Features

The Wijeweera Legacy and Left Prospects Today

by Dr. Dayan Jayatilleka

The Left in Sri Lanka is closer than it has ever been to leading the country. This is borne out by public opinion polling which consistently puts Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD) the JVP-NPP leader ahead of the competition at a presidential election and his party or bloc, the NPP-JVP ahead of the competition at a parliamentary election.

The mystery is that AKD and the JVP-NPP aren’t doing everything it can, or even the minimum things it can, to increase its slim lead and get to the magic 50% mark. In every other situation everywhere in the world in which the Left has come within striking distance of electoral victory, or indeed victory of any sort, the natural reflex has been to seek to close the gap through tweaking its own policies and profile so as to elasticize its appeal while reaching out and building political partnerships, alliances, blocs, in a word, political relationships, that bring it home to victory.

This has been the lesson of Pink Tide one and two which has seen the democratic Left sweep Latin America twice in the past quarter century. It has also been the experience of the Marxist-Leninist left in Nepal.

That is precisely what the JVP-NPP is not doing. I was discussing this paradox with an incisive young friend who earned a postgraduate degree in international relations in a First World university before he became the business magnate he is. “If the JVP and the FSP united it would give rise to brilliant synergy, but the JVP believes in competitive advantage, not cooperative advantage. It would rather lose, persisting in comparative advantage than win, switching to cooperative advantage” he opined.

Political Genetics

Where did this self-limitation, this chronic inability to form inter-party/cross-party political relationships come from? Why is it persisted in even at the risk of losing the elections?

More puzzling, why is it indulged in even though it prevents the JVP-NPP’s ability to wrench an election from the reluctant Ranil Wickremesinghe?

Why is it adhered to even though it hamstrings, the JVP-NPP’s ability to protect its trade unions from the vicious labor legislation that is imminent, and/or the sell-off of the state sector of the economy which houses many of those unions?

The reason, the cause, lies in the genetic structure, the genetic code of the JVP. Those political-ideological genes are the source of the JVP’s strength and its weakness. To seek the real reason, one has to return to the JVP’s roots; its paternity.

Rohana Wijeweera was the most significant or consequential left leader this island ever produced. He grasped what Georg Lukacs, writing of Lenin, described as “the actuality of the revolution”. Though he had several contemporaries who had the same idea and strivings, without Wijeweera, revolution would never really have come on the agenda of Sri Lankan history. His real strength was a combination of two attributes. Firstly, the ability to apply and adapt—which in his case, tragically involved great distortion—Marxism-Leninism to the specifics of the Sri Lankan reality and the sociology of the underprivileged Lankan youth. Secondly, the ability to organize and instill in his followers the zeal to organize.

No Wijeweera, no JVP; no JVP, no real challenge to the Sri Lankan capitalist system and capitalist class. No Wijeweera, no real challenge to the Sri Lankan state. No JVP, no FSP offshoot, and no really effective Left on the island. No effective Left, no alternative or counterbalance to the capitalist politicians or the savage neoliberal cutbacks. No JVP and FSP and no counterforce, or even voice, for the disadvantaged masses, the youth from the poorer classes and generations educated in the state universities.

There is a flipside, or as they say, the matter needs a dialectical approach. If not for Wijeweera’s strengths, no JVP challenge to the System, but if not for Wijeweera’s weaknesses, those challenges would not have been so distorted as be successfully beaten down. Look at the track record. Two significant armed uprisings, both smashed militarily, punctuated and followed by desultory-to-modest electoral performance so far.

Compare and contrast that with Latin America where the Left either managed to use its military strength to force negotiations and the re-opening of the system which permitted electoral participation culminating in victory and re-election, or even in cases of utter military devastation, retained enough of a moral-ethical halo, to win Presidential elections.

What is the reason? While Wijeweera’s strength lent the JVP determination and resilience, his chronic weaknesses also imposed structural limits on its success. His paranoia made him see any competitor or dissenter as an enemy who had to be dealt with violently. This aborted any possibility of united fronts, alliances, and blocs, i.e., any partnership or more plainly, political relationships. It was a self-fulfilling prophecy. The enemies he and the JVP made on the Left through lethal violence, turned out to be the decisive factor in the JVP’s crushing military defeat in 1989.

This paranoia, though in a greatly reduced form, has been carried on to the next generation through the JVP’s DNA. It is mercifully, far more diluted in the breakaway FSP. However, the FSP, while much less sectarian, is not entirely immune either. In a Southern European or Latin American context, an FSP-type party would have united either with other left parties (that’s how Syriza and Podemos were formed) or worked within the SJB and/or FPC.

Tamil Question

Wijeweera had a chronic inability to formulate a Marxist solution to the Tamil National Question—that is, apart from writing a 350-page book (his report to the underground party Congress in 1985) which had more consecutive pages criticizing me by name than Velupillai Prabhakaran.

Though the JVP and FSP have abandoned his ‘social chauvinism’ – which Wimal Weerawansa is continuing – and are laudably anti-racist parties, they too have baulked at embracing the standard Marxist and Left formulation of ‘regional autonomy’. Instead, the JVP wobbles while the FSP still flirts occasionally with ‘self-determination’ – which Wijeweera was correct to reject and I was wrong not to. The result of this Wijeweera legacy has been a political paralysis of both the JVP and the FSP on the Tamil Question which prevents any kind of North-South political bridge-building or even an extended conversation.

Surplus Violence

Electorally, the biggest liability of the Wijeweera period is the character of the violence of the second uprising in the late 1980s. Both the JVP and the FSP have been unable to get beyond the old justificatory narrative of “the UNP framed us and banned us, so we had no choice but to fight back”. That narrative is often supplemented with “the Indians projected power onto our soil so we had to resist it arms in hand”.

Taken separately or together, the justificatory narrative fails to deal with the issue of barbarism as manifested in targeting. What does the UNP’s ban on the JVP or the Indian airdrop and the Accord have to do with the very first political assassination by the JVP in the 1980s, namely the slitting of the throat of Daya Pathirana, the leader of the radical left Independent Students Union, who had signed a petition in 1984 calling for the removal of the ban on the JVP, and was murdered on December 15, 1986, many months before the Indian intervention?

The problem is not with the JVP taking up arms but the use those arms were put to. Is there no way for the JVP and the breakaway FSP to reaffirm the legitimacy of its recourse to arms with a self-criticism of the lethal targeting of unarmed rivals and non-compliant civilians targeting which made bitter enemies of other radical leftists who then proved to be the critical variable in the JVP’s defeat? Why not a self-criticism of the needless and ultimately suicidal decision to continue or resume the civil war when a real chance had arisen to negotiate an honourable solution and even enter the government when the newly-elected, non-elite, populist President Premadasa invited it to do so?

The failure to make a public self-criticism about aspects of its armed struggle reduces the level of public trust that the JVP-NPP could otherwise count on because of the economic crisis. In some areas there are horrific memories of JVP violence and persecution of the people (snatching ID

cards, imposing curfews, strictures on funerals etc.). These votes could comprise the margin of victory or defeat and yet the JVP is unwilling to do its due diligence to secure them.

Erasing Theory

Finally, there is the perhaps the most important drawback of the Wijeweera legacy that the JVP and FSP share, and should cut clean away from if the Left is to win or even survive Ranil’s counter-revolutionary offensive.

After 1973 or perhaps 1976, Rohana Wijeweera sealed the JVP off from the rich, complex legacy, theoretical and strategic, of the post-Lenin international communist and revolutionary movement. It happened this way. After the defeat of the April 1971 insurrection the incarcerated JVP cadres and those underground and on the run began to read. The reading led to calls for self-criticism and efforts at self-criticism. These were met with violence directed at the dissenters by Wijeweera’s faithful in the jails.

Being the very smart guy he was, Wijeweera knew this was not enough. He then engaged in a massive diversion operation. He diverted attention to the support extended to the Bandaranaike government by the ruling Communist parties of Russia and more dramatically China and went on a huge binge against the international communist movement. His lawyer the celebrated Trotskyist Bala Tampoe was giving him considerable reading material, chiefly the writings of Ernest Mandel.

Ever the utilitarian, Wijeweera switched from his 1973 position of endorsing independent-minded Communist parties non-aligned between Russia and China, i.e., Cuba, Vietnam, North Korea, Japan, and the Communist Party of India-Marxist, to a complete rupture which took the Trotskyist position that international communism had been incorrupt only up to the first four Congresses of the Communist International (Comintern). In short, it pretty much had all gone wrong after Lenin, except for the positions of the ‘Left Opposition’ (Trotsky, Zinoviev, Radek, Preobrazhensky) against Stalin.

Wijeweera being Wijeweera, he dumped this ‘ultra-internationalism’ when the party was unfairly banned by the UNP and went underground. He then switched to its opposite position, adopting ultra nationalism in his 1985 book, denouncing any and every form of political devolution down to the District Development Councils which the JVP had itself contested.

Original Sin

What is most pertinent to the situation today, is that in order to facilitate a free hand for himself to swing from one position to its opposite, Wijeweera maintained the cut-off point at Lenin and there too, suppressing his ‘Two Tactics’ (1905). This meant that decades of Marxist and revolutionary thought after Lenin was de-legitimized, denounced, or ignored; unavailable to and discouraged among JVP leaders and members. Wijeweera reserved for himself the right to toss in the names of Fidel, Che, Miguel Enriquez (founder of the Chilean MIR) et al, without ever quoting at length from them, still less discussing, debating and assimilating their ideas. It was simply name-dropping.

Mao, Gramsci, Dimitrov, Togliatti, Ho Chi Minh, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Amilcar Cabral, Carlos Fonseca, Joe Slovo. None of these were read at length or discussed in depth. The entire conceptualization of United Fronts and the Popular Front, in their many variations, was effaced.

This is the real reason that the JVP does not engage in united fronts with other political parties. This is the real reason the JVP will be mentally unable to do so until it exorcises this ghost of the negative side of Wijeweera’s political paternity.

The treasure house of Marxist thought was shut to the JVP by Wijeweera and never really reopened by him or his successors. The FSP is much more open but it is like the man who escaped Plato’s cave and is blinking in the sunlight. As Plato explained, in a reference to the fate of Socrates, when such an escapee goes back to his fellow prisoners and tries to explain the outside world to them, they are likely to kill him because all they know are the shadows flickering on the walls of the cave.

Meanwhile, the badly defeated Latin American left was deeply studying Gramsci, supplemented by Althusser and Poulantzas. That was the secret of its successful comeback. Though some of those parties had been founded after the JVP and defeated militarily, they were elected to the presidency in their countries well before the JVP found its political and electoral feet.

[Dayan Jayatilleka is author of ‘The Great Gramsci: Imagining an Alt-Left Project’, in On Public Imagination: A Political and Ethical Imperative, eds. Richard Falk et al, Routledge 2019]

Features

International Women’s Day spurs re-visit of unresolved issues

‘Bread and Peace’. This was a stirring demand taken up by Russia’s working women, we are told, in 1917; the year the world’s first proletarian revolution shook Russia and ushered in historic changes to the international political order. The demand continues to be profoundly important for the world to date.

‘Bread and Peace’. This was a stirring demand taken up by Russia’s working women, we are told, in 1917; the year the world’s first proletarian revolution shook Russia and ushered in historic changes to the international political order. The demand continues to be profoundly important for the world to date.

International Women’s Day (IWD) is continuing to be celebrated the world over, come March, but in Sri Lanka very little progress has been achieved over the years by way of women’s empowerment, despite Sri Lanka being a signatory to the UN Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and other pieces of global and local legislation that promise a better lot for women.

The lingering problems in this connection were disturbingly underscored recently by the rape-assault on a female doctor within her consultation chamber at a prominent hospital in Sri Lanka’s North Central Province; to cite just one recent instance of women’s unresolved vulnerability and powerlessness.

The Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies, Colombo (BCIS) came to the forefront in taking up the above and other questions of relevance to women at a forum conducted at its auditorium on March 7th, in view of IWD. The program was organized by the library team at the BCIS, under the guidance of the BCIS Executive Director Priyanthi Fernando.

It was heartening to note that the event was widely attended by schoolchildren on the invitation of the BCIS, besides members of the public, considering that the awareness among the young needs to be consistently heightened and broadened on the principal issue of gender justice. Hopefully, going forward, the young would champion the cause of women’s rights having gained by the insights which have been surfaced by forums such as that conducted by the BCIS.

The panelists at the BCIS forum comprised Kumudini Samuel of the Women and Media Collective, a local organization which is in the forefront of taking up women’s issues, and Raaya Gomez, an Attorney-at-Law, engaged in women’s rights advocacy. Together they gave the audience much to think about on what needs to be done in the field of gender justice and linked questions.

The currently raging wars and conflicts worldwide ought to underscore as never before, the yet to be substantively addressed vulnerability of women and children and the absolute need for their consistent empowerment. It is plain to see that in the Gaza, for example, it is women and children who are put through the most horrendous suffering.

Yet, women are the sole care-givers and veritable bread winners of their families in particularly times of turmoil. Their suffering and labour go unappreciated and unquantified and this has been so right through history. Conventional economics makes no mention of the contribution of women towards a country’s GDP through their unrecorded labour and, among other things, this glaring wrong needs to be righted.

While pointing to the need for ‘Bread and Peace’ and their continuing relevance, Kumudini Samuel made an elaborate presentation on the women’s struggle for justice and equality in Sri Lanka over the decades. Besides being the first country to endow women with the right to vote in South Asia, Sri Lanka has been in the forefront of the struggle for the achievement of women’s rights in the world. Solid proof of this was given by Ms. Samuel via her presentation.

Schoolchildren at the knowledge-sharing session.

The presenter did right by pointing to the seventies and eighties decades in Sri Lanka as being particularly notable from the viewpoint of women’s advocacy for justice. For those were decades when the country’s economy was unprecedentedly opened or liberalized, thus opening the floodgates to women’s increasing exploitation and disempowerment by the ‘captains of business’ in the Free Trade Zones and other locations where labour rights tend to be neglected.

Besides, those decades witnessed the explosive emergence of the North-East war and the JVP’s 1987-’89 uprising, for example, which led to power abuse by the state and atrocities by militant organizations, requiring women’s organizations to take up the cause of ethnic peace and connected questions, such as vast scale killings and disappearances.

However, the presenter was clear on the point that currently Sri Lanka is lagging behind badly on the matter of women’s empowerment. For example, women’s representation currently in local councils, provincial councils and parliament is appallingly negligible. In the case of parliament, in 2024 women’s representation was just 9.8 %. Besides, one in four local women have experienced sexual and physical violence since the age of fifteen. All such issues and more are proof of women’s enduring powerlessness.

Raaya Gomez, among other things, dealt at some length on how Sri Lanka is at present interacting with and responding to international bodies, such as CEDAW, that are charged with monitoring the country’s adherence to international conventions laying out the state’s obligations and duties towards women.

This year, we were told, the Sri Lankan government submitted 11 reports to CEDAW in Geneva on issues raised by the latter with the state. Prominent among these issues are continuing language-related difficulties faced by minority group Lankan women. Also coming to the fore is the matter of online harassment of women, now on the ascendant, and the growing need for state intervention to rectify these ills.

It was pointed out by the presenter that overall what needs to be fulfilled by Sri Lanka is the implementation of measures that contribute towards the substantive equality of women. In other words, social conditions that lead to the vulnerability and disempowerment of women need to be effectively managed.

Moreover, it was pointed out by Gomez that civil society in Sri Lanka comes by the opportunity to intervene for women’s empowerment very substantively when issues relating to the Lankan state’s obligations under CEDAW are taken up in Geneva, usually in February.

Accordingly, some Lankan civil society organizations were present at this year’s CEDAW sessions and they presented to the body 11 ‘shadow reports’ in response to those which were submitted by the state. In their documents these civil society groups highlighted outstanding issues relating to women and pointed out as to how the Lankan state could improve its track record on this score. All in all, civil society responses amount to putting the record straight to the international community on how successful or unsuccessful the state is in adhering to its commitments under CEDAW.

Thus, the BCIS forum helped considerably in throwing much needed light on the situation of Lankan women. Evidently, the state is yet to accelerate the women’s empowerment process. Governments of Sri Lanka and their wider publics should ideally come to the realization that empowered women are really an asset to the country; they contribute immeasurably towards national growth by availing of their rights and by adding to wealth creation as empowered, equal citizens.

Features

Richard de Zoysa at 67

by Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha

Today would have been Richard de Zoysa’s 67th birthday. That almost seems a contradiction in terms, for one could not, in those distant days of his exuberant youth, have thought of him as ever getting old. His death, when he was not quite 32, has fixed him forever, in the minds of those who knew and loved him, as exuding youthful energy.

It was 35 years ago that he was abducted and killed, and I fear his memory had begun to fade in the public mind. So we have to be thankful to Asoka Handagama and Swarna Mallawarachchi for bringing him to life again through the film about his mother. This was I think more because of Swarna, for I still recall her coming to see me way back in 2014 – August 28th it was, for my father was dying, though he was still mindful enough to ask me how my actress was after I had left him that afternoon to speak to her downstairs – to talk about her plans for a film about Manorani.

His friends have in general criticised the film, and I too wonder as to why she and the Director did not talk to more of his friends before they embarked on the enterprise. But perhaps recreating actual situations was not their purpose, or rather was not his, and that is understandable when one has a particular vision of one’s subject matter.

After listening to and reading the responses of his friends, I am not too keen to see the film, though I suspect I will do so at some stage. Certainly, I can understand the anger at what is seen as the portrayal of a drunkard, for this Manorani never to my knowledge was. But I think it’s absurd to claim there was never alcohol in the house, for there was, and Manorani did join in with us to have a drink, though she never drank to excess. Richard and I did, I fear, though not at his house, more at mine or at his regular haunt, the Art Centre Club.

I am sorry too that the ending of the film suggests that the murder was the responsibility of just its perpetrators, for there is no doubt that it was planned higher up. I myself have always thought it was Ranjan Wijeratne, who was primarily responsible, though I have no doubt that Premadasa also had been told – indeed Manorani told me that he had turned on Ranjan and asked why he had not been told who exactly Richard was.

But all that is hearsay, and it is not likely that we shall ever be able to find out exactly what happened. And otherwise it seems to me from what I have read, and in particular from one still I have seen (reproduced here), illustrating the bond between Richard and his mother, the film captures two vital factors, the extraordinary closeness of mother and son, and the overwhelming grief that Manorani felt over his death.

Despite this she fought for justice, and she also made it clear that she fought for justice not only for her son, but for all those whose loved ones had suffered in the reign of terror unleashed by JR’s government, which continued in Premadasa’s first fifteen months.

I have been surprised, when I was interviewed by journalists, in print and the electronic media, that none of them remembered Ananda Sunil, who had been taken away by policemen eight years earlier, when JR issued orders that his destructive referendum had to be won at all costs. Manorani told me she had met Ananda Sunil’s widow, who had complained, but had then gone silent, because it seemed the lives of her children had been threatened.

Manorani told me that she was comparatively lucky. She had seen her son’s body, which brought some closure, which the other women had not obtained. She had no other children, and she cared nothing for any threats against her own life for, as she said repeatedly, her life had lost its meaning with Zoysa’s death and she had no desire to live on.

I am thankful then that the film was made, and I hope it serves to renew Richard’s memory, and Manorani’s, and to draw attention to his extraordinary life, and hers both before and after his death. And I cannot be critical about the fact that so much about his life was left out, for a film about his mother’s response to his death could not go back to the past.

But it surprised me that the journalists did not know about his own past, his genius as an actor, his skill as a writer. All of them interviewed me for ages, for they were fascinated at what he had achieved in other spheres in his short life. Even though not much of this appeared in what they published or showed, I hope enough emerged for those interested in Richard to find out more about his life, and to read some of his poetry.

A few months after he died – I had been away and came back only six months later – I published a collection of his poetry, and then a few years later, having found more, republished them with two essays, one about our friendship, one about the political background to his death. And the last issue of the New Lankan Review, which he and I had begun together in 1983 in the tutory we had set up after we were both sacked from S. Thomas’, was dedicated to him. It included a striking poem by Jean Arasanayagam who captured movingly the contrast between his genius and the dull viciousness of his killers.

After those initial memorials to his life and his impact, I started working on a novel based on our friendship. I worked on this when I had a stint at the Rockefeller Centre in Bellagio in 1999, but I was not satisfied, and I worked on it for a few years more, before finally publishing the book in 2005. It was called The Limits of Love and formed the last book in my Terrorist Trilogy, the first book of which, Acts of Faith, had been written with his support, after the July 1983 riots. That was translated into Italian, as Atti di Fedi, and came out in 2006 in Milan.

The Limits of Love

did not receive much publicity, and soon afterwards I was asked to head the Peace Secretariat, and after that I wrote no more fiction. But when Godage & Bros had published several of my non-fiction works in the period after I was excluded from public life, I asked them to republish Acts of Faith, which they did, and that still remains in print. They also republished in 2020 Servants, my novel that won the Gratiaen Prize for 1995.

I thought then that it would be a good idea to republish The Limits of Love, and was delighted that Neptune agreed to do this, after the success of my latest political history, Ranil Wickremesinghe and the emasculation of the United National Party. I thought initially of bringing the book out on the anniversary of Richard’s death, but I had lost my soft copy and reproducing the text took some time. And today being Poya I could not launch the book on his birthday.

It will be launched on March 31st, when Channa Daswatte will be free to speak, for I recalled that 20 years ago my aunt Ena told me that he had admired the book. I think he understood it, which may not have been the case with some of Richard’s friends and relations, for this too is fiction, and the Richard’s character shares traits of others, including myself. The narrator, the Rajiv’s character, I should add is not myself, though there are similarities. He is developed from a character who appeared in both Acts of Faith and Days of Despair, though under another name in those books. Rajiv in the latter is an Indian Prime Minister, though that novel, written after the Indo-Lanka Accord, is too emotional to be easily read.

Manorani hardly figures in The Limits of Love. A Ranjan Wijesinghe does, and also a Ronnie Gooneratne, but of more interest doubtless will be Ranil and Anil, two rival Ministers under President Dicky, both of whom die towards the end of the book. Neither, I should add, bears the slightest resemblance to Ranil Wickremesinghe. His acolytes may try to trace elements of him in one or other of the characters, for I remember being told that Lalith Athulathmudali’s reaction to Acts of Faith was indignation that he had not appeared in it.

Fiction has, I hope, the capacity to bring history to life, and the book should be read as fiction. Doubtless there will be criticism of the characterisation, and of course efforts to relate this to real people, but I hope this will not detract from the spirit of the story, and the depiction of the subtlety of political motives as well as relationships.

The novel is intended to heighten understanding of a strange period in our history, when society was much less fragmented than it is today, when links between people were based on blood as much as on shared interests. But I hope that in addition it will raise awareness of the character of the ebullient hero who was abducted and killed 35 years ago.

The film has roused interest in his life, though through a focus on his death. The novel will I hope heighten awareness of his brilliance and the range of his activity in all too short a life.

Features

SL Navy helping save kidneys

By Admiral Ravindra C Wijegunaratne

WV, RWP& Bar, RSP, VSV, USP,

NI (M) (Pakistan), ndc, psn, Bsc (Hons) (War Studies) (Karachi) MPhil (Madras)

Former Navy Commander and Former Chief of Defense Staff

Former Chairman, Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd

Former Managing Director Ceylon Petroleum Corporation

Former High Commissioner to Pakistan

Navy’s efforts to eradicate Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) from North Central and North Western Provinces:

• Navy’s homegrown technology provides more than Ten million litres of clean drinking / cooking water to the public free of charge.

• Small project Navy started on 22nd December 2015 providing great results today.

• 1086 Reverse Osmosis (RO) Water purification plants installed to date – each plant producing 10,000 litres of clean drinking water – better quantity than bottled water.

• Project continued for 10 years under seven Navy Commanders highlights the importance of “INSTITUTIONALIZING” a worthy project.

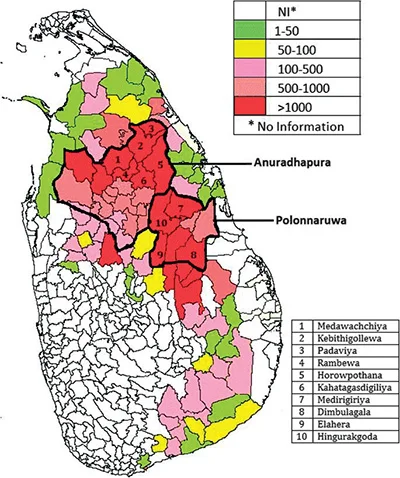

What you see on the map of Sri Lanka (Map 1) are RO water purification plants installed by SLN.SLN is famous for its improvisations and innovations in fighting LTTE terrorists out at sea. The Research and Development Institute of SLN started to use its knowledge and expertise for “Nation Building” when conflict was over in May 2009. On request of the Navy Commander, R and D unit of SLN, under able command of Commander (then) MCP Dissanayake, an Indian trained Marine Engineer, embarked on a programme to build a low- cost RO plant.

What you see on the map of Sri Lanka (Map 1) are RO water purification plants installed by SLN.SLN is famous for its improvisations and innovations in fighting LTTE terrorists out at sea. The Research and Development Institute of SLN started to use its knowledge and expertise for “Nation Building” when conflict was over in May 2009. On request of the Navy Commander, R and D unit of SLN, under able command of Commander (then) MCP Dissanayake, an Indian trained Marine Engineer, embarked on a programme to build a low- cost RO plant.

The Chronic Kidney Disease was spreading in North Central Province like a “wildfire “in 2015, mainly due to consumption of contaminated water. To curb the situation, providing clean drinking and cooking water to the public was the need of the hour.

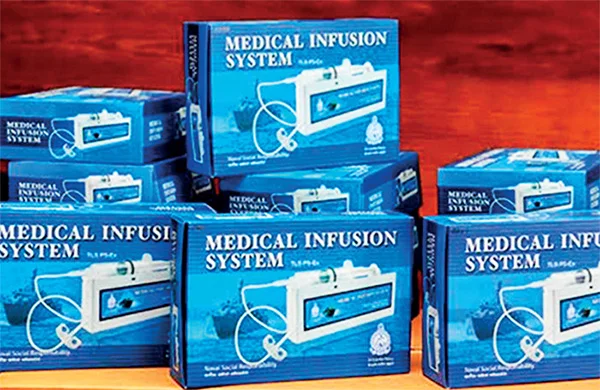

The Navy had a non-public fund known as “Naval Social Responsibility Fund “(NSR) started by former Navy Commander Admiral DWAS Dissanayake in 2010, to which all officers and sailors contributed thirty rupees (Rs 30) each month. This money was used to manufacture another project- manufacturing medicine infusion pumps for Thalassemia patients. Thalassemia Medicine Infusion pumps manufactured by SLN R and D Unit. With an appropriately 50,000 strong Navy, this fund used to gain approximately Rupees 1.5 million each month- sufficient funds to start RO water purification plant project.

Studies on the spreading of CKD, it was very clear of danger to the people of North central and North Western provinces, especially among farmers, in this rice producing province. The detailed studies on this deadly disease by a team led by Medical experts produced the above map (see Map 2) indicating clear and present danger. Humble farmers in “the Rice Bowl” of Sri Lanka become victims of CDK and suffer for years with frequent Dialysis Treatments at hospitals and becoming very weak and unable to work in their fields.

- Map 1

- Map 2

The Navy took ten years to complete the project, under seven Navy Commanders, namely Admiral Ravi Wijegunaratne, Admiral Travis Sinniah, Admiral Sirimevan Ranasinghe, Admiral Piyal De Silva, Admiral Nishantha Ulugethenna, Admiral Priyantha Perera, present Navy Commander Kanchana Banagoda. Total cost of the project was approximately Rs. 1.260 million. Main contributors to the project were the Presidential Task Force to Eradicate CDK (under the then President Mithripala Sirisena), Naval Social Responsibility Fund, MTV Gammedda, individual local and foreign donors and various organisations. Their contributions are for a very worthy cause to save the lives of innocent people.

The Navy’s untiring effort showed the World what they are capable of. The Navy is a silent force. What they do out at sea has seen only a few. This great effort by the Navy was also noticed by few but appreciated by humble people who are benefited every day to be away from deadly CKD. The Reverse Osmosis process required power. Each plant consumes approximately Rs 11,500 worth power from the main grid monthly. This amount brought down to an affordable Rs 250 per month electricity bill by fixing solar panels to RO plant building roofs. Another project to fix medical RO plants to hospitals having Dialysis machines. SLN produced fifty medical RO plants and distributed them among hospitals with Dialysis Machines. Cost for each unit was Rs 1.5 million, where an imported plant would have cost 13 million rupees each. Commodore (E) MCP Dissanayake won the prize for the best research paper in KDU international Research Conference 2021 for his research paper to enhance RO plant recovery from 50% to 75%. He will start this modification to RO plants soon making them more efficient. Clean drinking water is precious for mankind.

Thalassemia Medicine Infusion pumps manufactured by SLN R and D Unit

The Navy has realised it very well. In our history, King Dutugemunu (regained from 161 BC to 137 BC), united the country after 40 years and developed agriculture and Buddhism. But King Dutugemunu was never considered a god or deified. However, King Mahasen (277 to 304 AD) who built more than 16 major tanks was considered a god after building the Minneriya tank.

The people of the North Central Province are grateful to the Navy for providing them with clean drinking and cooking water free of charge daily. That gratitude is for saving them and their children from deadly CKD.

Well done Our Navy! Bravo Zulu!

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoPrivate tuition, etc., for O/L students suspended until the end of exam

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoShyam Selvadurai and his exploration of Yasodhara’s story

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoRanil roasted in London

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoS. Thomas’ beat Royal by five wickets in the 146th Battle of the Blues

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoTeachers’ union calls for action against late-night WhatsApp homework

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoHeroes and villains

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe JVP insurrection of 1971 as I saw it as GA Ampara

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoPolice looking for their own head