Features

Sri Lanka’s Dry Zone; a Misnomer, and its repercussions

By Dr. J. Handawela

jameshandawela@gmail.com

Background

Since Independence the key development policy pursued by the Lankan government has been large scale irrigated paddy farming in the Dry zone (DZ), in the hope of ushering in the same prosperity of its past, particularly the Parakramabahu era (1153-1186). Perakum Yugayak Nevathath Arambaw was a widely flown rhetoric. However, even by about 1985, when the much banked on mighty Mahaweli irrigation project was almost complete, there were no clear signs of the expecte prosperity ever dawning, prompting some citizens to feel skeptical about the whole approach followed to develop the DZ, and thereby the country. I am one of them and see the reason for it as the authorities considering the DZ as being plagued by dryness, farming there requiring additional water as an external input.

In 1994, after leaving formal employment bound to the government, opportunities came on my way to gain a clearer understanding of the DZ’s climate, particularly its implications on agriculture on DZ land. These opportunities, experienced for the first time in my career life as a student of soil science, took me into remote parts of the DZ, spared by the bulldozer that had ripped off DZ’s land to launch major paddy irrigation schemes in all peripheral DZ districts. There, I could see signs of a range of traditional land development measures applied to enable farming, both in a ruined state and in live form. Where it was live, I saw the environment and life there being pleasantly close to nature and safe and sound unlike in major paddy irrigation project lands I had been long accustomed to.

Excitement caused by seeing them evoked an interest in me to seek authentic knowledge on social and farming history of DZ, over and above genuine praise showered on it by local senior farmers. I read Mahawansa and writings of R.L. Brohier, Robert Knox, Leonard Woolf, Emerson Tennent , D L O Mendis, M.S. Randhawa etc., all for the first time in my life, deeply regretting not having read them before.

Following is a gist of what I learned, much of which newly.

Traditional DZ farming has been heavily reliant on local rainfall, received during the main rainy season from October to December and the minor one in April. It has been a highly successful habitat development and farming enterprise.

It has been crucial for it to commence with the onset of rain in October, not only because it broke the four month long rainless weather but also to benefit from the atmospheric character in October over the area which is highly favourable for seed germination and plant growth. The latter reason is implicit in the Sinhala term for October, Vap, which means (time for) seed sowing. Of the two types of crop fields the farmers had: upland Hena and lowland paddy plot, where the farmers first rushed to with the onset of rain was the former for obvious reasons, letting the latter wait until it had also received some runoff and seepage water from adjacent upland and become fully water secure for a crop of paddy.

Though much welcome, the seasonal rain is often too harsh for direct use, as it is, for cropping. Its high intensity causing soil erosion and heavy rains falling over two to three straight days causing flood need to be addressed, and the impacts mitigated and overcome. For that the farmers had chosen individual small watersheds which offered a suitable land base to confront rain, tame its harshness and harness its water for farming, all within their confines. This enabled hazard free farming when it rained and where it rained, without having to forego early rainy time from the cropping calendar or to provide for undue storage and transmission (water) losses we hear of in conventional irrigation.

Specific rain water management measures applied within small watersheds are earthen bunds falling into four types: (1) slender long strips of bund (Wetiya) on the upper aspects of the watershed to delay runoff build-up and slow down runoff flow rate, (2) gulley plugs across transient stream channels to hold up water as water holes ( Wala), (3) further down the stream channel, bunds to hold relatively larger volumes of water Wila and at the very bottom of the small watershed, a larger and stronger bund to hold even more water, both on land surface and in the ground around and beneath it Wewa. All four devices have provision for surplus water to flow out, without hurting the bunds.

Worth reiterating, the unique land layout of the small watershed provides the ideal physical landscape structure to apply the above mentioned measures to delay runoff initiation, slow down runoff flow, check soil erosion and give more time for water to seep into the soil and the ground below, particularly in association with Wewa. They enable commencing upland cropping with early rains, growing of crops fully relying on local rainwater, and equally importantly, generating a ground water resource from rain water.

Crop production could be extended beyond October-December rainy season by choosing crops adapted to lower soil moisture conditions. In some years, it could extend to link up with shorter duration April rains, enabling a cropping period of about eight months. Farmers grew a variety of crops producing a basket of food staples (not only rice) for year round use. The ground water resource generated saw them through the rain water scarce months June-September. All these, thanks to judicious management of rain water, on time and in-situ.

Above observations point to the realization that the wet seasons, October- December and April deserve full credit as characterizing the climate of the DZ, adding value to it and making their beneficial effects felt through the whole climatic year: crops from October- May and ground water, year round.

What matters most is the wisdom the ancient farmers had to understanding that the DZ was wet, at least adequately and not full scale dry. Perhaps it is this wisdom that had brought prosperity to the area, at a time when irrigated paddy farming was little known, prior to initiation of Rajarata kingdom, as reported by archaeaologists Roland Silva and Shiran Deraniyagala ,separately.

Look at the successful farming enterprise in Jaffna, which is even less wet than the inland DZ but manages with local rain, with no need for extraneous water. The reason behind is natural shallow aquifers, which store surplus rain water as a ready source of water for farmer use during the dry months. This makes Jaffna not lament over dryness but appreciate and enjoy its wetness. Ancient DZ farmers, whose soil was less porous to take in rain water and had no natural aquifers, had overcome those limitations by giving more time for rain water to seep into their soil of low porosity and creating an artificial ground water storage facility in association with Wewa in the farmed small watershed.

By the way the term Wewa, being a derivative from “Wapi” – Sanskrit term for water- well, is not a spring or a source of water for flood irrigating a downstream crop as many of us take it to be. It in Sri Lanka is a well of some sort that has created its own ground water support base. In Gujarat, India where the very term Wew is in use, it refers to large wells dug into deep ground water, and they are for community use and habitat enrichment and categorically not for irrigation.

What is stated above is an ideal transcending from my personal experience and observations on a topic of interest and concern to me. Key inferences possible from it are that the climate of DZ is more wet than dry, the ancient farmers saw it in correct perspective and made a success of it, but the modern DZ developers have caught the wrong end of the stick. I want to share these thoughts with like minded researchers with a view to reassessing our current knowledge and understanding of DZ’s climate and its bearing on farming on its land. Emphasize that this is not a simple matter to shrug off but to be concerned with as a real issue with serious repercussions.

DZ ; a misnomer

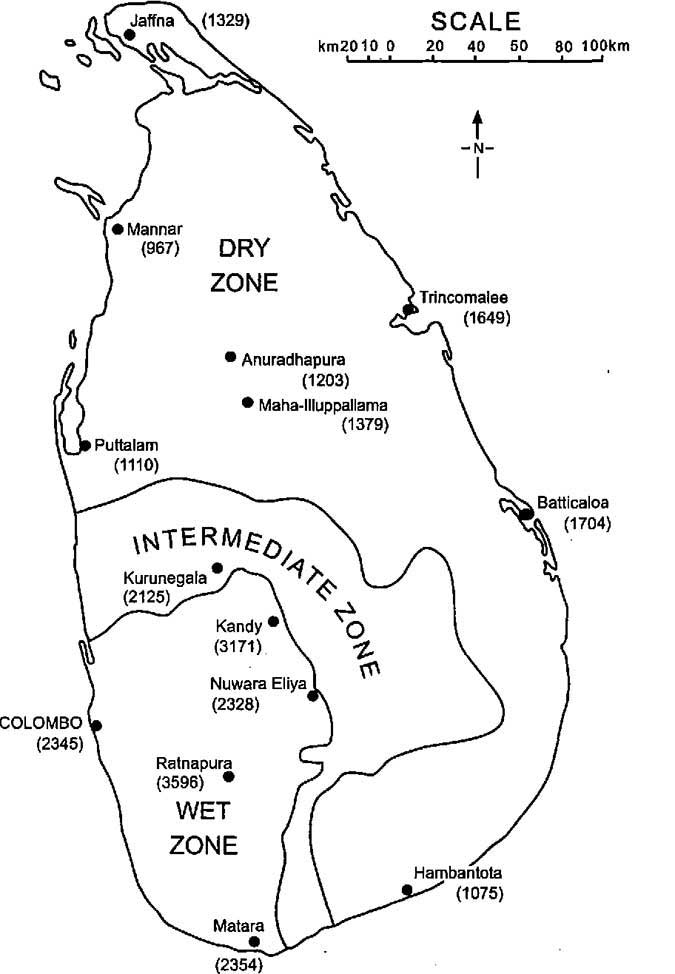

For an area to be called dry its potential evapotranspiration over the year must exceed annual average rainfall. On this account the Sri Lanka’s DZ is not dry. Though not as wet as the Wet Zone, its annual average rainfall of about 1500 mm is only 25% less than the lower end annual rainfall figure for the Wet Zone, making it 75% as wet as the latter, and hence not its exact opposite.

This rain, though somewhat limited to four months, October – December and April, its residual effect is long lasting rendering the whole period from October to May quite wet during which its evergreen natural vegetation, symbolic of wet environments, not showing any major sign of withering. This leaves only four months June- September with a semblance of dryness.

DZ’s relief with soft contours shows that what has shaped its terrain is wetness and not dryness. In dry environments the contours are rugged.

Common climate related hazards in the area are soil erosion by runoff and damage to crop, property and even death by drowning by flooding, all of them problems associated with wet environments. Drought related incidents like forest fires, heat waves, death from desiccation etc. are very rare.

Most visitors to Sri Lanka see it as a green island. They would not say so if they saw two thirds of its land which make up the DZ as dry.All these point to DZ’s climate being more wet than dry, with the wet months October-December showing up as its most characteristic and hence the climate defining season, affirming that the term DZ is a misnomer for the area referred to by it.

Repercussions

The modern developers, who chose to focus on DZ’s dryness which is a mere negativity – deficiency of water – as its diagnostic character and the key limitation to its development over its wetness, which is a positivity – abundance of much desired water, though fraught with risks which however could be overcome by judicious management as discussed above – may not have foreseen its serious repercussions. The more serious of them are;

Spurning of DZ’s wetness-reliant traditional farming, which is a unique system of indigenously evolved watershed farming as being primitive, destructive on forest etc. denying it policy support and access to new scientific knowledge on modern farming has led to its degeneration and extinction with no prospect for its survival. This is a clear case of elimination and eradication of a valued heritage.

A key component of the above system of farming is Hena farming, It has been singled out and unjustifiably blacklisted as being utterly destructive on forest, more strictly subjected to severely restrictive regulations against its practice. Dereliction of such a farming system, that is so well adapted to the DZ environment and when wisely practiced is not only productive but also supportive of local ecology can lead to its extinction.

Overemphasis on dryness focused farming has led to excessive forest clearing to make provision for accumulation and application of water as an external farm input has also led to supply shortages of local timber, locally grown non-rice foods, rapid decline in forest cover, worsening human- elephant conflict etc.

Most farmers provided with water for free as an external input too fall into the category of state subsidy dependent population, casting doubts as to whether they are net producers relative to heavy investment made on them and ecosystem sacrificed to support them. Statistical records show that contribution made to GDP from districts where such farming is widespread is very low.

In the DZ drainage system, primary valleys are the source points of stream water. When their wet weather hydrology is properly managed for wetness-reliant farming, downstream flooding gets mitigated. This helps downstream land use. Modern management measures designed on the basis that the DZ is dry consider upstream small watersheds as unworthy of management and best left as mere catchments to extract water, without involving them even as stakeholders in rain water harnessing. Its repercussions are increased downstream flood hazard during rain and worsened water scarcity during dry weather, particularly in drier years.

Modern dryness-focused farming need time to accumulate and store runoff water in reservoirs, during which farming is not possible. Farming time thus lost is the month of October, which amounts to the most favourable time for crop establishment (Vap) being lost to farming, utter loss of once in a year opportunity.

All these repercussions are due to trying to adapt to dryness, to fill a deficiency gap, to eliminate a negativity. Instead, if the effort had been directed to dwelling on the main rainy season, banking on its positivities: abundance of water, favourable atmospheric character in October for crop establishment, they may have been avoided. Whether the culprit behind this mishap is the term DZ warrants attention.

Recently UN Climatologists Have come out with a clear assertion, that of the two extreme climatic incidents, namely drought and flood, experienced in a given environment, what really needs to be overcome is flood hazard while drought is a problem that could and should be endured instead of struggling to deal with it. It appears that the ancient DZ farmers had followed it centuries ago.

Conclusion

In conclusion let me present a relevant case study extracted from a newspaper article. Thanthirimale in Anuradhapura district has been a traditional farming village where local rain had been well utilized for farming. It had a system of well managed upstream watersheds and a downstream Wewa, and paddy lands below it. This was modernized in 1950s, by letting the upstream watersheds go into abandonment to merely serve/sub-serve as unmanaged water catchment area for the downstream Wewa, which was widened and capacity increased to provide irrigation water to an expanded paddy acreage below it, now not mainly for the customary Maha season but also for the Yala season as well (hopefully).

A knowledgeable senior farmer there says that prior to modernization the community there raised a variety of crops with rain, had adequate food and enough of forest products including timber, seldom faced floods or drinking water scarcity. After modernization, food production got limited to paddy farming below the Wewa, flooding became more frequent and intense because the upstream area had no control over its runoff water. Water stress during dry months, particularly in less wet years, became more acute because all land upstream of the Wewa no longer subscribed to local ground water resource development.

He says the current system that focuses on mitigating (a seeming) drought is less effective than the traditional system which made the most out of the wetness of the rainy season by slowing down water loss as runoff, mitigating local flooding, commencing cropping at the very beginning (Vap) of the rainy season and continued even beyond the rainy season, and saving a share of water as ground water in every small watershed in and around their Wew. In addition it mitigated downstream flooding during times of very high rainfall and also enabled a better dry weather base flow in the stream that left the area.Therefore, it appears that the term DZ has given a distorted meaning to the climate of the so called DZ and misled the modern day DZ developers. An issue that deserves scientific attention.

(The author has been a researcher attached to the Department of Agriculture from 1968-1994 and thereafter an independent researcher. Holds B.Sc (Agriculture) degree from Peradeniya University and Ph.D. (Agriculture) from Kyoto University, Japan.)

Features

Trump tariffs and their effect on world trade and economy with particular reference to Sri Lanka

In the early hours of April 2, 2025, President Donald Trump stood before a crowd of supporters and declared it “Liberation Day” for American workers and manufacturers. He signed an order imposing a minimum 10% tariff on all US imports, with significantly higher rates, ranging from 11% to 50%, on goods from 57 specific countries. This dramatic policy shift sent immediate shockwaves through global markets and trade networks, marking a profound escalation of the protectionist agenda that has defined Trump’s economic philosophy since the 1980s.

The implications of these tariffs extend far beyond America’s borders, rippling through the intricate web of global trade relationships that have been carefully constructed over decades of economic integration. While Trump frames these measures as necessary corrections to trade imbalances and vital protections for American industry, the truth is, it’s way more complicated than that. These tariffs aren’t just minor tweaks to trade rules, they could totally upend the way global trade works in the global economic order, disruptions that will be felt most acutely by developing economies that have built their growth strategies around export-oriented industries.

Among these vulnerable economies stands Sri Lanka, still recovering from a devastating economic crisis that led to sovereign default in 2022. With the United States serving as Sri Lanka’s largest export destination, accounting for 23% of its total exports and a whopping 38% of Sri Lanka’s key textile and apparel exports, the sudden imposition of a 44% tariff rate threatens to undermine the country’s fragile economic recovery. Approximately 350,000 Sri Lankan workers are directly employed in the textile industry. These tariffs aren’t some far-off policy, they are an immediate threat to their livelihoods and economic security.

The story of Trump’s tariffs and their impact on Sri Lanka offers a compelling window into the broader tensions and power imbalances that characterise the global trading system. It illustrates how decisions made in Washington can dramatically alter economic trajectories in distant corners of the world, often with little consideration for the human consequences. It also raises profound questions about the sustainability of development models predicated on export dependency and the adequacy of international financial institutions’ approaches to debt sustainability in developing economies.

This article examines the multifaceted implications of Trump’s tariff policies, tracing their evolution from his first administration through to the present day and analysing their projected impacts on global trade flows and economic growth. It then narrows its focus to Sri Lanka, exploring how the country’s unique economic circumstances and trade profile make it particularly vulnerable to these tariff shocks.

Finally, it considers potential mitigation strategies and policy responses that might help Sri Lanka navigate these turbulent waters, offering recommendations for both immediate crisis management and longer-term structural adaptation.

As we embark on this analysis, it is worth remembering that behind the economic statistics and trade figures lie real human lives and communities whose futures hang in the balance. The story of Trump’s tariffs is ultimately not just about trade policy or economic theory but about the distribution of opportunity and hardship in our interconnected global economy.

TRUMP’S TARIFF POLICIES: PAST AND PRESENT

Historical Context of Trump’s Protectionist Views

Donald Trump’s embrace of protectionist trade policies did not begin with his presidency. Since the 1980s, Trump has consistently advocated for import tariffs as a tool to regulate trade and retaliate against foreign nations that he believes have taken advantage of the United States. His economic worldview was shaped during a period when Japan’s rising economic power was perceived as a threat to American manufacturing dominance. In interviews from that era, Trump frequently criticised Japan for “taking advantage” of the United States through what he characterised as unfair trade practices.

This perspective has remained remarkably consistent throughout his business career and into his political life. Trump views international trade not as a mutually beneficial exchange but as a zero-sum competition where one country’s gain must come at another’s expense. This framework fundamentally shapes his approach to tariffs, which he sees not as taxes ultimately paid by American consumers and businesses (as most economists argue) but as penalties paid by foreign countries for their supposed transgressions against American economic interests.

First Term (2017-2021) Tariff Policies

When President Trump took office in January 2017, he quickly began implementing the protectionist agenda he had promised during his campaign. His administration withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership on his third day in office, signalling a dramatic shift away from the multilateral trade liberalisation that had characterised American policy for decades.

The first major tariffs came in January 2018, when Trump imposed duties of 30-50% on imported solar panels and washing machines. While significant, these were merely the opening salvos in what would become a much broader trade offensive. In March 2018, citing national security concerns under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, Trump announced tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminium imports from most countries. These tariffs initially exempted several allies, including Canada, Mexico, and the European Union, but by June 2018, these exemptions were revoked, straining relationships with America’s closest trading partners.

The most consequential trade action of Trump’s first term, however, was the escalating tariff war with China. Beginning in July 2018, the administration imposed a series of tariffs on Chinese goods, eventually covering approximately $370 billion worth of imports. These measures were justified under Section 301 of the Trade Act, based on allegations of intellectual property theft and forced technology transfer. China responded with retaliatory tariffs on American exports, particularly targeting agricultural products from politically sensitive regions.

By the end of President Trump’s first term, the average US tariff rate had risen from 1.6% to approximately 13.8% on Chinese imports and 3% overall, the highest level of protection since the 1930s. While a “Phase One” trade deal with China in January 2020 paused further escalation, most of the tariffs remained in place, becoming a persistent feature of the international trading landscape.

Current Tariff Policies (2024-2025)

President Trump’s return to the White House in 2025 has brought an even more aggressive approach to tariffs. During his campaign, he promised tariffs of 60% on all Chinese imports, 100% on Mexico, and at least 20% on all other countries. While the actual implementation has not precisely matched these campaign pledges, the scale and scope of the new tariffs have nevertheless been unprecedented in modern American trade policy.

The centrepiece of Trump’s current trade policy was announced on April 2, 2025, dubbed “Liberation Day” by the administration. The executive order imposed a minimum 10% tariff on all US imports, effective April 5, with significantly higher tariffs on imports from 57 specific countries scheduled to take effect on April 9. These country-specific tariffs range from 11% to 50%, with China facing the highest rate at 145% or rather 245%, effectively cutting off most trade between the world’s two largest economies.

The formula for determining these “reciprocal tariffs” remains somewhat opaque, but appears to be based primarily on bilateral trade deficits, with countries running larger surpluses with the United States facing higher tariff rates. This approach reflects Trump’s persistent view that trade deficits represent “losing” in international commerce, a perspective at odds with mainstream economic thinking, which generally views trade balances as the result of broader macroeconomic factors rather than evidence of unfair trade practices.

For Sri Lanka, the formula resulted in a punishing 44% tariff rate, the sixth highest among all targeted countries. This places Sri Lankan exports at a severe competitive disadvantage in the American market, threatening an industry that has been central to the country’s economic development strategy for decades.

The stated objectives of these tariffs include reducing the US trade deficit, revitalising American manufacturing, punishing countries perceived as engaging in unfair trade practices, and generating revenue that Trump has variously suggested could fund infrastructure, childcare subsidies, or even replace income taxes entirely. However, economic analyses from institutions like the World Trade Organisation, the Penn Wharton Budget Model, and numerous independent economists suggest these objectives are unlikely to be achieved, and that the tariffs will instead reduce economic growth both domestically and globally while raising prices for American consumers.

After a violent reaction in financial markets, the administration announced a 90-day pause on the higher country-specific tariffs for all nations, except China. However, the baseline 10% tariff remains in effect, and the threat of the higher tariffs continues to create significant uncertainty in global markets. This uncertainty itself acts as a drag on economic activity, as businesses delay investment decisions and reconsider supply chain arrangements in anticipation of potential future trade disruptions.

GLOBAL ECONOMIC IMPACT OF TRUMP TARIFFS

The imposition of sweeping tariffs by the Trump administration has sent ripples throughout the global economy, with international organisations, economic research institutions, and financial markets all signalling significant concerns about their far-reaching consequences. What began as a unilateral policy decision by the United States threatens to fundamentally alter global trade patterns, disrupt supply chains, and potentially trigger a broader economic slowdown that could affect billions of people worldwide.

WTO Projections on Global Trade Contraction

The World Trade Organisation (WTO), the primary international body overseeing global trade rules, has issued stark warnings about the impact of Trump’s tariffs. In its latest assessment of the global trading system, the WTO dramatically revised its trade growth projections for 2025. Prior to the tariff announcements, the organisation had forecast a healthy 2.7% expansion in global trade for the year. Following Trump’s “Liberation Day” declaration, it now projects a 0.2% contraction, a negative swing of nearly three percentage points.

This contraction in trade is expected to have direct consequences for global economic growth as well. The WTO has downgraded its global GDP growth forecast from 2.8% to a more anaemic 2.2%. While this may seem like a modest reduction, in absolute terms, it represents hundreds of billions of dollars in lost economic activity and potentially millions of foregone jobs worldwide.

Of particular concern to the WTO is the potential “decoupling” of the world’s two largest economies. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the WTO’s director general, has expressed specific alarm about this phenomenon, noting that trade between the United States and China is expected to plunge by 81-91% without exemptions for tech products, such as smartphones. Such a dramatic reduction in bilateral trade between these economic giants would be “tantamount to a decoupling of the two economies” with “far-reaching consequences” for global prosperity and stability.

The WTO has also modelled more severe scenarios that could materialise if the currently paused “reciprocal tariffs” are reimposed after their 90-day hiatus. In such a case, the organisation projects a steeper 0.8% decline in global goods trade. Should this be accompanied by a surge in “trade policy uncertainty” worldwide, as other countries adjust their own policies in response, the WTO suggests an even more severe 1.5% contraction in trade could occur, with global GDP growth potentially falling to just 1.7%, a level that would place many countries perilously close to recession.

by Ali Sabry

(To be continued)

Features

The Broken Promise of Lankan Cinema: Asoka and Swarna’s Thrilling Melodrama – Part I

“‘Dr. Ranee Sridharan,’ you say. ‘Nice to see you again.’The woman in the white sari places a thumb in her ledger book, adjusts her spectacles and smiles up at you. ‘You may call me Ranee. Helping you is what I am assigned to do,’ she says. ‘You have seven moons. And you have already waisted one.’” The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka (London: Sort of Books, 2022. p84)

The very first Sinhala film Broken Promise (1947), produced in a studio in South India, was a plucky endeavour on the part of the multi-ethnic group who powered it. Directed by B.A.W. Jayamanne, it introduced the classically trained Tamil singer and stage actress in the Minerva Theatre Company, Daisy Rasamma Daniels, as Rukmani Devi, (who was the only real star of the Lankan cinema at the height of its mass popularity), to an avid cinephile audience of Ceylon who had grown up enjoying Hindi, Tamil and Hollywood films. The producer of the film, S. M. Nayagam, an Indian of Tamil ethnicity, skilfully negotiated the production of the first Lankan film in Sinhala in his South Indian film studio in Madurai because Ceylon had neither the film infrastructure nor the technical know-how to do so. A Tamil singer/actress and a Sinhala director were the Ceylonese ‘capital’, both of whom had to learn on the run, the craft of filmmaking.

Rukmani Devi and Swarna Mallawarachchi

There is a rather strange parallel between the Tamil Rukmani Devi, playing Sinhala women throughout her entire career with impeccable professionalism, great devotion and love, and the Sinhala Swarna Mallawarachchi, playing a Tamil woman for the first time, in Rani, but quite late in her career. In terms of their careers as independent, self-made film actors these are, undoubtedly, professional achievements of cultural significance for our multi-ethnic, highly stratified, Island nation with its 28-year war. But Rukmani Devi’s career began with the very inception of Lankan cinema when she was quite young and ended all too soon, when she was no longer young enough to play lead roles. However, she continued to earn a living singing at live carnival variety shows, until her tragic death in her 50s.

But Asoka Handagama’s Rani arrives in the era of digital cinema when the mass audience for cinema had diminished greatly, given the easy access online. Also, the Sinhala cinema as an Industry, such as it was, with production, distribution and exhibition of films in cinemas across the country, at scale, and the film-culture that sustained it for several decades does not exist any longer. It’s mostly only Hollywood blockbusters and a handful of films that draw an audience to a theatre. Scandal and controversy play well to draw folk into a cinema sometimes and a brilliant actor can also do this. The example of Australian actress Cate Blanchett becoming a Hollywood star, in Tar (2023), comes to mind. Now most Hollywood films go straight to Netflix and other streaming services with a short theatrical season. And Indian independent cinema and TV series do get on to Netflix with their high production values, unique genre traditions, star systems and a large diaspora for films in several Indian languages – Tamil, Hindi, Telugu.

Swarna’s over 50-year acting career, now in her 70s, has had a very rare boost going by the controversial public reception of the film and its related box office success. However, that this success is the result of having played a remarkable Lankan Tamil woman, a professional, appears not to be of much interest to the many Sinhala critics I have read or heard online. Apart, of course, from a mention in passing that Manorani Sarvanamuttu was a doctor with a patrician, Tamil, Anglophone ancestry, her Tamil ethnicity does not figure centrally in the discussions of the film and of Swarna’s performance itself. In fact, apart from the adulation of her performance as Rani, I have not found as yet any substantive intellectual discussion of her choice of a style of acting and of its aesthetic quality and indeed the politics it implies. As an actress with a highly distinguished filmography, beginning with Siri Gunasinghe’s Sath Samudura (66), with major auteurs of Lankan cinema, this is indeed a strange omission.

In this piece I am particularly interested to explore Swarna and Asoka’s choice of ‘a Melodramatic Style’ of acting, to represent Dr Manorani Saravanamuttu as Rani. She who was a Tamil, Christian, professional woman who, after her son’s assassination, chose to become a public figure, leading a movement of largely Southern, Sinhala-Buddhist women in ‘The Mothers’ Front’ demanding justice for their ‘disappeared’ loved ones during a period of terror in the country.

Tear-Gas Cinema People

I am also thinking of the 2022 ‘Aragalaya/Porattam/Struggle-generation’ in particular, who would have a keen interest in Rani for political and ethical reasons and more specifically all those brilliant protestors who joyfully constructed the ‘Tear Gass Cinema’ in the heart of Galle Face, which was torn down by thugs instigated by Mahinda Rajapaksa himself who appears in Rani as an aspiring politician who cunningly uses the Mothers’ Front to power his political future. As cinephiles, they would no doubt be also interested in the film’s aesthetics, its realpolitik, gender politics and psycho-sexual violence, in an era of all-pervasive terror.

Manorani’s Tamil Ethnicity

Manorani’s Tamil ethnicity and its implications will be at the forefront of my inquiry, especially because her Tamil identity appears to be central to Swarna’s own fascination with her and desire to perform the role of Manorani as the bereaved mother of an assassinated charismatic son. ‘Fascination’ and ‘desire’ are dynamic, complex, psychic energies, vital for all creative actors who take on ‘difficult’ roles, especially female ones, in theatre and film. Consider the generations of distinguished Western actors who have played roles, such Lady Macbeth (Shakespeare’s Macbeth) or Medea (Euripides’ Medea) who killed her children to avenge her husband for abandoning her or Clytemnestra (Aeschylus’ Oresteian Trilogy) who killed her husband Agamemnon to avenge his killing of their daughter Iphigenia in the Classical Greek tragedy. These are not characters one can like, but an actor who incarnates them must find something fascinating in them, to the point of obsession even, so as to inhabit them night after night in the theatre credibly, in all their capacity, as the case might be, for passion and profound violence.

Perhaps not incidentally, Manorani Sarvanamuttu did play the role of Clytemnestra at the British Council with Richard de Zoysa, her own son playing either the role of Aegisthus, her lover or her son Orestes who is duty bound, fated, to kill her because she killed his father the king. I saw this production of The Libation Bearers (the second play of the Trilogy), but can’t remember the exact year, perhaps 1988 nor the role Richard played but do remember Manorani’s powerfully statuesque presence, her poise and minimalist gestures, performed in an open corridor with high pillars, facing the audience seated on chairs arranged on a very English lawn modulated by a setting tropical sun. The texture of her voice was soft but strong, the timbre rich, I recall. She didn’t need to shout to project her voice, though it was an open-air show. She was an experienced amateur actor working with the playwright and director Lucien de Zoysa, who she married and had Richard with.

Modulating a Gift: A Female Actor’s Voice

But now that I have heard, while researching this piece, Manorani’s speaking voice (not her theatrical poetic voice as Clytemnestra the regicide) on a documentary film made after Richard’s death, I do think that hers was a singular ‘Ceylonese’ voice. That ‘Ceylon’ ceased existing once upon a time, except in memory, a memory popping up by chance on hearing a voice, that most fragile of memory traces with the power to make palpable, time lost.

Rukmani Devi is the only actor in the Lankan cinema of the early period who had a deep, textured, resonant voice with perfect pitch that perhaps reached the famous two octave range in singing, as Elvis Presley famously possessed. A star of the Hindi cinema once said that with that voice, had Rukmani Devi been an Indian she would have had quite a different career and that she did have an ‘operatic voice’, that is to say one with considerable power, range and texture which she was able to modulate to create feelings that we Lankans still respond to hearing her songs. The problem was that the dialogue written for her in the popular genre films was melodramatic in the extreme, formulaic, often laughable, and the delivery also similarly stilted. Her singing created and sustained the intensity of the films despite the slight lyrics. Radio, records and cassettes spread her voice and also Mohidin Baig’s, right across the country. She spoke an ‘accent-less’ Sinhala, without a trace of her Tamil mother tongue inflecting it.

The Aging Female Actor

It’s a fact well known that when female film-actors pass their youth, their roles diminish rapidly. But in striking contrast, male actors do go on acting until they are quite old and even have romantic scenarios written for them with young women old enough to be their granddaughters. Feminist film theorists have written about this stuff and brilliant leading female Hollywood stars have spoken out about this and taken productive action, on occasion, to rectify it. There simply are no film roles for female actors when they reach maturity of age, experience and technical skill, unlike in theatre, unless playing the role of an ‘aging actress’ of 50 refusing to accept career death so soon, as in All About Eve with Bette Davis.

Kadaima, the recent film Swarna performed in, directed by a surgeon on leave, Dr. Naomal Perera, was promoted as sequel to Vasantha Obeysekera’s classic Dadayama. Kadaima appears to have fizzled out trying a feeble pun on Dadayama with typical melodramatic plot contrivances of coincidences. But in Dadayama Swarna created an unforgettably powerful performance directly related, it should be emphasised, to Vasantha’s brilliant direction, script based on a notorious crime and complex editing of sound and image. Like Sumithra Peiris, Vasantha was also trained in filmmaking in France. After Dadayama’s success in 1983, the chance to perform a challenging role so late in her career, linked to yet another ‘true crime’, would have been an irresistible opportunity for Swarna as a mature and highly experienced award-winning actor.

An analysis of her style of performance follows, in relation to the Rani script and direction because they are integrally linked.

But at first, I want to create a historically informed, intellectual framework irrespective of whether I like the film or not. By ‘history,’ I mean Lankan film history, a history of film acting within the context of the history of political violence, especially the political terror of 1987-1990 and its aftermath during the civil war years. I do so because Rani has created what the Australian Cultural Studies scholar Meaghan Morris has theorised as ‘a Mass-Media Event’.

“An event is a complex interaction between commerce and ‘soul’; or, to speak more correctly, between film text, the institution of cinema and the unpredictable crowd-actions that endow mass-cultural events with their moment of legitimacy, and so modify mass-culture”.

The crowded discourse on Rani in the South is noteworthy, and appears to be unprecedented. This fact alone warrants a considered analysis beyond simply stating our individual likes and dislikes of the film, defending the film or criticising it. As a scholar working within the field of Cinema Studies, one is ethically bound to explore and analyse such ‘Media Events’ rationally and imaginatively, making clear one’s theoretical and other assumptions. In doing so, others may engage with the terms of my argument without being abusive. In such work, aesthetic and ethical values are not, in the final analysis, separable categories even as one is cognisant of the monetary value of films at this scale of production and the importance of box office revenue and the advertising machine that powers it. Often, in the history of cinema, these values have been in conflict with each other but as an ‘industrial art’, its very condition of possibility. I am drawn to filmmakers who burn so much time and energy to capture on film a few moments of intensity, intimate vitality that enriches life … all life, that propels us to think the unthinkable. This is why cinema matters, this is why the history of cinema has many, too many, martyrs. (To be continued)

by Laleen Jayamanne

Features

Towards a new international order: India, Sri Lanka and the new cold war

Will a peaceful and sustainable multipolar world be born when the rising economic weight of emerging economies is matched with rising geopolitical weight, as argued by renowned economist Jeffrey Sachs in his recent Other News article?

There is no question that, as the US-led world order collapses, a new multipolar world that can foster peace and sustainable development is urgently needed. BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) was established to promote the interests of emerging economies by challenging the economic institutions dominated by the West and the supremacy of the US dollar in international trade. Asia alone constitutes around 50% of the world’s GDP today. China is expected to become the world’s leading economy and India, the world’s third largest economy by 2030.

But does economic growth alone reflect improvement in the quality of life of the vast majority of people? And should it continue to be the central criteria for a “new international order”?

Unfortunately, BRICS appears to be replicating the same patterns of domination and subordination in its relations with smaller nations that characterize traditional imperial powers. Whether the world is unipolar or multipolar, the continuation of a dominant global economic and financial system based on competitive technological and capitalist growth and environmental, social and cultural destruction will fundamentally not change the world and the disastrous trajectory we are on.

Despite many progressives investing hope in the emerging multipolarity, there is a deep systemic bias that fails to recognise that the emerging economies are pursuing the same economic model as the West. This means we will continue to live in a world that prioritises unregulated transnational corporate growth and profit over environmental sustainability and social justice. China Communications Construction Company and the Adani Group are just two examples of controversial Chinese and Indian conglomerates reflecting this destructive continuity.

Is India, as Professor Sachs says, providing “skillful diplomacy” and “superb leadership” in international affairs? Look, for example, at India’s advancing vision of “Greater India,” Akhand Bharat (Undivided India) and behaviour towards its neighboring countries. Are these not strikingly similar to US strategies of hegemonic interference?

While India promotes its trade and infrastructure projects as enhancing regional security and welfare, experiences in Nepal demonstrate how Indian trade blockades and electricity grid integration with India have made Nepal dependent on and subordinate to India in meeting its basic energy and consumer needs. Similarly, Bangladesh’s electricity agreement with the Adani Group has created a situation allowing Adani to discontinue power supply to Bangladeshi consumers.

Since the fall of the Sheikh Hasina regime, there have been widespread demands to cancel the deal with Adani, which is seen as unequal and harmful to Bangladesh. Similarly, recent agreements made with Sri Lanka would expand India’s “energy colonialism” and overall political, economic and cultural dominance threatening Sri Lanka’s national security, sovereignty and identity.

During Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Sri Lanka, April 4-6, 2025, according to reports in the Indian media, some seven to ten agreements were signed to strengthen ties in defence, electricity grid interconnection, multi-product petroleum pipeline, digital transformation and pharmacopoeial practices between the two countries. The agreements have been signed using Sri Lankan Presidential power without debate or approval of the Sri Lankan Parliament. The secrecy surrounding the agreements is such that both the Sri Lankan public and media still do not know how many pacts were made, their full contents and whether the documents signed are legally binding agreements or simply “Memoranda of Understanding” (MOUs), which can be revoked.

The new five-year Indo-Lanka Defense Cooperation Agreement is meant to ensure that Sri Lankan territory will not be used in any manner that could threaten India’s national security interests and it formally guarantees that Sri Lanka does not allow any third power to use its soil against India. While India has framed the pact as part of its broader “Neighborhood First” policy and “Vision MAHASAGAR (Great Ocean)” to check the growing influence of China in the Indian Ocean region, it has raised much concern and debate in Sri Lanka.

As a member of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD)—a strategic alliance against Chinese expansion that includes the United States, Australia and Japan—India participates in extensive QUAD military exercises like the Malabar exercises in the Indian Ocean. In 2016, the United States designated India as a Major Defense Partner and in 2024, Senator Marco Rubio, current US Secretary of State, introduced a bill in the US Congress to grant India a status similar to NATO countries. In February 2025, during a visit to the USA by Modi, India and the US entered into a 10-year defence partnership to transfer technology, expand co-production of arms, and strengthen military interoperability.

Does this sound like the start of a new model of geopolitics and economics?

Sri Lankan analysts are also pointing out that with the signing of the defense agreement with India, “there is a very real danger of Sri Lanka being dragged into the Quad through the back door as a subordinate of India.” They point out that Sri Lanka could be made a victim in the US-led Indo-Pacific Strategy compromising its long-held non-aligned status and close relationship with China, a major investor, trade partner and supporter of Sri Lanka in international forums.

The USA and its QUAD partner India, as well as China and other powerful countries, want control over Sri Lanka, due to its strategic location in the maritime trade routes of the Indian Ocean. But Sri Lanka, which is not currently engaged in any conflict with an external actor, has no need to sign any defence agreements. The defence MOU with India represents further militarisation of the Indian Ocean as well as a violation of the 1971 UN Declaration of the Indian Ocean as a Zone of Peace and the principles of non-alignment—which both India and Sri Lanka have supported in the past.

Professor Sachs—who attended the Rising Bharat Conference, April 8-9, 2025 in New Delhi—has called for India to be given a seat as a permanent member in the UN Security Council gushing that “no other country mentioned as a candidate …comes close to India’s credentials for a seat.” But would this truly represent a move towards a “New International Order,” or would it simply be a mutation of the existing paradigm of domination and subordination and geopolitical weight being equated with economic weight, i.e., “might is right”?

Instead, the birth of a multipolar world requires the right of countries—especially small countries like India’s neighbours—to remain non-aligned amidst the worsening geopolitical polarisation of the new Cold War.

What we see today is not the emergence of a truly multipolar and just international order but continued imperialist expansion with local collaboration prioritising short-term profit and self-interest over collective welfare, leading to environmental and social destruction. Breaking free from this exploitative world order requires fundamentally reimagining global economic and social systems to uphold harmony and equality. It calls on people everywhere to stand up for their rights, speak up and uplift each other.

In this global transformation, India, China and the newly emergent economies have significant roles to play. As nations that have endured centuries of Western imperial domination, their mission should be to lead the global struggle for demilitarisation and the creation of an ecological and equitable human civilization rather than dragging smaller countries into a new Cold War.

by Dr. Asoka Bandarage

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoOrders under the provisions of the Prevention of Corruptions Act No. 9 of 2023 for concurrence of parliament

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRuGoesWild: Taking science into the wild — and into the hearts of Sri Lankans

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoPick My Pet wins Best Pet Boarding and Grooming Facilitator award

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoProf. Rambukwella passes away

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoSri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part IX

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoKing Donald and the executive presidency

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoACHE Honoured as best institute for American-standard education

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoThe Truth will set us free – I