Features

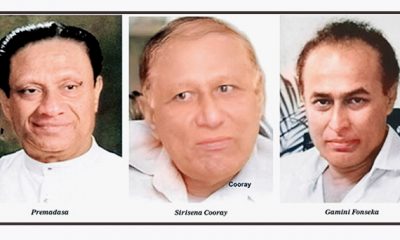

Sirisena Cooray: An Epilogue to a Life in Deeds

Second death anniversary

by Tisaranee Gunasekara

“Who has known the ocean.”

Rachel Carson (Undersea)

Weddings require invitations. Funerals are open spaces. None are barred; anyone can turn up, even sworn enemies. Lankan politicians make use of this openness as a political tool, thus only so far as they remain in active politics.

Sirisena Cooray never missed a funeral until the day he died (the exceptions being his spells abroad and, of course, pandemic times). The habit persisted even after he gave up politics and retired into private life. For him, going to a funeral, near or far, in a mansion or a council flat, was not a political act or even a social duty, but something as natural as talking.

It was part of who he was, a man who loved books but believed in people. Not The People, lionised and sacralised, but people, individuals flawed by life and living. Those interactions motivated him and energised him, giving him a reason to continue to be societally involved, especially during those long uncrowded years after he lost his leader-friend Ranasinghe Premadasa.

Sirisena Cooray’s house was always open, his phone number a public property. People would call, asking for a job, a house, a way in to some official space closed to ordinary citizens. His means were limited, but within that reduced space he would willingly do whatever possible, not because there was anything to gain from such involvement, but because not making the effort was unthinkable. He had left politics, but the sense of responsibility never left him. Whenever he was able to deliver, he gained a quiet sense of satisfaction. Reading was a hobby, meeting friends and travelling enjoyable. Working with and for people was occupation, vocation, life.

Sirisena Cooray belonged to an era in Lankan politics when leaders were approachable and could be approached. You did not need appointments or contacts; you did not have to go through security barriers, each more daunting than the last. You just walked in to meet parliamentarians, ministers, even prime ministers. If you were lucky, you might get a cup of tea, if you were truly fortunate, a solution to your problem. At Sirisena Cooray’s you invariably got that cup of tea. And a sympathetic ear, a promise that an effort would be made, a promise that was always kept even if the effort failed.

Imprinted by Colombo Central

Colombo Central, even when I got to know it in the mid 1990’s, was a village within a city. People had deep roots there, emotional connections and interconnections, and long memories, some handed down like non-corporeal heirlooms. It was loud and quiet, strange and quotidian, an anomaly that was also a microcosm, a place of multitudes which did not consume the individual.

Sirisena Cooray grew up in this place, and at a time when change was in the air, change from British rule to independence, change from colonial governance to electoral democracy. Man was coming into his own as citizen-voter. Even the poorest had something covetable, the franchise. Individual self-improvement was regarded as a necessary component of the larger societal regeneration the new era demanded. Ranasinghe Premadasa began his Sucharitha Movement in these fermenting times. “We grew up hearing stories about the extraordinary activities of this extraordinary young man,” Sirisena Cooray would recall in President Premadasa and I: Our Story. “Even before we met, he was a role model for me.”

Admiration led to imitation (that expression of sincerest flattery would not have been lost on Ranasinghe Premadasa). When he was 12, Sirisena Cooray and his playmates set up a society modelled on the Sucharitha Movement, called Sri Sucharitha Vaag Vardana Lama Samajaya (Children’s society for the improvement of oratorical skills would be a rough translation). There were discussions, and debates, as well as more formal gatherings with the participation of figures of local and national significance. It was the ideal launching pad for a future politician. It was also the best germinal for a life with people, a life of deeds.

Sirisena Cooray once called Ranasinghe Preamadasa a storehouse of concepts. Sirisena Cooray was a storehouse of stories, a repository of oral history of a place bypassed by historians (he was a superb narrator too, despite being an indifferent platform speaker; public audiences are anonymous; you told stories to a known audience).

One story was about bucket lavatories common in Colombo’s poorer areas then (they would survive into the early 1980’s until replaced with water closets by the Premadasa-Cooray combine); and the community of labourers brought down from India by the British to clean them. Every morning, these men and women emptied the often overflowing receptacles of human effluence into open lorries. In this community, death was celebrated the way other people celebrated births and weddings. The life of these people was so unrelentingly wretched, death came as the only possible release.

It was an experience which made a deep impression on Sirisena Cooray. Contrary to a popular misconception, both he and Ranasinghe Premadasa came from middle class backgrounds. But they were born and spent their formative years in Colombo Central, “one of the poorest, most neglected areas of the City,” the despised habitat the wretched of Lanka. It was also a patchwork of primordial pluralities, where Sinhalese, Tamils, and Muslims lived cheek by jowl, literally. Poverty was the common thread that bound them, a bond reinforced by a shared sense of hopelessness.

“All theory is grey,” wrote Goethe in Faust. Sirisena Cooray (whose copy of that epic rests on one of my bookshelves) agreed. Politics, he would insist during interminable arguments, has to be learned not from books but from people and their lives. And for a young man with an awakening interest in politics, Colombo Central was a good place to get to know society’s abiding socio-economic ills. Not just Poverty, but also poverty, not just Unemployment, but also unemployment, not just Homelessness but also homelessness, the nitty-gritty which adds substance to bare figures, not just statistics, but the lived-in experiences.

This knowledge helped make Ranasinghe Premadasa and Sirisena Cooray different from most other leading politicians. It taught them that grand theories and impressive statistics mattered little if they did not positively touch the lived-in experiences of ordinary people. When the Uda Gam housing programme was initiated, detractors especially on the left (a category I too belonged to) decried it saying that the houses were like chicken coops. But for a family living in a shack which was often rented that ‘chicken coop’ was a home beyond dreams.

In a tenement garden, tens of families might have had to share a single water-closet, but that was preferable infinitely to sharing bucket lavatories. To understand these seminal practical differences, it was not enough to visit the poor during election seasons or read about them in books. One must know their lives, daily and intimately. That knowledge enabled the Premadasa-Cooray duo to do more for the poor than any other leader has done before or since. That knowledge, and the sense of responsibility born of it, would compel Sirisena Cooray to do whatever he could to make a difference in one-life-at-a-time, until the day he died.

Race and Class

In Book II of Odyssey, Telemachus, the young son of Odysseus and Penelope, addresses his father’s subjects to enlist their help in beating back his mother’s unwanted suitors who were denuding his father’s property, and thus his patrimony. But Ithacans don’t respond. They are not interested. In the absence of their king, they had gained a limited and provisional agency to live their lives in the way they want.

French Revolution, with its deposing and beheading of Louis XVI and its institution of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, opened the door to a political system which turned subjects into citizens with the right to choose their rulers. People, whose historical role had been limited to labouring and soldering entered political centre stage as electors. In response, political leaders began trafficking in identity politics, invoking ethnic, religious, caste or tribal affiliations as a means to political relevance and electoral gains.

Identity politics might be an elixir for the politicians but for a country and its people it is a poisoned chalice, worsening primordial loyalties and sowing the seeds of future conflicts. This, for instance, was the legacy of 1956.

The way conceived by Ranasinghe Premadasa and practiced by Sirisena Cooray was antipodal: winning over the poor of all communities via tangible improvements in their lives. And to achieve this upward socio-economic mobility of the poor without making the rich feel threatened. This fell into the category of (what Amartya Sen called) a ‘good and just’ development model, radical in intent but non-confrontational in style. Located outside the traditional ‘either-or’ gridlock, this model viewed economic strategy as a series of compromises balancing the interests of diverse socio-economic groups, for a common good. And ‘common good’ is no myth, but a truth which makes life liveable, as we realised last year when we lost it to economic and societal collapse.

The absence of such a balanced economic strategy, together with racism, fuelled the second JVP insurgency. Ranasinghe Premadasa wanted a negotiated end to the conflict, but the JVP was uninterested. Sirisena Cooray formed and led the Ops-Combine (it operated out of his home) to halt the country’s slow fall into anarchy. In the colourful parlance of Deepthi Kumara Gunaratne, “Sirisena Cooray was a former Colombo cinema manager. He used a rural youth who had watched western films to destroy the JVP’s rural youth.

Accordingly, Cooray, who was no racist, defeated racism in the 1980’s through Western thinking” (Sirisena Cooray: Beyond Psychology – ). Sirisena Cooray attributed the success of the Ops- Combine to the new approach he brought in – stop the indiscriminate killing of JVP suspects and focus on the leadership. And, as in economics, think outside the box. For example, “I told the security personnel to get hold of the buses in advance and keep them in the army camps with the drivers and the conductors. When a curfew is declared by the JVP, these buses would be put on the roads. This way we had buses running even on the days of JVP curfews” (President Premadasa and I: Our Story).

When the LTTE broke off negotiations and the second Eelam war started, the Premadasa plan was to win back and consolidate in the East before moving up North. Consolidation meant not militarisation but development. As Sirisena Cooray wrote, “carry out development work and political reforms in the areas, giving the people a decent standard of living and a measure of self-government…

There was a presidential mobile in Vavuniya. Several garment factories were in operation as part of the 200 garment factories programme… Immediately after an area is liberated we would move in and build houses for the people in the area. Initially Mr. Premadasa wanted 1,000 houses to be built in three months in the liberated areas. By the time they were completed, he was dead” (ibid).

When Ranasinghe Premadasa was killed, his development model was abandoned by everyone except Sirisena Cooray. But Sirisena Cooray could do nothing much once he left the party, and then politics. Bereft of the space to influence development policy, he still persisted in doing what he could to make a difference, first through the Premadasa Centre, later on his own.

In the accepted political parlance of Sri Lanka, Sirisena Cooray was a reactionary. He was UNP, he was Premadasa’s man, and that meant, ipso facto, reactionary. In this rigid categorisation, his abiding non-racism and all the development work he helped implement counted for nothing.

Sirisena Cooray never saw himself as a progressive or a reactionary. Those labels didn’t matter to him. For him, as for his leader-friend, the work they did was supposed to speak for itself. He didn’t deal with theories, still less slogans. For him, the deed was what counted. Much of the developmental work he did, both as politician and as ex-politician, remain unknown and uncelebrated. That was the way he wanted it. “Don’t talk about me,” was his standing instruction. No pictures either. The singer was immaterial; only the song counted, and the many lives lightened by its melody.

Features

A long-running identity conflict flares into full-blown war

It was Iran’s first spiritual head of state, the late Ayatollah Khomeini, who singled out and castigated the US as the ‘Great Satan’ in the revolutionary turmoil of the late seventies of the last century that ushered in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The core issue driving the long-running confrontation between Islamic Iran and the West has been religious identity and the seasoned observer cannot be faulted for seeing the explosive emergence of the current war in the Middle East as having the elements of a religious conflict.

It was Iran’s first spiritual head of state, the late Ayatollah Khomeini, who singled out and castigated the US as the ‘Great Satan’ in the revolutionary turmoil of the late seventies of the last century that ushered in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The core issue driving the long-running confrontation between Islamic Iran and the West has been religious identity and the seasoned observer cannot be faulted for seeing the explosive emergence of the current war in the Middle East as having the elements of a religious conflict.

The current crisis in the Middle East which was triggered off by the recent killing of Iranian spiritual head of state Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in a combined US-Israel military strike is multi-dimensional and highly complex in nature but when the history of relations between Islamic Iran and the West, read the US, is focused on the religious substratum in the conflict cannot be glossed over.

In fact it is not by accident that US President Donald Trump resorts to Biblical language when describing Iran in his denunciations of the latter. Iran, from Trump’s viewpoint, is a primordial source of ‘evil’ and if the Middle East has collapsed into a full-blown regional war today it is because of the ‘evil’ influence and doings of Iran; so runs Trump’s narrative. It is a language that stands on par with that used by the architects of the Iranian revolution in the crucial seventies decade.

In other words, it is a conflict between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ and who is ‘good’ and who is ‘evil’ in the confrontation is determined mainly by the observer’s partialities and loyalties which may not be entirely political in kind. It should not be forgotten that one of President Trump’s support bases is the Christian Right in the US and in the rest of the West and the Trump administration’s policy outlook and actions should not be divorced from the needs of this segment of supporters to be fully made sense of.

The reasons for the strong policy tie-up between Rightist administrations in the US in particular and Israel could be better comprehended when the above religious backdrop is taken into consideration. Israel is the principal actor in the ‘Old Testament’ of the Bible and is seen as ‘the Chosen People of God’ and this characterization of Israel ought to explain the partialities of the Republican Right in particular towards Israel. Among other things, this partiality accounts for the strong defence of Israel by the US.

For the purposes of clarity it needs to be mentioned here that the Bible consists of two parts, an ‘Old’ and ‘New Testament’ , and that the ‘New Testament’ or ‘Message’ embodies the teachings of Jesus Christ and the latter teachings are seen as completing and in a sense giving greater substance to the ‘Old Testament’. However, Judaism is based mainly on ‘Old Testament’ teachings and Judaism is distinct from Christianity.

To be sure, the above theological explanation does not exhaust all the reasons for the war in the Middle East but the observer will be allowing an important dimension to the war to slip past if its importance is underestimated.

It is not sufficiently realized that the Iranian Islamic Revolution of 1979 utterly changed international politics and re-wrote as it were the basic parameters that must be brought to bear in understanding it. So important is the Islamic factor in contemporary world politics that it helped define to a considerable degree the new international political order that came into existence with the collapsing of the Cold War and the disintegration of the USSR .

Since the latter developments ‘political Islam’ could be seen as a chief shaping influence of international politics. For example, it accounts considerably for the 9/11 calamity that led to the emergence of fresh polarities in world politics and ushered in political terrorism of a most destructive kind that is today disquietingly visible the world over.

It does not follow from the foregoing that Islam, correctly understood, inspires terrorism of any kind. Islam proclaims peace but some of its adherents with political aims interpret the religion in misleading, divisive ways that run contrary to the peaceful intents of the faith. This is a matter of the first importance that sincere adherents of the faith need to address.

However, there is no denying that the Islamic Revolution in Iran of 1979 has been over the past decades a great shaper of international politics and needs to be seen as such by those sections that are desirous of changing the course of the world for the better. The revolution’s importance is such that it led to US political scientist Dr. Samuel P. Huntingdon to formulate his historic thesis that a ‘Clash of Civilizations’ is upon the world currently.

If the above thesis is to be adopted in comprehending the principal trends in contemporary world politics it could be said that Islam, misleadingly interpreted by some, is pitting a good part of the Southern hemisphere against the West, which is also misleadingly seen by some, as homogeneously Christian in orientation. Whereas, the truth is otherwise. The West is not necessarily entirely synonymous with Christianity, correctly understood.

Right now, what is immediately needed in the Middle East is a ceasefire, followed up by a negotiated peace based on humanistic principles. Turning ‘Spears into Ploughshares’ is a long gestation project but the warring sides should pay considerable attention to former Iranian President Mohammad Khatami’s memorable thesis that the world needs to transition from a ‘Clash of Civilizations’ to a ‘Dialogue of Civilizations’. Hopefully, there would emerge from the main divides leaders who could courageously take up the latter challenge.

It ought to be plain to see that the current regional war in the Middle East is jeopardising the best interests of the totality of publics. Those Americans who are for peace need to not only stand up and be counted but bring pressure on the Trump administration to make peace and not continue on the present destructive course that will render the world a far more dangerous place than it is now.

In the Middle East region a durable peace could be ushered if only the just needs of all sides to the conflict are constructively considered. The Palestinians and Arabs have their needs, so does Israel. It cannot be stressed enough that unless and until the security needs of the latter are met there could be no enduring peace in the Middle East.

Features

The art and science of communicating with your little child

The two input gateways of communication, sight and sound, are quite well developed at birth. In fact, the auditory system becomes functional around 24 weeks in the womb, and the normal newborn can hear quite well after birth. However, the newborn’s vision is a little blurry at birth, and the baby sees the world in shades of grey, while being able only to focus on things 20 to 30 cm (8–12 inches) away. Coincidentally, this is perhaps the exact distance to a mother’s face during breastfeeding. By 2-3 months, there are colour vision capabilities and the ability to track. By 5-8 months, there is depth perception, and by 12 months, there is adult clarity of vision.

By the time a child turns five, his or her brain has already reached 90% of its adult size. This astonishing physical growth is not just happening on its own; it is, to a certain extent, fuelled by experience, and the most vital experience a young child can have is communication with his or her parents.

Modern developmental neuroscience has shifted our understanding of how children learn. We used to think babies were passive sponges, slowly absorbing the world. We now know they are active characters from day one, constantly seeking interaction to build the architecture of their minds. This architecture is not built by apps, vocabulary flashcards, or educational television. It is built through simple, loving, back-and-forth interactions with anyone they come across, but mostly their parents.

The Foundation: Serve and Return (0–12 Months)

Communication with an infant from birth to one year of age begins long before they speak their first word. In the first year, the goal is to master a phenomenon called Serve and Return. This is a basic scenario picked up from the game of tennis. At the start of each game of a set in tennis, a player serves, and the opponent returns the serve. Just imagine a tennis match, where a baby “serves” by making a sound, making eye contact, reaching for a toy, or crying. The job of anyone in the vicinity, who very often are the parents of the baby, is to “return” the ball. If they babble, you babble back. If they point at a cat, you look and say, “Yes, that’s a furry cat!” This simple act does two things. The first is Brain Building, which creates and strengthens neural pathways in the language and emotional centres of the brain. The other is Emotional Security, a thing which teaches a baby that he or she has some help in the learning processes. The baby absorbs the notion that when he or she signals a need, his or her world will respond. This forms the basis of a secure attachment. Scientists have advocated that during this stage, people, especially the parents of a baby, should embrace what is called ‘parentese’. It is the use of a somewhat high-pitched, exaggerated voice. Research has shown that babies pay more attention to parentese than to regular adult speech, helping them to map the sounds of their native language more quickly.

The Language Explosion: Toddlers (1–3 Years)

When a child starts speaking words, the game changes considerably and quite profoundly. This period is defined by a rapid increase in his or her vocabulary and the beginning of grammar. It is very important to narrate everything. The people around, especially the parents, need to become kind of sports commentators for your life. While dressing them, one could say, “First we put on the red sock. After that, we put the other red sock on your left foot.” What we are doing by this is to give them the labels for the world they see.

It is also important to expand, but not truly correct, whatever the child says. If a toddler points to a car and says “Car!”, don’t just say “Yes.” Expand on it: “Yes, that is a big, fast, red car!” You are adding a new vocabulary and grammatical structure through a natural process. If the child says “Me go,” respond with, “Yes, you are going!” rather than correcting and saying “No…, you should say ‘I am going’.”

Toddlers love reading the same book, even one hundred times. While it may be tedious for those around the baby, it is important to realise that such repetition is vital for their learning. They are predicting what comes next, which is a core cognitive skill.

The Preschooler: Building Stories and Logic (3–5 Years)

By age three, the focus shifts from “what” to “why.” Preschoolers are beginning to understand complex emotions, time, and causality. This is the age at which it is best to ask questions which require thought and understanding. Such indirect open-ended questions would sound like “What was the best part of the park today?” or “How do you think that character in the story is feeling?“

A preschooler’s world is full of “big feelings” they cannot yet manage. When they are upset because they cannot have a cookie, avoid saying “Don’t cry over nothing.” Instead, name the emotion: “Don’t cry, you can have a cookie after dinner“. This teaches them emotional literacy. Parents and others around in the home could share stories about when they were little, or make up fantasy tales together. Storytelling teaches sequential logic (beginning, middle, end) and strengthens their imagination.

The Absolute Master Class: Learning Through Play

If communication is the fuel for brain development, play is the engine. For a child under five, play is not a break from learning; play is learning. It is how they explore physics (stacking blocks), mathematics (sorting shapes), social dynamics (sharing toys), and language (pretend play). We can boost their development exponentially by weaving communication into their play.

When a child is playing with blocks, dough, or puzzles, they are building fine motor skills and spatial awareness. It is also useful to use three-dimensional words: “Can you put the blue block on top of the red one?” “The puzzle piece is next to your knee.” One could also ask them to describe the texture: “Is the dough soft or hard?“

Pretend play, such as acting as a doctor, an engineer, a chef, or a superhero, is one of the most cognitively demanding things a child can do. It requires them to understand symbolic thought and to take on another person’s perspective. Join their world as a supporting character, not the director. If they are the doctor, ask, “Doctor, my teddy bear’s tummy hurts. What should I do?” This encourages them to use vocabulary relevant to the scenario and practice complex social problem-solving.

Playing with water, sand, slime, or safe food products allows children to process sensory information. This is the perfect time for descriptive vocabulary. Use contrasting words: wet/dry, hot/cold, sticky/smooth, loud/quiet.

A few special words for parents. You do not need an expensive degree or specialised toys to build your child’s brain. The most powerful tool you have is your own responsiveness. Modern science tells us that the basic recipe for a thriving child is simple: Look at them when they signal you. Respond with warmth and words. Narrate their world and Join their play.

You are not just talking to your child; you are building his or her future, even via just one conversation at a time. So, go on talking to your child and even make him or her a real-life chatterbox.

Dr B. J. C. Perera

Dr B. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paediatrics), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Features

Promoting our beauty and culture to the world

Tourism is very much in the news these days and it’s certainly a good sign to see lots of foreigners checking out Sri Lanka.

Tourism is very much in the news these days and it’s certainly a good sign to see lots of foreigners checking out Sri Lanka.

With this in mind, Ruki’s Model Academy & Agency recently had a spectacular event to select Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka in order to promote Sri Lanka in the international scene.

Nimesha Premachandra was crowned Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka 2026.

She says she owes her success to Ruki (Rukmal Senanayake), the National Director and model trainer, and personality and advocacy trainer Tharaka Gurukanda.

Nimesha is a school teacher by profession, an actress and TV presenter by passion, and an entrepreneur by spirit.

She believes in balancing grace with purpose, and using her platform to inspire women, while promoting the beauty and culture of Sri Lanka to the world. And this is how our Chit-Chat went:

Nimesha Premachandra: Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka 2026

01. How would you describe yourself?

I am a passionate, disciplined, and people-oriented person. I love learning, performing, and guiding others, especially young minds, through education.

02. If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be?

I would probably try to be less self-critical and allow myself to celebrate achievements more often.

03. If you could change one thing about your family, what would it be?

Nothing major. I am grateful for my family’s love and support, which has shaped who I am today.

04. Is Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka your very first pageant?

No. I have been part of pageants before, but Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka is very special because it represents purpose, culture, and global representation.

05. What made you take part in this contest?

I wanted to represent Sri Lanka internationally and use this platform to promote tourism, culture, and women’s empowerment.

06. Obviously, you must be excited about participating in the grand finale, in Vietnam; any special plans for this big event?

Yes, I am extremely excited. My focus is to showcase Sri Lankan elegance, hospitality, and authenticity, while building meaningful connections with participants from around the world.

07. How do you intend promoting tourism, in Sri Lanka, during your rein?

I plan to highlight Sri Lanka’s diverse experiences in culture, heritage, wellness, nature, and local hospitality through media appearances, digital storytelling, and tourism collaborations.

08. School?

Kaluthara Balika. School life played a big role in shaping me. I actively participated in sports and performing arts, which later helped me build confidence as an actress and presenter.

09. Happiest moment?

Being crowned Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka 2026 and seeing the pride in my family’s eyes – definitely one of my happiest moments.

10. What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Peace of mind, good health, and being surrounded by the people I love while doing work that has meaning.

11. Which living person do you most admire?

I most admire Angelina Jolie because she beautifully balances her work as an actress with meaningful humanitarian efforts. She uses her global platform to support refugees, advocate for human rights, and inspire women to be strong, compassionate, and independent.

12. Which is your most treasured possession?

My memories and experiences because they remind me how far I’ve come, and keep me grounded.

13. Your most embarrassing moment?

Like everyone, I’ve had small on-stage mishaps, but they always taught me to laugh at myself and move forward confidently.

14. Done anything daring?

Participating in pageants while balancing teaching, media work, and family life has been one of the boldest and most rewarding decisions I’ve made.

Keen to use her title to promote Sri Lanka globally

15. Your ideal vacation?

A peaceful destination surrounded by nature; somewhere I can relax, reconnect, and experience local culture.

16. What kind of music are you into?

I enjoy soft, soulful music because it helps me relax and stay inspired.

17. Favourite radio station:

I enjoy stations that blend good music with meaningful conversation and positive energy.

18. Favourite TV station:

Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation. It’s where it all began for me. It played a significant role in my journey as a TV presenter and helped shape my confidence and passion for media.

19 What would you like to be born as in your next life?

Someone who continues to inspire others because making a positive impact is what matters most.

20. Any major plans for the future?

I hope to expand my work in media and entrepreneurship while continuing my role as an educator and using my title to promote Sri Lanka globally.

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoAn efficacious strategy to boost exports of Sri Lanka in medium term

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCabinet nod for the removal of Cess tax imposed on imported good

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoA life in colour and song: Rajika Gamage’s new bird guide captures Sri Lanka’s avian soul

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoOverseas visits to drum up foreign assistance for Sri Lanka