Features

Saving Sinharaja: A rainforest under threat

(Excerpted from the authorized biography of Thilo Hoffmann by Douglas. B. Ranasinghe)

Sinharaja is the last undisturbed extent of rainforest in Sri Lanka. It lies across the boundary between the Sabaragamuwa and Southern Provinces, within the Ratnapura, Galle and Matara Districts.

The protected area officially named Sinharaja, so situated, is part of a larger forest of that name. The rest of it includes Forest Reserves or Proposed Reserves under other names, some of which are mentioned below. In their midst lay the Sinharaja Forest Reserve and the Sinharaja Proposed Forest Reserve, a continuous area of forest divided thus for formal reasons.

In the late 1960s politicians, administrators and even the public were unaware of the unique value of rainforests. The State began to intensify the exploitation of wet-zone forests to meet the growing demand for timber, especially plywood. Questions relating to the environment, the conservation of unique systems of biodiversity, gene pools, and the other natural riches such forests yield were not asked.

The State Timber Corporation, contracted by the Forest Department under its Forestry Master Plan, commenced log extraction in the wider Sinharaja area from the Morapitiya-Runakanda forest.A plywood and chipboard complex with a processing capacity of four million cubic feet per year was built with Romanian aid at Kosgama. This was 85 km northwest of Sinharaja.

It was decided that the wood to feed it would be taken from Sinharaja, mainly the two Sinharaja Reserves, and that for this purpose the entire extent of pristine rainforest they held was to be selectively logged. Aid was obtained from Canada for this project to be carried out by mechanized means on a massive scale.

Outside the forest the Canadian contractors built and widened roads, strengthened bridges and culverts, and set up a large timber yard at the Dela railway station (the KV line’ then extended to this area and beyond), from where the timber would be freighted to the Kosgama factory. They cleared and built from Veddagala to Sinharaja a wide road sufficient for their equipment to be hauled in and for huge lorries to transport the timber out.

Into Sinharaja they moved the heaviest logging and extraction machinery then known. Where the Research Station stands today there rose a machine yard and repair shop, the ground soaked with engine fuel and lubricants.

The need to rescue a forest

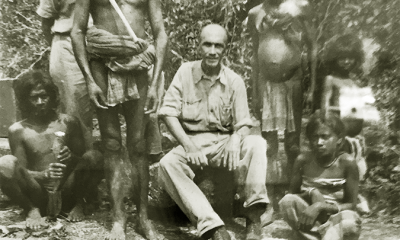

At the time that the State turned to it in the quest for material self-sufficiency, Sinharaja was regarded as remote and mysterious, and had hardly ever been visited by a biologist, or even explored.In 1969 at the Annual General Meeting of the WNPS its President, Thilo Hoffmann, made special mention of the threat to this unexplored but invaluable asset of the country.

The following year a deputation from the General Committee of the Society led by him met the Chairmen d the State Timber and Plywood Corporations. Through them they persuaded the Forest Department to spare 1,000 to 1,200 acres of Sinharaja as a scientific reserve.

Delegations from the WNPS continued to bring the matter up at meetings with relevant Government committees and agencies. With Thilo they met the Conservator of Forests, too, for this purpose.

At the AGM for 1971 in December that year, member Vere de Mel moved the following resolution; and he in particular urged repeatedly that the Society should take further action.

“That this Society requests its Committee, if after a full study it considers it desirable to do so, to use every possible means to check the denudation of the Sinharaja Forest Reserve for the purpose of exploiting its timber for a Government Plywood Factory.”

It was up to Thilo, to initiate the action. He decided to visit the forest. Sam Elapata Jr., a long-standing committee member of the WNPS, and a close friend of his, lived at Nivitigala near Sinharaja. In an article on Thilo in the 50th anniversary issue of Loris (1986), he recounts that Thilo came to his house, and what he said, thus:

“Sam, let’s go and see the Sinharaja in its pristine glory before the people ravage and exploit it. I would like your children also to see it, because it is their heritage. Maybe one of them will remember it as it was and what has happened to it, and we may still make a conservationist out of him.” He was already thinking of the future.

Thilo spent three days, February 26-28, 1972, on extensive trips into the Sinharaja Reserves and the surrounding areas, partly with Sam, his small son Upali and Chandra Liyanage. He observed and noted the status of the forest, its fauna and flora, the people and their economy.

What he saw convinced him that the Society had to do all in its power to persuade the Government that the intact forest was worth far more than the timber, and that the Sinharaja logging project should be entirely abandoned.

The campaign

He realized that this was no easy task, especially at that time when awareness of conservation concerns was very limited indeed. An unprecedented campaign was necessary. As a basis for it, Thilo considered that it was his duty to describe and explain what was at stake. Without convincing reasons the Society would have no chance of either drawing other individuals and NGOs into their “Save Sinharaja” campaign, or of getting the Government to listen to them.

Thilo now wrote the monograph titled The Sinharaja Forest 1972. The inclusion of the year in the title was meant to indicate the threat to this age-old natural system through human interference and its transitory status at that point of time. Here, also, for the first time a Ministry of the Environment was proposed. This remarkable work, published as a booklet by the WNPS, never attained later the prominence it deserves. It is reproduced here as Appendix VII.

Very little information about Sinharaja was then available. About the only record was a report by J. R. Baker in the Geograpbical journal titled The Sinharaja Rain forest of Ceylon”‘. Baker had camped in the vicinity of Sinharaja from the end of July to the beginning of September 1936, and visited the fringes of the forest. He wrote:

“The villagers in the vicinity of Sinharaja … are Buddhists … They hold the forest itself in great veneration and consider that any crime committed in it is particularly evil. The killing of animals and the eating of flesh are contrary to the precepts of Buddhism … For this reason pressure was brought to bear upon me not to place my camp actually within the forest.”

Thilo says in his monograph:

“The people of the Sinharaja country are friendly and hospitable. We were received in several houses and offered king coconut and hakuru.”

He also describes in detail the sustainable and limited use they made of forest produce. The area was very thinly populated with few villages and hamlets, accessible only on foot. Thus the peripheral human impact on the forest was negligible.

Two thousand copies in English and 1,000 in Sinhala of the booklet were printed. With its impact the WNPS managed to bring together a large number of NGOs for the sole purpose of opposing the logging of Sinharaja. Thilo wrote a memorandum addressed to the Prime Minister which was then co-signed by all those who lent their support.

It was the first time that so many different organizations were united in a single goal and acting together under one umbrella for conservation in Sri Lanka. Many NGOs supported the appeal to Government, among them the Soil Conservation Society of Ceylon, Geographical Society of Ceylon, Ceylon Natural History Society, National Agricultural Society and Planters’ Association.

The Ayurvedic Practitioners’ Association readily joined, as valuable and rare medicinal plants in Sinharaja make it a vital “Nature’s pharmacy”. Dr S. R. Kottegoda, Professor of Pharmacology and Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Ceylon, Colombo, also signed. Other well-known personalities in the list included former Conservators of Forests, Directors of Irrigation and Surveyors General, a few members of Parliament and journalists. The media also helped, to some extent.

Thilo realized the importance of involving the Buddhist clergy in the struggle, and sought, through Mr Sumith Abeywickrama of the Soil Conservation Society, the support of the Ven. Neluwe Gunananda Thero, Sanghanayaka of the Galle Pirivenas. The latter understandingly gave his full co-operation and associated himself with the document to the Prime Minister. The President of the All-Ceylon Buddhist Congress, Dr G. P. Malalasekera too was a signatory.

The main concerns expressed and arguments put forward in the memorandum were the following, in summary.

* Once it is mechanically logged natural regeneration will not take place, and it will be lost forever as a unique living monument of evolution.

*The evolution of the forest should continue for the sake of the gene pool. Once it is destroyed it could never be re-created by man.

*Only 9% of the wet zone in Sri Lanka is covered by forest. Experts state the extent should be 25%.

Sinharaja has not been studied systematically. It has a large number of indigenous species. It has great potential for study, research and new products from which prosperity may spring.

*Logging will affect the daily lives of people with ensuing flash floods and landslides. A good quality of life for the people is only possible in a high-quality environment.

The historic document (Appendix VIII) was submitted to Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike on 18 May 1972.

It was followed on June 5 by Hoffmann’s suggestions to the Ministry of Planning on how to meet the country’s need for timber. Some of the suggestions put forward were: study of the technology of rubber wood for its use in plywood; enrichment of 250,000 acres of degraded and secondary wet zone forest with mahogany, which is an all-purpose timber, and other useful species including quick-growing plywood timbers; temporary import of plywood logs for immediate relief if necessary; and an island-wide campaign for the planting of suitable tree species in home gardens, spare plots and wasteland.

The response

As a result of this opposition, the Government appointed a Committee, with George Rajapaksa, then Minister of Fisheries, as chairman. ‘There were hearings and deliberations. These went on for several years. ‘The WNPS, too, gave evidence. This, though crucial, is barely mentioned in the final report!

The Forest Department and its Ministry, as well as the Ministry of Industries and other interested parties, including the Canadian contractors, used all their very considerable powers and influence to convince the Government and the public that logging Sinharaja was in the overall greater interest of the nation. Canadian forestry experts were cited. An Indian botanist was brought down to argue and bolster the case for exploitation. Even socio-economic reasons were adduced to justify it.

The Canadians had claimed that with selective logging the forest would regenerate in 20 years. But at the rate of extraction needed for the supply of wood as required by the contract the entire extent of the wider Sinharaja forest would be gone through in 12 years. Yet the Indian agreed with their plan.

The position of the WNPS was steadily supported by Willem Meijer, a Dutch botanist with wide experience in the tropics and expert scientific knowledge of rain-forests. Then teaching at a university in the USA, he was in Sri Lanka to revise sections of Trimen’s Flora as the author of several of its chapters. He argued against the “experts” regarding the regrowth of the tropical trees at Sinharaja, which he estimated would take from 40 to 80 years, and he strongly warned against any disturbance to the unique forest”. The Indian botanist was countered by Hoffmann, in the article reproduced as Appendix IX.

All this was to no avail. The mechanized logging of the two Sinharaja Reserves began. It was claimed that those opposing it were cranks and obstructionists, who merely pursued an anti-national hobby. Thilo was once even threatened with bodily harm by the contractors.

The official publication of the report of the Rajapaksa Committee would be delayed until 1976.

However, since 1973 its contents were conveyed to the Press and the WNPS. It was a great disappointment. Most of it dealt with yield estimates, felling quotas, and the question of how and from which Reserves the enormous quantities of timber required by the Kosgama factory were to be procured. Ecological considerations seemed to be of no concern.

The report contended: “Re representatives of the Society (who) came before the committee, it was pointed out to them that in September 1970 their Society had agreed to the exploitation of Sinharaja provided an area not less than 1,000-1,200 acres was left in an undisturbed state, however between then and now the Society has changed its views considerably and repeatedly requested that the whole of Sinharaja should be set apart for purposes of scientific study.”

Already Hoffmann had written in The Sinharaja Forest the following passage which explained and represented the Society’s momentous change of view.

“Before visiting the area I believed the selective logging, as planned for the two Sinharaja reserves would be a sensible and acceptable economical measure. After days of careful observation in the field and subsequent study of the many factors involved, I have come to the firm conclusion that the two Sinharaja reserves should be left alone, and that they serve the nation best in their present, totally unexploited state.”

The Government report proposed that 4,200 acres in the Sinharaja Reserves should be left as an arboretum. But of this, as Hoffmann pointed out, not much more than 2,000 acres was intact rainforest: the rest had already been logged. As President of the WNPS Thilo Hoffmann continued the struggle with no letup, among other actions, writing several more persuasive and well-reasoned documents.

The continued pressure brought some relief The Prime Minister’s office informed the Society that there would be negotiations with the Canadian Government to modify the contract, for the time being to exploit only 1,500 acres at lesser intensity in the north-western part of the Sinharaja Reserves, and to carry out the mechanized logging first at the Delgoda and Morapitiya-Runakanda Reserves.

The General Committee of the WNPS, including its President, visited Sinharaja on March 8, 1975. Loris records “that they were deeply moved and greatly depressed by the permanent and irrevocable changes … inflicted.” The felling of each large tree in a rainforest destroys or damages smaller trees, other flora and fauna, along and around its line of fall. In addition, the wide “skid tracks” of the machinery to approach the trees and remove the timber had destroyed more of the forest.

These were then planted with mahogany, an exotic tree, in this unique indigenous ecosystem. (It is the area altered in this manner that is today mainly accessible to the visiting public.) They also:

noted with surprise that … the size of the authorized Pilot Project of 1,500 acres had been greatly exceeded. They were told that “an extension had been given” and that by now 3,000 acres have been logged, possibly even more.

As Hoffmann remarked, in the 22,000 acres of the two Sinharaja Reserves there was now “no more than 15,000, probably 10,000 acres only, of untouched quality forest left””. (That is, 6,000 and 4,000 ha, respectively.) Of this the State had agreed eventually to protect from logging, in effect, only 2,000 acres (or 800 ha), a simply insufficient, and vulnerable, area – representing a forest type which not long before had covered much of the low- and midlands of the country.

Sinharaja continued to be cut down without due control. The mechanized logging was not shifted to the other Reserves. A year later the outlook was grave, and the “heart of the forest”, as Hoffmann called it, was being destroyed.

After all the effort it seemed that the battle was lost. At this point Thilo wrote the paper entitled ‘Epitaph for a Forest: Sinharaja – 1976’ in Loris19 (Appendix XI) to yet again urge the attention of the public, persuade the State, and prevent the tragedy which today many find unthinkable.

The damage until now had been held back and slowed down by his relentless efforts. But if events continued to run their course the lucrative main logging contract would be extended, with Canadian aid. All the rest of Sinharaja would be destroyed.

In 1977 a new Government was elected. Thilo immediately tried to obtain a personal interview with the Prime Minister, J. R. Jayewardene. Fortunately, he succeeded very quickly. The latter’s Private Secretary, Nihal Weeratunge would always be helpful in conservation matters. Now politicians and administrators had become sufficiently aware of the continuous agitation to preserve Sinharaja and the reasons for it. At last, the persuasion met with a favourable reception and response.

Swiftly the State decreed that logging in the Sinharaja Reserves should cease entirely. It was decided that all wet-zone forests were to be given complete protection. The machinery and the vehicles were removed. The contractors departed. Sinharaja was saved.

Sinharaja today

Today Sinharaja is recognized as an important part of a `biological hotspot’, i. e. one of the areas of the Earth with the highest biological diversity, which Sri Lanka is assessed to be. It is the first natural feature in the country designated a World Heritage Site. An information brochure by the Forest Department describes Sinharaja as “the heart of the nation”. Had it been logged 35 years ago, as they wanted to, it would now be a severely degraded forest area, like so many others.

Thilo remarks: “I wished Sinharaja to be placed under the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance (Wildlife Department), because at that time only the status of National Park could give it the necessary legal protection. The Forest Department, of course, opposed this strongly, and eventually created its own rival to the Ordinance, namely the National Heritage Wilderness Area Act, for the sole purpose of keeping Sinharaja under its control. Under this Act Sinharaja was declared a National Wilderness Area in 1989. I believe since then no other area has been so declared by the FD.

In this connection it must be recalled that it was the Forest Department which used all the power, money and influence at its disposal to make sure that all of Sinharaja would be exploited for timber and to prevent it being preserved for posterity. They nearly succeeded!

Both the Department of Wildlife Conservation and particularly the Forest Department had their own agendas which often (and in the case of the FD, more often than not) were in plain opposition to sensible and effective conservation policies and projects. The title of the Head of the Forest Department, Conservator (now -General) of Forests, was actually a misnomer.

After the letter to the Prime Minister was submitted, the WNPS, under Hoffmann, had fought on unaided for the cause of Sinharaja. Even the co-signatories had been content to leave it at that. However, we find that even by 1978, as the Secretary of the Society wrote in his Annual Report, after the lonely seven-year battle by the WNPS “everybody else seems to be claiming credit for saving Sinharaja”!

In 1991 Thilo Hoffmann wrote in Loris20 of his endeavour: “This constitutes one of the few major victories which my direct personal involvement during over three decades in the conservation movement achieved. Only long after the battle was over did the Forest Department begin to realize the value of the untouched forest and started to give it meaningful protection and scientific study.

“A new law was promulgated, called the National Heritage Wilderness Areas Act (1985) and Sinharaja is today the only site declared under it. It has also received international recognition as a World Heritage Site (UNESCO). The logged portion of the forest offers interesting possibilities for scientific study about the effects of logging and regeneration whereas the major untouched portion of the forest remains a unique Sri Lanka system of inestimable value. I am confident that Sinharaja will now survive for all time and that the people of Sri Lanka will treasure it with the love and respect it deserves. The struggle was worth it.”

The largest untouched tropical rainforest in Ceylon, Sinharaja had taken at least 100 million years to evolve.

Features

Indian Ocean zone of peace torpedoed!

The US Navy’s torpedo attack on the Iranian frigate, IRIS Dena, on 4th March 2026, just outside Sri Lanka’s territorial waters, killed over 80 Iranian sailors. The Sri Lanka Navy rescued over 30 sailors and provided medical assistance for them in Galle while also recovering the floating corpses of the victims. Thereafter, a second Iranian naval vessel, the IRIS Bushehr, which also requested permission to dock, was permitted into Trincomalee by the Sri Lanka Navy, after separating its crew from the ship and bringing them to Colombo. A third ship, the IRIS Lavan, an amphibious landing vessel, requested to dock in the Southern Indian port of Cochin, with 183 crew, on the same day the Dena was attacked, and has been there since.

The US Navy’s torpedo attack on the Iranian frigate, IRIS Dena, on 4th March 2026, just outside Sri Lanka’s territorial waters, killed over 80 Iranian sailors. The Sri Lanka Navy rescued over 30 sailors and provided medical assistance for them in Galle while also recovering the floating corpses of the victims. Thereafter, a second Iranian naval vessel, the IRIS Bushehr, which also requested permission to dock, was permitted into Trincomalee by the Sri Lanka Navy, after separating its crew from the ship and bringing them to Colombo. A third ship, the IRIS Lavan, an amphibious landing vessel, requested to dock in the Southern Indian port of Cochin, with 183 crew, on the same day the Dena was attacked, and has been there since.

There are many aspects of these three incidents that have not been dealt with by the mainstream media, with any degree of seriousness, and warrants deeper analysis.

While the US and Iran are at war, the destruction of the frigate happened within Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone, but outside its territorial waters within which other countries, too, have rights of navigation. That is, this was far away from the main theatre of war in West Asia. But with this unprovoked attack in the Indian Ocean, the war and its consequences have come to Sri Lanka and India’s home-turf. The Dena was taking part in the MILAN 2026 naval exercise, organised by the Indian Navy, from 15th – 25th February, 2026, in which the US was also scheduled to take part, but, interestingly, withdrew from at the eleventh hour. One of the requirements of this exercise was for participating vessels to not carry ammunition. The Dena would have ordinarily been armed with various missiles and guns, including anti-ship missiles. Since the US was also supposed to take part in the exercise, this crucial information would also have been part of the US’s knowledge.

In this sense, it was an unprovoked attack against a ship that the US Navy knew well could not have defended itself. In real terms, this is no different from the US-Israeli alliance’s bombing of the girls’ school, ‘Shajareh Tayyebeh,’ in the town of Minab, in southern Iran, on 28th February, killing 165 people who were mostly children. Again, unprovoked and even worse, defenseless. In more recent times, President Trump has blamed this attack on the Iranians themselves, and as usual, without evidence.

The US attack changes the rules of the game. This establishes that any unarmed ship – military or otherwise – is fair game to any state which has the wherewithal to attack and get away with it. The US’s usual bravado, hero-centric narratives and talk of being fair in military contexts has been typified by countless Hollywood war movies, from Rambo to Sniper. However, US Secretary of Defence Pete Hegseth has clearly indicated the present reality and precedent when he noted the US would now ignore “stupid rules of engagement” and “[punch] them while they’re down.” Hegseth and the US war machine have now given Iran and anybody else who wishes to engage with the US, the same set of rules of engagement governed under the Law of the Jungle.

The sinking of the Iranian frigate, Colombo’s rescue of the victims and providing protection to the Bushehr and its crew, and India offering refuge to the IRIS Lavan and its crew but remaining silent about it until after the news on the Sri Lankan action broke out, open many questions for reflection.

All three ships had been invited by the Indian Navy to take part in an international exercise involving over 70 countries. The crew of the Dena had even paraded in the presence of the Indian President not too long before their untimely end. Having invited them to the exercise and given the hostile environment the unarmed Iranian vessels would have to face in the prevailing conditions of war, why did the Indian Navy or the country’s government not invite the Iranian ships to anchor in the relative safety of one of its harbors or even in Visakhapatnam itself where the exercise took place? This would have been a matter of political courtesy. On the other hand, did the Iranians even request such help from India except for the Lavan in the same way they asked the Sri Lankans? At the time of writing, we do not have clear answers to these crucial questions which have not been, by and large, raided in any serious way.

It is ironic that the attacks took place in a ‘zone of peace’. The resolution declaring the ‘Indian Ocean as a Zone of Peace’ was initially proposed by then Prime Minister of Ceylon Sirimavo Bandaranaike at the 1964 Non-Aligned Conference and was later adopted by the UN General Assembly as Resolution 2832 (XXVI) on 16th December 1971. Although the declaration was never taken seriously by the usual bandwagon of chronically belligerent states, particularly the US and the likes of China, France, Russia, UK, etc., violence as significant as the sinking of the Dena with its death toll and environmental consequences to the countries in the region, particularly to Sri Lanka, has not happened since the declaration.

The incident also took place within an area recent Indian foreign policy regards as its ‘neighbourhood’ under its ‘Neighbourhood First’ strategy, officially introduced in 2014. It is aimed at strengthening India’s ties with Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, the Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka guided by five basic principles which include Respect, Dialogue, Peace, Prosperity and Culture. Is it not surprising that India, with its unquestionable leadership in the region, could not prevent something this destructive in its own neighbourhood, or even offer help or protection after the naval exercise, to the beleaguered Iranians with whose country India has traditionally had a strong and long association? It is in this context that one can understand former Indian Foreign Minister Kanwal Sibal’s observation on X that “the US has ignored India’s sensitivities as the ship was in these waters because of India’s invitation.” It is disrespectful towards India, to say the least, when the country’s government has, in recent times, made herculean efforts to be included in the country club to which the US, Israel and other such nations belong.

Things look much worse against the backdrop of India’s deafening silence. For all its rhetoric, India comes off as small, insignificant and afraid in this situation which does not help if it still wishes to be taken seriously as an undisputed leader in the Global South. On the other hand, if the Indian government has completed its move in the direction of the Global North (obviously not geographically but politically) and wishes to be included within the rich, the powerful and the belligerent in the prevailing world order, then this positioning is correct. Perhaps, taken in India’s national interest, this is fair enough.

Unfortunately, however, the big boys in the ‘west’ do not still seem to consider India as an equal despite all it has to offer economically and all its efforts to be included in the big boys’ club. After all, Trump’s demand that India stop buying petroleum products from Russia, despite its cost-effectiveness, and only from US-declared sources, was accepted by India, without much resistance. Now, the US has declared that India has a window of 30 days to buy Russian oil, given the developing situation in the Strait of Hormuz because of the US-Israeli war. Unfortunately, this is not the way equals treat each other.

In this context, the following observation in the 8th March editorial of The Morning becomes pertinent and throws light on the instability and opaqueness of the region and its taken-for-granted positions of leadership in the global scheme of things: “India has, in the past, demonstrated a willingness to intervene diplomatically when foreign naval vessels, particularly those belonging to China, attempted to enter Sri Lankan ports. On several occasions, New Delhi has openly objected to Chinese research ships docking in Sri Lanka, arguing that such visits could have security implications for India.” This is not simply a reality but now standard diplomatic practice for India when dealing with Sri Lanka. As The Morning editorial further pointed out, “given that precedent, many observers are now asking a different question: why was there such silence when an American submarine was operating in close proximity to Sri Lanka and ultimately launched an attack that has transformed the region into a perceived conflict zone?

If India possesses the strategic awareness and diplomatic leverage to monitor the movements of Chinese vessels near Sri Lanka, surely it must also have been aware of the growing tensions involving the Iranian ship.”

It is into this situation that Sri Lanka has been reluctantly drawn in. Before the destruction of the Dena, the Sri Lankan government had been in contact with the frigate and Iranian officials in Colombo for 11 hours to work out how the Iranian ship could be given refuge in the country’s waters. Sri Lanka’s political Opposition in Parliament has blamed the government for the seemingly inordinate time taken to make this decision. It is during this time that the Dena was destroyed, causing mass casualties. While it would have been good if Sri Lanka acted earlier and saved more lives, things are not that simple. Sri Lanka found itself in a very difficult situation and without much local experience, or precedence, on how to deal with such conditions. After all, with a Navy, that is the smallest in the region, next to the Maldives, the country’s political leaders might have been rightly concerned that a country as belligerent as the US, with its naval assets in the ocean nearby, including the facilities in Diego Garcia merely 1776 km away might bomb Sri Lankan facilities, too.

After all, it is the belligerent and the powerful that call the shots in the existing world order, as they have done for centuries. If so, there is no way the country’s combined military could defend itself. And as has been made painfully apparent in recent years, there are no friends when push comes to shove. So, the time taken is understandable as a matter of caution, particularly when considering that Sri Lanka does not have standard operational procedures to deal with maritime emergencies of this kind. Besides, the Iranians were not invited to the area by the Sri Lankans but by Indians. The hosts by then had gone completely silent.

Dealing with the situation of the second ship, the Bushehr has also not been easy. As the Sri Lankan President noted in his press conference on 5th March, the docking request for the Bushehr was “described as a visit to enhance cooperation.” Further as he noted, “as everyone knows, a cooperation visit does not take place in such a manner; it requires extensive formal procedures. Therefore, we were studying those procedures.” Obviously, the Iranians were attempting to minimise the military nature of their ships and gain access to Sri Lankan ports on a pretext such as technical difficulties rather than directly making it clear that they needed protection in a situation of war. But this pretext is to fulfill a technical legal requirement. It is very likely that the Iranians were trying to use the practices of customary international law and 1907 Hague Convention (XIII) based upon the principle of force majeure (unavoidable accident or superior force), providing for humanitarian exceptions to the strict prohibition against using the waters of neutral countries.

It is to the credit of the Sri Lankan government that it acted decisively, soon after the Dena was destroyed, by rapidly dispatching its Navy to conduct rescue and recovery operations and also by separating the crew of 208 from the Bushehr and dispatching them to two different harbours. By doing so, Sri Lanka, perhaps unknowingly, has come up with operational procedures that can be used in situations like this in the future. That is, ensuring that the crew and the ship were no longer militarily engaged and under direct Sri Lankan control rather than the Iranians and, therefore, hopefully not a target of yet another US attack. While the Dena rescue was ongoing, the Indian Navy had issued a list of actions it had taken, including naming the types of vessels and aircraft it had dispatched to aid in the search but never mentioning the US attack. If the intention was to show that they were not sitting idly by, this was too little and too late. The Lankan Navy, despite its size, is perfectly capable of running a rescue operation of this kind in its own backyard after years of experience throughout the civil war. Besides, there is no indication that the Sri Lankan Navy had asked for outside help.

Intriguingly, all this while there was no news from the Indian Navy or its government of the Lavan requesting to dock in Cochin as early as 28th February or that it had in fact reached that harbour on 5th March and its crew accommodated in Indian naval facilities which was the right thing to do. All this information literally trickled out only after the destruction of the Dena, the rescue of its survivors and safeguarding of the Bushehr and its crew by the Sri Lankans had hit international headlines with considerable positivity. It almost seems as if the Indian Navy and its government were waiting to see the potential consequences of the Sri Lankan action, prior to making their own action known, despite already having done what was right.

The Sri Lankan President was also at pains to reiterate the neutrality of the country for obvious reasons. After all, if the current war situation is to be considered even superficially, the clearest point it makes is that the world’s most powerful countries are led by mad men with no sense of ethics or empathy. As he noted, “our position has been to safeguard our neutrality while demonstrating our humanitarian values.” He further noted, “amidst all this, as a government, we have intervened in a manner that safeguards the reputation and dignity of our country, protects human lives and demonstrates our commitment to international conventions. That intervention is currently ongoing … We do not act in a biased manner towards any state, nor do we submit to any state … we firmly believe that this is the most courageous and humanitarian course of action that a state can take.” The government also has been cautious to be guided by customary international law, the 1907 Hague Convention (XIII) as well as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea as subsequent declarations have indicated. After a long time, Sri Lankan action with global consequences sounds both statesmanlike and very Buddhist.

Here, I agree with the President without reservation. This is the only way Sri Lanka could have acted in this situation in a world of relative inaction and a regional context marked by uncomfortable silence.

This is a good illustration of independence and statesmanship by a small state even under very difficult conditions. Hopefully, the government will continue on this path in other instances, too, that is, not to “submit to any state” despite pressure and provocation. It must become a necessary part of Sri Lanka’s international and national policy framework governing all actions.

Features

Humanitarian leadership in a time of war

There has been a rare consensus of opinion in the country that the government’s humanitarian response to the sinking of Iran’s naval ship IRIS Dena was the correct one. The support has spanned the party political spectrum and different sections of society. Social media commentary, statements by political parties and discussion in mainstream media have all largely taken the position that Sri Lanka acted in accordance with humanitarian principles and international law. In a period when public debate in Sri Lanka is often sharply divided, the sense of agreement on this issue is noteworthy and reflects positively on the ethos and culture of a society that cares for those in distress. A similar phenomenon was to be witnessed in the rallying of people of all ethnicities and backgrounds to help those affected by the Ditwah Cyclone in December last year.

The events that led to this situation unfolded with dramatic speed. In the early hours before sunrise the Dina made a distress call. The ship was one of three Iranian naval vessels that had taken part in a naval gathering organised by India in which more than 70 countries had participated, including Sri Lanka. Naval gatherings of this nature are intended to foster professional exchange, confidence building and goodwill between navies. They are also governed by strict protocols regarding armaments and conduct.

When the exhibition ended open war between the United States and Iran had not yet broken out. The three Iranian ships that participated in the exhibition left the Indian port and headed into international waters on their journey back home. Under the protocol governing such gatherings ships may not be equipped with offensive armaments. This left them particularly vulnerable once the regional situation changed dramatically, though the US Indo-Pacific Command insists the ship was armed. The sudden outbreak of war between the United States and Iran would have alerted the Iranian ships that they were sailing into danger. According to reports, they sought safe harbour and requested docking in Sri Lanka’s ports but before the Sri Lankan government could respond the Dena was fatally hit by a torpedo.

International Law

The sinking of the Dena occurred just outside Sri Lanka’s territorial waters. Whatever decision the Sri Lankan government made at this time was bound to be fraught with consequence. The war that is currently being fought in the Middle East is a no-holds-barred one in which more than 15 countries have come under attack. Now the sinking of the Dena so close to Sri Lanka’s maritime boundary has meant that the war has come to the very shores of the country. In times of war emotions run high on all sides and perceptions of friend and enemy can easily become distorted. Parties involved in the conflict tend to gravitate to the position that “those who are not with us are against us.” Such a mindset leaves little room for neutrality or humanitarian discretion.

In such situations countries that are not directly involved in the conflict may wish to remain outside it by avoiding engagement. Foreign Minister Vijitha Herath informed the international media that Sri Lanka’s response to the present crisis was rooted in humanitarian principles, international law and the United Nations. The Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) which was adopted 1982 provides the legal framework governing maritime conduct and obliges states to render assistance to persons in distress at sea. In terms of UNCLOS, countries are required to render help to anyone facing danger in maritime waters regardless of nationality or the circumstances that led to the emergency. Sri Lanka’s response to the distress call therefore reflects both humanitarianism and adherence to international law.

Within a short period of receiving the distress message from the stricken Iranian warship the Sri Lankan government sent its navy to the rescue. They rescued more than thirty Iranian sailors who had survived the attack and were struggling in the water. The rescue operation also brought to Sri Lanka the bodies of those who had perished when their ship sank. The scale of the humanitarian challenge is significant. Sri Lanka now has custody of more than eighty bodies of sailors who lost their lives in the sinking of the Dena. In addition, a second Iranian naval ship IRINS Bushehr with more than two hundred sailors has come under Sri Lanka’s protection. The government therefore finds itself responsible for survivors but also for the dignified treatment of the bodies of the dead Iranian sailors.

Sri Lanka’s decision to render aid based on humanitarian principles, not political allegiance, reinforces the importance of a rules-based international order for all countries. Reliance on international law is particularly important for small countries like Sri Lanka that lack the power to defend themselves against larger actors. For such countries a rules-based international order provides at least a measure of protection by ensuring that all states operate within a framework of agreed norms. Sri Lanka itself has played a notable role in promoting such norms. In 1971 the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution declaring the Indian Ocean a Zone of Peace. The initiative for this proposal came from Sri Lanka, which argued that the Indian Ocean should be protected from great power rivalry and militarisation.

Moral Beacon

Unfortunately, the current global climate suggests that the rules-based order is barely operative. Conflicts in different parts of the world have increasingly shown disregard for the norms and institutions that were created in the aftermath of the Second World War to regulate international behaviour. In such circumstances it becomes even more important for smaller countries to demonstrate their commitment to international law and to convert the bigger countries to adopt more humane and universal thinking. The humanitarian response to the Iranian sailors therefore needs to be seen in this wider context. By acting swiftly to rescue those in distress and by affirming that its actions are guided by international law, Sri Lanka has enhanced its reputation as a small country that values peace, humane values, cooperation and the rule of law. It would be a relief to the Sri Lankan government that earlier communications that the US government was urging Sri Lanka not to repatriate the Iranian sailors has been modified to the US publicly acknowledging the applicability of international law to what Sri Lanka does.

The country’s own experience of internal conflict has shaped public consciousness in important ways. Sri Lanka endured a violent internal war that lasted nearly three decades. During that period questions relating to the treatment of combatants, the protection of civilians, missing persons and accountability became central issues. As a result, Sri Lankans today are familiar with the provisions of international law that deal with war crimes, the treatment of wounded or disabled combatants and the fate of those who go missing in conflict. The country continues to host an international presence in the form of UN agencies and the ICRC that work with the government on humanitarian and post conflict issues. The government needs to apply the same principled commitment of humanitarianism and the rule of law to the unresolved issues from Sri Lanka’s own civil war, including accountability and reconciliation.

By affirming humanitarian principles and acting accordingly towards the Iranian sailors and their ship Sri Lanka has become a moral beacon for peace and goodwill in a world that often appears to be moving in the opposite direction. At a time when geopolitical rivalries are intensifying and humanitarian norms are frequently ignored, such actions carry symbolic significance. The credibility of Sri Lanka’s moral stance abroad will be further enhanced by its ability to uphold similar principles at home. Sri Lanka continues to grapple with unresolved issues arising from its own internal conflict including questions of accountability, justice, reparations and reconciliation. It has a duty not only to its own citizens, but also to suffering humanity everywhere. Addressing its own internal issues sincerely will strengthen Sri Lanka’s moral standing in the international community and help it to be a force for a new and better world.

BY Jehan Perera

Features

Language: The symbolic expression of thought

It was Henry Sweet, the English phonetician and language scholar, who said, “Language may be defined as the expression of thought by means of speech sounds“. In today’s context, where language extends beyond spoken sounds to written text, and even into signs, it is best to generalise more and express that language is the “symbolic expression of thought“. The opposite is also true: without the ability to think, there will not be a proper development of the ability to express in a language, as seen in individuals with intellectual disability.

Viewing language as the symbolic expression of thought is a philosophical way to look at early childhood education. It suggests that language is not just about learning words; it is about a child learning that one thing, be it a sound, a scribble, or a gesture, can represent something else, such as an object, a feeling, or an idea. It facilitates the ever-so-important understanding of the given occurrence rather than committing it purely to memory. In the world of a 0–5-year-old, this “symbolic leap” of understanding is the single most important cognitive milestone.

Of course, learning a language or even more than one language is absolutely crucial for education. Here is how that viewpoint fits into early life education:

1. From Concrete to Abstract

Infants live in a “concrete” world: if they cannot see it or touch it, it does not exist. Early education helps them to move toward symbolic thought. When a toddler realises that the sound “ball” stands for that round, bouncy thing in the corner, they have decoded a symbol. Teachers and parents need to facilitate this by connecting physical objects to labels constantly. This is why “Show and Tell” is a staple of early education, as it gently compels the child to use symbols, words or actions to describe a tangible object to others, who might not even see it clearly.

2. The Multi-Modal Nature of Symbols

Because language is “symbolic,” it does not matter how exactly it is expressed. The human brain treats spoken words, written text, and sign language with similar neural machinery.

Many educators advocate the use of “Baby Signs” (simple gestures) before a child can speak. This is powerful because it proves the child has the thought (e.g., “I am hungry”) and can use a symbol like putting the hand to the mouth, before their vocal cords are physically ready to produce the word denoting hunger.

Writing is the most abstract symbol of all: it is a squiggle written on a page, representing a sound, which represents an idea or a thought. Early childhood education prepares children for this by encouraging “emergent writing” (scribbling), even where a child proudly points to a messy circle that the child has drawn and says, “This says ‘I love Mommy’.”

3. Symbolic Play (The Dress Rehearsal)

As recognised in many quarters, play is where this theory comes to life. Between ages 2 and 3, children enter the Symbolic Play stage. Often, there is object substitution, as when a child picks up a banana and holds it to his or her ear like a telephone. In effect, this is a massive intellectual achievement. The child is mentally “decoupling” the object from its physical reality and assigning it a symbolic meaning. In early education, we need to encourage this because if a child can use a block as a “car,” they are developing the mental flexibility required to later understand that the letter “C” stands for the sound of “K” as well.

4. Language as a Tool for “Internal Thought”

Perhaps the most fascinating fit is the work of psychologist Lev Vygotsky, who argued that language eventually turns inward to become private speech. Have you ever seen a 4-year-old talking to himself or herself while building a toy tower? “No, the big one goes here….. the red one goes here…. steady… there.” That is a form of self-regulation. Educators encourage this “thinking out loudly.” It is the way children use the symbol system of language to organise their own thoughts and solve problems. Eventually, this speech becomes silent as “inner thought.”

Finally, there is the charming thought of the feasibility of conversing with very young children in two or even three or more languages. In Sri Lanka, the three main languages are Sinhala, Tamil and English. There are questions asked as to whether it is OK to talk to little ones in all three languages or even in two, so that they would learn?

According to scientific authorities, the short, clear and unequivocal answer to that query is that not only is it “OK”, it is also a significant cognitive gift to a child.

In a trilingual environment like Sri Lanka, many parents worry that multiple languages will “confuse” a child or cause a “speech delay.” However, modern neuroscience has debunked these myths. The infant brain is perfectly capable of building three or even more separate “lexicons” (vocabularies) simultaneously.

Here is how the “symbolic expression of thought” works in a multilingual brain and how we can manage it effectively.

a). The “Multiple Labels” Phenomenon

In a monolingual home, a child learns one symbol for an object. For example, take the word “Apple.” In a Sri Lankan trilingual home, the child learns three symbols for that same thought:

* Apple (English)

* Apal

(Sinhala – ඇපල්)

* Appil

(Tamil – ஆப்பிள்)

Because the trilingual child learns that one “thought” can be expressed by multiple “symbols,” the child’s brain becomes more flexible. This is why bilingual and trilingual children often score higher on tasks involving “executive function”, meaning the ability to switch focus and solve complex problems.

b). Is there a “Delay”?

(The Common Myth)

One might notice that a child in a trilingual home may start to speak slightly later than a monolingual peer, or they might have a smaller vocabulary in each language at age two.

However, if one adds up the total number of words they know across all three languages, they are usually ahead of monolingual children. By age five, they typically catch up in all languages and possess a much more “plastic” and adaptable brain.

c). Strategies for Success: How to Do It?

To help the child’s brain organise these three symbol systems, it helps to have some “consistency.” Here are the two most effective methods:

* One Person, One Language (OPOL), the so-called “gold standard” for multilingual families.

Amma

speaks only Sinhala, while the Father speaks only English, and the Grandparents or Nanny speak only Tamil. The child learns to associate a specific language with a specific person. Their brain creates a “map”: “When I talk to Amma, I use these sounds; when I talk to Thaththa, I use those,” etc.

*

Situational/Contextual Learning. If the parents speak all three, one could divide languages by “environment”: English at the dinner table, Sinhala during play and bath time and Tamil when visiting relatives or at the market.

These, of course, need NOT be very rigid rules, but general guidance, applied judiciously and ever-so-kindly.

d). “Code-Mixing” is Normal

We need not be alarmed if a 3-year-old says something like: “Ammi, I want that palam (fruit).” This is called Code-Mixing. It is NOT a sign of confusion; it is a sign of efficiency. The child’s brain is searching for the quickest way to express a thought and grabs the most “available” word from their three language cupboards. As they get older, perhaps around age 4 or 5, they will naturally learn to separate them perfectly.

e). The “Sri Lankan Advantage”

Growing up trilingual in Sri Lanka provides a massive social and cognitive advantage.

For a start, there will be Cultural Empathy. Language actually carries culture. A child who speaks Sinhala, Tamil, and English can navigate all social spheres of the country quite effortlessly.

In addition, there are the benefits of a Phonetic Range. Sinhala and Tamil have many sounds that do not exist in English (and even vice versa). Learning these as a child wires the ears to hear and reproduce almost any human sound, making it much easier to learn more languages (like French or Japanese) later in life.

As an abiding thought, it is the considered opinion of the author that a trilingual Sri Lanka will go a long way towards the goals and display of racial harmony, respect for different ethnic groups, and unrivalled national coordination in our beautiful Motherland. Then it would become a utopian heaven, where all people, as just Sri Lankans, can live in admirable concordant synchrony, rather than as splintered clusters divided by ethnicity, language and culture.

A Helpful Summary Checklist for Parents

* Do Not Drop a Language:

If you stop speaking Tamil because you are worried about English, the child loses that “neural real estate.” Keep all three languages going.

* High-Quality Input:

Do not just use “commands” (Eat! Sleep!). Use the Parentese and Serve and Return methods (mentioned in an earlier article) in all the languages.

* Employ Patience:

If the little one mixes up some words, just model the right words and gently correct the sentence and present it to the child like a suggestion, without scolding or finding fault with him or her. The child will then learn effortlessly and without resentment or shame.

by Dr b. J. C. Perera

by Dr b. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paediatrics), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony.

FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoUniversity of Wolverhampton confirms Ranil was officially invited

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoLegal experts decry move to demolish STC dining hall

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoFemale lawyer given 12 years RI for preparing forged deeds for Borella land

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoCabinet nod for the removal of Cess tax imposed on imported good

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoLibrary crisis hits Pera university

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA