Opinion

Random reflections on some conversations with Prof. Jayathilake

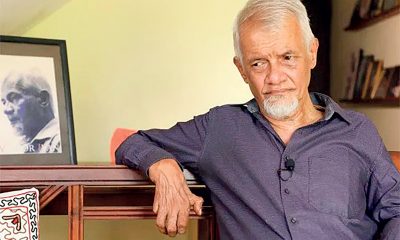

By Prof. Priyan Dias,

Emeritus Professor in Civil Engineering (University of Moratuwa); Consultant/Professor, Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology; and Fellow, National Academy of Sciences of Sri Lanka

It is a year since the passing of Professor Lakshman Jayathilake, a Peradeniya University Emeritus Professor in Mechanical Engineering. Apart from his professorial role, he was also Vice-Chancellor of Peradeniya University, Chairman of the University Grants Commission and Chairman of the National Education Commission. He was an educationist to the hilt. Although in a different engineering faculty and from a different engineering discipline, and also junior to him by over a decade, the limited number of interactions I had with him were always thought provoking. Even before I met him, I was aware of his impeccable engineering pedigree, having worked for his PhD at Imperial College, London, under Professor Brian Spalding (FRS, FREng), known then as the Grand Old Man of Computational Fluid Dynamics. Later, he became interested in the Systems Thinking and Practice pioneered by Peter Checkland at Lancaster University. It is this interest in systems that first brought us together, after I heard one of his talks on the subject – I now happen to be an Associate Editor of Civil Engineering and Environmental Systems.

We once had to travel to Anuradhapura and back in a day, to inspect the Jethawaranamaya, which was exhibiting large cracks at the time, for Prof. Jayathilake to comment on the moisture movement within the structure, and myself to opine on its structural integrity. While passing Kurunegala on our return, he mentioned that there was a village school in the district where students were trained to speak very good English. He was quick to point out however, that English proficiency alone would not guarantee employment or upward mobility, since that depended on social connections as well. It is not that he did not see the great value of learning to operate in English, but he was well aware of the various divisions that language brought within our country. When I once wondered aloud at a meeting in his presence whether the teaching of engineering solely in English stifled student creativity, he was quick to acknowledge the problem. At any rate, we need our collective wisdom to tackle our language problems in Sri Lanka – something that Prof. Jayathilake was keenly aware of and did his best to ameliorate.

Also, on our return from Anuradhapura, Professor Jayathilake pointed out a police station from which he had to effect the release of some JVP affiliated student activists – ‘so called heroes’ he called them. Many Vice-Chancellors have had to spend time in police stations to rescue JVP oriented student activists. Very few, if any, have done that for LTTE oriented ones. And there lies a difference that still haunts our land. Both the JVP and LTTE were branded as terrorist organisations during their ‘active’ days. However, largely as a result of ‘Colombo Society’ becoming aware of the impoverishment of southern JVP youth (recall the phrase Kolombata kiri, Gamata kekiri ‘Milk for Colombo, (lowly) melons for the village’), they have largely become integrated into mainstream society – causing the JVP revolution to be seen not as an aberration of, but a corrective to, the body politic, with many of today’s JVP MPs commanding widespread respect. This change of perspective was due in no small measure to the Report on the Presidential Commission Youth (1990), in fact chaired by none other than Professor Lakshman Jayathilake. Together with him, Professors G.L. Peiris and Arjuna Aluwihare were also involved in discussions with these southern youth who had been ‘left behind’ by society. As a young academic at that time, I looked up to them as genuine heroes – academics who left their ivory towers to solve the messy problems of our nation. In my opinion, however, we missed the opportunity to have another Youth Commission to hear the grievances of the northern youth after the crushing of the LTTE uprising. I said as much when I made representations to the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC). As a result, there is no corresponding sympathy for the plight of impoverished northerners, the ‘national question’ remains unanswered, the LTTE maintains its ‘terrorist’ brand (while the JVP has shed its), and talented Tamil citizens, who two generations ago contributed to the development of Malaysia and Singapore, today give their hearts, minds and energies to Canada and Australia.

Days after the Boxing day tsunami of 2004, when I was wondering how an engineering academic like myself could be relevant at that time of national calamity, I had a phone call from Professor Jayathilake, urging me as a structural engineering academic to study the performance of tsunami affected structures, so that we could ‘build back better’. That led to me and other colleagues documenting and analysing such tsunami induced structural failures. The Society of Structural Engineers, Sri Lanka was able to issue its Guidelines for Buildings at Risk from Natural Disasters as a result of this work, later adopted by the Disaster Management Centre and the National Building Research Organization. One of the resulting technical papers won a prize from the Institution of Civil Engineers, U.K. – Professor Ranjith Dissanayake, the current President-elect of the Institution of Engineers, Sri Lanka, was a co-author. Two other young graduates who helped me with this work are now engineering professors at Peradeniya (Hiran Yapa) and Moratuwa (Chinthaka Mallikarachchi). Tsunami resilience work in Sri Lanka continues to this day, with significant Sri Lankan contributions to the global knowledge base, among which is a University College London initiative led by Professor Tiziana Rossetto and involving Dr Ajith Thamboo (South Eastern University of Sri Lanka) and Prof. Kushan Wijesundara (Peradeniya University), with logistical support from the National Academy of Sciences of Sri Lanka. I should also mention my Moratuwa University colleague and good friend from school days, the late Professor Samantha Hettiarachchi, who spearheaded the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System. Professor Dilanthi Amaratunga, based in the U.K., has given leadership in the socio-economic resilience aspects. I note that the National Science Foundation intends to have a 20th anniversary symposium on the subject in December 2024, probably involving oceanographer Prof. Charitha Pattiaratchi from the University of Western Australia.

Towards the end of his career, Professor Jayathilake identified himself with two emerging universities, serving as the Dean of the Engineering Faculty at the University of Ruhuna, and as the Chancellor of the Wayamba University. That was typical of the man – using his not inconsiderable stature to help emerging institutions. Lakshman Jayathilake has gone the way of all the earth, but those whose lives were touched by his have doubtless benefitted through their engagement with a multi-dimensional human being. I am blessed to have interacted with him, even in a small way.

Opinion

Jamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

Political commentators have long been divided over the role of U.S. President Donald Trump, particularly following what critics describe as the first-ever sudden military aggression against a sovereign state by a legitimate military force involving direct attacks on security and civilian targets and the kidnapping a country’s legitimate ruler. This act stands in sharp contrast to conventional invasions that were previously justified through various false pretenses. Accordingly, there is little debate that the invasion of Venezuela and the kidnapping of President Nicolás Maduro represents a fundamentally different situation—a new beginning—when compared with the conventional invasion of Iraq and the capture of President Saddam Hussein, or the invasion of Libya and the killing of President Muammar Gaddafi.

It is also evident that this incident marks a clear departure from the long-standing strategies employed against Cuba for more than sixty years and against Venezuela for over a decade, which relied on sanctions, covert operations, and political pressure to subjugate governments and societies or engineer regime change. Although this new model constitutes a serious violation of the United Nations Charter, the UN has failed to take any meaningful action, thereby severely undermining its role and credibility. In the past, when sanctions were imposed on Cuba, leaders from a majority of countries mobilised to submit resolutions to the UN General Assembly and exert pressure on the United States. Under the present circumstances, however, there has been no significant intervention by member states to demand that the UN condemn the kidnapping of President Nicolás Maduro and secure his immediate release.

Such silence, particularly at a time when global public opinion increasingly portrays Donald Trump as operating like a leader of a underworld network, sets a deeply troubling precedent. Consequently, the public has begun to question whether Trump’s new approach has succeeded in imposing psychological barriers on other world leaders who openly challenge American imperialism. Beyond violating the UN Charter by acting as the head of what critics describe as a “terrorist state,” Trump has also imposed psychological pressure on the UN’s own bureaucratic structure by deliberately weakening its institutional foundations.

This strategy is further confirmed by Trump’s announcement that the United States would withdraw from thirty-one United Nations bodies and thirty-five other international conventions and organisations, while also terminating financial contributions. These decisions effectively signal that U.S. solidarity with the international community on climate change, world peace, and democratic governance is no longer a priority.

Earlier funding cuts to the World Health Organization have already forced it to rely heavily on corporate financing. Given the WHO’s significant authority over global food and pharmaceutical markets—and its power to shape the world economy during pandemics—this dependency has created conditions in which global health governance can be heavily influenced by the commercial interests of multinational corporations and billionaires. Research presented by Dr. David Bell indicates that global health regulations during the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to the closure of approximately 200,000 small businesses worldwide while simultaneously creating 40 new billionaires. There is little doubt that the United Nations will face a similar fate under sustained financial pressure.

This trajectory suggests that the United Nations, too, may be compelled to operate increasingly in accordance with the interests of global billionaires. The Public–Private Partnership Agreement signed between the UN and the World Economic Forum in 2019 further reinforces this concern. Following this agreement, the World Economic Forum, meeting in Davos in 2020, advanced the concept of the “Great Reset,” arguing that the world must be re-established through global multilateral institutional systems.

Implicit in this vision is the notion that before the world can be “reset,” it must first be disrupted, Jammed or effectively dismantled.

The World Economic Forum has also promoted the idea of establishing a new form of global governance system through such disruption. Critics argue that the ultimate objective of this strategy is the creation of a “Global Government” controlled by the world’s billionaires. This structure is widely viewed as an extension of the existing global level decision-making system often referred to as the “Deep State,” which operates above sovereign governments. This so-called parastate is understood to consist of entrenched senior officials, intelligence agencies, military leadership, and some corporate actors functioning beyond the authority of democratically elected leaders.

As such a strong global perception has emerged that this parastate is dominated by a small group of roughly one hundred billionaires and reinforced by a network of global media institutions under their influence. At times, President Trump has strategically accused certain U.S. officials of representing this parastate in an effort to distance himself from similar accusations. However, the electoral process that brought him to power, along with the major policy decisions he implemented thereafter, have revealed a close alignment between his administration and the interests of this new global power structure. Increasingly, independent critics argue that Trump himself has functioned as the shadow executive of this global parastate. His rise to power is seen as a critical precondition for advancing the final phase of a broader global roadmap aimed at dismantling and reconstructing the world order. In this interpretation, Trump’s role was to elevate the operational capacity of this system—previously managed more discreetly by other U.S. presidents—to an unprecedented level of intensity.

This transformation of American imperialism was vividly reflected in Trump’s military actions against Venezuela. Initially, familiar tactics were deployed, including economic sanctions, drug-trafficking accusations, naval provocations and arrest of vessels by Coast Guard and unilateral legal actions against President Maduro under the pretext of internal security. Such measures are consistent with long-standing U.S. practices toward states perceived as geopolitical or economic challengers.

However, in the cases of Venezuela and Cuba, political defiance, and close relations with China and Russia have also played decisive roles. The anti-imperialist political identity of leaders in these countries has inspired resistance movements worldwide, which is also explaining the deep hostility directed toward them by U.S. policymakers. Through the kidnapping of President Maduro, Trump sent a stark warning to other anti-imperialist leaders—an unmistakable act of psychological warfare carried out with unprecedented openness.

However, for the parastate to dismantle and rebuild the world as envisioned, a crucial condition must be met which is the restoration of a unipolar world order similar to that which emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1992. This requires weakening or geopolitically constraining the economic and military power of China and Russia. To achieve this, pro-Chinese and pro-Russian states—particularly those rich in natural resources or located in strategic regions—must be destabilised, subjected to crises, and subjected to regime change. The culmination of this process would involve widespread military tension and a severe global economic crisis, making destruction a prerequisite for reconstruction.

When viewed within this broader framework, Trump’s global strategy becomes more coherent. Russia has been drawn into a prolonged conflict in Ukraine, while China faces escalating military pressure around Taiwan and the South China Sea created through U.S. alliances with Japan and the Philippines.

Simultaneously, renewed efforts are underway to reassert U.S. dominance over Latin America and the Caribbean by disrupting their economic and military relations with China, Russia, and even the European Union—reviving a modernised version of the Monroe Doctrine. At present in those counties US is having highest foreign investment, but China is the largest trading Partners. However, Trump’s use of tariffs as political weapons, often in violation of World Trade Organization principles, further exaggerates this situation.

Trumps interest in acquiring Greenland must also be understood within this strategic context. Greenland’s geographic position between the U.S. and Russia, its growing importance in Arctic shipping routes, and its vast natural resources make it a key geopolitical asset. The expansion of Russian military infrastructure in the Arctic and increased Chinese economic engagement have further heightened strategic value of Greenland. Under the 1951 U.S.–Greenland defense agreement, American military installations and missile- monitoring systems already operate on the island. Beyond military considerations, Greenland’s estimated US$4 trillion worth of oil, gas, and rare-earth resources are critical in light of China’s restrictions on rare- earth exports when have intensified U.S. interest, particularly following the escalation of the trade war in May 2025.

Meanwhile, Trump’s proposal to financially incentivise Greenland’s population to sever ties with Denmark to be annexed to US underscores how sovereign states may be divided and annexed under future strategies driven by global economic elites. Such actions also threaten the stability of NATO, an alliance in which the U.S. bears approximately 70% of defence costs, placing Europe at significant risk of severe conflicts between member countries. Ultimately, these developments highlight the growing role of parastate actors in dismantling existing political, economic, and security systems in to the world to facilitate a billionaire- controlled global order. In that process through funding cuts, public–private partnerships, political manipulation, intelligence operations, and engineered crises, sovereign states are weakened and destabilised. Examples from geopolitically sensitive regions, including Sri Lanka, illustrate how economic collapse and political fragmentation can be externally induced.

The invasion of Venezuela and the kidnapping of its legitimate leader signal a dangerous escalation in this process. Ongoing destabilisation efforts in Iran, coupled with rising tensions in the Middle East and volatility in global energy markets, further increase the risk of worldwide economic and military catastrophe which could be the ultimate precondition for the so called Great-Reset of the world. In this context, sovereign states and the global community must align in the Pretext of Preventing a third world war and recognising the urgent need for an alternative, genuinely independent multilateral institutional system to undermine the ultimate grand strategy of the deep state. In that process the bottom line must be to reverse the unprecedented approach of the President Donald Trump by condemning military aggression in Venezuela and demanding the release of the President Nicolas Maduro immediately.

by Dr. K. M. Wasantha Bandara

Secretary

Patriotic National Movement

Opinion

A beloved principal has departed!

“When the principal sneezes, the whole school catches a cold. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the truth. The principal’s impact is significant; his focus becomes the school’s focus.” These are Whitaker’s words and they illustrate the predominant role that a principal has to execute in a school. The Wallace Foundation has identified the following as the five key responsibilities of a school principal.

- Establishing a school wide vision of commitment to high standards and success of all students.

- Ensuring that learning is at the centre of all activities.

- Cultivating leadership in others

- Improving achievement by focusing on the quality of instruction.

- Managing people and resources at hand.

Rev. Fr. Stephen Abraham is one such principal who fulfilled these commitments at the highest level possible at St. Anthony’s College, Katugastota, for a period of 15 years from 1979 to 1994. He was born on the 15th of February 1933 and ordained a Priest in the Benedictine Order of the Catholic Church on 17 December 1964. His demise was on 21st February 2026, on the fourth day of the period of lent in the catholic calendar. As such he has been in the service of God as a priest for 62 years of his life of 93 years. This article contains extracts from a piece that I wrote when he celebrated the Golden Jubilee of his priesthood in December 2014.

St. Anthony’s College went through a burdensome period after the handing over of the school to the government as the teachers, support staff and parents were baffled about the direction of the school. It is at this stage that Fr. Stephen was appointed as the Principal. In his own inimitable manner he took control with authority and raised the confidence of the staff and the community. This was needed as the confidence was at its lowest ebb and he had the vision to realise that boosting the level of confidence had to be the priority. As the famous quote says “A good leader inspires others with confidence in him; a great leader inspires them with confidence in themselves”. He could not have done this without self-confidence which he had in abundance. Alongside, he laid his emphasis on maintaining a strict code of discipline as it had degraded due to the unfortunate incidents paving way for the handing over of the school.

A quality that any good principal should possess is to be a great communicator. Fr. Stephen had a natural ability to be dexterous with people. He made connections with each person showing them that he cares about their own situations. Through these connections he set high expectations for each individual letting them know that they cannot get away with mediocrity. The articulation and eloquence of his expression convinced people of his opinions and decisions. He is blessed with a sound sense of humour and it helped to ease tensions and resolve conflicting situations. More importantly, he was passionate about his responsibilities as the head of the school and he spent all his time and energy with the sole objective of creating a proper environment for the students to be responsible learners striving for personal excellence. Fr. Stephen was everywhere in the school and knew everything that was happening within the premises and he made himself visible at all times. He fits well with the description of a leader in Harold Seymour’s quotation “Leaders are the ones who keep faith with the past, keep step with the present, and keep the promise to posterity”. No wonder therefore, that he is considered as an outstanding principal.

In 1979 when the school celebrated its 125th anniversary, Fr. Stephen invited His Excellency the President J. R. Jayewardene as the chief guest of the Prize Giving ceremony. His emphasis on discipline is highlighted through this excerpt from his speech at this function. “The progress of any society depends mainly on discipline and discipline is not come by so easily unless the members of the society work towards it. No nation can be great unless its students aspire to greatness. But all this calls for training which is impossible without quality in teaching. Teachers should command the greatest respect in the land. Teaching is not a mere avocation, it is indeed a vocation and a very noble one at that.”

When it comes to educating the youth, Fr. Stephen believed in developing the whole person. This is reflected in the emphasis that he laid not only in the academic arena but also the field of extra-curricular activities. He believed that inculcating, promoting and enhancing values such as compassion, integrity, courage, appreciation, determination, gratitude, loyalty and patience are crucial for the proper upbringing of the younger generation. In 1980, he invited the Prime Minister Hon. R. Premadasa for that year’s prize giving ceremony and in the principal’s address he said “When our young charges leave this emotionally safe and secure world of school with all its disciplines, they must be able to adjust to the wider world in which they must live and work. It is our responsibility to see that they leave the College mentally, spiritually and physically whole, so that they in turn may assume the roles they will be called upon to fulfill in the future”, demonstrating his belief in the advocacy of values.

He identified sports activities as a healthy medium to instill discipline and an acceptable value system and did his utmost in promoting, encouraging and popularising all types of sports in the school. With his foresight and guidance, the school gained new heights in almost all spheres of sports activity. Just to name three great sportsmen who had their grounding in that era are Muttiah Muralidharan – record breaking cricket bowler, Priyantha Ekanayake – a respected past rugby captain of Sri Lanka and president of SLRFU and Udaya Weerakoon – a former national and world inter airline badminton champion.

He did not neglect the expansion of the infra-structure in the school in keeping with the needs of the time. Some of the projects completed during his time were the building of a two-story block of classrooms with the assistance of funds released by the Prime Minister, completion of the indoor sports complex and later a pavilion named after the famous Antonian cricketer Jack Anderson, with the help of the old boys association.

The inspiration that Fr. Stephen Abraham had as Principal within the school community of St. Anthony’s College can be aptly described by John Quincy Adam’s quotation ” May God grant him the eternal reward!

R.N.A. de Silva

The author had his secondary education at St. Anthony’s College, Katugastota, and later served as a member of its staff

rnades@gmail.com

Opinion

Future must be won

Excerpts from the speech of the Chairman of the Communist Party of Sri Lanka, D.E.W. Gunasekera, at the 23rd Convention of the Party

This is not merely a routine gathering. Our annual congress has always been a decisive moment in Sri Lanka’s political history. For 83 years, since the formation of our Party in 1943, we have held 22 conventions. Each one reflected the political turning points of our time. Today, as we assemble for the 23rd Congress, we do so at another historic crossroads – amidst a deepening economic crisis at home and profound transformations in the global order.

Our Historical Trajectory: From Anti-imperialism to the Present

The 4th Party Convention in 1950 was a decisive milestone. It marked Sri Lanka’s conscious turn toward anti-imperialism and clarified that the socialist objective and revolution would be a long-term struggle. By the 1950s, the Left movement in Sri Lanka had already socialized the concept of socialist transformation among the masses. But the Communist Party had to dedicate nearly two decades to building the ideological momentum required for an anti-imperialist revolution.

As a result of that consistent struggle, we were able to influence and contribute to the anti-imperialist objectives achieved between 1956 and 1976. From the founding of the Left movement in 1935 until 1975, our principal struggle was against imperialism – and later against neo-imperialism in its modernised forms,

The 5th Convention in 1955 in Akuressa, Matara, adopted the Idirimaga (“The Way Forward”) preliminary programme — a reform agenda intended to be socialised among the people, raising public consciousness and organising progressive forces.

At the 1975 Convention, we presented the programme Satan Maga (“The Path of Battle”).

The 1978 Convention focused on confronting the emerging neoliberal order that followed the open economy reforms.

The 1991 Convention, following the fall of the Soviet Union, grappled with international developments and the emerging global order. We understand the new balance of forces.

The 20th Convention in 2014, in Ratnapura, addressed the shifting global balance of power and the implications for the Global South, including the emergence of a multipolar world. At that time, contradictions were developing between the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA), government led by Mahinda Rajapaksa, and the people, and we warned of these contradictions and flagged the dangers inherent in the trajectory of governance.

Each convention responded to its historical moment. Today, the 23rd must responded to ours.

Sri Lanka in the Global Anti-imperialist Tradition

Sri Lanka was a founding participant in the Bandung Conference of 1955, a milestone in the anti-colonial solidarity of Asia and Africa. In 1976, Sri Lanka hosted the 5th Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in Colombo, under Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike.

At that time, Fidel Castro emerged as a leading voice within NAM. At the 6th Summit in Havana in 1979, chaired by Castro, a powerful critique was articulated regarding the international economic and social crises confronting newly sovereign nations.

Three central obstacles were identified:

1. The unjust global economic order.

2. The unequal global balance of power,

3. The exploitative global financial architecture.

After 1979, the Non-Aligned Movement gradually weakened in influence. Yet nearly five decades later, those structural realities remain. In fact, they have intensified.

The Changing Global Order: Facts and Realities

Today we are witnessing structural Changes in the world system.

1. The Shift in Economic Gravity

The global economic centre of gravity has shifted toward Asia after centuries of Western dominance. Developing countries collectively represent approximately 85% of the world’s population and roughly 40-45% of global GDP depending on measurement methods.

2. ASEAN and Regional Integration

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), now comprising 10 member states (with Timor-Leste in the accession process), has deepened economic integration. In addition, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – which includes ASEAN plus China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand – is widely recognised as the largest free trade agreement in the world by participating economies.

3. BRICS Expansion

BRICS – originally Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – has expanded. As of 2025, full members include Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Ethiopia and Iran. Additional partner countries are associated through BRICS mechanisms.

Depending on measurement methodology (particularly Purchasing Power Parity), BRICS members together account for approximately 45-46% of global GDP (PPP terms) and roughly 45% of the world’s population. If broader partners are included, demographics coverage increases further. lt is undeniably a major emerging bloc.

4. Regional Blocs Across the Global South

Latin America, Africa, Eurasia and Asia have all consolidated regional trade and political groupings. The Global South is no longer politically fragmented in the way it once was.

5. Alternative Development Banks

Two important institutions have emerged as alternatives to the Bretton Woods system:

• The New Development Bank (NDB) was established by BRICS in 2014.

• The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), operational since 2016, now with over 100 approved members.

These institutions do not yet replace the IMF or World Bank but they represent movement toward diversification.

6. Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO)

The SCO has evolved into a major Eurasian security and political bloc, including China, Russia, India. Pakistan and several Central Asian states.

7. Do-dollarization and Reserve Trends

The US dollar remains dominant foreign exchange reserves at approximately 58%, according to IMF data. This share has declined gradually over two decades. Diversification into other currencies and increased gold holdings indicate slow structural shifts.

8. Global North and Global South

The Global North – broadly the United States, Canada European Union and Japan – accounts for roughly 15% of the world’s population and about 35-40% of global GDP.

The Global South – Latin America, Africa, Asia and parts of Eurasia – contains approximately 85% of humanity and an expanding share of global production.

These shifts create objective conditions for the restructuring of the global financial architecture – but they do not automatically guarantee justice.

Sri Lanka’s Triple Crisis

Sri Lanka’s crisis culminated on 12 April 2022, when the government declared suspension of external debt payments – effectively announcing sovereign default.

Since then, political leadership has changed. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa resigned. President Ranil Wickremesinghe governed during the IMF stabilization period. In September 2024, Anura Kumara Dissanayake of the National People’s Power (NPP) was elected President.

We have had three presidents since the crisis began.

Yet four years later, the structural crisis remains unresolved,

‘The crisis had three dimensions:

1. Fiscal crisis – the Treasury ran out of rupees.

2. Foreign exchange crisis – the Central Bank ran out of dollars.

3. Solvency crisis – excessive domestic and external borrowing rendered repayment impossible.

Despite debt suspension, Sri Lanka’s total debt stock – both domestic and external – remains extremely high relative to GDP, External Debt restructuring provides temporary could reappear around 2027-2028 when grace periods taper.

In the Context of global geopolitical competition in the Indian Ocean region, Sri Lanka’s economic vulnerability becomes even more dangerous,

The Central Task: Economic Sovereignty

Therefore, the 23rd Congress must clearly declare that the struggle for economic sovereignty is the principal task before our nation.

Economic sovereignty means:

• Production economy towards industrialization and manufacturing.

• Food and energy security.

• Democratic control of development policy.

• Fair taxation.

• A foreign policy based on non-alignment and national dignity.

Only a centre-left government, rooted in anti-imperialist and nationalist forces, can lead this struggle.

But unity is required and self-criticism.

All progressive movements must engage in honest reflection. Without such reflection, we risk irrelevance. If we fail to build a broad coalition, if we continue Political fragmentation, the vacuum may be filled by extreme right forces. These forces are already growing globally.

Even governments elected on left-leaning mandates can drift rightward under systemic pressure. Therefore, vigilance and organised mass politics are essential.

Comrades,

History does not move automatically toward justice. It moves through organised struggle.

The 23rd Congress of the Communist Party of Sri Lanka must reaffirm.

• Our commitment to socialism.

• Our dedication to anti-imperialism.

• Our strategic clarity in navigating a multipolar world.

• Our resolve to secure economic sovereignty for Sri Lanka.

Let this Congress become a turning point – not merely in rhetoric, but in organisation and action.

The future will not be given to us.

It must be won.

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoBathiya & Santhush make a strategic bet on Colombo

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoSeeing is believing – the silent scale behind SriLankan’s ground operation

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoBarking up the wrong tree