Features

Innovating systems: Need to build over reinventing the wheel

Modern challenges demand innovative solutions. As society evolves and technology advances, the systems designed to support citizens must keep pace. Yet, time and again, we find ourselves trapped in outdated processes, wasting resources on incremental fixes rather than boldly creating new systems. A recent incident involving a lost mobile phone, reported in this newspaper, and the systemic inefficiencies it revealed underscores why it is time to embrace innovation rather than simply reinvent the wheel.

Modern challenges demand innovative solutions. As society evolves and technology advances, the systems designed to support citizens must keep pace. Yet, time and again, we find ourselves trapped in outdated processes, wasting resources on incremental fixes rather than boldly creating new systems. A recent incident involving a lost mobile phone, reported in this newspaper, and the systemic inefficiencies it revealed underscores why it is time to embrace innovation rather than simply reinvent the wheel.

Case for Inventing New Systems

Inventing new systems allows us to break free from the constraints of outdated frameworks and design solutions that are fit for purpose in a changing world. In the case of phone tracing, a modern system could leverage cutting-edge technologies such as blockchain for secure data handling or AI for real-time tracking. Such innovations would not only enhance efficiency but also address vulnerabilities like hacking, which rendered the old system ineffective.

By building anew, institutions can focus on creating systems that are: Resilient: Designed to withstand emerging threats and challenges. User-Centric: Prioritising the needs and convenience of citizens. Transparent: Ensuring accountability and public trust.

Why Reinventing the Wheel Persists

Despite its limitations, reinventing the wheel persists because it appears easier and less costly in the short term. Decision-makers often fear the risks and disruptions associated with building new systems. However, this mindset ignores the long-term costs of inefficiency and the missed opportunities for innovation.

The Path Forward

To break free from the cycle of reinvention, we must adopt a mindset of innovation: Invest in Research and Development: Allocate resources to design and implement systems that meet modern needs. Foster Collaboration: Engage stakeholders, including citizens, experts, and policymakers, to create inclusive and effective solutions. Embrace Change: Recognise that bold decisions to build anew are often necessary for meaningful progress.

Overseas experiences

In the United States, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has long faced criticism for relying on antiquated tax processing systems. Despite numerous updates and patches, these systems struggle to handle the complexity of modern tax codes and the volume of filings. Efforts to revamp the IRS’s technology have been incremental rather than transformative, resulting in persistent inefficiencies and public frustration.

Similarly, in India, the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) initially relied on legacy systems that were ill-equipped to handle the scale and diversity of transactions. While adjustments were made, these efforts highlighted the limitations of reinventing outdated systems rather than designing new, robust frameworks from scratch.

Examples of Successful Innovation

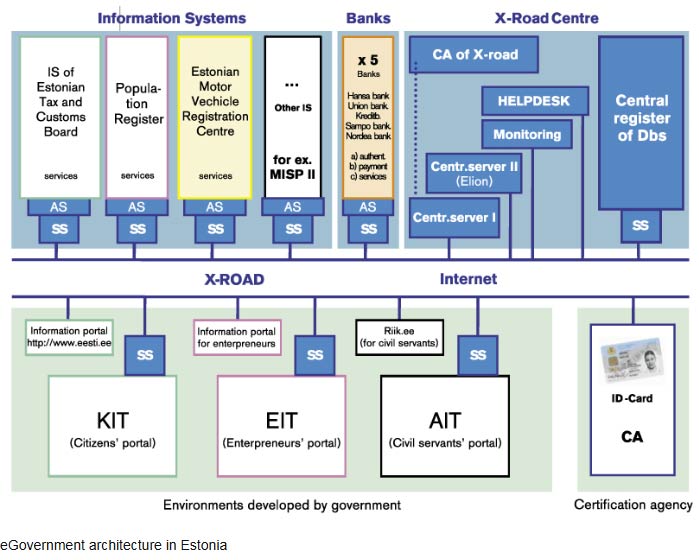

Estonia’s e-Government System is a global leader in digital governance. Instead of attempting to modernise traditional bureaucratic structures, Estonia built an entirely new e-governance system. Citizens can access services like voting, tax filing, and healthcare online through a secure digital platform. This system’s design prioritises transparency, efficiency, and user experience, saving citizens time and fostering trust in government.

Singapore’s Urban Mobility System developed a world-class public transport system using data-driven planning and cutting-edge technology. Instead of retrofitting existing systems, Singapore invented a new approach to urban mobility, integrating autonomous vehicles, cashless payments, and predictive maintenance. This innovation not only improved efficiency but also positioned Singapore as a global leader in smart transportation.

Rwanda’s Drone-Based Healthcare Delivery the government partnered with private companies to deploy drones for delivering medical supplies to remote areas. This innovative system bypassed outdated infrastructure, directly addressing the country’s unique challenges and improving healthcare access.

Learning from Failures to Embrace Innovation

Conversely, when systems are merely reinvented rather than reimagined, they often perpetuate inefficiencies. The European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has faced criticism for repeated reforms that fail to address fundamental issues like sustainability and fairness. By focusing on patchwork solutions, the CAP has struggled to meet the evolving needs of farmers and the environment, demonstrating the risks of clinging to outdated frameworks.

Global Implications of Inefficiency

The consequences of reinventing rather than inventing extend beyond inconvenience and inefficiency. Outdated systems can undermine trust in institutions, stifle innovation, and hinder economic growth. For instance, legacy financial systems in developing countries often exclude large segments of the population from accessing banking services, perpetuating poverty and inequality. By contrast, mobile-based financial innovations like Kenya’s M-Pesa have revolutionized access to banking, empowering millions.

The Need for a Paradigm Shift

Globally, governments and institutions must recognise that sticking to old systems often comes at a higher cost than inventing new ones. However, the reluctance to innovate stems from several factors: Fear of Disruption: Decision-makers often view new systems as risky and disruptive, opting for the perceived safety of incremental changes. Resource Constraints: Developing new systems requires significant investment in time, money, and expertise. Resistance to Change: Institutional inertia and fear of the unknown can stifle creativity and innovation.

Overcoming these barriers requires a shift in mindset, emphasising the long-term benefits of bold, transformative action over the short-term comfort of familiarity.

The Role of Communication and Collaboration

Innovation also demands effective communication and collaboration among stakeholders. The Sri Lankan phone-tracing case highlights the importance of ensuring that all parties—regulatory bodies, service providers, and the public—are informed and aligned. Estonia’s e-government success, for instance, was driven by a coordinated effort involving government, private sector, and citizens. Clear communication about new systems, their benefits, and their usage is crucial to building trust and ensuring adoption.

Barriers to Innovation and Strategies for Overcoming Them

Despite its advantages, inventing new systems faces several obstacles: Institutional Inertia: Established organisations often resist change due to entrenched interests and fear of disruption. Resource Constraints: Designing new systems requires significant investment in expertise, time, and funding, which many institutions are reluctant to allocate. Cultural Resistance: Societal norms and perceptions can hinder the adoption of innovative systems, as seen in the public’s skepticism toward digital governance initiatives in some countries.

Overcoming these barriers requires a combination of leadership, collaboration, and education. Research by many scholars emphasise the importance of visionary leadership in driving systemic innovation. Effective communication and stakeholder engagement are also crucial to building trust and ensuring the adoption of new systems.

The Way Forward: Embracing Innovation

To foster innovation, governments and institutions must prioritise long-term goals over short-term fixes. Policymakers should invest in research and development, adopt agile methodologies, and encourage cross-sector collaboration to design systems that are adaptable and future-proof. As seen in Estonia, Singapore, and Rwanda, the benefits of such investments far outweigh the initial costs.

Moreover, international cooperation can accelerate innovation by sharing best practices and pooling resources. Organizations like the United Nations and the World Bank have a critical role to play in promoting systemic innovation, particularly in developing countries where resource constraints are more pronounced.

Reinventing the wheel may feel familiar, but it is not sustainable in an era of rapid change. The challenges of today require us to invent systems that are resilient, efficient, and responsive. As the incident with the lost phone demonstrates, clinging to outdated frameworks not only wastes resources but also erodes public trust.

By embracing innovation, we can create systems that not only solve current problems but also anticipate and adapt to future challenges. It is time to stop patching the cracks and start building the foundations for a better tomorrow.

The challenges of today cannot be solved by reinventing the wheel. From inefficient phone-tracing mechanisms in Sri Lanka to outdated tax systems in the United States, the costs of clinging to old frameworks are evident. By embracing innovation and inventing new systems, governments and institutions can create solutions that are resilient, efficient, and responsive to modern needs.

Global examples like Estonia’s e-government and Rwanda’s drone-based healthcare delivery demonstrate the transformative potential of new systems. It is time to shift from patching cracks to building robust foundations, ensuring that the systems of tomorrow meet the demands of an ever-changing world. Only by prioritizing innovation over reinvention can we truly unlock progress and improve the lives of citizens worldwide.

Features

‘Reflections on the Continuing Crises of Post-War Sri Lanka’

The Institute of International Studies(IIS) recently published a volume, ‘Reflections on The Continuing Crises of Post-War Sr Lanka’ edited by Professors Amal Jayawardena and Gamini Keerwella. Delivering the keynote address, at its launch on 24 April, at the BMICH, former Foreign Secretary, H. M. G. S. Palihakkara reflected on the context and substance of the publication with particular reference to the challenge before the NPP government to convert the voter support it received into a public policy consensus essential to addressing multiple issues of statecraft at hand.

Excerpts:

We are at a juncture of profound change happening nationally as well as internationally – changes that seem to engender a mixed bag of imponderables and great worry, even danger. While many contend that these changes upend globalised advancement, portend uncertainty and unpredictability, some good is seen by others in that certain disruptions could lead to pathways for course corrections. While this obviously divisive and controversial discourse goes on, what is clear and present is that it’s a world where affairs within and between states are in flux. Some of our neighbourhood commentators put it as a ‘world adrift’ or a world ‘getting unhinged’. The description of this volatility and prescriptions for handling the vortex of churning issues may defy objective analysis but the stark reality is that it represents an unprecedented and defining challenge to the post World War international system or the so-called ‘rules -based order’.

Head winds and tail winds of this flux have begun to manifest with different intensity in different countries constraining their space and capacity to grow sustainably and live securely. For some, the situation may morph into existential issues. Sri Lanka’s case lies somewhere in between it looks, but there is no denying that all will be profoundly affected-especially so for countries like us that are struggling to transit from crisis-recovery stability to a sustainable growth scenario. They are obliged to do this while juggling as prudently as possible, attendant geopolitical conundrums thrown up by the competing interests of power players, leading to difficult and often futile attempt to balance the unbalanceable!

At the national level, a new government of former ‘armed struggle fame’ has assumed office promising constructive change, clean and accountable governance based on the idea of reconciliation and equal citizenship for all. This was a hitherto unseen national common ground crafted by the voters(north-south-east-west) – voters fatigued with corrupt stereo-types. They did so, asking the new government to deliver on this attractive and perhaps the most inclusive post conflict mandate yet.

But the government seems to remain somewhat overwhelmed with this exciting but daunting agenda of public policy making and governance. Challenges include dovetailing the currently apparent economic stability into a growth conducive one; preventing a double jeopardy of economic crisis pain morphing into reform pain; doing all that without falling prey to grinding strategic matrixes of our ‘geopolitical friends’; dealing with some of our closest friends who come bearing gifts like distress money and un-solicited power play advice; how to negotiate with them without simply signing onto their wish lists that seek to requisition our sovereign assets thus leaving little or no room to negotiate even as unequals, let alone as sovereign equals!

To add to these woes of the new government, the incumbency factor seems to be setting in as evidenced by some ham-handed handling of delicate issues both domestic and international.

In this fraught setting, the government has boldly, and one must say correctly, decided to go for local polls. This is obviously not a regime change election but it certainly is a regime test one. The losers at the last elections both big and small, seem to have found common cause in firing the first salvos of the government ‘toppling game’ even as they know very well there is no constitutional way to do regime change for the next five years. The Government, on its part has not done itself any favours by scoring rather heavy in clumsiness index. Waffling continues uncomfortably on several fronts critical to public policy issues of national and international significance.

So this is a daunting inventory of domestic things to do in an international system that has turned volatile- a system in which an oxymoronic situation had long persisted because the alleged ‘ rules-based order‘ continued to be confronted by the reality of power-based practice. As we all know, when in contention, power usually trumps the rules. It happens so often it has become quite a ‘convenient truth’! The crudest and what could even be the most dangerous form of this contradiction is peaking now thanks to the phenomenon known as the Trump Two.

The book ‘Reflections on the Continuing Crises of Post-War Sri Lanka.’, helps us introspect in a context where the country is striving -in fact struggling- to recover from multiple self-made crises and become a self-caring nation under a new but un-tested Government-obviously, a timely thing to do.

Well researched and well sourced work in this volume explore an array of considerations both in empirical and conceptual terms as to how and why , after ending the armed conflict, conflicts by other means have continued spawning multiple crises- occurring in almost regular succession-and in diverse domains e.g. governance, socio-economic, ethnic and religious harmony, political, security, foreign policy and so on.

The purpose here is a comment in the form of my take on what this volume presents to the policy community-both political and bureaucratic:

First, it gives out a yet another alarming read-out of the cost of successive leadership failures in this country- failure to ensure constitutional governance, sustainable and equitable economic growth, reconciliation, accountability, the rule of law and so on. It reminds me of a meeting thirteen years ago, which I had the honour to chair in this very Hall at the BCIS, remembering the late legal legend, HL de Silva.

There my observation was that:

” The diminishing respect for the rule of law diminishes us all. Such erosion will allow impunity to raise its ugly head. Usually, impunity signals the onset of decay. It impairs civilised life and democracy. And it undermines the investment climate. Conversely, the upholding of the rule of law manifestly strengthens sovereignty, pre-empts external calls for intrusive accountability, deters threats to territorial integrity of the nation and facilitates the enjoyment of fruits of citizenship and democracy by all’. http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=52289)

It is ironic but highly appropriate that the authors felt compelled to flag these same ‘reflections’ more than a decade later signifying the extent of the ‘unfinished business’ before us.

Secondly, it brings into sharp relief, the absence in this country of a culture of consensus or common ground in the business of public policy making. This contrast has remained conspicuous because the conscientious voters of this land have repeatedly braved political violence, insurgent violence and terrorist violence to grant that mandate to the elected government to do consensual work towards preventing crises and deterring conflict.

That did not happen of course. The consensual culture wished for by the voters died of political asphyxiation. This was due to the kind of parochialism our rulers have been obsessed with. There was decay in multiple fields – the economy, accountability, rule of law, national security, human security, foreign policy and so on. What is more, the contrary took root and polarisation rolled on fuelled both by those elected to power as well as by those thrown out of power. The former did so to remain in power and the latter to topple and recapture. The economy suffered. Investors ran away. The voters found they have nowhere to run.

This continues to date, even after the voters have once again shown that consensus is possible in this country. There was a country-wide consensual momentum to vote into power the current govt. who promised change to bring about accountability, the rule of law, transparent and corruption free governance and equal citizenship for all plus economic reforms. Rejecting the most, if not all corrupt stereo types and ignoring the usual ethnic and religious divides, voters rallied round a high octane call for that change. But the Govt. seems to be going about exploiting that momentum, if they are going about it at all, in the clumsiest way possible thus losing traction in turning that voter’s consensus into a public policy consensus. And not to be out-done, the losers- big and small- have got back on the usual track to begin the govt toppling game. So, the fact that the responsibility of building common ground lies not only with the government but also with the Opposition has become an inconvenient truth.

A ray of hope emerged when there was an all-party initiative to handle the unfolding ‘Tariff war’. But it looked more like a proforma reaction to a tariff drama by a bull-dozing President of a misfiring superpower, than a genuine domestic compulsion to initiate a consensual process enabling us to negotiate with our foreign interlocutors from a position of policy cohesion and bargaining strength.

This is in contrast to other countries including in South Asia that had the vision and wisdom to go consensual on critical national issues while not ruling out the option of politicians to go parochial on non-critical issues so that they can still mis-lead voters to win elections!

Faced with a looming economic crisis, the Congress – BJP agreement on economic reforms in India under PM Manmohan Singh’s watch in the 1990s paved the way for the robust growth of the Indian economic and geopolitical power today; In Bangladesh, an unprecedented bipartisan understanding on energy esp. its policy on exploiting newly discovered LNG deposits as well as a degree of self-rule to their hill tribe rebels and agreement in Nepal on mainstreaming their rebels are such contrasting examples of public policy consensus in our own sub-region.

They understood that weaponizing national issues for electoral gain can gravely undermine the welfare of the succeeding generation.

So besides these contrasting and rewarding examples and experiences in our own sub region, what is so magical about common ground and why do we have to do it?

We need a consensual economic reform programme that cannot and should not be weaponised for the purpose of regime change undermining stability and predictability , even going beyond the important gauntlet of 2028, when Sri Lanka has to resume the enormous burden of debt repayment,

Going by the Govt’s track record so far, the opposition can count on the Govt. to provide enough vulnerabilities on the non-critical list to exploit and attempt regime change! So it is irrational and irresponsible for the opposition to use imaginary or real faults so early in the game to upend the hard earned macro-economic and social stability as we prepare for the 2028 threshold.

On the geopolitical , foreign relations and governance front, one can do without the disruptive, destabilising and even dangerous contentions like the on-going one advocating that Sri Lanka should formally ‘align and economically integrate’ with its giant neighbour. That country is clearly a party to the principal geo-strategic rivalry in the Indo Pacific that is growing in complexity and intensity. Such a huge change of course for Sri Lanka could invite dangerous target practice by other power players. It would also be naïve to believe that the only way forward for Sri Lanka is a piggy back with India for a ride to economic prosperity on a trickle down basis..

It is a cogent point that it could amount to a ‘strategic capture in connectivity clothing’; that no such template has worked elsewhere in the world and Sri Lanka could thus become a non-self-governing territory where our sovereign assets may be parcelled out to strategic players jostling for power.

Both sides of this contention have overlooked the middle path imperative available for Sri Lanka. That is assiduously working to allay ill-founded or well-founded Indian security fears in a verifiable way using many bilateral tools available including the so called ‘national technical means’ while pressing ahead with equal vigour to deepen and widen ‘negotiated’ economic cooperation in identified areas – not structural integration- with our friendly neighbour. This is the way for Sri Lanka to exploit the competitive and comparative advantage it has with a robustly growing India that can benefit both countries. This is the must do thing. Any asymmetry dictated aligning or integration by momentum or wish list signing without negotiating is ‘the must avoid thing. There are many reasons for this avoidance but the latest and the most explosive one comes from Bangladesh. As a blow back to an asymmetry driven integration and autocratisation of the Hasina regime, Indo-Bangla relations exploded while Bangladesh itself imploded.

There are varying degrees of indo centric trouble in all South Asian countries except may be in Bhutan so much so that some Indian analysts themselves have characterised India’s ‘neighbourhood first policy’ as a ‘neighbourhood lost policy’.

We of course cannot afford such polemical luxury but we do need a domestic consensus to do two things:

‘Assure India about their security fears through bilateral technical means and ‘negotiate’ with India on deep-going economic cooperation. This middle path imperative backed by a bipartisan or consensual common ground will demonstrate our policy consistency and predictability towards India while providing benefits achieved by negotiated mutuality – not solely dictated by asymmetry. To be successful, this needs a domestic consensus here- across the isles of quarrelling members of the legislature- the kind of common ground the late Minister Kadirgamar strenuously worked for- the kind of acts of contrition and consensus that LLRC proposed some decades ago in order to advance post-conflict peace building.

Whether this already is a foregone conclusion or still an open question available to negotiate will become clearer when two crops of indo Lanka MOUs concluded by the former Government as well as the present one, cease to be unseen documents.

Such common understanding is needed not only to pilot our relations with our close and distant friends like India and China but also to deal with a host of other governance and foreign relations issues like accountability and reconciliation which remain externalised because the lack of a domestic understanding to deal with them has made them migrate abroad and morph into diplomatic issues entailing multiple challenges. Some past Govts unsuccessfully tried to address these challenges by actively encouraging international consensus on some of these. They did so, while being unable or unwilling to develop a national consensus on these sensitive matters despite the voters here providing robust mandates to do so. Without a national common ground, external prescriptions by themselves cannot deliver justice to victims. Every unpunished crime has an economic cost in both national and international terms. Most, if not all these failures are principally due to the paucity of a shared understanding here.

Consensus is not something you find in a cupboard! It has to be nurtured. Consensus happens not when you make everybody absolutely happy. It happens when you equitably distribute managed unhappiness among everybody. To some it is a fine art. To others it is a hard-nosed science. Perhaps it is a hybrid . Whatever it is, our voters have done it and found it. The NPP’s resounding election victory was the result. So the winner Government must mould that voters’ consensus into a public policy consensus. They can lose sometime but not too much time as windows may start closing. Policy makers – or ‘pain makers’ as some call them- must make haste slowly. If not, down the road, our succeeding generations may be compelled to launch another valuable book of reflections like this .

My friend Professor Jayadeva Uyangoda in his probing scrutiny about the causes and effects of our crises aptly refers to what he calls ‘a crucial political point’ about the “relationship between the state and society becoming violent and the capacity of the liberal parliamentary democracy to restore peace between the State and society becoming severely limited”. If our policy people don’t get the hybrid our voters have found, it is most likely that the next ‘reflection book’ might say ’peace restoration’ is still work in progress. Hopefully, it will not say restoration has regressed!

On that note of mild happiness, I would like to thank you for your patience.

Features

Expensive to die; worship fervour eclipses piety

Death and dying were in the forefront this last week because of Pope Francis’ end to life. Even while dying he seemed to think of others and with compassion be considerate. He knew of the masses that would gather at St Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican City with concern for him. He was surely weak and ill but wanted to be wheel chaired to the balcony to be seen by those gathered below on East Sunday. He lived through the Easter days and then died on Monday, having left details of how his funeral should be conducted: simple to the utmost. The most obvious of austerity and elimination of ostentation was the coffin the Pope desired he be buried in – a simple stark rectangular wooden box. Usually a pope is buried with personal items and documents in a three nested coffin of cypress, lead and oak. Cypress symbolises humility; the middle coffin of lead preserves the body and secures documents; and elm or oak of the outermost coffin ensures durability and symbolises humility. Pope Francis wanted none of this.

Death and dying were in the forefront this last week because of Pope Francis’ end to life. Even while dying he seemed to think of others and with compassion be considerate. He knew of the masses that would gather at St Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican City with concern for him. He was surely weak and ill but wanted to be wheel chaired to the balcony to be seen by those gathered below on East Sunday. He lived through the Easter days and then died on Monday, having left details of how his funeral should be conducted: simple to the utmost. The most obvious of austerity and elimination of ostentation was the coffin the Pope desired he be buried in – a simple stark rectangular wooden box. Usually a pope is buried with personal items and documents in a three nested coffin of cypress, lead and oak. Cypress symbolises humility; the middle coffin of lead preserves the body and secures documents; and elm or oak of the outermost coffin ensures durability and symbolises humility. Pope Francis wanted none of this.

Funeral; expenses locally

This stark simplicity and great wisdom of choice posed itself against how burials and cremations are conducted in this land of ours. They are often lavish displays, with food and drink flowing and people gathering as if it were a merry social gathering. Coffins are ornate and of course costly. They are satin lined and frilled, with tassels galore and shiny metal handles. People get into debt to make a show of a funeral. Mercifully, to stall such and also help in a need, village and town folk set up funeral committees. Annual contributions with membership, guarantees that the payee or his close relatives receive a decent funeral, the committee meeting expenses.

Cassandra has long wondered why trees have to be brought down and coffins made of its wood, polished to mirror appearance. Why not coffins of artificial wood, hardboard or even reinforced cardboard, more so for cremations. Long ago when at A F Raymond’s funeral parlour to pay in advance for Cass’ funeral, the desk person, answering her question, gave the excuse that people want to spend and insist on wood. Hence the huge cost of a funeral, even the cheapest running to a lakh and more.

Heard over BBC on Wednesday, April 30, that the UK might insist on payment of goods bought, in cash. This move for fear the country may go cashless, only plastic cards in use. Likewise, our government could decree that trees cannot be cut for making coffins. But first of all, of course, seeing that an alternative is freely available, tested and proved up to the job of holding a dead body for a couple of days

Worship fervour

The exposition of the Sacred Tooth Relic in the Dalada Maligawa, Kandy, is over. However, we do not know whether the consequences of the huge gathering of people in that already crowded and hemmed-in-by-mountains city are felt now. Maybe the authorities in Kandy did not expect such a pouring in of humanity to the Hill Capital. Maybe when President Dissanayaka voiced his opinion that an exposition would be good, he did not envisage such an influx of people to the city.

A friend said that the JVP Leader as Prez voiced his wish as a political gimmick. He said the JVP had hired buses and brought people to Kandy in droves, ignoring the fact it was bursting at the seams from day one onwards. Cass mentions these suppositions not believing them herself. But one fact emerged: an exposition of the Relic as was done recently cannot be repeated. Cass feels a solution would be to allocate days for the Provinces at the next exposition, province by province coming to Kandy, probably combining the Northern and Eastern. Provinces, where Buddhists are fewer in number.

Expositions at the Dalada Maligawa were much more frequent long ago, say up until the 1970s or so. Cass was born and bred in Kandy. Many were the expositions she recalls in the 1940s and 50s. Crowds were much less of course but the single queues that formed were perhaps the first she had seen. The Diyawadana Nilame then was always from a radala (aristocratic) family and was voted in by Kandyan Divisional Revenue Officers (DRO). Mother boasting two in the family got double passes to go straight into the inner chamber and watch the entire process of removal of jewellery and caskets until the final glass casket is revealed. I had to accompany her to the Maligawa but refused entrance to the inner sanctum. Much preferred by me was walking in a queue. Mother’s comment was that I lacked labeema. True!

The crowds, the adoration, the surely felt feeling that more the suffering, the greater the merit earned – pina, goes to show that for very many zeal exceeds piety. Yes, it’s good to venerate the Tooth Relic but the Buddha never wanted any veneration of himself or his remains after his death. He was a human being but with superior wisdom. insight, intelligence. He never wanted the fact that he was a human being to be forgotten since his teaching was to follow the Path he showed to end all suffering of repeated births and deaths. Cass admits she giggled, yes wickedly derisive, when women said they would now surely attain Nibbana having worshipped the Sacred Tooth. Zealousness outpacing sincere devotion; diminishing true sila or piety.

Hundred days of Trump’s reign

One may even term these past three months ‘Trump’s tumultuous dictatorship’.

He did his slow-motion dance before a huge celebrating crowd to announce that never in the history of the US of America has there been such a successful presidency; that he, Donald Trump, has shown most pluses and successes in his first 100 days than any other president in American history. Cass just muttered ‘Tell that to the Chinaman’ with double innuendo now. She cannot fathom how conceited, egotistic and self- believing this man is. And he is not merely boasting; Cass is sure he believes he is the greatest, while in his first quarter he has plunged international trade to the dumps; made life worse for most Americans, and almost caused an American and world recession.

Features

The truth will set us free – II

Lesson 2: Renewal begins with children

Timothy Snyder (55) maintained interaction with his two children (ten-year-old son and the younger daughter) while he was in a Florida hospital at the beginning of 2020. No doubt, his wife Marci Shore (53), also teaching history at Yale University then, helped this loving interaction between the father and his children. The children told him about their school work and inquired about his progress towards recovery. Snyder remembers how he kept thinking about his children even in his sickest moments. and finds fault with America for falling short of the standards reached by countries like Austria in infant and child health.

Of course, in fairness to America today (2025), it must be said that children, parents, and their health and welfare, and the family institution are receiving the highest recognition in the country, irrespective of untenable extremes of neoliberalism ideologies like wokeism and related lgbtqa+ and transgender sex change surgery issues, etc., as evident at least in the American domestic political domain. Elon Musk (53), Senior Advisor to US President Donald Trump (78), is often seen with his youngest son having a piggyback ride on his busy father’s shoulders even on state occasions; President Trump sometimes proudly shows off his nineteen-year-old son Barron accompanying him on the stage, the fresh young man stealing the show at his old father’s expense, especially among young voters. The youngish US Vice President J.D. Vance (40) and Usha Vance (39), his wife of Indian origin, were on a four-day visit (beginning April 21) to resurgent India recently with their three little children who, innocently unaware of and unconcerned about what was going on around them, endeared Americans to Indians, thereby greatly enhancing the efficacy of their parents’ diplomatic endeavour to strengthen bilateral bonds and economic and security cooperation between the two powerful nations. Musk and Trump are businessmen turned politicians, while the Vances have been lawyers. But all four are normal parents. Cynics might cavil at such ‘childish displays’ as advertising gimmicks for promoting the pro binary sex ideology perspective, where children are insensitively exploited as mascots for their propaganda. But a more sober judgement would be to view such high-profile demonstrations as indicating an emergent trend in America towards a return to healthy normalcy in its sex culture where parents with their own children form close knit stable family units that coalesce into a vibrant society.

Snyder recounts how well he and his wife Marci were treated as first-time parents in a public hospital in Vienna in Austria, where their son was born in 2009. They had to pay hardly anything by way of hospital fees. The Snyders ‘experienced a sense of what good health care felt like from inside: intimate and inexpensive’. Marci was given a ‘mother-child passport’, which was recognised at health facilities throughout Austria. When she entered any hospital or doctor’s office, she was asked to show the ‘passport’. The doctor or the nurse didn’t look at a screen to identify the mother and her child.

In Austria, according to Snyder, pregnant mothers close to delivery time are asked to come to the maternity hospital at water breaking (i.e., when the amniotic sac covering the foetus breaks) or when contractions occur at 20-minute intervals. In America, they are asked to wait longer until the contractions are only three or four minutes apart. So, in America, deliveries sometimes happen in the back seat of a car, putting both the babies and the mothers in danger. In Austria, again, the mother and the baby have to stay in hospital for 96 hours (4 days) after delivery, allowing time for the baby to have a good start, and for the mother to learn to breastfeed. The difference between America and Austria in this respect, Snyder says, is one between a logic of profit and a logic of life.

Even the general public in Austria are helpful towards parents with children. The institutions that helped the Snyders (as first-time parents) ‘from the public hospital to the public kindergarten to the public transport were an infrastructure of solidarity that helped people together, making them feel that at the end of the day they were not alone’, whereas in America, ‘birth is where our story about freedom dies. We never talk about how bringing new life into the world makes heroic individualism impossible’. (That is, doing everything alone, with little outside help, preserving one’s autonomy, is not possible in the real world)

This applies to children in their formative years, as well. A piece of wisdom Snyder offers is that ‘to be free involves having a sense of one’s own interests and of what one needs to fulfill them. Thinking about the constraints of life under pressure requires an ability to experience, name and regulate emotions’. But this freedom cannot be gained without help. That is the paradox of freedom as Snyder calls it; no one is free without help

Snyder distils into his critique of the unsatisfactoriness of the American healthcare system an important insight in respect of early childhood care: it is that ‘how children are treated when they are very young profoundly affects how they will live the rest of their lives. That is perhaps the most important thing that scientists have to teach us about health and freedom today’. Speech, thought and will emerge as infants and toddlers interact with other people. ‘We learn as very small children, if we ever learn, to recover from disappointment and to delay pleasure. …what allows these capacities to develop are relationships, play and choices’.

Snyder points out that providing good healthcare facilities for children leads eventually to a lower crime rate, functional democracy, and efficiency in decision making. He feels that emotional regulation is overlooked in America. There is no sufficient focus on the relationship between parents and children. The regrettable lapses in American health care affects children more negatively than for adults. Parents need to relate to their children in ways that promote their optimal physical, mental and ethical development is part of a good healthcare system. Healthy interaction between parents and children is of vital importance for the education of children. Probably, the situation in Sri Lanka may not be better than in America in view of, among other things, the economic hardships that parents inevitably have to face.

Children and young adults, particularly in suburban and rural areas, are a threatened species. Apart from the economic difficulties that their parents experience, restricting their ability to meet the cost of augmenting the education that the state provides free of charge, non-urban Sri Lankan children often suffer due to a lack of basic infrastructure facilities like good transport, proper school buildings, modern libraries and adequately equipped labs, internet facilities and easy accessibility to local and foreign online sources of learning and research.

Lesson 3: The truth will set us free

After a procedure done on his liver in the emergency room of an American hospital on December 29, 2019, Timothy Snyder was admitted to a room, where he spent the last days of the year and the first days of the next ‘raging and contemplating’. He had to share that room with a Chinese man with a number of afflictions. The Chinese didn’t know any English. So, a lot of ‘personal and medical information was communicated loudly, slowly and repeatedly’. The Chinese was senior to Snyder by fourteen years; he was in withdrawal from nicotine smoking and alcohol drinking after five decades of daily consumption of the two intoxicants. The two became mutually accommodating friends.

But Snyder suffered a lung infection due to close contact with the Chinese, who had himself succumbed to illness caused by a parasite ingested while eating raw fish on a previous visit to China, but got well later. However, Snyder recovered and left the hospital, after exchanging farewell messages with the friendly Chinese, who had to stay on further in hospital.

The latter, Snyder says, is an example of two ways that medicine can get to the truth: thinking along with the patient, focusing on their story, and searching for information through tests. His conclusion is that in early 2020, the federal government failed Americans in both ways. There was no sensible discussion of the history of pandemics, and no procedure to test for the new coronavirus. The sections of the National Security Council and the Department of Homeland Security meant to deal with epidemics, as well as a special unit in the Agency for International Development meant to predict epidemics had been disbanded. American health experts had been called back from the rest of the world. The last officer of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention assigned to China had been recalled to the US in July 2019, a few months before the epidemic broke out.

President Trump had overseen budget cuts for institutions looking after public health. The US surgeon general sang in a tweet on February 1, 2020: ‘Roses are red/Violets are blue/Risk is low for #coronavirus/But high for the flu’. Nero was fiddling while Rome was burning! As the year began, Americans were denied the basic knowledge necessary for making independent decisions of their own. President showed little anxiety about the steadily growing threat of the coronavirus. ‘It is going to disappear…like a miracle’. In effect they were creating a ‘news desert’. The media kept silent about the spreading pollution. Google and FB don’t carry news. They only raked in advertising revenues as usual.

But the disease was transmitted rapidly across the counties. The Covid death toll rose in leaps and bounds. ‘The seven American counties with the most Covid deaths would now rank among the top twenty countries. These are simple facts’. Snyder observes: ‘Since the truth sets you free, the people who oppress you resist the truth’. Historian Snyder refers to why British people have unkind memories of prime minister Neville Chamberlain because he tried to please the public in 1938 by falsely asserting that there was no need to go to war against Hitler. Winston Churchill earned their love and honour for having told them the unpleasant truth that they had to make war on the Nazi leader to stop him.

Snyder remembers reading (J.R.R. Tolkien’s) The Lord of the Rings to his son and daughter before he became ill. In that story Gandalf the wizard is a noble character with great power. He tells truths that people don’t want to hear. He is usually disliked as a bearer of bad news, and his advice is ignored. Although Gandalf is powerful, he cannot save the world by himself. He needs to build up a coalition by convincing others of the reality of a threat; but they won’t listen to him. Instead, out of ignorance, they look for an excuse for submission.That is human nature, but no way to be free. In frustration, Gandalf finally retorts that without knowledge, freedom has no chance.

Lesson 4: Doctors should be in charge

Snyder’s unexpected midnight admission to a hospital in Florida and two days stay there coincided with his mother’s birthday that year. So, he was unable to be with her on the occasion. The attention he got from the doctors was hurried and seemingly perfunctory, and it was hardly face-to-face. The longest time of fifteen minutes he saw a doctor was over Skype with a neurologist. Snyder thinks that the problem is not that doctors do not want to work with patients. They do work really hard, as people saw during the pandemic, risking their own health and even their lives in order to save others’ lives. The problem, according to Snyder, is that they have no say in what happens around them, but waste their time and energy pacifying greater powers. In America, doctors no longer have the authority that patients expect and need from them.

Readers, please remember that this was five years ago. The situation in America may have improved since, especially after the coronavirus pandemic took its toll and departed. The alleged mercenary bias of the American healthcare system largely caused by the profiteering Big Pharma, the insensitivity of the colluding political authorities, and the misinformation peddled by the media (particularly digital) that Snyder sharply criticizes in this book may have eased, too.

However, a little reflection will convince the intelligent readers that Timothy Snyder’s Four Lessons have great relevance to certain aspects of the deplorable situation in Sri Lanka today. This ad hoc review of mine of Snyder’s book, if read with a ‘comparative research’ oriented mind, will make the book look like a mirror held up to the prevailing reality there. (I have used a paperback edition of the book in my possession, issued by The Bodley Head, London, in 2020, in which year Snyder’s book containing his cogent case and powerful appeal for redress was first published.)

Concluded

by Rohana R. Wasala

(Continued from April 25, 2025)

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoLankan ‘snow-white’ monkeys become a magnet for tourists

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoNew Lankan HC to Australia assumes duties

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoPick My Pet wins Best Pet Boarding and Grooming Facilitator award

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoJapan-funded anti-corruption project launched again

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoKing Donald and the executive presidency

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoACHE Honoured as best institute for American-standard education

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoSethmi Premadasa youngest Sri Lankan to perform at world-renowned Musikverein in Vienna

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoNational Savings Bank appoints Ajith Akmeemana,Chief Financial Officer