Features

Unusual Challenges in Iraq

Part Five

PASSIONS OF A GLOBAL HOTELIER

Dr. Chandana (Chandi) Jayawardena DPhil

President – Chandi J. Associates Inc. Consulting, Canada

Founder & Administrator – Global Hospitality Forum

chandij@sympatico.ca

Planning for Two Hotel Operations

I was thrilled when the General Manager of Hotel Babylon Oberoi confidentially informed me to be ready to take over the management of a competitor five-star hotel in Baghdad. That same day, I began my strategic planning, assuming the takeover would occur within two weeks. Discreetly, I identified chefs, restaurant managers, and bar supervisors who could be transferred on short notice.

My initial reaction was a shock. The Iraqi government had abruptly decided to terminate the management contract of another hotel, which was run by a professional team employed by a well-known international hotel corporation. I felt saddened for the expatriate managers who would be forced to leave Iraq once Oberoi took over the management. However, in the business world, one organization’s misfortune often translates to another’s opportunity. I was eager to oversee two large operations with 18 food and beverage outlets and around 400 employees. I always loved the challenge of running multiple operations concurrently.

Radeef – The Second Fiddle

In 1989, Iraq’s five-star hotels managed by international corporations were generally allowed to operate with some degree of autonomy. However, the Iraqi government frequently interfered indirectly with spies and occasionally interfered directly with the style of management. These hotels were primarily managed by expatriates, with a few key positions, such as Human Resources Manager, Chief Engineer, and Security Manager, held by qualified and experienced locals. All other management positions at hotels were held by foreigners, with one exception.

Each hotel also had an Iraqi Deputy General Manager, known as the Radeef, meaning “second fiddle.” Most Radeefs had no qualifications or experience in hotel management; their main requirement was loyalty to Saddam Hussein’s Baath Party. They reported directly to the State Organization of Tourism in Iraq (Tourism) and were tasked with monitoring the actions of expatriate managers, reporting any unusual or suspicious activities. In 1989 no one was trusted in Iraq.

Our hotel’s Radeef was a former school teacher before being assigned to Hotel Babylon Oberoi and he was clueless about hotel operations and administration. He never attended our management team meetings and only left his office to dine in the hotel restaurants with Iraqi VIPs and attend confidential meetings outside the hotel.

Recognizing Radeefs’ importance to the owners, I tried to maintain a cordial relationship with him, but he rarely communicated with us. After an incident where the American General Manager at the other hotel showed disrespect to the head of Tourism, leading to their expected loss of the management contract, our Radeefs’ behaviour changed dramatically. He became more active and interfering, likely following direct orders from his superiors at the Baath Party.

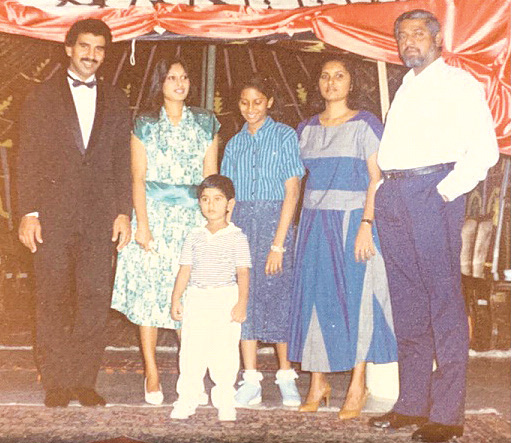

- With our friends the Hapuwatte family

- Marlon and me with our Kurdish friends Azad and his daughter Jiyan

The Radeef began walking around the hotel, interfering in departments, giving instructions to junior staff, and micromanaging. At a morning briefing, I informed the General Manager, “Mr. Misra, I have a new problem in my division. Radeef has started giving direct orders to the restaurant managers and head waiters. Can you kindly inform him to go through me for any changes in the food and beverage division, and I will respectfully comply with any reasonable request. He should follow the chain of command.”

At that point Misra gestured for me to stop talking. When I continued to complain, saying, “Radeef must not undermine the authority of divisional heads and departmental managers,” Misra became annoyed. He stood up and gestured with his index finger for me to follow him, leaving the rest of our management team baffled.

I followed Misra to the middle of the front garden of the hotel. “Mr. Jayawardena, please don’t complain about Radeef in my office, which is wiretapped! Everything we discuss there can be heard at the Baath Party head office.” I was sceptical but decided to keep quiet.

Misra continued, “Look, I fully understand your frustration. I will deal with it. With the forthcoming favour Oberoi will do for Tourism by taking over the other hotel, I can negotiate to replace the Radeef with a properly qualified and experienced hotelier as the new Deputy General Manager. No five-star hotel in Iraq has been allowed to do this before. In fact, the Radeef will be replaced next week by Mr. P. G. Mathews, a well-known hotelier from India and a graduate of the Oberoi Hotel School.”

Wiretapping as a Welcome Gesture

Within a week, the Radeef left and vacated his office at the hotel. While the maintenance and housekeeping staff prepared the office for the arrival of our new Deputy General Manager, two outsiders with rolls of wire approached me and asked, “Which office will be occupied by Mr. P. G. Mathews?” When I inquired about their role, they responded without hesitation, “We are electricians from the Baath Party head office. We must do an urgent wiring job.” They openly wiretapped the office and left.

When P. G. Mathews (PG) arrived with his wife Roshni and their four-year-old daughter Mihika, my family immediately became good friends with them. Even after 35 years, we keep in touch with them. When I warned PG about his wiretapped office, he was surprised. Following my deputy, T. P. Singh’s funny example, I told PG, “Welcome to Iraq!” PG did not find it amusing.

Our Social Life in Baghdad

Despite the unusual challenges we faced in Baghdad, we enjoyed the friendliness of the Iraqi people and the camaraderie among our expatriate colleagues and friends. The expatriate community was like a close-knit group of career diplomats, always sticking together and watching each other’s backs. We celebrated every occasion, such as birthdays of expatriate managers at the hotel or their kids, with parties.

Our Sri Lankan friends from other hotels, especially the Happuwatte family (Kamal, Preethi, and their daughter Varunika) from Al Rasheed Hotel, visited us frequently, and we visited them at their staff quarters. We also learned from each other’s experiences living in Iraq during these peaceful yet uncertain times.

The Plight of the Kurds

Coming from Sri Lanka, which was in 1989 embroiled in an ethnic separatist war, I was naturally interested in the minority Kurds in Iraq and some neighbouring countries. During my visits to the northern parts of Iraq, I had the opportunity to associate with Kurdish communities.

Some of our new Kurdish friends visited us at our suite at Hotel Babylon Oberoi, though they feared to speak openly about their plight. A regular Kurdish visitor to our suite was a single father named Azad and his three-year-old beautiful daughter, Jiyan. My son Marlon was intrigued by Jiyan’s blond hair and blue eyes, features that are not uncommon among certain Kurdish tribes.

Kurdish people, or Kurds, are an Iranic ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northern Syria. Kurds speak the Kurdish languages and the Zaza–Gorani languages. The Kurdish population worldwide is estimated to be over 30 million. Despite their significant population, Kurds do not comprise a majority in any country, making them a stateless people.

Much of the geographical and cultural region of Iraqi Kurdistan is part of the Kurdistan Region, an autonomous area recognized by the Constitution of Iraq. During World War I, the British and French divided West Asia arbitrarily, creating waves of social, political, religious, and economic conflicts over the next century. Defiant to the British, in 1922, Shaikh Mahmud declared a Kurdish Kingdom with himself as king. It took two years for the British to bring Kurdish areas into submission. During World War II, the power vacuum in Iraq was exploited by the Kurdish tribes, leading to a rebellion in the north that effectively gained control of Kurdish areas until 1945, when the Iraqi government, with British support, could once again subdue the Kurds.

During the Iran–Iraq War, the Iraqi government implemented harsh anti-Kurdish policies, resulting in a de facto civil war. Iraq was widely condemned by the international community but was never seriously punished for its oppressive measures. These included the use of chemical weapons against the Kurds, resulting in thousands of deaths just before I arrived in Iraq in 1989. Some accused Saddam Hussein’s government of committing systematic genocide against the Kurdish people, including the wholesale destruction of some 2,000 villages and the slaughter of around 50,000 rural Kurds, by the most conservative estimates.

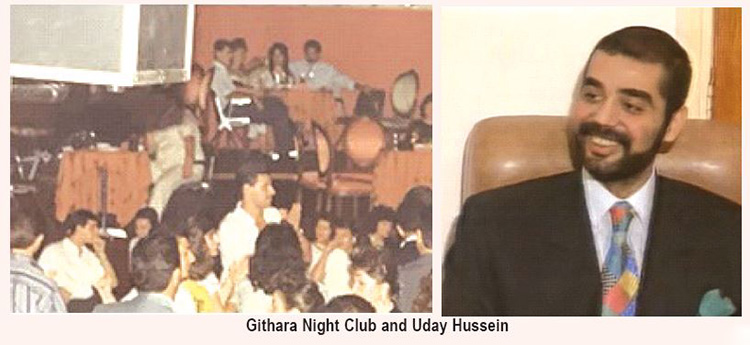

Hosting Uday Hussein

While awaiting the decision from the Oberoi Hotel corporate office about taking over the management of a competitor hotel in Baghdad, I was compelled to regularly provide hospitality to the notorious Uday Hussein.

Uday, the elder son of President Saddam Hussein, was an influential and feared figure in Iraq. He held numerous positions, including sports chairman, military officer, and businessman, and was the head of the Iraqi Olympic Committee and Iraq Football Association. He also commanded the Fedayeen Saddam, a loyalist paramilitary organization that served as his father’s personal guard. Although dynastic succession is rare in a federal parliamentary republic, Uday was widely considered Saddam Hussein’s heir apparent.

Before my first meeting with Uday, I had heard many horror stories about his behaviour. He was reportedly erratically ruthless and intimidating to both perceived adversaries and close friends. Relatives and personal acquaintances were often victims of his violence and rage. Witnesses alleged that he was guilty of rape, murder, and various forms of torture, including the arrest and torture of Iraqi Olympic athletes and national football team members whenever they lost a match.

Uday was reputed as a flamboyant womanizer who financed his lavish lifestyle largely through smuggling and racketeering. He was feared in many circles in Iraq, and people generally avoided making direct eye contact with him. It was my misfortune that Uday’s favourite hangout night club happened to be Githara at Hotel Babylon Oberoi.

One Thursday around 10:00 pm, while I was working as the hotel’s duty manager, I was abruptly approached at the hotel lobby by a tough-looking man in uniform. “I am Ali, the head bodyguard for His Excellency, Uday Hussein. Clear our favourite corner at Githara Night Club for six VVIPs,” he commanded. His words were not a request but an order. “Sure, will do that immediately”, I said and reached to shake his hand, a gesture he rudely ignored.

Working with staff accustomed to these visits, especially on Thursday nights, I quickly made the arrangements. When the group arrived, they were all armed with guns, which they did not surrender at the entrance to the night club, unlike all other patrons who obeyed this house rule. None in my team had the courage to request Uday’s group to respect the house rules.

I clearly remember all details of my first encounter with Uday Hussein, although he avoided speaking with me directly. In his eyes hoteliers were simply servants who must cater to whims and fancies of VVIPs. He was imposing, nearly six and a half feet tall, and looked much older than his official age of 25 in 1989. There was always uncertainty about his exact birthday or whether the person in front of me was Uday himself or his body double, who was reputedly forced to undergo many plastic surgeries. Like his bodyguards, Uday was already under the influence of alcohol. When he spoke with his five bodyguards, I noticed that he had difficulty speaking clearly due to an abnormality in his mouth.

As soon as the group settled in their favourite corner, they scanned the night club for attractive single women. The atmosphere changed immediately; most of the other customers and all our night club staff looked uncomfortable and worried.

Ali then gave his second order to the Night Club Manager, “Twelve portions of the usual! Now!” The bar staff knew the drill and promptly prepared a strong cocktail with whiskey, brandy, vodka, cognac, and champagne. “That’s his favourite to get the girls drunk,” my deputy, T. P. Singh, whispered in my ear. “Boss, I am off now. As per your new instructions, I must return to work before breakfast service. Enjoy your duty manager shift till 4:00 am,” TP left, looking relieved.

I observed as the cocktail was served in a large ‘cup of friendship’, and Uday’s new female friends had to drink it all. Uday was known for forcing guests to consume large quantities of alcohol at his parties. According to some rumours, whoever earned Uday’s friendship had to drink that cocktail, also named the ‘Uday Saddam Hussein’. They were preparing for a night of ‘fun, outrageous adventures, and horror’.

To be continued next week, including a section: ‘My Final Encounter with Uday Hussein’…

Features

Sustaining good governance requires good systems

A prominent feature of the first year of the NPP government is that it has not engaged in the institutional reforms which was expected of it. This observation comes in the context of the extraordinary mandate with which the government was elected and the high expectations that accompanied its rise to power. When in opposition and in its election manifesto, the JVP and NPP took a prominent role in advocating good governance systems for the country. They insisted on constitutional reform that included the abolition of the executive presidency and the concentration of power it epitomises, the strengthening of independent institutions that overlook key state institutions such as the judiciary, public service and police, and the reform or repeal of repressive laws such as the PTA and the Online Safety Act.

The transformation of a political party that averaged between three to five percent of the popular vote into one that currently forms the government with a two thirds majority in parliament is a testament to the faith that the general population placed in the JVP/ NPP combine. This faith was the outcome of more than three decades of disciplined conduct in the aftermath of the bitter experience of the 1988 to 1990 period of JVP insurrection. The manner in which the handful of JVP parliamentarians engaged in debate with well researched critiques of government policy and actions, and their service in times of disaster such as the tsunami of 2004 won them the trust of the people. This faith was bolstered by the Aragalaya movement which galvanized the citizens against the ruling elites of the past.

In this context, the long delay to repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act which has earned notoriety for its abuse especially against ethnic and religious minorities, has been a disappointment to those who value human rights. So has been the delay in appointing an Auditor General, so important in ensuring accountability for the money expended by the state. The PTA has a long history of being used without restraint against those deemed to be anti-state which, ironically enough, included the JVP in the period 1988 to 1990. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), published in December 2025, is the latest attempt to repeal and replace the PTA. Unfortunately, the PSTA largely replicates the structure, logic and dangers of previous failed counter terrorism bills, including the Counter Terrorism Act of 2018 and the Anti Terrorism Act proposed in 2023.

Misguided Assumption

Despite its stated commitment to rule of law and fundamental rights, the draft PTSA reproduces many of the core defects of the PTA. In a preliminary statement, the Centre for Policy Alternatives has observed among other things that “if there is a Detention Order made against the person, then in combination, the period of remand and detention can extend up to two years. This means that a person can languish in detention for up to two years without being charged with a crime. Such a long period again raises questions of the power of the State to target individuals, exacerbated by Sri Lanka’s history of long periods of remand and detention, which has contributed to abuse and violence.” Human Rights lawyer Ermiza Tegal has warned against the broad definition of terrorism under the proposed law: “The definition empowers state officials to term acts of dissent and civil disobedience as ‘terrorism’ and will lawfully permit disproportionate and excessive responses.” The legitimate and peaceful protests against abuse of power by the authorities cannot be classified as acts of terror.

The willingness to retain such powers reflects the surmise that the government feels that keeping in place the structures that come from the past is to their benefit, as they can utilise those powers in a crisis. Due to the strict discipline that exists within the JVP/NPP at this time there may be an assumption that those the party appoints will not abuse their trust. However, the country’s experience with draconian laws designed for exceptional circumstances demonstrates that they tend to become tools of routine governance. On the plus side, the government has given two months for public comment which will become meaningful if the inputs from civil society actors are taken into consideration.

Worldwide experience has repeatedly demonstrated that integrity at the level of individual leaders, while necessary, is not sufficient to guarantee good governance over time. This is where the absence of institutional reform becomes significant. The aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah in particular has necessitated massive procurements of emergency relief which have to be disbursed at maximum speed. There are also significant amounts of foreign aid flowing into the country to help it deal with the relief and recovery phase. There are protocols in place that need to be followed and monitored so that a fiasco like the disappearance of tsunami aid in 2004 does not recur. To the government’s credit there are no such allegations at the present time. But precautions need to be in place, and those precautions depend less on trust in individuals than on the strength and independence of oversight institutions.

Inappropriate Appointments

It is in this context that the government’s efforts to appoint its own preferred nominees to the Auditor General’s Department has also come as a disappointment to civil society groups. The unsuitability of the latest presidential nominee has given rise to the surmise that this nomination was a time buying exercise to make an acting appointment. For the fourth time, the Constitutional Council refused to accept the president’s nominee. The term of the three independent civil society members of the Constitutional Council ends in January which would give the government the opportunity to appoint three new members of its choice and get its way in the future.

The failure to appoint a permanent Auditor General has created an institutional vacuum at a critical moment. The Auditor General acts as a watchdog, ensuring effective service delivery promoting integrity in public administration and providing an independent review of the performance and accountability. Transparency International has observed “The sequence of events following the retirement of the previous Auditor General points to a broader political inertia and a governance failure. Despite the clear constitutional importance of the role, the appointment process has remained protracted and opaque, raising serious questions about political will and commitment to accountability.”

It would appear that the government leadership takes the position they have been given the mandate to govern the country which requires implementation by those they have confidence in. This may explain their approach to the appointment (or non-appointment) at this time of the Auditor General. Yet this approach carries risks. Institutions are designed to function beyond the lifespan of any one government and to protect the public interest even when those in power are tempted to act otherwise. The challenge and opportunity for the NPP government is to safeguard independent institutions and enact just laws, so that the promise of system change endures beyond personalities and political cycles.

by Jehan Perera

Features

General education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

General education reform presents an opportunity to explore ways to promote social and ethnic cohesion. A school curriculum could foster shared values, empathy, and critical thinking, through social studies and civics education, implement inclusive language policies, and raise critical awareness about our collective histories. Yet, the government’s new policy document, Transforming General Education in Sri Lanka 2025, leaves us little to look forward to in this regard.

The policy document points to several “salient” features within it, including: 1) a school credit system to quantify learning; 2) module-based formative and summative assessments to replace end-of-term tests; 3) skills assessment in Grade 9 consisting of a ‘literacy and numeracy test’ and a ‘career interest test’; 4) a comprehensive GPA-based reporting system spanning the various phases of education; 5) blended learning that combines online with classroom teaching; 6) learning units to guide students to select their preferred career pathways; 7) technology modules; 8) innovation labs; and 9) Early Childhood Education (ECE). Notably, social and ethnic cohesion does not appear in this list. Here, I explore how the proposed curriculum reforms align (or do not align) with the NPP’s pledge to inculcate “[s]afety, mutual understanding, trust and rights of all ethnicities and religious groups” (p.127), in their 2024 Election Manifesto.

Language/ethnicity in the present curriculum

The civil war ended over 15 years ago, but our general education system has done little to bring ethnic communities together. In fact, most students still cannot speak in the “second national language” (SNL) and textbooks continue to reinforce negative stereotyping of ethnic minorities, while leaving out crucial elements of our post-independence history.

Although SNL has been a compulsory subject since the 1990s, the hours dedicated to SNL are few, curricula poorly developed, and trained teachers few (Perera, 2025). Perhaps due to unconscious bias and for ideological reasons, SNL is not valued by parents and school communities more broadly. Most students, who enter our Faculty, only have basic reading/writing skills in SNL, apart from the few Muslim and Tamil students who schooled outside the North and the East; they pick up SNL by virtue of their environment, not the school curriculum.

Regardless of ethnic background, most undergraduates seem to be ignorant about crucial aspects of our country’s history of ethnic conflict. The Grade 11 history textbook, which contains the only chapter on the post-independence period, does not mention the civil war or the events that led up to it. While the textbook valourises ‘Sinhala Only’ as an anti-colonial policy (p.11), the material covering the period thereafter fails to mention the anti-Tamil riots, rise of rebel groups, escalation of civil war, and JVP insurrections. The words “Tamil” and “Muslim” appear most frequently in the chapter, ‘National Renaissance,’ which cursorily mentions “Sinhalese-Muslim riots” vis-à-vis the Temperance Movement (p.57). The disenfranchisement of the Malaiyaha Tamils and their history are completely left out.

Given the horrifying experiences of war and exclusion experienced by many of our peoples since independence, and because most students still learn in mono-ethnic schools having little interaction with the ‘Other’, it is not surprising that our undergraduates find it difficult to mix across language and ethnic communities. This environment also creates fertile ground for polarizing discourses that further divide and segregate students once they enter university.

More of the same?

How does Transforming General Education seek to address these problems? The introduction begins on a positive note: “The proposed reforms will create citizens with a critical consciousness who will respect and appreciate the diversity they see around them, along the lines of ethnicity, religion, gender, disability, and other areas of difference” (p.1). Although National Education Goal no. 8 somewhat problematically aims to “Develop a patriotic Sri Lankan citizen fostering national cohesion, national integrity, and national unity while respecting cultural diversity (p. 2), the curriculum reforms aim to embed values of “equity, inclusivity, and social justice” (p. 9) through education. Such buzzwords appear through the introduction, but are not reflected in the reforms.

Learning SNL is promoted under Language and Literacy (Learning Area no. 1) as “a critical means of reconciliation and co-existence”, but the number of hours assigned to SNL are minimal. For instance, at primary level (Grades 1 to 5), only 0.3 to 1 hour is allocated to SNL per week. Meanwhile, at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), out of 35 credits (30 credits across 15 essential subjects that include SNL, history and civics; 3 credits of further learning modules; and 2 credits of transversal skills modules (p. 13, pp.18-19), SNL receives 1 credit (10 hours) per term. Like other essential subjects, SNL is to be assessed through formative and summative assessments within modules. As details of the Grade 9 skills assessment are not provided in the document, it is unclear whether SNL assessments will be included in the ‘Literacy and numeracy test’. At senior secondary level – phase 1 (Grades 10-11 – O/L equivalent), SNL is listed as an elective.

Refreshingly, the policy document does acknowledge the detrimental effects of funding cuts in the humanities and social sciences, and highlights their importance for creating knowledge that could help to “eradicate socioeconomic divisions and inequalities” (p.5-6). It goes on to point to the salience of the Humanities and Social Sciences Education under Learning Area no. 6 (p.12):

“Humanities and Social Sciences education is vital for students to develop as well as critique various forms of identities so that they have an awareness of their role in their immediate communities and nation. Such awareness will allow them to contribute towards the strengthening of democracy and intercommunal dialogue, which is necessary for peace and reconciliation. Furthermore, a strong grounding in the Humanities and Social Sciences will lead to equity and social justice concerning caste, disability, gender, and other features of social stratification.”

Sadly, the seemingly progressive philosophy guiding has not moulded the new curriculum. Subjects that could potentially address social/ethnic cohesion, such as environmental studies, history and civics, are not listed as learning areas at the primary level. History is allocated 20 hours (2 credits) across four years at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), while only 10 hours (1 credit) are allocated to civics. Meanwhile, at the O/L, students will learn 5 compulsory subjects (Mother Tongue, English, Mathematics, Science, and Religion and Value Education), and 2 electives—SNL, history and civics are bunched together with the likes of entrepreneurship here. Unlike the compulsory subjects, which are allocated 140 hours (14 credits or 70 hours each) across two years, those who opt for history or civics as electives would only have 20 hours (2 credits) of learning in each. A further 14 credits per term are for further learning modules, which will allow students to explore their interests before committing to a A/L stream or career path.

With the distribution of credits across a large number of subjects, and the few credits available for SNL, history and civics, social/ethnic cohesion will likely remain on the back burner. It appears to be neglected at primary level, is dealt sparingly at junior secondary level, and relegated to electives in senior years. This means that students will be able to progress through their entire school years, like we did, with very basic competencies in SNL and little understanding of history.

Going forward

Whether the students who experience this curriculum will be able to “resist and respond to hegemonic, divisive forces that pose a threat to social harmony and multicultural coexistence” (p.9) as anticipated in the policy, is questionable. Education policymakers and others must call for more attention to social and ethnic cohesion in the curriculum. However, changes to the curriculum would only be meaningful if accompanied by constitutional reform, abolition of policies, such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act (and its proxies), and other political changes.

For now, our school system remains divided by ethnicity and religion. Research from conflict-ridden societies suggests that lack of intercultural exposure in mono-ethnic schools leads to ignorance, prejudice, and polarized positions on politics and national identity. While such problems must be addressed in broader education reform efforts that also safeguard minority identities, the new curriculum revision presents an opportune moment to move this agenda forward.

(Ramya Kumar is attached to the Department of Community and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

by Ramya Kumar

Features

Top 10 Most Popular Festive Songs

Certain songs become ever-present every December, and with Christmas just two days away, I thought of highlighting the Top 10 Most Popular Festive Songs.

The famous festive songs usually feature timeless classics like ‘White Christmas,’ ‘Silent Night,’ and ‘Jingle Bells,’ alongside modern staples like Mariah Carey’s ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You,’ Wham’s ‘Last Christmas,’ and Brenda Lee’s ‘Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree.’

The following renowned Christmas songs are celebrated for their lasting impact and festive spirit:

* ‘White Christmas’ — Bing Crosby

The most famous holiday song ever recorded, with estimated worldwide sales exceeding 50 million copies. It remains the best-selling single of all time.

* ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You’ — Mariah Carey

A modern anthem that dominates global charts every December. As of late 2025, it holds an 18x Platinum certification in the US and is often ranked as the No. 1 popular holiday track.

Mariah Carey: ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You’

* ‘Silent Night’ — Traditional

Widely considered the quintessential Christmas carol, it is valued for its peaceful melody and has been recorded by hundreds of artistes, most famously by Bing Crosby.

* ‘Jingle Bells’ — Traditional

One of the most universally recognised and widely sung songs globally, making it a staple for children and festive gatherings.

* ‘Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree’ — Brenda Lee

Recorded when Lee was just 13, this rock ‘n’ roll favourite has seen a massive resurgence in the 2020s, often rivaling Mariah Carey for the top spot on the Billboard Hot 100.

* ‘Last Christmas’ — Wham!

A bittersweet ’80s pop classic that has spent decades in the top 10 during the holiday season. It recently achieved 7x Platinum status in the UK.

* ‘Jingle Bell Rock’ — Bobby Helms

A festive rockabilly standard released in 1957 that remains a staple of holiday radio and playlists.

* ‘The Christmas Song (Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire)’— Nat King Cole

Known for its smooth, warm vocals, this track is frequently cited as the ultimate Christmas jazz standard.

Wham! ‘Last Christmas’

* ‘It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year’ — Andy Williams

Released in 1963, this high-energy big band track is famous for capturing the “hectic merriment” of the season.

* ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’ — Gene Autry

A beloved narrative song that has sold approximately 25 million copies worldwide, cementing the character’s place in Christmas folklore.

Other perennial favourites often in the mix:

* ‘Feliz Navidad’ – José Feliciano

* ‘A Holly Jolly Christmas’ – Burl Ives

* ‘Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!’ – Frank Sinatra

Let me also add that this Thursday’s ‘SceneAround’ feature (25th December) will be a Christmas edition, highlighting special Christmas and New Year messages put together by well-known personalities for readers of The Island.

-

Midweek Review6 days ago

Midweek Review6 days agoHow massive Akuregoda defence complex was built with proceeds from sale of Galle Face land to Shangri-La

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoPope fires broadside: ‘The Holy See won’t be a silent bystander to the grave disparities, injustices, and fundamental human rights violations’

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoPakistan hands over 200 tonnes of humanitarian aid to Lanka

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoUnlocking Sri Lanka’s hidden wealth: A $2 billion mineral opportunity awaits

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoBurnt elephant dies after delayed rescue; activists demand arrests

-

News9 hours ago

News9 hours agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoColombo Port facing strategic neglect

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoArmy engineers set up new Nayaru emergency bridge