Features

The Nicosia Tragedy – lest such be forgotten

By Capt Elmo Jayawardena

By Capt Elmo Jayawardena

elmojay1@gmail.com

It was a lazy April morning in Bangkok’s Don Muang Airport. The Globe Air Charter flight carrying 120 Swiss and German passengers was about to taxi out for takeoff. The planned journey was long, starting in Thailand and ending up in Switzerland, with re-fueling stops in Colombo, Bombay and Cairo, before flying the last leg to its destination – Basel. The plane carried 10 crew – five in the cabin and five in the cockpit, comprising three pilots and two flight engineers, what they called a heavy crew to fly multi-sector long haul flights. In command was Capt. St Elmo Muller, a Ceylonese pilot who had served in the RAF during the second world war.

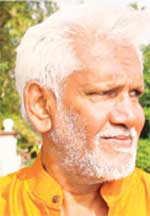

Capt. Muller was born in Colombo and educated at St. Joseph’s College. He learnt to fly as a teenager and obtained an ‘A’ licence at Ratmalana. They say that Muller used to cycle from Colombo to Ratmalana Airport to take his flying lessons from renowned flying instructor, Flight Lieutenant Robert Duncanson. Subsequently, Elmo Muller was one of the first 15 Ceylonese to join the Royal Air Force and leave for training to the UK. Four of the 15 were selected as fighter pilots and Elmo Muller trained to fly heavier bombers. He also flew reconnaissance Spitfires attached to Squadron 543 of the RAF. Having entered the RAF as a Sergeant Pilot he rose to the rank of Flight Lieutenant by 1945, when he was just 24 years of age. His quick rise through the ranks says much about Muller as an officer and a pilot.

After the war, Muller remained in Europe, flew charter aeroplanes for different companies, and served as a commercial pilot with EL AL, the national carrier of Israel.

This was Capt. St Elmo Muller, aged 45, who took off from Bangkok on the19th of April 1967 – an experienced airman with 8285 flying hours, of which 1,493 were logged on Britannia aircraft. The co-pilot was P. Hippenmeyer, aged 24, a Swiss national, with a total of 1860 hours, of which 785 were on Britannia aeroplanes. The extra pilot – Capt. H. M. Day, a 40-year old DC-3 pilot, with 9,680 flying hours to his credit – was not rated on the Britannia, but may have been under training as he had 49 hours on this type. The three pilots together totalled almost 20,000 flying hours. Rated or not, there was a considerable amount of experience in that flight deck. As for the two flight engineers, H. W Saunders and H.J. Geisen, they both held valid Swiss Flight Engineer Licences endorsed to operate Britannias.

This was Capt. St Elmo Muller, aged 45, who took off from Bangkok on the19th of April 1967 – an experienced airman with 8285 flying hours, of which 1,493 were logged on Britannia aircraft. The co-pilot was P. Hippenmeyer, aged 24, a Swiss national, with a total of 1860 hours, of which 785 were on Britannia aeroplanes. The extra pilot – Capt. H. M. Day, a 40-year old DC-3 pilot, with 9,680 flying hours to his credit – was not rated on the Britannia, but may have been under training as he had 49 hours on this type. The three pilots together totalled almost 20,000 flying hours. Rated or not, there was a considerable amount of experience in that flight deck. As for the two flight engineers, H. W Saunders and H.J. Geisen, they both held valid Swiss Flight Engineer Licences endorsed to operate Britannias.

The aeroplane was a 10-year old Bristol Britannia powered by four Wright R-3350 turbo-compound engines. The Britannia was certainly the best British long range aeroplane at the time, fighting for its place among the Boeing Stratocruisers, Douglas DC-6s and the Lockheed Constellations that were built across the Atlantic. The Bristol Britannia was as good a plane as any, ranked alongside the best of aeroplanes until the jets, mainly 707s and DC-8s, took to the skies.

The first sector from Bangkok was uneventful. They had five crew members who could swap places in the flight deck which needed three crew members to man. However, as pilot Day was not qualified on the type, whatever resting Capt. Muller did, needed to happen while seated at the Captain’s seat; not the best manner to rest, but a common practice among long haul operators. Doubtless, the journey from Bangkok to Basel, with its three mandatory stops, required great endurance from Capt. Muller. As for the others, they would have managed their in-flight rest periods to stay fresh and focused for the shifts they had to work.

The first sector from Bangkok was uneventful. They had five crew members who could swap places in the flight deck which needed three crew members to man. However, as pilot Day was not qualified on the type, whatever resting Capt. Muller did, needed to happen while seated at the Captain’s seat; not the best manner to rest, but a common practice among long haul operators. Doubtless, the journey from Bangkok to Basel, with its three mandatory stops, required great endurance from Capt. Muller. As for the others, they would have managed their in-flight rest periods to stay fresh and focused for the shifts they had to work.

Being late April with the South West monsoon active in Ceylon the Britannia would have landed on Runway (R/W) 22 in Colombo. The crew likely stretched their legs while the plane re-fueled, before setting off for Santa Cruz Airport in Bombay. That sector would have been the shortest in the flight plan and the easiest to fly. It was bright day light, and the track was over land with adequate navigational beacons for route corrections, dotted with en-route alternates across western India in case of an emergency.

By the time the Globe Air Britannia reached Bombay, they had flown two sectors of the four they were to fly and likely clocked over 10 hours of duty time. Duty time includes the 90 minutes of pre-flight preparation and another 30 – in some companies, 60 – minutes of post flight work.

Several factors influence the calculation of flight time and duty time. Suffice it to say that by the time they were to land in Cairo after the nine-hour leg from Bombay, the crew would have well exceeded their duty time limitations. However, this was an unscheduled charter, and it was 1967. It may not have been considered a mortal sin to stretch the limits of duty time. After all, they had five crew members to share the workload.

Departing Bombay, the Britannia took off with 11 hours and 10 minutes’ fuel endurance for the nine-hour flight. Capt. Muller headed west crossing the Arabian Sea to enter Omani Airspace. This was the longest leg of the trip – destination Cairo, the penultimate stop before Basel. I do not know the exact route they flew, but they would have flown over the Middle Eastern Emirates and Saudi Arabia, and past the Eastern Mediterranean to reach Cairo. By this time, the crew would have been on duty for over 20 hours and Capt. Muller, in command, would have been confined to his seat throughout except for his toilet breaks. That the crew was fatigued is doubtless; the limit for a present-day modern jet, flying a three-pilot operation, is around 12 hours.

As the Britannia approached Cairo, the weather gods played their Ace of Trumps. The airport was covered with thunderstorms and arriving pilots diverted to safe havens around the edge of the Mediterranean looking for alternates to land. Globe Air Britannia, after flying nine hours from Bombay, probably had approximately two hours of fuel left in the tanks when Capt. Muller made his decision to divert. The designated alternate for Globe Air was Beirut. The weather there was good – calm winds with one Okta (1/8th of the sky) of cumulus clouds. Cairo being equidistant from Beirut and Nicosia, just a little over 300 nautical miles, Capt. Muller opted to re-nominate Nicosia airport as his preferred alternate and headed to Cyprus.

Nicosia Airport was forecasting intermittent weather with thunderstorms. Capt Muller was no fool; he was a very experienced pilot. He must have had very good reasons for choosing Nicosia. The question remains unanswered why Capt. Muller did not divert to Beirut. I can only surmise, of course, that there might have been other aircraft diverting to Beirut from Cairo. The congestion may have been a reason why Capt. Muller decided to go to Nicosia as he could not have had the comfort of adequate fuel to go into a long holding pattern in Beirut.

There is no doubt that Capt. Muller made a professionally reasoned Commander’s decision to land in Nicosia. Given his experience and in the absence of evidence to the contrary, we can determine that the decision to go to Nicosia would have been made for very valid reasons. We must remember that a Captain diverting an aeroplane after a long flight may not have the luxury of time.

I do not know why the Britannia diverted to Nicosia. I will leave it at that. Let me get on with the story.

At 2215 GMT, other aeroplanes in the area heard Globe Air calling Nicosia. Beirut heard it too and passed a message to Nicosia Control that Globe Air was making attempts to contact them. At 2300 Nicosia Approach talked to Globe Air and gave them the latest weather report. With 5/8 of the sky around the Nicosia aerodrome covered with thunderstorms, this was always going to be a difficult arrival. The airport did not have an Instrument Landing System (ILS) and was only fitted with a VOR for a non-precision approach. Globe Air came over the airfield at 2306 and was cleared for a right hand downwind to approach on R/W 32. At 2310 the Britannia reported it was over the R/W 32 threshold but as it was slightly high, the Captain executed a missed approach. The Tower then cleared Globe Air for a left-hand downwind circuit for R/W 32. Capt. Muller accepted the clearance and said he would fly a low-level visual circuit, doing his best to keep the runway in sight on his left.

At 2215 GMT, other aeroplanes in the area heard Globe Air calling Nicosia. Beirut heard it too and passed a message to Nicosia Control that Globe Air was making attempts to contact them. At 2300 Nicosia Approach talked to Globe Air and gave them the latest weather report. With 5/8 of the sky around the Nicosia aerodrome covered with thunderstorms, this was always going to be a difficult arrival. The airport did not have an Instrument Landing System (ILS) and was only fitted with a VOR for a non-precision approach. Globe Air came over the airfield at 2306 and was cleared for a right hand downwind to approach on R/W 32. At 2310 the Britannia reported it was over the R/W 32 threshold but as it was slightly high, the Captain executed a missed approach. The Tower then cleared Globe Air for a left-hand downwind circuit for R/W 32. Capt. Muller accepted the clearance and said he would fly a low-level visual circuit, doing his best to keep the runway in sight on his left.

The Swiss registered HB-ITB Britannia that Capt. Muller was flying did not have a Flight Recorder fitted. The airport did not have RADAR to track the path of the aeroplane. The only evidence available after the accident for investigations were the Air Traffic Control tapes, which recorded the communications between Globe Air and the Tower. The last message on tape was the pilot stating he was doing a low-level circuit. Sitting at my desk, more than fifty years later, I can only give careful consideration to all the circumstances and make an educated guess as to what happened next.

The Britannia was probably flying at 1000 feet, maybe 800 ft, on a left-hand downwind heading of 140 degrees. The dark midnight sky was covered with 5 oktas of thundery cumulonimbus, the visibility further reduced by rain. I picture Capt. Muller looking out of the left window to keep the runway in sight, as well as scanning his flight instruments to stay on track, speed and altitude. His fuel too may not have been much, as he started with 11 hours and 10 minutes from Bombay and burnt nine hours to get to Cairo. The diversion to Nicosia would have cost him another hour of fuel and the missed approach he executed in Nicosia may have burnt at least another 10 minutes of the precious little left. Capt. Muller was likely sitting on less than one hour’s worth of fuel when he was flying the low-level circuit: not enough to go anywhere except Nicosia.

In addition to all these calamitous facts, St Elmo Muller had sat on his Captain’s seat for more than 22 hours. If ever a deck was stacked against an Airline Captain, this was it.

45 seconds after passing the R/W 32 threshold, the Britannia commenced its left turn to the base leg heading of 050, which would have brought it perpendicular to R/W 32.

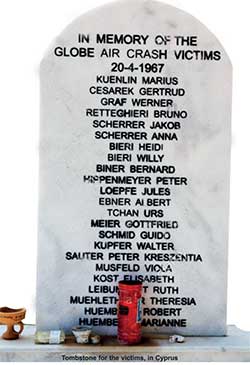

It was then, at 2313, that the left wing of the aeroplane hit the side of a hill at a height of 820 ft, 22 feet below the crest. The heading at point of impact was 068 degrees, the aircraft still turning to 050, the base leg heading. The wing broke and the aircraft rolled and hit another hillock, bursting into flames and killing 126 of the occupants. Almost impossibly, four survived, three of them severely injured. The fourth walked away from the crash without a scratch.

“The accident resulted from an attempt to make an approach at a height too low to clear rising ground.” That was the conclusion of the Nicosia Civil Aviation Authority after their investigation.

Without the information from a flight recorder it is difficult to know what really happened. The conclusions from different sources who were associated with the investigations are rather contradictory. As with most airline crashes, none of the flight crew lived to tell the tale.

Capt. St Elmo Muller’s remains were brought to Ceylon in a sealed coffin and placed in the Muller family vault at the Kanatte Cemetery.

I sincerely hope what I wrote would bring memories of an honourable Ceylonese aviator who should be remembered.

The truth of what happened on that fateful night remains lost forever on a Cypriot hill.

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result for this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

Features

Egg white scene …

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

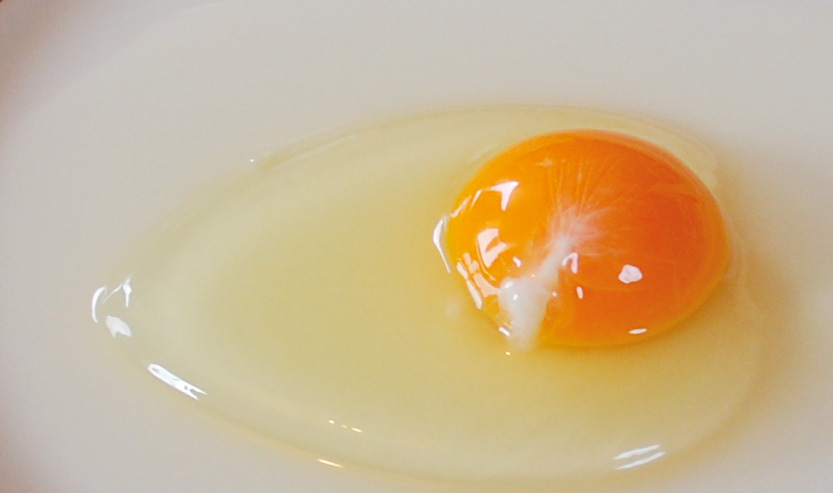

Thought of starting this week with egg white.

Yes, eggs are brimming with nutrients beneficial for your overall health and wellness, but did you know that eggs, especially the whites, are excellent for your complexion?

OK, if you have no idea about how to use egg whites for your face, read on.

Egg White, Lemon, Honey:

Separate the yolk from the egg white and add about a teaspoon of freshly squeezed lemon juice and about one and a half teaspoons of organic honey. Whisk all the ingredients together until they are mixed well.

Apply this mixture to your face and allow it to rest for about 15 minutes before cleansing your face with a gentle face wash.

Don’t forget to apply your favourite moisturiser, after using this face mask, to help seal in all the goodness.

Egg White, Avocado:

In a clean mixing bowl, start by mashing the avocado, until it turns into a soft, lump-free paste, and then add the whites of one egg, a teaspoon of yoghurt and mix everything together until it looks like a creamy paste.

Apply this mixture all over your face and neck area, and leave it on for about 20 to 30 minutes before washing it off with cold water and a gentle face wash.

Egg White, Cucumber, Yoghurt:

In a bowl, add one egg white, one teaspoon each of yoghurt, fresh cucumber juice and organic honey. Mix all the ingredients together until it forms a thick paste.

Apply this paste all over your face and neck area and leave it on for at least 20 minutes and then gently rinse off this face mask with lukewarm water and immediately follow it up with a gentle and nourishing moisturiser.

Egg White, Aloe Vera, Castor Oil:

To the egg white, add about a teaspoon each of aloe vera gel and castor oil and then mix all the ingredients together and apply it all over your face and neck area in a thin, even layer.

Leave it on for about 20 minutes and wash it off with a gentle face wash and some cold water. Follow it up with your favourite moisturiser.

Features

Confusion cropping up with Ne-Yo in the spotlight

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

At an official press conference, held at a five-star venue, in Colombo, it was indicated that the gathering marked a defining moment for Sri Lanka’s entertainment industry as international R&B powerhouse and three-time Grammy Award winner Ne-Yo prepares to take the stage in Colombo this December.

What’s more, the occasion was graced by the presence of Sunil Kumara Gamage, Minister of Sports & Youth Affairs of Sri Lanka, and Professor Ruwan Ranasinghe, Deputy Minister of Tourism, alongside distinguished dignitaries, sponsors, and members of the media.

According to reports, the concert had received the official endorsement of the Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau, recognising it as a flagship initiative in developing the country’s concert economy by attracting fans, and media, from all over South Asia.

However, I had that strange feeling that this concert would not become a reality, keeping in mind what happened to Nick Carter’s Colombo concert – cancelled at the very last moment.

Carter issued a video message announcing he had to return to the USA due to “unforeseen circumstances” and a “family emergency”.

Though “unforeseen circumstances” was the official reason provided by Carter and the local organisers, there was speculation that low ticket sales may also have been a factor in the cancellation.

Well, “Unforeseen Circumstances” has cropped up again!

In a brief statement, via social media, the organisers of the Ne-Yo concert said the decision was taken due to “unforeseen circumstances and factors beyond their control.”

Ne-Yo, too, subsequently made an announcement, citing “Unforeseen circumstances.”

The public has a right to know what these “unforeseen circumstances” are, and who is to be blamed – the organisers or Ne-Yo!

Ne-Yo’s management certainly need to come out with the truth.

However, those who are aware of some of the happenings in the setup here put it down to poor ticket sales, mentioning that the tickets for the concert, and a meet-and-greet event, were exorbitantly high, considering that Ne-Yo is not a current mega star.

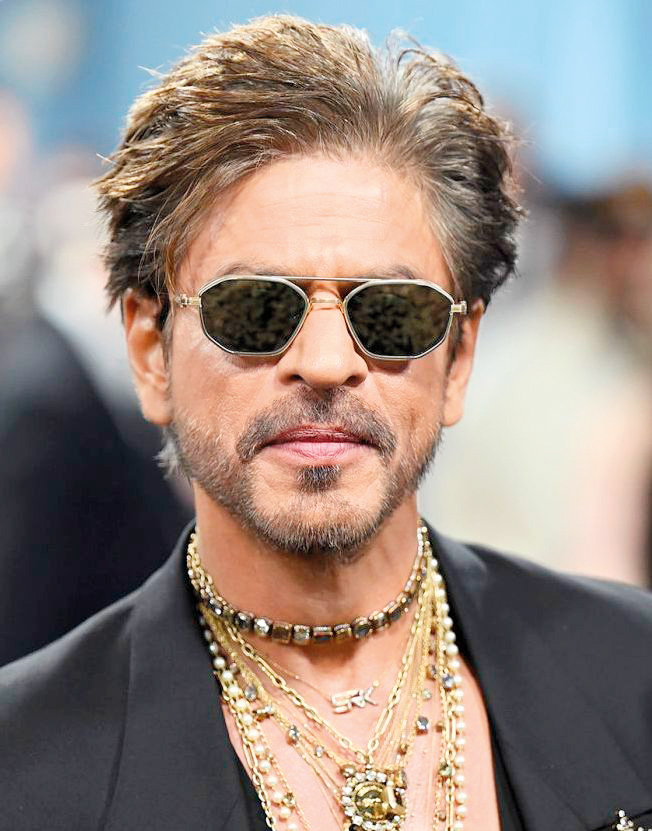

We also had a cancellation coming our way from Shah Rukh Khan, who was scheduled to visit Sri Lanka for the City of Dreams resort launch, and then this was received: “Unfortunately due to unforeseen personal reasons beyond his control, Mr. Khan is no longer able to attend.”

Referring to this kind of mess up, a leading showbiz personality said that it will only make people reluctant to buy their tickets, online.

“Tickets will go mostly at the gate and it will be very bad for the industry,” he added.

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoLankan aircrew fly daring UN Medevac in hostile conditions in Africa

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRethinking post-disaster urban planning: Lessons from Peradeniya

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoAre we reading the sky wrong?

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo