Life style

Rice morning , noon ,and night in Sri Lanka

By Zinara Rathnayake

My mother is a good cook. My father is just slightly better. That’s how my younger sister would always describe my parents’ food. She’s right. My mother cooked delicious curries. But my father cooked the food we hold dear.My father grew up in Nabiriththawewa, a small village in Kurunegala.

Unlike his two older brothers who were more interested in going out with their friends, my father accompanied my grandfather to every village wedding. From what I could gather, my grandfather was the chef at every function in the village. He had cooked to feed hundreds.

“I followed him like a thread follows the needle. That’s how I learned to cook,” my father would say.

Although I wish I had met him, I never saw my grandfather, he was already a distant memory when I came to this world.When I was eight years old, my family lived in a small house by the rice fields in my father’s village. My father worked a tedious office job, commuting for hours on a passenger train every day.But when he was home, he would spend time doing two things: gardening and cooking.My father lived a frugal life so he could build a secure future for his two daughters.

He was also a frugal cook, making use of every ingredient so nothing in his kitchen ended up in the waste pit. He mastered the art of delicious snacks, like bath aggala, a Sri Lankan sweet he makes using coconut and leftover rice and that marked our teatime ritual growing up. In Sinhala, aggala are sweet ball-shaped snacks and bath is cooked rice.

At home, teatime was when I cycled home through the rice paddies from the neighbours’ to find my little sister still in her bright sequined nursery dress with her colouring books. Outside, kids would be flying kites as men worked in the fields and women in colourful headwraps reaped golden-yellow paddy with their sharp sickles.

My mother, who was a government school teacher, would be just getting up from her afternoon nap to make tea with powdered milk for us.During the week, teatime meant a cup of tea with a packet of biscuits or a loaf of white bread to dip. But on the weekends, it was my father’s bath aggala, eaten as we sat on the verandah watching the world. Sometimes, my parents would tell us about their childhood. Or we would just watch colonies of bats dart across the evening sky as night fell, and giggle over something my little sister said.

As I look back on those teatimes spent at home, I miss the sounds and colours of those evenings that held us together, and the taste of my father’s bath aggala.It is only now that I understand that, for my father, bath aggala was more than sweet rice balls he made for his family. For him, it was making the most of rice: a grain beloved to him and all Sri Lankans.

The beloved grain

“Udetath bath, dawaltath bath, retath bath”

is a popular Sinhala saying that means “Rice for the morning, afternoon, and night.”

Nothing reflects the essence of my island and people better than that. Rice is not only the main staple for Sri Lankans, it’s more than that.In island kitchens, rice boils every day in clay pots over firewood or steams in electric rice cookers. A pot of steamed rice dominates our tables often, paired with other dishes and condiments. When rice is not cooked this way for breakfast or dinner, another rice-based food blesses our empty plates.

It could be kiribath, a sticky blend of rice and coconut milk eaten for breakfast. Or rice flour is used to make idi appa or idiyappam, discs of steamed thin noodles. Or appa or appam, bowl-shaped snacks with crispy edges and fluffy centres. Or dosa, thin, crisp flatbreads made with a fermented rice-lentil mix. Or levariya, sweet-savoury pockets of rice noodles filled with caramelised coconut.

We use soaked, ground rice to prepare sweetmeats for our New Year every April and when guests come over, we cook rice with aromatics like curry leaves and cinnamon and garnish it with crunchy cashews to prepare golden kaha bath.

When food is scarce, families soak leftover rice to eat in the morning with kiri hodi, a turmeric-infused coconut gravy soured with lime. This modest meal was my father’s favourite breakfast, paired with fresh green chilli.

Rice feeds us, builds us, and shapes us in many ways. This humble grain that thrives in the mud holds a place in every Sri Lankan meal and has crept into every nook and cranny of our society.Rice has a large share of the island’s agriculture, frames its economy, and unpacks our history. And our love for it has given birth to a host of flavourful dishes.I learned how rice grew when we moved to our father’s village. Paddy – the word for the plant and the grain before removing the hull – flourished in the fields thanks to the farmers toiling in the sun.

My father grew paddy in a small field inherited from his parents, which grew enough rice for us. While he readied the field, I would run behind him, getting my feet muddy. Once or twice, I helped him plant seedlings.The earliest stone carving of paddy cultivation in Sri Lanka dates back to 939-940 AD, says Professor Buddhi Marambe, who specialises in weed science and food security. Ancient Sri Lankan rulers built reservoirs to harness rainwater while people developed and preserved rice varieties for more than 3,000 years.

But when the island was colonised by the British in 1815, cash crops like tea and rubber were imposed on farmers to make money for the colonisers. British propaganda campaigns also encouraged people to replace rice with wheat in their diet. “By the 1940s, Sri Lanka had to import 60 percent of the rice needed for the country’s meagre six million population,” says Marambe.In the following decades, refined wheat flour and white bread rose in popularity while native rice was replaced by high-yield varieties to sustain the growing population – varieties that needed chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

In 2020, there was enough locally produced rice to feed Sri Lanka’s population of 21 million, Marambe says. But the then-government abruptly banned synthetic fertilisers in April 2021, forcing farmers to turn to organic fertilisers they were not used to. Farmers lost their harvest, and many deserted their rice fields.

By the time the ban was lifted in November last year, Sri Lanka did not have enough foreign currency to import chemical fertilisers and pesticides. The hard currency shortage also resulted in a fuel crisis, and farmers have to pay more now for reaping and threshing machines.

“Most people [in our village] are abandoning their fields now,” my mother said when I rang her recently. “The machine is charging 240 rupees [$0.66] per minute. They can’t afford it.”

Sri Lanka’s future rice production now depends on a crippled economy and tentative foreign loans that may or may not come.In the past, leftover rice was considered “poor man’s food”, so people stopped eating foods like diya bath (fermented rice porridge with coconut milk) for breakfast, reaching for refined white bread slathered in preservative-laden bottled jam instead.

But, in June, food inflation was more than 60 percent in Sri Lanka and has since kept climbing. Prices soar daily, and most low-income families eat just one or two meals a day. As people rethink their food choices, frugal cooking has made a comeback.

My parents no longer buy biscuits or white bread. A packet of biscuits that cost 200 Sri Lankan rupees ($0.55) a week ago is now 600 rupees ($1.65). “Who would pay that much for biscuits,” my mother said. She wants me to bring her some from India, where I’m currently travelling.My father makes bath aggala more often now. It’s a dish he learned to make by watching his parents and older sisters, he told me recently on the phone.

When my father was a teenager, Sri Lanka was battling drought and an economic crisis in the 1970s. Even though his family had land to grow rice, there wasn’t enough water. So my grandparents made the most of what was available.

“They told us never to throw away rice, not even a single grain of it,” my father said. “When I saw a little boy digging in a dustbin for food at school, I realised what it means to have food on the table.”

Rice and coconuts

I don’t remember us ever buying rice. Even when I left home to live in Colombo, my parents would visit me with tightly packed grocery bags of rice from my father’s fields. But recently when I called home, my mother said she might have to buy rice for the first time in her life.

“The [threshing] machine will only come if we give them diesel,” my mother said. “And we can’t get diesel.”

Many families in the village are now eating diya bath in the morning, my mother said.

Making diya bath involves a few steps if you, like my father, want to eat it hot. Many people eat diya bath cold, which is faster.

If there is rice left over after dinner, my father soaks it in water, letting it soak overnight and draining it the next morning. Then he heats up the coconut milk in a pot, adds dried red chilli, curry leaves, onion, salt, half a teaspoon of turmeric powder, and Maldive fish flakes (dried, cured tuna fish), and lets it simmer.

For sourness, he squeezes in half a lime or adds a few pods of dark brown sun-dried tamarind. (This concoction alone is called kiri hodi). When it’s ready, my father pours it, piping hot, onto a bowl of rice and eats it with fresh green chilli and, sometimes, fried dried fish.

Cold diya bath

is a no-cook meal: mix two cups of coconut milk with one cup of soaked rice. Then add thinly-sliced red onion, two tablespoons of lime juice, three-four roasted dried red chillies, one teaspoon of grated Maldive fish, and salt to taste. If you like it sourer, squeeze in some more lime juice.

Some people like fresh green chilli instead of dried red chilli. Maldive fish is optional, but it adds a nice umami punch. Many elders believe that diya bath, with its fermented rice and coconut milk, cools the body and prevents heartburn.

Speaking of coconut milk, when I make diya bath, I reach for coconut milk that comes in sealed cardboard containers but my parents have never bought coconut milk in their life, they make it. My father plucks coconuts from our garden, removes the fibrous outer husk, halves the nut, and scrapes it with a hiramanaya – a traditional grater with a wooden seat for the person to sit while grating. He mixes the grated coconut with water, squeezing it several times with his hands to make coconut milk.

Making coconut milk is laborious, but my parents still do it. If rice is our staple, coconut is its mate. It thickens our curries, binds our sambals, flavours our foods, and balances meals with healthy fats. Coconuts also make our condiments richer to pair with humble rice.

More than aggala

While people usually boil fresh rice for aggala, my father soaks leftover rice to make sugary, coconutty balls with a slight crunch. For him, bath aggala is food security. It is minimising waste.To make this teatime snack, he ferments leftover cooked rice overnight in water. In the morning, he drains and sun-dries the rice until it is crisp, then roasts it for about 20 minutes in a skillet on a low flame, until it turns brown.

When I made bath aggala recently, I roasted the rice for five to eight minutes and switched off the stove before it changed colour, so it stayed white. Do as you like, roasting for longer gives aggala a golden-brown colour and nutty flavour.Using a pestle and mortar, my father grinds the warm, roasted rice until he gets an uneven texture with pieces of broken rice that add a delightful crunch. You can use an electric grinder as I do, just don’t grind it into powder.

Take 250g of this ground rice and add about 100g of grated coconut, half a cup of sugar, half a teaspoon of salt, and half a cup of water. Mix it well with your hands and shape it into little balls. Some people prefer a bit of a spice kick to their aggala, which is easily done by sprinkling a hint of black pepper into the mix.Once ready, always serve with a cup of tea.

My father’s bath aggala is a testimony to Sri Lanka’s longstanding relationship with rice. It bears witness to the island’s often troubled history and present, twisted and framed by politics and economic interests.The road to recovery is long. But for now, I’d like to be lulled into sweet teatimes at home. One bath aggala at a time.

– Al Jazeera

Life style

Bold new vision for Sri Lankan’s tourism

Sri Lanka is rising on the world’s travel radar – a jewel of the sun, drenched beaches, misty tea estates, and hidden waterfalls. Although Thailand dazzles with scale neon lights, bustling party islands and luxury resorts designed to impress, Sri Lanka offers something different, intimacy, authenticity and a luxury that doesn’t shout, it seduces.

As global travel surges and destinations vie for attention, the Deputy Minister of Tourism for Sri Lanka, Professor Ruwan Ranasinghe with deep roots in tourism studies, speaks about elevating Sri Lanka beyond its beautifully raw landscapes into a world class destination that embraces sustainability, technology and community empowerment. We spoke to him and asked what’s next for Sri Lanka and how the island envisions its tourism renaissance over the next few years.

(Q) How do you foresee the tourism strategy direction for the next five years?

(Q) How do you foresee the tourism strategy direction for the next five years?

(A) Sri Lanka’s future tourism strategy is firmly anchored in sustainable and inclusive tourism. The focus is on balancing growth with responsibility: protecting natural and cultural assets while ensuring that communities across the island benefit directly. Diversification into wellness, eco-tourism, heritage, adventure, and rural experiences will be guided by evidence-based planning and inclusivity.

(Q) The key priorities for post pandemic recovery?

(A) Rebuilding trust with clear safety standards and transparent communication.

Inclusive growth by empowering small entrepreneurs and rural communities.

Sustainable practices in site management, energy use, and conservation.

Diversified demand targeting wellness, eco-travel, and long-stay visitors.

Digital transformation to modernize marketing and expand reach.

(Q) With Tourism booming in Thailand and Maldives, what is Sri Lanka’s position in the tourism landscape?

(A) Sri Lanka’s edge lies in offering a compact, diverse, and authentic experience— heritage, wildlife, tea, beaches, spa and wellness—all within short travel times. By positioning itself as a sustainable and inclusive destination, Sri Lanka appeals to travellers who value responsible tourism and meaningful cultural engagement, setting it apart from regional competitors.

(Q) What are your plans for sustainable and responsible growth for tourism?

(A) Sustainability is non-negotiable. Policies include carrying-capacity management, eco-certification, renewable energy incentives, and climate adaptation in coastal and hill-country zones. Inclusivity ensures that local communities share in tourism’s benefits, reinforcing resilience and equity.

(Q) How do we promote ecotourism, protect wildlife and marine ecosystems?

(A) Eco-tourism is being advanced through responsible visitor management, conservation partnerships, and community guardianship. Wildlife parks, marine ecosystems, and coastal zones are protected with stricter codes of conduct, while local communities are empowered as custodians and beneficiaries.

(Q) How can Sri Lanka showcase its position as a tourist destination?

(A) Sri Lanka presents itself as a sustainable, inclusive, and authentic destination. Live craft, cuisine, Ayurveda, and cultural showcases highlight the island’s unique identity, while digital tools ensure global buyers can connect directly with local providers.

(Q) How do we support small tourism entrepreneurs and rural communities?

(A) Inclusive tourism means empowering SMEs and rural communities with finance, skills, and market access. Homestays, village experiences, and community-based tourism routes are promoted to ensure equitable growth and authentic visitor experiences.

(Q) How do you predict the outlook for Sri Lanka’s tourism by 2030?

(A) By 2030, Sri Lanka envisions a tourism industry that is globally recognized for sustainability and inclusivity. Success will be measured not only in arrivals and revenue, but in conservation outcomes, community empowerment, and equitable regional development.

(Q) How will the role of technology and digital marketing help the tourist sector?

(A) Digital platforms and data insights will modernize Sri Lanka’s tourism, ensuring inclusive access for SMEs and smarter targeting of global markets. Technology supports transparency, efficiency, and sustainability, making tourism more resilient and competitive.

(Q) The impact of recent adverse weather and national disaster on tourism?

(A) Sri Lanka faced severe weather and a national disaster in the past months which inevitably disrupted parts of the tourism industry. Some destinations experienced temporary closures, and travel plans were affected. However, the government has acted swiftly: through the national budget and special allocations, resources are being directed to restore infrastructure, support affected communities, and stabilize the tourism sector.

Importantly, the industry’s resilience is evident. Stakeholders across government, private sector, and communities worked together with peaceful and strong dedication to minimize the damage. Recovery measures include targeted promotions to reassure international markets, rebuilding trust in Sri Lanka as a safe destination, and accelerating necessary upgrades.

This collective response demonstrates that Sri Lanka’s tourism is not only recovering, but doing so in a way that is sustainable, inclusive, and future-focused. The adversity has reinforced our commitment to building a sector that can withstand challenges while continuing to deliver authentic, safe, and memorable experiences for visitors.

Life style

Spectrum of elegance

The Prism story

Tiesh is a luxury Sri Lankan jewellery house known for its high-end handcrafted pieces that combine contemporary design with traditional craftsmanship.

Tiesh is a luxury Sri Lankan jewellery house known for its high-end handcrafted pieces that combine contemporary design with traditional craftsmanship.

Recently Tiesh unveiled a fresh vision for contemporary luxury called the Prism Collection.

The Prism Collection is a jewellery line launched by Tiesh that draws its inspiration from the way light refracts and splits into rich, vibrant colours when passing through a prism.

The idea behind this collection is to capture the spectrum of light and translate it into wearable art -jewellery that highlights brilliance, colour and dynamic form.

This is an era where jewellery is more than mere ornamentation – where every piece tells a story. Launched to great acclaim at the brand’s elegant Colombo showroom, this collection is a radiant celebration of light, colour and refined artistry – a body of work that doesn’t just adorn but transforms.

Renowned for its dedication to excellence, Tiesh continues to uphold its legacy of producing jewellery that epitomises luxury, elegance and meticulous craftsmanship. Each Prism creation is thoughtfully designed and expertly crafted using the finest precious stones and the skill of master local artisans, reflecting the brand’s unwavering commitment to quality and detail.

Launched as a festive yet fashion-forward collection, Prism presents a curated selection of jewellery that aligns seamlessly with today’s modern aesthetic. Available in yellow gold, rose gold and white gold; the Prism Collection features an extensive range of designs, including rings, earrings, pendants, necklaces, bracelets, bangles and chains. Each piece is crafted to highlight colour, balance and wearability, appealing to the modern, trend-conscious jewellery lover.

With a proud legacy spanning almost three decades Staying true to this ethos, the Prism Collection places

Sri Lankan sapphires in the spotlight, celebrating their natural colours, textures and rarity. Speaking of the collection, Tiesh Co-Director Ayesh de Fonseka stated, “Prism was created in keeping with the times, contemporary yet timeless. In a time when the nation looks towards renewal, this Collection emerges as a symbol of hope and positive transformation. Reflecting light, colour and clarity, the collection embodies a sense of resilience and betterment. As proud Sri Lankans, we wanted

this collection to showcase the exceptional beauty of our local sapphires alongside other precious stones. These are statement pieces designed for modern lifestyles.”

The collection also embraces customisation, a signature element of the Tiesh experience. Clients are invited to select their preferred gemstones and personalise designs, resulting in truly one-of-a-kind creations that reflect individual style and expression.

With global gold prices reaching historic highs, fine jewellery has inevitably become heavier on the wallet Yet for discerning clients, the conversation is no longer about grams alone

Here customers can adjust stone size, setting style and medal choice to suit their budget. At Tiesh, you’ll notice another surprise – the after-care service such as polishing and maintenance.

The gold at Tiesh remains genuine and hallmarked. In collections such as the Prism line, gemstones and design architecture do most of the talking, while gold becomes the elegant framework rather than the bulk of the piece. In their collections the gemstones carry much of the visual richness. Instead of purchasing a heavy block of gold, the client invests in design, craftsmanship and beauty. So, when gold prices rise globally our jewellery doesn’t escalate at the same pace because gold is not the sole component defining the piece Ayesh pointed out

We create jewellery meant to live with the heavier, not just sit in a vault. At its heart, Tiesh remains more than a jewellery house; it is a family legacy shared by vision, trust and affinity with craftsmanship. And within every shimmering facet of Prism lies that story: a family craft containing to shine, generation after generation.

The Prism collection is now available at the Tiesh showrooms R A de Mel Mawatha Colombo 3.

Life style

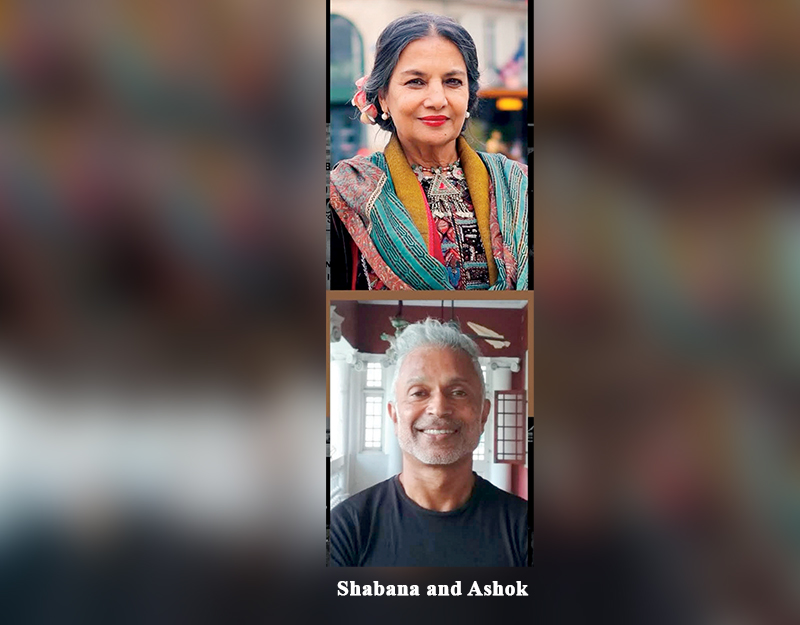

Shabana Azmi in conversation with Ashok Ferrey

Cinema, courage and conversation:

Renowned Indian actress Shabana Azmi brought candour, conviction and a lifetime of cinematic wisdom to the stage recently, in conversation with Sri Lankan author Ashok Ferrey at the HSBC Ceylon Literary and Arts Festival recently at Cinnamon Lakeside Colombo.

In a wide-ranging discussion that traversed five decades of cinema, feminism, censorship and cross-border politics, Azmi reflected on a career spanning over 140 films — dismissing the debate over whether the figure stands at 140 or 160 with characteristic wit. “One hundred and forty is good enough,” she quipped, setting the tone for an evening that blended humour with hard truths.

Ferrey opened the conversation with Ankur, the 1974 classic directed by Shyam Benegal, which marked Azmi’s debut and helped pioneer India’s parallel cinema movement. Azmi credited her formative years at the Film and Television Institute of India for shaping her craft, emphasising that acting is both talent and technique.

“Training polishes the diamond,” she said, rejecting the notion that acting can be mastered in a matter of months. Exposure to international cinema — from Japanese to French and Swedish films — deeply influenced her aesthetic choices, she noted, adding that her upbringing in a household steeped in theatre and poetry further shaped her artistic sensibilities.

Azmi spoke passionately about the delicate balance between emotion and technical precision required of an actor.

“You are in the moment, but you are also watching yourself,” she observed, describing the psychological demands of the profession. “Civilised behaviour expects you to control emotion. Acting demands the opposite.”

The discussion moved to Arth (1982), directed by Mahesh Bhatt, a landmark film in which Azmi portrayed a woman who refuses to reconcile with an unfaithful husband. The decision to let her character walk away — radical at the time — drew scepticism from distributors who doubted Indian audiences would accept such defiance.

“They said it wouldn’t run a single day,” Azmi recalled. Instead, it became both critically acclaimed and commercially successful, resonating deeply with women across India. She described how women began approaching her not as a star but in solidarity, seeking guidance.

“That’s when I realised I have a voice,” she said, marking the beginning of her active involvement in the women’s movement.

Azmi was unequivocal in her stance on patriarchy, describing it as deeply entrenched in South Asian society. While acknowledging that conversations have begun, she warned that social conditioning — including women’s acceptance of domestic violence — remains troubling.

The conversation turned to Fire (1996), directed by Deepa Mehta, a film that sparked controversy for its portrayal of a same-sex relationship between two sisters-in-law. Azmi admitted she took time to consider the role, anticipating backlash.

Encouraged by her husband, lyricist and writer Javed Akhtar, Azmi chose to proceed. The film was initially screened without incident before political groups vandalised theatres in protest. Yet she remains proud of her decision.

“If you can feel empathy for these two women, you can extend that empathy to others — another nation, race, religion or sexuality,” she said, underscoring her belief that art creates a climate of sensitivity where change becomes possible.

On ageing in cinema, Azmi expressed optimism. Unlike earlier decades when actresses were relegated to peripheral roles after 30, today’s industry offers space for senior actors.

She credited contemporaries such as Amitabh Bachchan — whose sustained presence in leading character roles has reshaped industry norms — for broadening opportunities.

The session concluded with reflections on cross-border tensions, prompted by a question about an India–Pakistan cricket match taking place concurrently.

Azmi offered a nuanced perspective, suggesting that while cricket fuels adrenaline, cultural collaborations — particularly film co-productions — could serve as stronger bridges between nations.

“People don’t have a problem with each other. Politics does,” she remarked, advocating for artistic exchange as a means of fostering understanding.

Throughout the evening, Azmi’s words echoed her lifelong belief: that cinema is not merely entertainment but a powerful vehicle for social transformation.

By Ifham Nizam

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction