Features

Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part VIII

(Part VII of this article appeared on 18 April, 2025)

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa: Glamorous Entry and Ignominious Exit

After Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s victory in the November 2019 presidential election and the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna’s (SLPP) landslide win in the August 2020 parliamentary elections, Sri Lanka’s political landscape underwent another drastic shift. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s popularity peaked during the parliamentary elections, helping the SLPP secure nearly a two-thirds majority. However, in a dramatic volte-face of events within just two years, ‘Gota-mania’ had turned into a ‘Gota-phobia’. The five-year period from the 2019 presidential election to the landmark 2024 presidential election, which brought the National People’s Power (NPP) to power, was marked by a series of dramatic political events, including the Aragalaya—intense popular agitations that signified an unprecedented shift in the country’s political culture.

From the outset, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa had to face the challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to the postponement of parliamentary elections. Without parliamentary oversight, he implemented health measures to manage the health crisis, resulting in excessive executive aggrandizement. In October 2020, Parliament passed the 20th Amendment, reversing the democratic reforms of the 19th Amendment. As the country grappled with the economic fallout of the global pandemic, certain decisions taken by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa further deepened the crisis, pushing the economy to the brink of collapse.

After 2019, Sri Lanka’s domestic and international political environment began to change significantly. The previously cordial atmosphere of dialogue and accommodation with the UNHRC was reversed. In February 2020, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa announced Sri Lanka’s decision to withdraw its co-sponsorship of the UNHRC resolutions previously agreed upon by the former administration. This move drew strong international criticism, particularly from Western nations. Despite this, Sri Lanka assured the UNHRC that it remained committed to achieving sustainable peace through an inclusive, domestically led reconciliation and accountability process. The shifting political climate was reflected in UNHRC Resolution 46/1, adopted in March 2021, which, for the first time, acknowledged the need to preserve, analyse, and consolidate evidence of human rights violations and abuses in Sri Lanka for potential future prosecutions. On February 14, 2020, the U.S. State Department announced a travel ban on Sri Lankan Army Commander Lieutenant General Shavendra Silva, his immediate family, and several other military officers. The ban was imposed on the grounds of command responsibility for “gross violations of human rights,” specifically extrajudicial killings at the end of Sri Lanka’s civil war.

Foreign policy under President Gotabaya Rajapaksa was largely shaped by the pressing domestic challenges his administration faced, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic and the worsening economic crisis. As the country grappled with severe financial instability, mounting debt, and declining foreign reserves, Rajapaksa’s government sought closer ties with nations that could provide economic relief, including China and India. Growing public dissatisfaction and protests over economic mismanagement influenced foreign policy decisions. Finally, Sri Lanka’s foreign policy under President Gotabaya Rajapaksa was driven more by necessity than strategic vision, reflecting the urgent need to address domestic crises.

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s decisions, driven by domestic political pressure from his Sinhala nationalist clientele, undermined Sri Lanka’s credibility with key international partners. His rejection of the US Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) grant and the Japan-funded Light Railway Transit (LRT) project exemplify this trend. By rejecting the MCC grant, the President prioritised political narratives over economic benefits. His government framed the MCC as a threat to sovereignty, aligning with nationalist sentiments, even though it was a no-strings-attached grant. The unilateral cancellation of the JICA-funded LRT project without prior consultation with Japan further strained relations. Japan is one of Sri Lanka’s biggest development partners, and scrapping such a significant project without negotiation damaged diplomatic and economic ties. This decision not only led to the loss of a beneficial urban transport system but also risked future funding from Japan. It signaled to international donors that Sri Lanka was an unreliable partner. These actions reflected short-term political maneuvering rather than a strategic approach to economic development and foreign policy.

Since January 2022, all major economic indicators declined sharply, triggering a new wave of public protests. People from all walks of life took to the streets in tendon to protest the rising cost of living, prolonged power cuts, fuel shortages that led to days-long queues, exploding gas cylinders, and the scarcity of essential goods such as milk powder, food, and medicine. Alongside these grievances, the protests also brought unprecedented attention to longstanding issues of economic mismanagement. It took a new turn with the setting up of Gota-Go-Gamga in front of the Presidential Secretariat on April 9th. With no viable alternatives, the Sri Lankan government declared its first-ever sovereign default on April 12, 2022—marking the country’s first default since gaining independence in 1948. It was too late to prevent the deepening economic and political crisis from reaching total collapse. Nevertheless, the Aragalaya cannot be understood merely as a spontaneous uprising driven by economic hardship. From a broader perspective, it marked the beginning of a new phase in the crisis of the post-war Sri Lankan state

The Aragalaya and Ranil Wickremesinghe’s Interlude as interim President

The Aragalaya that forced President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to flee the country in disgrace and send his resignation from overseas on 14 July 2022 was arguably the most consequential political phenomenon in post-war Sri Lanka. It effectively ended the Rajapaksa family’s dominance in national politics and set in motion political dynamics that will shape the country’s trajectory for years to come. As a complex and multifaceted movement, its true impact cannot be measured by immediate outcomes alone; a long-term perspective is essential to fully understand its significance. One of its most striking effects was the unprecedented rise of the JVP/NPP, which, having previously secured only 3% of the popular vote, achieved a historic victory in the 2024 presidential and parliamentary elections.

In the aftermath of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s Resignation, Ranil Wickremesinghe was elected as interim President by a Parliament still dominated by the SLPP led by Mahinda Rajapaksa. By the time President Ranil Wickremesinghe mobilised heavy military forces to decisively crack down on Gota-Go-Gama on July 22, 2022 and prevent a section of protesting youths moving towards parliament, the protesters were debating on how to end their protest. By orchestrating a dramatic show of power, Wickremesinghe positioned himself as the saviour of the nation, claiming credit for restoring stability and preventing Sri Lanka from descending into anarchy and economic collapse. However, this narrative allowed him to consolidate power while the Rajapaksa political establishment remained intact in the background. After four months long dramatic events, the country seemed to have returned to the status quo ante.

The international community was stunned by the magnitude and intensity of the protest. All the key international actors were concerned about the direction of Aragalaya. As there were many actors and dispersed leadership to Aragalaya, it was not possible for any external power to influence the outcome single handedly. The protest movement itself decided its course on its own. However, Ranil Wickremesinghe’s modus operandi raises the question of whether he leveraged the Aragalaya to secure his own political future. History is full of sudden twists and turns, but in the long run, one twist often negates another.

The Aragalaya brought the ‘people’ factor to the forefront of international relations, emphasizing that global governance is no longer solely about diplomacy among political elites but increasingly about responding to popular demands. It challenged traditional diplomatic narratives that prioritize state stability over public welfare. As a result, foreign governments, international financial institutions, and regional organisations were compelled to engage with the concerns of the people. India extended emergency credit lines to Sri Lanka, international media amplified the voices of protesters, and global financial institutions like the IMF considered public sentiment in bailout negotiations. This demonstrates how grassroots movements can influence international discourse and shape policy decisions.

The impact of Aragalaya was further amplified by digital platforms, transforming it into a global phenomenon. Social media enabled real-time updates, mobilisation, and international awareness, drawing attention from human rights organisations, foreign governments, and diaspora communities. This digital interconnectedness highlights the growing role of ordinary people—not just governments—in shaping international relations. The Aragalaya serves as a powerful reminder that citizens are not passive subjects of global affairs but active agents capable of influencing political and economic decisions worldwide.

The Aragalaya brought global attention to corruption and economic mismanagement, emphasising their direct impact on governance, human rights, and international relations. Corruption, once seen as a domestic issue managed within national legal frameworks, is now increasingly recognised as a fundamental governance failure with far-reaching consequences. This shift was evident in the comprehensive report submitted by United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, to the 51st session of the Human Rights Council in September 2022. In her report, she addressed the link between economic crimes and Sri Lanka’s economic crisis, expressing hope that the new administration would respond to public demands for accountability, particularly for corruption and abuses of power, with a renewed commitment to ending impunity.

After Sri Lanka withdrew from co-sponsoring the UNHRC resolution in 2020, its relations with Western powers deteriorated—a trend continued under President Ranil Wickremesinghe too. In October 2022, the UNHRC adopted Resolution 51/1, which, for the first time, established the Sri Lanka Accountability Project (SLAP) under the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to collect evidence of alleged violations. In November 2022, a group of British parliamentarians called for measures beyond UNHRC resolutions, urging sanctions—including asset freezes and travel bans—against alleged Sri Lankan war criminals and their referral to the International Criminal Court. Even before UNHRC Resolution 51/1, on February 14, 2020, under President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the U.S. blacklisted General Shavendra Silva and imposed a travel ban on him. In January 2023, Canada imposed sanctions on former presidents Mahinda Rajapaksa and Gotabaya Rajapaksa for their involvement in “gross and systematic violations of human rights” during the armed conflict. In September 2023, twelve bipartisan members of the U.S. Congress urged the State Department to hold Sri Lanka legally accountable under the ‘UN Convention against Torture’. On March 25, 2025, Britain also imposed a travel ban on three Sri Lankan ex-generals, including General Shavendra Silva, and a former LTTE commander from the east, who later switched loyalties and supported the Sri Lankan Army.

The primary focus of foreign policy under President Ranil Wickremesinghe was guiding Sri Lanka out of its default status. As Acting President on July 18, 2022, Wickremesinghe turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and initiated negotiations for a bailout package. Under his leadership, Sri Lanka reached a staff-level agreement with the IMF for an Extended Fund Facility (EFF) program. This effort culminated in March 2023, when the country successfully secured a board-level agreement, marking a significant step toward economic recovery. After intense negotiations with the Official Creditor Committee (OCC)—which includes major bilateral lenders such as Japan, India, and France—along with the China Exim Bank, Sri Lanka finalized debt restructuring agreements on June 26, 2024. These agreements, totaling USD 10 billion, were reached with key bilateral creditors, including the OCC and China Exim Bank.

One of the other key priorities of President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s foreign policy has been attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to boost Sri Lanka’s economic recovery. India was the first country to come forward to help Sri Lanka in early 2022 and provided extensive assistance totaling approximately USD 4 billion, encompassing various forms of support such as multiple credit lines and currency assistance, notably an agreement to supply petroleum worth USD 700 million through a Line of Credit. Additionally, export credit facilities totaling USD 1.5 billion were extended for the import of essential commodities, facilitated by India’s EXIM Bank and the State Bank of India.

Since then, India’s involvement in Sri Lanka’s economy has surged, solidifying its position as the main trading partner. In August 2022, the Indian Rupee (INR) was designated as an international currency in Sri Lanka. The deepening engagement of India was particularly evident in the power and renewable energy sectors.

In February 2023, Adani Green Energy received approval to invest $442 million in developing 484 megawatts of wind power capacity in Mannar town and Pooneryn village in northern Sri Lanka. This investment, along with a 20-year power purchase agreement with India’s Adani Green, further cements India’s influence over Sri Lanka’s energy sector. In March 2024, Sri Lanka signed an agreement with U Solar Clean Energy Solutions of India to construct hybrid renewable energy systems on three northern coastal islands—Delft, Analativu, and Nainativu. This project is backed by an $11 million grant from India, reinforcing its commitment to Sri Lanka’s renewable energy development.

At a time when Sri Lanka desperately needed foreign investment, the India-China rivalry became evident in the country’s plans to develop container terminals at the Colombo harbor. China had already built the Colombo International Container Terminal (CICT) with a $500 million investment and held an 85% stake in its operations. Meanwhile, India and the United States were increasingly concerned about China’s growing presence in both the Hambantota port and Colombo harbor. In response, the Wickremesinghe government offered the West Container Terminal to India instead of the East Container Terminal. This move was seen as an attempt to balance strategic competition between India and China in the Indian Ocean. However, rather than a well-calibrated foreign policy, it appears more like strategic promiscuity —leveraging Sri Lanka’s strategic assets solely to attract foreign investment.

When the National People’s Power (NPP) Government assumed power following Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s victory in the presidential elections on 21 September 2024 and secured a two-thirds majority in the parliamentary elections on 14 November 2024, the country’s foreign policy was in total disarray, lacking clear direction. Given the strategic importance of foreign relations in statecraft—particularly in the context of regional dynamics, Indian Ocean geopolitics, and evolving global power shifts—it became imperative for the new administration to redefine Sri Lanka’s foreign policy. It is a formidable challenge that requires accurately identifying foreign policy priorities, selecting viable strategies as a small island state, and advancing them prudently while carefully assessing critical strategic developments in regional and global political spheres.

by Gamini Keerawella

(To be concluded)

Features

Crucial test for religious and ethnic harmony in Bangladesh

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

The apprehensions are mainly on the part of religious and ethnic minorities. The parliamentary poll of February 12th is expected to bring into existence a government headed by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Islamist oriented Jamaat-e-Islami party and this is where the rub is. If these parties win, will it be a case of Bangladesh sliding in the direction of a theocracy or a state where majoritarian chauvinism thrives?

Chief of the Jamaat, Shafiqur Rahman, who was interviewed by sections of the international media recently said that there is no need for minority groups in Bangladesh to have the above fears. He assured, essentially, that the state that will come into being will be equable and inclusive. May it be so, is likely to be the wish of those who cherish a tension-free Bangladesh.

The party that could have posed a challenge to the above parties, the Awami League Party of former Prime Minister Hasina Wased, is out of the running on account of a suspension that was imposed on it by the authorities and the mentioned majoritarian-oriented parties are expected to have it easy at the polls.

A positive that has emerged against the backdrop of the poll is that most ordinary people in Bangladesh, be they Muslim or Hindu, are for communal and religious harmony and it is hoped that this sentiment will strongly prevail, going ahead. Interestingly, most of them were of the view, when interviewed, that it was the politicians who sowed the seeds of discord in the country and this viewpoint is widely shared by publics all over the region in respect of the politicians of their countries.

Some sections of the Jamaat party were of the view that matters with regard to the orientation of governance are best left to the incoming parliament to decide on but such opinions will be cold comfort for minority groups. If the parliamentary majority comes to consist of hard line Islamists, for instance, there is nothing to prevent the country from going in for theocratic governance. Consequently, minority group fears over their safety and protection cannot be prevented from spreading.

Therefore, we come back to the question of just and fair governance and whether Bangladesh’s future rulers could ensure these essential conditions of democratic rule. The latter, it is hoped, will be sufficiently perceptive to ascertain that a Bangladesh rife with religious and ethnic tensions, and therefore unstable, would not be in the interests of Bangladesh and those of the region’s countries.

Unfortunately, politicians region-wide fall for the lure of ethnic, religious and linguistic chauvinism. This happens even in the case of politicians who claim to be democratic in orientation. This fate even befell Bangladesh’s Awami League Party, which claims to be democratic and socialist in general outlook.

We have it on the authority of Taslima Nasrin in her ground-breaking novel, ‘Lajja’, that the Awami Party was not of any substantial help to Bangladesh’s Hindus, for example, when violence was unleashed on them by sections of the majority community. In fact some elements in the Awami Party were found to be siding with the Hindus’ murderous persecutors. Such are the temptations of hard line majoritarianism.

In Sri Lanka’s past numerous have been the occasions when even self-professed Leftists and their parties have conveniently fallen in line with Southern nationalist groups with self-interest in mind. The present NPP government in Sri Lanka has been waxing lyrical about fostering national reconciliation and harmony but it is yet to prove its worthiness on this score in practice. The NPP government remains untested material.

As a first step towards national reconciliation it is hoped that Sri Lanka’s present rulers would learn the Tamil language and address the people of the North and East of the country in Tamil and not Sinhala, which most Tamil-speaking people do not understand. We earnestly await official language reforms which afford to Tamil the dignity it deserves.

An acid test awaits Bangladesh as well on the nation-building front. Not only must all forms of chauvinism be shunned by the incoming rulers but a secular, truly democratic Bangladesh awaits being licked into shape. All identity barriers among people need to be abolished and it is this process that is referred to as nation-building.

On the foreign policy frontier, a task of foremost importance for Bangladesh is the need to build bridges of amity with India. If pragmatism is to rule the roost in foreign policy formulation, Bangladesh would place priority to the overcoming of this challenge. The repatriation to Bangladesh of ex-Prime Minister Hasina could emerge as a steep hurdle to bilateral accord but sagacious diplomacy must be used by Bangladesh to get over the problem.

A reply to N.A. de S. Amaratunga

A response has been penned by N.A. de S. Amaratunga (please see p5 of ‘The Island’ of February 6th) to a previous column by me on ‘ India shaping-up as a Swing State’, published in this newspaper on January 29th , but I remain firmly convinced that India remains a foremost democracy and a Swing State in the making.

If the countries of South Asia are to effectively manage ‘murderous terrorism’, particularly of the separatist kind, then they would do well to adopt to the best of their ability a system of government that provides for power decentralization from the centre to the provinces or periphery, as the case may be. This system has stood India in good stead and ought to prove effective in all other states that have fears of disintegration.

Moreover, power decentralization ensures that all communities within a country enjoy some self-governing rights within an overall unitary governance framework. Such power-sharing is a hallmark of democratic governance.

Features

Celebrating Valentine’s Day …

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Merlina Fernando (Singer)

Yes, it’s a special day for lovers all over the world and it’s even more special to me because 14th February is the birthday of my husband Suresh, who’s the lead guitarist of my band Mission.

We have planned to celebrate Valentine’s Day and his Birthday together and it will be a wonderful night as always.

We will be having our fans and close friends, on that night, with their loved ones at Highso – City Max hotel Dubai, from 9.00 pm onwards.

Lorensz Francke (Elvis Tribute Artiste)

On Valentine’s Day I will be performing a live concert at a Wealthy Senior Home for Men and Women, and their families will be attending, as well.

I will be performing live with romantic, iconic love songs and my song list would include ‘Can’t Help falling in Love’, ‘Love Me Tender’, ‘Burning Love’, ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight’, ‘The Wonder of You’ and ‘’It’s Now or Never’ to name a few.

To make Valentine’s Day extra special I will give the Home folks red satin scarfs.

Emma Shanaya (Singer)

I plan on spending the day of love with my girls, especially my best friend. I don’t have a romantic Valentine this year but I am thrilled to spend it with the girl that loves me through and through. I’ll be in Colombo and look forward to go to a cute cafe and spend some quality time with my childhood best friend Zulha.

JAYASRI

Emma-and-Maneeka

This Valentine’s Day the band JAYASRI we will be really busy; in the morning we will be landing in Sri Lanka, after our Oman Tour; then in the afternoon we are invited as Chief Guests at our Maris Stella College Sports Meet, Negombo, and late night we will be with LineOne band live in Karandeniya Open Air Down South. Everywhere we will be sharing LOVE with the mass crowds.

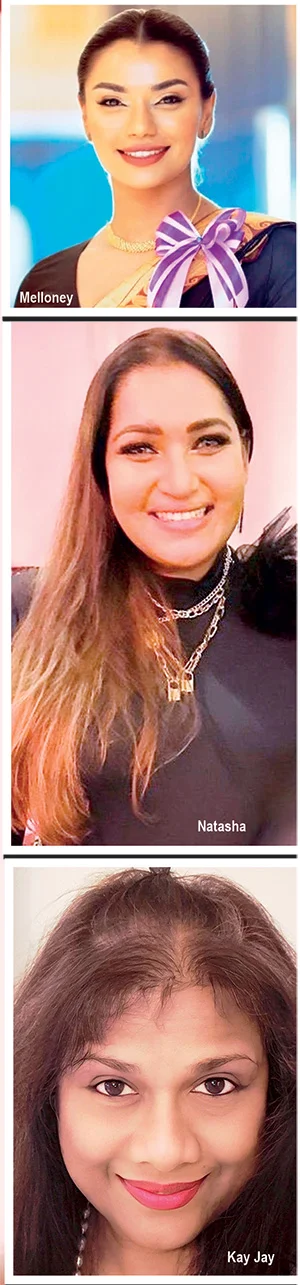

Kay Jay (Singer)

I will stay at home and cook a lovely meal for lunch, watch some movies, together with Sanjaya, and, maybe we go out for dinner and have a lovely time. Come to think of it, every day is Valentine’s Day for me with Sanjaya Alles.

Maneka Liyanage (Beauty Tips)

On this special day, I celebrate love by spending meaningful time with the people I cherish. I prepare food with love and share meals together, because food made with love brings hearts closer. I enjoy my leisure time with them — talking, laughing, sharing stories, understanding each other, and creating beautiful memories. My wish for this Valentine’s Day is a world without fighting — a world where we love one another like our own beloved, where we do not hurt others, even through a single word or action. Let us choose kindness, patience, and understanding in everything we do.

Janaka Palapathwala (Singer)

Janaka

Valentine’s Day should not be the only day we speak about love.

From the moment we are born into this world, we seek love, first through the very drop of our mother’s milk, then through the boundless care of our Mother and Father, and the embrace of family.

Love is everywhere. All living beings, even plants, respond in affection when they are loved.

As we grow, we learn to love, and to be loved. One day, that love inspires us to build a new family of our own.

Love has no beginning and no end. It flows through every stage of life, timeless, endless, and eternal.

Natasha Rathnayake (Singer)

We don’t have any special plans for Valentine’s Day. When you’ve been in love with the same person for over 25 years, you realise that love isn’t a performance reserved for one calendar date. My husband and I have never been big on public displays, or grand gestures, on 14th February. Our love is expressed quietly and consistently, in ordinary, uncelebrated moments.

With time, you learn that love isn’t about proving anything to the world or buying into a commercialised idea of romance—flowers that wilt, sweets that spike blood sugar, and gifts that impress briefly but add little real value. In today’s society, marketing often pushes the idea that love is proven by how much money you spend, and that buying things is treated as a sign of commitment.

Real love doesn’t need reminders or price tags. It lives in showing up every day, choosing each other on unromantic days, and nurturing the relationship intentionally and without an audience.

This isn’t a judgment on those who enjoy celebrating Valentine’s Day. It’s simply a personal choice.

Melloney Dassanayake (Miss Universe Sri Lanka 2024)

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I’m incredibly blessed because, for me, every day feels like Valentine’s Day. My special person makes sure of that through the smallest gestures, the quiet moments, and the simple reminders that love lives in the details. He shows me that it’s the little things that count, and that love doesn’t need grand stages to feel extraordinary. This Valentine’s Day, perfection would be something intimate and meaningful: a cozy picnic in our home garden, surrounded by nature, laughter, and warmth, followed by an abstract drawing session where we let our creativity flow freely. To me, that’s what love is – simple, soulful, expressive, and deeply personal. When love is real, every ordinary moment becomes magical.

Noshin De Silva (Actress)

Valentine’s Day is one of my favourite holidays! I love the décor, the hearts everywhere, the pinks and reds, heart-shaped chocolates, and roses all around. But honestly, I believe every day can be Valentine’s Day.

It doesn’t have to be just about romantic love. It’s a chance to celebrate love in all its forms with friends, family, or even by taking a little time for yourself.

Whether you’re spending the day with someone special or enjoying your own company, it’s a reminder to appreciate meaningful connections, show kindness, and lead with love every day.

And yes, I’m fully on theme this year with heart nail art and heart mehendi design!

Wishing everyone a very happy Valentine’s Day, but, remember, love yourself first, and don’t forget to treat yourself.

Sending my love to all of you.

Features

Banana and Aloe Vera

To create a powerful, natural, and hydrating beauty mask that soothes inflammation, fights acne, and boosts skin radiance, mix a mashed banana with fresh aloe vera gel.

To create a powerful, natural, and hydrating beauty mask that soothes inflammation, fights acne, and boosts skin radiance, mix a mashed banana with fresh aloe vera gel.

This nutrient-rich blend acts as an antioxidant-packed anti-ageing treatment that also doubles as a nourishing, shiny hair mask.

* Face Masks for Glowing Skin:

Mix 01 ripe banana with 01 tablespoon of fresh aloe vera gel and apply this mixture to the face. Massage for a few minutes, leave for 15-20 minutes, and then rinse off for a glowing complexion.

* Acne and Soothing Mask:

Mix 01 tablespoon of fresh aloe vera gel with 1/2 a mashed banana and 01 teaspoon of honey. Apply this mixture to clean skin to calm inflammation, reduce redness, and hydrate dry, sensitive skin. Leave for 15-20 minutes, and rinse with warm water.

* Hair Treatment for Shine:

Mix 01 fresh ripe banana with 03 tablespoons of fresh aloe vera gel and 01 teaspoon of honey. Apply from scalp to ends, massage for 10-15 minutes and then let it dry for maximum absorption. Rinse thoroughly with cool water for soft, shiny, and frizz-free hair.

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Midweek Review2 days ago

Midweek Review2 days agoA question of national pride