Features

The state of the art: Our cinema

By Uditha Devapriya

(With input from Dhananjaya Samarakoon)

In 1965 the Sri Lankan government published the findings of a Commission of Inquiry into the Film Industry. Filled with proposals and representations from prominent players in the Ceylonese cinema, the Commission made several recommendations. The most important of these was the establishment of a National Film Corporation. Though this would not come to pass until six years later, with the election of a socialist regime committed to a level playing field in the industry, the need for such an institution was frequently underscored.

Among those who made representations to the Commission was Ceylon Theatres. Admitting to the problems of the local cinema, the organisation contended that whether financed by the State or by private players, the film producer “cannot escape the limitations imposed by his audience.” Distinguishing between the cinema and the other arts, it added that while painters, playwrights, novelists, and sculptors could create without paying much regard for the reactions of the masses, the producer remained “the slave of his audience.”

Perhaps the most important point the Commission made was the link between the fortunes of the cinema and the country’s economic problems. Advocating greater intervention in the sector, the centre-left administration which took office in 1970 recognised the problems of allowing a few private players “to virtually control the local film industry.” To that end the new government sought to reduce the influence of monopolistic elements in the market, by regulating the production, distribution, and exhibition of films. Seeking superior production values and greater local output, it tried to give the cinema a new lease of life.

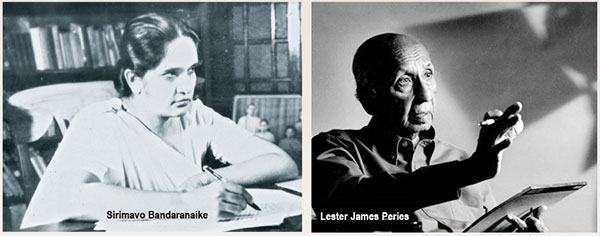

In 1977 the controls enforced by the Sirimavo Bandaranaike administration were loosened. The most immediate result of the new policy was, on the one hand, “ever increasing access to American and Hong Kong productions” and, on the other, the removal of “impediments for newcomers to enter the field.” In other words, from a level playing field, the industry transformed into a business venture. The introduction of television had a considerable say in the reduction of audience numbers that followed, though commentators are divided on the extent to which it led to a fall in cinema hall attendance.

Any examination of the problems and dilemmas of the Sri Lankan cinema must consider these historical developments and shifts. Rather belatedly recognising what should have been acknowledged a long time ago, the Sri Lankan State officially categorised the cinema as an industry late last year. Though this comes too little, too late, it nevertheless behoves us to consider and reflect upon the issues facing the field now, from both administrative and creative standpoints. As always, of course, the link between these issues and the country’s economic problems remains relevant, as much as it did in 1965.

Glancing through the history of the Sri Lankan cinema, from its inception in 1947, we note that the deterioration of creative standards has been rather sharp and dismal. What’s ironic is that despite such a descent, there’s no end to the courses being offered on filmmaking, acting, scriptwriting, and cinematography in the country today. We can conclude that the main contradiction here lies between an ever-fertile reserve of talent and a woeful lack of opportunity for such talent. In other words, we have enough and more talented people. But they lack the money, agency, and access to make full use of their talent.

Part of the reason, which hardly, if at all, gets mentioned by the local commentariat on the cinema, is the absence of an industrial base in the sector. It comes to no surprise that the peak of the Sri Lankan cinema should have been the 1960s and 1970s: these were years in which a flourishing artistic renaissance coincided a not insignificant industrial presence in the film sector. While State intervention became more pronounced under the United Front administration, the existence of a thriving commercial base in the industry ensured a steady stream of not just mainstream, but also artistic productions.

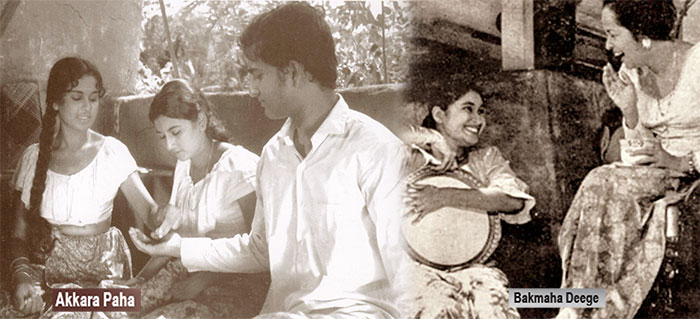

It’s entirely fitting, then, that the cultural revolution heralded by the general election of 1956, which saw a centre-left alliance touting the values of local art forms come to power, should face its peak in these two decades. It’s also fitting that the undisputed doyen of the Sri Lankan cinema, Lester James Peries, should not just make two masterpieces in a row – the highly literate Gamperaliya (1964) and the highly experimental Delovak Athara (1966) – but then follow them up with three further masterpieces, all done for a commercial player, Ceylon Theatres – Golu Hadawatha (1968), Akkara Paha (1969), and Nidhanaya (1970) – in this period. These were years of cultural experimentation, experimentation that benefitted from cultural sectors, especially film, being linked to an industrial framework.

Conversely, the deterioration of the cinema can be traceable to the deterioration of that industrial framework in the country. On the advice of the World Bank, Shiran Ilanperuma writes, the country’s first government “recklessly squandered foreign-currency reserves while avoiding major industrial investment.” Ilanperuma writes that by the 1960s, terms of trade had begun to shift irrevocably, “as the export of primary products and raw materials could not sustain the country’s consumption of imported manufactures.” This had a not insignificant impact on the cinema: by the late 1960s, it was becoming clear that unless the State stepped in, the Ceylonese cinema, for long dependent on an oligopoly of production companies, would collapse. This issue was what the National Film Corporation attempted to address upon its establishment in 1971, as it did over the next few years.

The implementation of swabasha, despite its obvious limitations, also had an impact on the trajectory of the cinema after the 1950s. Though reviled by the English-speaking elite, the empowerment of a Sinhalese-speaking middle-class gave rise to a bilingual intelligentsia, in turn paving the way for a bilingual cultural community. It was from this community that the likes of Dayananda Gunawardena, who gave us the finest adaptation of a French play ever turned into a Sinhalese film, Bakmaha Deege, hailed. While the deterioration of creative and intellectual standards within the population should be admitted, there is no doubt that at its heyday, the Sri Lankan cinema benefitted from a flourishing middle-class.

Today, unfortunately, despite the existence of an upward aspiring and largely Sinhalese middle bourgeoisie, prospects no longer seem good for the local cinema. In any country it is the middle-classes that produce, and reproduce, its cultural elites. In Sri Lanka, though, this community has, however one looks at it, regressed on so many levels, owing mainly to a declining economic situation. We can note the decline of standards in film and television production today, not so much in acting as in scriptwriting and camerawork. We can also note a despairing lack of imagination in films and TV serials: from predictable storylines to endless dialogues, we have come down dismally on so many fronts.

I think the problem has to do with the fact that we no longer explore new themes and issues through the cinema. If we do, we invariably create trends that are imitated and reproduced by a hundred or so other filmmakers and scriptwriters. Ho Gana Pokuna was a brilliant and a highly exceptional film, but it set a precedent for stories about impoverished village schools and idealistic teachers that continue to be filmed, even now. Aloko Udapadi sensationalised audiences and critics, but since its release five years ago we have been making million-rupee budget historical epics which look and feel despairingly predictable.

To be sure, these are hardly any problems specific to only the cinema. When was the last time a cover song didn’t make the rounds online, giving a temporary spotlight to the cover artist while popularising the original tune? When did a mainstream TV series, of which seem to be inundated with these days, not try to cut costs by way of static camera frames and endless expository dialogues? Art exhibitions, especially in Colombo, seem limited to an intellectual upper crust who can afford rental costs in the city and whose work seems not merely cut off from the world around them, but also downright indifferent to it.

We need to acknowledge that there can be no way out for the cinema here unless our cultural industries are linked to a proper industrial framework. In the 1960s, the last peak decade of the three big production companies, Sri Lanka faced an acute terms of trade and structural crisis that the State shielded the cinema from by establishing a Film Corporation and setting high artistic and administrative standards. This did not, to be sure, always work out well, but it did keep the cinema at bay during those difficult days of the 1970s. One can hardly be prudish about the liberalisation of the industry after 1977, but the fact is that the sluggish growth, and then decline, of the cinema remains very much linked to the economic and structural impasses we have been stumbling into since then.

The truth of the matter is that without a proper industrial policy and industrial base, no country’s cinema can be sustained for long. Whether from a creative or an administrative standpoint, the Sri Lankan cinema deserves much more than what it has been subjected to. But where are the policymakers and experts who can prescribe radical solutions, who can recommend an industrialisation plan that can help our cinema take off? In the US, in China, and in India, these problems have been, and are being, combated. In Sri Lanka this does not appear to be the case. That is to be regretted, deeply and sincerely.

(Uditha Devapriya can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com, while Dhananjaya Samarakoon can be reached at dhananjayasmrk@gmail.com)

Features

Pharmaceuticals, deaths, and work ethics

Yet again, deaths caused by questionable quality pharmaceuticals are in the news. As someone who had worked in this industry for decades, it is painful to see the way Sri Lankans must face this tragedy repeatedly when standard methods for avoiding them are readily available. An article appeared in this paper (Island 2025/12/31) explaining in detail the technicalities involved in safeguarding the nation’s pharmaceutical supply. However, having dealt with both Western and non-Western players of pharmaceutical supply chains, I see a challenge that is beyond the technicalities: the human aspect.

There are global and regional bodies that approve pharmaceutical drugs for human use. The Food and Drug Administration (USA), European Medicines Agency (Europe), Medicine and Health Products Regulatory Agency (United Kingdom), and the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (Japan) are the major ones. In addition, most countries have their own regulatory bodies, and the functions of all such bodies are harmonized by the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) and World Health Organization (WHO). We Sri Lankan can take solace in knowing that FDA, the premier drug approval body, came into being in 1906 because of tragedies similar to our own. Following the Elixir Sulfanilamide tragedy that resulted in over one hundred deaths in 1938 and the well-known Phthalidomide disaster in 1962, the role and authority of FDA has increased to ensure the safety and efficacy of the US drug supply.

Getting approval for a new proprietary pharmaceutical is an expensive and time-consuming affair: it can take many billions of dollars and ten to fifteen years to discover the drug and complete all the necessary testing to prove safety and efficacy (Island 2025/01/6). The proprietary drugs are protected by patents up to twenty years, after which anyone with the technical knowhow and capabilities can manufacture the drug, call generics, and seek approval for marketing in countries of their choice. This is when the troubles begin.

Not having to spend billions on discovery and testing, generics manufactures can provide drugs at considerable cost savings. Not only low-income countries, but even industrial countries use generics for obvious reasons, but they have rigorous quality control measures to ensure efficacy and safety. On the other hand, low-income countries and countries with corrupt regulatory systems that do not have reasonable quality control methods in place become victims of generic drug manufacturers marketing substandard drugs. According to a report, 13% of the drugs sold in low-income countries are substandard and they incur $200 billion in economic losses every year (jamanetworkopen.2018). Sri Lankans have more reasons to be worried as we have a history of colluding with scrupulous drug manufactures and looting public funds with impunity; recall the immunoglobulin saga two years ago.

The manufacturing process, storage and handling, and the required testing are established at the time of approval; and they cannot be changed without the regulatory agency’s approval. Now a days, most of the methods are automated. The instruments are maintained, operated, and reagents are handled according to standard operating procedures. The analysts are trained and all operations are conducted in well maintained laboratories under current Good Manufacturing Procedures (cGMP). If something goes wrong, there is a standard procedure to manage it. There is no need for guess work; everything is done following standard protocols. There is traceability; if something went wrong, it is possible to identify where, when, and why it happened.

Setting up a modern analytical laboratory is expensive, but it may not cost as much as a new harbor, airport, or even a few kilometers of new highway. It is safe to assume that some private sector organizations may already have a couple of them running. Affordability may not be a problem. But it is sad to say that in our part of the world, there is a culture of bungling up the best designed system. This is a major concern that Western pharmaceutical companies and regulatory agencies have in incorporating supply chains or services from our part of the world.

There are two factors that foster this lack of work ethics: corruption and lack of accountability. Admirably, the private sector has overcome this hurdle for the most part, but in the public sector, from top to bottom, lack of accountability and corruption have become a pestering cancer debilitating the economy and progress. Enough has been said about corruption, and fortunately, the present government is making an effort to curb it. We must give them some time as only the government has changed, not the people.

On the other hand, lack of accountability is a totally alien concept for our society. In many countries, politicians are held accountable at elections. We give them short breaks, to be re-elected at the next election, often with super majorities, no matter how disastrous their actions were. When it comes to government servants, we have absolutely no way to hold them accountable. There is absolutely no mechanism in place; it appears that we never thought about it.

Lack of accountability refers to the failure to hold individuals responsible for their actions. This absence of accountability fosters a culture of impunity, where corrupt practices can thrive without fear of repercussions. In Sri Lanka, a government job means a lifetime employment. There is no performance evaluation system; promotions and pay increases are built in and automatically implemented irrespective of the employee’s performance or productivity. The worst one can expect for lapses in performance is a transfer, where one can continue as usual. There is no remediation. To make things worse, often the hiring is done for political reasons rather than on merit. Such employees have free rein and have no regard for job responsibilities. Their managers or supervisors cannot take actions as they have their political masters to protect them.

The consequences of lack of accountability in any area at any level are profound. There is no need to go into detail; it is not hard to see that all our ills are the results of the culture of lack of accountability, and the resulting poor work ethics. Not only in the pharmaceuticals arena, but this also impacts all aspects of products and services available. If anyone has any doubts, they should listen to COPE committee meetings. Without a mechanism to hold politicians, government employees, and bureaucrats accountable for their actions or lack of it, Sri Lanka will continue to be a developing country forever, as has happened over the last seventy years. As a society, we must take collective actions to demand transparency, hold all those in public service accountable, and ensure that nation’s resources are used for the benefit of all citizens. The role of ethical and responsible journalism in this respect should not be underestimated.

by Geewananda Gunawardana, Ph.D. ✍️

Features

Tips for great sleep

Although children can sleep well, most adults have trouble getting a good night’s sleep. They go to bed each night, but find it difficult to sleep. While in bed they toss and turn until daybreak. Such people cannot be expected to do any work properly. Upon waking they get ready to go for work, but they feel exhausted. While travelling to workplaces they doze off on buses and trains. In fact sleep deprivation leads to depression. Then they seek medical help to get over the problem.

Some people take sleeping pills without consulting a doctor. Sleeping pills might work for a few days, but you will find it difficult to drag yourself out of bed. What is more, you will feel drowsy right throughout the day. If you take sleeping pills regularly, you will get addicted to them.

A recent survey has revealed that millions of Asians suffer from insomnia – defined as an inability to fall asleep or to sleep through the night. When you do not get enough sleep for a long time, you might need medical treatment. According to a survey by National University Hospital in Singapore, 15 percent of people in the country suffer from insomnia. This is bad news coming from a highly developed country in Asia. It is estimated that one third of Asians have trouble sleeping. As such it has become a serious problem even for Sri Lankans.

Insomnia

Those who fail to take proper treatment for insomnia run the risk of sleep deprivation. A Japanese study reveals that those who sleep five hours or less are likely to suffer a heart attack. A healthy adult needs at least seven hours of sleep every day. When you do not get the required number of hours for sleep, your arteries may be inflamed. Sleep deprived people run the risk of contracting diabetes and weight gain. An American survey reveals that children who do not get deep sleep may be unnaturally small. This is because insomnia suppresses growth hormones.

It is not the length of sleep that matters. The phases of sleep are more important than the number of hours you sleep. Scientists have found that we go through several cycles of 90 minutes per night. Every cycle consists of three phases: light sleep, slumber sleep and dream sleep. When you are in deep sleep your body recuperates. When you dream your mind relaxes. Light sleep is a kind of transition between the two.

Although adults should get a minimum seven hours of sleep, the numbers may vary from person to person. In other words, some people need more than seven hours of sleep while others may need less. After the first phase of light sleep you enter the deep sleep phase which may last a few minutes. The time you spend in deep sleep may decrease according to the proportion of light sleep and dream sleep.

Napoleon Bonaparte

It is strange but true that some people manage with little sleep. They skip the light sleep and recuperate in deep sleep and dream sleep. For instance, Napoleon Bonaparte used to sleep only for four hours a night. On the other hand, we sleep at different times of the day. Some people – known as ‘Larks’ – go to bed as early as 8 p.m. There are ‘night owls’ who go to bed after midnight. Those who go to bed late and get up early are a common sight. Some of them nod off in the afternoon. This shows that we have different sleep rhythms. Dr Edgardo Juan L. Tolentino of the Philippine Department of Health says, “Sleep is as individual as our thumb prints and patterns can vary over time. Go to bed only when you are tired and not because it’s time to go to bed.”

If you are suffering from sleep deprivation, do not take any medication without consulting a doctor. Although sleeping pills can offer temporary relief, you might end up as an addict. Therefore take sleeping pills only on a doctor’s prescription. He will decide the dosage and the duration of the treatment. What is more, do not increase the dose yourself and also do not take them with alcohol.

You need to exercise your body in order to keep it in good form. However, avoid strenuous exercises late in the evening because they would stimulate the body and increase the blood circulation. This does not apply to sexual activity which will pave the way for sound sleep. If you are unable to enjoy sleep, have a good look at your bedroom. The bedroom and the bed should be comfortable. You will also fall asleep easily in a quiet bedroom. Avoid bright lights in the bedroom. Use curtains or blinds to darken the bedroom. Use a quality mattress with proper back support.

Methods

Before consulting a doctor, you may try out some of the methods given below:

* Always try to eat nutritious food. Some doctors advise patients to take a glass of red wine before going to bed. However, too much alcohol will ruin your sleep. Avoid smoking before going to bed because nicotine impairs the quality of sleep.

* Give up the habit of drinking a cup of coffee before bedtime because caffeine will keep you awake. You should also avoid eating a heavy meal before going to bed. A big meal will activate the digestive system and it will not allow the body to wind down.

* Always go to bed with a relaxed mind. This is because stress hormones in the body can hinder sleep. Those who lead stressful lives often have trouble sleeping. Such people should create an oasis between the waking day’s events and going to bed. The best remedy is to go to bed with a novel. Half way through the story you will fall asleep.

* Make it a point to go to bed at a particular time every day. When you do so, your body will get attuned to it. Similarly, try to get up at the same time every day, including holidays. If you do so, such practices will ensure your biological rhythm.

* Avoid taking a long nap in the afternoon. However, a power nap lasting 20 to 30 minutes will revitalise your body for the rest of the day.

* If everything fails, seek medical help to get over your problem.

(karunaratners@gmail.com)

By R.S. Karunatne

Features

Environmental awareness and environmental literacy

Two absolutes in harmonising with nature as awareness sparks interest – Literacy drives change

Hazards teach lessons to humanity.

Before commencing any movement to eliminate or mitigate the impact of any hazard there are two absolutes, we need to pay attention to. The first requirement is for the society to gain awareness of the factors that cause the particular hazard, the frequency of its occurrence, and the consequences that would follow if timely action is not taken. Out of the three major categories of hazards that have been identified as affecting the country, namely, (i) climatic hazards (floods, landslides, droughts), (ii) geophysical hazards (earthquakes, tsunamis), and (iii) endemic hazards (dengue, malaria), the most critical category that frequently affect almost all sectors is climatic hazards. The first two categories are natural hazards that occur independently of human intervention. In most instances their occurrence and behaviour are indeterminable. Endemic hazards are a combination of both climatic hazards and human negligence.

ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS

‘In Ceylon it never rains but pours’ – Cyclone Ditwah and Our Experiences

Climatic hazards, as experienced in Sri Lanka are dependent on nature, timing and volume of rainfall received during a year. The patterns of rainfall received indicate that, in most instances, rainfalls follow a rhythmic pattern, and therefore, their advent and ferocity as well as duration could in most instances be forecast with near accuracy. Based on analyses of long-term mean monthly rainfall data, Dr. George Thambyahpillay (Citation, University of Ceylon Review vol. XVI No. 3 & 4 Jul.-Oct 1958, pp 93-106 1958) produced a research paper wherein he exposed a certain Rainfall Rhythm in Ceylon. He opens his paper with the statement ‘In Ceylon it never rains but it pours’, which clearly shows both the velocity and the quantum of rain that falls in the island. ‘It is an idiom which expresses that ‘when one bad thing happens, a lot of other bad things also happen, making the situation even worse’. How true it is, when we reminisce short and long term impacts of the recent Ditwah cyclone.

Proving the truism of the above phrase we have experienced that many climatic hazards have been associated with the two major seasonal rainy phases, namely, the Southwest and Northeast monsoons, that befall in the two rainy seasons, May to September and December to February respectively. This pattern coincides with the classification of rainy seasons as per the Sri Lanka Met Department; 1) First inter-monsoon season – March-April, 2) Southwest monsoon – May- September, 3) Second Inter-monsoon season – October-November, and 4) Northeast monsoon – December-February.

The table appearing below will clearly show the frequency with which climatic hazards have affected the country. (See Table 1: Notable cyclones that have impacted Sri Lanka from 1964-2025 (60 years)

A marked change in the rainfall rhythm experienced in the last 30 years

An analysis of the table of cyclones since 1978 exposes the following important trends:

(i) The frequency of occurrence of cyclones has increased since 1998,

(ii) Many cyclones have affected the northern and eastern parts of the country.

(iii) Ditwah cyclone diverged from this pattern as its trajectory traversed inland, affecting the entire island. (similar to cyclones Roanu and Nada of 2016).

(iv) A larger number of cyclones occur during the second inter-monsoon season during which Inter-Monsoonal Revolving Storms frequently occur, mainly in the northeastern seas, bordering the Bay of Bengal. Data suggests the Bay of Bengal has a higher number of deadlier cyclones than the Arabian Sea.

(v) Even Ditwah had been a severe cyclonic outcome that had its origin in the Bay of Bengal.

(vi) There were several cyclones in the years 2016 (Roanu and Nada), 2020 (Nivar and Burevi), 2022 (Asani and Mandous) and 2025 (Montha and Ditwah). In 2025, exactly a month before Ditwah, (November 27, 2025) cyclone Montha affected the country’s eastern and northern parts (October 27) – a double whammy.

(vii) Climatologists interpret that Sri Lanka being an island in the Indian Ocean, the country is vulnerable to cyclones due to its position near the confluence of the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean.

(viii) The island registers increased cyclonic activity, especially in the period between October and December.

The need to re-determine the paddy cultivation seasons Yala and Maha vis-a-vis changing rainfall patterns

Sri Lanka had been faithfully following the rainfall patterns year in year out, in determining the Maha and Yala paddy cultivation seasons. The Maha season falls during the North-east monsoon from September to March in the following year. The Yala season is effective during the period from May to August. However, the current changes in the country’s rainfall pattern, would demand seriously reconsidering these seasons numerous cyclones had landed in the past few years, causing much damage to paddy as well as other cultivations. Cyclones Montha and Ditwah followed one after the other.

The need to be aware of the land we live in Our minds constantly give us a punch-list of things to fixate on. But we wouldn’t have ever thought about whether the environments we live in or do our businesses are hazardous, and therefore, that item should be etched in our punch-list. Ditwah has brought us immense sorrow and hardships. This unexpected onslaught has, therefore, driven home the truth that we need to be ever vigilant on the nature of the physical location we live in and carry on our activities. Japanese need not be told as to how they should act or react in an earthquake or a tsunami. Apart from cellphone-indications almost simultaneously their minds would revolve around magnitude of the earthquake and seismic intensity, tsunami, fires, electricity and power, public transportation, and what to do if you are inside a building or if you are outdoors.

Against this backdrop it is really shocking to know of the experiences of both regional administrators and officials of the NBRO (National Building Research Organisation) in their attempts to persuade people to shift to safer locations, when deluges of cyclone Ditwah were expected to cause floods and earth slips/ landslides

Our most common and frequently occurring natural hazards

Apart from the Tsunami (December 26, 2004), that caused havoc in the Northeastern and Southern coastal belts in the country, our two most natural hazards that take a heavy toll on people’s lives and wellbeing, and cause immense damage to buildings, plantations, and critical infrastructure have been periodic floods and landslides. It has been reported that Ditwah has caused ‘an estimated $ 4.1 billion in direct physical damage to buildings, agriculture and critical infrastructure, which include roads, bridges, railway lines and communication links. It is further reported that total damage is equivalent to 4% of the country’s GDP.’

Floods and rain-induced landslides demand high alert and awareness

As the island is not placed within the ‘Ring of Fire’ where high seismic activity including earthquakes and volcanic activity is frequent, Sri Lanka’s notable hazards that occur almost perennially are floods and landslides; these calamities being consequent upon heavy rains falling during both the monsoonal periods, as well as the intermonsoonal periods where tropical revolving storms occur. When taking note of the new-normal rhythm of the country’s rainfall, those living in the already identified flood-basins would need to be ever vigilant, and conscious of emergency evacuation arrangements. Considering the numbers affected and distress caused by floods and disruptions to commercial activities, in the Western province, some have opined that priority would have been given to flood-prevention schemes in the Kelani river basin, over the Mahaweli multi-development programme.

Geomorphic processes carry on regardless, in reshaping the country’s geomorphological landscape

Geomorphic processes are natural mechanisms that eternally shape the earth’s surface. Although endogenic processes originating in the earth’s interior are beyond human control, exogenic processes occur continuously on or near the earth’s surface. These processes are driven by external forces, which mainly include:

(i) Weathering: rock-disintegration through physical, chemical and biological processes, resulting in soil and sediment formation.

(ii) Erosion: Dislocation/ removal and movement of weathered materials by water and wind (as ice doesn’t play a significant role in the Tropics).

(iii) Transportation: The shifting of weathered material to different locations often by rivers, wind, heavy rains,

(iv) Deposition: Transported material being settled forming new landforms, lowering of hills, and flattening of undulated land or depositing in the seabed.

What we witnessed during heavy rains caused by cyclone Ditwah is the above process, what geomorphologists refer to as ‘denudation’. This process is liable to accelerate during spells of heavy rain, causing landslides, landfalls, earth and rock slips/ rockslides and landslides along fault lines.

Hence, denudation is quite a natural phenomenon, the only deviation being that it gets quickened during heavy rains when gravitational and other stresses within a slope exceed the shear strength of the material that forms slopes.

It is, therefore, a must that both people and relevant authorities should be conscious of the consequences, as Ditwah was not the first cyclone that hit the country. Cyclone Roanu in May 2016 caused havoc by way of landslides, Aranayake being an area severely affected.

Conscious data-studies and analyses and preparedness; Two initials to minimise potential dangers

Sri Lanka has been repeatedly experiencing heavy rain–related disasters as the table of cyclones clearly shows (numbering 22 cyclones within the last 60 years). Further, Sri Lanka possesses comprehensive hazard profiles developed to identify and mitigate risks associated with these natural hazards.

A report of the Department of Civil Engineering, University of Moratuwa, says “Rain induced landslides occur in 13 major districts in the central highland and south western parts of the country which occupies about 20-30% of the total land area, and affects 30-38% of total population (6-7.6 Million). The increase of the number of landslides and the affected areas over the years could be attributed to adverse changes in the land use pattern, non-engineered constructions, neglect of maintenance and changes in the climate pattern causing high intensity rainfalls.”

ENVIRONMENTAL LITERACY

Environmental awareness being simply knowing facts will be of no use unless such knowledge is coupled with environmental literacy. Promoting environmental literacy is crucial for meeting environmental challenges and fostering sustainable development. In this context literacy involves understanding ecological principles and environmental issues, as well as the skills and techniques needed to make informed decisions for a sustainable future. This aspect is the most essential component in any result-oriented system to mitigate periodic climate-related hazards.

Environmental literacy rests upon several crucial pillars

The more important pillars among others being:

· Data-based comprehensive knowledge of problems and potential solutions

· Skills to analyse relevant data and information critically, and communicate effectively the revelations to relevant agencies promptly and accurately.

· Identification and Proper interconnectedness among relevant agencies

· Disposition – The attitudes, values and motivation that drive responsible environmental behaviour and engagement.

· Action – The required legal framework and the capacity to effectively translate knowledge, skills and disposition into solid action that benefits the environment.

· Constant sharing of knowledge with relevant international bodies on the latest methods adopted to harmonise human and physical environments.

· Education programmes – integrating environmental education into formal curricula and equipping students with a comprehensive understanding of ecosystems and resource management. Re-structuring the geography syllabus, giving adequate emphasis to environmental issues and changing patterns of weather and overall climate, would seem a priority act.

· Experiential learning – Organising and engaging in field studies and community projects to gain practical insights into environmental conservation.

· Establishing area-wise warning systems, similar to Tsunami warning systems.

· Interdisciplinary Approaches to encourage students to relate ecological knowledge with such disciplines as geology, geography, economics and sociology.

· Establishing Global Collaboration – Leveraging technology and digital platforms to expand access to environmental education and enhance awareness on global environmental issues.

· Educating the farming community especially on the changes occurring in weather and climate.

· Circumventing high and short duration rainfall extremes by modifying cultivation patterns, and introducing high yielding short-duration yielding varieties, including paddy.

· Soil management that reduces soil erosion

· Eradicating misconceptions that environmental literacy is only for scientists (geologists), environmental professionals and relevant state agencies.

A few noteworthy facts about the ongoing climatic changes

1. The year 2025 was marked by one of the hottest years on record, with global

temperatures surpassing 1.5ºC.

2. Russia has been warming at more than twice the global average since 1976, with 2024 marking the hottest year ever recorded.

3. Snowfalls in the Sahara – a rare phenomenon, with notable occurrences recorded in recent years.

4. Monsoon rains in the Indian Subcontinent causing significant flooding and landslides

5. Warming of the Bay of Bengal, intensifying weather activity.

6. The Himalayan region, which includes India, Nepal, Pakistan, and parts of China, experiencing temperatures climbing up to 2ºC above normal, along with widespread above-average rainfall.

7. Sri Lanka experienced rainfall exceeding 300 m.m. in a single day, an unprecedented occurrence in the island’s history. Gammaduwa, in Matale, received 540 m.m. of rainfall on a day, when Ditwah rainfall was at its peak.

The writer could be contacted at kalyanaratnekai@gmail.com

by K. A. I. KALYANARATNE ✍️

Former Management Consultant /

Senior Manager, Publications

Postgraduate Institute of Management,

University of Sri Jayewardenepura,

Vice President, Hela Hawula

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoHealth Minister sends letter of demand for one billion rupees in damages

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoRemembering Douglas Devananda on New Year’s Day 2026

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoDr. Bellana: “I was removed as NHSL Deputy Director for exposing Rs. 900 mn fraud”

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoDons on warpath over alleged undue interference in university governance

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRebuilding Sri Lanka Through Inclusive Governance

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSri Lanka Tourism surpasses historic milestone with record tourist arrivals in 2025