Opinion

UK’s deal with Mauritius will be a win for all

Freedom for Chagos islands:

by Peter Harris

Associate Professor of Political Science,

Colorado State University

Britain is close to resolving its territorial dispute with Mauritius over the Chagos Archipelago, located in the central Indian Ocean.

For years, Mauritius has claimed the island group as part of its sovereign territory. It says that Britain unlawfully detached the islands from Mauritius in 1965, three years before Mauritius gained independence. The Mauritian position is backed by international courts and the United Nations, creating enormous pressure for Britain to decolonise.

London, however, has been reluctant to abandon the Chagos Archipelago. This is because the largest island, Diego Garcia, is the site of a strategically important US military base. Britain pledged to make Diego Garcia available to its American ally and has been anxious to avoid a situation where it is prevented from making good on these promises.

The US, for its part, has declined to become publicly involved in the dispute. Its private position is merely that the base on Diego Garcia should not be placed in jeopardy.

In a deal announced in a joint statement, London and Port Louis have agreed that all but one of the Chagos Islands will be returned to Mauritian control as soon as a treaty can be finalised. This comes after nearly two years of intense negotiations. It seems as though settling the dispute was a top priority for Britian’s new Labour government.

Though the deal isn’t done yet, it is expected to go through. Both Britain and Mauritius, along with the White House, have endorsed the agreement, indicating that the toughest negotiations are complete.

Diego Garcia will remain under British administration for at least 99 years – this time with the blessing of Mauritius – enabling Britain to continue furnishing the US with unfettered access to its military base on the island.

In exchange for permission to continue on Diego Garcia, Britain will provide “a package of financial support” to Mauritius. The exact sums of money have not been disclosed but will include an annual payment from London to Port Louis. Both sides will cooperate on environmental conservation, issues relating to maritime security, and the welfare of the indigenous Chagossian people – including the limited resettlement of Chagossians onto the outer Chagos Islands under Mauritian supervision.

I’ve studied the Chagos Islands for 15 years, first as a master’s student and now as a professor. It often looked as though this day would never come.

The deal that’s been announced is a good one – a rare “win-win-win-win” moment in international relations, with all the relevant actors able to claim a meaningful victory: Britain, Mauritius, the US, and the Chagossians.

Win for Britain

Britain went into these negotiations with one goal in mind: to bring itself into alignment with international law.

London suffered humiliating setbacks at the permanent court of arbitration in 2015, concerning the legality of its Chagos marine protected area; at the International Court of Justice in 2019, when the World Court found that Mauritius was sovereign over the archipelago; and at the UN general assembly that same year, when a whopping 116 governments called on Britain to exit the Chagos Islands.

Mauritian sovereignty over the Chagos group had even begun to be inscribed into international case law.

London could probably have defied international opinion if it had wanted to. Nobody would have forced Britain to halt its illegal occupation of the Chagos Archipelago. But such a course would have badly undermined Britain’s global reputation and its ability to criticise others for breaches of international law.

This agreement will give Britain exactly what it wanted: a continued presence on Diego Garcia that conforms with international law.

Win for Mauritius

Mauritius, of course, went into these negotiations intent on securing full decolonisation at long last. Britain and the US now recognise that the Chagos Archipelago belongs to Mauritius.

Mauritius will not have day-to-day control of Diego Garcia, but it will be acknowledged as being sovereign there. The public description of the agreement also doesn’t seem to prohibit Mauritius from exercising its sovereignty over Diego Garcia as it relates to non-military domains.

Win for the US

The US is another clear winner from the deal. In fact, hardly anything will change for America. Washington will continue working closely with London, and will not need to negotiate an agreement with Mauritius on its rights to the base or the status of forces.

Indeed, Pentagon officials should be thrilled that their base on Diego Garcia has been put on firm legal footing. This is something that Britain alone was unable to offer. The bilateral agreement with Mauritius will ensure the security of the base for 99 years – no small feat.

Good for Chagos Islanders

Finally, the deal is good for the Chagos Islanders.

British agents forcibly depopulated the entire Chagos group between 1965 and 1973. The point was to rid the archipelago of its permanent population so that the US base on Diego Garcia would operate far from prying eyes. Britain deported the Chagossians to Mauritius and the Seychelles, which is where most Chagossians and their descendants still live. Some have migrated onwards, including to Britain.

Britain had long opposed the resettlement of the Chagos group by the exiled Chagossians. Mauritius, on the other hand, has indicated its openness to resettlement of the Outer Chagos Islands – so, not Diego Garcia – something that Port Louis is now free to pursue.

Not all islanders have welcomed news of an agreement. The Chagossians are a large and diverse group, with differing views about how their homeland should be governed. Some would have preferred Britain to administer the entire archipelago long into the future, feeling that Mauritius was an unwelcoming host to the exiled Chagossians. But Britain could not hold onto the Chagos Islands forever – at least, not lawfully.

For their part, the largest Chagossian organisations are content with the deal as it has been announced, and will now work with Mauritius on a resettlement plan.

The critics

This is the first instance of decolonisation that London has attempted since returning Hong Kong to China in 1997. Predictably, some in Britain are opposed to the settlement.

Some accuse the Keith Starmer government of “giving up” the Chagos Archipelago. But the islands were never Britain’s to give up – they were always Mauritian sovereign territory, and Britain was an unlawful occupier.

They are also wrong to blame this deal for jeopardising the base on Diego Garcia. The opposite is true: for better or worse, the agreement will resolve any uncertainty about the US base’s future. It will have total legal security.

Finally, critics are grasping at straws when they raise the prospect of Mauritius permitting a Chinese base in the Chagos Archipelago. This is a baseless smear. There is no indication whatsoever that Port Louis has any interest in hosting the Chinese military.

What happens now?

Britain and Mauritius still need to reveal the text of their bilateral treaty. But the deal is highly unlikely to fall through. Both governments, plus the White House, have welcomed the agreement – a sure sign that the hard work of negotiations is over.

All that remains is for the treaty to be ratified – a process that does not require a parliamentary vote in the House of Commons. There is no reason why this cannot be done quickly.

This could be the end of a shameful saga that went on for too long.

(Courtesy of The Conversation.)

Opinion

Drs. Navaratnam’s consultation fee three rupees NOT Rs. 300

Thank you for publishing the article written by Mr Arjuna Hulugalle on my British Empire Medal award. I appreciate the prominence you have given the accolade, but I just wanted to bring to your notice that there was an incorrect reference to charges for patient consultations made by my late parents Dr and Dr Mrs Navaratnam.

I believe it was a type written error and it should read “to every patient the consultation fee was rupees three (NOT Rs 300.00” as stated in the article). My parents did not believe in taking money from their patients as theirs was a service to humanity, but if they did charge patients it was a nominal fee of three rupees or more often than not free of charge.

I hope you will publish this correction on my behalf as my late parents left a tremendous legacy of humanity, kindness and compassion and this does not reflect what they stood for.

Preshanthi Navaratnam

Opinion

81st Birth Anniversary of Dr. (Mrs.) Dulcie de Silva – A tribute

“In the end, it is not the years in your life that count. It is the life in your years.” — a quote from Abraham Lincoln that offers me a unique perspective to reflect on the life and work of Dr Mrs. Dulcie de Silva, whose 81st birthday falls on May 12, 2025. She is fondly addressed as Dulcie. Her life so far has been full of loving relationships, intellectual curiosity, a strong commitment to helping others, and an interesting career in public health with a focus on training primary healthcare workers. These qualities have made her one of Sri Lanka’s most memorable public health figures in recent times.

Dr de Silva’s move to the Institute of Hygiene Kalutara (now the National Institute of Health Sciences – NIHS) in 1976 as a Medical Officer was a defining moment in her life. That was when she truly embraced public health as her lifelong path. Later, she became part of the faculty, training primary healthcare workers, and stood out as one of its pioneers. She had the good fortune to be mentored by the late Dr Godwin Fernando, who took on the role of Chief Medical Officer of Health Kalutara in 1972. She also worked alongside a passionate group of co-workers from various health fields.

In the early 1970s, public health started going through a major transformation, especially in how front-line health workers were trained. This shift really kicked off when Dr Godwin Fernando became Chief Medical Officer of Health.

The transformation was not easy. It was a tough journey driven by Dr Fernando’s strategies, in partnership with his team — with Dr de Silva playing a key role. There was careful planning and structured roll-outs aimed at addressing the country’s health training needs more effectively. Getting approval from the ministry and cabinet was a major hurdle. Dr Fernando and his team had to navigate uncertainty and challenges to get NIHS recognized as a decentralized unit of the Ministry of Health. He had the willpower and skills to face whatever came his way. “Si vis pacem, para bellum” (If you want peace, prepare for war). Dr Fernando had a rare ability to anticipate the future. He was incredibly resilient — able to adapt, recover, and continue. With these strengths, he led an effort to persuade, negotiate, defend, and compromise in the interest of what became a nationally recognized achievement.

This entire journey gave Dr de Silva the experience to equip herself with future-ready skills and long-term success. She believed that “a vision is not enough; it must be combined with venture. It is not enough to stare up the steps; one must also step upstairs.” She believed bringing new life to your life requires focus, dedication, and emotional energy. She was driven by purpose and eventually became the fifth Director of NIHS in 1997 serving until her retirement in 2004.

The golden years of NIHS began with its full autonomy as a decentralized body under the Ministry of Health. This stage involved major developments in human resources, infrastructure and curriculum redesign, to mention but a few.

From the early 1980s, NIHS took new steps in its training programs. A notable example was the community development project in Adikarigoda, a small village near Kalutara, which became a “community school” offering direct training and research opportunities. Dr Halfdan T. Mahler, then Director-General of the World Health Organization, visited both NIHS and this village in the mid-1980s. He was deeply moved by the sense of unity and spirit there. In appreciation, Dr Mahler made a personal donation to restart a preschool project that had stalled for years. Dr Mahler is known for launching the “Health for All by the Year 2000” strategy.

Dr de Silva had a talent for managing problems. She was a moral compass who made steady, thoughtful decisions. Her leadership style was marked by calm strength, confidence, and consistency. She was known for doing ordinary things in extraordinary ways and following the principle: “Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself.”

She was an erudite person with immense potential and experience in teaching and learning — providing a dynamic environment that nurtured intellectual curiosity, critical thinking, and ethical leadership. She believed in lifelong learning. “Ancora imparo” (Still, I am learning) — the Italian quote fits her perfectly.

Dr de Silva’s family and social life were filled with joyful moments and admirable qualities. She was always kind-hearted, cheerful, and modest — someone who lived with grace and grit. I remember the birthday parties of our sons and daughters back in the 1970s when we lived in the NIHS quarters. Today, you have your elder sons, daughter, grandchildren, and Mr. Andrew de Silva — once Secretary of Education close to you in your senior years.

You now lead a virtuous family life deeply rooted in religious and spiritual pursuits. “A virtuous wife was one who led the good life. A good laywoman endowed with religious devotion, moral virtues, and openness as well as wisdom and learning and gifting to charity makes success of her life in this very existence.” (Samyutta Nikaya)

Dr de Silva returned to public life though in a limited way after ten years of retirement, as a co-founder of the NIHS Pensioners’ Association, formed in December 2014. She served as its president for nine consecutive years. The association’s mission is to support the health, social, and spiritual needs of its members, while also showing continued loyalty to NIHS. One of its major achievements was naming the NIHS Auditorium as “Dr Godwin Fernando Memorial Auditorium” — a lasting tribute to a public health pioneer. The association celebrated its 10th anniversary in December 2024, marking a significant milestone.

On aging, Dr de Silva believes that with the right attitude and healthy spirit, aging can bring joy and new rewards. She feels positive aging is about being confident, staying active, and living fully.

She has answered some of life’s deepest questions: How should I live my life? For what should I aim? What values should I live by? These are what some call “Socrates questions.”

Dr de Silva has lived a psychologically rich life — never boring, always full of new experiences. She is a rare blend of qualities in one person. She lived authentically and gracefully and is undoubtedly a true legend of our time. Her contributions to public health are clear and lasting.

As she continues her retirement journey, I wish her good health and much joy in the years ahead.

The wonderful memories we share are priceless.

A.K. Seneviratne

A Former Senior Tutor, Public Health

NIHS Kalutara

Opinion

Ratmalana: An international airport without modern navigational and landing aids

History

In 1934 the State Council of Ceylon decided that an airport with easy access to Colombo was a necessity and declared that Ratmalana was the best site available. Accordingly, an airfield was built, and the first landing took place on 27 November 1935 at what became Ceylon’s first dedicated aircraft landing ground. During World War II the airport expanded, and a ‘hard’ runway was built.

To assist aircraft landing in bad weather and resulting bad visibility, a transmitter was built at Talangama to generate a radio signal beam, called a ‘radio range’, directed along the extended centreline of the Ratmalana runway. If the aircraft was tracking along the correct path, pilots would hear a continuous tone in their headsets. However, if they were left of the desired track, they would hear the letter ‘A’ transmitted in Morse Code (‘dit-dah’); or if right of the beam, the Morse letter ‘N’ (‘dah-dit’). The objective was to hear a continuous signal guiding them toward Ratmalana along the extended centreline of the runway.

Later, a low-frequency Non-Directional Radio Beacon (NDB) transmitter was installed at Attidiya in the vicinity of the airport, and used in conjunction with an Automatic Direction Finder (ADF) onboard the aircraft. A needle on a compass dial in the aircraft pointed to Attidiya, giving directional guidance. Although this system was useful, when most needed, for example during thunderstorm activity, there was static interference and the needles pointed toward the storm instead of at Attidiya. So, a Very High Frequency Omni Directional Radio Range (VOR) was installed for more accuracy and reliability.

After WW2 Ratmalana Airport was served by a few international airlines such as Air Ceylon, Indian Airlines, BOAC (British Overseas Airways Corporation) and TWA (Trans World Airlines). But in 1968 the airport lost its ‘international’ status when Bandaranaike International Airport opened and all international operations moved to Katunayake. Subsequently, the equipment at Ratmalana was allowed to deteriorate; radio navigational let-down aids were no longer operative, and there was no proper control tower. The civil training aircraft of the government’s flying school had neither radios nor radio aids to navigation.

Even the runway lights didn’t work, and domestic flights had to depend on kerosene lamps to demarcate the runway limits. Flares from oil lamps were the guiding light for all traffic landing at Ratmalana Airport. One redeeming grace, in the night, in those days, was that the Sapugaskanda Oil Refinery was in full production and a giant flare of the burning gasses was the guiding light to all domestic traffic landing at the Ratmalana Airport. The Pilots spotted the flare from far away and flew over the Refinery and then turned on the runway heading and could see the runway edge kerosene flares, flickering dimly in a dark patch that was the Ratmalana airport!

Post-1977 and the Dharmista government, another problem was created for Ratmalana operations. Sri Lanka’s capital was moved to Sri Jayewardenepura, Kotte, and a new Parliament complex built there. Unfortunately, the parliamentary precinct was only 3.6 nautical miles (NM) from the end of the Ratmalana runway ‘as the crow flies’, and less than 1 NM from the Talangama transmitters. In most countries overflying the Parliament is prohibited, and Sri Lanka decreed it wouldn’t be an exception to the rule.

This decision was detrimental to freedom of aircraft movements to the Ratmalana runway, preventing longer, safer, conventional landing approaches. At the time Air Ceylon, the Sri Lanka Air Force (SLAF) and other domestic flights were still using Ratmalana airport. Many professionals observed that it was akin to someone building a house near an existing railway line and then complaining that it was too noisy and requiring the railway to divert. This is not unlike the widely-known ‘NIMBY’ phenomenon: Not In My Back Yard.

Consequently, aviators had to accept the non-availability of precision navigational aids at Ratmalana as the Talangama transmitters lost their significance. The Urban Development Authority (UDA) eventually took vacant possession of the Talangama precinct, and the Sri Lanka Army’s Gemunu Watch infantry regiment established a camp there.

During December’s clear nights and cooler mornings, temperature inversions combined with the northeasterly winds blowing smoke from the Sapugaskanda Oil Refinery seriously compromise visibility on the final approach to Ratmalana airport. (See image 1)

On the morning of 14 December 2014, a SLAF Antonov An-32 transport aircraft on a ferry flight from Katunayake attempted to approach for landing at Ratmalana airport and crashed. This prompted the then Air Force Commander to write to the then Director General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) to reinstall navigational facilities (see letter below). Now, after almost 11 years, Airport and Aviation Sri Lanka (AASL) is slowly realising that not only the ‘seen’ but also ‘unseen’ facilities at Ratmalana should be brought up to international standard in the name of air safety. Wide publicity was given to the fact that the government’s intention was to make Ratmalana an international business aircraft hub by way of regaining its past importance. In fact, it is now known as the Colombo International Airport Ratmalana (CIAR). (See image 2)

Image 2

Meanwhile, another security-sensitive building has been erected and commissioned on vacant land at the former site of the Talangama transmitters, barely 1 NM from the Parliament and 4.4 NM from the Ratmalana runway end. That is the Akuregoda Military Head Quarters, which has created an effective manmade barrier to limit operation of legitimate air traffic to Ratmalana, consequently imposing more restrictions on inbound operations. Furthermore, it appears that there was no ‘master plan’ for Ratmalana International Airport, in a case of the left hand not knowing what the right hand was doing. (See image 3)

Air safety dictates that jet aircraft should have at least an 8 mile straight-in (no turns) final approach. Now it is not possible to do that with the unplanned presence of sensitive buildings on the final approach to Ratmalana. Ideally, as in other countries, all three parties – the local municipality town planner; Civil Aviation Authority/ Airport and Aviation Ltd (CAASL/ AASL); and building developer – must make these long-term decisions. In Australia, for instance, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority and relevant airports authorities have control of manmade obstacles for a radius of 25 miles. In Sri Lanka, unplanned buildings, called ‘man-made relief’ as against ‘geographic relief’ (terrain), have compromised feasibility of the intended city airport.

Another example is the General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University (KDU), the tallest building in the vicinity of Ratmalana Airport that should never have been allowed to be built that high. This is symptomatic of a malady the entire country is suffering from: people in the know are afraid to speak up. Subsequently, no one is held accountable for these poor, uncoordinated decisions without true professionals being consulted, resulting in tunnel vision. As a pithy Sinhala saying goes, “ledaa malath, bada suddai” (‘although the patient died, the bowels were clean’).

Accommodating ‘business jets’ (‘bizjets’, or executive jets) at Ratmalana Airport will be a good source of revenue, and a step in the right direction. Putting aside criticism of how Ratmalana Airport was allowed to run down, I write to offer a practical solution to mitigate the adverse effects of unplanned buildings. While the Akuregoda military base is working around the clock, the overflying prohibition may be justified. But Parliament sits only on certain days and for limited hours.

Therefore, the authorities should provisionally allow air traffic, inbound to Ratmalana, to overfly the Parliament complex on days and times when there are no sittings. A Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) to that effect could be issued as and when necessary.

The over-flight of the Parliament would become ‘Restricted Airspace’, not ‘Prohibited Airspace’. With airspace thus shared for the benefit of all users, longer and therefore safer approaches could be designed to facilitate those small but fast bizjets from overseas operating in and out of Ratmalana Airport.

The differences in airspace regulation and restrictions are as published by the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO).

Restricted Area/Airspace is defined as an area of airspace where flight is permitted only under certain conditions. These conditions may include obtaining permission from the airspace’s controlling authority, flying at a certain altitude, or following a specific route. Restricted airspace is typically used for military training, testing, or other activities that require special precautions.

A restricted area is an airspace of defined dimensions above the land areas or territorial waters of a state, within which the flight of aircraft is restricted in accordance with specific conditions. (ICAO Annex 2: Rules of the Air)

Prohibited Area/Airspace is an area of airspace where flight is completely prohibited. This type of airspace is typically established for national security reasons, such as protecting sensitive government facilities or military bases. In some cases, prohibited airspace may also be established for safety reasons, such as around airports or other areas with high levels of air traffic.

A prohibited area is an airspace of defined dimensions, above the land area or territorial waters of a state, within which the flight of aircraft is prohibited. (ICAO Annex 2: Rules of the Air)

Furthermore, Ratmalana Airport lacks a proper Control Tower with a 360-degree range of visibility of the airport area. It is time to ‘think out of the box’. A new Control Tower could be sited in the highest point in the vicinity. Perhaps at the KDU building to mitigate the situation. At Wellington Airport, serving the capital of New Zealand, the control tower is on top of a shopping mall! (See image 4)

Image 4: Wellington Airport, New Zealand, control tower above a shopping Mall

A, research shows that light training aircraft and other small aircraft of the size and mass of business jets cannot create catastrophic destruction to strong buildings such as our Parliament or the Akuregoda military base, similar to what happened on September 11, 2001 in the USA with large passenger jets. (See image 5)

The Current Status at Colombo International Airport Ratmalana.

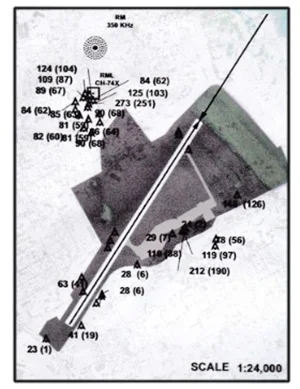

A map of Ratmalana Airport with heights of significant obstacles. The height above Mean Sea Level (MSL) is the first figure. The height above the airport reference point is within brackets. Note: The KDU is 212 ft. above MSL, standing at a height of 190ft. (See image 5)

Although publicised as an ‘international airport’, Ratmalana does not even have a ground-based precision electronic navigation or landing aid such as a Very high Frequency (VHF) Omnidirectional Radio range (VOR) or an Instrument Landing System (ILS). An excuse for that lack is that unplanned buildings such as the Sri Lanka Air Force Museum are obstructing navigational signals. Even if ground-based radio navigational aids are not available, modern satellite-based navigational aids such as a Global Positioning System (GPS) could be used.

India has already launched satellites into space and positioned a Geo-Augmented Navigation (‘GAGAN’) satellite for GPS navigation over this part of the world. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka has failed to request India to share use of the system. In the above map ‘RM’ (top left) is the NDB situated at Attidiya, and is not aligned with the extended centreline of the existing runway.

The Ratmalana terminal building was built in the likeness of many ‘colonial’ airports in the 1950s. It was often used for international movie backdrops. Unfortunately, the airport administration demolished parts of this historic terminal to accommodate an ugly temporary structure.

There is still no air traffic control tower conforming to international standards with a 360-degree view. From the building that is being used, air traffic control officers cannot see the south side of the airport and the runway at the Galle Road end.

The author (5ft 6in tall) beside the controversial hazardous wall at Colombo International Airport, Ratmalana

Speaking of the Galle Road end, there is still that concrete (or cement brick) wall which is considered a hazard by all experienced pilots, yet the authorities continue to ignore demands for its removal. To clarify, a hazard, according to EASA (European Union Aviation Safety Agency), is “a condition or an object with the potential to cause or contribute to an aircraft incident or accident.”

The EASA goes on to state that one way of identifying a ‘hazard’ is accepting the opinion of experts with professional knowledge. Accordingly, 22 very experienced pilots with experience totalling 330,500 hours petitioned the then Director of Civil Aviation to remove the concrete wall at Colombo International Airport Ratmalana and replace it with a frangible fence. The letter is produced below.

2nd November ‘18

The Director General,

Civil Aviation Authority,

Minuwangoda Road,

Katunayake.

Dear Sir,

The Concrete Wall at the Galle Road End at the Ratmalana Airport

Attached herewith is a petition signed by 22 very experienced pilots, who feel strongly about the presence of the concrete wall at the Galle Road end of the Ratmalana Airport.

The petitioners have a total of 330,500 hours and consist of a cross-section of some of the most experienced pilots in the land.

It is hoped that you will heed their call and at least get the process going.

Thanking you in anticipation.

Yours truly,

Capt. G A Fernando

The author (5ft 6in tall) beside the controversial hazardous wall at Colombo International Airport, Ratmalana

But the airport authorities couldn’t care less. I believe that the main reason for this sad situation is that none of the present airport administrators are or have been aviators.

“If you think that Air Safety is expensive, try an accident” Jerome Lederer, President, Flight Safety Foundation, USA

gafplane@sltnet.lk

The Writer is Immediate past President, Aircraft Owners and Operators Association (AOAOA)

RCyAF/ SLAF, Air Ceylon, Air Lanka, Singapore Airlines (SIA), SriLankan Airlines

President, Colombo Flying Club.

President, UL Club (an Association of Former Air Lanka and SriLankan Airlines Employees)

Life Member of the Organisations of Professional Associations (OPA)

by Capt G A Fernando

MBA (UK)

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoAitken Spence Travels continues its leadership as the only Travelife-Certified DMC in Sri Lanka

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoNPP win Maharagama Urban Council

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoLinearSix and InsureMO® expand partnership

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoSAITM Graduates Overcome Adversity, Excel Despite Challenges

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoJohn Keells Properties and MullenLowe unveil “Minutes Away”

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoASBC Asian U22 and Youth Boxing Championships from Monday

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoDestined to be pope:Brother says Leo XIV always wanted to be a priest

-

Foreign News3 days ago

Foreign News3 days agoMexico sues Google over ‘Gulf of America’ name change