Features

Transformations in Sri Lankan social sciences: From early to modern anthropology

by Amarasiri de Silva

Before the 1970s, anthropology in Sri Lanka, as an academic discipline, was relatively confined to a few studies. The country had only a few trained anthropologists, and the scope of anthropological research needed to be expanded. This reflected a broader trend in the social sciences in Sri Lanka, where subjects like sociology and anthropology are still required to be fully institutionalized or widely pursued. However, the discipline began to change significantly in the subsequent decades, particularly with the expansion of the departments of Sociology at major universities in Sri Lanka.

The expansion of the departments of Sociology in Sri Lanka’s universities was a pivotal development in the history of social sciences in the country. This expansion increased the number of students who could study sociology and diversified the subjects and research areas that could be explored within the discipline. Sociology was increasingly offered as a special degree, attracting many students interested in studying the social fabric of the country.

This shift in academic focus led to a significant increase in students pursuing higher education in sociology. After successfully completing their undergraduate degrees, with first and second classes, many of these students pursued advanced degrees, including PhDs, at prestigious universities abroad. The most common destinations for these students were India, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, where they could receive training in the latest methodologies and theoretical frameworks in anthropology and the social sciences.

The exposure to foreign academic environments had a profound impact on the way sociology was studied and practiced in Sri Lankan universities. Students who went abroad for their PhDs were exposed to many theoretical perspectives and research methodologies that they brought back a wealth of knowledge and expertise, which they applied to their research and teaching in Sri Lanka.

One of the most significant contributions of these post 1970 foreign-trained sociologists was their emphasis on empirical research and fieldwork, and applied orientation in research. Unlike earlier generations of sociologists and anthropologists who often relied on theoretical analysis of classical anthropology, these new scholars emphasized the importance of gathering data from the field on social change and social problems. This approach led to a surge in applied anthropological and sociological studies conducted in Sri Lankan villages, as these scholars sought to understand the social dynamics of rural life in the country.

The focus of these studies reflected both the new methodologies introduced to these scholars and the distinct social and cultural landscape of Sri Lanka. With most of the population residing in rural areas, understanding village dynamics was essential to comprehending the broader social fabric of the country. Some scholars concentrated on the intricacies of caste, while others explored the rise of class and its impact on social formation, stratification and political behaviour.

By documenting various aspects of village life—such as kinship structures, economic activities, religious practices, and social hierarchies—their research provided valuable insights into how traditional social structures were being preserved or transformed amid modernization and economic change. Additionally, some researchers turned their attention to marginalized communities, including deprived caste groups and ethnic enclaves, highlighting their unique challenges and contributions to the social structure.

The documentation of village studies also significantly impacted the development of anthropology as a discipline in Sri Lanka. Although many of these scholars identified as sociologists, their research often overlapped with anthropological concerns, particularly in their focus on culture, tradition, and social organization. As a result, the line between sociology and anthropology became increasingly blurred, leading to a more integrated approach to the study of social life in Sri Lanka.

The early anthropological and sociological research conducted in Sri Lanka during this period laid the foundation for future studies. The emphasis on fieldwork and empirical research became a hallmark of Sri Lankan sociology, and many of the methodologies and theoretical perspectives introduced by these scholars continue to influence research in the country today.

Moreover, the focus on village studies has impacted how rural life is understood in Sri Lanka. The detailed documentation of village life has provided a valuable record of the social and cultural changes that have occurred in the country over the past few decades. These studies have also contributed to a deeper understanding of how global processes, such as economic development and cultural exchange, have impacted local communities in Sri Lanka.

My Exposure to Anthropological Fieldwork

My journey into the world of anthropology began during my master’s degree research in Mirissa, a fishing village located in the southern province of Sri Lanka. Having been born and raised in an agricultural village, Batapola in the Galle District, my exposure to the coastal environment of Mirissa was an entirely new and transformative experience.

The transition from an agricultural backdrop to a coastal fishing community presented a set of unique challenges that I had never encountered before. In Mirissa, I was introduced to the intricacies of various fishing methods, a completely different form of livelihood compared to the farming practices I was familiar with. Learning about the techniques used in the capture of fish, the handling and processing of the catch, and the complex networks involved in fish marketing, crew formation, etc., required me to immerse myself deeply into the everyday lives of the villagers.

Beyond the technical aspects, understanding the lives of the fishermen and their families offered profound insights into the social fabric of coastal communities. I observed how the rhythms of life in Mirissa were intimately tied to the sea, shaping the village’s economy and the community’s cultural and social structures. The challenges faced by these families, their resilience, and how they navigated the uncertainties of their occupation became focal points of my research.

This experience in Mirissa not only broadened my understanding of Sri Lanka’s diverse socio-economic landscapes but also deepened my appreciation for the complexity and richness of anthropological research. Through this fieldwork, I realized the importance of adapting to new environments and the necessity of approaching research with sensitivity and respect for the communities involved.

One of the challenges I encountered during my research in Mirissa was establishing the parameters of social change in Mirissa, particularly with the introduction of mechanized boats, or the three-and-a-half-ton boats, which began to replace the traditional outrigger canoes with sails. It quickly became apparent that this technological shift was not merely a matter of economic or practical change but had profound social implications for the village. When mechanized boats were first introduced in the 1950s, the villagers were skeptical about the viability of this new technology. Some recipients even destroyed the freely given boats by submerging them in the sea. Out of the roughly 40 boats distributed to the deep-sea fishing community, only one remained operational at the time of my research. The others were either sold or damaged.

I observed that the village was divided into distinct social categories, based on the method of fishing. Some fished in the deep sea using mechanized boats or canoes (Ruwal oru), and those engaged in shallow sea fishing using beach seine nets (Ma Dal). These two communities, within the village, were highly divergent, with a strong sense of identity tied to their respective fishing practices.

The social divide between these groups was evident not only in their daily activities but also in their social interactions. Intermarriage between the two communities was rare, a reflection of the deep-seated cultural and social differences that had developed over time. Additionally, this division was spatially manifested within the village itself. The deep-sea fishermen resided by the sea in an area known as Badugoda, where they had easy access to the ocean. In contrast, the beach seine fishermen lived by the main road, a location that offered them convenient access to the beaches allocated for their fishing practices.

This geographical separation further reinforced the social boundaries between the two groups, creating distinct sections within the village, each with its traditions, practices, and way of life. Understanding this complex social landscape was crucial to my research, as it highlighted the intricate ways technological and economic changes can influence social structures and relationships within a community.

I commenced my research in the beach seine section of the village in the early 1970s. Through a mutual friend, I was introduced to Mr. Nilaweera, a schoolteacher in the village. Mr. Nilaweera played a pivotal role in helping me settle into the community. He assisted me in finding a place to live—an empty house with basic furniture that he kindly provided. Understanding the challenges of living alone in a new environment, Mr. Nilaweera also arranged for an older woman to cook for me. She prepared delicious meals, often including fresh fish caught in the beach seine nets, or embul thiyal using Alagodu maalu which added to the authenticity of my experience.

To further support my research, Mr. Nilaweera introduced me to two key informants—one from the beach seine fishing community, near Mr. Nilaweera’s house, and the other from the deep-sea fishing community in Badugoda. These informants were invaluable to my work; both were highly knowledgeable and willing to share their insights. They patiently answered all my questions, explaining even the minutest details about the village’s social dynamics, fishing practices, and the distinctions between the two communities. Their guidance was instrumental in deepening my understanding of Mirissa’s complex social fabric.

Mr. Gilbert Weerasuriya, the informant from the beach seine community, possessed knowledge far surpassed that of many average villagers. He provided me with a detailed account of how beach seine nets were introduced to the village and traced the history of their evolution. He explained the traditional method of fishing, using these nets, describing how fish were caught by encircling shoals near the shore.

The first nets were made of coir and coconut leaves, which later used hemp thread to make the nets. The madiya, or the deep end of the net where the fish gets caught, is woven with hemp, while the side nets were made with coir lines.

Later in the 1950s nylon was introduced for beach seine nets, and the catch doubled with the new nets. According to him, the beach seine canoe fishermen originally came from the Coromandel Coast, in India, and eventually settled in beach communities, like Negombo and Mirissa, in Sri Lanka. He noted that similar fishing practices can also be found in coastal communities across India. Interestingly, the early beach seiners in these Sri Lankan communities spoke an Indian language, like Telugu, remnants of which were still present in the songs they sing while hauling the seine nets.

My search in the archives revealed that villagers in and around Mirissa had names ending in “Naide,” a corrupted form of an Indian name. In India, particularly in regions like Maharashtra or Karnataka, “Naide” could be a variant or misspelling of the surname “Naidu,” common among Telugu-speaking people. These family names can be found in school thomboos maintained by the Dutch.

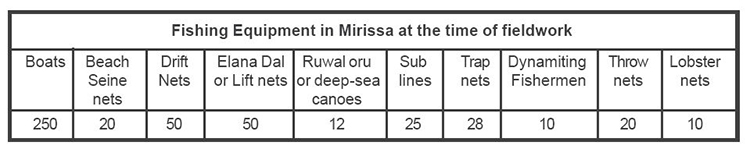

In 1948, at Mirissa, there were only three groups of fishermen: beach seine fishermen, deep sea fishermen, and inshore fishermen. The total number of seine nets in 1947 was 242, owned by a group of 108 fishermen. The deep-sea canoes numbered around 50, operated by about 150 people. Inshore fishing was done in small dugout canoes known as Kuda Oru, with about 20 of them at that time. When I conducted my fieldwork, the numbers had dwindled. There were only six beach seine nets, about 50 deep sea fishermen operated boats and a few Kuda Oru operated by a handful of fishermen.

The process of beach seine fishing involved a large canoe that carried the nets out to sea. The fishermen would then lay the nets in a half-circle, encircling the shoal of fish. Once the nets were in place, the two ends of the circled net were handed over to two groups of fishermen, who began hauling the nets from the shore. At the centre of this operation was the lead fisherman, known as the “mannadirala,” who directed the entire process. The mannadirala would give precise instructions to the hauling groups, ensuring that they drew the net at a specific speed to prevent the fish from escaping through the net. His role was crucial, as the success of the catch depended on the mannalirala’s expertise in coordinating the efforts of the fishermen and controlling the net’s movement.

The beach seine net is owned in shares by various people in the village, and the shoal of fish brought to shore is distributed according to these share ownerships. One-fourth of the catch is allocated to the crew members, known as the “thandukarayo,” (rowers or peddlers) who undertake the challenging task of going out in the canoe to encircle the shoal of fish. Another one-fourth is given to the fishermen responsible for hauling the net at the two ends. A third portion is allocated to the individuals responsible for maintaining the net and the canoe.

The remaining portion is then divided among the shareholders. This division of shares occurs in monetary terms after the fish is sold to vendors and merchants in a process known as “vendesiya.” Additionally, it’s customary for every villager who participated in the fishing activity, even if they are not shareholders, to receive a few fish as a token of appreciation for their contribution. After the fish haul is taken to the shore, people like the mannadirala sort out the fish, separating the big ones from others, like sprats/anchovies or harmless fish. Fish suitable for the family, such as those beneficial for breastfeeding mothers, like kiri boollo, were taken home by the mannadirala and other key individuals.

I was particularly interested in tracing the history of deep-sea canoes, and my interviews with the key informant from the deep-sea fishing community proved invaluable in this regard. This informant, whose knowledge and wisdom were so widely respected that the villagers called him “Soulbury Sami” (Lord Soulbury), was a central figure in the community. Deep-sea fishermen frequently sought his advice on fishing grounds (hantan) and other aspects of deep-sea fishing.

One of the key questions I posed to him was about the number of canoes used for deep-sea fishing before the introduction of mechanized boats. His response was both simple and ingenious. Squatting on the beach, he explained that he could vividly recall who had parked their canoes on his deep-sea canoe’s right and left sides. He took a stick and drew the canoe the family-owned, saying, “This was our oruwa.” Then he drew two similar canoes on each side of his canoe drawn on the beach and said, “I can tell you who owned these two canoes parked beside ours.” He then suggested that I use this method as a starting point. By asking the families who had parked their canoes beside his about their neighbouring canoes, I could piece together a complete picture of the canoe ownership at that time.

This method was remarkably effective. By following his advice and speaking with the families involved, I eventually compiled a list of 48 canoes parked on the beach during the 1940s. This simple yet systematic approach gave me a clear and comprehensive understanding of the deep-sea fishing community’s history before the advent of mechanized boats.

Mirissa has now transformed from a quiet fishing village into a vibrant tourist hub over the past few decades. Once known for its beach seine fishing traditions, the village of Mirissa has evolved significantly over time. The introduction of three-and-a-half-ton boats and trollers modernized its fishing industry, moving the community from traditional fishing methods to more advanced deep-sea fishing. However, over the years, tourism has gradually overtaken fishing as the primary source of livelihood for many villagers. This shift highlights the community’s remarkable adaptability in embracing new opportunities, transforming from a primarily fishing-based economy into a thriving tourist destination.

This small but picturesque destination now boasts over a hundred hotels and boutique accommodations, offering various lodging options for visitors from all over the world. The trajectory of change and transition from being a fishing community focused on beach seine techniques—where nets were dragged ashore by hand—to deep-sea fishing and ultimately to tourism is remarkable. Today, Mirissa is known not for its fishing but for its breathtaking beaches, lush greenery, and panoramic views, making it a must-visit destination in Sri Lanka.

Mirissa’s natural beauty is complemented by an array of activities that attract adventure enthusiasts and nature lovers alike. Whale watching has become one of the village’s most prominent draws, with local boat operators offering tours where visitors can witness the magnificent blue whales, sperm whales, and dolphins in their natural habitat. Additionally, surfing and snorkeling are among the key attractions.

Tourism has brought prosperity to the local community, which depends less on traditional fishing and more on hospitality and tourism services. Many locals earn their livelihoods by operating guesthouses, hotels, and restaurants or by offering services like guided boat tours for whale watching, renting surfboards, and providing transportation for tourists. The once-close connection to the sea, driven by fishing, is now maintained through tourism, as the ocean remains central to the lives of the villagers, albeit in a different way.

Mirissa’s development into a tourist village has not only created economic opportunities. Still, it has also become a cultural melting pot where visitors can experience authentic Sri Lankan traditions, cuisine such as embul thiyal alongside the comforts of modern urban foods. This seamless blend of natural beauty, adventure, and cultural richness makes Mirissa a unique and beloved destination for travellers worldwide.

Features

A plural society requires plural governance

The local government elections that took place last week saw a consolidation of the democratic system in the country. The government followed the rules of elections to a greater extent than its recent predecessors some of whom continue to be active on the political stage. Particularly noteworthy was the absence of the large-scale abuse of state resources, both media and financial, which had become normalised under successive governments in the past four decades. Reports by independent election monitoring organisations made mention of this improvement in the country’s democratic culture.

In a world where democracy is under siege even in long-established democracies, Sri Lanka’s improvement in electoral integrity is cause for optimism. It also offers a reminder that democracy is always a work in progress, ever vulnerable to erosion and needs to be constantly fought for. The strengthening of faith in democracy as a result of these elections is encouraging. The satisfaction expressed by the political parties that contested the elections is a sign that democracy in Sri Lanka is strong. Most of them saw some improvement in their positions from which they took reassurance about their respective futures.

The local government elections also confirmed that the NPP and its core comprising the JVP are no longer at the fringes of the polity. The NPP has established itself as a mainstream party with an all-island presence, and remarkably so to a greater extent than any other political party. This was seen at the general elections, where the NPP won a majority of seats in 21 of the country’s 22 electoral districts. This was a feat no other political party has ever done. This is also a success that is challenging to replicate. At the present local government elections, the NPP was successful in retaining its all-island presence although not to the same degree.

Consolidating Support

Much attention has been given to the relative decline in the ruling party’s vote share from the 61 percent it secured in December’s general election to 43 percent in the local elections. This slippage has been interpreted by some as a sign of waning popularity. However, such a reading overlooks the broader trajectory of political change. Just three years ago, the NPP and its allied parties polled less than five percent nationally. That they now command over 40 percent of the vote represents a profound transformation in voter preferences and political culture. What is even more significant is the stability of this support base, which now surpasses that of any rival. The votes obtained by the NPP at these elections were double those of its nearest rival.

The electoral outcomes in the north and east, which were largely won by parties representing the Tamil and Muslim communities, is a warning signal that ethnic conflict lurks beneath the surface. The success of the minority parties signals the different needs and aspirations of the ethnic and religious minority electorates, and the need for the government to engage more fully with them. Apart from the problems of poverty, lack of development, inadequate access to economic resources and antipathy to excessive corruption that people of the north and east share in common with those in other parts of the country, they also have special problems that other sections of the population do not have. These would include problems of military takeover of their lands, missing persons and persons incarcerated for long periods either without trial or convictions under the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act (which permits confessions made to security forces to be made admissible for purposes of conviction) and the long time quest for self-rule in the areas of their predominance

The government’s failure to address these longstanding issues with urgency appears to have caused disaffection in electorate in the north and east. While structural change is necessarily complex and slow, delays can be misinterpreted as disinterest or disregard, especially by minorities already accustomed to marginalisation. The lack of visible progress on issues central to minority communities fosters a sense of exclusion and deepens political divides. Even so, it is worth noting that the NPP’s vote in the north and east was not insignificant. It came despite the NPP not tailoring its message to ethnic grievances. The NPP has presented a vision of national reform grounded in shared values of justice, accountability, development, and equality.

Translating electoral gains into meaningful governance will require more than slogans. The failure to swiftly address matters deemed to be important by the people of those areas appears to have cost the NPP votes amongst the ethnic and religious minorities, but even here it is necessary to keep matters in perspective. The NPP came first in terms of seats won in two of the seven electoral districts of the north and east. They came second in five others. The fact that the NPP continued to win significant support indicates that its approach of equity in development and equal rights for all has resonance. This was despite the Tamil and Muslim parties making appeals to the electorate on nationalist or ethnic grounds.

Slow Change

Whether in the north and east or outside it, the government is perceived to be slow in delivering on its promises. In the context of the promise of system change, it can be appreciated that such a change will be resisted tooth and nail by those with vested interests in the continuation of the old system. System change will invariably be resisted at multiple levels. The problem is that the slow pace of change may be seen by ethnic and religious minorities as being due to the disregard of their interests. However, the system change is coming slow not only in the north and east, but also in the entire country.

At the general election in December last year, the NPP won an unprecedented number of parliamentary seats in both the country as well as in the north and east. But it has still to make use of its 2/3 majority to make the changes that its super majority permits it to do. With control of 267 out of 339 local councils, but without outright majorities in most, it must now engage in coalition-building and consensus-seeking if it wishes to govern at the local level. This will be a challenge for a party whose identity has long been built on principled opposition to elite patronage, corruption and abuse of power rather than to governance. General Secretary of the JVP, Tilvin Silva, has signaled a reluctance to form alliances with discredited parties but has expressed openness to working with independent candidates who share the party’s values. This position can and should be extended, especially in the north and east, to include political formations that represent minority communities and have remained outside the tainted mainstream.

In a plural and multi-ethnic society like Sri Lanka, democratic legitimacy and effective governance requires coalition-building. By engaging with locally legitimate minority parties, especially in the north and east, the NPP can engage in principled governance without compromising its core values. This needs to be extended to the local government authorities in the rest of the country as well. As the 19th century English political philosopher John Stuart Mill observed, “The worth of a state in the long run is the worth of the individuals composing it,” and in plural societies, that worth can only be realised through inclusive decision-making.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Commercialising research in Sri Lanka – not really the healthiest thing for research

In the early 2000s, a colleague, returning to Sri Lanka after a decade in a research-heavy first world university, complained to me that ‘there is no research culture in Sri Lanka’. But what exactly does having a ‘research culture’ mean? Is a lot of funding enough? What else has stopped us from working towards a productive and meaningful research culture? A concerted effort has been made to improve the research culture of state universities, though there are debates about how healthy such practices are (there is not much consideration of the same in private ‘universities’ in Sri Lanka but that is a discussion for another time). So, in the 25 years since my colleague bemoaned our situation, what has been happening?

What is a ‘research culture’?

A good research culture would be one where we – academics and students – have the resources to engage productively in research. This would mean infrastructure, training, wholesome mentoring, and that abstract thing called headspace. In a previous Kuppi column, I explained at length some of the issues we face as researchers in Sri Lankan universities, including outdated administrative regulations, poor financial resources, and such aspects. My perspective is from the social sciences, and might be different to other disciplines. Still, I feel that there are at least a few major problems that we all face.

Number one: Money is important.

Take the example American universities. Harvard University, according to Harvard Magazine, “received $686.5 million in federally sponsored research grants” for the fiscal year of 2024 but suddenly find themselves in a bind because of such funds being held back. Research funds in these universities typically goes towards building and maintenance of research labs and institutions, costs of equipment, material and other resources and stipends for graduate and other research assistants, conferences, etc. Without such an infusion of money towards research, the USA would not have been able to attracts (and keeps) the talent and brains of other countries. Without a large amount of money dedicated for research, Sri Lankan state universities, too, will not have the research culture it yearns for. Given the country’s austere economic situation, in the last several years, research funds have come mainly from self-generated funds and treasury funds. Yet, even when research funds are available (they are usually inadequate), we still have some additional problems.

Number two: Unending spools of red tape

In Sri Lankan universities red tape is endless. An MoU with a foreign research institution takes at least a year. Financial regulations surrounding the award and spending of research grants is frustrating.

Here’s a personal anecdote. In 2018, I applied for a small research grant from my university. Several months later, I was told I had been awarded it. It comes to me in installments of not more than Rs 100,000. To receive this installment, I must submit a voucher and wait a few weeks until it passes through various offices and gains various approvals. For mysterious financial reasons, asking for reimbursements is discouraged. Obviously then, if I were working on a time-sensitive study or if I needed a larger amount of money for equipment or research material, I would not be able to use this grant. MY research assistants, transcribers, etc., must be willing to wait for their payments until I receive this advance. In 2022, when I received a second advance, the red tape was even tighter. I was asked to spend the funds and settle accounts – within three weeks. ‘Should I ask my research assistants to do the work and wait a few weeks or months for payment? Or should I ask them not to do work until I get the advance and then finish it within three weeks so I can settle this advance?’ I asked in frustration.

Colleagues, who regularly use university grants, frustratedly go along with it; others may opt to work with organisations outside the university. At a university meeting, a few years ago, set up specifically to discuss how young researchers could be encouraged to do research, a group of senior researchers ended the meeting with a list of administrative and financial problems that need to be resolved if we want to foster ‘a research culture’. These are still unresolved. Here is where academic unions can intervene, though they seem to be more focused on salaries, permits and school quotas. If research is part of an academic’s role and responsibility, a research-friendly academic environment is not a privilege, but a labour issue and also impinges on academic freedom to generate new knowledge.

Number three: Instrumentalist research – a global epidemic

The quality of research is a growing concern, in Sri Lanka and globally. The competitiveness of the global research environment has produced seriously problematic phenomena, such as siphoning funding to ‘trendy’ topics, the predatory publications, predatory conferences, journal paper mills, publications with fake data, etc. Plagiarism, ghost writing and the unethical use of AI products are additional contemporary problems. In Sri Lanka, too, we can observe researchers publishing very fast – doing short studies, trying to publish quickly by sending articles to predatory journals, sending the same article to multiple journals at the same time, etc. Universities want more conferences rather than better conferences. Many universities in Sri Lanka have mandated that their doctoral candidates must publish journal articles before their thesis submission. As a consequence, novice researchers frequently fall prey to predatory journals. Universities have also encouraged faculties or departments to establish journals, which frequently have sub-par peer review.

Alongside this are short-sighted institutional changes. University Business Liankage cells, for instance, were established as part of the last World Bank loan cycle to universities. They are expected to help ‘commercialise’ research and focuses on research that can produce patents, and things that can be sold. Such narrow vision means that the broad swathe of research that is undertaken in universities are unseen and ignored, especially in the humanities and social sciences. A much larger vision could have undertaken the promotion of research rather than commercialisation of it, which can then extend to other types of research.

This brings us to the issue of what types of research is seen as ‘relevant’ or ‘useful’. This is a question that has significant repercussions. In one sense, research is an elitist endeavour. We assume that the public should trust us that public funds assigned for research will be spent on worth-while projects. Yet, not all research has an outcome that shows its worth or timeliness in the short term. Some research may not be understood other than by specialists. Therefore, funds, or time spent on some research projects, are not valued, and might seem a waste, or a privilege, until and unless a need for that knowledge suddenly arises.

A short example suffices. Since the 1970s, research on the structures of Sinhala and Sri Lankan Tamil languages (sound patterns, sentence structures of the spoken versions, etc.) have been nearly at a standstill. The interest in these topics are less, and expertise in these areas were not prioritised in the last 30 years. After all, it is not an area that can produce lucrative patents or obvious contributions to the nation’s development. But with digital technology and AI upon us, the need for systematic knowledge of these languages is sorely evident – digital technologies must be able to work in local languages to become useful to whole populations. Without a knowledge of the structures and sounds of local languages – especially the spoken varieties – people who cannot use English cannot use those devices and platforms. While providing impetus to research such structures, this need also validates utilitarian research.

This then is the problem with espousing instrumental ideologies of research. World Bank policies encourage a tying up between research and the country’s development goals. However, in a country like ours, where state policies are tied to election manifestos, the result is a set of research outputs that are tied to election cycles. If in 2019, the priority was national security, in 2025, it can be ‘Clean Sri Lanka’. Prioritising research linked to short-sighted visions of national development gains us little in the longer-term. At the same time, applying for competitive research grants internationally, which may have research agendas that are not nationally relevant, is problematic. These are issues of research ethics as well.

Concluding thoughts

In moving towards a ‘good research culture’, Sri Lankan state universities have fallen into the trap of adopting some of the problematic trends that have swept through the first world. Yet, since we are behind the times anyway, it is possible for us to see the damaging consequences of those issues, and to adopt the more fruitful processes. A slower, considerate approach to research priorities would be useful for Sri Lanka at this point. It is also a time for collective action to build a better research environment, looking at new relationships and collaborations, and mentoring in caring ways.

(Dr. Kaushalya Perera teaches at the Department of English, University of Colombo)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Kaushalya Perera

Features

Melantha …in the spotlight

Melantha Perera, who has been associated with many top bands in the past, due to his versatility as a musician, is now enjoying his solo career, as well … as a singer.

Melantha Perera, who has been associated with many top bands in the past, due to his versatility as a musician, is now enjoying his solo career, as well … as a singer.

He was invited to perform at the first ever ‘Noon2Moon’ event, held in Dubai, at The Huddle, CityMax Hotel, on Saturday, 3rd May.

It was 15 hours of non-stop music, featuring several artistes, with Melantha (the only Sri Lankan on the show), doing two sets.

According to reports coming my way, ‘Noon2Moon’ turned out to be the party of the year, with guests staying back till well past 3.00 am, although it was a 12.00 noon to 3.00 am event.

Having Arabic food

Melantha says he enjoyed every minute he spent on stage as the crowd, made up mostly of Indians, loved the setup.

“I included a few Sinhala songs as there were some Sri Lankans, as well, in the scene.”

Allwyn H. Stephen, who is based in the UAE, was overjoyed with the success of ‘Noon2Moon’.

Says Allwyn: “The 1st ever Noon2Moon event in Dubai … yes, we delivered as promised. Thank you to the artistes for the fab entertainment, the staff of The Huddle UAE , the sound engineers, our sponsors, my supporters for sharing and supporting and, most importantly, all those who attended and stayed back till way past 3.00 am.”

Melantha:

Dubai and

then Oman

Allwyn, by the way, came into the showbiz scene, in a big way, when he featured artistes, live on social media, in a programme called TNGlive, during the Covid-19 pandemic.

After his performance in Dubai, Melantha went over to Oman and was involved in a workshop – ‘Workshop with Melantha Perera’, organised by Clifford De Silva, CEO of Music Connection.

The Workshop included guitar, keyboard and singing/vocal training, with hands-on guidance from the legendary Melantha Perera, as stated by the sponsors, Music Connection.

Back in Colombo, Melantha will team up with his band Black Jackets for their regular dates at the Hilton, on Fridays and Sundays, and on Tuesdays and Thursdays at Warehouse, Vauxhall Street.

Melantha also mentioned that Bright Light, Sri Lanka’s first musical band formed entirely by visually impaired youngsters, will give their maiden public performance on 7th June at the MJF Centre Auditorium in Katubadda, Moratuwa.

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSAITM Graduates Overcome Adversity, Excel Despite Challenges

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoNPP win Maharagama Urban Council

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoJohn Keells Properties and MullenLowe unveil “Minutes Away”

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoASBC Asian U22 and Youth Boxing Championships from Monday

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoDestined to be pope:Brother says Leo XIV always wanted to be a priest

-

Foreign News4 days ago

Foreign News4 days agoMexico sues Google over ‘Gulf of America’ name change

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoRatmalana: An international airport without modern navigational and landing aids

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoDrs. Navaratnam’s consultation fee three rupees NOT Rs. 300