Midweek Review

Vignettes of the Open-Air Theatre

by Prof. K. N. O. Dharmadasa

It is indisputably The Open-Air Theatre – the first of its kind in the country and the most well-known. There indeed are some other similar constructions, like the one at Vihara Maha Devi Park, Colombo. But when theatre lovers talk of ‘the Open-Air Theatre’, the reference is unmistakably to the Open-Air Theatre in the ‘University Park’, Peradeniya. Incidentally, the appellation ‘University Park’ was a creation of Sir Ivor Jennings, the Founder Vice Chancellor of the University. The area where the university buildings were located was known by this name. Sir Ivor was so enamoured of the site that he called it ‘one of the most beautiful environments in the world” (his autobiography The Road to Peradeniya,198). His Annual Reports usually had a sub-section titled ‘University Park’; he reported on the building programme and the landscaping, etc. Coming back to the Open-Air Theatre, which was constructed three years after he left in January 1955, undoubtedly adds to the beauty of the whole landscape – a good example of how a tastefully constructed structure which blends with the surroundings can enhance the natural beauty of a place.

The conception

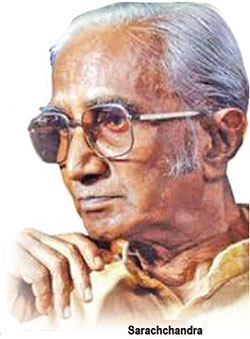

The Open-Air Theatre was ceremonially declared open in early 1958. The first drama staged there was Sarchchandra’s epoch making Maname. As all theatre lovers know, the initial staging of Maname was on Nov. 3, 1956 at the Lionel Wendt Theatre in Colombo and nearly 100 performances would have taken place during the 15 or so months before it was staged at the newly constructed Open-Air Theatre in Peradeniya. Prof. Sarachchandra in his Memoirs, Pin Ethi Sarasavi Waramak Denne, (published in 1985) gives a detailed account of the founding of the Open-Air Theatre, which aptly bears his name today.

Maname had already been staged and the first accolade had come from an unusual quarter. Regi Siriwardene, a highly respected critic and journalist attached to the Lake House Group of Newspapers called it “the finest thing I have seen on the Sinhalese stage” (Ceylon Daily News, Nov. 5) Many shows followed in Colombo, Kandy and other cities and several other writers to the English newspapers showered praise on this remarkable achievement as exemplifying what the national theatrical form could be. But the Sinhalese newspapers remained silent for quite some time and Sarachchandra kept wondering why it was so. “Was it due to the habitual antipathy towards the University by most of the journalists or was it because they failed to understand what Maname signified?” But the breakthrough came eventually. Sri Chandraratne Manavasinghe, the highly respected writer and journalist attached to the editorial staff of the daily Lankadeepa, wrote a highly complimentary review of the play in his daily column Waga –Tuga and called it an Abhiranga (super-drama).

Sarachchandra with his vast experience in Oriental and Occidental theatre traditions, believed that “a super-performance of Maname could be done, not on a proscenium stage which was meant for staging naturalistic plays, but on a circular stage, (ranga madala)”. And he was on the lookout for such a place … amidst the hilly terrain of Peradeniya. He adds:

“Those days I was residing in one of the three bungalows on Sanghamitta Hill. While descending the hill and walking towards the Arts Block, I noticed a piece of land concave in shape, like a part of a broken clay pot. This was a terraced paddy field which had been abandoned and was overgrown with weeds. At the bottom of the land was a flat space. Although I had been passing that place daily it was only after I started thinking of an open-air theatre that it struck me as a suitable location for what is known as an Amphitheatre – an auditorium with a stage. The space at the bottom could be used as a stage and the audience could sit in the terraces” (p. 209)

Acoustics

Sarachchandra was not prepared to rush into conclusions. Although the land appeared suitable in appearance, there was a crucial consideration when it came to an open-air theatre. “It was essential,” he adds. “To find out what the acoustics of this place was like for theatre performance. One evening I went there with a group of students. I think Gunasena Galappaththi was one of them. I placed several of them in various places in the pit and made them talk and sing. Then I realized that it was a place with natural amplification of sound. The Epidorus Amphitheatre in Greece came to my mind. If you stand anywhere and strike a match you will be able to hear it. (p.210).

Sarachchandra was not prepared to rush into conclusions. Although the land appeared suitable in appearance, there was a crucial consideration when it came to an open-air theatre. “It was essential,” he adds. “To find out what the acoustics of this place was like for theatre performance. One evening I went there with a group of students. I think Gunasena Galappaththi was one of them. I placed several of them in various places in the pit and made them talk and sing. Then I realized that it was a place with natural amplification of sound. The Epidorus Amphitheatre in Greece came to my mind. If you stand anywhere and strike a match you will be able to hear it. (p.210).

Now the problem was that of the logistics. At this time (1956-7) Sarachchandra was only a lecturer. He had no ‘clout’ to order officials in the administration. Of course, his fame and prestige were growing rapidly and by 1960 a special Chair of Sinhala was created for him, which was the first such occasion in the history of the University. But that is anticipating events. We resume the story of the construction of the OAT as narrated by Sarachchandra himself. Sarachchandra says:

“I had no power to give orders to the Works Department or to the Administrative Section. That could be done only by the Vice Chancellor or the Registrar. The expenses involved in constructing even an amphitheatre at the site I mentioned would be minimal. What had to be done was cutting and removing the weeds on the terraces, constructing in cement a circular stage at the bottom and putting up a cadjan shed behind it.” (pp. 210-11)

Now, the dilemma Sarachchandra was faced with was whether or not the Vice Chancellor would accept his proposal to construct an open-air theatre. Sarachchandra’s estimation of the Vice Chancellor Sir Nicholas Attygalle was not at all complimentary. “Like most people of the English-speaking upper class,” says Sarachchandra,

“He was completely devoid of any taste for the arts (kalaa vihiina). Although he was a Professor in the Faculty of Medicine before becoming Vice Chancellor, his range of knowledge was small (alpasruta). He did not have even a modicum of interest on theatre, literature, music, etc. I do not know whether he had read any other book outside the field of medicine.” (p.211).

For the present-day reader, I have to give an explanation. Without digressing too far it needs be noted that during the Attygalle phase of the University administration, there was a sharp division in the academic staff as pro-Attydalle and anti-Attygalle, and that was due largely to the dictatorial administrative style of the Vice Chancellor. It is clear where Sarachchandra stood in this division. In any case Prof. Attygalle had not displayed any interest in the arts. And the problem then was how to get the approval of a man like that for the construction of an open-air theatre. Then the miracle happened once again.

The Vice Chancellor came to know about Maname under fortuitous if not trivial circumstances. Continues Sarachchandra, “He came to know for the first time that a play named Maname had been created by a person named Sarachchandra, who was on his staff and that it was winning accolades in the country, from a group of lecturers who used to sit before his table daily, rumour-mongering and engaging in empty prattle. It was difficult for Mr. Attygalle, who had never seen a play, to understand what Maname was. He did not want to understand either. But because of the persuasions, he summoned me and asked me what this wondrous thing I had done was about which he had heard so much.” (p.211)

Sarachchandra now had to be humble. “I told him it was not a big miracle, but the production of a play. ‘Then why are they praising it so much’ he asked ‘and telling me I should see it somehow?” Next came the crucial question “Can it be shown in the University?” This created the opening Sarachchandra was looking for.

“I told him that there is no suitable theatre in the University where it could be shown. ‘But would it be possible,’ Then I asked, ‘whether such and such a place could be prepared for the purpose?’ He summoned the officers immediately and ordered them to construct without delay an open-air theatre on the site I had mentioned.” (p.211)

Sarachchandra then describes in humorous Sinhala how the officials set about their job and finished it in no time:

“The officers bent themselves double and treble, ran there, cut down the bush, pounded the ground, got a pretty circular stage made in cement, got a cadjan shed put up and created an amphitheatre in two or three days.” (p.211)

Sarachchandra’s narration about the opening of the Open-Air Theatre is quite informative, albeit with a touch of humour:

“On that day was presented the first ‘performance on orders’ (agnapita rangaya) of Maname before an audience which consisted of the Vice Chancellor, some members of the staff, Mr. Kilpatrick of the Rockefeller Foundation, the students and village folk coming from the neighbourhood. That was the day the Open-Air Theatre in Peradeniya was born. Maname came into being on 3rd November, 1956. It was performed in an ideal atmosphere, without damaging the traditional Nadagam style, at the Open-Air Theatre on a night of either February or March 1958 ((p. 212).

Mr. Kilpatrick referred to here is the Rockefeller Foundation representative who, after reading Sarachchandra’s well researched The Sinhalese Folk Play (1952) had granted him a travelling scholarship some years ago, to study theatre in any country he wished, which eventually enabled him to see the Japanese Kabuki giving him the clue to bring a traditional folk theatre on modern stage. Let us get back again to our discussion about the Peradeniya Open Air Theatre.

Improvements

During the early days the ‘seating’ terraces were levelled earth with trimmed grass. As the location, an abandoned paddy field with a running stream in the vicinity was damp the whole year round, it was a good breeding ground for leeches. During the days when plays were being performed, the leeches had a gala time. I myself remember my first experience of watching a play there, back in my first year 1959, Dayanada Gunawardena’s Parassa. There was a blood patch on my trousers and it was no easy task stopping the blood flow because it is said leeches inject their saliva, which prevents blood-clotting! Eventually, however, the terraces came to be constructed in granite and the leach population dwindled although one finds a stray leech climbing up one’s legs if one were to stand on the grass. Another casualty of the granite and cement intrusion was the lushly grown Tabubia Rosea tree which used to spread a carpet of light pink flowers on the terraces during the blooming season. Most probably its roots were suffocated by the cement construction.

The original Green Room, which was a cadjan shed as described by Sarachchandra, later came to be a Takaran shed with walls and roof made of galvanized sheets. It was painted in Green! Anyway, in the 1990s when I was the Chairman of the Arts Council, we managed to get a permanent Green Room constructed during the period 1991-92. I gratefully acknowledge the support we got from the Vice Chancellors Prof. Lakshman Jayatilaka and Prof. J. M. Gunadasa for these improvements. It was on March 24, 1993 that we named the theatre as Sarachchandra Elimahan Ranga Pitaya in honour of the man who had done so much for the Sri Lankan drama. I remember him attending the naming ceremony (again with a performance of Maname) and rising from his seat in the front row, facing the audience acknowledging the cheering of the massive crowd with hands clasped in Namaskara. He left us three years later on 16 August 1996.

An event highly significant in the annals of Sinhala theatre is the first staging of Sinhabahu on 31 August, 1961 at the Open-Air Theatre. There was a slight drizzle at the start of the performance which stopped after some time. I remember sitting on the damp grass watching the play on that memorable night. Fifty years later, on 28 November 2011, we were able to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of this play at the same venue, although we badly missed our beloved Guru. Special mention should be made of the patronage we received from the Vice Chancellor, Prof. S.B. Abeykoon, who made arrangements to show the play free of charge. Incidentally, he hails from Uda Peradeniya and has told us how as a child he had watched shows at the OAT seated on his father’s lap!

Drama Festivals

The most important annual event in the Open-Air Theatre was the Annual Drama Festival. In the good old days before the university calendar got disrupted, the Drama Festival was held in mid or the last week of January. This was the beginning of the third Term which consisted of 10 weeks of teaching and the examinations were scheduled for the last two weeks of March. January was selected because it was normally a dry period with no rains to disrupt the shows.

here would be a slight drizzle as the festival begins. Normally, the festival lasts seven or eight days and two invariable items would be Maname and later, Sinhabahu. when that university ‘term system’ got severely disrupted, the drama festivals came to be held in different periods, even during rainy seasons. One of the indelible memories I have of the OAT is of a show in the 1990s, when the packed audience sat there with rapt attention in the pouring rain.

When the festival is on, there is a festive atmosphere in the area. When the evening falls, people start gathering and various itinerant traders come, vendors of gram, peanuts, sara vita and even balloon vendors because sometimes parents come there with their children. I forgot to mention that this is not a mere university drama festival but a drama festival for the whole vicinity. People from Uda Peradeniya, Hidagala as well as other adjoining villages throng to the Open-Air Theatre during the festival.

Acid Test

There is a belief among theatre lovers in Sri Lanka that if a play could be staged at the Open-Air Theatre and come off unscathed that would be the best touchstone for ascertaining its success. It is difficult to explain the origins of this belief. With my experience from 1959 onwards, I can say that in those early days there was no unsuccessful play as such. It could be that all the plays staged there were good plays, carefully selected by the Arts Council, which managed the Annual Drama Festival. But in the 1970s, there were three unfortunate incidents, all of them involving plays by leading dramatists in the country, where the jeering by the crowd became unmanageable and the performances had to be abandoned. The first instance, if my memory is correct, was the play Sarana Siyot Se Putuni Hamba Yana by Henry Jayasena. The second, I think was Bak Maha Akunu by Dayananda Gunawardena. And the third was Cherry Watta by Somalatha Subasinghe. If my memory is correct, the failure of the first and the last mentioned, Sarana Siyot Se…and Cherry Watta were due to their lack of dramatic concentration and long spells of dialogue which tired the audience. In the case of Bak MahaAkunu what provoked the jeering was the over enthusiasm of the actor who played the role of the servant Jason. He got carried away in his diatribe against his master, the Mudalituma, who was making advances to his beloved Pabulina . He came on stage with sarong half tucked up, and uttered something that just fell short of a four-letter word and the audience protested immediately. The furore was uncontrollable and the show had to be abandoned. Possibly, these early experiences led to the belief that a show at the OAT is an acid test for the success for a play. At the same time, it needs be added that the two “failed” plays, Sarana Siyot Se and Cherry Watta were plays not quite suitable for an open-air theatre. But this leads to a theoretical problem which needs be addressed separately. The three incidents mentioned were sad occasions as all three dramatists involved were people dedicated to their vocation. Furthermore, Dayananda and Somalatha were respected alumni of the Peradeniya University.

It needs mention that that not all dramatists were prepared to take these judgments of the OAT audience lying down. I remember two incidents, both in the 1980s when the dramatists came on stage and challenged the jeering audience. One instance was when Namel Weeramuni, who was giving a performance of his Nettukkari, where he himself was playing a leading role. Incidentally, he himself is an alumnus of Peradeniya of the period when the OAT was constructed and he would have been thoroughly annoyed at this behaviour of the campus denizens of a later period. He came on stage in his costume and addressed the audience telling them that it was with great difficulty that anybody produces a drama and it should not be treated with such disrespect. Whoever did not like the play, could leave the audience allowing those who wished to stay back, watch the play. The shouting died down after some time and the play was resumed. The other incident involved Solomon Fonseka, who had won accolades all round for his star performance in Dayananda Gumawardena’s Nari Bena, some years back. Since then he had studied the art of theatre in a European university and obtained a Doctorate. This time he had produced his own play and was staging it in the OAT. For some reason which I forget, the audience became restive and started hooting. Solomon stopped the show, sent the other actors to the Green Room and addressed the audience in a defiant tone: “You fellows (umbala) call yourself educated. But what kind of education do you have if you are not civilized enough to behave yourself in a theatre? If someone does not like a play he can walk out and allow those who want to watch it, do so.” That worked. And the audience became quiet allowing the show to continue.

PS The reader would have noticed that I have refrained from using the trivial term “wala” which has come into much use in referring to this theatre. That is because it demeans the stature of this special theatre in our country.

Midweek Review

A look back at now mostly forgotten Eelam war in the aftermath of Kashmir massacre

In the aftermath of the Pahalgam massacre, Pakistan offered to cooperate in what it called a neutral investigation. But India never regretted the

catastrophic results of its intervention in Sri Lanka that led to the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi in May 1991, over a year after India pulled out its Army

from NE, Sri Lanka

In a telephone call to Indian Premier Narendra Modi, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake condemned the massacre of 26 civilians – 25 Indians and one Nepali – at Pahalgam, in the Indian controlled Kashmir, on April 22.

President Dissanayake expressed his condolences and reaffirmed, what the President’s Media Division (PMD) called, Sri Lanka’s unwavering solidarity and brotherhood with the people of India.

Having described the massacre as a terrorist attack, New Delhi found fault with Pakistan for the incident. Pakistan was accused of backing a previously unknown group, identified as Kashmir Resistance.

The Indian media have quoted Indian security agencies as having said that Kashmir Resistance is a front for Pakistan-based terrorist groups, Lashkar-e-Taiba and Hizbul Mujahideen fighting Indian rule in Kashmir. Pakistan says it only provides moral and diplomatic support.

Pakistan has denied its involvement in the Pahalgam attack. A section of the Indian media, and some experts, have compared the Pahalgam attack with the coordinated raids carried out by Hamas on southern Israel, in early October 2023.

President Dissanayake called Premier Modi on the afternoon of April 25, three days after the Pahalgam attack. The PMD quoted Dissanayake as having reiterated Sri Lanka’s firm stance against terrorism in all its forms, regardless of where it occurred in the world, in a 15-minute call.

Modi cut short his visit to Saudi Arabia as India took a series of measures against Pakistan. Indian actions included suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) governing water sharing of six rivers in the Indus basin between the two countries. The agreement that had been finalised way back in 1960 survived three major wars in 1965, 1971 and 1999.

One-time Pentagon official Michael Rubin, having likened the Pahalgam attack to a targeted strike on civilians, has urged India to adopt an Israel-style retaliation, targeting Pakistan, but not realising that both are nuclear armed.

Soon after the Hamas raid some interested parties compared Sri Lanka’s war against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), and the ongoing Israel war on Gaza.

The latest incident in Indian-controlled Kashmir, and Gaza genocide, cannot be compared under any circumstances. Therefore, suggestions that India adopt Israel-style retaliation against Pakistan do not hold water. Also, Sri Lanka’s war against the LTTE that was brought to a successful conclusion in May 2009 cannot be compared with the conflict Israel is involved in.

Sri Lanka can easily relate to the victims of the Pahalgam attack as a victim of separatist terrorism that bled the country for nearly 30 years. India, however, never bothered to express regret over causing terrorism here.

Indian-sponsored terror projects brought Sri Lanka to its knees before President JRJ made an attempt to eradicate the LTTE in May-June 1987. JRJ resorted to ‘Operation Liberation’ after Indian mediated talks failed to end the conflict. Having forced Sri Lanka to call off the largest-ever ground offensive undertaken at that time with the hope of routing the LTTE in Vadamarachchi, the home turf of Velupillai Prabhakaran, followed by India deploying its Mi 17s on July 24, 1987, to rescue the Tiger Supremo, his wife, two children and several of his close associates – just five days before the signing of the so-called Indo-Lanka peace accord, virtually at Indian gun point.

First phase of Eelam war

During the onset of the conflict here, the LTTE routinely carried out raids on predominantly Sinhala villages where civilians were butchered. That had been part of its strategy approved by ‘controllers’ based across the Palk Straits. That had been a volatile period in the run-up to the July 29, 1987, accord. Although India established half a dozen terrorist groups here, the LTTE had been unquestionably the most violent and the dominant group. To New Delhi’s humiliation all such groups supported by it were wiped out by the marauding Tigers.

Those who compared the LTTE with Hamas, or any other group, conveniently forget that the Sri Lankan group caused significant losses to its creator. India lost over 1,300 officers and men, while nearly 3,000 others suffered injuries during the Indian deployment here (July 1987-March 1990).

The world turned a blind eye to what was going on in Sri Lanka in the ’80s. The war launched by India in the early ’80s against Sri Lanka lasted till the signing of the peace accord. That can be broadly identified as phase one of the conflict (1983 July – 1987 July). That first phase can be safely described as an Indian proxy war aimed at creating an environment conducive for the deployment of the Indian Army.

Having compelled President JRJ to accept deployment of the Indian Army in the northern and eastern regions in terms of the “peace accord”, New Delhi sought to consolidate its hold here by disarming all groups, except the one it had handpicked to run the North-East Provincial Council. The Indian Army oversaw the first Provincial Council election held on Nov. 19, 1988, to elect members to the NE council. The whole exercise was meant to ensure the installation of the Varatharaja Perumal led-EPRLF (Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Forint) administration therein.

The second phase (1987 July – 1990 March) saw a war between the Indian Army and the LTTE. During this period, the Indian Army supervised two national elections – presidential on Dec. 19, 1988, and parliamentary on Feb. 15, 1989, that were won by Ranasinghe Premadasa and the UNP.

During that period, the UNP battled the JVP terror campaign and the South bled. The JVP that resorted to unbridled violence against the Indo-Lanka accord, at that time, has ended-up signing several agreements, including one on defence cooperation, recently, and the country is yet to get details of these secret agreements.

Raid on the Maldives

The second phase of the Eelam conflict ended when India pulled out its Army from NE Sri Lanka in March 1990. The sea-borne raid that had been carried out by Indian-trained PLOTE (People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam) targeting Maldivian President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, in Nov. 1988, is perhaps a significant development during the second phase of the conflict, though it was never examined in the right context.

No one – not even the Maldives – found fault with India for exporting terrorism to the island nation. India received accolades for swift air borne intervention to neutralise the PLOTE group. The Indian Navy sank a vessel commandeered by a section of the PLOTE raiders in a bid to escape back to Sri Lanka. The truth is that PLOTE, that had been trained by India to destabilise Sri Lanka, ended-up taking up a lucrative private assignment to overthrow President Gayoom’s administration.

India never regretted the Maldivian incident. It would be pertinent to mention that two boat loads of PLOTE cadres had quietly left Sri Lanka at a time the Indian Navy was responsible for monitoring in and out sea movements.

In the aftermath of the Pahalgam massacre, Pakistan offered to cooperate in what it called a neutral investigation. But India never regretted the catastrophic results of its intervention in Sri Lanka that led to the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi in May 1991, over a year after India pulled out its Army from NE, Sri Lanka.

Resumption of hostilities by the LTTE in June 1990 can be considered as the beginning of the third phase of the conflict. Having battled the Indian Army and gained valuable battle experience, the LTTE, following a 14-month honeymoon with President Ranasinghe Premadasa, resumed hostilities. Within weeks the LTTE gained the upper hand in the northern theatre of operations.

In spite of India banning the LTTE, after the May 1991 assassination of Gandhi, the group continued to grow with the funds pouring in from the West over the years. Regardless of losing Jaffna in 1995, the LTTE consolidated its position, both in the Vanni and the East, to such an extent their victory seemed inevitable.

But resolute political leadership given by Mahinda Rajapaksa ensured that Sri Lanka turned the tables on the LTTE within weeks after the LTTE appeared to be making significant progress at the beginning. Within two years and 10 months (2006 August – 2009 May) the armed forces brought the LTTE to its knees, and the rest is history. As we have said in our earlier columns that victory was soon soured. Spearheaded by Sarath Fonseka, the type of General that a country gets in about once in a thousand years, ended in enmity within, for the simple reason this super hero wanted to collect all the trophies won by many braves.

Post-war developments

Sri Lanka’s war has been mentioned on many occasions in relation to various conflicts/situations. We have observed many distorted/inaccurate attempts to compare Sri Lanka’s war against LTTE with other conflicts/situations.

Unparalleled Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israel, triggered a spate of comments on Sri Lanka’s war against the LTTE. Respected expert on terrorism experienced in Sri Lanka, M.R. Narayan Swamy, discussed the similarities of Sri Lanka’s conflict and the ongoing Israel-Gaza war. New Delhi-based Swamy, who had served UNI and AFP during his decades’ long career, discussed the issues at hand while acknowledging no two situations were absolutely comparable. Swamy currently serves as the Executive Director of IANS (Indo-Asian News Service).

‘How’s Hamas’ attack similar to that of LTTE?’ and ‘Hamas’ offensive on Israel may bring it closer to LTTE’s fate,’ dealt with the issues involved. Let me reproduce Swamy’s comment: “Oct. 7 could be a turning point for Hamas similar to what happened to the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in Sri Lanka in 2006. Let me explain. Similar to Hamas, the LTTE grew significantly over time eventually gaining control of a significant portion of Sri Lanka’s land and coast. The LTTE was even more formidable than Hamas. It had a strong army, growing air force and a deadly naval presence. Unlike Hamas, the LTTE successfully assassinated high ranking political figures in Sri Lanka and India. Notably, the LTTE achieved this without direct support from any country while Hamas received military and financial backing from Iran and some other states. The LTTE became too sure of their victories overtime. They thought they could never be beaten and that starting a war would always make them stronger. But in 2006 when they began Eelam War 1V their leader Velupillai Prabhakaran couldn’t have foreseen that within three years he and his prominent group would be defeated. Prabhakaran believed gathering tens of thousands of Tamils during the last stages of war would protect them and Sri Lanka wouldn’t unleash missiles and rockets. Colombo proved him wrong. They were hit. By asking the people not to flee Gaza, despite Israeli warnings, Hamas is taking a similar line. Punishing all Palestinians for Hamas’ actions is unjust, just like punishing all Tamils for LTTE’s actions was wrong. The LTTE claimed to fight for Tamils without consulting them and Hamas claimed to represent Palestinians without seeking the approval for the Oct.7 strike. Well, two situations are not absolutely comparable. We can be clear that Hamas is facing a situation similar to what the LTTE faced, shortly before its end. Will Hamas meet a similar fate as the LTTE? Only time will answer that question.” The above was said soon after the Oct. 2023 Hamas attack.

Swamy quite conveniently refrained from mentioning India’s direct role in setting up one of the deadliest terror projects in the world here in the ’80s.

Former Editor of The Hindu, Malini Parthasarathy, who also had served as Chairperson of The Hindu Group, released a list of politicians assassinated by the LTTE, as she hit back hard at those who raged against the comparison of the Hamas to the LTTE. The list included two Jaffna District MPs, Arumugam Murugesu Alalasundaram and Visvanathan Dharmalingam, assassinated in early Sept. 1985. Slain Visvanathan Dharmalingam’s son, Dharmalingam Siddharthan, who represents the Vanni electoral district on the Illankai Thamil Arasu Kadchi (ITAK), is on record as having said that the two MPs were abducted and killed by TELO (Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation.) gunmen. The list posted by Parthasarathy included PLOTE leader Uma Maheswaran, assassinated in Colombo in July 1989. The LTTE hadn’t been involved in that killing either. Maheswaran is believed to have been killed by his onetime associates, perhaps over the abortive PLOTE raid on the Maldives in Nov, 1988. India never bothered at least to acknowledge that the Maldives raid was carried out by men trained by India to destabilise Sri Lanka. There is no doubt that Maheswasran’s killers, too, were known to the Indian intelligence at that time.

Before rushing into conclusions regarding Hamas and the LTTE, perhaps a proper examination of the circumstances they emerged is necessary. The two situations – fourth phase of the Eelam conflict and the latest Hamas strike on Israel and the devastating counter attack – cannot be compared under any circumstances. Efforts to compare the two issues is more like comparing apples and oranges, though mutually Tamils and Sinhalese have so many commonalities having intermingled throughout history like the Arabs and Jews.

It is no doubt Jews are a people that suffered persecution throughout known history under Assyrians, Babylonians to Romans and so forth. Such persecution includes expulsion of Jews from England in 1290 and from Spain 1492. So what Hitler and the Germans did was to take the historic process to another extreme.

Yet to blame the Palestinians and treat them like animals and to simply butcher them for the latest uprising by Hamas for all the humiliations and suffering they have been going through non-stop since Naqba in1948, from the time of the creation of Israel is to allow the creators of the problem, including the UK, the USA and United Nations to wash all their sins on the true other victims of this conflict, the Palestinians.

It would be pertinent to mention that Israel, in spite of having one of the world’s best fighting armed forces with 100 percent backing from the West, cannot totally eradicate Hamas the way Sri Lanka dealt with the LTTE. Mind you we did not drop 2000 pound bombs supplied by the US on hapless Tamil civilians to commit genocide as is happening in Palestine in the hands of the Israelis.

The circumstances under which the LTTE launched a large-scale offensive in Aug. 2006 and its objectives had been very much different from that of Hamas. The LTTE really believed that it could have defeated the Sri Lankan military in the North by cutting off the sea supply route from Trincomalee to Kankesanthurai and simultaneously overrunning the Kilali-Muhamalai-Nagarkovil forward defence line (FDL). The total collapse of the FDL could have allowed the LTTE to eradicate isolated fighting formations trapped north of the FDL. But, in the case of the Gaza war, the Hamas strike was meant to provoke Israel to unleash a massive unbridled counter attack that caused maximum losses on the civilians. As Hamas expected the Israeli counter attack has triggered massive protests in the West against their leaders. They have been accused of encouraging violence against Palestine. Saudi Arabia, Jordan and other US allies are under heavy pressure from Muslims and other horrified communities’ world over to take a stand against the US.

But in spite of growing protests, Israel has sustained the offensive action not only against Gaza but Lebanon, Yemen and Iran.

Instead of being grateful to those who risked their lives to bring the LTTE terror to an end, various interested parties are still on an agenda to harm the armed forces reputation.

The treacherous Yahapalana government went to the extent of sponsoring an accountability resolution against its own armed forces at the Geneva-based UNHRC in Oct. 2015. That was the level of their treachery.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Midweek Review

The Broken Promise of the Lankan Cinema:

Asoka & Swarna’s Thrilling-Melodrama – Part III

“‘Dr. Ranee Sridharan,’ you say. ‘Nice to see you again.’

The woman in the white sari places a thumb in her ledger book, adjusts her spectacles and smiles up at you. ‘You may call me Ranee. Helping you is what I am assigned to do,’ she says. ‘You have seven moons. And you have already waisted one.’”

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida

by Shehan Karunatilaka (London: Sort of Books, 2022. p84)

(Continued from yesterday)

Rukmani’s Stardom & Acting Opportunity

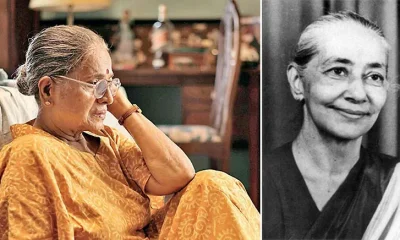

Rukmani Devi is still remembered for her incomparable singing voice and her studio photograph by Ralex Ranasinghe with its hint of Film Noir mystery and seduction, and for the role of Blanch Dubois she played in Dhamma Jagoda’s Vesmuhunu, an adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. This is a role she shared on alternate nights with Irangani Serasinghe in the late 60s or early 70s. (See my Island Essays, 2024, p114) She was immensely happy to be able to act in a modern western classic directed by a visionary theatre director like Dhamma Jagoda and it was to his credit that he chose to give her that role when all acting roles had dried up for her. I observed those rehearsals held at Harrold Peiris’ open garage.

I, too, am happy that Swarna has had a chance to perform again in her 70s. The question is, how exactly has she used that very rare opportunity to act in a film that has doubled its production cost within two months, and now showing in private screenings in multiplexes in Australia with English subtitles, with ambitions to be shown on Netflix and Amazon Prime. These outlets also now fund films and make challenging mini-series. Rani has clearly been produced and marketed with this global distribution in mind. How does this important fact affect Swarna’s style of acting and the aesthetics of Asoka’s script, are the questions I wish to explore in the final section of this piece.

A Sensational-Thrilling Political & Family Melodrama

‘Melodrama’ is a popular genre with a history that goes back to 19th century theatre in the west and with the advent of film, Hollywood took it up as it offered a key set of thrilling devices known as ‘Attractions’, for structuring and developing a popular genre cinema. The word ‘Melodrama’ is a compound of the Greek word for music ‘melos’ and drama as an action, with the connotation of a highly orchestrated set of actions. The orchestration (not only with sound but also the speed and rhythm of editing, dramatic expressive lighting, ‘histrionic’ acting, etc.,) always reaches toward thrilling climaxes and at times exaggerated display of emotions. The plots are sensational, propelled by coincidences and written to reach climaxes and dramatic reversals of fortune, and sudden revelations. Hollywood was famous for its happy endings with resolution of the dramatised conflicts, while Hindi melodramas and Lankan copies often ended sadly.

In the history of cinema there are highly sophisticated melodramas within Hollywood, classical Hindi cinema and also in European art cinema. Rainer Werner Fassbinder was one of the German directors who developed a modern ‘Brechtian-Melodrama’ of extraordinary political and aesthetic power in the 70s. And of course, there are very poorly conceived melodramas too like many of the Sinhala films which were copies of Indian prototypes. Melodramatic devices inflect the different genres of Hollywood, for example the Gangster Film, the Western and created durable genre types in character, e.g. the Gangster, the Lonesome Cowboy and Indians; all national stereotypes, one embodying the underbelly of American capitalism, an anti-hero and the other the American hero actualising The American Dream. ‘The Indian,’ merely the collateral damage of this phantasy!

When the stories were centred on women the genre classification was ‘Women’s Melodrama’ as it dealt with interpersonal relations, conflicts, and sadness centred on the home primarily. Feminist film theory has developed a vast archive of scholarship on the melodramatic genre, cross-culturally, with a special focus on Hollywood and Hindi cinema decades prior to the formation we now call Bollywood, made with transnational capital and global reach. It was assumed that the audience for the family melodramas was female and that as women, we enjoy crying at the cinema, hence the condescending name ‘The Weepies’. I cut my scholarly/critical teeth studying these much-maligned melodramatic films for my doctorate, which I had enjoyed while growing up in a long-ago Ceylon.

Asoka’s Melodramatic Turn

Asoka in Alborada, but more so in Rani has made melodramatic films with his own ‘self-expressive’ variations on the structure, with an ‘Art Cinema’ gloss. He has said that Rani is more like Alborada and unlike his previous films made during the civil war. This is quite obvious. Though the advertising tag line for Alborada claimed it as a ‘Poetic film that Neruda never made’ it was a straightforward narrative film. I have argued in a long essay (‘Psycho-Sexual Violence in the Sinhala Cinema: Parasathumal & Alborada’, in Lamentation of the Dawn, ed. S. Chandrajeewa, 2022, also tr. into Sinhala, 2023), that the staging of the rape of the nameless, silent, Dalit woman is conceived in a melodramatic manner playing it for both critique and exciting thrills. This is a case of both having his cake and eating it.

Swarna’s Melodramatic Turn

The film appears to be constructed, plotted melodramatically, to demonstrate Swarna’s ability to perform dramatic scenes of high excitement in areas of taboo, the opportunity for which is unavailable to a Sinhala actress, in a Sinhala film, playing the role of a Sinhala Buddhist mother, who has lost her son to an act of terror unleashed by the Sinhala-Buddhist State terror and Sinhala-Buddhist JVP.

In short, Swarna has been given the opportunity to demonstrate how well she can perform a range of Melodramatic emotions that go from say A to, say D. She has been given the chance to move smoothly from English to Sinhala as the middle classes do; use the two most common American expletives which are part of the American vernacular; drink for pleasure but also to the point of getting drunk; offer alcohol to her baffled domestic worker; coax her son and friends to drink; dance with them in an inebriated state; pour alcohol, whisky, not arrack, like one would pour water from a bottle; chain smoke furiously; dash a full mug of tea on the floor in a rage; crumple on the floor sobbing uncontrollably; shout at her loyal aid Karu; speak with sarcasm to a police officer insisting that she is ‘Dr Manorani …’ not ‘Miss or Mrs’, like feminists did back in the day; chat intimately with a minister of the government; look angrily and scowl at President Premadasa when he comes to the funeral house to condole with her; stage Richard’s funeral in a Catholic church with a stain glass window of the Pieta; to quote a well-known Psalm of David from the Bible, ‘Oh Absalom my son, Oh my son!’; etc.

Rani is Swarna’s chance to show that she can perform in ways that no Sinhala script has allowed a Sinhala actor to do up to now, that is, behave like the Sinhala cinema’s fantasy of how the upper-class Anglophone Lankan women behave. In short not unlike, but much worse, than the ‘bad girls’ in the Sinhala melodramatic genre cinema who always ended up in a Night Club, the locus of licentiousness that tempt them. I am thinking of Pitisara Kella from the 50s and a host of other films. Sinhala cinema simply cannot convincingly present the upper-class English-speaking milieu, with any nuance and conviction, it just feels very stilted, poorly acted therefore. Saying this is not class snobbery on my part. Even Lester James Peries from this very upper class and a Roman Catholic, in Delowak Atara couldn’t do it with Irangani Serasinghe and others. The dialogue meant to be serious or just plain normal sounded stilted and even funny. But when Lester did the Walauwa as in Nidhahanaya, it was brilliant, one of our classics. Brecht it was who said (on the eve of WW2, creating a Modern Epic mode of theatre in exile, that it’s not easy to make drama about current events. It’s much easier to look back with nostalgia at a genteel aristocratic Sinhala past for sure.

In taking the opportunity to explore kinetic and emotional behaviour considered to be taboo for a Sinhala woman, a fantasy Tamil woman has been fabricated. The plot of Rani is constructed by Asoka to provide Swarna the opportunity to indulge in these very taboos. In short, the fictional Tamil Rani offers Swarna an acting opportunity to improve her career prospects in the future. In so doing she has weakened her ability, I fear, to evolve as an actress.

A Domestic Melodrama: The House Suspended in a Void

If Swarna so desired, if the script ‘allowed her’ to, she could have tried to develop a quieter, more restrained and therefore a more powerful Rani. A friend of the family, when asked, said that, “The most striking feature of Manorani was her quiet, confident dignity, before and after Richard.” To testify to such a person, Asoka and Swarna could have asked the obvious question, did she have any close friendships formed as undergraduates, who supported her during this tragedy, as there certainly were cherished friends who shared her grief. After all, she was among the elite first generations of Ceylonese women to enter University in the 1940, to medical school at that!

Asoka and Swarna have entrapped their Rani in a vacuum of a house, friendless, with a little cross on Richard’s wall to signify religion. A lot of effort has gone into the set decoration and art direction of the house, as in Alborada, to stage a fantasy/phantasy melodramatic scenario. There is no real sensory, empathetic feel and understanding of the ethos (character), of this urbane Anglophone Ceylonese-Lankan mother and son, hence the fictionalised scenarios feel synthetic, cosmetic in the best traditions of the Sinhala genre cinema’s representation of the ‘excessive and even grotesque upper-class’. Except, here the Realism of the mise-en-scene (the old-world airy house and furniture and composition of the visual components) makes claims to a realist authenticity. A little modest research would have shown that Manorani and Richard moved from one rented apartment to another in the last few years of his life and when he was abducted, lived on the upper-floor of a house, in a housing estate in Rajagiriya. Asoka said in an interview that it wasn’t possible to find in Colombo the kind of old house they required for Rani. So, they went out of town to find the ideal house suited to stage their phantasy.

I suspect that it was Swarna who called shots this time, not Asoka who was recovering from a serious illness. He said that she brought the project to him and the producer and that he had no idea of making a film on Manorani, but added that he wrote the script within 3 months. I suspect that this Rani, (this out of control, angry, scowling, bad tempered, lamenting, hysterical Rani, reaching for the alcohol and cigarettes to assuage her grief, performing one sensational, thrilling melodramatic turn after another), was Swarna’s conception, her version of Manorani that she has nursed for 28 long years. Had she resisted this temptation to display her high-intensity acting-out skills yet again, she might just have been able to tap unsuspected resources within herself which she may still have as a serious actress. Its these latent affective depths that Rukmani Devi undoubtedly tapped when she was invited to play the drunken and lost Blanche Dubois, in A Streetcar Named Desire in Sinhala, as a desperate, drunken, aristocratic lady, in Dhamma Jagoda’s Vesmuhunu (1971?).

Jagoda / Irangani

It is reported that before going on stage, Rukmani Devi went on her hands and knees to pay her respects to Dhamma, not as feudal act of deference but to acknowledge his Shilpiya Nuwana, craft knowledge/intelligence’, as one very perceptive Sinhala critic put it. That gesture of Vandeema was foreign to the Tamil Christian Rukmani Devi, but nevertheless it shows her sense of immense gratitude to Dhamma for having taken her into a zone of expression (a dangerous territory emotionally for dedicated vulnerable actors), that she had never experienced before, so late in her life. But ‘late’ is relative to gender, then she was only in her 50s!

Challenge is what serious actors yearn for, strange beings who may suggest to us intensities that sustain and amplify life, all life. Swarna might usefully think about Rukmani Devi, her life and her star persona as a Tamil star in countless sarala Sinhala films, in whose shadow and echo every single Sinhala actress has entered the limelight, Swarna more so now than any other!

As for Asoka, he needs to rest and take care of himself before he commits himself to this recent track of films which are yielding less and less with each of the two films done back to back. His body of work is too important to trash it with this kind of half thought out ‘Tales of Sound and Fury’, which is a precise definition of Melodrama at its best. This film, alas, is not one of those.

That young Tamil women, often silent and traumatised, appeared following Sinhala soldiers in Lankan ‘civil-war cinema’ of the modernists, all male, is a troubling phenomenon. A ‘Sinhala Orientalism’, an exoticising of Tamil and Dalith young women as Other, is at work in some of the civil war films, as in Alborada and Rani. And then this very elevation always leads to unleashing psycho/sexual and/or other forms of violence, because the elevation (Mother Goddess in Alborada) only feeds violent male psychosexual phantasies, which in the Sinhala cinema often leads to the violence of rape and other forms of violence towards women, both Tamil and Sinhala. (To be continued)

by Laleen Jayamanne

Midweek Review

Thirty Thousand and Counting….

Many thousands in the annual grades race,

Are brimming with the magical feel of success,

And they very rightly earn warm congrats,

But note, you who are on the pedestals of power,

That 30,000 or more are being left far behind,

In these no-holds-barred contests to be first,

Since they have earned the label ‘All Fs’,

And could fall for the drug-pusher’s lure,

Since they may be on the threshold of despair…

Take note, and fill their lives with meaning,

Since they suffer for no fault of theirs.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoOTRFU Beach Tag Rugby Carnival on 24th May at Port City Colombo

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRanil’s Chief Security Officer transferred to KKS

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoRemembering Dr. Samuel Mathew: A Heart that Healed Countless Lives

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe Broken Promise of the Lankan Cinema: Asoka & Swarna’s Thrilling-Melodrama – Part IV

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoTrump tariffs and their effect on world trade and economy with particular

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoRadisson Blu Hotel, Galadari Colombo appoints Marko Janssen as General Manager

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCCPI in April 2025 signals a further easing of deflationary conditions

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoA piece of home at Sri Lankan Musical Night in Dubai