Opinion

US double standards displayed by Ambassador Chung:

Draconian Patriot Act exposed

By Daya Gamage

Foreign Service National Political Specialist (ret)

U.S. Department of State

Six weeks after the September 11 attacks on American soil, the U.S. Congress passed the “USA/Patriot Act,” nation’s hurried surveillance laws that expanded the government’s authority to check on its own citizens, while simultaneously reducing checks and balances on those powers like judicial oversight, public accountability, and the ability to challenge government searches in court.

The Senate version of the Patriot Act was sent to the floor with no discussion, debate, or hearings. In the House, hearings were held, and a carefully constructed compromise bill emerged with no debate or consultation with rank-and-file members, the House leadership threw out the compromise bill and replaced it with legislation that mirrored the Senate version. Neither discussion nor amendments were permitted, and once again members barely had time to read the bill before they were forced to cast a vote on it.

It should be mentioned that all the obnoxious provisions of the USA PATRIOT ACT were in operation until the promulgation of the Freedom Act of 2015: long fifteen years. In fact, some provisions were preserved in the Freedom Act.

Before I present the draconian provisions of the USA/Patriot Act, it should be noted here how the U.S. Ambassador Julie Chung – when having a discourse with Justice Minister Wijayadasa Rajapakshe – had “expressed her strong desire”, of course on behalf of Washington policymakers, “to see extensive discussions, both public and parliamentary” on Sri Lanka’s proposed Anti-Terrorism Bill which is envisaged to replace the current Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA).

In a Twitter feed, Ms. Chung referring to what was discussed during that meeting with Minister Rajapakshe on 20 April, noted her concerns with regard to certain aspects of the proposed Bill which fall outside of international standards.

She further highlighted that it is important that “all voices – including civil society, academia, and lawmakers – are considered to ensure the legislation serves as an effective tool for combating terrorism without restricting freedom of expression or assembly.”

These disgraceful double-standards of Washington policymakers and lawmakers – and of course their overseas diplomats – in dealing with Sri Lanka’s ‘national issues’ since the advent of the separatist war in the north and the insurrection in the south in the 1980s are now very broadly dealt with by two personnel who worked within the U.S. Department of State for thirty years in the area of foreign affairs: One is this writer who is a retired Foreign Service National Political Specialist once accredited to the Political Section of the U.S. Embassy in Colombo, and the other, Dr. Robert K. Boggs, a retired Senior Foreign Service (FS) and Intelligence Officer who served as Political Counselor at the Colombo Mission with a very broad knowledge of India’s ‘role’ in Sri Lanka. Their manuscript ‘Defending Democracy: Lessons in Strategic Diplomacy from U.S.-Sri Lankan Relations” is nearing completion with alarming disclosures, provocative analyses and interpretations based on their up-close and personal knowledge and understanding how Washington used ‘double standards’ in handling its foreign relations reducing Sri Lanka to some level of a client state. Sri Lanka’s own infantile behaviour dealing with her foreign relations since the 1980s contributed too to become a client state allowing ‘national issues’ to become ‘global’ ones.

When Ambassador Chung ‘advice’ the Sri Lanka government – through its Justice Minister – to undertake a wider and broad scrutiny of the proposed anti-terrorism legislation, Washington’s ‘double-standards’ are well exposed when our memory goes back to the manner in which it steamrolled the USA PATRIOT ACT in September 2001 documented above.

This writer doesn’t see any Sri Lankan lawmaker questioning Ambassador Julie Chung, purposely ignoring the manner in which the USA/Patriot Act came into America’s statute books with draconian features, enforced for fifteen years until the Freedom Act was brought in.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) had expressed that the “Congress and the Administration acted without any careful or systematic effort to determine whether weaknesses in our surveillance laws had contributed to the attacks, or whether the changes they were making would help prevent further attacks. Indeed, many of the act’s provisions have nothing at all to do with terrorism”.

The USA PATRIOT ACT increased the government’s surveillance powers in four areas:

Records searches. It expands the government’s ability to look at records on an individual’s activity being held by third parties. (Section 215)

Secret searches. It expands the government’s ability to search private property without notice to the owner. (Section 213)

Intelligence searches. It expands a narrow exception to the Fourth Amendment that had been created for the collection of foreign intelligence information (Section 218).

“Trap and trace” searches. It expands another Fourth Amendment exception for spying that collects “addressing” information about the origin and destination of communications, as opposed to the content (Section 214).

It is frustrating to remind Ambassador Julie Chung, and Washington policymakers who guide her, the undemocratic features in the US anti-terrorism act when she uses ‘double standards’ – as Washington always engage dealing with international affairs of which very broadly analysed in Robert Boggs-Daya Gamage’s forthcoming book – to advocate that there exist certain provisions in the Sri Lanka-proposed Anti-Terrorism Bill ‘outside of international standards’.

When the Bush administration brought the Patriot Act, it had scant regard for ‘international standards’.

There are three overlying undemocratic aspects of the Patriot Act: torturing suspects, indefinite holding of suspects, and spying on citizens.

How did Washington round-up Sri Lanka government during Ranil Wickremasinghe’s premiership at the turn of this century to engage in torture in “third-party countries” that were not part of the Geneva Convention? Do we have to remind Ambassador Julie Chung of this?

During the 2002-2004 peace negotiations, (between the Sri Lanka government and LTTE mediated by Norway and the U.S. directly involving in it) Washington did not scruple to use its influence to persuade the Wickremasinghe’s Government, which had foreign and defence portfolios under it, to help the U.S. avoid accountability before the International Criminal Court (ICC). In the fall of 2002 various State Department officials pressed Prime Minister Wickremesinghe repeatedly to sign a bilateral agreement under Article 98 of the Rome Statute, the treaty that in 1998 established the ICC. Under the treaty, such a bilateral agreement would immunise the citizens of each signatory state from being surrendered by the other to the jurisdiction of the (ICC) Court. The Wickremasinghe government did sign such an agreement in November 2002.

It was not coincidental that in October 2002 the U.S. and coalition partners launched a “shock and awe” bombing campaign and invasion of Iraq as part of the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT). At the same time, more than 9000 U.S. troops were battling Taliban militants in Afghanistan. The Bush administration clearly wanted to shield U.S. soldiers from ICC prosecution for inevitable charges of war crimes. In a report in 2016 the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor found “a reasonable basis to believe” that since May 2003 “at least 54 detained persons” in Afghanistan were subjected to grave crimes by U.S. armed forces, including “the war crimes of torture and cruel treatment.” The same report further alleged that from 2003 to 2004 members of the CIA committed grave crimes, including “rape and/or sexual violence” against “at least 24 detained persons” in Afghanistan and other states. Measures taken by Washington to protect its combatants abroad from criminal accountability are particularly questionable in light of subsequent USG pressure on Sri Lanka–a signatory of an Article 98 agreement–to submit to international investigations for war crimes. U.S. hypocrisy and double-standards well displayed.

In August 2003 Prime Minister Wickremasinghe covertly authorized the USG’s use of Sri Lankan airspace and Bandaranaike International Airport (BIA) for Washington’s so-called “extraordinary rendition and detention programme.” This meant that the CIA could use the airport for the transfer of prisoners to the custody of other foreign governments or to secret CIA prisons outside the U.S. known as “black sites.” Washington engaged in this practice when in fact, extraordinary rendition and detention is clearly prohibited by the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Forms of Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment.

There were at least two flights during June and August 2003 that used BIA to transport terrorist suspects. One flight operated by Richmor Aviation (a company that operated flights for the CIA for extraordinary rendition) is known to have landed in Sri Lanka during June 19-20, 2003 shortly after the apprehension in central Thailand of Mohammed Farik Bin Amin, alias Zubair Zaid, a Malaysian who is alleged to have been a senior member of Jemaah Islamiyah and al Qaeda. Documents inspected by this writer and his co-author Robert Boggs for their manuscript show that another Richmor aircraft flew from Washington, DC to Bangkok, and then transited BIA on August 13-14 before flying on to Afghanistan, Dubai and Europe. That flight coincided with the capture in Thailand of alleged Indonesian terrorist leader Riduan Isamuddin (a.k.a. Hambali) and Malaysian Mohammed Nazir Bin Lep, (a.k.a. Lillie). All three of these men reportedly were later detained and interrogated at CIA black sites and were later transferred to U.S. custody at Guantanamo Bay. Also in August 2002, the Sri Lanka government arrested a person wanted by the U.S. who was hiding in Sri Lanka and handed him over to the CIA.

The above is to remind Ambassador Chung of the manner in which Washington executed the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) when she and her Washington-guided policymakers engage in ‘double-standards’ in ‘advising’ Sri Lanka how to draft ‘terrorism legislation’ to ‘keep with international standards’.

Section 802 of the USA PATRIOT ACT made domestic terrorists subject to the same punishments (torture) as international terrorists and defined domestic terrorism as: “An act dangerous to human life” that is a violation of the criminal laws of a state or the United States, if the act appears to be intended to: (i) intimidate or coerce a civilian population; (ii) influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or (iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination or kidnapping.”

The Patriot Act allowed for spying by the United States government on everyday people without warrant, by means of Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Courts and direct legislation.

The American Civil Liberties Union points out how judicial review or oversight lacked under the Patriot Act: “Judicial oversight of these new powers is essentially non-existent. The government must only certify to a judge – with no need for evidence or proof – that such a search meets the statute’s broad criteria”.

Both domestically and internationally, the Patriot Act set a precedent of undemocratic legislation to prevent terrorism through violations of civil liberties. Through direct amendments and in conjunction with “brother bills,” the Patriot Act allowed for, pushed, and resulted in more undemocratic legislation, ultimately resulting in the US Congress-ratified Freedom Act of 2015.

The first major direct modification was the USA PATRIOT Act Improvement and Reauthorization Act of 2005, which made 14 provisions permanent and extended several controversial sections until 2009, such sections as: 206, which allowed the National Security Agency (NSA) to access FISA Courts and to wiretap any communication of a suspect; the other is Section 215, which allowed the NSA to collect every phone call made to and from the United States; and provisions from the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, which “permitted the FISA Court to authorize surveillance and physical searches aimed at foreign nationals who are ‘engaged in international terrorism or activities in preparation for international terrorism”‘.

The biggest specific precedent created by the Patriot Act was the direct transition to the USA Freedom Act of 2015, which corrected some of the abuses allowed by the Patriot Act, but left others unchecked. Many of the major provisions of the Patriot Act were set to expire that year and instead of renewing them, the government introduced a new bill with less controversy. Drafters of the bill claimed that the government could only access certain data after submitting public requests to the FISA Court, marking a big difference from the Patriot Act. In 2015, a few major sections of the Patriot Act were set to expire, including Sections 206 and 215 mentioned above. Even without the Freedom Act, the legality of Section 215 was headed to the Courts regardless, as the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled that the Patriot Act was not enough justification to allow bulk metadata collection (Patriot Act 2017). Luckily, it never had to go farther because Congress scrapped the Patriot Act and got partially rid of that section, but the Freedom Act is by no means innocent of civil liberties violations.

Does Ambassador Julie Chung get it? And does Justice Minister Rajapaksha comprehend?

This clearly shows how the USA PATRIOT ACT of 2001 was in operation for a full fifteen years until certain changes were made in the Freedom Act of 2015.

As described recently by CNN International socio-political news presenter Fareed Zakaria:

“America’s unipolar status has corrupted the country’s foreign policy elite. Our foreign policy is all too often an exercise in making demands and issuing threats and condemnations. There is very little effort made to understand the other side’s views or actually negotiate. . . . All this evokes the inertia of an aging empire. Today, our foreign policy is run by insular elite that operates by mouthing rhetoric to please domestic constituencies—and seems unable to sense that the world out there is changing, and fast.” (xA)

The study undertaken by this writer and his co-author Dr. Robert Boggs should help readers to decide to what extent Zakaria’s troubling diagnosis is accurate and, if so, whether the U.S.-Sri Lanka experience offers relevant lessons for remedial action.

This writer’s intention is to underscore Washington’s double standards – well reflected by its ambassador recently when in conversation with Justice Minister Wijayadasa Rajapakshe – to bring some sense to authorities in Colombo.

At the time that the United States was pressuring Colombo to accept “national, international, and hybrid mechanisms to clarify the fate and whereabouts of the disappeared,” the USG had not itself ratified the UN convention of 2006 requiring state party to criminalize enforced disappearances and take steps to hold those responsible to account. Despite a resolution passed by the U.S. House of Representatives on November 19, 2020 calling on the USG to ratify the international convention, this still has not happened. The U.S.’ long history of rejecting accountability is strongly rooted in legislation.

The American Service-Members Protection Act (ASPA) was an amendment to the 2002 Supplemental Appropriations Act (H.R. 4775) passed in response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the launch of the so-called Global War on Terror. The ASPA aims to “protect U.S. military personnel and other elected and appointed officials of the Government against prosecution by an international criminal court to which the U.S. is not a party.” Among other defensive provisions the Act prohibits federal, state and local governments and agencies (including courts and law enforcement agencies) from assisting the International Criminal Court in The Hague. It even prohibits U.S. military aid to countries that are parties to the Court. As mentioned above, In 2002, during the administration of Prime Minister Wickremesinghe, the GSL signed with the U.S. an “Article 98 Agreement,” agreeing not to hand over U.S. nationals to the Court.

Washington and its ambassador in Colombo continue to engage in hypocrisy and double-standards when all this evidence is available in the public domain.

(The writer is a retired Foreign Service National Political Specialist of the U.S. Department of State once accredited to the Political Section of the U.S. Embassy, Sri Lanka)

Opinion

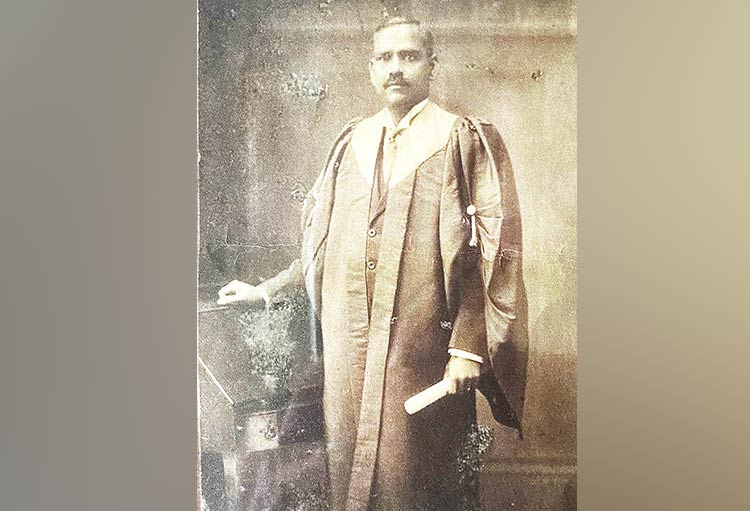

Dr Don Robert Seneviratne

My father Don Robert Seneviratne was born in 1887. Having had his early education at Prince of Wales College, Moratuwa, he entered the Medical School in Colombo and passed out with a LMS (Licentiate of Medical School). After a few years he proceeded to the Universities of Edinburgh and Glasgow earning their Licentiates.

When he returned to Ceylon and to his birthplace Kaluwana in Homagama, he was warmly welcomed by the people as being the first person from the village to have gone abroad and qualified in the UK. My mother recalled that he was welcomed by pandals of plaintain trees.

After a long tenure in government service as a District Medical Officer in places like Deniyaya, Elpitiya, Pimbura and Galle where he served as Judicial Medical Officer, he was appointed Police Surgeon to the Police Department in Colombo. He died suddenly in 1946 after a heart attack and was accorded a Police funeral.

This is a very belated tribute to my father. Whatever I am today and whatever I may have achieved in life is due to the very close and devoted upbringing given to me by my father and my mother, Laura Seneviratne.

May they both attain the Supreme Bliss of Nibbana.

Nihal Seneviratne

Opinion

How to write a research paper

Key Steps and Best Practices

BY Gamini Keerawella

Conducting research and writing a research paper are distinct yet interdependent exercises. In the Social Sciences, a single research project can yield multiple papers, each exploring different dimensions of the central inquiry. A well-executed research project does not automatically translate into a well-crafted research paper. Writing is an art—one that requires practice, patience, and a structured approach. Transforming research findings into a coherent, compelling, and readable paper demands adherence to established methodologies and best practices. Over time, researchers have identified key steps that capture best practices, ensuring clarity, logical flow, and academic integrity. This essay outlines these essential steps for effectively structuring and producing a research paper. However, this should not be taken as a rigid straitjacket; rather, it serves as only a guide to writing a research paper. Before writing your essay, it is essential to identify your main audience. Additionally, the structure of your research paper may require slight adjustments depending on where it will be presented. Many annual research conferences organised by Sri Lankan universities follow a rigid, standardised format, requiring you to fit your content accordingly. However, my focus here is to provide guidelines for writing research articles intended for research journals and the academic sections of newspapers, where writers have more freedom to develop their ideas and structure their content.

Title of Research Paper

The first step in writing a research paper is selecting an appropriate title to align with the scope and central argument of the paper. In turn, a well-crafted title serves as a guiding framework, helping to structure paper’s arguments effectively. When formulating a title, clarity and precision should be the primary focus. It is important to use clear, straightforward language and avoid jargon or overly complex terminology in title that might confuse readers. Additionally, the title should be concise—an excessively long title can dilute the focus, while an overly short one may lack essential details. A compelling title should capture the reader’s interest and encourage further exploration of the paper. Depending on the nature of the research, the title can be framed as a statement or a question, capable of stimulating curiosity and prompting engagement with the content.

Objective of the Paper

First and foremost, you must have a clear understanding of the paper’s objective(s). The next step in writing a research paper is clearly presenting the research question/issue that you are going to explore. If the issue is too broad, the paper may turn into a general essay; if too narrow, it may not give you necessary depth to develop a strong argument. Striking a balance is essential. This step is crucial as it distinguishes research essay from a general essay. A well-defined research problem provides direction for the study by establishing its scope—determining what aspects will be covered and what will be excluded. Rather than simply restating the central research problem, focus on identifying and refining a specific question that your paper aims to address. It is imperative that the research problem be clear, precise, and researchable, enabling systematic investigation and meaningful analysis. Additionally, it is essential to briefly explain the significance of the problem—why it is being raised, and its contribution to the existing body of knowledge. A well-defined research problem not only justifies the study but also provides a strong foundation for developing a compelling argument and drawing evidence-based conclusion

Concepts

When writing a research paper, it is essential to have a clear understanding of the analytical concept that forms the foundation of your argument. Analytical/theoretical concepts will help you to organise your evidence and develop your argument. The level of detail and the way you introduce this concept will depend on your target audience and the nature of your subject matter. Your research may either develop a new analytical framework or test the validity of an existing concept through empirical data. In either case, offering a concise overview of the core idea behind the concept is crucial. This helps establish a solid analytical foundation for your argument and ensures that readers can follow the reasoning that underpins your research. Providing such context also allows for a more meaningful engagement with the data and enhances the overall coherence of your study. Depending on your research focus and publication venue, you may briefly outline your data collection methods.

Scope/Parameters of the Paper

In a research paper, you are not supposed to cover every thing related to the topic. It is essential to clearly define the scope in alignment with the paper’s objectives, as this is fundamental to a focused and coherent analysis. The scope outlines the boundaries of the essay; what aspects will be covered and what will be excluded. This helps in maintaining clarity, avoiding unnecessary diversions, and ensuring that the study remains aligned with its intended purpose. The parameters vary according to the objective (research problem) and the subject mater of the paper. It is essential to have a clear idea of the extent to which the paper will examine its core themes, concepts, or issues. You need to decide whether the focus is theoretical, empirical, or policy-oriented or hybrid. Depending on the research it is better to indicate the period under study, whether it spans a specific historical timeframe. Clearly stating what aspects will not be covered—and justifying these exclusions—helps set realistic expectations for readers while acknowledging constraints such as data availability, methodological limitations, or thematic relevance. Defining the scope with precision ensures that the analysis remains structured and aligned with the core research questions.

Structure into Main Sections/Parts

Once you have precisely defined the scope of your paper and clarified the key concepts, the next crucial step is organising it into well-structured sections. Dividing your paper into clear parts strengthens its structure, enhances readability, and ensures logical argumentation. Outlining the main sections at the beginning helps guide the reader and sets clear expectations. The number of parts will depend on the scope of the paper. However, excessive segmentation can overwhelm the reader and disrupt coherence. It is essential to strike a balance, ensuring each section serves a distinct purpose without unnecessary fragmentation. Each section should logically build on the previous one, reinforcing the central thesis while maintaining clarity. A well-organised structure ensures that every section contributes meaningfully to the argument, enhancing both clarity and persuasiveness.

Subheadings

A key element of a research essay is the use of subheadings in major sections. Subheadings structure a research paper by breaking main sections into manageable parts, improving logical flow and guiding the reader through the content. Well-crafted subheadings enhance coherence by ensuring smooth transitions between ideas and maintaining a clear organisational hierarchy. They enhance the readability of the paper by providing a clear sense of what each subsection covers. To be effective, subheadings should be thoughtfully designed, directly connected to the main heading, and reflective of the paper’s structure. A strong subheading is both descriptive and aligned with the section’s content, improving clarity and readability. By using subheadings strategically, a research paper becomes more accessible, well organized, and engaging for the reader.

Building Argument

The most important aspect of a research paper is the construction of a clear and compelling argument. Unlike a general essay, which often serves a descriptive purpose, a research paper is fundamentally analytical and seeks to establish a position on a specific issue. This requires not only a logical structure but also a deliberate effort to develop an argument step by step.

A well-structured paper does not automatically make for a strong research paper. Structure serves as a framework for presenting an argument cogently, but it is the depth of reasoning, coherence of ideas, and evidence-based support that determine the strength of the argument. Without a clear argument, even the most well organised paper remains ineffective.

A research paper does not aim to cover every possible aspect of a subject. Instead, it requires a focused approach, identifying a specific issue or problem that is outlined at the outset. This issue forms the foundation of the argument, guiding the research and analysis. Building an argument is a step-by-step process. The argument must stem from a clearly defined research question or problem statement. Understanding previous explanations or theories related to the issue helps situate the argument within the broader discourse. The paper must take a clear stance—whether by introducing a new perspective or challenging an existing one. Logical reasoning, empirical data, and theoretical insights must be used to substantiate claims. The argument must be developed progressively, ensuring that each section builds upon the previous one in a logical sequence.

Presenting information alone does not constitute a research essay; rather, research is about constructing a well-reasoned argument. Whether by advancing a new explanation or critically engaging with existing ones, argumentation lies at the heart of scholarly inquiry. A structured approach enhances clarity, but the true strength of a research paper depends on the depth of its argument and the rigor of its analysis. Research does not always require formulating an entirely new argument; at times, critically examining and questioning prevailing explanations drive scholarly progress. Challenging an established thesis can pave the way for academic breakthroughs.

Organising Evidence

The strength and validity of an argument depend on how effectively one presents evidence to support it. Organizing evidence in a coherent manner is, therefore, a fundamental aspect of a research essay. Without sufficient and well-structured evidence, mere interpretation risks being perceived as opinionated rhetoric rather than rigorous academic analysis. Conversely, evidence without interpretation remains sterile and directionless. A well-balanced integration of evidence and interpretation is the hallmark of sound scholarship.

Beyond the mere presence of evidence, its organisation and presentation are equally crucial in strengthening an argument. In critically examining and presenting evidence, two key factors must be considered: authenticity and relevance. Authenticity ensures that the evidence is credible and verifiable, while relevance determines its applicability to the specific focus of the paper. The relevance of evidence is contingent on the research question; therefore, selecting appropriate supporting materials is essential.

Relying on a single piece of evidence is a novice mistake, as it weakens the foundation of an argument, leaving it vulnerable to scrutiny. While a primary or principle piece of evidence may serve as the central pillar of the argument, it must be substantiated with supplementary and corroborative evidence. This layered approach not only reinforces the argument but also demonstrates a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter.

Additionally, presenting counter-evidence—evidence that supports opposing interpretations—is an effective scholarly practice. Engaging with alternative explanations and refuting them through critical analysis enhances the credibility of the argument, showcasing a well-rounded and intellectually rigorous approach. A research essay, therefore, is not merely about advocating a viewpoint but about engaging with evidence in a nuanced and methodical manner to construct a compelling, defensible argument.

Language Clarity

Language is the primary vehicle for communicating structured thoughts and research findings. The clarity, precision, and coherence of writing directly impact how effectively arguments are conveyed and understood. A well-articulated argument, supported by clear and logical reasoning, strengthens the credibility of scholarly work. Conversely, ambiguity, redundancy, or poor organisation can undermine even the most compelling research.

In academic discourse, language is not just a tool but also a benchmark for evaluating scholarly work. Clarity and precision in writing are crucial for publication, as journals expect adherence to strict linguistic and stylistic standards. Academic writing defined by its formal structure, evidence-based reasoning, and objective tone, demands conciseness and readability. Frugal word use prevents redundancy and sharpens arguments, ensuring ideas remain clear and impactful.

For non-native English speakers, writing in English demands careful attention to linguistic accuracy and coherence. Since English is not our first language, we must be especially mindful of grammar, vocabulary, and syntax to ensure precision and professionalism. Good writing is, at its core, the art of rewriting. The process of drafting, revising, and refining is indispensable. Thorough editing before submission is essential to meet academic standards and effectively convey the intended message

Referencing in Academic Writing

Referencing is a crucial component of academic writing. It ensures the integrity of scholarly work by acknowledging previous research and writings. Proper referencing not only upholds academic honesty but also helps to avoid plagiarism, which is considered intellectual theft. Presenting someone else’s ideas, arguments, or written sections as your own without proper acknowledgment constitutes plagiarism, a serious ethical and academic offense.

There are two primary methods of referencing: direct quotations and footnotes/endnotes. A direct quotation involves using the exact words from a source to substantiate or support an argument. When incorporating direct quotations into your writing, they must be enclosed in quotation marks and followed by a relevant citation. In some cases, direct quotations can also be used to present an opposing argument before refuting it. However, excessive reliance on direct quotations should be avoided, as academic writing values analysis and synthesis over mere reproduction of existing material. In some instances, rather than quoting directly, you may need to paraphrase a long section from another source to maintain conciseness and clarity. Paraphrasing involves restating the ideas of others in your own words while preserving their original meaning. Even when paraphrasing, it is essential to provide a reference to the source to give due credit to the original author.

It is important to note that commonly accepted facts and general truths do not require citations. These include widely known historical dates, scientific laws, and universally acknowledged principles. However, when in doubt, it is always best to provide a citation to maintain academic credibility.

There are several established citation styles used in academic writing, including APA (American Psychological Association), MLA (Modern Language Association), and Chicago style. The choice of citation style depends on the academic discipline and institutional guidelines. Regardless of which citation style you follow, it is important to be consistent and avoid mixing different styles within a single document.

Conclusion

A conclusion serves as the logical summation of a paper, bringing the discussion to a meaningful close. While there is no universal formula, its structure and content depend on the nature of the essay. The primary purpose is to address the central research question or issue posed at the outset, offering a final perspective based on the arguments and evidence presented. Rather than summarizing every point, the conclusion should reinforce the most significant arguments supporting the thesis, ensuring clarity without redundancy. It is not the place to introduce new points, counterarguments, or evidence but should build on the existing discussion to provide a sense of closure. While it does not introduce new arguments, it can briefly suggest directions for future research, especially if there are unresolved questions or broader implications. A well-structured conclusion leaves a lasting impact, reinforcing key insights while maintaining logical coherence.

Bibliography

A bibliography is an essential component of any research paper, providing a comprehensive list of the sources that contributed to the development of the argument. It serves multiple purposes, including giving credit to original authors, ensuring transparency, and allowing readers to verify and further explore the sources used.

If you relied on specific databases to locate sources, these should be mentioned, especially if they played a key role in shaping your research. This helps demonstrate the depth of your literature review and the credibility of your sources. Every source that appears in footnotes or endnotes must be included in the bibliography. This ensures consistency and proper acknowledgment of the works that directly informed your study. Any book, article, or document from which you have taken direct quotes or paraphrased ideas should be listed in the bibliography. This is crucial for maintaining academic integrity and avoiding plagiarism. As with references, there are three main bibliography styles, and the chosen style must align with the one used for footnotes.

Beyond direct citations, it is useful to include major works that influenced your arguments. These may not be explicitly quoted but were significant in shaping your understanding of the subject. While compiling the bibliography, it is important to exercise selectivity and sound judgment. Not every source consulted needs to be included—only those that substantially contributed to the research. The goal is to maintain a focused, relevant, and authoritative list of references rather than an exhaustive or redundant compilation.

(This is based on a discussion the writer had with its Research Staff of the Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies (BCIS) on 13 June 2024.)

Opinion

How Chinese capacity building and USAID slush funds reveal ideological biases of our media

by Shiran Illanperuma

On 9 February, an article titled “Sri Lanka’s Undisclosed Pact with China Worries Media”, which was produced by the Union of Catholic Asian News, was carried in the Sunday Island. The article, which is full of speculation and insinuations, refers to the fact that several MOUs on capacity building are to be signed between Sri Lankan and Chinese state-owned media institutions.

One of the journalists quoted in the article raises concerns over Chinese media being “state-controlled”, while another suggested that partnerships with China would “compromise local media integrity and align it with foreign interests”. The irony is that this news comes in the wake of recent revelations by the Trump administration’s newly minted Department of Government Efficiency, that USAID spent 7.9 million US dollars to train Sri Lankan media.

It reveals a lot about biases in the media profession that partnerships with institutions from China, a rising Global South country that is constantly demonised by the Global North’s media monopolies, is seen as something dangerous and worth campaigning against. Meanwhile, the influx of millions of dollars from a US institution with deep roots in Cold War counterinsurgency and regime change operations is tacitly ignored or underplayed by the so-called defenders of free media.

Double standards

The double standard here is the implicit notion that training, grants, and technical support is ideologically and politically neutral (or positive even!) when the Global North does it. However, if China (or for that matter Russia, Iran or some other designated enemy of the Global North) does it, then of course it is immediately associated with mal-intent. This double standard is nothing but a modern-day manifestation of the trope of oriental despotism.

The easy retort to concerns over media partnerships with China is the simple observation that contemporary China does not seek to export its ideology and institutions. On the other hand, there is ample academic and journalistic evidence on the role of USAID in promoting US interests during the Cold War and beyond. Consider the example of Cuba, where The Guardian reported that the USAID funded a Twitter-like social network to promote content that would encourage the formation of “smart mobs” to “renegotiate the balance of power between state and society”.

There are other examples of USAID’s handiwork in the Global South. One is the case Dan Mitrione, a USAID contractor who worked for the agency’s Office of Public Safety Program in the 1960s. Mitrione oversaw the arming and training of scores of police officers under right-wing governments in Brazil and Uruguay. Mitrione would become notorious for training police officers in the art of torture, with classes on human anatomy, and electroshock and psychological torture.

Decolonising media

The Egyptian Marxist Samir Amin characterised imperialism through five key prongs of domination, one being the control over knowledge. This is why the countries of the Non-Aligned Movement pushed for a New World Information and Communication Order at the 19th Congress of UNESCO in 1970. This process culminated in the 1980 UNESCO report titled ‘Many Vices One World’ which was demonised as an attack on ‘free press’ by the US and UK. The report pointed out the alarming concentration and commercialisation of media, and recommended that countries strengthen their independence and self-reliance. This report so outraged the US that it was one of the reasons for its withdrawal from UNESCO in 1983.

What is striking is how little things have changed in the sphere of media and communications. With the fall of the Soviet Union and China’s shift away from attempting to export revolution, the entire edifice of the Global North’s media and communications monopoly built up during the Cold War continues basically unchallenged today. In addition to traditional media, there is now the dominance of new media companies such as Meta and X (formerly Twitter), which are private monopolies with opaque algorithms, access to sensitive user information from around the world, and close ties to the US government.

In the context of the Global North’s enduring hegemony over media and communication, South-South cooperation in media capacity building is something to be welcomed as a breath of fresh air.

Two traditions

Our understanding of the role of the media in society remains deeply Eurocentric, shaped as it is by the mythology of liberalism where so-called free (i.e. privately owned) media emerged as mouthpiece of the emerging capitalist class in their struggle against feudalism. However, the other side of this coin is the long history of private media in information warfare and suppressing working class and national liberation movements around the world.

The historical role of the media at the weaker links of capitalism is decidedly different. In many of these cases media emerged in the process of decolonisation, and in direct opposition to colonial pedagogy. In China for example, the Xinhua News Agency has its roots as the Red China News Agency in the Ruijin Soviet established by the Communist Party of China in Jiangxi in 1931. The agency was basically forged in fire during the Long March and, following establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, had to function more like an embassy due to the diplomatic isolation imposed by the Global North.

In Sri Lanka too, the true history of the media and its oligarchic owners is yet to be written. While there are certainly shortcomings in the way the nationalised media was managed, there is also an untold story of how important state-owned media was for the proliferation of popular education, health awareness programmes, and uplifting cultural programming for the masses.

In this latter tradition, the state-ownership of media is inseparable from the process of constructing a new society from the detritus of imperialism. How do we even begin to compare this ‘illiberal’ tradition of media that is deeply tied to projects of anti-colonial and socialist state building, to the ‘liberal’ media monopolies of the West which have constantly waged hybrid wars against sovereign states, from Cuba to Venezuela, Iraq to Libya, and yes, even Sri Lanka.

One need only look at recent bias reporting on the US-backed Israeli genocide in Gaza to understand the true face of the Global North’s liberal media monopolies.

(Shiran Illanperuma is a journalist and political economist. He is a researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and a co-editor of Wenhua Zongheng: A Journal of Contemporary Chinese Thought. He is also a co-convenor of the Asia Progress Forum. He has an MSc in Economic Policy from SOAS, University of London.)

(Asia Progress Forum is a collective of like-minded intellectuals, professionals, and activists dedicated to building dialogue that promotes Sri Lanka’s sovereignty, development, and leadership in the Global South. They can be contacted at asiaprogressforum@gmail.com).

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDon’t betray baiyas who voted you into power for lack of better alternative: a helpful warning to NPP – II

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoCommercial High Court orders AASSL to pay Rs 176 mn for unilateral termination of contract

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoSri Lanka face Australia in Masters World Cup semi-final today

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoTwo films and comments

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoUSAID and NGOS under siege

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoDoing it in the Philippines…

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoCourtroom shooting: Police admit serious security lapses

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoFSP lambasts Budget as extension of IMF austerity agenda at the expense of people