Opinion

Tools of liberation: Anagarika Dharmapala’s industrial vision

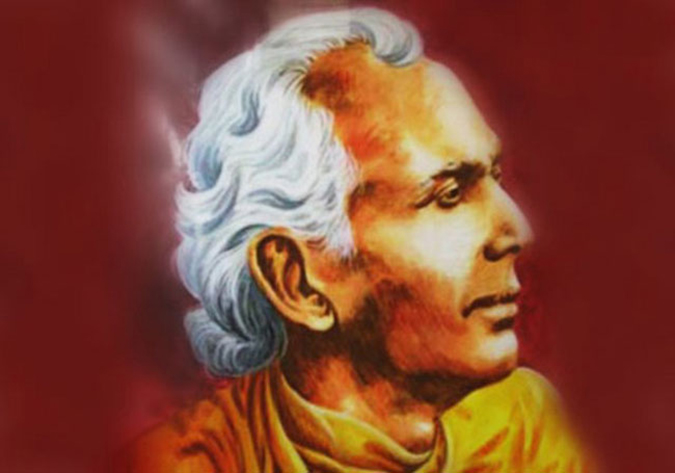

Of the many figures who shaped modern Sri Lanka, Anagarika Dharmapala (1864-1933) stands apart as a colossus of cultural and religious revival. He is most famously remembered for his pivotal role as a spiritual reformer and nationalist, in resuscitating Theravada Buddhism and Sinhalese nationalist sentiment. However, his contributions to industrial training and economic upliftment are equally profound, although often overshadowed. Less explored than his revivalism, a profoundly significant dimension of his work lies in his vision for industrial and economic self-sufficiency, which encompassed the material and vocational empowerment of the people, particularly in response to colonial economic structures that left local communities impoverished and dependent.

“We allow our cow to die”

Dharmapala believed that true independence was impossible without economic independence. His industrial philosophy was born from a stark diagnosis of the condition of his people under British rule. He observed a native population that had been systematically stripped of its confidence, skills, and economic agency. The colonial economy was designed to keep Ceylon as a supplier of raw materials (tea, rubber, and coconut) and a consumer of manufactured goods imported from Britain and food from elsewhere. “We allow our cow to die of starvation in our own field,” he said, “while we feed the cow in distant Switzerland or Denmark.”

This system, Dharmapala argued, created a state of parasitic dependency, enfeebling the people and eroding their traditional crafts and self-reliance. His famous exhortations were aimed at this psychological and economic malaise: “We are a lazy people; we are an ignorant people; we are a superstitious people.” This was not an insult but a call to awaken from this induced stupor and reclaim their inherent potential.

Dharmapala’s fervent advocacy for industrial development was deeply rooted in his own familial background, having as successful medium-scale entrepreneurs both his father, H. Don Carolis, and his maternal grandfather, LAP Dharmagunawardena. His father, in particular, founded a highly regarded furniture-manufacturing business that pioneered modern techniques, achieving such renown that it exported furniture across the globe. In 1904 Don Carolis established the modern mechanised Ceylon Steam Furniture Works in Slave Island, which incorporated the first wood-curing kiln in Sri Lanka.

Japanese manufacturing

This direct exposure to successful native enterprise profoundly shaped Dharmapala’s understanding of economic self-sufficiency, focusing his attention on the critical need for industrial growth as a foundation for national strength. This belief was powerfully reinforced during his first visit to Japan, where he witnessed first-hand the rapid modernisation of the first Asian country to industrialise, cementing his conviction that Ceylon’s path to independence and dignity depended on embracing a similar industrial and technical revolution.

Recognising the sophistication of Japanese manufacturing, Dharmapala sent his brother Edmund there to study its industrial and commercial methods. His family used his connections to the match industry in that country to develop their own match industry in Sri Lanka. In 1917 they launched the Ceylon Match Company, manufacturing the famous “Two Elephants” brand matches. Dharmapala’s nephew Kumaradas Moonesinghe served as its first managing director.

Dharmapala’s filled his editorials in The Sinhala Bauddhaya with exhortations to “wear local clothes” and to reject foreign luxuries, which he deemed responsible for the economic and spiritual impoverishment of the people. He associated foreign goods with moral decadence and weakness, while local production was tied to purity, strength, and national pride. Thus, his ideology had a comprehensive socio-economic outlook designed to use consumption as a tool for national liberation, pre-dating and paralleling the broader Swadeshi movement in India.

Rajagiriya

Dharmapala believed that economic independence required a population skilled in modern industries and crafts. Accordingly, he sent his own nephews overseas to study technical subjects. For instance, Rajasinghe (“Raja”) Hewavitarne went to Coventry Technical College to study engineering, gaining industrial training at the Humber car factory.

Shortly before his demise, at Dharmapala’s instigation, Don Carolis set up the Industrial Scholarship Trust, a programme to send young men to Japan to be trained in that country’s industrial best practices. The first, U.B. Dolapihilla, studied at the Tokyo Higher Technical School (now the Tokyo Institute of Technology) and returned in 1913, to preside over the Hewavitarne Weaving School in Rajagiriya.

Dharmapala bought Ananda Coomaraswamy’s Welikada mansion “Rajagiriya” (now known as “Obeysekera Walauwa”), which gave its name to the entire suburb. On its grounds, in 1912, his brothers Edmund and Simon established the Weaving School, one of the most tangible expressions of his industrial vision. The writer’s great-grandfather, Jacob Moonesinghe, served on the board.

This was not the first Hewavitarne industrial school. The family had already established a free Industrial School next to the works at Slave Island, where boys received training in carpentry. It is now no longer extant. The buildings which housed the, now largely forgotten, Hewavitarne Weaving School in Rajagiriya serve today as warehouse space for the Department of Textile Industries. However, they also remind us of Dharmapala’s vision.

Tuskegee

Dharmapala’s global outlook and strategic thinking are revealed by his admiration for the Tuskegee Institute, founded by Booker T. Washington in Alabama, in the United States. Renowned for its emphasis on industrial education for African Americans, Tuskegee combined academic instruction with hands-on training in agriculture, mechanics, and domestic sciences. Washington’s philosophy of “dignity in labour” and “self-help” resonated deeply with Dharmapala’s own ideals.

The institute demonstrated how marginalised communities could resist systemic oppression through education and enterprise. Dharmapala saw in it a model for Sri Lanka, a way to empowerment without waiting for political concessions from the British. He believed that, like African Americans in the post-slavery South, the natives needed institutions that could instil discipline, skill, and pride in productive labour.

Inspired in part by the example of the Tuskegee Institute, Dharmapala sought to integrate a comprehensive programme of industrial and vocational education into the broader struggle for national regeneration.

He championed tirelessly the idea that the youth of Sri Lanka should be trained in the very professions that powered a modern society, as engineers, carpenters, metalworkers, weavers, and printers. This was a radical shift away from the colonial education system, which produced primarily clerks and minor functionaries to serve the administrative machinery of the empire. He extended this thinking to India, establishing an Industrial School in Sarnath, Benares, with funding from the Hawiian Buddhist Mary Elizabeth Mikahala Robinson Foster.

Industry as Resistance

Dharmapala’s industrial efforts concerned resistance to colonial subjugation as well as economic development. By promoting local manufacture and vocational education, he challenged the colonial economy’s dependence on imported goods and foreign expertise. He recognised the hollowness of political or cultural freedom without economic agency. By planting the seeds of technical education and championing local industry, he sought to build a nation with not only spiritual and cultural confidence but also economically self-reliant and capable of standing on its own feet in the modern world.

This was not about recreating a mythical past but about equipping the people to compete and excel in the contemporary industrial world. His vision provided the foundational ethos for the later movements that would struggle for independence, making him a true prophet of both spiritual and industrial awakening.

The most concrete manifestation of this philosophy would be the establishment of technical schools and training centres, within a national policy prioritising skill development. While his grand vision for a vast network of such institutions only became a partial reality in his lifetime, he laid the critical groundwork for later developments in vocational education in Sri Lanka. When my late father, Anil Moonesinghe converted the Ceylon-German Training School into the Ceylon-German Technical Training Institute, he consciously followed in the footsteps of his forebear.

Dharmapala wanted Sri Lankan industries to be so advanced that they would eventually produce goods for export, reversing the colonial flow of trade. In an era of global economic uncertainty and postcolonial rebuilding, Dharmapala’s model remains strikingly relevant. His synthesis of spiritual values with industrial pragmatism offers a blueprint for holistic development, empowering society while strengthening national resilience.

The writer is a former Chair of the Ceylon-German Technical Training Institute, Vinod Moonesinghe is a descendant of Anagarika Dharmapala’s sister Engeltina Hewavitarne and her husband Jacob Moonesinghe. He is a convenor of the Asia Progress Forum.

By Vinod Moonesinghe

Opinion

A national post-cyclone reflection period?

A call to transform schools from shelters of safety into sanctuaries of solidarity

Sri Lanka has faced one of the most devastating natural disasters in its post-independence history. Cyclone Ditwah, with its torrential rains, landslides, flash floods, and widespread displacement, has left an imprint on the nation that will be remembered for decades. While rescue teams continue to work tirelessly and communities rush to rebuild shattered homes and infrastructure, the nation’s disaster assessment is evolving by the day. Funds from government channels, private donations, and the Sri Lankan diaspora are being mobilised and monitored with care. Humanitarian assistance—from the tri-forces and police to religious institutions and village communities—has surged with extraordinary compassion, but as in every disaster, the challenge ahead is not only about restoring physical structures; it is also about restoring the social and emotional fabric of our people for a sustainable future.

Schools on the Frontline of Recovery

The Ministry of Education is now faced with a difficult but essential question: When and how should schools reopen? The complexity of the problem is daunting. Hundreds of schools are either partially submerged, structurally damaged, or being used as temporary shelters, bridges and access roads have collapsed, and teachers and students in highly affected districts have lost family members, homes, and belongings. And yet, not all regions have suffered to the same degree. Some schools remain fully functional, while others will require weeks of rehabilitation.

The country has navigated a similar challenge before. In 2005, following the tsunami that hit mainly the coastal areas of the island, the education system faced a monumental recovery phase, requiring temporary learning spaces, psychosocial support units, and curriculum adjustments. During the COVID-19 pandemic, schools reopened in staggered phases with special protocols. International schools and private educational institutions, with greater autonomy, are likely to restart their academic calendar earlier. Regardless of whether a school belongs to the national, provincial, Pirivena, or international sector, however, education must restart sooner rather than later. The reopening of schools is not merely an administrative decision; it is a symbolic and structural step toward national healing and a restorative future for the country.

Disasters Do Not Discriminate — Neither Should Education

Just like the tsunami of 2004, the major floods of 2016, the landslides of Aranayake (2016), Meeriyabedda (2014), and Badulla (2022), and the Covid-19 pandemic (2021), the cyclone Ditwah has once again exposed the fragile but deeply profound truth that natural phenomena do not recognize distinctions created by humans. Floodwaters do not differentiate between provinces, school systems, or social classes; landslides do not check national exam results before destroying a home; and suffering does not pause to ask whether a child is from a rural Mahaweli village or an elite urban suburb.

In this context, educational institutions have a responsibility that goes far beyond exams and syllabi. This aligns profoundly with an often-cited principle of Jesuit education articulated in 2000 by Fr. Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, S.J., the former Superior General of the Society of Jesus:

Tomorrow’s whole person cannot be whole without an educated awareness of society and culture, with which to contribute socially, generously, in the real world. Tomorrow’s “whole person” must have, in brief, a well-educated solidarity… learned through “contact” rather than “concepts.” When the heart is touched by direct experience, the mind may be challenged to change. Personal involvement with innocent suffering, with the injustice others suffer, is the catalyst for solidarity which then gives rise to intellectual inquiry and moral reflection.”

In this sense, schools must guide children to process what they have witnessed—directly or indirectly—and transform these experiences into moral resilience, empathy, environmental consciousness, and collective responsibility. In doing so, one should bear in mind that every child in Sri Lanka has experienced Cyclone Ditwah in some way:

Children Who Faced the Disaster Directly:

Some children lived through the cyclone in the most harrowing ways—watching floodwaters creep into their homes, escaping rising torrents, or fleeing as landslides tore through familiar ground. Their memories are filled with the sound of rushing water, collapsing earth, and the frantic efforts of parents and neighbours, losing their family members, and trying to keep everyone safe.

Children Who Supported Frontline Families:

Others experienced the crisis through the lens of responsibility. They watched fathers, mothers, siblings, or relatives join rescue teams, distribute supplies, or help evacuate neighbours. These children carried a different kind of fear—waiting in silence, praying that their loved ones would return safely from dangerous missions.

Children Who Witnessed the Disaster Through Media:

Many encountered the cyclone from within their homes or shelters, glued to phones, televisions, and social media feeds. They saw images of villages underwater, families stranded on rooftops, frantic cries for help, boats battling fierce currents, and choppers airlifting stranded people. Even from a distance, these scenes left deep emotional imprints.

Children Who Internalised the Atmosphere of Fear:

Some were not exposed directly to images or destruction, but absorbed the tension in their households—whispered conversations, worried faces, disrupted routines, and sleepless nights. Their experience was shaped by the emotional climate around them: the uncertainty, the stress, and the unspoken fear shared by the adults they depend on.

Children Who Got Involved in Relief Efforts:

Across Sri Lanka, countless children became active participants in relief efforts—some spontaneously, others through families, schools, churches, temples, mosques, and youth groups. Individually, they helped neighbors carry belongings, comfort younger children who were frightened, fetch water and dry rations, and assist the elderly in evacuation centers. Within families, many helped prepare meals for displaced people, sorted clothing donations, packed dry-food parcels, and joined parents in visiting affected households. Through organizations, such as temples, churches, mosques, charity foundations, school associations, clubs, scout groups, Girl Guides, Sunday school units, youth groups, and student unions, children coordinated collection drives, raised funds, gathered books and uniforms for those who are affected, and volunteered at distribution points. These acts, small and large, are beacons of the nation’s hope, revealing that even a crisis as destructive as Cyclone Ditwah, Sri Lankan children were not only making meaning of suffering, but also cultivating compassion, solidarity, and shared responsibility.

In one way or another, Sri Lanka’s children have been touched by the experience. Their hearts are stirred. Their minds are open. While not all trauma comes from direct contact, indirect exposure can be equally jarring, especially for younger children; their psychological, emotional, and social well-being must be handled with sensitivity and foresight. This moment, therefore, is an educational opportunity of rare depth—if we have the courage and creativity to embrace it.

A National Post-Cyclone Reflection Period (NPCRP)?

Once schools reopen, no child should simply return to the classroom as if nothing happened. A top-down insistence on “catching up” academically without addressing emotional wounds will only store up psychological problems for the future. Instead, schools should designate an initial period for reflection, storytelling, sharing, healing, and meaning-making. Hence, a mandatory National Post-Cyclone Reflection Period (NPCRP) is not merely a “feel-good” recommendation. It draws from post-tsunami educational reforms both in Sri Lanka (2004) and in Japan (2011), WHO frameworks for psychosocial healing in schools, UNICEF guidelines on post-disaster learning environments, and our own cultural traditions of collective mourning and remembrance in Sri Lanka. In Sri Lanka, villages often come together after a death for almsgivings, month-mind ceremonies, etc. Our religions—Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism—each emphasize compassion, reflective mourning, and community healing. Why should schools not embody these cultural strengths after a catastrophe that has impacted an entire nation?

(To be concluded)

(Dr. Rashmi M. Fernando, S.J., is a Jesuit priest, educator, and special assistant to the provost at Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, California, USA.).

by Dr. Rashmi M. Fernando, S.J.

Opinion

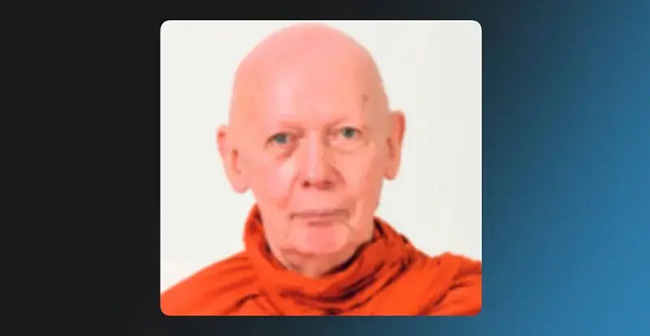

Venerable Mettavihari Denmarke passes away

Danish Monk Who Revolutionised Digital Buddhism and World’s Buddhist Media

The Buddhist community in Sri Lanka and around the world is mourning the passing of Venerable Mettavihari Denmarke, the Danish-born monk whose pioneering work transformed the modern dissemination of Theravada Buddhism. He passed away peacefully in Denmark recently, after battling with cancer.

Born Jacub Jacobson, a Christian and a successful businessman in Denmark for more than 18 years, he was drawn to the timeless truth of the Four Noble Truths and the serenity of the Noble Eightfold Path. This spiritual awakening led him to the Buddhist Order, where he was ordained under Ven. Agga Maha Panditha Madihe Pannaseeha Maha Nayake Thera, receiving the name Bhikkhu Mettavihari.

A Life Rooted in Sri Lanka

Venerable Mettavihari first arrived in Sri Lanka in 1969 and immediately felt a deep connection to the island and its people. Inspired by the purity of the Dhamma, he made Sri Lanka his permanent home. In 1988, both he and his wife entered the Buddhist Order – he as a monk and she as a nun dedicating themselves wholeheartedly to the Sasana.

Remembered for Compassion and Humility

I was fortunate to associate with him for over 10 years on several projects. His kindness towards all living beings and his sincere practice of the Dhamma were exemplary even for monks.

I recall one occasion when he attended a full-day workshop on neuroscience and Buddhism simply to encourage me. He stayed throughout, offering blessings and support. That day the devotees responsible for bringing Dana were late, yet he asked only for a piece of bread, as he was committed to maintaining the Vinaya discipline of eating before noon.

He was often seen walking barefoot on alms rounds gentle, humble, and entirely detached from worldly comforts.

His studio was always open to me, welcoming any noble work and encouraging efforts to help people lead meaningful, wholesome lives.

He was a strict Vinaya practitioner, a monk of exceptional discipline, simplicity, integrity, compassion, loving-kindness, and empathy that were beyond imagination.

A Pioneer of Digital Buddhism

Before his ordination, Venerable Mettavihari worked in the IT field in Denmark. He used this expertise to usher Buddhism into the digital age.

Through metta.lk, he created one of the world’s earliest online Buddhist databases, digitising the Tripitaka and making it available in three languages. He also provided email services to temples and ensured that Dhammapada verses accompanied each message quietly spreading the Dhamma across the globe.

Founder of Dharmavahini – Sri Lanka’s First Buddhist TV Channel

He founded Dharmavahini, Sri Lanka’s first Buddhist television channel, run by a small team of volunteers with minimal resources. More than a broadcaster, Dharmavahini was his effort to restore forgotten values in Sri Lankan society.

Today, it remains a landmark contribution to Buddhist media.

Educational Reformer – Founder of Learn TV

After witnessing the educational challenges faced by rural children following the 2004 tsunami, Venerable Mettavihari launched Learn TV, a 24-hour educational channel developed with the Ministry of Education.

This enabled thousands of students, especially those without tuition or teachers, to receive continuous, curriculum-based lessons from home.

A Monk Who Became Sri Lankan at Heart

Fluent in Sinhala and immersed in Sri Lankan culture, he often referred to himself simply as “a Sri Lankan.” During a conversation with friends, he humorously admitted that speaking Danish had become difficult, “because I am now a Sri Lankan.”

Noble Life and a Lasting Legacy

Most Venerable Mettavihari (aged 80)

With boundless compassion and humility, he uplifted countless lives through education, media, technology, and the Dhamma.

His legacy includes:

- Digitising the Tripitaka and pioneering online Buddhist resources

- Establishing Dharmavahini, Sri Lanka’s first Buddhist TV channel

- Launching Learn TV to uplift rural education

- Advancing global Buddhist communication through IT

- Strengthening moral values in Sri Lankan society

He was also an ardent supporter of the Light of Asia Foundation since its inception. He supported and guided the production of the Siddhartha movie, the establishment of the Sakya Kingdom, the International Film Festival, and, just a few months ago, he participated in the first production of a short video series on the Sutta which is currently under production and expected to be launched soon.

His life stands as a rare example of innovation, devotion, and deep spiritual conviction.

Venerable Mettavihari passed away mindfully at his home in Denmark.

His passing is a profound loss not only for Sri Lanka, but for the world.

May this noble monk attain the supreme bliss of Nibbana

Lalith de Silva

Former President, Vidyalankara Maha Pirivena Trustee, Light of Asia Foundation

Opinion

Maha Jana Handa at Nugegoda, cyclone destruction, and contenders positioning for power in post-NPP Sri Lanka – I

The Joint Opposition rally dubbed the ‘Maha Jana Handa’ (Vox Populi/ Voice of the People) held at the Ananda Samarakoon Open Air Theatre, Nugegoda on 21 November, 2025 has suddenly acquired a growing potential to be remembered as a significant turning point in post-civil conflict Sri Lankan politics, in the wake of the meteorological catastrophe caused by the calamitous Ditwah cyclonic storm that devastated the whole country from north to south and east to west on an unprecedented scale. But the strength of this prospect depends on the collective coordinated success of the future public awareness raising rallies, promised by the participating opposition parties, against the incumbent JVP-led NPP government. They are set to expose what they perceive as the government’s utterly inexperienced and unexpectedly authoritarian stand on certain vitally important issues including the country’s national security and independence, political and economic stability, and the Lankan state’s unitary status. The government is also alleged to be moving towards establishing a form of old-fashioned single party Marxist dictatorship in place of the firmly established system of governance based on parliamentary democracy, which was almost toppled by the adventitious Aragalaya protest of 2022 but saved by the timely intervention of some patriotic elements.

The minefield of policy making that the government must negotiate is strewn with issues including, among others: the seven or so recent agreements or MOUs (?) secretly signed with India; the unresolved controversy over the allegedly illegal clearance of some 323 containers (with unknown goods) without mandatory Customs inspection, from the Colombo Port; the Prime Minister’s arbitrary, apparently ill-considered and hasty education reforms without proper parliamentary discussion; the proposed culturally sensitive lgbtqia+ legislation non-issue (it is a non-issue for Sri Lanka, given its dominant culture); the so-called IMF debt trap; dealing with the unfair, virtually unilateral UNHRC resolutions against Sri Lanka; the inexplicably submissive surrender of the control of the profit-making Colombo Dockyard PLC to India; some government personal assets declarations that have raised many eyebrows, and the government’s handling of anti-narcotic and anti-corruption operations. The opposition politicians relentlessly criticise the ruling JVP/NPP’s failure to come out clean on these matters. But they themselves are not likely to be on an easy wicket if challenged to reveal their own positions regarding the above-mentioned issues.

In addition to those problems, the much more formidable challenge of unsolicited foreign-power interference in Sri Lanka’s internal affairs, in the guise of friendly intervention, remains an unavoidable circumstance that we are required to survive in the geostrategically sensitive region where Sri Lanka is located. Having been active right from the departure of the British colonialists in 1948, the foreign interference menace intensified after the successful ending of armed separatist terrorism in 2009. Such external interferences are locally assisted by latent domestic communal disharmony as well as real political factionalism, both of which are normal in any democratic country.

The war-winning President Mahinda Rajapaksa, as the leader of the SLFP-led United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA), was made to suffer a largely unexpected electoral defeat in 2015 through a foreign-engineered regime change operation that tacitly favoured his key rival, UNP leader Ranil Wickremesinghe. Mahinda was betrayed by his most trusted lieutenant Maithripala Sirisena.

The SLFP, a more middle of the way socialist-leaning rival political party, was formed in September 1951—five years after the birth of the UNP—and was elected to power in 1956, ending a near decade under the rather West-friendly latter party. It was deemed to be a ‘revolution’ that started an era of ‘transition’ (from elitist to common citizen rule). From nominal independence in 1948, governing power has to date alternated between these two parties or alliances led by them, except for the last electoral year, 2024. Though incumbent Executive President Anura Kumara Dissanayake may be said to have made history in this sense, the fact remains that he was barely able to scrape just 43% of the popular vote as the head of a newly formed, JVP-led NPP. Dissanayake was sworn in as President in September 2024. But his less than convincing electoral approval triggered a massive victory for the NPP at the parliamentary election that followed in November, giving him a parliament with 159 members, which is unprecedented in Sri Lanka’s electoral history.

In my opinion, there are two main reasons for this outcome. One is that the average Sri Lankan voters trust democracy. Since the president elect is accepted as having won the favour of the majority of the pan-Sri Lankan electorate, the general public choose to forget about their personal party affiliations and tend to vote for the parliamentary candidates from the party of the elected president. This is particularly true of the majority Sinhalese Buddhist community represented by the two mainstream, non-communal national parties, the UNP and the SLFP. The brittle foundation of that victory is not likely to sustain a strong enough administration that is capable of introducing the nebulous ‘system change’ that they have promised in their manifesto, while it is becoming clear that the general performance of the government seems to be falling far short of the real public expectations, which are not identical with the unconscionable demands made by the few separatist elements among the peaceful Tamil diaspora in the West, to whom the JVP/NPP alliance seems to owe its significantly qualified electoral success in 2024.

The Maha Jana Handa reminded me of the long Janabalaya Protest March from Kandy to Colombo where it ended in a mass rally on September 5, 2018. That hugely successful event was organised by the youth wing of the SLPP led by Namal Rajapaksa, who was an Opposition MP during the Yahapalanaya. He has played the same role just as efficiently on the most recent occasion, too. At the end of his address during the Maha Jana Handa, he declared his determination to bring down the malfunctioning JVP/NPP government at the earliest instance possible. Probably, he missed Ranil’s protege Harin Fernando’s speech that came earlier. This was because Namal Rajapaksa joined the rally midway. Harin had brought a message from his mentor Ranil to be read out to the rally audience. But he said he didn’t want to do so after all, saying that it was not suitable for that moment. Anyway, during his speech, Harin said emphatically that the era of heirs apparent or crown princes was gone for good. People knew that he was alluding to Sajith Premadasa and Namal Rajapaksa (sons of former Presidents hopeful of succeeding Anura Kumara Dissanayake). Harin was seen biting his tongue or sticking it out a little as he was preparing to leave the stage at the end of his address. Was he regretting what he had just said or was he cocking a snook at what, he was sure, was Namal’s ambition that would be revealed in his speech, the rally having been organised by the Pohottuwa or the SLPP? (To be continued)

by Rohana R. Wasala

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoOver 35,000 drug offenders nabbed in 36 days

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoLevel III landslide early warning continue to be in force in the districts of Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala and Matale

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoLOLC Finance Factoring powers business growth

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoCPC delegation meets JVP for talks on disaster response

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoA 6th Year Accolade: The Eternal Opulence of My Fair Lady

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoRising water level in Malwathu Oya triggers alert in Thanthirimale

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Catastrophic Impact of Tropical Cyclone Ditwah on Sri Lanka: