Features

How smart is it to litigate to be proven right?

By Dhara Wijayatilake1

A disputant goes into court against another because he thinks he is right and the other is wrong and wants a court pronouncement to cement his position. After many years, huge expense, many consultations with Lawyers, many trips to the court house, postponed hearings, and even perhaps much emotional turmoil, a Judge delivers a judgment. One party is proven right and the other wrong, or the case may even be decided on a procedural matter with no determination as to who is right and who is wrong. Even the winner, if there is one is a loser. Today, there are options to litigation such as Mediation where the focus is not on being right, but on what each disputant needs and on reaching a settlement to satisfy those needs. It’s a process that is fast and cost effective. So, it’s a call to be smart – spend time and money to be right (litigation – where you may even end up being wrong) or spend much less time and much less money to satisfy needs (Mediation).

Delays in courts have reached ridiculous levels. Many Ministers of Justice over many years have attempted to reduce delays by “reforming” laws. The outcomes have not made a significant difference and the challenge to find solutions continue. One of the most comprehensive studies on Laws Delays in Sri Lanka was perhaps the one done by the “Laws Delays and Legal Culture Committee” headed by Justice R. S. Wanasundera, Judge of the Supreme Court. In its Report of October 1985 the Committee identified several causes for delays and submitted proposals to remedy them. The Report included a poignant observation that remains valid even today, ie. that in an adversarial system of justice such as ours, delays destroy justice, deterrence is lost, costs are increased, court resources are wasted and severe emotional hardship is inflicted upon litigants. In combination, these factors undermine the efficacy of the whole legal system, sapping its strength, vitality and even its integrity, and making the majority of litigants lose confidence. This observation remains valid even today. While substantive and procedural laws can be reformed in an attempt to eliminate delaying features, the legal culture which is a significant contributor can only be reformed through good practices that then constitute our legal culture. Here’s where we fail.

Laws delays is not a phenomenon that’s peculiar to Sri Lanka. It’s a problem confronting many jurisdictions across the globe. It’s this disillusionment with litigation which is rooted in the adversarial system, that has motivated a diversion to alternative methods of resolving disputes. The most popular Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) methods are Arbitration, Mediation and Negotiation. This article discusses Mediation which is accepted globally as an alternative that offers benefits that have proved to be meaningful.

Features of Mediation

There are many models of Mediation including Facilitative and Evaluative which are the most popular. In the 1960s, Facilitative Mediation flourished because of its marked difference in approach to conflict resolution and the resulting successes. Evaluative mediation is used by Mediators who are subject experts and offers an opinion on the strengths and weaknesses of the legal positions of the disputants leading to informed decision making by the disputants. This method is often used by judges in jurisdictions that provide for a settlement conference. This article discusses Facilitative Mediation which offers a process that’s unique in its features and is in complete contrast to litigation or Arbitration. Mediation evokes excitement because it’s speedy and cost effective, These virtues alone make a good case for opting for Mediation. There are others.

=It provides for party autonomy. Parties decide on the Mediators, the venue, the language of the mediation, the rules, and importantly, controls the outcome. No outside party sits in judgment over the dispute or how it should be settled.

=It’s informal but inspires trust. Parties sit with the Mediator and the other parties in an informal setting and engage in the process directly. They are provided ample space to speak of their concerns and participate fully while maintaining their dignity. Although there are no formalities as in a court of law, parties are required to conduct themselves in a disciplined manner. Parties are guided to move away from positions and focus on interests and needs instead.

=The procedural rules are simple and user friendly and are designed only to ensure responsible conduct. The process is not bogged down with procedural imperatives. There’s never a risk as prevails in litigation, that some flaw in complying with a procedural rule will get primacy over the core issues in the dispute, in determining the fate of the parties.

=It’s voluntary. The disputants use the option of mediation by choice and are free to walk out of a mediation at any time and are not obligated at any stage to stay in the process. This is so, even if reference to mediation is mandatory by law, based on the category of dispute and its monetary value. What is mandatory is to attempt a mediated settlement prior to proceeding to file action in a court of law.

= There’s no judgment of right vs wrong. It’s a process that seeks to find common ground to agree on a settlement that addresses the interests of both parties, and is not a process that evaluates legal entitlements although those can also be taken into account by parties when agreeing to a settlement.

=It adopts a completely non adversarial approach and therefore affords the opportunity for parties to repair fractured feelings, thus enabling an ongoing relationship.

=It’s confidential. This is an important feature of Mediation. Parties are required to sign agreement to maintain confidentiality with regard to all matters discussed. Parties agree not to divulge the substance of discussions at any other dispute resolution forum.

= The process is skillfully facilitated by a third party neutral, the Mediator. The Mediator controls the process using special skills and techniques and facilitates the disputants to reach an outcome that’s acceptable to them. The Mediator ensures that ground rules are followed to control emotions and avoid aggression during the sessions.

Neutrality of the Mediator is an important feature. The Mediator must at all times maintain independence and neutrality. If at any time, a disputant feels that this principle is breached, a mediation can be terminated.

Sri Lanka’s Mediation statutes

Mediation was first institutionalized with the enactment of the Mediation Boards Act, No. 72 of 1988 which incorporated all of the key features of Mediation. Mediation Boards now function in every Divisional Secretary’s area across the country. These have come to be known as “community Mediation Boards.” Subsequently, the Mediation (Special Categories of Disputes) Act, No. 21 of 2003 was enacted2 to provide for more specialized mediation services for certain identified categories of disputes.

The 1988 Act stipulates that certain categories of disputes must be mandatorily referred to Mediation, and also that certain disputes cannot be entertained by Community Mediation Boards.

Where reference to Mediation is mandatory, no action in respect of such a dispute can be instituted in or be entertained by a court of law unless Mediation has been unsuccessful and a certificate of non settlement from the Mediation Board is produced.

Disputes that must mandatorily be referred to Mediation are-

a) where the value of the dispute is below the monetary threshold set out in the Act, unless it’s one which gives rise to a cause of action set out in the Third Schedule to the Act.

In 1988 the monetary threshold was stipulated as Rs. 25,000/=. This has been amended from time to time and the current threshold introduced in 2016 is Rs, 500,000/=1.

The Third Schedule to the Act sets out fifteen categories of actions. These are actions in relation to disputes that were not considered suitable for settlement through community Mediation Boards.

b) where the dispute is in relation to an offence which is set out in the Second Schedule.

The Second Schedule sets out eighteen offences punishable under twenty six (26) sections of the Penal Code.

While mandatory reference to Mediation is not required in the case of disputes above Rs. 500,000/=, it is possible for the parties to submit the dispute for Mediation voluntarily, unless the dispute is one in respect of which an application for settlement cannot be entertained by a Mediation Board.

The categories of disputes that cannot be entertained by a Mediation Board, even if the value of the dispute is below Rs. 500,000/=, are the following –

where one party is the State; or

where one party is a public officer and the dispute relates to the recovery of property, money or other dues ; or

where the Attorney General has initiated proceedings in respect of an offence.

The Mediation (Special Categories of Disputes) Act, No. 21 of 2003-

The rationale for this Act was motivated by the reality that Mediation is the more appropriate method to resolve certain categories of disputes where positions based on strict legal rights and technicalities must give way to accord primacy to the needs of parties to address the underlying concerns. The challenge to reduce the litigation load in courts was also becoming a very serious one. The Act provides for the Minister to establish Mediation Boards to provide mediation services in respect of defined categories of disputes, in identified areas of the country. The category of dispute, the areas to which it will apply and the monetary threshold below which these disputes must mandatorily be referred to Mediation, are required to be set out in Orders made by the Minister1. An important statutory guideline that the Minister is required to consider to determine the categories of disputes is, “the need to provide for the meaningful resolution of disputes relating to social and economic issues.“1 It’s an important policy decision to be taken based on real needs of the people.

While the community Mediation Boards are manned by volunteers who are not required to have any specific educational qualifications, the distinguishing feature of the 2003 Act is that the Minister is required to prescribe by Regulation, the qualifications that a Mediator must possess having regard to the expertise required of Members, considering the nature of the categories of disputes that must be mediated. Different qualifications may be prescribed for different categories of disputes. The appointments are made by the same Mediation Boards Commission referred to in the 1988 Act.

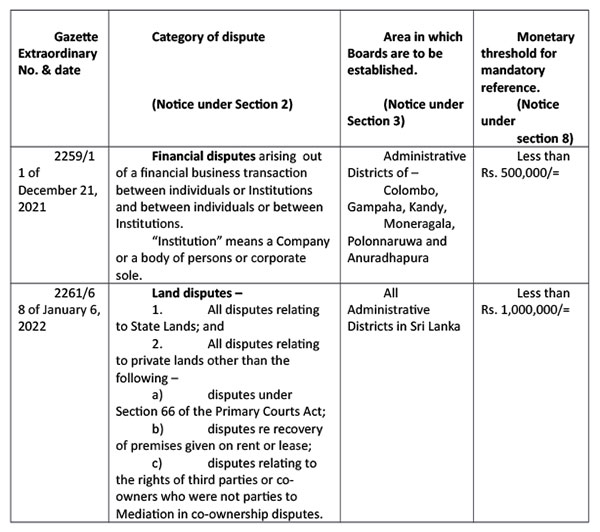

Mediation Boards were established under this Act in 2005 after the Tsunami of 2004 for the resolution of tsunami related disputes and in 2015 to resolve land disputes in the Administrative Districts in the North and East. It was accepted that Mediation was the more meaningful method to address land disputes that arose after the North East ethnic conflict. The Orders currently in force as at February 2022, provide for the following1 :

It is absolutely important that the persons who will function as Mediators are trained in the techniques and skills of mediation. Without proper, adequate and focussed training, the results will be disastrous and will negate the intentions of the Act since the success of mediation in conflict resolution is totally dependent on the intrinsic value of the techniques adopted. Mediation is not a process that can succeed if you simply have the ear of a patient listener.

The UN Convention on Mediation

Mediation has increased in acceptance over the years because of its benefits. It is this popularity and its increasing use in international commercial dispute resolution that inspired UNCITRAL’s Working Group on Dispute Settlement to address the need for a harmonious regime that will set standards for the cross-border enforcement of international settlement agreements resulting from mediation. As a result of its work, the Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation was adopted by the UN General Assembly (UNGA) on December 20, 2018,

The Preamble to the Convention recites that the Parties –

“recognize the value for international trade, of mediation as a method for settling commercial disputes in which the parties in dispute request a third person or persons to assist them in their attempt to settle the dispute amicably;

note that mediation is increasingly used in international and domestic commercial practice as an alternative to litigation;

considers that the use of mediation results in significant benefits, such as reducing the instances where a dispute leads to the termination of a commercial relationship, facilitating the administration of international transactions by commercial parties and producing savings in the administration of justice by States; and

are convinced that the establishment of a framework for international settlement agreements resulting from mediation that is acceptable to States with different legal, social and economic systems would contribute to the development of harmonious international economic relations “

The Convention opened for signature on August 7, 2019 in Singapore and Forty Six (46) countries including Sri Lanka became signatories on that same day. Popularly knows as the “Singapore Convention on Mediation”, it came into force on September 12, 2020. As at February, 2022 it has been signed by 55 countries and ratified by 9. Sri Lanka is now obligated to enact domestic legislation to give effect to the provisions of the Convention. UNCITRAL’s work on the Convention and its adoption by the UNGA, is evidence of the the global acceptance of Mediation to resolve commercial disputes.

The CCC- ICLP International ADR Center of Sri Lanka (IADRC)

In 2018, the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce (CCC) and the Institute for the Development of Commercial Law and Practice (ICLP) in a joint venture, incorporated a not for profit company and established a new Center, the CCC-ICLP International ADR Center (IADRC) to provide ADR services. It was a response to the need of the business community for more efficient dispute resolution. The novelty of the new Center is that it offers mediation services in addition to arbitration.

Both Institutions were aware of the global trends that favored ADR and the successes of Regional Centers. The Hong Kong International Arbitration Center (HKIAC) established in 1985, the Singapore Mediation Center (SMC) launched in 1997, the Indian Institute of Arbitration and Mediation (IIAM) established in 2001, the International ADR Center of the Indian Merchants Chamber (IIMC) established in 2015 and the Malaysian Mediation Center (MMC) established in 1999 under the auspices of the Bar Council of Malaysia, offered inspiration. These centers offered services that included Arbitration and Mediation. The Singapore Mediation Center states that, as at Feb 2022, it has mediated 5,200 matters worth over $10 billion since its launch. The rate of successful mediations is stated to be 70% with 90% of those having been settled in one day! The high rate of success can be attributed to the skill and competence and the professionalism of the Mediators. Compliance with the mediation process and using the special skills and techniques are key to achieving good outcomes and hence the absolute need for training.

The IADRC launched its Arbitration and Mediation Rules in April 2021 and has trained Mediators and Arbitrators who are available to provide services. The Arbitration Rules of the Center seek to eliminate some of the common causes for delay. It’s the only Center that offers institutionalized Mediation for commercial dispute resolution. Arbitration and Mediation services can be administered in compliance with these Rules of the Center, or the UNCITRAL Rules, or any others that may be adopted on an ad hoc basis.

The Mediation Rules of the IADRC

The CCC-ICLP Mediation Rules incorporate all the internationally recognized standards that are known to define the Mediation process. The Rules provide for the following-

To commence the Mediation, an application (a “Request for Mediation”) must be made to the Center either by one party or jointly by all disputing parties, requesting Mediation services for the settlement of the dispute.

After completing preliminary administrative steps such as obtaining, where appropriate, the consent of all parties to pursue Mediation, the parties are required to sign the “Agreement to Mediate”. This Agreement includes an obligation to “abide by and comply with the Mediation Rules of the Center or other Rules that have been agreed to.”

The language of the Mediation will be as agreed to, by the parties.

The next step is to appoint a Mediator or a panel of Mediators. The disputing parties have the discretion to nominate a Mediator from among those accredited by the Center or from outside of that list. Usually, a Mediation will be handled by a single Mediator. However, a panel could be appointed if so desired, where there are complex issues in a dispute.

Importantly, the Mediator has to be independent, impartial and neutral throughout the process. Several safeguards are included to ensure compliance with this principle.

The Mediation sessions then commence. The Mediator manages the process and will, for this purpose convene sessions on dates and times agreed to by the parties, at a neutral venue.

The process will commence with a joint session where all parties are present. The Mediator will explain the principles that apply and explain the process. Thereafter the Mediator will decide when to have joint sessions with all parties, and individual sessions (called a “caucus”) with each party.

At these sessions, the parties have the opportunity to discuss the matters in dispute from their own perspective. The statements, disclosures and proposals made at a Mediation are maintained in absolute confidence and are made without prejudice. This principle provides the confidence to disputing parties that nothing said can be used in any other dispute resolution process or other forum. The Mediator and the parties cannot be compelled to give evidence as to any matters disclosed at the Mediation in a court of law.

The Rules set out the obligations of the parties – attendance at the sessions in person and in the case of corporate entities attendance through a representative who is given full authority to sign off on a Settlement Agreement; compliance with the rule on confidentiality; full and honest disclosure of matters material to the dispute.

Parties are not entitled to legal representation at the sessions but may call in a Lawyer for the sole purpose of obtaining advice. However, a Lawyer who is a full time employee of a corporate is not excluded from participating at the sessions on behalf of a corporate entity.

During these sessions, a Mediator will not give directions or instructions on how to settle the dispute. The Mediator will however question the parties in a non coercive manner to help them reach a new understanding of the issues in dispute and of the concerns of the other party.

A Mediation is terminated either with an agreement to settle or with an agreement that no settlement is possible.

Where there is an agreement to settle, the Mediator is required to explain to the parties the terms and conditions of the settlement and the obligations that each party is assuming under the agreement. A settlement Agreement will be set in writing and signed by the parties and the Mediator. This is an agreement that binds the parties as any other agreement, and each party has a legal obligation to honour its terms and conditions.

Where the Mediator determines that continuing the Mediation is futile since it’s unlikely to result in a settlement considering the progress of the Mediation, or where a party informs that it wishes to withdraw from a Mediation, the Mediation will be terminated.

In either event, all the documents submitted to the Center by each party will be returned.

In normal circumstances a mediated agreement should stand the test of time since many steps have been taken to ensure it’s sustainability. However, the Rules provide for an application to be made to revise or revoke an Agreement on very limited grounds, ie. On the grounds that a) the terms were agreed to, without a proper appreciation of the obligations; or b) circumstances have arisen that prevent a party honoring the obligations; or c) that there was bias on the part of the Mediator. The last ground is most unlikely given the several steps that are required to be taken to ensure impartiality. However, this ground is included as a principle of good governance since it’s a vital feature of Mediation. An application to revise or revoke will be inquired into by the Center and a settlement will be attempted in compliance with the same principles that apply to a Mediation.

Mediation is not an expensive process. However there are fees to be paid. The Fees for a Mediation include Administration fees as well as fees for the Mediator/s. The fees are prescribed by the Center in a Fee Schedule and will be a predetermined sum which will be made known to the parties prior to the commencement of the Mediation. There will be no surprises.

Conclusion

Mediation is not the most appropriate method of dispute resolution for all categories of disputes. That’s accepted. Even with the twin evils of delay and expense certain causes of action need to be determined by a court of law. Mediation however, has gained global recognition as the better method for many kinds of disputes ranging from family and workplace disputes to construction and commercial disputes.

Given the potential to be speedy and cost effective, and the high level of user satisfaction, the services provided by the CCC-ICLP IADR Center will no doubt improve the commercial dispute resolution landscape in Sri Lanka. It will also contribute to improve Sri Lanka’s performance in the contract enforcement indicator in the Doing Business rankings. The enactment of domestic legislation to enable the enforcement of international mediated settlement agreements in line with the Singapore Convention will also certainly enhance Sri Lanka’s efforts to attract foreign investors. The slogan “Mediate, don’t litigate” is gaining in popularity given the reality that it’s not always smart to litigate to be right.

Features

Maduro abduction marks dangerous aggravation of ‘world disorder’

The abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by US special forces on January 3rd and his coercive conveying to the US to stand trial over a number of allegations leveled against him by the Trump administration marks a dangerous degeneration of prevailing ‘world disorder’. While some cardinal principles in International Law have been blatantly violated by the US in the course of the operation the fallout for the world from the exceptionally sensational VVIP abduction could be grave.

The abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by US special forces on January 3rd and his coercive conveying to the US to stand trial over a number of allegations leveled against him by the Trump administration marks a dangerous degeneration of prevailing ‘world disorder’. While some cardinal principles in International Law have been blatantly violated by the US in the course of the operation the fallout for the world from the exceptionally sensational VVIP abduction could be grave.

Although controversial US military interventions the world over are not ‘news’ any longer, the abduction and hustling away of a head of government, seen as an enemy of the US, to stand trial on the latter soil amounts to a heavy-handed and arrogant rejection of the foundational principles of international law and order. It would seem, for instance, that the concept of national sovereignty is no longer applicable to the way in which the world’s foremost powers relate to the rest of the international community. Might is indeed right for the likes of the US and the Trump administration in particular is adamant in driving this point home to the world.

Chief spokesmen for the Trump administration have been at pains to point out that the abduction is not at variance with national security related provisions of the US Constitution. These provisions apparently bestow on the US President wide powers to protect US security and stability through courses of action that are seen as essential to further these ends but the fact is that International Law has been brazenly violated in the process in the Venezuelan case.

To be sure, this is not the first occasion on which a head of government has been abducted by US special forces in post-World War Two times and made to stand trial in the US, since such a development occurred in Panama in 1989, but the consequences for the world could be doubly grave as a result of such actions, considering the mounting ‘disorder’ confronting the world community.

Those sections opposed to the Maduro abduction in the US would do well to from now on seek ways of reconciling national security-related provisions in the US Constitution with the country’s wider international commitment to uphold international peace and law and order. No ambiguities could be permitted on this score.

While the arbitrary military action undertaken by the US to further its narrow interests at whatever cost calls for criticism, it would be only fair to point out that the US is not the only big power which has thus dangerously eroded the authority of International Law in recent times. Russia, for example, did just that when it violated the sovereignty of Ukraine by invading it two or more years ago on some nebulous, unconvincing grounds. Consequently, the Ukraine crisis too poses a grave threat to international peace.

It is relevant to mention in this connection that authoritarian rulers who hope to rule their countries in perpetuity as it were, usually end up, sooner rather than later, being a blight on their people. This is on account of the fact that they prove a major obstacle to the implementation of the democratic process which alone holds out the promise of the prgressive empowerment of the people, whereas authoritarian rulers prefer to rule with an iron fist with a fixation about self-empowerment.

Nevertheless, regime-change, wherever it may occur, is a matter for the public concerned. In a functional democracy, it is the people, and the people only, who ‘make or break’ governments. From this viewpoint, Russia and Venezuela are most lacking. But externally induced, militarily mediated change is a gross abnormality in the world or democracy, which deserves decrying.

By way of damage control, the US could take the initiative to ensure that the democratic process, read as the full empowerment of ordinary people, takes hold in Venezuela. In this manner the US could help in stemming some of the destructive fallout from its abduction operation. Any attempts by the US to take possession of the national wealth of Venezuela at this juncture are bound to earn for it the condemnation of democratic opinion the world over.

Likewise, the US needs to exert all its influence to ensure that the rights of ordinary Ukrainians are protected. It will need to ensure this while exploring ways of stopping further incursions into Ukrainian territory by Russia’s invading forces. It will need to do this in collaboration with the EU which is putting its best foot forward to end the Ukraine blood-letting.

Meanwhile, the repercussions that the Maduro abduction could have on the global South would need to be watched with some concern by the international community. Here too the EU could prove a positive influence since it is doubtful whether the UN would be enabled by the big powers to carry out the responsibilities that devolve on it with the required effectiveness.

What needs to be specifically watched is the ‘copycat effect’ that could manifest among those less democratically inclined Southern rulers who would be inspired by the Trump administration to take the law into their hands, so to speak, and act with callous disregard for the sovereign rights of their smaller and more vulnerable neighbours.

Democratic opinion the world over would need to think of systems of checks and balances that could contain such power abuse by Southern autocratic rulers in particular. The UN and democracy-supportive organizations, such as the EU, could prove suitable partners in these efforts.

All in all it is international lawlessness that needs managing effectively from now on. If President Trump carries out his threat to over-run other countries as well in the manner in which he ran rough-shod over Venezuela, there is unlikely to remain even a semblance of international order, considering that anarchy would be receiving a strong fillip from the US, ‘The World’s Mightiest Democracy’.

What is also of note is that identity politics in particularly the South would be unprecedentedly energized. The narrative that ‘the Great Satan’ is running amok would win considerable validity among the theocracies of the Middle East and set the stage for a resurgence of religious fanaticism and invigorated armed resistance to the US. The Trump administration needs to stop in its tracks and weigh the pros and cons of its current foreign policy initiatives.

Features

Pure Christmas magic and joy at British School

The British School in Colombo (BSC) hosted its Annual Christmas Carnival 2025, ‘Gingerbread Wonderland’, which was a huge success, with the students themseles in the spotlight, managing stalls and volunteering.

The British School in Colombo (BSC) hosted its Annual Christmas Carnival 2025, ‘Gingerbread Wonderland’, which was a huge success, with the students themseles in the spotlight, managing stalls and volunteering.

The event, organised by the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA), featured a variety of activities, including: Games and rides for all ages, Food stalls offering delicious treats, Drinks and refreshments, Trade booths showcasing local products, and Live music and entertainment.

The carnival was held at the school premises, providing a fun and festive atmosphere for students, parents, and the community to enjoy.

The halls of the BSC were filled with pure Christmas magic and joy with the students and the staff putting on a tremendous display.

Among the highlights was the dazzling fashion show with the students doing the needful, and they were very impressive.

The students themselves were eagerly looking forward to displaying their modelling technique and, I’m told, they enjoyed the moment they had to step on the ramp.

The event supported communities affected by the recent floods, with surplus proceeds going to flood-relief efforts.

Features

Glowing younger looking skin

Hi! This week I’m giving you some beauty tips so that you could look forward to enjoying 2026 with a glowing younger looking skin.

Hi! This week I’m giving you some beauty tips so that you could look forward to enjoying 2026 with a glowing younger looking skin.

Face wash for natural beauty

* Avocado:

Take the pulp, make a paste of it and apply on your face. Leave it on for five minutes and then wash it with normal water.

* Cucumber:

Just rub some cucumber slices on your face for 02-03 minutes to cleanse the oil naturally. Wash off with plain water.

* Buttermilk:

Apply all over your face and leave it to dry, then wash it with normal water (works for mixed to oily skin).

Face scrub for natural beauty

Take 01-02 strawberries, 02 pieces of kiwis or 02 cubes of watermelons. Mash any single fruit and apply on your face. Then massage or scrub it slowly for at least 3-5 minutes in circular motions. Then wash it thoroughly with normal or cold water. You can make use of different fruits during different seasons, and see what suits you best! Follow with a natural face mask.

Face Masks

* Papaya and Honey:

Take two pieces of papaya (peeled) and mash them to make a paste. Apply evenly on your face and leave it for 30 minutes and then wash it with cold water.

Papaya is just not a fruit but one of the best natural remedies for good health and glowing younger looking skin. It also helps in reducing pimples and scars. You can also add honey (optional) to the mixture which helps massage and makes your skin glow.

* Banana:

Put a few slices of banana, 01 teaspoon of honey (optional), in a bowl, and mash them nicely. Apply on your face, and massage it gently all over the face for at least 05 minutes. Then wash it off with normal water. For an instant glow on your face, this facemask is a great idea to try!

* Carrot:

Make a paste using 01 carrot (steamed) by mixing it with milk or honey and apply on your face and neck evenly. Let it dry for 15-20 minutes and then wash it with cold water. Carrots work really well for your skin as they have many vitamins and minerals, which give instant shine and younger-looking skin.

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoInterception of SL fishing craft by Seychelles: Trawler owners demand international investigation

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoBroad support emerges for Faiszer’s sweeping proposals on long- delayed divorce and personal law reforms

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoPrivate airline crew member nabbed with contraband gold

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoPrez seeks Harsha’s help to address CC’s concerns over appointment of AG

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoGovt. exploring possibility of converting EPF benefits into private sector pensions

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoHealth Minister sends letter of demand for one billion rupees in damages

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoEducational reforms under the NPP government

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoPharmaceuticals, deaths, and work ethics