Opinion

The Life and Lessons of Sir Waitialingam Duraiswamy

By Arjuna Parakrama

Text of an introductory speech delivered recently in Colombo by Prof. Arjuna Prarakrama on the occasion of the launching of the publication titled, ‘Clippings on the Life and Times of Sir Waitialingam Duraisawamy’ by Sivanandini Duraiswamy.

I shall confine my brief remarks to four areas in all of which, I believe Sir Waitialingam had in his inimitable, quiet but firm, steadfast, way shown us a path and a perspective that today, more than ever before, is worth understanding and attempting to follow. I shall try to use his religio-cultural tradition, not mine, to explain his ways and values, in part because that would provide the greatest explanatory power, and because for too long we have remained trapped, both wittingly and unwittingly in our own cultural and religious traditions, which then serve to divide and exclude. If we are to be serious about integration we have no right to the luxury owning only one of many threads in our national mosaic.

To this end, let me begin with an overall assessment of Sir Waitialingam as I believe and see captured in the extraordinary poem found in the Puraananuru (182) by Ilam Peruvaiyuti in the extraordinary translation by A.K. Ramanujan. This is a beautiful summary of the kind of man I believe Sir Waitialingam was, as well as of the kind role men like him play in society.

The World Lives Because

This world lives

because

some men

do not eat alone,

not even when they get

the sweet ambrosia of the gods;

they’ve no anger in them,

they fear evils other men fear

but never sleep over them;

give their lives for honor,

will not touch a gift of whole worlds

if tainted;

there’s no faintness in their hearts

and they do not strive

for themselves.

Because such men are,

This world is.

This is both the potential and catastrophe of our times. The Sangam poetry of over 2000 years ago can be excused for focusing only on men, but certainly not us in Sri Lanka today. We have no women or men of this kind here anymore, at least in positions of authority and power, so our world is in danger of disintegrating – of not being “is” any longer. It “was” but it “isn’t” now, and alas, we must all share some blame for this. My humble intervention today, is, then, a celebration of Sir Waitialingam’s life and values, as well as the performance of obsequies for a lost time, a bereft space, trapped in the past.

This should not be: systems need to be in place, institutions need to function, which go beyond individuals. For the author of the Thirukural (verse 982), the matter was strikingly simpler:

The welfare of the world is in the goodness of those who govern.

It depends on the nature that resides within.

We must believe otherwise, but yet, without visionary leaders of the kind of Sir Waitialingam, we are doomed to echo Antonio Gramsci, referring to a different kind of fascism, of which I shall use the liberal translation of Gramsci popularised by Slavoj Žižek (2010).

“The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.”

Systems have failed us, as have leaders, and echoing Shakespeare’ Prospero, we must take responsibility for “this thing of darkness / which [we] acknowledge [ours].”

Beginning with a Kural that sums up greatness in our sense, I will attempt to take stock of the lessons we can learn from the life of Sir Waitialingam on the occasion of the launch of Clippings.

Love, modesty, beneficence, benignant grace,

With truth, are pillars five of perfect virtue’s resting-place. [The Virtuous: Verse 983]

Thus, the core values that I would like to focus on today as lessons and examples include integrity, giving, impartiality, and simplicity.

INTEGRITY

The question of integrity, fundamental in its absence, in its utter dereliction. today, is embodied in Sir Waitialingam’s philosophy and practice of life. As Sir Francis Molamure wrote in 1936:

“Mr. Duraiswamy proved his sterling worth and political integrity during the term of the Reformed Council of 1924. There is no doubt that he is the outstanding political figure among the Tamils.”

A.F. Molamure, Times of Ceylon Feb 1936 [p. 101]

Dr. N.M Perera in his Vote of Condolence reproduced in the Hansard of 1966 has this to say:

“He was a man of whom we can be proud, and the Legislature can be proud, and certainly we in this country can be proud. He had a sense of fair play, justice and a high sense of integrity and, above all, he was a genial person who always discussed matters frankly with all Members in the Speaker’s Chamber, listened to their difficulties and pointed out ways of solving their difficulties. In essence, he was an ideal Speaker. All of us looked up to him to maintain the high honour and dignity that was expected of the Chair.

We have lost … one of the old politicians of this country. He was one of the last links between the old and the new.”

Hansard of 1966: Dr. N. M. Perera [Vote of Condolence]

The point to be made here is that integrity is not a matter of avoidance, integrity is not a matter of turning the other side and becoming consciously unaware of what is going on. Integrity is an engagement, it is, as Dr. Perera says, frank engagement on key matters, listening to difficulties, solving problems. Sir Waitialingam was someone who confronted injustice, inequality and wrongs and actively helped to right these wrongs. Integrity is not passive, it is not the absence of corruption, nepotism, kleptocracy nor the avoidance of personal gain: it is the active campaigning and active engagement against those cancers that affect integrity, be they people or institutions, ideologies or fiefdoms, whether they seek refuge in culture and tradition, or hierarchy and protocol. But, this integrity must be lived and practiced: it is not merely a slogan for the hard times in opposition backbenches, for garnering votes at elections. In this sense, the integrity embodied by Sir Waitialingam was tied to his dignity and moral compass as surely as his religion and family values.

The Thirukural, in verse 119 expresses this quite poignantly:

Speech uttered without bias is integrity,

Provided no unspoken bias hides in the heart.

This is the crux of the problem which goes beyond avoidance, subterfuge hypocrisy and so on. I will have occasion to talk about heart of greatness later on, but let me move on now.

GIVING

Next, I would like to focus on the notion of giving, which is not charity, but which is an understanding of equality, a redressing of injustice, a restoration of the level playing field. And, I must say that again I have to rely on a translation of the Tirukkuṟaḷ, verse 218, which I think is important, because one does not have to be hugely financially rich to have that sense of giving. In fact, it is a sad truism to say those who are hugely financially rich do not indulge in such giving today, but in taking more and more.

Here is the Kural:

Those who deeply know duty do not neglect giving,

Even in their own unprosperous season.

In his quiet retirement he was as prone to giving as he was earlier. And in fact, his role as the Speaker – even though he was scrupulous to the point of not being involved officially in either parties or politics – provides a shining counter-example to the current dispensation. Here, he was able through his good offices, his persuasive powers and the force of his character to enable the people in the islands, particularly in Delft, to obtain services that were unthought of earlier. Motorised boats, piers and so on.

But, most importantly, it was not done irregularly, it was not done unfairly, it was not done in order to canvas or bargain or buy votes; it was done because it was a duty, a duty seen as a labor of love and, crucially, it was something for which he never took credit. These I think are unique examples to our present and future generations.

Again, from the Thirukural (211)

The benevolent expect no return for their dutiful giving.

How can the world ever repay the rain cloud?

Sir Waitialingam was a rain cloud to the islands, to the Jaffna peninsula, to the people who came to him or of whom he recognized a hope, and this was remarkable because it was not part of a quid pro quo, it was not a political circus. It was quiet, it was discreet, and it addressed the need of the hour.

“I feel so helpless, so small, so unable to do what is expected of me. In my home I feel

strongly about the great wants of our people and often felt and wept that something should be done to raise our people’s standard of living, education and physical conditions. This frail body is unable to cope with the stupendous work that lies before me.” [p. 146]

IMPARTIALITY

Perhaps the most difficult principle to engage because he and I like many are ambiguous about its benefits or to be precise the greater benefit was Sir Waitialingam’s impartiality. The moment he became the Speaker of the State Council, he ceased to be the uncontested MP for Kayts, he ceased to be the representative of the Tamil people, he ceased to be a son of the soil. He identified himself, and he became, one with all the interests of all the people in the country.

D.B Dhanapala puts this quite beautifully and quite accurately in his description of the early stages of Sir Waitialingam’s tenure, when he states:

It is a lie to say the Speaker takes no sides. As a matter of fact, he takes sides more than any man on the floor of the House. But he takes all the sides available on any question at different times.

He seems as much concerned and interested in the halting sentences of the most insignificant backbencher as desperate defence put up by the leader of the House.

The smile of interest is thin; the nod of understanding is slight. But there is nothing mechanical about these encouragements on the part of the Speaker, His behaviour when on the chair seems to be always in evening dress, as it were. There is a formal dignity not without grace that clothes the few words he sometimes utters, the smile he often proffers and even the raising of the eye-brows he but seldom affects.

I think it is worth understanding that impartiality taken to the extreme in order to reconcile his understanding of the principle role and function of the Speaker, may be a disadvantage or even a tragedy of our times.

Mr Duraiswamy does not speak too much. And whenever he does speak, he says the right thing. There is also a complete lack of what is called ‘side’ in his behaviour which makes his personality unobtrusive in the House. His rulings are often firm. …

But his firmness is not off his own bat. He takes the sense of the House when he is in doubt. At other times he seems to scent the feeling prevalent. But in whatever he does there is the touch of the sure hand, the ring of the decided mind about it.” [pp. 42- 43]

Unfortunately, when Ceylon obtained the services of the most important Speaker and the first citizen in Sir Waitialingam Duraiswamy, we also lost a powerful advocate, a strong voice for united Ceylon whose liberalism found him putting aside less important ethnic, cultural differences at that crucial juncture, and this loss I think proved fundamental in the history that unfolded at the time. The trade-off was identified by many as the quid pro quo for his being elected and in his demonstrating so exemplary a level of impartiality for 11 crucial years in that office.

However one wishes to rationalize it, Sir Waitialingam’s eloquence in the House, his ability to reason and explain using his judicial training, his ability to analyze and understand an issue were sadly missed. And unfortunately, he too was well aware of this. Mr. Dhanapala observes:

At my last interview with him, on the eve of his departure to England, I found him greatly perturbed regarding the trend of events. He felt all the worse because as Speaker he was helpless.

With the highest conceptions of the duties of the Office he holds, the Speaker would not take part in politics even behind the scenes. But a Speaker has his own opinions unexpressed in public. [pp. 46-47]

The issue there was he was unhappy because of the communal turn of politics at that time. He was unhappy and prescient about what would happen in future, and it did. It led him to exclude himself from politics and public life after 1947. Being scrupulous and a stickler for due process, he eschewed working in the unofficial Bar as well, proving all those wrong, including Dhanapala, who felt that his political career would continue to blossom. However, exclusionary nationalist politics had overtaken the country, inevitably, and from the point of view of non-Sinhala groups, justifiably, but this was not a political arena that Sir Waitialingam trusted or valued, and in turn it was not one in which his worth was duly recognised.

Dr N.M. Perera states in 1966: how wrong he was proven to be:

It used to be a common theme of discussion between himself and myself as to how best the problem of communal tension that seemed to prevail in the last decade or so could be solved. I always maintained – and I think he agreed – that this was a passing phase.

I don’t think that he was right even about Sir Waitialingam’s view: my evidence, beyond the circumstantial, is that despite referring to this as “a common theme of discussion” he is as yet unsure of Sir Waitialingam’s view on the subject of such frequent discussion. Perhaps politeness intervened here!

REFINED SIMPLICITY

In an extraordinarily felicitous phrase, DB Dhanapala captures what I consider to be the essence of Sir Waitialingam’s personal uniqueness vis-à-vis the other politicians of his time. All of them were elite, educated sufficiently and comfortably westernised. Yet, Sir Waitialingam had that quality of refined simplicity which he bore with the aplomb and flair.

In the words of Dhanapala,

“In their dealings with their own countrymen, the best class of Sinhalese has copied the superior manner in which the European in the east treats the Asiatic. They are seldom able to get away from that sahib brusqueness, and not many single use politicians will ever attain that refined simplicity of the high class Dravidian as personified in Mr. Duraiswamy. . . . Here is a man without all the complexities of pose and pomp — who talks to his inferiors with the same respect as he would to equals. This wiry athletic Dravidian in a long coat, who sleeps on a hard plank to this day, is prouder of his fame as a farmer then of his name as a politician or lawyer.”

The point I wish to make is that when Sir Waitilingam speaks of a united Ceylon and its shared heritage, he’s not like some others of his time speaking about Oxford or Cambridge, Victorian values, a Christian ethos or even the unabashedly upper class Colombo milieu of like-minded Sinhala, Tamil, Muslim and Burgher fraternities conjoined by the old school tie, More British than the British themselves, as Macaulay planned a century earlier in his infamous Minute on Indian Education (Not accidentally the year that Royal College – then The Colombo Academy – was founded): “We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern, -a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.”

This simplicity is neither contrived nor natural. Paradoxically it is a learned and deliberately chosen simplicity based on values and beliefs. The frills of office, of colonialist public life were not beyond Sir Waitialingam’s enjoyment. He could take it or leave it. He was most comfortable in Jaffna in his home with his family and friends in communion with his guru among his people. The example most illustrative of this point is his rapid departure from Colombo to Jaffna on returning after being knighted so that he can be with his family and well-wishers. His remark on that occasion is symptomatic of that refined simplicity the eschewing of pomp and pageantry in favour of deeply rooted, understated yet firmly held beliefs and practices.

“I could not resist the strong urge to be in Jaffna a minute longer and I am here now among you,” he said by way of explaining to his friends the reason for his hurried departure from Colombo soon after his return from England.” [p. 139]

Conclusion

Destiny’s last days may surge with oceanic change,

Yet men deemed perfectly good remain, like the shore, unchanged.

Verse 989

It has been noted of this milieu that “this is a small world.” We now need to confront the inescapable fact that this is not so any longer. There’s both good and bad in this new reality, notwithstanding its monsters. A larger world allows for greater participation, widespread upward social mobility and the drastic reduction of old class-caste hierarchies that dominated this small world in the past. Yet, while saluting and championing this sea change, we must find room for all that was the best of that past. Sir Waitialingam was certainly, irrefutably among the exemplars we must learn to cherish, unlearn our own present madness to understand, value and emulate.

His life remains an antidote to the brutes of our epoch, beautifully captured in this new translation by Dr. S. V. Kasynathan, of Kural 1020, one of the most poignant reminders of our current predicament.

The movement of men without shame within their heart

Is like wooden puppets on a string pretending to be alive. [Kural 1020]

After such knowledge, what forgiveness?

Opinion

Capt. Dinham Suhood flies West

A few days ago, we heard the sad news of the passing on of Capt. Dinham Suhood. Born in 1929, he was the last surviving Air Ceylon Captain from the ‘old guard’.

He studied at St Joseph’s College, Colombo 10. He had his flying training in 1949 in Sydney, Australia and then joined Air Ceylon in late 1957. There he flew the DC3 (Dakota), HS748 (Avro), Nord 262 and the HS 121 (Trident).

I remember how he lent his large collection of ‘Airfix’ plastic aircraft models built to scale at S. Thomas’ College, exhibitions. That really inspired us schoolboys.

In 1971 he flew for a Singaporean Millionaire, a BAC One-Eleven and then later joined Air Siam where he flew Boeing B707 and the B747 before retiring and migrating to Australia in 1975.

Some of my captains had flown with him as First Officers. He was reputed to have been a true professional and always helpful to his colleagues.

He was an accomplished pianist and good dancer.

He passed on a few days short of his 97th birthday, after a brief illness.

May his soul rest in peace!

To fly west my friend is a test we must all take for a final check

Capt. Gihan A Fernando

RCyAF/ SLAF, Air Ceylon, Air Lanka, Singapore Airlines, SriLankan Airlines

Opinion

Global warming here to stay

The cause of global warming, they claim, is due to ever increasing levels of CO2. This is a by-product of burning fossil fuels like oil and gas, and of course coal. Environmentalists and other ‘green’ activists are worried about rising world atmospheric levels of CO2. Now they want to stop the whole world from burning fossil fuels, especially people who use cars powered by petrol and diesel oil, because burning petrol and oil are a major source of CO2 pollution. They are bringing forward the fateful day when oil and gas are scarce and can no longer be found and we have no choice but to travel by electricity-driven cars – or go by foot. They say we must save energy now, by walking and save the planet’s atmosphere.

THE DEMON COAL

But it is coal, above all, that is hated most by the ‘green’ lobby. It is coal that is first on their list for targeting above all the other fossil fuels. The eminently logical reason is that coal is the dirtiest polluter of all. In addition to adding CO2 to the atmosphere, it pollutes the air we breathe with fine particles of ash and poisonous chemicals which also make us ill. And some claim that coal-fired power stations produce more harmful radiation than an atomic reactor.

STOP THE COAL!

Halting the use of coal for generating electricity is a priority for them. It is an action high on the Green party list.

However, no-one talks of what we can use to fill the energy gap left by coal. Some experts publicly claim that unfortunately, energy from wind or solar panels, will not be enough and cannot satisfy our demand for instant power at all times of the day or night at a reasonable price.

THE ALTERNATIVES

It seems to be a taboo to talk about energy from nuclear power, but this is misguided. Going nuclear offers tried and tested alternatives to coal. The West has got generating energy from uranium down to a fine art, but it does involve some potentially dangerous problems, which are overcome by powerful engineering designs which then must be operated safely. But an additional factor when using URANIUM is that it produces long term radioactive waste. Relocating and storage of this waste is expensive and is a big problem.

Russia in November 2020, very kindly offered to help us with this continuous generating problem by offering standard Uranium modules for generating power. They offered to handle all aspects of the fuel cycle and its disposal. In hindsight this would have been an unbelievable bargain. It can be assumed that we could have also used Russian expertise in solving the power distribution flows throughout the grid.

THORIUM

But thankfully we are blessed with a second nuclear choice – that of the mildly radioactive THORIUM, a much cheaper and safer solution to our energy needs.

News last month (January 2026) told us of how China has built a container ship that can run on Thorium for ten years without refuelling. They must have solved the corrosion problem of the main fluoride mixing container walls. China has rare earths and can use AI computers to solve their metallurgical problems – fast!

Nevertheless, Russia can equally offer Sri Lanka Thorium- powered generating stations. Here the benefits are even more obviously evident. Thorium can be a quite cheap source of energy using locally mined material plus, so importantly, the radioactive waste remains dangerous for only a few hundred years, unlike uranium waste.

Because they are relatively small, only the size of a semi-detached house, such thorium generating stations can be located near the point of use, reducing the need for UNSIGHTLY towers and power grid distribution lines.

The design and supply of standard Thorium reactor machines may be more expensive but can be obtained from Russia itself, or China – our friends in our time of need.

Priyantha Hettige

Opinion

Will computers ever be intelligent?

The Island has recently published various articles on AI, and they are thought-provoking. This article is based on a paper I presented at a London University seminar, 22 years ago.

Will computers ever be intelligent? This question is controversial and crucial and, above all, difficult to answer. As a scientist and student of philosophy, how am I going to answer this question is a problem. In my opinion this cannot be purely a philosophical question. It involves science, especially the new branch of science called “The Artificial Intelligence”. I shall endeavour to answer this question cautiously.

Philosophers do not collect empirical evidence unlike scientists. They only use their own minds and try to figure out the way the world is. Empirical scientists collect data, repeat and predict the behaviour of matter and analyse them.

We can see that the question—”Will computers ever be intelligent?”—comes under the branch of philosophy known as Philosophy of Mind. Although philosophy of mind is a broad area, I am concentrating here mainly on the question of consciousness. Without consciousness there is no intelligence. While they often coincide in humans and animals, they can exist independently, especially in AI, which can be highly intelligent without being conscious.

AI and philosophers

It appears that Artificial Intelligence holds a special attraction for philosophers. I am not surprised about this as Al involves using computers to solve problems that seem to require human reasoning. Apart from solving complicated mathematical problems it can understand natural language. Computers do not “understand” human language in the human sense of comprehension; rather, they use Natural Language Processing (NLP) and machine learning to analyse patterns in data. Artificial Intelligence experts claim certain programmes can have the possibility of not only thinking like humans but also understanding concepts and becoming conscious.

The study of the possible intelligence of logical machines makes a wonderful test case for the debate between mind and brain. This debate has been going on for the last two and a half centuries. If material things, made up entirely of logical processes, can do exactly what the brain can, the question is whether the mind is material or immaterial.

Although the common belief is that philosophers think for the sake of thinking, it is not necessarily so. Early part of the 20th century brought about advances in logic and analytical philosophy in Britain. It was a philosopher (Ludwig Wittgenstein) who invented the truth table. This was a simple analytic tool useful in his early work. But this was absolutely essential to the conceptual basis of early computer science. Computer science and brain science have developed together and that is why the challenge of the thinking machine is so important for the philosophy of mind. My argument so far has been to justify how and why AI is important to philosophers and vice versa.

Looking at computers now, we can see that the more sophisticated the computer, the more it is able to emulate rather than stimulate our thought processes. Every time the neuroscientists discover the workings of the brain, they try to mimic brain activity with machines.

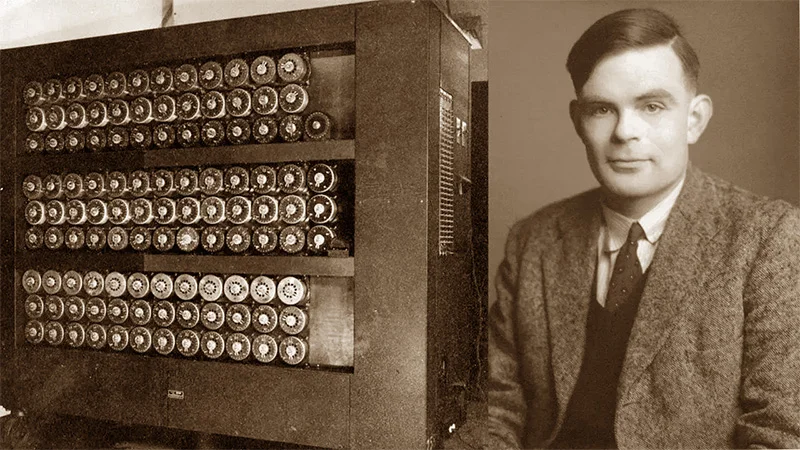

How can one tell if a computer is intelligent? We can ask it some questions or set a test and study its response and satisfy ourselves that there is some form of intelligence inside this box. Let us look at the famous Alan Turing Test. Imagine a person sitting at a terminal (A) typing questions. This terminal is connected to two other machines, (B) and (C). At terminal (B) sits another person (B) typing responses to the questions from person (A). (C) is not a human being, but a computer programmed to respond to the questions. If person (A) cannot tell the difference between person (B) and computer(C), then we can deduce that computer is as intelligent as person (B). Critics of this test think that there is nothing brilliant about it. As this is a pragmatic exercise and one need not have to define intelligence here. This must have amused the scientists and the philosophers in the early days of the computers. Nowadays, computers can do much more sophisticated work.

Chinese Room experiment

The other famous experiment is John Sealer’s Chinese room experiment. *He uses this experiment to debunk the idea that computers could be intelligent. For Searle, the mind and the brain are the same. But he warns us that we should not get carried away with the emulative success of the machines as mind contains an irreducible subjective quality. He claims that consciousness is a biological process. It is found in humans as well as in certain animals. It is interesting to note that he believes that the mind is entirely contained in the brain. And the empirical discovery of neural processes cannot be applied to outside the brain. He discards mind-body dualism and thinks that we cannot build a brain outside the body. More commonly, we believe the mind is totally in the brain, and all firing together and between, and what we call ‘thought’ comes from their multifarious collaboration.

Patricia and Paul Churchland are keen on neuroscientific methods rather than conventional psychology. They argue that the brain is really a processing machine in action. It is an amazing organ with a delicately organic structure. It is an example of a computer from the future and that at present we can only dream of approaching its processing speed. I think this is not something to be surprised about. The speed of the computer doubles every year and a half and in the distant future there will be machines computing faster than human beings. Further, the Churchlands’, strongly believe that through science one day we will replicate the human brain. To argue against this, I am putting forward the following true story.

I remember watching an Open University (London) education programme some years ago. A team of professors did an experiment on pavement hawkers in Bogota, Colombia. They were fruit sellers. The team bought a large number of miscellaneous items from these street vendors. This was repeated on a number of occasions. Within a few seconds, these vendors did mental calculations and came out with the amounts to be paid and the change was handed over equally fast. It was a success and repeatable and predictable. The team then took the sample population into a classroom situation and taught them basic arithmetic skills. After a few months of training they were given simple sums to do on selling fruit. Every one of them failed. These people had the brain structure that of ordinary human beings. They were skilled at their own jobs. But they could not be programmed to learn a set of rules. This poses the question whether we can create a perfect machine that will learn all the human transferable skills.

Computers and human brains excel at different tasks. For instance, a computer can remember things for an infinite amount of time. This is true as long as we don’t delete the computer files. Also, solving equations can be done in milliseconds. In my own experience when I was an undergraduate, I solved partial differential equations and it took me hours and a lot of paper. The present-day students have marvellous computer programmes for this. Let alone a mere student of mathematics, even a mathematical genius couldn’t rival computers in the above tasks. When it comes to languages, we can utter sentences of a completely foreign language after hearing it for the first time. Accents and slang can be decoded in our minds. Such algorithms, which we take for granted, will be very difficult for a computer.

I always maintain that there is more to intelligence than just being brilliant at quick thinking. A balanced human being to my mind is an intelligent person. An eccentric professor of Quantum Mechanics without feelings for life or people, cannot be considered an intelligent person. To people who may disagree with me, I shall give the benefit of the doubt and say most of the peoples’ intelligence is departmentalised. Intelligence is a total process.

Other limitations to AI

There are other limitations to artificial intelligence. The problems that existing computer programmes can handle are well-defined. There is a clear-cut way to decide whether a proposed solution is indeed the right one. In an algebraic equation, for example, the computer can check whether the variables and constants balance on both sides. But in contrast, many of the problems people face are ill-defined. As of yet, computer programmes do not define their own problems. It is not clear that computers will ever be able to do so in the way people do. Another crucial difference between humans and computers concerns “common sense”. An understanding of what is relevant and what is not. We possess it and computers don’t. The enormous amount of knowledge and experience about the world and its relevance to various problems computers are unlikely to have.

In this essay, I have attempted to discuss the merits and limitations of artificial intelligence, and by extension, computers. The evolution of the human brain has occurred over millennia, and creating a machine that truly matches human intelligence and is balanced in terms of emotions may be impossible or could take centuries

*The Chinese Room experiment, proposed by philosopher John Searle, challenges the idea that computers can truly “understand” language. Imagine a person locked in a room who does not know Chinese. They receive Chinese symbols through a slot and use an instruction manual to match them with other symbols to produce correct replies. To outsiders, it appears the person understands Chinese, but in reality, they are only following rules. Searle argues that similarly, a computer may process language convincingly without genuine understanding or consciousness.

by Sampath Anson Fernando

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Midweek Review2 days ago

Midweek Review2 days agoA question of national pride