Opinion

Sri Lankan democracy enters new phase of forced retreat

Text of the speech delivered by

Prof. Jayadeva Uyangoda

at the launch of the book,

Democracy and Democratization in Sri Lanka: Paths, Trends and imaginations, September 09, 2023, at Kamatha Cultural Center Auditorium, BMICH. Prof. Uyangoda is the Editor of this two-volume publication.

I have no doubt at all that the Chairperson of the BCIS, the Board of Academic Affairs, the BCIS management, the chapter contributors, and the BCIS staff are delighted to see the two volumes of Democracy and Democratization in Sri Lanka: Paths, Trends and imaginations in print. This, as far as I know, is the first major academic publication undertaken by the BCIS. It is Madam Chandrika Kumaratunga’s vision, initiative, guidance and unwavering support that has made this notable achievement possible.

It is she who proposed this research project’s thematic focus. She trusted the Academic Board and the research team and gave them a free hand to develop and work on it. At the same time, I apologize to her on behalf of the team for giving her a few anxious moments.

There were some delays caused partly by the general crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic. Besides, the missed deadlines set during normal times were unavoidable in a project of research and publication of this magnitude, carried out in a time of exceptional crises in our society, politics and the everyday life. For me as the lead researcher and the Editor, seeing these two volumes in print is a worthy reward for two and half years of hard labour.

Context

We at the BCIS began to conceptualize and plan this publication on the experience of democracy in our country, at a time when the Sri Lankan people were on the verge of losing their democratic heritage. When the year 2019 began, the threat of a hard authoritarian system replacing a weak and battered democratic order had indeed become alarmingly real.

We at the BCIS Board of Academic Affairs and its Chairperson felt that an analysis of why a promising democracy at the time of independence had failed so abysmally is a theme warranting critical scholarly inquiry and explanation.

Thus, we launched this research and publication project on democracy and democratization in Sri Lanka in mid -2020. As I have already mentioned, the Covid-19 Pandemic of 2021 came while we had just begun our work. It interfered with our project in a variety of ways, including halting most of the research.

More significantly, the Pandemic had led to a new political process in Sri Lanka. It can be termed as accelerated backsliding of democracy spearheaded by one faction of the ruling elites. It appeared almost like the last stage of Sri Lanka’s democracy.

But, Sri Lanka’s democracy, even in retreat, has shown that it has had some magical capacity for surprises. And that is exactly what we witnessed during the Spring and Summer of 2022. Sri Lankan citizens suddenly woke up demanding more democracy than what the political elites were willing to concede.

During the Aragalaya of 2022, the ordinary people, citizens without wealth or power, rose up demanding substantive democratic reforms. The ordinary citizens in their capacity as demos began to make claims to their ownership of democracy. They also highlighted that Sri Lanka’s democracy in general and representative democracy in particular, were in a deep crisis.

It was indeed an attempt by the people, demos, to re-generate as well as re-invent democracy in Sri Lanka. That is why the citizens’ protest in 2022 diserves to be acknowledged as a significant turning point in the somewhat twisted process of democratization in Sri Lanka.

In brief, the events of 2022 provided new perspectives and critical insights immensely useful to our own work on democracy and democratization in Sri Lanka. It showed us that the ordinary people play a powerful role as an agency for democratization. Their faith in democracy is far greater than that of the elites who exploit democracy for predatory ends. That is the spirit with which these two volumes evolved.

Organisation of the Book

The book has 22 chapters divided into two volumes. They are written by Sri Lankan scholars. The chapters are lined up under six themes which are as follows:

· Democracy in South Asia and Sri Lanka: Historical and Conceptual Contexts.

· Constitutional and Institutional Crises of Democracy in Sri Lanka.

· Democracy in the Social and Ethnic margins

· Alternative Forms of Democratic Thinking and Practice

· Democracy, Discontent and Resistance

· Protests as a Vector of Democratisation.

I want to share with you very briefly what I as the Editor see as unique about this book.

· This is the first book-length scholarly work exclusively devoted to the theme of democracy in Sri Lanka.

· All chapter contributors are Sri Lankan scholars who have been witnesses to the rise, decline and attempts at regeneration of democracy.

· The analysis developed in the chapters do not belong to a specific disciplinary area of the social sciences, such as political science or constitutional law. There is a plurality of approaches from the fields of social sciences and humanities.

· The book does not advocate or campaign for any particular version or variant of democracy. It argues for the plurality of democracy as a political concept and practice. Yet all chapter contributors stand for bringing the normative ethics of equality, freedom, justice and social emancipation back to the theory and practice of democracy.

Key Messages

What are the messages that these two volumes with chapters on diverse themes convey? Let me share with you a few of them that have a direct bearing on how we should view democracy and democratization anew.

· Democracy, as an organizing principle of political and social life, has strongly local social and popular roots in Sri Lanka as it has been the case elsewhere globally: It is a historical fact that modern democracy in Sri Lanka is an aspect of the European colonial legacy: However, people of Sri Lanka from various social classes have appropriated it and made use of it for their own social interests. In this process, there has been a double transformation. While the local society and its politics has been altered by liberal democracy, the local society has also changed the idea of democracy with a substantive, though subtle, critique of liberal democracy.

This has two theoretical implications. Firstly, the Sri Lankan people have not been passive recipients of a Western, European, or colonial, political idea. Secondly, they have played an active, agential role in appropriating and transforming that European idea. This book describes it as a creative process of ‘localizing democracy.’

· Ideas and practices of democracy have preceded the invention of the language of democracy

: Genealogies of the idea and practices of democracy predates its colonial origins in Sri Lanka and South Asia. The impulses and desires for democracy have always been there everywhere and whenever there were organized political power in the form of the state in pre-modern societies too. Historical and literary evidence in ancient and pre-colonial India and Sri Lanka show that the human desire for freedom from domination, independence, autonomy and justice have been integral to the social and political struggles within organized social formations.

It has been so in the processes of state formation in ancient Sri Lanka and South Asia, as elsewhere. This is the primary historical essence of ‘universalism’ of the idea of democracy. In other words, the idea and practices of democracy have been there in many forms in pre-colonial societies long before the language of modern democracy has been invented and the impulses for democracy rigidly formalized and frozen in meaning.

· The ordinary citizens are more faithful custodians of democracy than the elites:

Democratization is not a process confined to the activities of political elites as well as governments, as wrongly assumed in the mainstream democracy studies and assessments. The Sri Lankan case studies in the book show that democratization from below, at the level of the governed and the disempowered citizens, is most important in mapping paths of democratization in Sri Lanka. This thesis is valid to democracy’s liberal variant too.

The book shows that the dispossessed and the ordinary citizens, rather than the elites, have had a greater stake at defending and consolidating democracy. They have done it through the struggles of resistance against the elite-led de-democratization. The elites have domesticated, tamed, abandoned, and even became hostile to the liberal normative content of democracy.

People have also collaborated with backed the political elites in the latter’s projects of de-democratisation. However, in crucial moments of crisis the people, demos, have defended and deepened the idea and the normative content of even liberal democracy in Sri Lanka.

· Elite capture of liberal democracy has made democracy thin

: A lesson I have learned in the course of research for this book is that liberal democracy has the unintended consequence of dividing the population of Sri Lanka into two new classes in its own way: political elites and political non-elites. This has been a general pattern in other societies too.

Sri Lanka’s process of elite-led democratic backsliding has been paralleled with the introduction of representative government early last century. Elites who benefitted from the electoral, representative democracy have appropriated the liberal democracy and used it as an instrument for consolidating their social, economic, political and familial power.

Thus, the conception of democracy associated with Sri Lanka’s ruling elites has been a thin and truncated version of liberal democracy. Its role in democratization has now come to an effective end. Sri Lankan people await a strong democracy in terms of its social roots and normative commitments.

· Popular resistance to deprivations and unjust exercise of power has deepened the normative foundations of democracy in Sri Lanka

: The instrumentalist use of representative and parliamentary democracy by the elites is only one side of the story of democratization in Sri Lanka. In contrast, there is a subaltern story of democratization too.

The Left parties, working class, peasants, the working people, women’s groups, ethnic minorities, and student movements have contributed substantively to deepening the idea, the meaning, normative goals and the social relevance of Sri Lanka’s democracy. Through social practices of demands and direct political action for substantive equality and justice, they have shown how the limits of narrowly conceived and much abused representative democracy could be reformed. Thus, Sri Lanka’s democracy is not the monopolistic possession of the political elites. It is the inheritance of a plurality of non-elite social groups as well.

· Continuing conflict between democratic backsliding and popular demand for more democracy awaits a deep-democratic resolution:

Since independence, Sri Lanka’s democracy has evolved along two contradictory trajectories. The first is the path of democratic backsliding and de-democratization chosen by the elites. The second is the path of demanding and fighting for more democracy by the subordinate and non-elite social classes, trade unions and social movements, the civil society groups, and reformist elites.

The conflict between these two opposing paths is a major facet of the crisis of democratization in Sri Lanka. Its resolution presupposes a project of re-democratisation through radically substantive political and constitutional reforms.

What is Happening to Democracy

Let us briefly reflect on what is happening to democracy in Sri Lanka at present. Sri Lankan democracy seems to have entered a new phase of forced retreat engineered by the new ruling coalition. People of Sri Lanka who have yearend for the revival of democracy find themselves caught up in a new version of what our book calls the ‘de-democratization trap.

’ Its key feature has been the incorporation of ordinary citizens as disempowered voters to a deceitful social contract crafted by the political elites. As the citizen’s protests last year and this year have shown us, that deceitful social contract is now shattered. Citizens want to replace it with a deeply democratic and authentic social contract.

Meanwhile, there seems to be two processes of polarization of the Sri Lankan society into two hostile camps. The first is between the haves and have nots in the economic and social sense. The second is the growing enmity between the majority of the citizens who crave for more democracy and a minority of the elites who thrive on no democracy. The ways in which these polarities and contradictions will play themselves out are sure to shape the nature of politics of Sri Lanka in the months and years to come.

Returning to open democracy, more executive, legislative and judicial accountability, re-democratization of the constitution, the state, the government, and parliament, guaranteeing of economic and social justice to the poor, the working people and the middle classes are essential pre-conditions for resolving these contradictions peacefully with no recourse to violence by any side. That is also a message implicit in our book.

So, students of democracy in Sri Lanka will have a politically exciting time ahead. I and my collaborators sincerely hope that these two volumes will inspire a new interest in democracy studies among the young scholars in Sri Lanka. I am also hopeful that the readers will not fail to notice that the chapters have been written by a team of Sri Lankan scholars who have a deep passion for democracy.

Finally, let me thank a few people whose contribution to the success of this initiative warrants special acknowledgement. I have already referred to the inspiring and non-interventionist leadership provided by Madam Kumaratunga. Of course, it is our team of chapter contributors who have made these two volumes actually possible. They had the patience to tolerate the constant nagging by an impatient Editor and his support staff.

I must also mention the contribution made by our two copy-editors, Madara Rammunthugala and Nicola Perera, for refining the entire text. All reveiwers of the draft chapters also deserve my grateful acknowledgement for their contribution to ensuring the scholarly quality and standards of the publication. Suresh Amuhena designed the cover for us amidst many other commitments. Dr. Minna Taheer and Ms. Isuri Wickramaratna of the BCIS extended to me their assiatance throughout this project.

The BCIS staff Board of Academic Affairs and BMICH Board of Management ensured generous institutional support for the success of this entire intiative. Finally, Mr. Vijitha Yapa and his staff undertook the task of designing, printing and selling the book. All of them are partners of this worthy achievement. There are so many others who deserve my sincere thanks, and they are mentioned by name in the ‘Acknowledgements’ section book.

Finally, I am really happy that we have Professor Pratap Bhanu Mehta, an eminent scholar from India, as our keynote speaker. I will not take any more of your time to allow you to listen to his erudite presentation.

Opinion

Buddhist insights into the extended mind thesis – Some observations

It is both an honour and a pleasure to address you on this occasion as we gather to celebrate International Philosophy Day. Established by UNESCO and supported by the United Nations, this day serves as a global reminder that philosophy is not merely an academic discipline confined to universities or scholarly journals. It is, rather, a critical human practice—one that enables societies to reflect upon themselves, to question inherited assumptions, and to navigate periods of intellectual, technological, and moral transformation.

In moments of rapid change, philosophy performs a particularly vital role. It slows us down. It invites us to ask not only how things work, but what they mean, why they matter, and how we ought to live. I therefore wish to begin by expressing my appreciation to UNESCO, the United Nations, and the organisers of this year’s programme for sustaining this tradition and for selecting a theme that invites sustained reflection on mind, consciousness, and human agency.

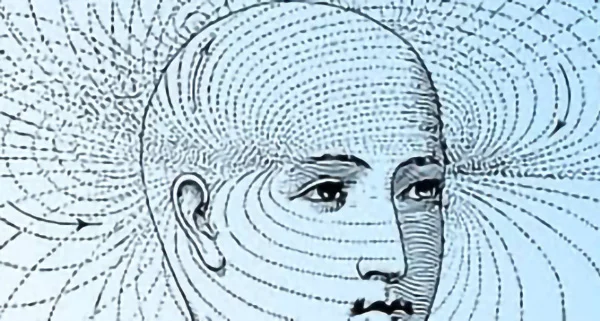

We inhabit a world increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence, neuroscience, cognitive science, and digital technologies. These developments are not neutral. They reshape how we think, how we communicate, how we remember, and even how we imagine ourselves. As machines simulate cognitive functions once thought uniquely human, we are compelled to ask foundational philosophical questions anew:

What is the mind? Where does thinking occur? Is cognition something enclosed within the brain, or does it arise through our bodily engagement with the world? And what does it mean to be an ethical and responsible agent in a technologically extended environment?

Sri Lanka’s Philosophical Inheritance

On a day such as this, it is especially appropriate to recall that Sri Lanka possesses a long and distinguished tradition of philosophical reflection. From early Buddhist scholasticism to modern comparative philosophy, Sri Lankan thinkers have consistently engaged questions concerning knowledge, consciousness, suffering, agency, and liberation.

Within this modern intellectual history, the University of Peradeniya occupies a unique place. It has served as a centre where Buddhist philosophy, Western thought, psychology, and logic have met in creative dialogue. Scholars such as T. R. V. Murti, K. N. Jayatilleke, Padmasiri de Silva, R. D. Gunaratne, and Sarathchandra did not merely interpret Buddhist texts; they brought them into conversation with global philosophy, thereby enriching both traditions.

It is within this intellectual lineage—and with deep respect for it—that I offer the reflections that follow.

Setting the Philosophical Problem

My topic today is “Embodied Cognition and Viññāṇasota: Buddhist Insights on the Extended Mind Thesis – Some Observations.” This is not a purely historical inquiry. It is an attempt to bring Buddhist philosophy into dialogue with some of the most pressing debates in contemporary philosophy of mind and cognitive science.

At the centre of these debates lies a deceptively simple question: Where is the mind?

For much of modern philosophy, the dominant answer was clear: the mind resides inside the head. Thinking was understood as an internal process, private and hidden, occurring within the boundaries of the skull. The body was often treated as a mere vessel, and the world as an external stage upon which cognition operated.

However, this picture has increasingly come under pressure.

The Extended Mind Thesis and the 4E Turn

One of the most influential challenges to this internalist model is the Extended Mind Thesis, proposed by Andy Clark and David Chalmers. Their argument is provocative but deceptively simple: if an external tool performs the same functional role as a cognitive process inside the brain, then it should be considered part of the mind itself.

From this insight emerges the now well-known 4E framework, according to which cognition is:

Embodied – shaped by the structure and capacities of the body

Embedded – situated within physical, social, and cultural environments

Enactive – constituted through action and interaction

Extended – distributed across tools, artefacts, and practices

This framework invites us to rethink the mind not as a thing, but as an activity—something we do, rather than something we have.

Earlier Western Challenges to Internalism

It is important to note that this critique of the “mind in the head” model did not begin with cognitive science. It has deep philosophical roots.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

famously warned philosophers against imagining thought as something occurring in a hidden inner space. Such metaphors, he suggested, mystify rather than clarify our understanding of mind.

Similarly, Franz Brentano’s notion of intentionality—his claim that all mental states are about something—shifted attention away from inner substances toward relational processes. This insight shaped Husserl’s phenomenology, where consciousness is always world-directed, and Freud’s psychoanalysis, where mental life is dynamic, conflicted, and socially embedded.

Together, these thinkers prepared the conceptual ground for a more process-oriented, relational understanding of mind.

Varela and the Enactive Turn

A decisive moment in this shift came with Francisco J. Varela, whose work on enactivism challenged computational models of mind. For Varela, cognition is not the passive representation of a pre-given world, but the active bringing forth of meaning through embodied engagement.

Cognition, on this view, arises from the dynamic coupling of organism and environment. Importantly, Varela explicitly acknowledged his intellectual debt to Buddhist philosophy, particularly its insights into impermanence, non-self, and dependent origination.

Buddhist Philosophy and the Minding Process

Buddhist thought offers a remarkably sophisticated account of mind—one that is non-substantialist, relational, and processual. Across its diverse traditions, we find a consistent emphasis on mind as dependently arisen, embodied through the six sense bases, and shaped by intention and contact.

Crucially, Buddhism does not speak of a static “mind-entity”. Instead, it employs metaphors of streams, flows, and continuities, suggesting a dynamic process unfolding in relation to conditions.

Key Buddhist Concepts for Contemporary Dialogue

Let me now highlight several Buddhist concepts that are particularly relevant to contemporary discussions of embodied and extended cognition.

The notion of prapañca, as elaborated by Bhikkhu Ñāṇananda, captures the mind’s tendency toward conceptual proliferation. Through naming, interpretation, and narrative construction, the mind extends itself, creating entire experiential worlds. This is not merely a linguistic process; it is an existential one.

The Abhidhamma concept of viññāṇasota, the stream of consciousness, rejects the idea of an inner mental core. Consciousness arises and ceases moment by moment, dependent on conditions—much like a river that has no fixed identity apart from its flow.

The Yogācāra doctrine of ālayaviññāṇa adds a further dimension, recognising deep-seated dispositions, habits, and affective tendencies accumulated through experience. This anticipates modern discussions of implicit cognition, embodied memory, and learned behaviour.

Finally, the Buddhist distinction between mindful and unmindful cognition reveals a layered model of mental life—one that resonates strongly with contemporary dual-process theories.

A Buddhist Cognitive Ecology

Taken together, these insights point toward a Buddhist cognitive ecology in which mind is not an inner object but a relational activity unfolding across body, world, history, and practice.

As the Buddha famously observed, “In this fathom-long body, with its perceptions and thoughts, I declare there is the world.” This is perhaps one of the earliest and most profound articulations of an embodied, enacted, and extended conception of mind.

Conclusion

The Extended Mind Thesis challenges the idea that the mind is confined within the skull. Buddhist philosophy goes further. It invites us to reconsider whether the mind was ever “inside” to begin with.

In an age shaped by artificial intelligence, cognitive technologies, and digital environments, this question is not merely theoretical. It is ethically urgent. How we understand mind shapes how we design technologies, structure societies, and conceive human responsibility.

Buddhist philosophy offers not only conceptual clarity but also ethical guidance—reminding us that cognition is inseparable from suffering, intention, and liberation.

Dr. Charitha Herath is a former Member of Parliament of Sri Lanka (2020–2024) and an academic philosopher. Prior to entering Parliament, he served as Professor (Chair) of Philosophy at the University of Peradeniya. He was Chairman of the Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE) from 2020 to 2022, playing a key role in parliamentary oversight of public finance and state institutions. Dr. Herath previously served as Secretary to the Ministry of Mass Media and Information (2013–2015) and is the Founder and Chair of Nexus Research Group, a platform for interdisciplinary research, policy dialogue, and public intellectual engagement.

He holds a BA from the University of Peradeniya (Sri Lanka), MA degrees from Sichuan University (China) and Ohio University (USA), and a PhD from the University of Kelaniya (Sri Lanka).

(This article has been adapted from the keynote address delivered

by Dr. Charitha Herath

at the International Philosophy Day Conference at the University of Peradeniya.)

Opinion

We do not want to be press-ganged

Reference ,the Indian High Commissioner’s recent comments ( The Island, 9th Jan. ) on strong India-Sri Lanka relationship and the assistance granted on recovering from the financial collapse of Sri Lanka and yet again for cyclone recovery., Sri Lankans should express their thanks to India for standing up as a friendly neighbour.

On the Defence Cooperation agreement, the Indian High Commissioner’s assertion was that there was nothing beyond that which had been included in the text. But, dear High Commissioner, we Sri Lankans have burnt our fingers when we signed agreements with the European nations who invaded our country; they took our leaders around the Mulberry bush and made our nation pay a very high price by controlling our destiny for hundreds of years. When the Opposition parties in the Parliament requested the Sri Lankan government to reveal the contents of the Defence agreements signed with India as per the prevalent common practice, the government’s strange response was that India did not want them disclosed.

Even the terms of the one-sided infamous Indo-Sri Lanka agreement, signed in 1987, were disclosed to the public.

Mr. High Commissioner, we are not satisfied with your reply as we are weak, economically, and unable to clearly understand your “India’s Neighbourhood First and Mahasagar policies” . We need the details of the defence agreements signed with our government, early.

RANJITH SOYSA

Opinion

When will we learn?

At every election—general or presidential—we do not truly vote, we simply outvote. We push out the incumbent and bring in another, whether recycled from the past or presented as “fresh.” The last time, we chose a newcomer who had spent years criticising others, conveniently ignoring the centuries of damage they inflicted during successive governments. Only now do we realise that governing is far more difficult than criticising.

There is a saying: “Even with elephants, you cannot bring back the wisdom that has passed.” But are we learning? Among our legislators, there have been individuals accused of murder, fraud, and countless illegal acts. True, the courts did not punish them—but are we so blind as to remain naive in the face of such allegations? These fraudsters and criminals, and any sane citizen living in this decade, cannot deny those realities.

Meanwhile, many of our compatriots abroad, living comfortably with their families, ignore these past crimes with blind devotion and campaign for different parties. For most of us, the wish during an election is not the welfare of the country, but simply to send our personal favourite to the council. The clearest example was the election of a teledrama actress—someone who did not even understand the Constitution—over experienced and honest politicians.

It is time to stop this bogus hero worship. Vote not for personalities, but for the country. Vote for integrity, for competence, and for the future we deserve.

Deshapriya Rajapaksha

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

News3 days ago

News3 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoNational Communication Programme for Child Health Promotion (SBCC) has been launched. – PM

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II