Features

Preaching in print: The Buddhist journal in the Buddhist Revival

By Uditha Devapriya

Archive images courtesy of the J. R. Jayewardene Centre

The role of the journal in the Buddhist Revival in British Ceylon has never been seriously examined by scholars. Most historical accounts trace the origins of a Buddhist press to the late Dutch and early British periods. The growth of print capitalism held certain implications for the Buddhist backlash against Christian evangelism, as it did in other colonial societies. Yet the momentum of this backlash was never the same: it responded to changing economic and social conditions, and followed a logic and a pattern of its own.

The Buddhists who took over the task of disseminating propaganda against their ideological foes had to fall back on the same institutions that those foes had had recourse to. In 1855 the first Buddhist press was founded from an establishment which had, for three decades, belonged to the Church Missionaries in Kotte. We are told that a second press was set up in Galle a few years later, through the patronage of King Mongkut of Siam and an influential Kandyan chief. These developments spurred monks like Migetuwatte Gunananda Thera to play a leading role in the Christian-Buddhist debates of that period.

The Buddhist press, as it stood at this juncture, was not a little rudimentary. But compared to the meagre resources it had to put up with, it mobilised a rather impressive campaign against its opponents, ironically using the very weapons the latter were using against it. In 1862 Gunananda Thera took the initiative of establishing a Society for the Propagation of Buddhism. Kitsiri Malalgoda has observed that the organisation modelled itself along the lines of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. Over the next few years it published a number of important tracts, many of them written by Gunananda Thera and Hikkaduwe Sri Sumangala Thera, which would form the basis of the Buddhist Revival.

These tracts were published in response to an ever-swelling morass of anti-Buddhist publications, particularly those authored by preachers like Daniel Gogerly. Historians have focused on such publications and given them due emphasis. They have noted that they had a significant impact on the Buddhist Revival, bringing the confrontations between Buddhist monks and Protestant preachers to the notice of Western Theosophists like Colonel Olcott and Madame Blavatsky. What is often missing in these historical evaluations is the way the Buddhist press changed with the arrival of the Theosophists, indeed how both the form and content of these publications altered in light of two key developments: Western, specifically European, interest in Buddhism, and the rise of a Sinhala petty bourgeoisie.

In my view, the role of Western patronage during the Buddhist Revival depended on two factors: the prominent part played by the Theosophists and [paradoxically] their flickering fortunes in the face of an assertive, anti-Theosophist Revival, the latter spearheaded by firebrands like Anagarika Dharmapala; and the conversion to [Theravada] Buddhism of several middle-class Europeans in British Ceylon and Burma. These took Buddhism, as it stood in South and South-East Asia, beyond a Theosophist frame. They also emboldened a fiercely nationalist and anti-imperialist middle-class – or petty bourgeoisie – to take up the leadership of the movement, while partnering with Theosophists and Orientalists who had poured much energy and initiative into the Revival in its early years.

In my view, the role of Western patronage during the Buddhist Revival depended on two factors: the prominent part played by the Theosophists and [paradoxically] their flickering fortunes in the face of an assertive, anti-Theosophist Revival, the latter spearheaded by firebrands like Anagarika Dharmapala; and the conversion to [Theravada] Buddhism of several middle-class Europeans in British Ceylon and Burma. These took Buddhism, as it stood in South and South-East Asia, beyond a Theosophist frame. They also emboldened a fiercely nationalist and anti-imperialist middle-class – or petty bourgeoisie – to take up the leadership of the movement, while partnering with Theosophists and Orientalists who had poured much energy and initiative into the Revival in its early years.

When describing the Sinhala petty bourgeoisie, formed of traders and professionals hemmed in by colonial structures, as anti-imperialist and nationalist, it must be noted that their vision of anti-imperialism and nationalism was necessarily limited, if not insular. Their formation was essentially linked to the spurt in economic activity which accompanied the Colebrooke-Cameron era. The emergence of a plantation bourgeoisie eventually led to the formation of certain ancillary sectors, particularly in the import of foreign merchandise. The Sinhala petty bourgeoisie filled this gap, to some extent. Yet in doing so, it had to pit itself against other ethnic [minority] groups, both local and foreign, which had the upper hand in these activities by virtue of their access to credit and banking facilities.

These were the twin imperatives which determined their ideology: their dependence on subsidiary sectors that in turn were linked to a thriving import sector, and their competition with other ethnic groups. Soon they took the lead in sponsoring, if not funding, a number of important initiatives linked to the Revival, such as the construction of a Pilgrims’ Rest House at Anuradhapura. Naturally enough, they made up the crust of the Sinhala intelligentsia. In combating the influence of other ethnic groups, they eventually fell back on the institutions that had enabled the Buddhist Revival to take off. It was at this juncture that Sinhala traders began lavishly pouring in funds to the publication of new journals, breathing new life to such initiatives in a bid to rechart the contours of the Revival.

As far as their attitude to colonialism was concerned, the Sinhalese traders were as Janus-faced as their ancestors. Despite certain limits and constraints, they had benefitted from the colonial economy. They had turned their attention to the religious dimension of colonial rule, basing their critique of imperialism on the monopoly over education, marriage, and other aspects of civilian life exerted by missionaries. The need to preserve Buddhism, and to restore it to some “antebellum” past, was hence articulated almost purely in cultural terms. This was to be expected: not even after the 1915 riots, a turning point in the Revival, did the most ardent nationalist imagine a Ceylon falling outside the orbit of British rule.

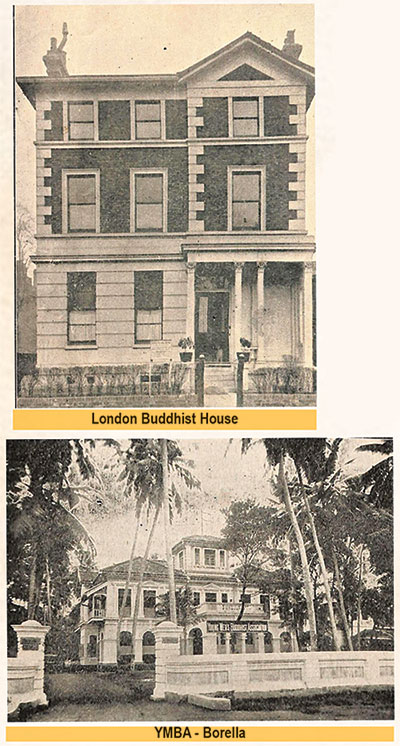

In contrast to their forebearers, whose programme for the revival of Buddhism was limited to the country, these new financiers and patrons imagined a Buddhist world beyond Ceylon. Accordingly, they sought to publish journals and magazines which bridged the gap between the home and the world, reinforcing linkages between Buddhist countries: the repositories of the faith in the Orient on the one hand, and the emerging networks of Buddhist temples and societies in the Occident on the other. They were helped in this by the wealth they had earned from their participation, as bystanders, in the plantation economy.

By its nature, print is both subversive and conservative. The Christian press had used it to advocate the continuation of the status quo; the Buddhist press had used it to advocate a transformation of that status quo. Yet through the press the revivalists sought not so much a radical change in society as a reversal to, and restoration of, an imagined pristine past. In this they were following a tradition begun by the first anti-British insurrectionists, who while opposing British rule clamoured for a restoration of the Kandyan kingdom.

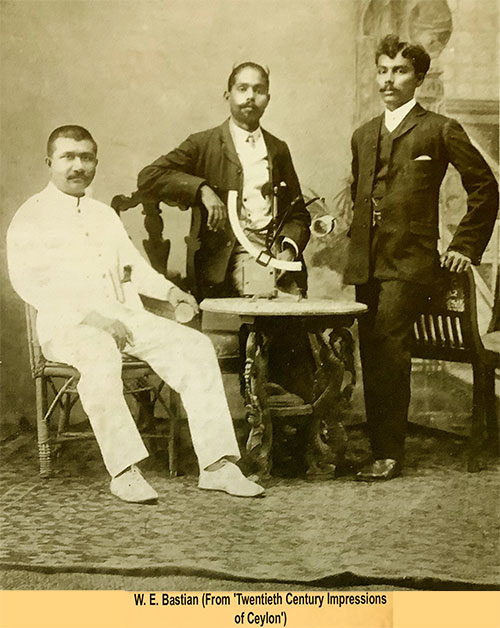

The new patrons of the Buddhist press reinforced this message. If at all, their wealth made them less amenable to revolutionary and radical politics: all they wanted was to exhibit or showcase the “superiority” of their faith. For their part, authorities did not oppose these groups, except when they their activities clashed with the aims of the colonial government. Indeed, they went as far as to praise the Sinhala petty bourgeoisie: here, for instance, is the entry on a wealthy Sinhala trader in Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon:

“Mr. W. E. Bastian was born in Colombo in 1876, and, after receiving his education at the Ananda College, in his native city, joined a local mercantile firm of paper-merchants in the capacity of manager, which post he held for a number of years and relinquished only to set up in business on his own account. The rapid growth of the present business under his management, within the short period it has existed, is an indication of his capacity and integrity. Mr. Bastian is a Buddhist by religion, and enjoys an important standing in his community.” [Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon, page 482]

“Mr. W. E. Bastian was born in Colombo in 1876, and, after receiving his education at the Ananda College, in his native city, joined a local mercantile firm of paper-merchants in the capacity of manager, which post he held for a number of years and relinquished only to set up in business on his own account. The rapid growth of the present business under his management, within the short period it has existed, is an indication of his capacity and integrity. Mr. Bastian is a Buddhist by religion, and enjoys an important standing in his community.” [Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon, page 482]

We have reason to believe that these biographical sketches were written by their very subjects. Nevertheless, that a major colonial work on the geography, economy, politics, and personalities of British Ceylon should feature a Sinhala trader so prominently, allowing him to wax eloquent on his own worth, tells us much about the authorities’ tolerance, indeed encouragement, of such individuals. My argument, basically, is that this is what helped the Sinhala petty bourgeoisie to carry on their campaign for “the preservation of the faith”, and what made them couch the latter objective in terms of cultural polemics, rather than a full-frontal political critique and condemnation of British colonialism per se.

We would do well to recognise the limits of the Sinhala petty bourgeoisie. Through journals like The Buddhist Annual of Ceylon – perhaps the most important such publication from the early 20th century – the revivalists sought nothing less, and nothing more, than a chance to prove the intrinsic worth of their faith. The failure of this revivalist tendency to transition to a full, total critique of colonialism must, in that respect, boil down to what Regi Siriwardena described as the weak and embryonic nature of the Sinhala middle-class: a quality which at once pushed them against other ethnic [foreign and minority] groups, while hindering them from organising a progressive anti-imperialist movement.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

A plural society requires plural governance

The local government elections that took place last week saw a consolidation of the democratic system in the country. The government followed the rules of elections to a greater extent than its recent predecessors some of whom continue to be active on the political stage. Particularly noteworthy was the absence of the large-scale abuse of state resources, both media and financial, which had become normalised under successive governments in the past four decades. Reports by independent election monitoring organisations made mention of this improvement in the country’s democratic culture.

In a world where democracy is under siege even in long-established democracies, Sri Lanka’s improvement in electoral integrity is cause for optimism. It also offers a reminder that democracy is always a work in progress, ever vulnerable to erosion and needs to be constantly fought for. The strengthening of faith in democracy as a result of these elections is encouraging. The satisfaction expressed by the political parties that contested the elections is a sign that democracy in Sri Lanka is strong. Most of them saw some improvement in their positions from which they took reassurance about their respective futures.

The local government elections also confirmed that the NPP and its core comprising the JVP are no longer at the fringes of the polity. The NPP has established itself as a mainstream party with an all-island presence, and remarkably so to a greater extent than any other political party. This was seen at the general elections, where the NPP won a majority of seats in 21 of the country’s 22 electoral districts. This was a feat no other political party has ever done. This is also a success that is challenging to replicate. At the present local government elections, the NPP was successful in retaining its all-island presence although not to the same degree.

Consolidating Support

Much attention has been given to the relative decline in the ruling party’s vote share from the 61 percent it secured in December’s general election to 43 percent in the local elections. This slippage has been interpreted by some as a sign of waning popularity. However, such a reading overlooks the broader trajectory of political change. Just three years ago, the NPP and its allied parties polled less than five percent nationally. That they now command over 40 percent of the vote represents a profound transformation in voter preferences and political culture. What is even more significant is the stability of this support base, which now surpasses that of any rival. The votes obtained by the NPP at these elections were double those of its nearest rival.

The electoral outcomes in the north and east, which were largely won by parties representing the Tamil and Muslim communities, is a warning signal that ethnic conflict lurks beneath the surface. The success of the minority parties signals the different needs and aspirations of the ethnic and religious minority electorates, and the need for the government to engage more fully with them. Apart from the problems of poverty, lack of development, inadequate access to economic resources and antipathy to excessive corruption that people of the north and east share in common with those in other parts of the country, they also have special problems that other sections of the population do not have. These would include problems of military takeover of their lands, missing persons and persons incarcerated for long periods either without trial or convictions under the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act (which permits confessions made to security forces to be made admissible for purposes of conviction) and the long time quest for self-rule in the areas of their predominance

The government’s failure to address these longstanding issues with urgency appears to have caused disaffection in electorate in the north and east. While structural change is necessarily complex and slow, delays can be misinterpreted as disinterest or disregard, especially by minorities already accustomed to marginalisation. The lack of visible progress on issues central to minority communities fosters a sense of exclusion and deepens political divides. Even so, it is worth noting that the NPP’s vote in the north and east was not insignificant. It came despite the NPP not tailoring its message to ethnic grievances. The NPP has presented a vision of national reform grounded in shared values of justice, accountability, development, and equality.

Translating electoral gains into meaningful governance will require more than slogans. The failure to swiftly address matters deemed to be important by the people of those areas appears to have cost the NPP votes amongst the ethnic and religious minorities, but even here it is necessary to keep matters in perspective. The NPP came first in terms of seats won in two of the seven electoral districts of the north and east. They came second in five others. The fact that the NPP continued to win significant support indicates that its approach of equity in development and equal rights for all has resonance. This was despite the Tamil and Muslim parties making appeals to the electorate on nationalist or ethnic grounds.

Slow Change

Whether in the north and east or outside it, the government is perceived to be slow in delivering on its promises. In the context of the promise of system change, it can be appreciated that such a change will be resisted tooth and nail by those with vested interests in the continuation of the old system. System change will invariably be resisted at multiple levels. The problem is that the slow pace of change may be seen by ethnic and religious minorities as being due to the disregard of their interests. However, the system change is coming slow not only in the north and east, but also in the entire country.

At the general election in December last year, the NPP won an unprecedented number of parliamentary seats in both the country as well as in the north and east. But it has still to make use of its 2/3 majority to make the changes that its super majority permits it to do. With control of 267 out of 339 local councils, but without outright majorities in most, it must now engage in coalition-building and consensus-seeking if it wishes to govern at the local level. This will be a challenge for a party whose identity has long been built on principled opposition to elite patronage, corruption and abuse of power rather than to governance. General Secretary of the JVP, Tilvin Silva, has signaled a reluctance to form alliances with discredited parties but has expressed openness to working with independent candidates who share the party’s values. This position can and should be extended, especially in the north and east, to include political formations that represent minority communities and have remained outside the tainted mainstream.

In a plural and multi-ethnic society like Sri Lanka, democratic legitimacy and effective governance requires coalition-building. By engaging with locally legitimate minority parties, especially in the north and east, the NPP can engage in principled governance without compromising its core values. This needs to be extended to the local government authorities in the rest of the country as well. As the 19th century English political philosopher John Stuart Mill observed, “The worth of a state in the long run is the worth of the individuals composing it,” and in plural societies, that worth can only be realised through inclusive decision-making.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Commercialising research in Sri Lanka – not really the healthiest thing for research

In the early 2000s, a colleague, returning to Sri Lanka after a decade in a research-heavy first world university, complained to me that ‘there is no research culture in Sri Lanka’. But what exactly does having a ‘research culture’ mean? Is a lot of funding enough? What else has stopped us from working towards a productive and meaningful research culture? A concerted effort has been made to improve the research culture of state universities, though there are debates about how healthy such practices are (there is not much consideration of the same in private ‘universities’ in Sri Lanka but that is a discussion for another time). So, in the 25 years since my colleague bemoaned our situation, what has been happening?

What is a ‘research culture’?

A good research culture would be one where we – academics and students – have the resources to engage productively in research. This would mean infrastructure, training, wholesome mentoring, and that abstract thing called headspace. In a previous Kuppi column, I explained at length some of the issues we face as researchers in Sri Lankan universities, including outdated administrative regulations, poor financial resources, and such aspects. My perspective is from the social sciences, and might be different to other disciplines. Still, I feel that there are at least a few major problems that we all face.

Number one: Money is important.

Take the example American universities. Harvard University, according to Harvard Magazine, “received $686.5 million in federally sponsored research grants” for the fiscal year of 2024 but suddenly find themselves in a bind because of such funds being held back. Research funds in these universities typically goes towards building and maintenance of research labs and institutions, costs of equipment, material and other resources and stipends for graduate and other research assistants, conferences, etc. Without such an infusion of money towards research, the USA would not have been able to attracts (and keeps) the talent and brains of other countries. Without a large amount of money dedicated for research, Sri Lankan state universities, too, will not have the research culture it yearns for. Given the country’s austere economic situation, in the last several years, research funds have come mainly from self-generated funds and treasury funds. Yet, even when research funds are available (they are usually inadequate), we still have some additional problems.

Number two: Unending spools of red tape

In Sri Lankan universities red tape is endless. An MoU with a foreign research institution takes at least a year. Financial regulations surrounding the award and spending of research grants is frustrating.

Here’s a personal anecdote. In 2018, I applied for a small research grant from my university. Several months later, I was told I had been awarded it. It comes to me in installments of not more than Rs 100,000. To receive this installment, I must submit a voucher and wait a few weeks until it passes through various offices and gains various approvals. For mysterious financial reasons, asking for reimbursements is discouraged. Obviously then, if I were working on a time-sensitive study or if I needed a larger amount of money for equipment or research material, I would not be able to use this grant. MY research assistants, transcribers, etc., must be willing to wait for their payments until I receive this advance. In 2022, when I received a second advance, the red tape was even tighter. I was asked to spend the funds and settle accounts – within three weeks. ‘Should I ask my research assistants to do the work and wait a few weeks or months for payment? Or should I ask them not to do work until I get the advance and then finish it within three weeks so I can settle this advance?’ I asked in frustration.

Colleagues, who regularly use university grants, frustratedly go along with it; others may opt to work with organisations outside the university. At a university meeting, a few years ago, set up specifically to discuss how young researchers could be encouraged to do research, a group of senior researchers ended the meeting with a list of administrative and financial problems that need to be resolved if we want to foster ‘a research culture’. These are still unresolved. Here is where academic unions can intervene, though they seem to be more focused on salaries, permits and school quotas. If research is part of an academic’s role and responsibility, a research-friendly academic environment is not a privilege, but a labour issue and also impinges on academic freedom to generate new knowledge.

Number three: Instrumentalist research – a global epidemic

The quality of research is a growing concern, in Sri Lanka and globally. The competitiveness of the global research environment has produced seriously problematic phenomena, such as siphoning funding to ‘trendy’ topics, the predatory publications, predatory conferences, journal paper mills, publications with fake data, etc. Plagiarism, ghost writing and the unethical use of AI products are additional contemporary problems. In Sri Lanka, too, we can observe researchers publishing very fast – doing short studies, trying to publish quickly by sending articles to predatory journals, sending the same article to multiple journals at the same time, etc. Universities want more conferences rather than better conferences. Many universities in Sri Lanka have mandated that their doctoral candidates must publish journal articles before their thesis submission. As a consequence, novice researchers frequently fall prey to predatory journals. Universities have also encouraged faculties or departments to establish journals, which frequently have sub-par peer review.

Alongside this are short-sighted institutional changes. University Business Liankage cells, for instance, were established as part of the last World Bank loan cycle to universities. They are expected to help ‘commercialise’ research and focuses on research that can produce patents, and things that can be sold. Such narrow vision means that the broad swathe of research that is undertaken in universities are unseen and ignored, especially in the humanities and social sciences. A much larger vision could have undertaken the promotion of research rather than commercialisation of it, which can then extend to other types of research.

This brings us to the issue of what types of research is seen as ‘relevant’ or ‘useful’. This is a question that has significant repercussions. In one sense, research is an elitist endeavour. We assume that the public should trust us that public funds assigned for research will be spent on worth-while projects. Yet, not all research has an outcome that shows its worth or timeliness in the short term. Some research may not be understood other than by specialists. Therefore, funds, or time spent on some research projects, are not valued, and might seem a waste, or a privilege, until and unless a need for that knowledge suddenly arises.

A short example suffices. Since the 1970s, research on the structures of Sinhala and Sri Lankan Tamil languages (sound patterns, sentence structures of the spoken versions, etc.) have been nearly at a standstill. The interest in these topics are less, and expertise in these areas were not prioritised in the last 30 years. After all, it is not an area that can produce lucrative patents or obvious contributions to the nation’s development. But with digital technology and AI upon us, the need for systematic knowledge of these languages is sorely evident – digital technologies must be able to work in local languages to become useful to whole populations. Without a knowledge of the structures and sounds of local languages – especially the spoken varieties – people who cannot use English cannot use those devices and platforms. While providing impetus to research such structures, this need also validates utilitarian research.

This then is the problem with espousing instrumental ideologies of research. World Bank policies encourage a tying up between research and the country’s development goals. However, in a country like ours, where state policies are tied to election manifestos, the result is a set of research outputs that are tied to election cycles. If in 2019, the priority was national security, in 2025, it can be ‘Clean Sri Lanka’. Prioritising research linked to short-sighted visions of national development gains us little in the longer-term. At the same time, applying for competitive research grants internationally, which may have research agendas that are not nationally relevant, is problematic. These are issues of research ethics as well.

Concluding thoughts

In moving towards a ‘good research culture’, Sri Lankan state universities have fallen into the trap of adopting some of the problematic trends that have swept through the first world. Yet, since we are behind the times anyway, it is possible for us to see the damaging consequences of those issues, and to adopt the more fruitful processes. A slower, considerate approach to research priorities would be useful for Sri Lanka at this point. It is also a time for collective action to build a better research environment, looking at new relationships and collaborations, and mentoring in caring ways.

(Dr. Kaushalya Perera teaches at the Department of English, University of Colombo)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Kaushalya Perera

Features

Melantha …in the spotlight

Melantha Perera, who has been associated with many top bands in the past, due to his versatility as a musician, is now enjoying his solo career, as well … as a singer.

Melantha Perera, who has been associated with many top bands in the past, due to his versatility as a musician, is now enjoying his solo career, as well … as a singer.

He was invited to perform at the first ever ‘Noon2Moon’ event, held in Dubai, at The Huddle, CityMax Hotel, on Saturday, 3rd May.

It was 15 hours of non-stop music, featuring several artistes, with Melantha (the only Sri Lankan on the show), doing two sets.

According to reports coming my way, ‘Noon2Moon’ turned out to be the party of the year, with guests staying back till well past 3.00 am, although it was a 12.00 noon to 3.00 am event.

Having Arabic food

Melantha says he enjoyed every minute he spent on stage as the crowd, made up mostly of Indians, loved the setup.

“I included a few Sinhala songs as there were some Sri Lankans, as well, in the scene.”

Allwyn H. Stephen, who is based in the UAE, was overjoyed with the success of ‘Noon2Moon’.

Says Allwyn: “The 1st ever Noon2Moon event in Dubai … yes, we delivered as promised. Thank you to the artistes for the fab entertainment, the staff of The Huddle UAE , the sound engineers, our sponsors, my supporters for sharing and supporting and, most importantly, all those who attended and stayed back till way past 3.00 am.”

Melantha:

Dubai and

then Oman

Allwyn, by the way, came into the showbiz scene, in a big way, when he featured artistes, live on social media, in a programme called TNGlive, during the Covid-19 pandemic.

After his performance in Dubai, Melantha went over to Oman and was involved in a workshop – ‘Workshop with Melantha Perera’, organised by Clifford De Silva, CEO of Music Connection.

The Workshop included guitar, keyboard and singing/vocal training, with hands-on guidance from the legendary Melantha Perera, as stated by the sponsors, Music Connection.

Back in Colombo, Melantha will team up with his band Black Jackets for their regular dates at the Hilton, on Fridays and Sundays, and on Tuesdays and Thursdays at Warehouse, Vauxhall Street.

Melantha also mentioned that Bright Light, Sri Lanka’s first musical band formed entirely by visually impaired youngsters, will give their maiden public performance on 7th June at the MJF Centre Auditorium in Katubadda, Moratuwa.

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSAITM Graduates Overcome Adversity, Excel Despite Challenges

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoNPP win Maharagama Urban Council

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoJohn Keells Properties and MullenLowe unveil “Minutes Away”

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoASBC Asian U22 and Youth Boxing Championships from Monday

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoDestined to be pope:Brother says Leo XIV always wanted to be a priest

-

Foreign News4 days ago

Foreign News4 days agoMexico sues Google over ‘Gulf of America’ name change

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoRatmalana: An international airport without modern navigational and landing aids

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoDrs. Navaratnam’s consultation fee three rupees NOT Rs. 300