Midweek Review

EPIC-MEMORY and BRECHT

by Laleen Jayamanne

‘Memory of the World’

UNESCO established the Memory of the World Programme in 1992 to preserve for posterity the audio-visual heritage of humankind, stating that war, social upheaval and lack of resources have accelerated its destruction.

“Significant collections worldwide have suffered a variety of fates. Looting and dispersal, illegal trading, destruction, inadequate housing and funding have all played a part. Much has vanished forever; much is endangered. Happily, missing documentary heritage is sometimes

rediscovered.” UNESCO

UNESCO has also promoted the preservation (through revival), of the vital endangered category of human culture it calls, ‘The Intangible Heritage of Mankind’; the ancient arts of music, dance, theatre and ritual. As temporal arts, they are ephemeral by nature, passed through guru-shishya parampara transmission encoded in bodies through practice, in what used to be called the Third World.

UNESCO has also promoted the preservation (through revival), of the vital endangered category of human culture it calls, ‘The Intangible Heritage of Mankind’; the ancient arts of music, dance, theatre and ritual. As temporal arts, they are ephemeral by nature, passed through guru-shishya parampara transmission encoded in bodies through practice, in what used to be called the Third World.

Thanks to the availability of digital technological tools of preservation, exhibition and connectivity, the work of these visionary programmes has been considerably enhanced. Now, the fragile celluloid film, which was once the medium of preservation of artefacts, has itself been saved, restored and preserved digitally. Apart from this kind of essential programme of preservation, the very idea of attributing memory to the ‘world’, in the UNESCO formulation, is fascinating to speculate on because we usually think of memory as an inalienable human organic faculty of the mind without which we would live in a perpetual state of amnesia, in a timeless and depleted present. It seems to me that ‘memory of the world’ as an idea can also be imagined as something more than historical memory, which by definition is the written record, usually organised chronologically. ‘The world’ can now also suggest not only the human but also the earth itself and all that it sustains, plants and animals and even microbes and fossils and minerals and the cosmos, too. This is the zone that some artists have begun to explore within a ‘deep-ecological’ consciousness of what is known as the Anthropocene – the epoch of man-made ecological devastation.

‘Epic-Memory’

Walter Benjamin, the German theorist of culture, in his essay, The Story Teller, described another kind of memory, created by humans over millennia, which he called ‘epic memory.’ He invites us to imagine how to think about an idea of memory that’s more ample than our personal memory, by offering a dazzling image of ‘epic memory.’

“One must imagine the transformation of epic forms occurring in rhythms comparable to those of the change that has come over the earth’s surface in the course of thousands of centuries. Hardly any other forms of human communications have taken shape more slowly, been lost more slowly.

Memory is the epic faculty par excellence.

Memory creates the chain of tradition which passes a happening on from generation to generation.”

What Benjamin calls the ‘chain of tradition’ has been severed or partially lost in societies subject to colonisation and the forces of modernity have also destroyed many traditions. So we are looking for ways in which an expansive mode of remembering might be generated by artists through creative work, especially in the post-war situation of Sri Lanka where experiences of loss and trauma are widespread and some of their causes left unaddressed, forgotten, repressed, for many reasons. And now especially, with Sri Lanka in a state of profound crisis open to new possibilities of collective life free of ethnic nationalism and violence, an idea of epic memory might be of some use. It is the case that we don’t have ancient epics like India’s, Silappatikaram, Mahabharata and the Ramayana or the Greek ones, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Yet a modern idea of epic memory can perhaps still be formulated with what we do have.

The epic form was originally an oral form, which required from the bards a prodigious memory, trained through repeated recitation, which is why the muse of the epic form was called Mnemosyne, meaning epic memory in Greek. The written form of the epic came into being much later in history, based on the much older collective oral poetry of legends and myths of ‘the people’ handed down orally. Both in the UNESCO idea of ‘memory of the world’ and Benjamin’s definition of ‘epic memory,’ what is clear is that memory is a collective creation, taking shape over vast epochs. According to Greek myth, Mnemosyne, is the mother of the nine muses, and the word mouseion in Greek (from which the word museum is derived) means the dwelling place of the muses, who are the inspiration for the different art forms. This is a rich vital aesthetic image of the museum which is worth thinking about.

Then, one might be tempted to think that this is the same as the idea of ‘civilization’, which is the sum total of a culture’s pre-history and history as expressed in artefacts and written record. Usually this is indeed how nation states constitute themselves and give themselves an identity formulated on ethnicity, language, religion, custom, myths, etc. This is dangerous territory because states have deployed their myths to justify authoritarian and racist policies to divide and rule multi-ethnic, multi-religious, multi-linguistic societies such as Lanka. The Rajapaksa regime mobilised the Mahavansa narrative of Sinhala-Buddhist hegemony of Lanka to secure its own rule and some artists joined in with the mythic-epic genre films and shows. But I think the UNESCO idea is counter-hegemonic because it’s not created by a centralising state. Its memories may not fit easily into a master narrative of mythic inevitability. There is an element of chance and the possibility of ‘minor narratives’ emerging, which can’t be totalised into primordial myths.

Brecht’s Theory of Epic Theatre

To create a clearer picture of how to craft an idea of memory with great amplitude and rich potential, we can start with a modern example, the work of Bertolt Brecht, which Lankans have been quite familiar with (since the mid 1960’s), in all three languages. He famously created an ‘epic theatre’ and a theory of modern epic practice, as opposed to the traditional ‘dramatic theatre’. He called traditional dramatic theatre Aristotelian because it followed the basic structures analysed by the Greek philosopher in his Poetics. Walter Benjamin wrote several essays defending Brecht’s idea of epic theatre because what Brecht did was something quite unusual within the history of European theatre at the time. Instead of following the 1920s avant-garde German Expressionist theatre or French Surrealist theatre or constructivist Soviet practice, he looked to classical Asiatic theatrical forms such as Peking opera and its conventions of staging and highly formalised abstract forms of acting, to create a modern epic practice. For some artists of the left, Brecht’s theory appeared to be a strange move, looking to traditional Asian practice of the deep feudal past – not at all modern. Benjamin showed how Brecht’s modern epic form was suited to their time of the rise of fascism in Germany and its appeal to irrational emotions and ideas of racial purity and superiority. According to Aristotle the epic form contains three genres in one. That is, the lyric or ‘first person’ expression of subjective feeling as in love poetry, the dramatic as in actions and reactions organised in dialogue, in ‘second person’ and narration, which is the power to tell a story or narrate in ‘third person’. Therefore the ample epic mode can combine all three genres with ease, which means that it has the power to shift focus from one to the other, in complex combinations.

The traditional idea of ‘epic memory’ itself has an act of performance built into it through what is sung and is not something private and personal but consists of mythic stories, legends common to a people. But there is a crucial distinction Brecht and Benjamin made here between myth, on the one hand, and the epic form, on the other. The epic as a genre is a much later historical development from myth and though it does deploy myth, it does so on its own terms. Because, historically speaking, the epic is a later human achievement than myth, it also has had the rational power to comment on the myths it uses. That is to say, the epic form, with its many flexible techniques, has the power to create a sense of distance from the mythic universe of the ancients, which appears irrational and fated.

This idea of a historical ‘distance’ of the epic form (from the original myths), was taken up by Brecht and made into a method of constructing his epic drama. He called it, using a long German compound word, ‘verfremdungseffect’, variously translated as ‘distanciation’ or ‘Alienation-effect’ or ‘de-familiarisation’ or ‘making-strange’. Fine scholarship is available on this idea, my favourite was developed by Eugenio Barba and his Odin Theatret in Denmark. To create a dramatic situation which can immediately be ‘frozen’ and turned into a scene which is narrated and commented on, is one of the well-known ways in which Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle was performed in Colombo, in the 1965 by Ernest Macintyre’s ‘Stage and Set’ production. The tender scene of a lyrical song sung by Grusha to her adopted infant son, can swiftly change to a bawdy commentary by the chorus. Sudden changes of point of view, mood and tone, are calibrated to give the spectator a chance to perceive a situation from more than one angle. It’s a way to introduce the exercise of reason into the spectacle of theatre, according to Brecht, to break its spell even as it is deployed. Brecht was here influenced by Eisenstein’s theory of montage, which he introduced into theatre. Eisenstein’s theory of montage created a clash between one shot and another, so as to produce a new idea in the mind of the spectator. So the continuously flowing conventional dramatic action could be interrupted, fragmented and anything-what-ever from ‘the memory of the world’ could be inserted to break the flow. So it’s the introduction of a radical film technique, montage, into theatre to make the mind constantly alert and instantly beguiled and then relaxed by the commentary of the chorus. These disjunctions can be very subtle or very direct depending on the skill of both actor and director.

Professor Saumya Liyanage’s recent article, on the play ‘Sanga Veda Guru Govi Kamkaru’, clearly indicated that the brilliant young playwright-director Chamila Priyanka had created an epic mode of theatre, which the judges of the drama competition failed to understand, (The Island, 11/5). Liyanage said that there is a to and fro movement between empathy and distance in the way the play was constructed and directed. The current Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe referred to Brecht in parliament, comparing his current task (to save Lanka), to that of the selfless Grusha’s action of saving the baby, treading on the rickety bridge. Whether he wanted empathy or analytical distance by offering this parable from the Caucasian Chalk Circle we don’t know, but he could assume that Lankans at large would know the reference. But we also know the play well enough to see what a thoughtless comparison it was.

The Artists’ Protest March

I saw a Brechtian epic mode in full flight in the artists’ protest march (#GotaGoGama), the other day on the streets of Colombo, which converged on Gall Face. Actors wearing handmade cardboard masks of the various yakas and the sunniyas were doing wild dancing moves using these marvellous creatures of the folk imagination of Lanka to exorcise the political demons sucking the people’s life-blood. These performers were such a refreshing counter to the expensive kitsch fascist-mythic-nationalist spectacles and films made under the Rajapaksa regime. And to see and hear a group of women walking rhythmically and playing the heavy drums slung across their bodies strung from their necks or tied at the waist, was a powerful moment for me, as I never imagined that Lankan women would be allowed to play these ritual drums belonging to a male tradition of such vitality. Traditionally, women only played raban pada! While the documentary camera excitedly cut between many performances very fast, I got the sense of an epic vision being performed as street theatre. Gamini Hattotuwegama’s pioneering street theatre work of the 70’s and 80’s seems to have taken on an unimaginable mass form, matured, diversified, loosening up and airing so many different stratified and compacted layers of the blood-soaked earth, of this famed ‘island of Dhamma’, Sri Lanka.

Perhaps artists can generate some ideas from these two modes of imagining memory (‘memory of the world’ and Brecht’s epic mode), which are quite distinct from personal memory. Artists working on traumatic experiences of the civil war and the formidable state ideologies that led to and orchestrated it, may find it useful to try to mobilise an ample epic mode of perception. I think so because it has this flexible montage structure, not tied to a strict linear chronology. ‘Montage’ is a term taken from engineering, of fitting different pieces of machinery together, so it contains the idea of assembling something with different components, stuff, to make something happen. While one might work on oneself and one’s sense of loss and a host of other urgent feelings that resist linguistic expression, one can also create certain disjunctions, breaks, (distanciation, make-strange the familiar), through an epic mode of composition. The need to repeatedly go back to the traumatic moment is often limitless, with no end in sight. Each repetition yields less as it becomes routine with no exit. Whereas, epic vision-memory, understood in a Brechtian way, is centrifugal not centripetal, it ripples out. It is not centred on man and nor is its vision cut to the measure of MAN. It is non-anthropocentric and non-anthropomorphic. Epic vision-memory helps us to see and feel and understand that we are part of something vaster and also much finer and subtle than ourselves. Epic vision gives us antennae like insects have. Tantric Buddhist idea of a ‘subtle body’ (Sukshama Dehaya) might be a line of investigation for those attracted to the rich visual traditions of Mahayana Buddhism which include vast scroll paintings which visually activate ‘nadi’ or a nervous system that connects many life forms too.

Brecht’s epic vision, in not giving ‘happy endings’ or resolving all the dramatic conflicts, leave us with an ability to discuss alternatives, as in say The Good Woman of Szechwan (Hita Honda Ammandi). I think the famous Chennai bonze statues of poets, (including a female one), and scholars (including an English scholar-missionary), and the epic heroine of Silappatikāram, Kannagi, lining the ocean front of the Marina really is a marvellous epic configuration that could also be understood in the Brechtian modern sense of the epic as well. They are positioned against the background of the ocean and address the people of Tamil Nadu evoking epic memory. The idea of debate so dear to Brecht also was staged when the Kannagi statue built by the Karunanidi’s DMK government was removed from her pedestal by Jaylalitha as Chief Minister, inaugurating a statue ‘battle’ and then returned from a museum, back again to her pedestal, with a change of government. There appears to be a sense of humour too in these serious political moves and counter moves, a marvellous sense of epic performance. This kind of jostling, argumentative, magnificent vision evoked by these bronze statues of Tamil Nadu is surely a modern mode of epic memory conjoined with the ocean, the sand and the sky – a memory of the world for sure.

Epic form is not the same as mythic form. The epic is Janus-faced (has two faces) facing two opposed directions. One face is turned toward myth and the other faces history. And situated in between the two, it has ample space-time to play and shuttle between the two modes of knowledge by making sure that history itself is not allowed to turn into myth.

And Laughter?

I saw on YouTube a well-known Sinhala actor perform a strange oration of excessive praise, a Rajapaksha varnanawa, invoking the glory days of Dutugamunu. What struck me was how much the brothers Mahinda and Gotabhaya laughed when they were praised in more and more exaggerated ways (drawing on the heroic parallels), by the actor who appeared to be carried away by his own brilliance at flattery and histrionic performance. I couldn’t help but think that the two brothers were looking at each other in a certain way and laughing, as much as to say, ‘does he really believe this stuff he’s spouting, what an idiot!’ They appeared to know that these were stupid but useful myths that they had themselves mobilised as history for their gain, but the true believers and the fools were the people themselves. This is just my reading of laughter of the two authoritarian brothers. Laughter is a tricky involuntary human impulse hard to control and pin down rationally. But one hopes that the last laugh will not be theirs’ to enjoy.

Midweek Review

A look back at now mostly forgotten Eelam war in the aftermath of Kashmir massacre

In the aftermath of the Pahalgam massacre, Pakistan offered to cooperate in what it called a neutral investigation. But India never regretted the

catastrophic results of its intervention in Sri Lanka that led to the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi in May 1991, over a year after India pulled out its Army

from NE, Sri Lanka

In a telephone call to Indian Premier Narendra Modi, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake condemned the massacre of 26 civilians – 25 Indians and one Nepali – at Pahalgam, in the Indian controlled Kashmir, on April 22.

President Dissanayake expressed his condolences and reaffirmed, what the President’s Media Division (PMD) called, Sri Lanka’s unwavering solidarity and brotherhood with the people of India.

Having described the massacre as a terrorist attack, New Delhi found fault with Pakistan for the incident. Pakistan was accused of backing a previously unknown group, identified as Kashmir Resistance.

The Indian media have quoted Indian security agencies as having said that Kashmir Resistance is a front for Pakistan-based terrorist groups, Lashkar-e-Taiba and Hizbul Mujahideen fighting Indian rule in Kashmir. Pakistan says it only provides moral and diplomatic support.

Pakistan has denied its involvement in the Pahalgam attack. A section of the Indian media, and some experts, have compared the Pahalgam attack with the coordinated raids carried out by Hamas on southern Israel, in early October 2023.

President Dissanayake called Premier Modi on the afternoon of April 25, three days after the Pahalgam attack. The PMD quoted Dissanayake as having reiterated Sri Lanka’s firm stance against terrorism in all its forms, regardless of where it occurred in the world, in a 15-minute call.

Modi cut short his visit to Saudi Arabia as India took a series of measures against Pakistan. Indian actions included suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) governing water sharing of six rivers in the Indus basin between the two countries. The agreement that had been finalised way back in 1960 survived three major wars in 1965, 1971 and 1999.

One-time Pentagon official Michael Rubin, having likened the Pahalgam attack to a targeted strike on civilians, has urged India to adopt an Israel-style retaliation, targeting Pakistan, but not realising that both are nuclear armed.

Soon after the Hamas raid some interested parties compared Sri Lanka’s war against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), and the ongoing Israel war on Gaza.

The latest incident in Indian-controlled Kashmir, and Gaza genocide, cannot be compared under any circumstances. Therefore, suggestions that India adopt Israel-style retaliation against Pakistan do not hold water. Also, Sri Lanka’s war against the LTTE that was brought to a successful conclusion in May 2009 cannot be compared with the conflict Israel is involved in.

Sri Lanka can easily relate to the victims of the Pahalgam attack as a victim of separatist terrorism that bled the country for nearly 30 years. India, however, never bothered to express regret over causing terrorism here.

Indian-sponsored terror projects brought Sri Lanka to its knees before President JRJ made an attempt to eradicate the LTTE in May-June 1987. JRJ resorted to ‘Operation Liberation’ after Indian mediated talks failed to end the conflict. Having forced Sri Lanka to call off the largest-ever ground offensive undertaken at that time with the hope of routing the LTTE in Vadamarachchi, the home turf of Velupillai Prabhakaran, followed by India deploying its Mi 17s on July 24, 1987, to rescue the Tiger Supremo, his wife, two children and several of his close associates – just five days before the signing of the so-called Indo-Lanka peace accord, virtually at Indian gun point.

First phase of Eelam war

During the onset of the conflict here, the LTTE routinely carried out raids on predominantly Sinhala villages where civilians were butchered. That had been part of its strategy approved by ‘controllers’ based across the Palk Straits. That had been a volatile period in the run-up to the July 29, 1987, accord. Although India established half a dozen terrorist groups here, the LTTE had been unquestionably the most violent and the dominant group. To New Delhi’s humiliation all such groups supported by it were wiped out by the marauding Tigers.

Those who compared the LTTE with Hamas, or any other group, conveniently forget that the Sri Lankan group caused significant losses to its creator. India lost over 1,300 officers and men, while nearly 3,000 others suffered injuries during the Indian deployment here (July 1987-March 1990).

The world turned a blind eye to what was going on in Sri Lanka in the ’80s. The war launched by India in the early ’80s against Sri Lanka lasted till the signing of the peace accord. That can be broadly identified as phase one of the conflict (1983 July – 1987 July). That first phase can be safely described as an Indian proxy war aimed at creating an environment conducive for the deployment of the Indian Army.

Having compelled President JRJ to accept deployment of the Indian Army in the northern and eastern regions in terms of the “peace accord”, New Delhi sought to consolidate its hold here by disarming all groups, except the one it had handpicked to run the North-East Provincial Council. The Indian Army oversaw the first Provincial Council election held on Nov. 19, 1988, to elect members to the NE council. The whole exercise was meant to ensure the installation of the Varatharaja Perumal led-EPRLF (Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Forint) administration therein.

The second phase (1987 July – 1990 March) saw a war between the Indian Army and the LTTE. During this period, the Indian Army supervised two national elections – presidential on Dec. 19, 1988, and parliamentary on Feb. 15, 1989, that were won by Ranasinghe Premadasa and the UNP.

During that period, the UNP battled the JVP terror campaign and the South bled. The JVP that resorted to unbridled violence against the Indo-Lanka accord, at that time, has ended-up signing several agreements, including one on defence cooperation, recently, and the country is yet to get details of these secret agreements.

Raid on the Maldives

The second phase of the Eelam conflict ended when India pulled out its Army from NE Sri Lanka in March 1990. The sea-borne raid that had been carried out by Indian-trained PLOTE (People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam) targeting Maldivian President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, in Nov. 1988, is perhaps a significant development during the second phase of the conflict, though it was never examined in the right context.

No one – not even the Maldives – found fault with India for exporting terrorism to the island nation. India received accolades for swift air borne intervention to neutralise the PLOTE group. The Indian Navy sank a vessel commandeered by a section of the PLOTE raiders in a bid to escape back to Sri Lanka. The truth is that PLOTE, that had been trained by India to destabilise Sri Lanka, ended-up taking up a lucrative private assignment to overthrow President Gayoom’s administration.

India never regretted the Maldivian incident. It would be pertinent to mention that two boat loads of PLOTE cadres had quietly left Sri Lanka at a time the Indian Navy was responsible for monitoring in and out sea movements.

In the aftermath of the Pahalgam massacre, Pakistan offered to cooperate in what it called a neutral investigation. But India never regretted the catastrophic results of its intervention in Sri Lanka that led to the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi in May 1991, over a year after India pulled out its Army from NE, Sri Lanka.

Resumption of hostilities by the LTTE in June 1990 can be considered as the beginning of the third phase of the conflict. Having battled the Indian Army and gained valuable battle experience, the LTTE, following a 14-month honeymoon with President Ranasinghe Premadasa, resumed hostilities. Within weeks the LTTE gained the upper hand in the northern theatre of operations.

In spite of India banning the LTTE, after the May 1991 assassination of Gandhi, the group continued to grow with the funds pouring in from the West over the years. Regardless of losing Jaffna in 1995, the LTTE consolidated its position, both in the Vanni and the East, to such an extent their victory seemed inevitable.

But resolute political leadership given by Mahinda Rajapaksa ensured that Sri Lanka turned the tables on the LTTE within weeks after the LTTE appeared to be making significant progress at the beginning. Within two years and 10 months (2006 August – 2009 May) the armed forces brought the LTTE to its knees, and the rest is history. As we have said in our earlier columns that victory was soon soured. Spearheaded by Sarath Fonseka, the type of General that a country gets in about once in a thousand years, ended in enmity within, for the simple reason this super hero wanted to collect all the trophies won by many braves.

Post-war developments

Sri Lanka’s war has been mentioned on many occasions in relation to various conflicts/situations. We have observed many distorted/inaccurate attempts to compare Sri Lanka’s war against LTTE with other conflicts/situations.

Unparalleled Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israel, triggered a spate of comments on Sri Lanka’s war against the LTTE. Respected expert on terrorism experienced in Sri Lanka, M.R. Narayan Swamy, discussed the similarities of Sri Lanka’s conflict and the ongoing Israel-Gaza war. New Delhi-based Swamy, who had served UNI and AFP during his decades’ long career, discussed the issues at hand while acknowledging no two situations were absolutely comparable. Swamy currently serves as the Executive Director of IANS (Indo-Asian News Service).

‘How’s Hamas’ attack similar to that of LTTE?’ and ‘Hamas’ offensive on Israel may bring it closer to LTTE’s fate,’ dealt with the issues involved. Let me reproduce Swamy’s comment: “Oct. 7 could be a turning point for Hamas similar to what happened to the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in Sri Lanka in 2006. Let me explain. Similar to Hamas, the LTTE grew significantly over time eventually gaining control of a significant portion of Sri Lanka’s land and coast. The LTTE was even more formidable than Hamas. It had a strong army, growing air force and a deadly naval presence. Unlike Hamas, the LTTE successfully assassinated high ranking political figures in Sri Lanka and India. Notably, the LTTE achieved this without direct support from any country while Hamas received military and financial backing from Iran and some other states. The LTTE became too sure of their victories overtime. They thought they could never be beaten and that starting a war would always make them stronger. But in 2006 when they began Eelam War 1V their leader Velupillai Prabhakaran couldn’t have foreseen that within three years he and his prominent group would be defeated. Prabhakaran believed gathering tens of thousands of Tamils during the last stages of war would protect them and Sri Lanka wouldn’t unleash missiles and rockets. Colombo proved him wrong. They were hit. By asking the people not to flee Gaza, despite Israeli warnings, Hamas is taking a similar line. Punishing all Palestinians for Hamas’ actions is unjust, just like punishing all Tamils for LTTE’s actions was wrong. The LTTE claimed to fight for Tamils without consulting them and Hamas claimed to represent Palestinians without seeking the approval for the Oct.7 strike. Well, two situations are not absolutely comparable. We can be clear that Hamas is facing a situation similar to what the LTTE faced, shortly before its end. Will Hamas meet a similar fate as the LTTE? Only time will answer that question.” The above was said soon after the Oct. 2023 Hamas attack.

Swamy quite conveniently refrained from mentioning India’s direct role in setting up one of the deadliest terror projects in the world here in the ’80s.

Former Editor of The Hindu, Malini Parthasarathy, who also had served as Chairperson of The Hindu Group, released a list of politicians assassinated by the LTTE, as she hit back hard at those who raged against the comparison of the Hamas to the LTTE. The list included two Jaffna District MPs, Arumugam Murugesu Alalasundaram and Visvanathan Dharmalingam, assassinated in early Sept. 1985. Slain Visvanathan Dharmalingam’s son, Dharmalingam Siddharthan, who represents the Vanni electoral district on the Illankai Thamil Arasu Kadchi (ITAK), is on record as having said that the two MPs were abducted and killed by TELO (Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation.) gunmen. The list posted by Parthasarathy included PLOTE leader Uma Maheswaran, assassinated in Colombo in July 1989. The LTTE hadn’t been involved in that killing either. Maheswaran is believed to have been killed by his onetime associates, perhaps over the abortive PLOTE raid on the Maldives in Nov, 1988. India never bothered at least to acknowledge that the Maldives raid was carried out by men trained by India to destabilise Sri Lanka. There is no doubt that Maheswasran’s killers, too, were known to the Indian intelligence at that time.

Before rushing into conclusions regarding Hamas and the LTTE, perhaps a proper examination of the circumstances they emerged is necessary. The two situations – fourth phase of the Eelam conflict and the latest Hamas strike on Israel and the devastating counter attack – cannot be compared under any circumstances. Efforts to compare the two issues is more like comparing apples and oranges, though mutually Tamils and Sinhalese have so many commonalities having intermingled throughout history like the Arabs and Jews.

It is no doubt Jews are a people that suffered persecution throughout known history under Assyrians, Babylonians to Romans and so forth. Such persecution includes expulsion of Jews from England in 1290 and from Spain 1492. So what Hitler and the Germans did was to take the historic process to another extreme.

Yet to blame the Palestinians and treat them like animals and to simply butcher them for the latest uprising by Hamas for all the humiliations and suffering they have been going through non-stop since Naqba in1948, from the time of the creation of Israel is to allow the creators of the problem, including the UK, the USA and United Nations to wash all their sins on the true other victims of this conflict, the Palestinians.

It would be pertinent to mention that Israel, in spite of having one of the world’s best fighting armed forces with 100 percent backing from the West, cannot totally eradicate Hamas the way Sri Lanka dealt with the LTTE. Mind you we did not drop 2000 pound bombs supplied by the US on hapless Tamil civilians to commit genocide as is happening in Palestine in the hands of the Israelis.

The circumstances under which the LTTE launched a large-scale offensive in Aug. 2006 and its objectives had been very much different from that of Hamas. The LTTE really believed that it could have defeated the Sri Lankan military in the North by cutting off the sea supply route from Trincomalee to Kankesanthurai and simultaneously overrunning the Kilali-Muhamalai-Nagarkovil forward defence line (FDL). The total collapse of the FDL could have allowed the LTTE to eradicate isolated fighting formations trapped north of the FDL. But, in the case of the Gaza war, the Hamas strike was meant to provoke Israel to unleash a massive unbridled counter attack that caused maximum losses on the civilians. As Hamas expected the Israeli counter attack has triggered massive protests in the West against their leaders. They have been accused of encouraging violence against Palestine. Saudi Arabia, Jordan and other US allies are under heavy pressure from Muslims and other horrified communities’ world over to take a stand against the US.

But in spite of growing protests, Israel has sustained the offensive action not only against Gaza but Lebanon, Yemen and Iran.

Instead of being grateful to those who risked their lives to bring the LTTE terror to an end, various interested parties are still on an agenda to harm the armed forces reputation.

The treacherous Yahapalana government went to the extent of sponsoring an accountability resolution against its own armed forces at the Geneva-based UNHRC in Oct. 2015. That was the level of their treachery.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Midweek Review

The Broken Promise of the Lankan Cinema:

Asoka & Swarna’s Thrilling-Melodrama – Part III

“‘Dr. Ranee Sridharan,’ you say. ‘Nice to see you again.’

The woman in the white sari places a thumb in her ledger book, adjusts her spectacles and smiles up at you. ‘You may call me Ranee. Helping you is what I am assigned to do,’ she says. ‘You have seven moons. And you have already waisted one.’”

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida

by Shehan Karunatilaka (London: Sort of Books, 2022. p84)

(Continued from yesterday)

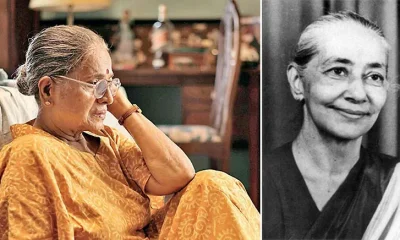

Rukmani’s Stardom & Acting Opportunity

Rukmani Devi is still remembered for her incomparable singing voice and her studio photograph by Ralex Ranasinghe with its hint of Film Noir mystery and seduction, and for the role of Blanch Dubois she played in Dhamma Jagoda’s Vesmuhunu, an adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. This is a role she shared on alternate nights with Irangani Serasinghe in the late 60s or early 70s. (See my Island Essays, 2024, p114) She was immensely happy to be able to act in a modern western classic directed by a visionary theatre director like Dhamma Jagoda and it was to his credit that he chose to give her that role when all acting roles had dried up for her. I observed those rehearsals held at Harrold Peiris’ open garage.

I, too, am happy that Swarna has had a chance to perform again in her 70s. The question is, how exactly has she used that very rare opportunity to act in a film that has doubled its production cost within two months, and now showing in private screenings in multiplexes in Australia with English subtitles, with ambitions to be shown on Netflix and Amazon Prime. These outlets also now fund films and make challenging mini-series. Rani has clearly been produced and marketed with this global distribution in mind. How does this important fact affect Swarna’s style of acting and the aesthetics of Asoka’s script, are the questions I wish to explore in the final section of this piece.

A Sensational-Thrilling Political & Family Melodrama

‘Melodrama’ is a popular genre with a history that goes back to 19th century theatre in the west and with the advent of film, Hollywood took it up as it offered a key set of thrilling devices known as ‘Attractions’, for structuring and developing a popular genre cinema. The word ‘Melodrama’ is a compound of the Greek word for music ‘melos’ and drama as an action, with the connotation of a highly orchestrated set of actions. The orchestration (not only with sound but also the speed and rhythm of editing, dramatic expressive lighting, ‘histrionic’ acting, etc.,) always reaches toward thrilling climaxes and at times exaggerated display of emotions. The plots are sensational, propelled by coincidences and written to reach climaxes and dramatic reversals of fortune, and sudden revelations. Hollywood was famous for its happy endings with resolution of the dramatised conflicts, while Hindi melodramas and Lankan copies often ended sadly.

In the history of cinema there are highly sophisticated melodramas within Hollywood, classical Hindi cinema and also in European art cinema. Rainer Werner Fassbinder was one of the German directors who developed a modern ‘Brechtian-Melodrama’ of extraordinary political and aesthetic power in the 70s. And of course, there are very poorly conceived melodramas too like many of the Sinhala films which were copies of Indian prototypes. Melodramatic devices inflect the different genres of Hollywood, for example the Gangster Film, the Western and created durable genre types in character, e.g. the Gangster, the Lonesome Cowboy and Indians; all national stereotypes, one embodying the underbelly of American capitalism, an anti-hero and the other the American hero actualising The American Dream. ‘The Indian,’ merely the collateral damage of this phantasy!

When the stories were centred on women the genre classification was ‘Women’s Melodrama’ as it dealt with interpersonal relations, conflicts, and sadness centred on the home primarily. Feminist film theory has developed a vast archive of scholarship on the melodramatic genre, cross-culturally, with a special focus on Hollywood and Hindi cinema decades prior to the formation we now call Bollywood, made with transnational capital and global reach. It was assumed that the audience for the family melodramas was female and that as women, we enjoy crying at the cinema, hence the condescending name ‘The Weepies’. I cut my scholarly/critical teeth studying these much-maligned melodramatic films for my doctorate, which I had enjoyed while growing up in a long-ago Ceylon.

Asoka’s Melodramatic Turn

Asoka in Alborada, but more so in Rani has made melodramatic films with his own ‘self-expressive’ variations on the structure, with an ‘Art Cinema’ gloss. He has said that Rani is more like Alborada and unlike his previous films made during the civil war. This is quite obvious. Though the advertising tag line for Alborada claimed it as a ‘Poetic film that Neruda never made’ it was a straightforward narrative film. I have argued in a long essay (‘Psycho-Sexual Violence in the Sinhala Cinema: Parasathumal & Alborada’, in Lamentation of the Dawn, ed. S. Chandrajeewa, 2022, also tr. into Sinhala, 2023), that the staging of the rape of the nameless, silent, Dalit woman is conceived in a melodramatic manner playing it for both critique and exciting thrills. This is a case of both having his cake and eating it.

Swarna’s Melodramatic Turn

The film appears to be constructed, plotted melodramatically, to demonstrate Swarna’s ability to perform dramatic scenes of high excitement in areas of taboo, the opportunity for which is unavailable to a Sinhala actress, in a Sinhala film, playing the role of a Sinhala Buddhist mother, who has lost her son to an act of terror unleashed by the Sinhala-Buddhist State terror and Sinhala-Buddhist JVP.

In short, Swarna has been given the opportunity to demonstrate how well she can perform a range of Melodramatic emotions that go from say A to, say D. She has been given the chance to move smoothly from English to Sinhala as the middle classes do; use the two most common American expletives which are part of the American vernacular; drink for pleasure but also to the point of getting drunk; offer alcohol to her baffled domestic worker; coax her son and friends to drink; dance with them in an inebriated state; pour alcohol, whisky, not arrack, like one would pour water from a bottle; chain smoke furiously; dash a full mug of tea on the floor in a rage; crumple on the floor sobbing uncontrollably; shout at her loyal aid Karu; speak with sarcasm to a police officer insisting that she is ‘Dr Manorani …’ not ‘Miss or Mrs’, like feminists did back in the day; chat intimately with a minister of the government; look angrily and scowl at President Premadasa when he comes to the funeral house to condole with her; stage Richard’s funeral in a Catholic church with a stain glass window of the Pieta; to quote a well-known Psalm of David from the Bible, ‘Oh Absalom my son, Oh my son!’; etc.

Rani is Swarna’s chance to show that she can perform in ways that no Sinhala script has allowed a Sinhala actor to do up to now, that is, behave like the Sinhala cinema’s fantasy of how the upper-class Anglophone Lankan women behave. In short not unlike, but much worse, than the ‘bad girls’ in the Sinhala melodramatic genre cinema who always ended up in a Night Club, the locus of licentiousness that tempt them. I am thinking of Pitisara Kella from the 50s and a host of other films. Sinhala cinema simply cannot convincingly present the upper-class English-speaking milieu, with any nuance and conviction, it just feels very stilted, poorly acted therefore. Saying this is not class snobbery on my part. Even Lester James Peries from this very upper class and a Roman Catholic, in Delowak Atara couldn’t do it with Irangani Serasinghe and others. The dialogue meant to be serious or just plain normal sounded stilted and even funny. But when Lester did the Walauwa as in Nidhahanaya, it was brilliant, one of our classics. Brecht it was who said (on the eve of WW2, creating a Modern Epic mode of theatre in exile, that it’s not easy to make drama about current events. It’s much easier to look back with nostalgia at a genteel aristocratic Sinhala past for sure.

In taking the opportunity to explore kinetic and emotional behaviour considered to be taboo for a Sinhala woman, a fantasy Tamil woman has been fabricated. The plot of Rani is constructed by Asoka to provide Swarna the opportunity to indulge in these very taboos. In short, the fictional Tamil Rani offers Swarna an acting opportunity to improve her career prospects in the future. In so doing she has weakened her ability, I fear, to evolve as an actress.

A Domestic Melodrama: The House Suspended in a Void

If Swarna so desired, if the script ‘allowed her’ to, she could have tried to develop a quieter, more restrained and therefore a more powerful Rani. A friend of the family, when asked, said that, “The most striking feature of Manorani was her quiet, confident dignity, before and after Richard.” To testify to such a person, Asoka and Swarna could have asked the obvious question, did she have any close friendships formed as undergraduates, who supported her during this tragedy, as there certainly were cherished friends who shared her grief. After all, she was among the elite first generations of Ceylonese women to enter University in the 1940, to medical school at that!

Asoka and Swarna have entrapped their Rani in a vacuum of a house, friendless, with a little cross on Richard’s wall to signify religion. A lot of effort has gone into the set decoration and art direction of the house, as in Alborada, to stage a fantasy/phantasy melodramatic scenario. There is no real sensory, empathetic feel and understanding of the ethos (character), of this urbane Anglophone Ceylonese-Lankan mother and son, hence the fictionalised scenarios feel synthetic, cosmetic in the best traditions of the Sinhala genre cinema’s representation of the ‘excessive and even grotesque upper-class’. Except, here the Realism of the mise-en-scene (the old-world airy house and furniture and composition of the visual components) makes claims to a realist authenticity. A little modest research would have shown that Manorani and Richard moved from one rented apartment to another in the last few years of his life and when he was abducted, lived on the upper-floor of a house, in a housing estate in Rajagiriya. Asoka said in an interview that it wasn’t possible to find in Colombo the kind of old house they required for Rani. So, they went out of town to find the ideal house suited to stage their phantasy.

I suspect that it was Swarna who called shots this time, not Asoka who was recovering from a serious illness. He said that she brought the project to him and the producer and that he had no idea of making a film on Manorani, but added that he wrote the script within 3 months. I suspect that this Rani, (this out of control, angry, scowling, bad tempered, lamenting, hysterical Rani, reaching for the alcohol and cigarettes to assuage her grief, performing one sensational, thrilling melodramatic turn after another), was Swarna’s conception, her version of Manorani that she has nursed for 28 long years. Had she resisted this temptation to display her high-intensity acting-out skills yet again, she might just have been able to tap unsuspected resources within herself which she may still have as a serious actress. Its these latent affective depths that Rukmani Devi undoubtedly tapped when she was invited to play the drunken and lost Blanche Dubois, in A Streetcar Named Desire in Sinhala, as a desperate, drunken, aristocratic lady, in Dhamma Jagoda’s Vesmuhunu (1971?).

Jagoda / Irangani

It is reported that before going on stage, Rukmani Devi went on her hands and knees to pay her respects to Dhamma, not as feudal act of deference but to acknowledge his Shilpiya Nuwana, craft knowledge/intelligence’, as one very perceptive Sinhala critic put it. That gesture of Vandeema was foreign to the Tamil Christian Rukmani Devi, but nevertheless it shows her sense of immense gratitude to Dhamma for having taken her into a zone of expression (a dangerous territory emotionally for dedicated vulnerable actors), that she had never experienced before, so late in her life. But ‘late’ is relative to gender, then she was only in her 50s!

Challenge is what serious actors yearn for, strange beings who may suggest to us intensities that sustain and amplify life, all life. Swarna might usefully think about Rukmani Devi, her life and her star persona as a Tamil star in countless sarala Sinhala films, in whose shadow and echo every single Sinhala actress has entered the limelight, Swarna more so now than any other!

As for Asoka, he needs to rest and take care of himself before he commits himself to this recent track of films which are yielding less and less with each of the two films done back to back. His body of work is too important to trash it with this kind of half thought out ‘Tales of Sound and Fury’, which is a precise definition of Melodrama at its best. This film, alas, is not one of those.

That young Tamil women, often silent and traumatised, appeared following Sinhala soldiers in Lankan ‘civil-war cinema’ of the modernists, all male, is a troubling phenomenon. A ‘Sinhala Orientalism’, an exoticising of Tamil and Dalith young women as Other, is at work in some of the civil war films, as in Alborada and Rani. And then this very elevation always leads to unleashing psycho/sexual and/or other forms of violence, because the elevation (Mother Goddess in Alborada) only feeds violent male psychosexual phantasies, which in the Sinhala cinema often leads to the violence of rape and other forms of violence towards women, both Tamil and Sinhala. (To be continued)

by Laleen Jayamanne

Midweek Review

Thirty Thousand and Counting….

Many thousands in the annual grades race,

Are brimming with the magical feel of success,

And they very rightly earn warm congrats,

But note, you who are on the pedestals of power,

That 30,000 or more are being left far behind,

In these no-holds-barred contests to be first,

Since they have earned the label ‘All Fs’,

And could fall for the drug-pusher’s lure,

Since they may be on the threshold of despair…

Take note, and fill their lives with meaning,

Since they suffer for no fault of theirs.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoOTRFU Beach Tag Rugby Carnival on 24th May at Port City Colombo

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRanil’s Chief Security Officer transferred to KKS

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoRemembering Dr. Samuel Mathew: A Heart that Healed Countless Lives

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe Broken Promise of the Lankan Cinema: Asoka & Swarna’s Thrilling-Melodrama – Part IV

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoTrump tariffs and their effect on world trade and economy with particular

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoRadisson Blu Hotel, Galadari Colombo appoints Marko Janssen as General Manager

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCCPI in April 2025 signals a further easing of deflationary conditions

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoA piece of home at Sri Lankan Musical Night in Dubai