Features

Martin Wickramasinghe and A.G. Fraser

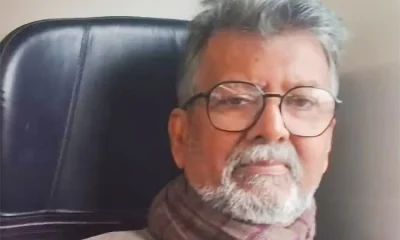

By Uditha Devapriya

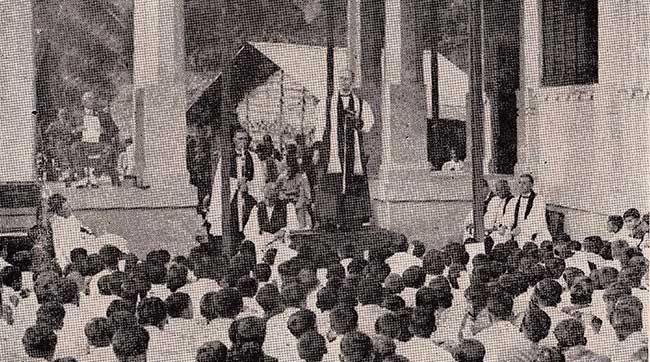

On 7 February 1970, Trinity College, Kandy held its 99th annual Prize Giving. Presided by the then Anglican Bishop of Kurunegala, Lakshman Wickremesinghe, the ceremony featured Martin Wickramasinghe as its Chief Guest. By this point Wickramasinghe had established himself as Sri Lanka’s leading literary figure. A grand old man of 80, he was now writing on a whole range of topics outside culture and literature. His essays addressed some of the more compelling socio-political issues of the day, including unrest among the youth. His speech at the Prize Giving dwelt on these issues and reflected his concerns.

On 7 February 1970, Trinity College, Kandy held its 99th annual Prize Giving. Presided by the then Anglican Bishop of Kurunegala, Lakshman Wickremesinghe, the ceremony featured Martin Wickramasinghe as its Chief Guest. By this point Wickramasinghe had established himself as Sri Lanka’s leading literary figure. A grand old man of 80, he was now writing on a whole range of topics outside culture and literature. His essays addressed some of the more compelling socio-political issues of the day, including unrest among the youth. His speech at the Prize Giving dwelt on these issues and reflected his concerns.

Wickramasinghe’s speech centred on A. G. Fraser, Principal of Trinity from 1904 to 1924. Considered one of the finest headmasters of the day, Fraser broke ground by incorporating vernacular languages to the school syllabus and indigenous cultural elements to the school environment. Fraser was 10 years into his principalship when Wickramasinghe wrote his first novel, Leela. His tenure coincided with some of the more transformative events in British Ceylon, including the McCallum and Manning constitutional reforms. His zeal, especially for indigenising Christianity and missionary education, won him as many allies as it did enemies. Eventually, it encouraged other educationists to follow suit.

The world Fraser saw through was different to the world Wickramasinghe grew up in. Yet in many ways, they were not too different. Fraser had been born to a typical colonial family: his father, Sir Andrew Henderson Leith Fraser, had served as Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal under Lord Curzon. Wickramasinghe, on the other hand, did not obtain a proper education: having left school at an early age, he had been self-educated and self-taught. Both, however, lived through an era of irreversible social transformation, and both played leading roles in that transformation. It is not clear whether the two of them ever actually met. But the two of them shared a disdain for the culture of imitativeness which had become fashionable among the colonial, Westernised middle-class. Through their fields – education in Fraser’s case, literature in Wickramasinghe’s – they strived to change that culture.

By 1970 that culture had changed, and Wickramasinghe’s contribution, as well as Fraser’s, had been widely acknowledged. It is this contribution which Wickramasinghe addressed in his speech at the Prize Giving. Hailing Fraser as a “genuine educationist”, Sri Lanka’s leading Sinhalese litterateur commended Trinity’s greatest principal’s efforts at indigenising the school and the syllabus. In doing so, he categorically refuted the allegation, popular among nationalist ideologues, that Fraser had “created a hostile attitude in the minds of the boys of Trinity to their own culture and language.” From that standpoint, he conceived an intelligent and, in my view, well-rounded critique of chauvinism, which scholars of the man have barely if at all touched in their appraisals of his work.

In a recent, intriguing essay on agrarian utopianism, Dhanuka Bandara invokes Stanley Tambiah’s claim that the concept of gama, pansala, wewa, yaya, so central to the Sinhala nationalist discourse, emerged from Martin Wickramasinghe’s work. To a considerable extent, this is true, and Dhanuka goes to great lengths to show it was. Wickramasinghe’s essays – including those on Sinhalese culture – depicts an almost pristine indigenous society, not unlike Ananda Coomaraswamy’s vision of Kandyan art and culture.

Comparisons between Wickramasinghe and Coomaraswamy are not as crude as they may appear to be. Both idealised rural Sinhalese culture, and both depicted it as an organic, tightly knit community pitted against the forces of modernity. Yet there were important differences. While Coomaraswamy, as Senake Bandaranayake’s essay on the man clearly argues, sought to preserve Kandyan art and culture throughout his life, his celebration of that culture led him to idealise a feudal, static social order. This critique, of course, can itself be critiqued, particularly by those who harbour a different view on Coomaraswamy and his work. But, in my opinion, it stands in marked contrast to Wickramasinghe’s celebration, not of cultural pristineness, but of cultural synthesis and pluralism.

Indeed, throughout his essays, Wickramasinghe hardly exudes an Arnoldian affirmation of high culture. He does not pretend to uphold a great tradition. He is concerned not with keeping intact the values of a pristine society, but with ensuring continuity and change within a certain framework and environment. Contrary to certain cultural nationalists who may imagine him to be one of them, this framework is neither exclusivist nor chauvinist. That is arguably most evident in his critiques of the vernacularisation of education in the 1950s. While admitting the need for the shift to swabasha, he criticises those who, in the guise of devising a “national” education system, went overboard in their attempts at reviving a dead, supposedly superior past in school curricula and syllabuses.

Wickramasinghe’s Trinity College speech presciently underlies these concerns. Addressing the students’ movement in the West and growing student unrest in Sri Lanka, he traces the angst of the youth to an increasingly fragmented society.

“The two causes peculiar to our country which generate discontent in the students of higher educational institutions and sometimes incite them to revolt are bureaucratic control, and the paternal attitude of the society towards them. The bureaucratic control of higher educational institutions based on foreign traditions and the class system that encouraged exploitation is an inheritance from the English colonial system. And the growth of the paternal attitude of the society to the student population is mainly due to an attempt of Buddhist monks and nationalists to revive the past with its dead culture.”

This is a remarkable observation, at odds with the conventional view of Wickramasinghe as an advocate of an organic, pristine past. He is criticising not just the English colonial system which has survived the transition to independent statehood in Sri Lanka, but also Buddhist monks and nationalists – none less! – who idealise a superior, classical culture and try to revive it everywhere. These issues, he contends, are at the centre of youth unrest, and they have pushed the young to rebel against their elders.

“The attempt to inculcate a blind and meek obedience in boys and girls for their elders and teachers is an attempt to revive the divine rights of kings. Parents deserve love, gratitude and kindness form their sons and daughters, but not surrender. What is required is not blind obedience which creates conscious and unconscious hypocrisy, but discipline on the basis of their own independent and changing culture.”

Here one is struck not merely by the author’s siding with the rebelling youth, but also by his unconditional support for their pursuit of an “independent and changing culture.” It ties in with his own belief in the inevitability of change and transformation, of the sort he and A. G. Fraser encountered and affirmed in their day. Indeed, like Fraser, Wickramasinghe critiques the colonial elite’s dismissal of national culture, yet does not embrace an exclusivist framing of this culture. “The word nationalism,” he comments, “apart from the consciousness of the cultural unity of a community, means chauvinism.” This is a remarkable observation from a man whom cultural nationalists today appropriate as one of them.

Some of his other essays from this time reveal an even more radical view on culture.

“There is a cultural unity among the common people in spite of differences of religion, language, and race. They are not interested in a state religion, communal and religious rights because they instinctively feel that there is an underlying unity in religion and race. Agitation for a state religion and communal rights emanates from a minority of educated people who have lost the ethos of their common culture.”

“Impetus for the Growth of a Multiracial Culture”

It is important to note that such views were entirely in line with A. G. Fraser’s. Fraser’s zeal for indigenisation, which inspired the two most prominent faces of Anglicanism in post-colonial Sri Lanka, Lakdasa de Mel and Lakshman Wickremesinghe, was one rooted not in the narrow frame of “Sinhala Only” and narrow communalism, but in an all-encompassing nationalism. Fraser’s intervention in the 1915 riots, derided by nationalist elites at the time, but defended eloquently by James Rutnam later, shows that to some extent.

Here, for instance, is Fraser speaking at the College Prize Giving in 1908.

“When I came here four years ago I was astonished to find that senior students who hoped to serve amongst their people could neither read nor write their own language… a thorough knowledge of the mother tongue is indispensable to true culture or real thinking power. More, a college fails if it is not producing true citizens and men who are isolated from the masses of their own people by ignorance of their language and thought can never fulfil the part of educated citizens or be the true leaders of their race.”

It would be useful to quote from Wickramasinghe’s 1970 speech.

“A child must adapt and respond to that environment of the greater society to develop his intellectual and creative faculties. If he is trained to adapt and respond only to the environment of his family circle who are mere imitators, the development of his intellectual and creative faculties will be retarded.”

Both Fraser and Wickramasinghe, in other words, are affirming the need for a child to grow amidst his environment, to learn from and absorb it, to adapt to it.Wickramasinghe’s Trinity College speech needs to be reassessed and reappraised. It distils his views on education and indigenous culture, and his critique of extremist and exclusivist variants of cultural nationalism. It is one of the best sources we have on the man’s views on these issues, and it needs to be placed in the context of its time: a year or so after the Prize Giving, Sri Lanka would encounter a widespread youth insurrection, the likes of which it had never encountered before. Martin Wickramasinghe would pass away six years after the Prize Giving, almost 15 years after Fraser’s passing. Fraser’s contribution, and Wickramasinghe’s affirmation of it, underlies a vision of nationalism and culture that was more inclusive, more diverse, and thus more representative of our country and our people.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.

Features

Trade preferences to support post-Ditwah reconstruction

The manner in which the government succeeded in mobilising support from the international community, immediately after the devastating impact of Cyclone Ditwah, may have surprised many people of this country, particularly because our Opposition politicians were ridiculing our “inexperienced” government, in the recent past, for its inability to deal with the international community effectively. However, by now it is evident that the government, with the assistance of the international community and local nongovernmental actors, like major media organisations, has successfully managed the recovery efforts. So, let me begin by thanking them for what they have done so far.

Yet, some may argue that it is not difficult to mobilise the support for recovery efforts from the international community, immediately after any major disaster, and the real challenge is to sustain that support through the next few weeks, months and years. Because the recovery process, more specifically the post-recovery reconstruction process, requires long-term support. So, the government agencies should start immediately to focus on, in addition to initial disaster relief, a longer-term strategy for reconstruction. This is important because in a few weeks’ time, the focus of the global community may shift elsewhere … to another crisis in another corner of the world. Before that happens, the government should take initiatives to get the support from development partners on appropriate policy measures, including exceptional trade preferences, to help Sri Lanka in the recovery efforts through the medium and the long term.

Use of Trade Preferences to support recovery and reconstruction

In the past, the United States and the European Union used exceptional enhanced trade preferences as part of the assistance packages when countries were devastated by natural disasters, similar to Cyclone Ditwah. For example:

- After the devastating floods in Pakistan, in July 2010, the EU granted temporary, exceptional trade preferences to Pakistan (autonomous trade preferences) to aid economic recovery. This measure was a de facto waiver on the standard EU GSP (Generalised Scheme of Preferences) rules. The preferences, which were proposed in October 2010 and were applied until the end of 2013, effectively suspended import duties on 75 types of goods, including textiles and apparel items. The available studies on this waiver indicate that though a significant export hike occurred within a few months after the waiver became effective it did not significantly depress exports by competing countries. Subsequently, Pakistan was granted GSP+ status in 2014.

- Similarly, after the 2015 earthquakes in Nepal, the United States supported Nepal through an extension of unilateral additional preferences, the Nepal Trade Preferences Programme (NTPP). This was a 10-year initiative to grant duty-free access for up to 77 specific Nepali products to aid economic recovery after the 2015 earthquakes. This was also a de facto waiver on the standard US GSP rules.

- Earlier, after Hurricanes Mitch and Georges caused massive devastation across the Caribbean Basin nations, in 1998, severely impacting their economies, the United States proposed a long-term strategy for rebuilding the region that focused on trade enhancement. This resulted in the establishment of the US Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act (CBTPA), which was signed into law on 05 October, 2000, as Title II of the Trade and Development Act of 2000. This was a more comprehensive facility than those which were granted to Pakistan and Nepal.

What type of concession should Sri Lanka request from our development partners?

Given these precedents, it is appropriate for Sri Lanka to seek specific trade concessions from the European Union and the United States.

In the European Union, Sri Lanka already benefits from the GSP+ scheme. Under this arrangement Sri Lanka’s exports (theoretically) receive duty-free access into the EU markets. However, in 2023, Sri Lanka’s preference utilisation rate, that is, the ratio of preferential imports to GSP+ eligible imports, stood at 59%. This was significantly below the average utilisation of other GSP beneficiary countries. For example, in 2023, preference utilisation rates for Bangladesh and Pakistan were 90% and 88%, respectively. The main reason for the low utilisation rate of GSP by Sri Lanka is the very strict Rules of Origin requirements for the apparel exports from Sri Lanka. For example, to get GSP benefits, a woven garment from Sri Lanka must be made from fabric that itself had undergone a transformation from yarn to fabric in Sri Lanka or in another qualifying country. However, a similar garment from Bangladesh only requires a single-stage processing (that is, fabric to garment) qualifies for GSP. As a result, less than half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports to the EU were ineligible for the preferences in 2023.

Sri Lanka should request a relaxation of this strict rule of origin to help economic recovery. As such a concession only covers GSP Rules of Origin only it would impact multilateral trade rules and would not require WTO approval. Hence could be granted immediately by the EU.

United States

Sri Lanka should submit a request to the United States for (a) temporary suspension of the recently introduced 20% additional ad valorem duty and (b) for a programme similar to the Nepal Trade Preferences Programme (NTPP), but designed specifically for Sri Lanka’s needs. As NTPP didn’t require WTO approval, similar concessions also can be granted without difficulty.

Similarly, country-specific requests should be carefully designed and submitted to Japan and other major trading partners.

(The writer is a retired public servant and can be reached at senadhiragomi@gmail.com)

by Gomi Senadhira

Features

Lasting power and beauty of words

Novelists, poets, short story writers, lyricists, politicians and columnists use words for different purposes. While some of them use words to inform and elevate us, others use them to bolster their ego. If there was no such thing called words, we cannot even imagine what will happen to us. Whether you like it or not everything rests on words. If the Penal Code does not define a crime and prescribe a punishment, judges will not be able to convict criminals. Even the Constitution of our country is a printed document.

A mother’s lullaby contains snatches of sweet and healing words. The effect is immediate. The baby falls asleep within seconds. A lover’s soft and alluring words go right into his or her beloved. An army commander’s words encourage soldiers to go forward without fear. The British wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s words still ring in our ears: “… we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender …”

Writers wax eloquent on love. English novelist John Galsworthy wrote: “Love is no hot-house flower, but a wild plant, born of a wet night, born of an hour of sunshine; sprung from wild seed, blown along the road by a wild wind. A wild plant that, when it blooms by chance within the hedge of our gardens, we call a flower; and when it blooms outside we call a weed; but flower or weed, whose scent and colour are always wild.” While living in a world dominated by technology, we often hear a bunch of words that is colourless and often cut to verbal ribbons – “How R U” or “Luv U.” Such words seem to squeeze the life out of language.

Changing medium

Language is a constantly changing medium. New words and forms arrive and old ones die out. Whoever thought that the following Sinhala words would find a place in the Oxford English Dictionary? “Asweddumize, Avurudu, Baila, Kiribath, Kottu Roti, Mallung, Osari, Papare, Walawwa and Watalappan.” With all such borrowed words the English language is expanding and remains beautiful. The language helps us to express subtle ideas clearly and convincingly.

You are judged by the words you use. If you constantly use meaningless little phrases, you will be considered a worthless person. When you read a well-written piece of writing you will note how words jump and laugh on the paper or screen. Some of them wag their tails while others stand back like shy village belles. However, they serve a useful purpose. Words help us to write essays, poems, short stories and novels. If not for the beauty of the language, nobody will read what you write.

If you look at the words meaningfully, you will see some of them tap dancing while others stand to rigid attention. Big or small, all the words you pen form part of the action or part of the narrative. The words you write make your writing readable and exciting. That is why we read our favourite authors again and again.

Editorials

If a marriage is to succeed, partners should respect and love each other. Similarly, if you love words, they will help you to use them intelligently and forcefully. A recent survey in the United States has revealed that only eight per cent of people read the editorial. This is because most editorials are not readable. However, there are some editorials which compel us to read them. Some readers collect such editorials to be read later.

Only a lover of words would notice how some words run smoothly without making a noise. Other words appear to be dancing on the floor. Some words of certain writers are soothing while others set your blood pounding. There is a young monk who is preaching using simple words very effectively. He has a large following of young people addicted to drugs. After listening to his preaching, most of them have given up using illegal drugs. The message is loud and clear. If there is no demand for drugs, nobody will smuggle them into the country.

Some politicians use words so rounded at the edges and softened by wear that they are no longer interesting. The sounds they make are meaningless and listeners get more and more confused. Their expressions are full of expletives the meaning of which is often soiled with careless use of words.

Weather-making

Some words, whether written or spoken, stick like superglue. You will never forget them. William Vergara in his short essay on weather-making says, “Cloud-seeding has touched off one of the most baffling controversies in meteorological history. It has been blamed for or credited with practically all kinds of weather. Some scientists claim seeding can produce floods and hail. Others insist it creates droughts and dissipates clouds. Still others staunchly maintain it has no effect at all. The battle is far from over, but at last one clear conclusion is beginning to emerge: man can change the weather, and he is getting better at it.”

There are words that nurse the ego and heal the heart. The following short paragraph is a good example. S. Radhakrishnan says, “In every religion today we have small minorities who see beyond the horizon of their particular faith, not through religious fellowship is possible, not through the imposition of any one way on the whole but through an all-inclusive recognition that we are all searchers for the truth, pilgrims on the road, that we all aim at the same ethical and spiritual standard.”

There are some words joined together in common phrases. They are so beautiful that they elevate the human race. In the phrase ‘beyond a shadow of doubt’, ‘a shadow’ connotes a dark area covering light. ‘A doubt’ refers to hesitancy in belief. We use such phrases blithely because they are exquisitely beautiful in their structure. The English language is a repository of such miracles of expression that lead to deeper understanding or emphasis.

Social media

Social media use words powerfully. Sometimes they invent new words. Through the social media you can reach millions of viewers without the intervention of the government. Their opinion can stop wars and destroy tyrants. If you use the right words, you can even eliminate poverty to a great extent.

The choice of using powerful words is yours. However, before opening your mouth, tap the computer, unclip a pen, write a lyric or poem, think twice of the effect of your writing. When you talk with a purpose or write with pleasure, you enrich listeners and readers with your marvellous language skills. If you have a command of the language, you will put across your point of view that counts. Always try to find the right words and change the world for a better place for us to live.

By R. S. Karunaratne

karunaratners@gmail.com

Features

Why Sri Lanka Still Has No Doppler Radar – and Who Should Be Held Accountable

Eighteen Years of Delay:

Cyclone Ditwah has come and gone, leaving a trail of extensive damage to the country’s infrastructure, including buildings, roads, bridges, and 70% of the railway network. Thousands of hectares of farming land have been destroyed. Last but not least, nearly 1,000 people have lost their lives, and more than two million people have been displaced. The visuals uploaded to social media platforms graphically convey the widespread destruction Cyclone Ditwah has caused in our country.

The purpose of my article is to highlight, for the benefit of readers and the general public, how a project to establish a Doppler Weather Radar system, conceived in 2007, remains incomplete after 18 years. Despite multiple governments, shifting national priorities, and repeated natural disasters, the project remains incomplete.

Over the years, the National Audit Office, the Committee on Public Accounts (COPA), and several print and electronic media outlets have highlighted this failure. The last was an excellent five-minute broadcast by Maharaja Television Network on their News First broadcast in October 2024 under a series “What Happened to Sri Lanka”

The Agreement Between the Government of Sri Lanka and the World Meteorological Organisation in 2007.

The first formal attempt to establish a Doppler Radar system dates back to a Trust Fund agreement signed on 24 May 2007 between the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) and the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). This agreement intended to modernize Sri Lanka’s meteorological infrastructure and bring the country on par with global early-warning standards.

The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations established on March 23, 1950. There are 193 member countries of the WMO, including Sri Lanka. Its primary role is to promote the establishment of a worldwide meteorological observation system and to serve as the authoritative voice on the state and behaviour of the Earth’s atmosphere, its interaction with the oceans, and the resulting climate and water resources.

According to the 2018 Performance Audit Report compiled by the National Audit Office, the GoSL entered into a trust fund agreement with the WMO to install a Doppler Radar System. The report states that USD 2,884,274 was deposited into the WMO bank account in Geneva, from which the Department of Metrology received USD 95,108 and an additional USD 113,046 in deposit interest. There is no mention as to who actually provided the funds. Based on available information, WMO does not fund projects of this magnitude.

The WMO was responsible for procuring the radar equipment, which it awarded on 18th June 2009 to an American company for USD 1,681,017. According to the audit report, a copy of the purchase contract was not available.

Monitoring the agreement’s implementation was assigned to the Ministry of Disaster Management, a signatory to the trust fund agreement. The audit report details the members of the steering committee appointed by designation to oversee the project. It consisted of personnel from the Ministry of Disaster Management, the Departments of Metrology, National Budget, External Resources and the Disaster Management Centre.

The Audit Report highlights failures in the core responsibilities that can be summarized as follows:

· Procurement irregularities—including flawed tender processes and inadequate technical evaluations.

· Poor site selection

—proposed radar sites did not meet elevation or clearance requirements.

· Civil works delays

—towers were incomplete or structurally unsuitable.

· Equipment left unused

—in some cases for years, exposing sensitive components to deterioration.

· Lack of inter-agency coordination

—between the Meteorology Department, Disaster Management Centre, and line ministries.

Some of the mistakes highlighted are incomprehensible. There is a mention that no soil test was carried out before the commencement of the construction of the tower. This led to construction halting after poor soil conditions were identified, requiring a shift of 10 to 15 meters from the original site. This resulted in further delays and cost overruns.

The equipment supplier had identified that construction work undertaken by a local contractor was not of acceptable quality for housing sensitive electronic equipment. No action had been taken to rectify these deficiencies. The audit report states, “It was observed that the delay in constructing the tower and the lack of proper quality were one of the main reasons for the failure of the project”.

In October 2012, when the supplier commenced installation, the work was soon abandoned after the vehicle carrying the heavy crane required to lift the radar equipment crashed down the mountain. The next attempt was made in October 2013, one year later. Although the equipment was installed, the system could not be operationalised because electronic connectivity was not provided (as stated in the audit report).

In 2015, following a UNOPS (United Nations Office for Project Services) inspection, it was determined that the equipment needed to be returned to the supplier because some sensitive electronic devices had been damaged due to long-term disuse, and a further 1.5 years had elapsed by 2017, when the equipment was finally returned to the supplier. In March 2018, the estimated repair cost was USD 1,095,935, which was deemed excessive, and the project was abandoned.

COPA proceedings

The Committee on Public Accounts (COPA) discussed the radar project on August 10, 2023, and several press reports state that the GOSL incurred a loss of Rs. 78 million due to the project’s failure. This, I believe, is the cost of constructing the Tower. It is mentioned that Rs. 402 million had been spent on the radar system, of which Rs. 323 million was drawn from the trust fund established with WMO. It was also highlighted that approximately Rs. 8 million worth of equipment had been stolen and that the Police and the Bribery and Corruption Commission were investigating the matter.

JICA support and project stagnation

Despite the project’s failure with WMO, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) entered into an agreement with GOSL on June 30, 2017 to install two Doppler Radar Systems in Puttalam and Pottuvil. JICA has pledged 2.5 billion Japanese yen (LKR 3.4 billion at the time) as a grant. It was envisaged that the project would be completed in 2021.

Once again, the perennial delays that afflict the GOSL and bureaucracy have resulted in the groundbreaking ceremony being held only in December 2024. The delay is attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic and Sri Lanka’s economic crisis.

The seven-year delay between the signing of the agreement and project commencement has led to significant cost increases, forcing JICA to limit the project to installing only one Doppler Radar system in Puttalam.

Impact of the missing radar during Ditwah

As I am not a meteorologist and do not wish to make a judgment on this, I have decided to include the statement issued by JICA after the groundbreaking ceremony on December 24, 2024.

“In partnership with the Department of Meteorology (DoM), JICA is spearheading the establishment of the Doppler Weather Radar Network in the Puttalam district, which can realize accurate weather observation and weather prediction based on the collected data by the radar. This initiative is a significant step in strengthening Sri Lanka’s improving its climate resilience including not only reducing risks of floods, landslides, and drought but also agriculture and fishery“.

Based on online research, a Doppler Weather Radar system is designed to observe weather systems in real time. While the technical details are complex, the system essentially provides localized, uptotheminute information on rainfall patterns, storm movements, and approaching severe weather. Countries worldwide rely on such systems to issue timely alerts for monsoons, tropical depressions, and cyclones. It is reported that India has invested in 30 Doppler radar systems, which have helped minimize the loss of life.

Without radar, Sri Lanka must rely primarily on satellite imagery and foreign meteorological centres, which cannot capture the finescale, rapidly changing weather patterns that often cause localized disasters here.

The general consensus is that, while no single system can prevent natural disasters, an operational Doppler Radar almost certainly would have strengthened Sri Lanka’s preparedness and reduced the extent of damage and loss.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s inability to commission a Doppler Radar system, despite nearly two decades of attempts, represents one of the most significant governance failures in the country’s disastermanagement history.

Audit findings, parliamentary oversight proceedings, and donor records all confirm the same troubling truth: Sri Lanka has spent public money, signed international agreements, received foreign assistance, and still has no operational radar. This raises a critical question: should those responsible for this prolonged failure be held legally accountable?

Now may not be the time to determine the extent to which the current government and bureaucrats failed the people. I believe an independent commission comprising foreign experts in disaster management from India and Japan should be appointed, maybe in six months, to identify failures in managing Cyclone Ditwah.

However, those who governed the country from 2007 to 2024 should be held accountable for their failures, and legal action should be pursued against the politicians and bureaucrats responsible for disaster management for their failure to implement the 2007 project with the WMO successfully.

Sri Lanka cannot afford another 18 years of delay. The time for action, transparency, and responsibility has arrived.

(The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of any organization or institution with which the author is affiliated).

By Sanjeewa Jayaweera

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoFinally, Mahinda Yapa sets the record straight

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoHandunnetti and Colonial Shackles of English in Sri Lanka

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCabinet approves establishment of two 50 MW wind power stations in Mullikulum, Mannar region

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoJetstar to launch Australia’s only low-cost direct flights to Sri Lanka, with fares from just $315^

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoGota ordered to give court evidence of life threats

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoAn awakening: Revisiting education policy after Cyclone Ditwah

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoCliff and Hank recreate golden era of ‘The Young Ones’