Features

Some personal insights and a broad brush canvas of Ena de Silva

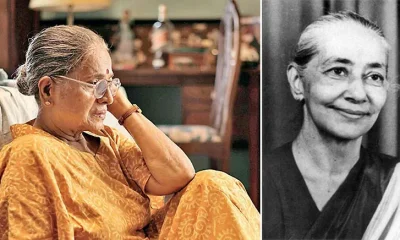

Ena de Silva’s 100th birth centenary fell on

Excerpted from

Exploring with Ena by Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha

Towards the end of 2019 I spent a couple of days at Aluwihare, where I had had many happy times with my aunt Ena de Silva. Since her death in 2015 1 tried to get there twice or thrice a year, not just for sentiment, but also to provide company for Piyadasa and Suja who have lived and worked there for many years.

The Matale Heritage Centre Ena established, for batik and embroidery, still continues on the premises, but the girls – some who started work there over 50 years ago – go home in the evenings and Piyadasa and Suja are left alone. Family members sometimes visit and occasionally stay overnight, but this does not happen often. And Piyadasa and Suja relish company and appreciate the fact that I now go up there to stay more than anyone else. So too Ena loved my frequent visits in the last years of her life. Ena’s daughter Kusum, who lives in California, thanks me but gratitude is unnecessary, for it is always a pleasure to be there, though one still sadly misses its chatelaine.

Piyadasa started at Alu in 1976, looking after Ena’s father, Sir Richard Aluwihare, and then took care of the house himself for around five years after he died in December that year. He then served Ena who went to live there in 1981, two years after her husband Osmund de Silva died. She had not wanted to continue in the home they had lived in for over 20 years and went off to the Virgin Islands as a Consultant, to adjust, shortly after she was widowed. When she came back, she moved to Alu and lived there for 34 years.

Suja came to cook for her in 1983, not able even to boil a pot of water in those days, according to Ena. But she turned into a marvelous cook, carrying out Ena’s wonderful ideas for the most delicious concoctions, ranging from polos sandwiches to Alu chicken, with a sauce combining sugar and spice and all things nice, as indeed the sandwiches did. And, though Ena claimed she had no expertise in puddings, Suja did well with Humbug, a pudding I was served when I first went there in 1993, and had often since though it always tasted different.

In 1983 went there with Nigel Hatch, whom Ena’s driver of those days, Sena, thought he recognized as the nephew when he was sent to pick us up at the bus stand. Nigel did look a bit like my Uncle Lakshman who had visited Ena two or three times after she moved there, coming up from Kurunagala where he was Bishop on his rounds of inspection of the clergy in his diocese. I think Sena saw him just the once, for he died in 1983 but, tall and handsome as he was, he had obviously made an impression.

On my visit in 2019 Nigel joined me on the second day, coming up on the early train from Colombo and then getting a bus from Kandy. That afternoon, after the statutory snooze after Suja’s wonderful lunch, we went up to the rock for tea which Piyadasa brought up on a tray, carefully negotiating the now slippery steps after the incessant rain of the last few weeks.

The rock was a natural feature which Ena had had cemented in 1989, so that the poruwa ceremony for her daughter’s wedding could take place high above the garden in front of the house, above too the upper terrace to which steps led from the garden . Bells had been strung up on the edge of the rock, to ring when the wind blew, and the sound would come to us for the next 25 years before the last bell fell away, shortly before Ena died.

And then, before it got dark, following Ena’s advice that we always be careful about what she described as creepy-crawlies, we went along that cliffside to the graves at the other edge, a little enclosure with inscribed stones for her parents over the vault where her ashes lie with theirs. Behind are inscriptions for her husband and her sister and brother-in-law and her son, though the ashes of the first are not there for they were scattered at the confluence of river and sea at Mutwal as he wished.

In the evening we sat out on the terrace over beer, and Suja’s vegetable patties, before going in for an Alu chicken feast. It was then that my driver Kithsiri, who had grown devoted to Ena in the 22 years he knew her, suggested we drive next day to Wireless Kanda. That was what she called Riverstone, the highest peak in the hills opposite, which we had often driven to in the eighties since Ena was always keen to go loafing.

So next morning, after breakfast, we set out, climbing through Rattota to the steep slopes beyond. With Ena it had initially been an afternoon drive, leaving early though so that we could get back before the descent of the mists that swirled round the hill at tea-time. And now, though it was morning, we had a sense of what we had experienced before, as rain started dripping down when we approached the peak.

But there was a big difference, in that 30 years before we had been the only people heading that way. Now, even on this rainy morning, there were crowds. It was obviously a popular place for a Poya day excursion, and at the turn-off to the peak there were heaps of cars and loud music.

Still, the drive brought back many happy memories. And it was on the way back that I thought that perhaps I would go through my diaries and set out the various journeys Ena and I had been on, starting with the excursion Ena had suddenly proposed to Nigel and me when, as she later put it, she had assessed us over lunch, way back in 1983, and decided that we were game to go loafing.

In doing this I am making use of what I wrote for The Moonemalle Inheritance, the book I produced for her 90th birthday in 2012. The second part of that book recorded travels with her over the preceding 30 years. Some of this is reproduced here but I have added so as to make clear what great friends we were, and the enormous fun we had together, not only travelling but sitting together and talking, at Aluwihare and elsewhere.

Some of this will read like a catalogue, but I wanted to record all our times together at Aluwihare, and much more that we did together. And I will try too to make clear the impact of her work, and how much she contributed to arts and crafts in this country.

It was only in 1983 that I got to know her properly. Having heard about my adventures at S.Thomas’, she decided that there was another unorthodox person in the family and invited me to stay with her at Aluwihare. It was 18 months after she had gone there at the end of 1981 that I made, in May 1983, the first of what were to be frequent visits to her.

Ena was not an especially close relation. Her mother Lucille was a Moonemalle, whose father’s sister was the mother of my maternal grandmother, Esme Goonewardene. But the two cousins, Esme and Lucille, both born in the last year of the 19th century, remained close, perhaps because they both married Civil Servants who were senior administrators in the last years of British rule.

My grandfather Cyril Wickremesinghe however died young and could make no contribution to independent Ceylon. Sir Richard Aluwihare, who had been five years younger, survived into the late seventies. He had retired in 1955 and moved to the new house which he had built on top of a hill in Aluwihare village, looking eastward towards the Gammmaduwa Hills. But a year later he was drawn into politics, contesting the Anuradhapura seat where he had served as Government Agent after my grandfather.

One of their predecessors had been a Britisher called Freeman who had won election to the Legislative Council on the strength of his service to the area. But there was no such gratitude in 1956 and Sir Richard was roundly defeated in the sweeping victory of S W R D Bandaranaike’s MEP colaition. Also defeated, in the Matale constituency in which Aluwihare lay, was Sir Richard’s brother Bernard who had crossed back to the UNP. In 1951, when Bandaranaike left the UNP government to form the SLFP, he had been one of his few aristocratic supporters.

His departure in 1956 was unfortunate, for had he stayed he would undoubtedly have been Bandaranaike’s deputy, and succeeded him as Prime Minister when he was assassinated in 1959. As it was, the Deputy belonged to a caste which others in the party considered unsuitable. That led to vast intrigues, an interim Prime Minister who was a disaster, a hung Parliament in March 1960 so that the UNP Prime Minister (Bernard was his deputy in that Cabinet) dissolved Parliament when he was defeated on the throne speech, and the emergence of Mrs Bandaranaike as leader of the Socialist United Party and Prime Minister after the July 1960 election.

Meanwhile Bandaranaike had offered Sir Richard the position of High Commissioner to India, and he served in New Delhi from 1957 onward. Lucille however died there early in 1961 and, though he soldiered on, he was not really in control and his daughters persuaded him to give up and return home. So in 1963 he went back to live at Aluwihare. When he died, in December 1976, his daughters found he had left it to them to divide up his property as they wished. Phyllis, whose husband Pat was a Ratwatte, at the top of the Kandyan aristocratic tree, took the properties in Kandy while Ena got Aluwihare. To everyone’s surprise she decided to retire there herself after her husband Osmund de Silva died, a couple of years after her father.

Osmund had succeeded Sir Richard as Inspector General of Police though, as Ena told the Queen, who expressed some surprise when introduced to the father and son-in-law as the head and deputy head of the police, that that was his profession. Sir Richard was a Civil Servant who had been brought in when the first Prime Minister of independent Ceylon decided that the British head of police had to be replaced. Ceylonese officers were not however senior enough to take over so Ossie, as the most senior of them, had to wait until his father-in-law retired before heading the force.

Ena had run away from Ladies College to marry Ossie. He was from a different caste and her parents, who had found him excellent company as a police officer when they served in distant districts, were not comfortable at the idea of him marrying into the family. There was a court case at which, Ena said my grandparents were been summoned as witnesses. The judge hit on the healthy compromise of asking a British priest to keep Ena until she was old enough to decide on her own if she wanted to get married. At the age she was when she ran away, she required parental consent.

To her surprise she found that the priest expressed himself entirely on her side, when she was sent to his house, but told her she needed to be patient. She managed to achieve this, and duly married when she could, and a couple of years later was reconciled with her parents after her first child was born. Still, she continued to have a reputation for being unorthodox, and she lived up to this when, after her husband retired she abandoned social life altogether and instead concentrated on what became Ena de Silva fabrics.

Ossle’s retirement had been premature. When he was appointed, the then Prime Minister Sir John Kotelawala had offered him a contract, and when this expired Bandaranaike did not renew it. Ena claimed that Ossie had made it clear to him that his allegiance was to the law and not the government. He was not helped by his colleagues, all angling for the post, though Bandaranaike characteristically trumped them all by appointing his bridge partner Abeykoon, another senior public servant, as IGP. Sadly several of the senior police officials then entered into political intriguing, culminating in the 1962 coup attempt.

There had been attempts to inveigle Ossie too into joining, and Ena would frequently cite his brusque response to Aelian Kannangara, a UNP stalwart who had been part of the conspiracy. Ossie had told him, ‘We are not the Praetorian Guard’, a line Ena relished. She also noted that he had firmly rejected Bandaranaike’s apologetic offers of other positions, embassies as well as the Chairmanship of Air Ceylon. Interestingly she claimed that the only relation on her side who appreciated Ossie’s position was her mother Lucille, who had been most opposed to the marriage, but who was a Moonemalle with rigid standards of public conduct.

Osmund de Silva died a little over two years after Sir Richard. Ena was devastated, and needed to get away. Friends, notably Tilak Gooneratne she would later say, who had also married into an old Civil Service family and been a respected Civil Servant himself before going to the Commonwealth Secretariat in London and then becoming our High Commissioner there, arranged for a Commonwealth Consultancy. Ena thus worked for a year and a half in the British Virgin Islands. She handed over the business to Ossie’s nephew Keerthi Wickramasuriya, who was married to Thea Schokman whom I had known as the Librarian of the British Council in Kandy during my schooldays. But they soon afterwards went through an acrimonious divorce which also devastated the business.

Fortunately Geoffrey Bawa, the architect who had developed a remarkable collaboration with her after he designed a house for her in Colombo, had rented that house as an office for the many projects he undertook for the new government of J R Jayewardene, most memorably the new Parliament but also Ruhuna University. So that iconic house at least remained safe.

When Ena came back, she retired to Aluwihare. She had set up there a Batik workshop, one amongst many that fed the flourishing business of Ena de Silva Fabrics which she had started after her husband’s retirement from the police. Though she was unable to resurrect the whole business, she decided to do what she could for the Aluwihare Centre which had provided gainful employment over the years to the villagers, including several relations.

Over the next thirty years the Matale Heritage Centre, as I first suggested it be called, developed not only fabrics, with traditional embroidery added onto its trademark batiks, but also a carpentry workshop and a brass foundry. These were started when Ena decided that the young men of the village also needed work, else they would get into mischief. The claim was prophetic, for the young men of Aluwihare escaped the fate of many others in the country when the JVP insurrection of the late eighties took its toll.

The workshops were followed by a Restaurant, or rather two, when Ena decided she should do something the middle aged women of the village too. They were known as Alu Kitchens. She had begun by supplying meals on order in a custom built kitchen on her own premises, designed with fantastic views by Anjalendran, Bawa’s best apprentice. This was K1 (kitchen one) and then, deciding she had to expand into the village too, she set up K2 as a small guest house in a property by the road that belonged to the family of her cousin Alick. He it was who had succeeded Bernard as the UNP candidate for the area, lucky in that, when Bernard died suddenly, his son had been too young to take over. The UNP, anxious for any Aluwihare, had found Alick, the youngest son of Bernard’s step-brother Willie, the most suitable of those willing, though he had nothing like the educational or intellectual qualifications of Bernard or Sir Richard. But he proved an active constituency MP and in turn established his own dynasty.

Ena herself steered clear of politics. Though the family was strongly committed to the UNP and indeed Chari, the oldest son of her sister Phyllis, had been active in the 1977 election campaign and occupied increasingly important administrative roles in successive UNP governments, she was strongly critical of J R Jayewardene and his behavior. I suspect one reason we got on so well was my forthright opposition to Jayewardene when this was not at all popular in Colombo circles. In fact she proved even more deeply critical of his legacy, suggesting when I finally decided to vote for the UNP, in the General election of 2001, in the belief that its leadership had reformed and would do better, that she was not quite so optimistic.

Though she claimed to know nothing of politics, she was an extraordinarily sharp observer of political developments, both in Sri Lanka and abroad. She had a few strong prejudices, but these often tallied with my own. The few things we differed on included both President Premadasa and, ironically given Premadasa’s own dislike of India, the role of India in Sri Lankan politics. I was myself a late convert to Premadasa, having come to appreciate his obvious devotion to rural development, as well as his very healthy approach to the rights and the welfare of the minorities. But Ena thought he had ridden roughshod over too many and, though she granted he was a better leader than either his predecessor or his successor, that did not make him acceptable.

Ena’s attitude to D B Wijetunge I think summed up her very practical if idiosyncratic view of politics. She claimed that she was never so frightened for the country as when he was President, because he was so clearly an idiot. That very healthy and no-nonsense approach was in marked contrast to the absurd panegyrics about the man by the old elite, which had resented Premadasa’s ascendancy, and it confirmed my view that an ounce of Ena’s prejudices was worth a ton of anyone else’s analysis.

About India she was less rational. Though she was quite critical about what she saw as the extreme Sinhala Buddhist prejudices of her husband, she had certainly absorbed something of his views in her hostility to the Indian Tamil presence in the hills which she claimed had been at the cost of the Sinhala peasantry. This was certainly correct, and we agreed in noting the responsibility of the British in having so altered the demography of the country, but she thought I was too indulgent in claiming that much more had to be done for them once they had been granted citizenship, and also that depriving them of citizenship in the forties had been unjust.

She was also convinced that the efforts of Tamil politicians to obtain greater autonomy were excessive, and we had to agree to disagree about devolution. But her essential fairness never left her, and she quite understood the enormity of what the Jayewardene government had done in 1981 and 1983 in unleashing violence on Tamils, and how this made Tamil demands for greater control of the areas in which they lived more understandable. But she continued to believe that India had stirred the pot out of pure self interest, and that Indian efforts to broker peace were not to be trusted.

Such criticism trumped even her awareness that the Jayewardene government had engaged in unnecessary confrontation with India in its effort to align itself with the West in the Cold War. For, interestingly given her elite upbringing during the colonial period, Ena had an even stronger distrust of the West and its efforts to control other countries. She had no illusions whatsoever about its self-serving agenda, and this made her a strong ally in recent years when, once again, the urban elite supported Western efforts to derail our struggle against terrorism. I was glad then that I was able to convince her that India had played a positive role in this regard, though I believe she continued to wonder what benefits India expected to derive from its support.

Features

Voting for new Pope set to begin with cardinals entering secret conclave

On Wednesday evening, under the domed ceiling of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, 133 cardinals will vote to elect the Catholic Church’s 267th pope.

The day will begin at 10:00 (09:00 BST) with a mass in St Peter’s Basilica. The service, which will be televised, will be presided over by Giovanni Battista Re, the 91-year-old Cardinal Dean who was also the celebrant of Pope Francis’ funeral.

In the early afternoon, mobile signal within the territory of the Vatican will be deactivated to prevent anyone taking part in the conclave from contacting the outside world.

Around 16:15 (15:15 BST), the 133 cardinal electors will gather in the Pauline Chapel and form a procession to the Sistine Chapel.

Once in the Sistine Chapel, one hand resting on a copy of the Gospel, the cardinals will pronounce the prescribed oath of secrecy which precludes them from ever sharing details about how the new Pope was elected.

When the last of the electors has taken the oath, a meditation will be held. Then, the Master of Pontifical Liturgical Celebrations Diego Ravelli will announce “extra omnes” (“everybody out”).

He is one of three ecclesiastical staff allowed to stay in the Sistine Chapel despite not being a cardinal elector, even though they will have to leave the premises during the counting of the votes.

The moment “extra omnes” is pronounced marks the start of the cardinals’ isolation – and the start of the conclave.

The word, which comes from the Latin for “cum clave”, or “locked with key” is slightly misleading, as the cardinals are no longer locked inside; rather, on Tuesday Vatican officials closed the entrances to the Apostolic Palace – which includes the Sistine Chapel- with lead seals which will remain until the end of the proceedings. Swiss guards will also flank all the entrances to the chapel.

Diego Ravelli will distribute ballot papers, and the cardinals will proceed to the first vote soon after.

While nothing forbids the Pope from being elected with the first vote, it has not happened in centuries. Still, that first ballot is very important, says Austen Ivereigh, a Catholic writer and commentator.

“The cardinals who have more than 20 votes will be taken into consideration. In the first ballot the votes will be very scattered and the electors know they have to concentrate on the ones that have numbers,” says Ivereigh.

He adds that every other ballot thereafter will indicate which of the cardinals have the momentum. “It’s almost like a political campaign… but it’s not really a competition; it’s an effort by the body to find consensus.”

If the vote doesn’t yield the two-third majority needed to elect the new pope, the cardinals go back to guesthouse Casa Santa Marta for dinner. It is then, on the sidelines of the voting process, that important conversations among the cardinals take place and consensus begins to coalesce around different names.

According to Italian media, the menu options consist of light dishes which are usually served to guests of the residence, and includes wine – but no spirits. The waiters and kitchen staff are also sworn to secrecy and cannot leave the grounds for the duration of the conclave.

From Thursday morning, cardinals will be taking breakfast between 06:30 (05:30 BST) and 07:30 (06:30 BST) ahead of mass at 08:15 (07:15 BST). Two votes then take place in the morning, followed by lunch and rest. In his memoirs, Pope Francis said that was when he began to receive signals from the other cardinals that serious consensus was beginning to form around him; he was elected during the first afternoon vote. The last two conclaves have all concluded by the end of the second day.

There is no way of knowing at this stage whether this will be a long or a short conclave – but cardinals are aware that dragging the proceedings on could be interpreted as a sign of gaping disagreements.

As they discuss, pray and vote, outside the boarded-up windows of the Sistine Chapel thousands of faithful will be looking up to the chimney to the right of St Peter’s Basilica, waiting for the white plume of smoke to signal that the next pope has been elected.

[BBC]

Features

Beyond Left and Right: From Populism to Pragmatism and Recalibrating Democracy

The world is going through a political shake-up. Everywhere you look—from Western democracies to South Asian nations—people are choosing leaders and parties that seem to clash in ideology. One moment, a country swings left, voting for progressive policies and climate action. The next, a neighbouring country rushes into the arms of right-wing populism, talking about nationalism and tradition.

It’s not just puzzling—it’s historic. This global tug of war between opposing political ideas is unlike anything we’ve seen in recent decades. In this piece, I explore this wave of political contradictions, from the rise of labour movements in Australia and Canada, to the continued strength of conservative politics in the US and India, and finally to the surprising emergence of a radical leftist party in Sri Lanka.

Australia and Canada: A Comeback for Progressive Politics

Australia recently voted in the Labour Party, with Anthony Albanese becoming Prime Minister after years of conservative rule under Scott Morrison. Albanese brought with him promises of fairer wages, better healthcare, real action on climate change, and closing the inequality gap. For many Australians, it was a fresh start—a turn away from business-as usual politics.

In Canada, a political shift is unfolding with the rise of The Right Honourable Mark Carney, who became Prime Minister in March 2025, after leading the Liberal Party. Meanwhile, Jagmeet Singh and the New Democratic Party (NDP) are gaining traction with their progressive agenda, advocating for enhanced social safety nets in healthcare and housing to address growing frustrations with rising living costs and a strained healthcare system..

But let’s be clear—this isn’t a return to old-school socialism. Instead, voters seem to be leaning toward practical, social-democratic ideas—ones that offer government support without fully rejecting capitalism. People are simply fed up with policies that favour the rich while ignoring the struggles of everyday families. They’re calling for fairness, not radicalism.

America’s Rightward Drift: The Trump Effect Still Lingers

In contrast, the political story in the United States tells a very different tale. Even after Donald Trump left office in 2020, the Republican Party remains incredibly powerful—and popular.

Trump didn’t win hearts through traditional conservative ideas. Instead, he tapped into a raw frustration brewing among working-class Americans. He spoke about lost factory jobs, unfair trade deals, and an elite political class that seemed disconnected from ordinary life. His messages about “America First” and restoring national pride struck a chord—especially in regions hit hard by globalisation and automation.

Despite scandals and strong opposition, Trump’s brand of politics—nationalist, anti-immigration, and skeptical of global cooperation—continues to dominate the Republican Party. In fact, many voters still see him as someone who “tells it like it is,” even if they don’t agree with everything he says.

It’s a sign of a deeper trend: In the US, cultural identity and economic insecurity have merged, creating a political environment where conservative populism feels like the only answer to many.

India’s Strongman Politics: The Modi Era Continues

Half a world away, India is witnessing its own version of populism under Prime Minister Narendra Modi. His party—the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)—has ruled with a blend of Hindu nationalism, economic ambition, and strong leadership.

Modi is incredibly popular. His supporters praise his development projects, digital push, and efforts to raise India’s profile on the global stage. But critics argue that his leadership is dividing the country along religious lines and weakening its long-standing secular values.

Still, for many Indians—especially the younger generation and the rural poor—Modi represents hope, strength, and pride. They see him as someone who has delivered where previous leaders failed. Whether it’s building roads, providing gas connections to villages, or cleaning up bureaucracy, the BJP’s strong-arm tactics have resonated with large sections of the population.

India’s political direction shows how nationalism can be powerful—especially when combined with promises of economic progress and security.

A Marxist Comeback? Sri Lanka’s Political Wild Card

Then there’s Sri Lanka—a country in crisis, where politics have taken a shocking turn.

For decades, Sri Lanka was governed by familiar faces and powerful families. But after years of financial mismanagement, corruption, and a devastating economic collapse, public trust in mainstream parties has plummeted. Into this void stepped a party many thought had been sidelined for good—the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), a Marxist-Leninist group with a history of revolutionary roots.

Once seen as radical and even dangerous, the JVP has rebranded itself as a disciplined, modern political force. Today, it speaks directly to the country’s suffering masses: those without jobs, struggling to buy food, and fed up with elite corruption.

The party talks about fair wealth distribution, workers’ rights, and standing up to foreign economic pressures. While their ideas are left-leaning, their growing support is driven more by public frustration with current political leaders than by any shift toward Marxism by the public or any move away from it by the JVP.

Sri Lanka’s case is unique—but not isolated. Across the world, when economies collapse and inequality soars, people often turn to ideologies that offer hope and accountability—even if they once seemed extreme.

A Global Puzzle: Why Are Politics So Contradictory Now?

So what’s really going on? Why are some countries swinging left while others turn right?

The answer lies in the global crises and rapid changes of the past two decades. The 2008 financial crash, worsening inequality, mass migrations, terrorism fears, the COVID-19 pandemic, and now climate change have all shaken public trust in traditional politics.

Voters everywhere are asking the same questions: Who will protect my job? Who will fix healthcare? Who will keep us safe? The answers they choose depend not just on ideology, but on their unique national experiences and frustrations.

In countries where people feel abandoned by global capitalism, they may choose left-leaning parties that promise welfare and fairness. In others, where cultural values or national identity feel under threat, right-wing populism becomes the answer.

And then there’s the digital revolution. Social media has turbocharged political messaging. Platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube allow both left and right movements to reach people directly—bypassing traditional media. While this has given power to progressive youth movements, it’s also allowed misinformation and extremist views to flourish, deepening polarisation.

Singapore: The Legacy of Pragmatic Leadership and Technocratic Governance

Singapore stands as a unique case in the global political landscape, embodying a model of governance that blends authoritarian efficiency with capitalist pragmatism. The country’s political identity has been shaped largely by its founding Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, often regarded as a political legend for transforming a resource-poor island into one of the most prosperous and stable nations in the world. His brand of leadership—marked by a strong central government, zero tolerance for corruption, and a focus on meritocracy—has continued to influence Singapore’s political ideology even after his passing. The ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), which has been in power since independence, remains dominant, but it has had to adapt to a new generation of voters demanding more openness, transparency, and participatory governance.

Despite criticisms of limited political pluralism, Singapore’s model is often admired for its long-term planning, public sector efficiency, and ability to balance rapid economic development with social harmony. In an era of rising populism and political fragmentation elsewhere, Singapore’s consistent technocratic approach provides a compelling counter-narrative—one that prioritises stability, strategic foresight, and national cohesion over ideological extremes.

What the Future Holds

We are living in a time where political boundaries are blurring, and old labels don’t always fit. Left and right are no longer clear-cut. Populists can be socialist or ultra-conservative. Liberals may support strong borders. Conservatives may promote welfare if it wins votes.

What matters now is trust—people are voting for those who seem to understand their pain, not just those with polished manifestos.

As economic instability continues and global challenges multiply, this ideological tug-of-war is likely to intensify. Whether we see more progressive reforms or stronger nationalist movements will depend on how well political leaders can address real issues, from food security to climate disasters.

One thing is clear: the global political wave is still rising. And it’s carrying countries in very different directions.

Conclusion

The current wave of global political ideology is defined by its contradictions, complexity, and context-specific transformations. While some nations are experiencing a resurgence of progressive, left-leaning movements—such as Australia’s Labour Party, Canada’s New Democratic Party, and Sri Lanka’s Marxist-rooted JVP—others are gravitating toward right-wing populism, nationalist narratives, and conservative ideologies, as seen in the continued strength of the US Republican Party and the dominant rule of Narendra Modi’s BJP in India. Amid this ideological tug-of-war, Singapore presents a unique political model. Eschewing populist swings, it has adhered to a technocratic, pragmatic form of governance rooted in the legacy of Lee Kuan Yew, whose leadership transformed a struggling post-colonial state into a globally admired economic powerhouse. Singapore’s emphasis on strategic planning, meritocracy, and incorruptibility provides a compelling contrast to the ideological turbulence in many democracies.

What ties these divergent trends together is a common undercurrent of discontent with traditional politics, growing inequality, and the digital revolution’s impact on public discourse. Voters across the world are searching for leaders and ideologies that promise clarity, security, and opportunity amid uncertainty. In mature democracies, this search has split into dual pathways—either toward progressive reform or nostalgic nationalism. In emerging economies, political shifts are even more fluid, influenced by economic distress, youth activism, and demands for institutional change.

Ultimately, the world is witnessing not a single ideological revolution, but a series of parallel recalibrations. These shifts do not point to the triumph of one ideology over another, but rather to the growing necessity for adaptive, responsive, and inclusive governance. Whether through leftist reforms, right-wing populism, or technocratic stability like Singapore’s, political systems will increasingly be judged not by their ideological purity but by their ability to address real-world challenges, unite diverse populations, and deliver tangible outcomes for citizens. In that respect, the global political wave is not simply a matter of left vs. right—it is a test of resilience, innovation, and leadership in a rapidly evolving world.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT , Malabe. He is also the author of the “Doing Social Research and Publishing Results”, a Springer publication (Singapore), and “Samaja Gaveshakaya (in Sinhala). The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the institution he works for. He can be contacted at saliya.a@slit.lk and www.researcher.com)

Features

An opportunity to move from promises to results

The local government elections, long delayed and much anticipated, are shaping up to be a landmark political event. These elections were originally due in 2023, but were postponed by the previous government of President Ranil Wickremesinghe. The government of the day even defied a Supreme Court ruling mandating that elections be held without delay. They may have feared a defeat would erode that government’s already weak legitimacy, with the president having assumed office through a parliamentary vote rather than a direct electoral mandate following the mass protests that forced the previous president and his government to resign. The outcome of the local government elections that are taking place at present will be especially important to the NPP government as it is being accused by its critics of non-delivery of election promises.

Examples cited are failure to bring opposition leaders accused of large scale corruption and impunity to book, failure to bring a halt to corruption in government departments where corruption is known to be deep rooted, failure to find the culprits behind the Easter bombing and failure to repeal draconian laws such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act. In the former war zones of the north and east, there is also a feeling that the government is dragging its feet on resolving the problem of missing persons, those imprisoned without trial for long periods and return of land taken over by the military. But more recently, a new issue has entered the scene, with the government stating that a total of nearly 6000 acres of land in the northern province will be declared as state land if no claims regarding private ownership are received within three months.

The declaration on land to be taken over in three months is seen as an unsympathetic action by the government with an unrealistic time frame when the land in question has been held for over 30 years under military occupation and to which people had no access. Further the unclaimed land to be designated as “state land” raises questions about the motive of the circular. It has undermined the government’s election campaign in the North and East. High-level visits by the President, Prime Minister, and cabinet ministers to these regions during a local government campaign were unprecedented. This outreach has signalled both political intent and strategic calculation as a win here would confirm the government’s cross-ethnic appeal by offering a credible vision of inclusive development and reconciliation. It also aims to show the international community that Sri Lanka’s unity is not merely imposed from above but affirmed democratically from below.

Economic Incentives

In the North and East, the government faces resistance from Tamil nationalist parties. Many of these parties have taken a hardline position, urging voters not to support the ruling coalition under any circumstances. In some cases, they have gone so far as to encourage tactical voting for rival Tamil parties to block any ruling party gains. These parties argue that the government has failed to deliver on key issues, such as justice for missing persons, return of military-occupied land, release of long-term Tamil prisoners, and protection against Buddhist encroachment on historically Tamil and Muslim lands. They make the point that, while economic development is important, it cannot substitute for genuine political autonomy and self-determination. The failure of the government to resolve a land issue in the north, where a Buddhist temple has been put up on private land has been highlighted as reflecting the government’s deference to majority ethnic sentiment.

The problem for the Tamil political parties is that these same parties are themselves fractured, divided by personal rivalries and an inability to form a united front. They continue to base their appeal on Tamil nationalism, without offering concrete proposals for governance or development. This lack of unity and positive agenda may open the door for the ruling party to present itself as a credible alternative, particularly to younger and economically disenfranchised voters. Generational shifts are also at play. A younger electorate, less interested in the narratives of the past, may be more open to evaluating candidates based on performance, transparency, and opportunity—criteria that favour the ruling party’s approach. Its mayoral candidate for Jaffna is a highly regarded and young university academic with a planning background who has presented a five year plan for the development of Jaffna.

There is also a pragmatic calculation that voters may make, that electing ruling party candidates to local councils could result in greater access to state funds and faster infrastructure development. President Dissanayake has already stated that government support for local bodies will depend on their transparency and efficiency, an implicit suggestion that opposition-led councils may face greater scrutiny and funding delays. The president’s remarks that the government will find it more difficult to pass funds to local government authorities that are under opposition control has been heavily criticized by opposition parties as an unfair election ploy. But it would also cause voters to think twice before voting for the opposition.

Broader Vision

The government’s Marxist-oriented political ideology would tend to see reconciliation in terms of structural equity and economic justice. It will also not be focused on ethno-religious identity which is to be seen in its advocacy for a unified state where all citizens are treated equally. If the government wins in the North and East, it will strengthen its case that its approach to reconciliation grounded in equity rather than ethnicity has received a democratic endorsement. But this will not negate the need to address issues like land restitution and transitional justice issues of dealing with the past violations of human rights and truth-seeking, accountability, and reparations in regard to them. A victory would allow the government to act with greater confidence on these fronts, including possibly holding the long-postponed provincial council elections.

As the government is facing international pressure especially from India but also from the Western countries to hold the long postponed provincial council elections, a government victory at the local government elections may speed up the provincial council elections. The provincial councils were once seen as the pathway to greater autonomy; their restoration could help assuage Tamil concerns, especially if paired with initiating a broader dialogue on power-sharing mechanisms that do not rely solely on the 13th Amendment framework. The government will wish to capitalize on the winning momentum of the present. Past governments have either lacked the will, the legitimacy, or the coordination across government tiers to push through meaningful change.

Obtaining the good will of the international community, especially those countries with which Sri Lanka does a lot of economic trade and obtains aid, India and the EU being prominent amongst these, could make holding the provincial council elections without further delay a political imperative. If the government is successful at those elections as well, it will have control of all three tiers of government which would give it an unprecedented opportunity to use its 2/3 majority in parliament to change the laws and constitution to remake the country and deliver the system change that the people elected it to bring about. A strong performance will reaffirm the government’s mandate and enable it to move from promises to results, which it will need to do soon as mandates need to be worked at to be long lasting.

by Jehan Perera

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoRanil’s Chief Security Officer transferred to KKS

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoRemembering Dr. Samuel Mathew: A Heart that Healed Countless Lives

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoAitken Spence Travels continues its leadership as the only Travelife-Certified DMC in Sri Lanka

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe Broken Promise of the Lankan Cinema: Asoka & Swarna’s Thrilling-Melodrama – Part IV

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoRadisson Blu Hotel, Galadari Colombo appoints Marko Janssen as General Manager

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoCCPI in April 2025 signals a further easing of deflationary conditions

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoA piece of home at Sri Lankan Musical Night in Dubai

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoExpensive to die; worship fervour eclipses piety