receptors, it initiates a devastating cascade. The infection often presents as a dual-threat, namely acute respiratory problems with features of severe “atypical pneumonia,” and potentially fatal involvement of the brain. In its most sinister form, the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier which routinely protects against invasion of the central nervous system by infective organisms, causing massive inflammation of the brain. Symptoms progress rapidly from fever and headache to drowsiness, disorientation, and seizures, often culminating in a coma within 24 to 48 hours.

As of January 2026, the epidemiological map of Asia shows several distinct hotspots. India is currently managing two distinct geographical risks. In West Bengal, a recent cluster in Kolkata and Barasat involving healthcare workers has triggered a massive “trace and test” operation. This region, bordering Bangladesh, has a history of outbreaks dating back to 2001. Simultaneously, Kerala in Southern India has become a recurrent epicentre, with four confirmed cases and two deaths reported in mid-2025 across the Malappuram and Palakkad districts.

Bangladesh remains the most consistently affected nation. In 2025 alone, four fatal, unrelated cases were reported across the Barisal, Dhaka, and Rajshahi divisions. Unlike the hospital-based transmission often seen elsewhere, Bangladesh’s outbreaks are frequently linked to a cultural staple, which is the consumption of raw date palm sap.

The current clusters have sent warning currents across the continent. Airports in Thailand (Suvarnabhumi and Phuket), Nepal, and Singapore have reinstated COVID-style health screenings for travellers arriving from affected Indian states. Taiwan has gone a step further, proposing to categorise Nipah as a “Category 5” notifiable disease; the highest level of public health alert.

The natural reservoir of Nipah is the Pteropus genus of fruit bats, commonly known as flying foxes. These bats carry the virus without falling ill themselves, shedding it in their saliva, urine, and excrement. The “spillover” to humans typically occurs via three routes:

= Contaminated Food: Eating fruit partially consumed by bats or drinking raw date palm sap where bats have urinated into the collection pots.

= Intermediate Hosts: In the 1998 Malaysia outbreak, pigs acted as “amplifying hosts” after eating contaminated fruit, later passing the virus to farmworkers.

= Human-to-Human: This is the greatest concern for urban centres. Close contact with the bodily fluids or respiratory droplets of an infected patient, often enough in a home care or hospital setting, can trigger secondary clusters.

While Sri Lanka has not yet recorded a human case of Nipah, the island cannot afford complacency. The risks are grounded in both biology and regional connectivity. Surveillance studies have confirmed that Pteropus bat species are indigenous to Sri Lanka. While the presence of the bat does not guarantee the presence of the virus, the ecological apparatus for a spillover event exists on the island. Environmental changes, such as deforestation, can drive these bats closer to human settlements in search of food, increasing the probability of contact.

Sri Lanka’s proximity to South India, particularly Kerala and Tamil Nadu, creates a constant flow of people and goods. With direct flights and maritime links to regions currently monitoring outbreaks, the risk of an “imported case” is quite considerable. A single undetected traveller in the incubation period, that is the period between the infection and production of the disease, which can last from 4 to 14 days, and in rare cases up to 45, could theoretically introduce the virus into a local clinical setting.

The primary challenge for Sri Lanka lies in looking at what doctors call a “differential diagnosis”, which looks at all possible conditions that have a similar clinical presentation. Early symptoms of Nipah mimic common tropical illnesses like dengue, Japanese encephalitis, or even severe influenza. Without high-level biocontainment labs (BSL-3 or BSL-4) and rapid Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) testing protocols specifically tuned for Henipaviruses, a localised outbreak could gain significant momentum before it is correctly identified. Incidentally, PCR is a sort of molecular photocopier which allows scientists to take a tiny, almost undetectable amount of viral genetic material (RNA or DNA) from a patient’s swab or blood sample and amplify it millions of times until there is enough to be detected and identified.

Currently, there is no licensed vaccine or specific antiviral drug in the treatment for Nipah. Management is limited to intensive supportive care. However, the “One Health” approach offers a roadmap for prevention:

=For the Public: Ensure all fruits are thoroughly washed and peeled, and discard any fruit that shows signs of bird or animal bites (“bat-bitten” fruit).

=For Healthcare Workers: Strict adherence to Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) measures. Wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) when treating patients with unexplained encephalitis or respiratory distress is vital.

=For Authorities: Strengthening surveillance of bat populations and enhancing the diagnostic capacity of national laboratories.

Nipah virus is a reminder of the permeable borders between the wild and the urban. As Asia watches the current clusters in India and Bangladesh, the lesson for Sri Lanka is clear: preparedness is the only antidote to a virus that currently has no cure.

We need to make the general public well aware of preventive guidelines for travellers to other countries, most particularly for those traveling to or from Kerala, West Bengal, or Bangladesh. Before travel, it is necessary to monitor the Sri Lankan Ministry of Health (Epidemiology Unit) website for travel advisories. Currently, screening is focused on passengers arriving from Kolkata and Kerala. It is essential to ensure that travel insurance covers medical evacuation and high-intensity supportive care, as Nipah management requires ICU facilities.

During the stay in an area of another country that is a high-risk area, avoid “Bat-Bitten” Fruit and do not purchase or consume fruit that has visible puncture marks, scratches, or missing chunks. In regions where fruit bats (Pteropus) are active, they often taste fruit and discard it, leaving saliva and virus behind. It is essential to only eat fruit that you have washed thoroughly with clean water and peeled yourself. Avoid pre-sliced fruit platters in street markets. Stay away from pig farms and bat roosting sites such as large trees where “flying foxes” gather. If you visit rural areas, do not touch surfaces under these trees which may be contaminated with bat urine.

Once a traveller returns to Sri Lanka, the authorities at the ports of entry have to be most vigilant. As for the traveller, it is best to self-monitor for about a month. The incubation period can be long. If you develop a fever, severe headache, or cough within three weeks of returning, isolate yourself immediately. If you seek medical care, the very first thing you should tell the doctor is: “I have recently returned from a region where Nipah cases were reported.”

Healthcare workers have to be extremely careful. This is crucial for doctors and nurses in Sri Lankan Outpatient Departments (OPD) and Emergency Treatment Units (ETUs). Careful medical triage of sorting out possible cases is mandatory. It is necessary to maintain a High Index of Suspicion: In any patient presenting with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) or Encephalitis (confusion, seizures, or coma), immediately check their travel history or contact with travellers. It is essential that the health staff do not rule out Nipah just because a patient has a “simple” cough or a “sore throat” as these often precede the neurological crash by 24–48 hours.

Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) measures have to be employed compulsorily. Because Nipah has a high rate of nosocomial (hospital-acquired) spread, the following “Standard Plus” precautions are mandatory for suspected cases:-

=Meticulous hand hygiene before and after patient contact.

=Use of medical masks and eye protection (goggles or face shields).

=Double gloving and the use of fluid-resistant gowns.

If a patient is suspected to suffer from Nipah virus infection, the patient needs to be moved to a dedicated isolation ward immediately. Do not “cohort” (group) them with other encephalitis or flu patients until Nipah is ruled out by PCR. Treat all bodily fluids (blood, urine, saliva) as highly infectious biohazards. Use 0.5% sodium hypochlorite for surface disinfection. Under the Infectious Diseases Act, Nipah is a notifiable disease in Sri Lanka. Contact the regional Medical Officer of Health (MOH) or the Epidemiology Unit immediately upon suspicion. DO NOT WAIT FOR LAB CONFIRMATION.

One final but absolutely vital and life-saving declaration and truism is that the Nipah virus is very sensitive to common soaps and detergents. Regular handwashing with soap for at least 20 seconds is one of the most effective ways to break the chain of transmission, even for a virus that is this lethal.

Features

India shaping-up as model ‘Swing State’

The world of democracy is bound to be cheering India on as it conducts its 77th Republic Day celebrations. The main reasons ought to be plain to see; in the global South it remains one of the most vibrant of democracies while in South Asia it is easily the most successful of democracies.

The world of democracy is bound to be cheering India on as it conducts its 77th Republic Day celebrations. The main reasons ought to be plain to see; in the global South it remains one of the most vibrant of democracies while in South Asia it is easily the most successful of democracies.

Besides, this columnist would go so far as to describe India as a principal ‘Swing State.’ To clarify the latter concept in its essentials, it could be stated that the typical ‘Swing State’ wields considerable influence and power regionally and globally. Besides they are thriving democracies and occupy a strategic geographical location which enhances their appeal for other states of the region and enables them to relate to the latter with a degree of equableness. Their strategic location makes it possible for ‘Swing States’ to even mediate in resolving conflicts among states.

More recently, countries such as Indonesia, South Africa and South Korea have qualified, going by the above criteria, to enter the fold.

For us in South Asia, India’s special merit as a successful democracy resides, among other positives, in its constitutionally guaranteed fundamental rights. Of principal appeal in this connection is India’s commitment to secularism. In accordance with these provisions the Indian federal government and all other governing entities, at whatever level, are obliged to adhere to the principle of secularism in governance.

That is, governing bodies are obliged to keep an ‘equidistance’ among the country’s religions and relate to them even-handedly. They are required to reject in full partiality towards any of the country’s religions. Needless to say, practitioners of minority religions are thus put at ease that the Indian judiciary would be treating them and the adherents of majority religions as absolute equals.

To be sure, some politicians may not turn out to be the most exemplary adherents of religious equality but in terms of India’s constitutional provisions any citizen could seek redress in the courts of law confidently for any wrongs inflicted on her on this score and obtain it. The rest of South Asia would do well to take a leaf from India’s Constitution on the question of religious equality and adopt secularism as an essential pillar of governance. It is difficult to see the rest of South Asia settling its religious conflicts peacefully without making secularism an inviolable principle of governance.

The fact is that the Indian Constitution strictly prohibits discriminatory treatment of citizens by the state on religious, racial, caste, sex or place of birth grounds, thus strengthening democratic development. The Sri Lankan governing authorities would do well to be as unambiguous and forthright as their Indian counterparts on these constitutional issues. Generally, in the rest of South Asia, there ought to be a clear separation wall, so to speak, between religion and politics.

As matters stand, not relating to India on pragmatic and cordial terms is impossible for almost the rest of the world. The country’s stature as a global economic heavyweight accounts in the main for this policy course. Although it may seem that the US is in a position to be dismissive of India’s economic clout and political influence at present, going forward economic realities are bound to dictate a different policy stance.

India has surged to be among the first four of global economic powers and the US would have no choice but to back down in its current tariff strife with India and ensure that both countries get down to more friction-free economic relations.

In this connection the EU has acted most judiciously. While it is true that the EU is in a diplomatic stand-off of sorts with the US over the latter’s threat to take over Greenland and on questions related to Ukraine, it has thought it best to sew-up what is described as an historic free trade agreement with India. This is a truly win-win pact that would benefit both parties considering that together they account for some 25 percent of global GDP and encompass within them 3 billion of the world’s population.

The agreement would reduce trade tariffs between the states and expand market access for both parties. The EU went on record as explaining that the agreement ‘would support investment flows, improve access to European markets and deepen supply chain integration’.

Besides, the parties are working on a draft security and defence partnership. The latter measure ought to put the US on notice that India and the EU would combine in balancing its perceived global military predominance. The budding security partnership could go some distance in curbing US efforts to expand its power and influence in particularly the European theatre.

Among other things, the EU-India trade agreement needs to be seen as a coming together of the world’s foremost democracies. In other words it is a notable endorsement of the democratic system of government and a rebuffing of authoritarianism.

However, the above landmark agreement is not preventing India from building on its ties with China. Both India and China are indicating in no uncertain terms that their present cordiality would be sustained and further enriched. As China’s President Xi observed, it will be a case of the ‘dragon and the elephant dancing together.’

Here too the pragmatic bent in Indian foreign policy could be seen. In economic terms both countries could lose badly if they permit the continuation of strained ties between them. Accordingly, they have a common interest in perpetuating shared economic betterment.

It is also difficult to see India rupturing ties with the US over Realpolitik considerations. Shared economic concerns would keep the US and India together and the Trump administration is yet to do anything drastic to subvert this equation, tariff battles notwithstanding.

Although one would have expected the US President to come down hard on India over the latter’s continuing oil links with Russia, for instance, the US has guarded against making any concrete and drastic moves to disrupt this relationship.

Accordingly, we are left to conclude from the foregoing that all powers that matter, whether they be from the North or South, perceive it to be in their interests to keep their economic and other links with India going doubly strong. There is too much to lose for them by foregoing India’s friendship and goodwill. Thus does India underscore its ‘Swing State’ status.

Features

Securing public trust in public office: A Christian perspective – Part III

Professor, Dept of Public & International Law, Faculty of Law, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka and independent member, Constitutional Council of Sri Lanka (January 2023 to January 2026)

This is an adapted version of the Bishop Cyril Abeynaike Memorial Lecture delivered on 14 June 2025 at the invitation of the Cathedral Institute for Education and Formation, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

(Continued from yesterday)

Conviction

I now turn to my third attribute, which is conviction. We all know that we can have different types of convictions. Depending on our moral commitments, we may think of convictions as good or bad. From the Bible, the convictions of Saul and the contrasting convictions of Paul (Saul was known as Paul after his conversion) provide us with an excellent illustration of the different convictions and value commitments we may have. As Christians we are required to be convinced about the values of the Kingdom of God, such as truthfulness and rationality, the first and second attributes that I spoke of. We are also called to act, based on our convictions in all that we do.

I used to associate conviction with fearlessness, courage or boldness. But in the last two to three years of my own life, I have had the opportunity to think more deeply about the idea of conviction and, increasingly, I am of the view that conviction helps us to stand by certain values, despite our fears, anxieties or lack of courage. Conviction forecloses possibilities of doing what we think is the wrong thing or from giving up. Recall here the third example I referred to, of Lord Wilberforce and his efforts at abolishing the slave trade and slavery. He had to persevere, despite numerous failures, which he clearly did. In my own experiences, whether at the university or at the Constitutional Council, failures, hopelessness, fear or anxiety are real emotions and states of mind that I have had to deal with. In Sri Lanka, if convictions about truth, rationality and justice compel a public official to speak truth to power and act rationally, chances are that such public official has gone against the status quo and given people with real human power, reason to harm them. Acting out of conviction, therefore, can easily give rise to a very human set of reactions – of fear for oneself and for one’s family’s safety, anxiety about grave consequences, including public embarrassment and, sometimes, even regret about taking on the responsibilities that one has taken on. In such situations, such public officials, from what I have noticed, do not ever regret acting out of conviction, but rather struggle with the implications and the consequences that may follow.

When we consider the work of Lord Wilberforce, Lalith Ambanwela and Thulsi Madonsela we can see the ways in which their convictions helped them to persist in seeking the truth, in remaining rational and in seeking justice. They demonstrate to us that conviction about truth and justice pushes and even compels us to stand by those ideals and discharge our responsibilities in a principled and ethical way. Convictions help us to do so, even when the odds are stacked against us and when the status quo seems entrenched and impossible to change. This is well illustrated in how Wilberforce persisted with his attempts at law reform, despite the successive failures.

Importantly, some public officials saw the results of acting out of conviction in their lifetime, but others did not. Wilberforce saw the results of his work in his lifetime. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a German theologian who opposed Hitler’s rule, was executed, by hanging, by the Nazi German state, a couple of weeks before Hitler committed suicide. Paul spent the last stage of his life as a prisoner of the Romans and was crucified. These examples suggest that conviction compels us to action, regardless of our chances of success, and for some of us, even unto death. Yet, conviction gives us hope about the unknown future. Conviction, indeed, is a very powerful human attribute.

I will not go into this, but the Christian faith offers much in terms of how a public official may survive in such difficult situations, as has been my own experience thus far.

Critical Introspection

I chose critical introspection as the fourth attribute for two reasons. One, I think that the practice of critical introspection by public officials is a way of being mindful of our human limitations and second it is a way in which we can deepen and renew our commitment to public service. Critical introspection, therefore, in my view, is essential for securing public trust and it is an attribute that I consider to be less and less familiar among public officials.

In Jesus, and in the traditions of the Church, we find compelling examples of a commitment to critical introspection. During his Ministry, he was unapologetic about taking time off to engage in prayer and self-reflection. He intentionally went away from the crowds. His Ministry was only for three years and he was intentional about identifying and nurturing his disciples. These practices may have made Jesus less available, perhaps less ‘productive’ and perhaps even less popular. However, this is the approach that Jesus role-modelled and I would like to suggest to you today, that there is value in this approach and much to emulate. Similarly, the Biblical concept of the Sabbath has much to offer to public officials even from a secular perspective in terms of rest, stepping away from work, of refraining from ‘doing’ and engaging with the spiritual realm.

Importantly, critical introspection helps us to anticipate that we are bound to make mistakes. no matter how diligent we may be and of our blind spots. Critical introspection creates space for truth, rationality and conviction to continue to form us into public officials who can secure public trust and advance it.

In contrast, I have found, in my work, that many embrace, without questioning, a relentless commitment to working late hours and over the weekends. This is, of course, at the cost of their personal well-being, and, equally importantly, of the well-being of their families. Relentless hard work, at the cost of health and personal relationships, is commonly valorised, rather than questioned, from what I can see, ironically, even in the Church.

One of the greatest risks of public officials not engaging in critical introspection is that they may lose the ability to see how power corrupts them or they may end up taking themselves too seriously. I have seen these risks manifest in some public officials that I work with – power makes them blind to their own abuse of power and they consider themselves to be above others and beyond reproach.

Where a public official does not practice critical introspection, the trappings of public office can place them at risk of taking themselves too seriously and losing their ability to remain service-oriented. Recall the trappings of high constitutional office – the security detail, the protocol and sometimes the kowtowing of others. It is rare for us to see public officials who respond to these trappings of public office lightly and with grace. Unfortunately for us, we have seen many who thrive in it. In my own work, I have come across public officials who are extremely particular about their titles and do not hesitate to reprimand their subordinates if they miss addressing them by one of their titles. Thankfully, I also know and work with public officials who are most uncomfortable with the trappings of public office and suffer it while preserving their attitude of humility and service.

Permit me to add a personal note here. In April 2022 a group of Christians and Catholics decided to celebrate Maundy Thursday by washing the feet of some members of the public. I was invited to come along. On that hot afternoon, in one corner of public place where people were milling about, the few of us washed the feet of some members of the public, including those who maintain the streets of Colombo. I do not know what they thought of our actions but I can tell you how it made me feel. The simple act of kneeling before a stranger and one who was very obviously very different to me, and washing their feet, had a deep impact on me. Many months later, when I was called, most unexpectedly, to be part of Sri Lanka’s Constitutional Council and had to struggle through that role for the better part of my term, that experience of washing feet of member of the public became a powerful and personal reminder to me of the nature of my Christian calling in public service. I do think that the Christian model of servant leadership has much to offer the world in terms of what we require of our public officials.

Compassion

Due to limitations of time, I will speak to the fifth attribute only briefly. It is about compassion – an aspect of love. Love is a complex multi-dimensional concept in Christianity and for today’s purposes, I focus on compassion, an idea that is familiar to our society more generally in terms of Karuna or the ability to see suffering in oneself and in others. The Gospels, at one point, record that when Jesus saw the crowds that he was ministering to, that he had compassion on them.

Of course, we know that the people are not always mere innocent victims of the abuse of power but can be active participants of the culture of patronage and corruption in our society. Nevertheless, for public officials to secure public trust, I think compassion, is essential. Compassion, however, is not about bending the rules, arbitrarily, or about showing favouritism, based on sympathy. In Sri Lanka we are hard pressed to find examples of compassion by public officials, at high levels, despite the horrors we have experienced in this land. However, in the everyday and at lower layers of public service, I do think there are powerful acts of compassion. An example that has stayed with me is about an unnamed police officer who is mentioned in the case of Yogalingam Vijitha v Wijesekera SC(FR) 186/2001 (SC Minutes 28 August 2002). In 2001, Yogalingam Vijitha was subject to severe forms of sexual torture by the police. After one episode of horrific torture, including the insertion of the tip of a plaintain-flower dipped in chilli to her vagina, the torturers left her with orders that she should not be given any water. This unnamed police officer, however, provided her with the water that she kept crying out for. In a case which records many horrific details about how Yogalingam Vijitha was tortured, this observation by the Court, about the unnamed police office, stands out as a very powerful example of compassion in public office.

Compassion for those who seek our services whether at university, at courts or at the kachcheri, should be an essential attribute for public officials.

Aspects not explored

There is much more that can be said about what a Christian perspective has to offer in terms of securing public trust in public office but due to limitations of time, I have only spoken about truthfulness, rationality, conviction, critical introspection and compassion – and that, too, in a brief way. I have not explored today several other important attributes, such as the Christian calling to prioritise the vulnerable and the Christian perspectives on confession, forgiveness and mercy that offers us a way of dealing with any mistakes that we might make as public officials. I have also not spoken of the need for authenticity – public officials ought to maintain harmony in the values that they uphold in their public lives with the values that they uphold their personal lives, too. Finally, I have not spoken of how these attributes are to be cultivated, including about the responsibility of the Church in cultivating these attributes, practice them and about how the Church ought to support public officials to do the same.

Securing Public Trust

Permit me to sum up. I have tried to suggest to you that cultivating a commitment to truthfulness, rationality, conviction about the values of public service, critical introspection and compassion – are essential if public officials are to secure public trust.

The crisis of 2022 is a tragic illustration of the pressing need in our society to secure trust in public office. In contrast, the examples of Thulsi Madonsela, former Public Protector of South Africa, of late Lalith Ambanwela, former Audit Superintendent from Sri Lanka and Lord Wilberforce illustrate that individual public officials who approach public service can and have made a significant difference, but, of course, at significant personal cost. Given the mandate of this memorial lecture, I drew from the Christian faith to justify and describe these five attributes. However, I do think that a similar secular justification is possible. Ultimately, secular or faith-based, we urgently need to revive a public and dynamic discourse of our individual responsibilities towards our collective existence, including about the ways in which can secure public trust in public office. I most certainly think that the future of our democracy depends on generating such a discourse and securing the trust of the public in public office.

If any of you here have been wondering whether I am far too idealistic or, as some have tried to say, ‘extreme’ in the standard that I have laid out for myself and others like me who hold public office – I will only say this. Most redeeming or beautiful aspects of our human existence have been developed mostly because individuals and collectives dared to dream of a better future, for themselves and for others. Having gone through what has easily been the toughest two-three years of my life, I know that, here in Sri Lanka, too, we have among us, individuals and collectives who dare to dream of a better future for this land and its peoples – and they are making an impact. Three years ago, you could have dismissed what I have had to say as being the musings of an armchair academic – but today, given my own experiences in public office with such individuals who have dared to dream of a better future for us, I can confidently tell you – these are not mere musings of an armchair academic but rather insights drawn from what I have been witness to.

(Concluded)

by Dinesha Samararatne

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoComBank, UnionPay launch SplendorPlus Card for travelers to China

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoComBank advances ForwardTogether agenda with event on sustainable business transformation

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoConference “Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority Bill: Neither Here, Nor There”

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoLuck knocks at your door every day

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDialog Brings the ICC Men’s T20 Cricket World Cup 2026 Closer to Sri Lankans

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoRising climate risks and poverty in focus at CEPA policy panel tomorrow at Open University

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoBourse positively impacted by CBSL policy rate stance