Opinion

Educational reforms Sri Lanka demands today for a brighter tomorrow

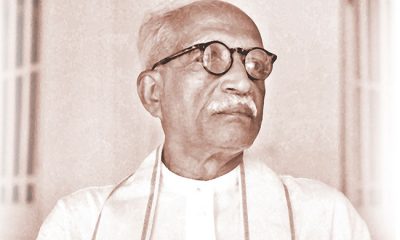

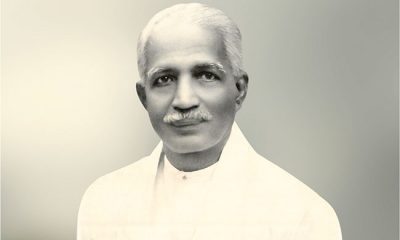

The 32nd Dr. C. W. W. Kannangara Memorial Lecture titled ‘For a country with a future’: Educational reforms Sri Lanka demands today’ delivered by Prof. Athula Sumathipala, Director, Institute for Research and Development, Sri Lanka and Chairman, National Institute of Fundemental Studies, Hanthana on Oct 13 at the National Institute of Education, Maharagama

Continued From Yesterday

Defining the Kannangara legacy of free education to the Sri Lankan nation

It is an unfair comparison to analyse the central approach of the Kannangara educational reforms apart from the context of socio-economic, political conditions, literacy levels and educational opportunities that existed at the time and to consider these reforms under the current context. The primary strategic approach of the reforms was to increase access to education. At that time, in the 1930’s, over half of school-aged children and around three-quarters of school-aged girls did not attend school.

A large proportion of school-aged children being deprived of access to education can be traced back to multiple factors linked to the socio-economic and political situation in that era. Professor Swarna Jayaweera in the second Kannangara Memorial Lecture delivered on 13 October 1989 entitled ‘Expansion of educational opportunity–an unfinished task’, stated that many of the policies presented by Dr. Kannangara were a reaction to colonial education policies that had upset the regional socio-economic, ethnic and religious balance during their rule that extended for over a century. The dual system of education consisting of elite English schools and vernacular schools providing a minimum level education for the masses in either Sinhala or Tamil, the dominance of Christianity within the educational system, favoured status for the South-Western and Northern regions, anomalous economic growth within the country and the focus of education to meet the needs of the colonial economy, were all issues that Lankan policy makers were obliged to deal with in 1931. The aim of establishing 54 Central Colleges (Madhya Maha Vidyalayas) in rural areas throughout the island during 1940-47 was to pave the way for a more equitable distribution of secondary education facilities, which had been limited to urban English schools until then. His aim was ‘to provide free education from childhood to university’.

The executive committee report Dr. Kannangara presented to the State Council of Ceylon gives a clear indication of the core concept of Kannangara reforms. He said “If this esteemed council is able to state that we were able to transform education from something that was considered a birth right of the elite and the wealthy, to a right available at low cost to every child born in this country in the future, if we are able to transform the view on education as a closed book within a sealed box to an open letter that everyone, without regard to their religion, race, caste, can read, then this council can be prouder than Emperor Augustus who claimed that he found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble.”

Dr. Kannangara’s biographer, Mr. K.H.M.Sumathipala, who was a former Secretary of the Department of Education, considers the Kannangara reforms as separable into two distinct eras: the first from 1931 to 1939 and the second from 1939 to 1946. The executive committee had limited powers during the first era and it can be termed a period of minor reforms. The conceptually most important of the reforms during this era is the rural education system, known as the Handessa Scheme, which incorporated practical training and work experience useful to rural societies and economies alongside formal education. This era marks the initial stages of the concept of ‘education for development’ mentioned in Professor Warnasuriya’s lecture. The long-term vision Dr. Kannangara had, clearly displays his concern for the welfare of the rural population of the country.

Dr. Kannangara’s biographer, Mr. K.H.M.Sumathipala, who was a former Secretary of the Department of Education, considers the Kannangara reforms as separable into two distinct eras: the first from 1931 to 1939 and the second from 1939 to 1946. The executive committee had limited powers during the first era and it can be termed a period of minor reforms. The conceptually most important of the reforms during this era is the rural education system, known as the Handessa Scheme, which incorporated practical training and work experience useful to rural societies and economies alongside formal education. This era marks the initial stages of the concept of ‘education for development’ mentioned in Professor Warnasuriya’s lecture. The long-term vision Dr. Kannangara had, clearly displays his concern for the welfare of the rural population of the country.

The years 1939 – 1946 mark the second era, during which the rural school development scheme extended to 250 schools. However, Dr. Kannangara was unable to further expand the scheme as initially planned due to the constraints brought about by drought, a malaria epidemic and the second world war.

The Kannangara reforms themselves are well-documented. In brief, as presented by Dr. Upali Sedere in the 27th Memorial lecture in 2016, they are as follows:

• Free education from kindergarten to university

• Establishing three types of schools – secondary, senior, and vocational schools

• Mother tongue as the medium of instruction at Primary level, bilingual or English medium schools for Junior Secondary level and English schools for Senior Secondary and higher education

• Establishing Central Schools with boarding facilities and scholarships to expand access to higher secondary education

• Introducing religious education

• Facilitating adult education for illiterate adults via Night Schools;

• Institutionalizing regular monthly salaries for teachers;

• Adapting curricula and examinations to suit Sri Lankan conditions

• Establishing an autonomous university

These reforms were approved by the State Council and introduced in October 1944. The increase in the number of schools and the number of teachers as well as the processes introduced to facilitate education led to a significant increase in the number of students completing primary and secondary education – four hundred new schools were constructed during 1944-1948 and 1.2 million students enrolled.

The limited time I have is not at all adequate for an in-depth analysis of the broad vision Dr. Kannangara held. I would like to quote and re-emphasise a few facts stated by Mr. R.S.Medagama in the 25th Memorial Lecture. He states that “The Report of the Special Committee on Education in Ceylon (Sessional Paper XX1V- 1943) contains many ideas on education which the subsequent educational reformers have attempted to accomplish.” Unfortunately, soon after the publication of the report, Dr. Kannangara lost the opportunity to spearhead the implementation of the proposed reforms. Dr. Kannangara also points out the important role education has in promoting unity among different races in the report. In the context of a country divided along multiple lines, it is useful to reiterate some facts he pointed out in the report:

“Our fundamental need is to weld the heterogeneous elements of the population into a nation. The existence of peoples of different racial origins, religions and languages is not peculiar to Ceylon, and history shows that it is by no means impossible to develop a national consciousness even among a population as diverse as ours. There is, indeed, a large common element in our cultures already, and under the stimulation of educational development, the notion of national unity has been growing among us. In planning the future of education in Ceylon we should strive to increase the common element and foster the idea of nationhood.”

“The nationalism that we hope to see established depends for its being on tolerance and understanding. Among a people so varied as ours, any other kind would produce not national unity but national disruption. And the tolerance that we ask our own people to apply to each other we would also wish to see applied to other nations. This tolerance is in fact a characteristic of our citizens. The communities of the island have for many years lived in peace and amity. We are anxious that the teaching in the new educational structure may be inspired by the same tolerance and the same desire for peace among men of all nations” (P10 S.P XX1V, 1943).

Mr. Medagama cited another valuable excerpt from this report: “The most useful citizen is he who can face a new problem and find his own solution. The spark of genius is nothing more than the spark of originality”(p.12 S.P XX1V, 1943).

It is almost unbelievable how a country that initiated a free education system with such a great vision ended up with a toxic culture that is the polar opposite of the original vision. We need to find the root causes of the entrenched problems that we currently face, and find sustainable solutions to these issues.

Before I enter into a discussion of these matters I would like to summarise the key reforms undertaken and the landmarks in education since the time of Dr. Kannangara. This summary section is only up to 2007 needs to be updated from 2007 to 2022, but the limited time did not permit the task.

( To be continued)

Opinion

The minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II

(Continued from January 02, 2026)

From my perspective, it is obvious that Sri Lanka as a country/nation is still left in the lurch politically, economically and morally. The biggest problem is that there is no inspiring leadership. Strong moral leadership is a key component of good governance. ‘Raja bhavatu dhammiko’ (May the ruler be righteous) is the perennial chant of the bhikkhus we hear every morning. A country’s moral leadership is interwoven with its ethical foundation, which, in Sri Lanka’s case, is built on Buddhist moral values, which resonate with the best found in other faiths.

The two dynamic social activist monks, mentioned towards the end of Part I of this article, are being targeted for severe public denunciation as rabid racists in the media in Sri Lanka and abroad due to three main reasons, in my view: First, they are victims of politically motivated misrepresentation; second, when these two monks try to articulate the problems that they want responsible government servants such as police and civil functionaries to address in accordance with the law, they, due to some personality defect, fail to maintain the calm sedateness and composure normally expected of and traditionally associated with Buddhist monks; third, (perhaps the most important reason in this context), these genuine fighters for justice get wrongly identified, in public perception, with other less principled politician monks affiliated to different political parties. Unlike these two socially dedicated monks, monks engaged in partisan politics are a definite disadvantage to the parties they support, especially when they appear on propaganda platforms. The minstrel monk mentioned later in this writeup is one of them.

The occasional rowdy behaviour of Madakalapuwa Hamuduruwo is provoked by the deliberate non-responsiveness of certain unscrupulous government servants of the Eastern Province (who are under the sway of certain racist minority politicians) to his just demands for basic facilities (such as permits for plots of land and water for cultivation) for traditional Sinhalese dwellers in some isolated villages in the area ravaged by war. That is something that the government must take responsibility for. The well-known Galagoda-aththe Thera had long been warning about the Jihadist threat that finally led to the Easter Sunday attacks, but he was in jail when it actually happened. The Yahapalana government didn’t pay any attention to his evidence-based warnings. Instead they shot the messenger. Had the authorities heeded his urgent calls for alarm, the 275 men, women and children dead, and the 500 or so injured, some grievously, would have been safe.

The Mahanayakes should have taken a leaf out of Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith’s book. The Cardinal knows that his responsibility is to look after his flock as a single unanimously approved/accepted leader of the Catholic Church. He fulfills that responsibility well. But, the Mahanayakes couldn’t have resorted to the Cardinal’s strategies which he chooses in accordance with his Catholic/Christian conscience (ultimately fashioned by Christian moral values). The Mahanayakes however, like the Cardinal, could have brought pressure on any one or all of the Presidents and the Prime Ministers elected/appointed since the end of the separatist conflict in 2009 to implement Article 9 of the existing Constitution in its letter and spirit and the powerful earlier Antiquities Ordinance of 1940 fully (I hope it is not in abeyance now) to protect the extensive Buddhist archaeological heritage sites spread throughout the North and East, which have been encroached on and vandalised for decades now, and to look after the poverty-stricken Sinhalese peasants who have somehow managed to survive in the isolated villages in the the Batticaloa District.

A few errant monks, in my opinion, owe their existence primarily to the failure of two groups of people, opportunistic politicians and the indifferent Sangha leadership, to put it plainly. Politicians use monks for securing the Buddhist vote to come to power, and the Mahanayake theras fail to take a united stand against them. As a rule, politicians forget about monks after getting elected to power, apparently, in the hope of not alienating non-Buddhist voters, who naturally favour candidates of their own at elections. Their leaders acquire the influence they need to survive in politics by rubbing those in power the right way. But those non-Buddhist voters are as innocent and peace-loving as the traditionally hoodwinked Buddhist voters.

In this context, I remember having watched a YouTube video uploaded over four months ago featuring MP Namal Rajapaksa. The video (2025-08-30) contained a news clip taken from a mainstream TV channel that showed the young MP being snubbed by a certain Anunayake Thera in Kandy. This was when the MP, during his audience with the high priest, mentioned to him how a retired senior naval officer who had done so much selfless service in ridding the country of Tamil separatist terrorism had been arrested and remanded unjustly (as it appeared) under the present government which is being accused of succumbing unnecessarily to global Tamil diaspora pressure. The monk’s dismissive and insensitive comment in response to MP Namal Rajapaksa’s complaint revealed the senior monk’s blissful ignorance and careless attitude: “We can’t say who is right, who is wrong.” Are we any longer to believe that the Maha Sangha that this monk is supposed to represent are the guardians of the nation?

Please remember that the country has been plunged into the current predicament mainly due to the opportunistic politicians’ policy of politics for politics’ sake and the Mahanaykes’ inexplicable “can’t-be-bothered” attitude. It is not that they are not doing anything to save the country, the people, and the inclusive, nonintrusive Buddhist culture

A young political leadership must emerge free from the potentially negative influence of these factors. SLPP national organiser MP Namal Rajapaksa, among a few other young politicians like him of both sexes, is demonstrating the qualities of a person who could make a successful bid for such a leadership position. In a feature article published in The Island in September 2010 (well over fifteen years ago) entitled ‘Old fossils, out! Welcome, new blood!’ I welcomed young Namal Rajapaksa’s entry into politics on his own merits as a Sri Lankan citizen, while criticising the dynastic ambitions of his father, former president Mahinda Rajapaksa. Namal was already a Cabinet minister then, I think. I have made complimentary observations on his performance as a maturing politician on several occasions in my subsequent writings, most recently in connection with the Joint Opposition ‘Maha Jana Handa’ rally at Nugegoda that he organised on November 21, 2025 on behalf of the SLPP (The Island December 9 and 16). A novel feature he had introduced into his programme was having no monk speakers. I, for one, as a patriotic senior Sri Lankan, wholeheartedly approve of that change from the past. Let monks talk about politics, if they must, from a national platform, not from party political stages. That is, they should provide a disciplined, independent ethical voice on broad societal issues. Ulapane Sumangala Thera is approximating that in his current outspoken criticism of PM Harini Amarasuriya’s controversial education reforms. But I am not sure whether he will continue with non-partisan politics and also infuse some discipline and decency into his speech.

Namal should avoid the trodden path in a plausible manner and get rid of the minstrel monk who insists on accompanying him wherever he goes and tries to entertain your naturally growing audiences with his impromptu recitations”.

This monk reminds me of Rafiki the old mandrill in the 1994 The Lion King animation movie. But there is a world of difference between the monk and the mandrill. The story of The Lion King is an instructive allegory that embodies a lesson for a budding leader. One bright morning, while the royal parents are proudly watching behind him, and, as the sun is rising, Rafiki, the old wise shaman, presents lion king Mufasa’s new born cub, Simba, from the top of Pride Rock to the animals of the Pride Lands assembled below. Rafiki, though a bit of an eccentric old shaman, is a wise spiritual healer, devoted to his royal master, the great king Mufasa, Simba’s father. The film depicts how Simba grows from a carefree cub to a mature king through a life of troubles and tribulations after the death of his father, challenged by his cruel younger brother Scar, Simba’s uncle. Simba learns that ‘true leadership is rooted in wisdom and respect for the natural order, a realisation that contrasts Mufasa’s benevolent rule with Scar’s tyranny’.

Years later, another dawn, animals gather below the Pride Rock, from where Rafiki picks up the wiggling little first born cub of King Simba and Queen Nala and raises him above his head. All the animals cheer and stamp their feet.

The film closes with Simba standing at the top of Pride Rock watching the sunset beyond the western hills.

“Everything is all right, Dad”, Simba said softly. “You see, I remember …. He gazed upward. One by one each star took its place in the cold night sky.

The film describes the Circle of Life, the interconnectedness and interdependence of all living things, and the cycle of birth, death, and renewal. For me, this is a cheerful negation of T.S. Eliot’s pessimistic philosophical reflection on life: “Eating and drinking, dung and death”.

Namal has already developed his inherited political leadership skills, which he will be capable of enhancing further with growing experience. Let’s hope there are other promising, potential young leaders of both sexes as well, to offer him healthy competition eventually, so that, in the future, the country will be ruled by the best leaders. Concluded

by Rohana R. Wasala ✍️

Opinion

A new era of imperial overreach: Venezuela, international law, and the Long Shadow of Empire

The recent illegal bombing of civilian infrastructure in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, followed by the illegal abduction of President Nicolás Maduro and First Lady Cilia Flores, has sent shockwaves across the Global South. These actions represent a profound escalation in the long history of external interference in Latin America. The targeting of power stations, water systems, and other essential facilities has deepened the suffering of ordinary Venezuelans, echoing the strategy used against Iraq in the years preceding the 2003 invasion. Such attacks on civilian infrastructure constitute clear violations of international humanitarian law and may amount to war crimes.

The seizure of Venezuela’s democratically-elected leadership is also an act of international piracy, drawing comparisons to earlier episodes in which powerful states removed leaders who resisted external domination. The assassination of Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in 1961, the invasion of Panama and removal of leader Manuel Noriega in 1989, and the forced removal of Haitian President Jean‑Bertrand Aristide in 2004 come to mind.

The abduction of Maduro and Flores are part of a pattern in which powerful nations intervene to reshape political landscapes in ways that align with their strategic and economic interests. It is part of a series of unilateral US foreign policy decisions, often violating international law, that have drawn significant international criticism.

These developments bring into question the very nature of modern imperialism. The United States’ actions in Venezuela resemble the gunboat diplomacy once practised by the British Empire. During the height of British colonial power, it routinely deployed the Royal Navy to intimidate or coerce nations into compliance. That era only came to a symbolic end when the forces of the newly established People’s Republic of China forced the last British Yangtze gunboat, HMS Amethyst, out of Chinese waters in 1949. The contemporary US interventions, whether through military strikes, unilateral economic sanctions, or covert operations, represent a modernised form of the same imperial logic.

Historical comparisons can also be made to the 1956 Suez Crisis, when Britain, France, and Israel invaded Egypt in an attempt to seize control of the Suez Canal. At that time, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a Republican and former general, stood on the right side of history when he opposed the invasion and joined the international community in pressuring the aggressors to withdraw. Analysts often highlight this moment as an example of the United States aligning itself with anti‑colonial sentiment and the principles of national sovereignty.

This stance was consistent with the ideals of the American Revolution, when George Washington and other revolutionaries resisted the imperial policies of King George III. The British monarch’s actions were widely seen as serving the interests of the East India Company and other commercial elites. Critics of current US foreign policy suggest that the motivations behind recent actions in Venezuela and Iran bear uncomfortable similarities to those earlier imperial dynamics.

According to these perspectives, the pressures placed on Venezuela today are driven by strategic considerations:

- Control over vast oil reserves, among the largest in the world

- Protection of the US dollar from global de‑dollarisation efforts

- Geopolitical positioning against states such as Venezuela and Iran

- Support for Israel, embroiled in a long-standing, illegal occupation of Palestine – opposed actively by both Venezuela and Iran.

These arguments frame the situation not as an isolated incident, but as part of a broader geopolitical strategy reminiscent of the lead‑up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

It seems that President Donald Trump, the driving force behind the illegal aggression against Venezuela and Iran, lacks the sagacity and knowledge of US history of past presidents like George Washington and Eisenhower.The illegal invasion of Iraq by President George W Bush in 2003 embroiled the US in a conflict that denuded its military capacity, depleted the US treasury and accelerated the decline of the US as a world economic and military power.

The US is no longer even as strong as it was prior to the Iraq invasion. The Russo-Ukraine war has revealed the weakness of the Western military, both in production and technological terms – the US has been forced to reverse-engineer Iranian drones, for example. The US economy is reeling, its apparent strength in GDP terms belied by its lack of productive capability.

The attempts by the US to isolate its perceived enemies through sanctions and expropriations of foreign reserves have backfired. Foreign governments are reluctant to buy US bonds – essential for keeping the American economy afloat. The de-dollarisation trend has accelerated, as nations seek to protect themselves from unilateral US economic action.

Trump’s blatant disregard for international law in his treatment of both Venezuela and Iran are likely to force countries of the Global South to seek alternative groupings to safeguard themselves from US aggression. The growth of the Shanghai Co-operation Organisation and the establishment of the Alliance of Sahel States are symptomatic of the unease of the Global South.

The unfolding crisis in Venezuela has therefore become a focal point for debates about sovereignty, international law, and the future of global power relations. For many in the Global South, the events are viewed through the lens of historical memory of colonialism, intervention, and the struggle for self‑determination. Whether the international community will respond with the same unity that confronted the Suez invasion remains to be seen, but the stakes for global norms and regional stability are undeniably high.

lens of historical memory of colonialism, intervention, and the struggle for self‑determination. Whether the international community will respond with the same unity that confronted the Suez invasion remains to be seen, but the stakes for global norms and regional stability are undeniably high.

(Asia Progress Forum is a collective of like-minded intellectuals, professionals, and activists dedicated to building dialogue that promotes Sri Lanka’s sovereignty, development, and increasing leadership in the Global South.)

by Asia Progress Forum

Opinion

Structural Failures and Economic Consequences in Sri Lanka – Part II

Research and Development in Crisis:

(Part I of this article appeared in The Island of 07. 12. 2025)

China and India as Unequal Competitors

China and India did not emerge as global economic powers through unrestricted exposure to international competition. Their industrial sectors benefited from decades of state support, protected domestic markets, subsidised inputs, and coordinated innovation policies. Public investment in R&D, infrastructure, and human capital created conditions for large-scale, low-cost production.

Sri Lankan producers, by contrast, operate in a vastly different environment. They face high energy costs, limited access to capital, weak logistics, and minimal state support. Expecting them to compete directly with Chinese or Indian manufacturers without comparable policy backing is economically unrealistic and strategically unsound. Treating global competition as inherently fair ignores structural asymmetries. Without deliberate policy intervention, Sri Lanka will remain a consumption-oriented economy dependent on external production. Recognising unequal competition is the first step toward designing realistic, protective, and development-oriented R&D policies.

University Research Under Structural Threat

University-based research in Sri Lanka is facing a structural crisis that threatens its long-term viability. Universities remain the primary centers of knowledge generation, yet they are constrained by rigid administrative systems, inadequate funding, and limited autonomy. Academic research is often treated as an auxiliary activity rather than a core institutional mandate, resulting in heavy teaching loads that leave minimal time for meaningful research engagement.

A major challenge is that university innovations frequently remain confined to academic outputs with little societal or economic impact. Research success is measured primarily through publications rather than problem-solving or commercialisation. This disconnect discourages applied research and weakens university-industry linkages. Consequently, many promising innovations never progress beyond the proof-of-concept stage, despite strong potential for real-world application.

Publication itself has become a financial burden for researchers. The global shift toward open-access publishing has transferred costs from readers to authors, with publication fees commonly ranging from USD 3,000 to 4,500. For Sri Lankan academics, these costs are prohibitive. The absence of national publication support mechanisms forces researchers to either publish in low-visibility outlets or self-finance at personal financial risk, further marginalising Sri Lankan scholarship globally.

Limited Access to International Conferences

International conferences play a critical role in the research ecosystem by facilitating knowledge exchange, collaboration, and visibility. They provide platforms for researchers to present findings, receive peer feedback, and establish professional networks that often lead to joint projects and external funding. However, Sri Lankan researchers face severe constraints in accessing these opportunities due to limited institutional and national funding.

Conference participation is frequently viewed as discretionary rather than essential. Funding allocations, where they exist, are insufficient to cover registration fees, travel, and accommodation. As a result, researchers often rely on personal funds or forego participation altogether. This disproportionately affects early-career researchers, who most need exposure and mentorship to establish themselves internationally.

The cumulative effect of limited conference participation is scientific isolation. Sri Lankan research becomes less visible, collaborations decline, and awareness of emerging global trends weakens. Over time, this isolation reduces competitiveness in grant applications and limits the country’s ability to integrate into global research networks, further entrenching systemic disadvantage.

International Patents and Missed Global Markets

Given the limitations of the domestic market, international markets offer a vital opportunity for Sri Lankan innovations. However, accessing these markets requires robust intellectual property protection beyond national borders. International patenting is expensive, complex, and legally demanding, placing it beyond the reach of most individual researchers and institutions in Sri Lanka.

Without state-backed support mechanisms, local innovators struggle to file, maintain, and enforce patents in foreign jurisdictions. Costs associated with Patent Cooperation Treaty applications, national phase entries, and legal representation are prohibitive. As a result, many innovations are either not patented internationally or are disclosed prematurely through publication, rendering them vulnerable to appropriation by foreign entities.

This failure to protect intellectual property globally results in lost export opportunities and diminished national returns on research investment. Technologies with potential relevance to global markets particularly in agriculture, veterinary science, and biotechnology remain underexploited. A systematic approach to international patenting is essential if Sri Lanka is to transition from a knowledge generator to a knowledge exporter.

Bureaucratic Barriers to International Collaboration

International research collaboration is increasingly essential in a globalized scientific environment. Partnerships with foreign universities, research institutes, and funding agencies provide access to advanced facilities, diverse expertise, and external funding. However, Sri Lanka’s bureaucratic processes for approving international collaborations remain excessively slow and complex.

Memoranda of Understanding with foreign institutions often require multiple layers of approval across ministries, departments, and governing bodies. These procedures can take months or even years, by which time funding windows or collaborative opportunities have closed. Foreign partners, accustomed to efficient administrative systems, frequently withdraw due to uncertainty and delay.

This bureaucratic inertia undermines Sri Lanka’s credibility as a research partner. In a competitive global environment, countries that cannot respond quickly lose opportunities. Streamlining approval processes through delegated authority and single-window mechanisms is critical to ensuring that Sri Lanka remains an attractive destination for international research collaboration.

Research Procurement and Audit Constraints

Rigid procurement regulations pose one of the most immediate operational challenges to research in Sri Lanka. Scientific research often requires highly specific reagents, equipment, or consumables that are available only from selected suppliers. Standard procurement rules, which mandate multiple quotations and lowest-price selection, are poorly suited to the realities of experimental science.

In biomedical and veterinary research, for example, reproducibility often depends on using antibodies, kits, or reagents from the same manufacturer. Substituting products based solely on price can alter experimental outcomes, compromise data integrity, and invalidate entire studies. Even though procurement officers and auditors frequently lack the scientific background to appreciate these nuances.

Lengthy procurement processes further exacerbate the problem. Delays in acquiring time-sensitive materials disrupt experiments, extend project timelines, and increase costs. For grant-funded research with fixed deadlines, such delays can result in underperformance or loss of funding. Procurement reform tailored to research needs is therefore essential.

Audit Practices Misaligned with Research and Innovation

While financial accountability is essential in publicly funded research, audit practices in Sri Lanka often fail to recognize the distinctive and uncertain nature of scientific and innovation-driven work. Auditors trained primarily in general public finance frequently apply rigid procedural interpretations that are poorly aligned with research timelines, intellectual property development, and iterative experimentation. This disconnect results in frequent audit queries that challenge legitimate scientific, technical, and strategic decisions made by research teams.

There are documented instances where principal investigators and research teams are questioned by auditors regarding the timing of patent applications, perceived delays in filing, or outcomes of the patent review process. In such cases, responsibility is often inappropriately placed on investigators, rather than on structural inefficiencies within patent authorities, institutional IP offices, or prolonged examination timelines beyond researchers’ control. This misallocation of accountability creates an environment where researchers are penalized for systemic failures, discouraging engagement with the patenting process altogether.

Lengthy patent application review periods often extending beyond the duration of time-bound, grant-funded projects can result in incomplete, weakened, or abandoned patents. When reviewer feedback or amendment requests arrive after project closure, research teams typically lack funding to conduct additional validation studies, refine claims, or seek legal assistance. Despite these structural constraints, audit queries may still cite “delays” or “non-compliance” by investigators, further exacerbating institutional risk aversion and undermining innovation incentives.

Beyond patent-related issues, researchers are compelled to spend substantial time responding to audit observations, justifying procurement decisions, or explaining complex methodological choices to non-specialists. This administrative burden diverts time and intellectual energy away from core research activities and contributes to frustration, demoralization, and reduced productivity. In extreme cases, fear of audit repercussions leads researchers to avoid ambitious, interdisciplinary, or translational projects that carry higher uncertainty but greater potential impact.

The absence of structured dialogue between auditors, patent authorities, institutional administrators, and the research community has entrenched mistrust and inefficiency. Developing research-sensitive audit frameworks, training auditors in the fundamentals of scientific research and intellectual property processes, and clearly distinguishing individual responsibility from systemic institutional failures would significantly improve accountability without undermining innovation. Effective accountability mechanisms should enable scientific excellence and economic translation, not constrain them through procedural rigidity and misplaced blame.

Limited Training and Capacity-Building Opportunities

Continuous training and capacity building are essential for maintaining a competitive research workforce in a rapidly evolving global knowledge economy. Advances in methodologies, instrumentation, data analytics, and regulatory standards require researchers to update their skills regularly. However, opportunities for structured training, advanced short courses, and technical skill enhancement remain extremely limited in Sri Lanka.

Funding constraints significantly restrict access to international training programs and specialized workshops. Overseas short courses, laboratory attachments, and industry-linked training are often beyond institutional budgets, while national-level training programs are sporadic and narrow in scope. As a result, many researchers rely on self-learning or informal knowledge transfer, which cannot fully substitute for hands-on exposure to cutting-edge techniques.

The absence of systematic capacity-building initiatives creates a widening skills gap between Sri Lankan researchers and their international counterparts. This gap affects research quality, competitiveness in grant applications, and the ability to absorb advanced foreign technologies. Without sustained investment in human capital development, even increased research funding would yield limited returns.

From Discussion to Implementation

Sri Lanka does not lack policy dialogue on research and innovation. Numerous reports, committee recommendations, and strategic plans have repeatedly identified the same structural weaknesses in funding, commercialization, governance, and market access. What is lacking is decisive implementation backed by political commitment and institutional accountability.

Protecting locally developed R&D products during their infancy, reforming procurement and audit systems, stabilizing fiscal policy, and supporting publication and conference participation are not radical interventions. They are well-established policy instruments used by countries that have successfully transitioned to innovation-led growth. The failure lies not in policy design but in execution and continuity. Implementation requires a shift in mindset from viewing R&D as a cost to recognizing it as a strategic investment. This shift must be reflected in budgetary priorities, administrative reforms, and measurable performance indicators. Without such alignment, discussions will continue to cycle without tangible impact on the ground.

Conclusion: Choosing Between Dependence and Innovation

Sri Lanka stands at a critical crossroads in its development trajectory. Continued neglect of research and development will lock the country into long-term technological dependence, import reliance, and economic vulnerability. In such a scenario, local production capacity will continue to erode, skilled human capital will migrate, and national resilience will weaken. Alternatively, strategic investment in R&D, coupled with protective and enabling policies, can unlock Sri Lanka’s latent innovation potential. Sustained funding, institutional reform, quality enforcement, and market protection for locally developed products can transform research outputs into engines of growth. This path demands patience, policy consistency, and political courage.

As Albert Einstein aptly has aptly us, “The true failure of research lies not in unanswered questions, but in knowledge trapped by institutional, financial, and systemic barriers to dissemination.” The choice before Sri Lanka is therefore not between consumers and producers, nor between openness and protection. It is between short-term convenience and long-term national survival. Without decisive action, Sri Lanka risks outsourcing not only its production and innovation, but also its future.

Prof. M. P. S. Magamage is a senior academic and former Dean of the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the Sabaragamuwa University of Sri Lanka. He has also served as Chairman of the National Livestock Development Board of Sri Lanka and is an accomplished scholar with extensive national and international experience. Prof. Magamage is a Fulbright Scholar, Indian Science Research Fellow, and Australian Endeavour Fellow, and has served as a Visiting Professor at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, USA. He has published both locally and internationally reputed journals and has made significant contributions to research commercialization, with patents registered under his name. His work spans agricultural sciences, livestock development, and innovation-led policy engagement. E-mail: magamage@agri.sab.ac.lk

by Prof. M. P. S. Magamage

Sabaragamuwa University of

Sri Lanka

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoInterception of SL fishing craft by Seychelles: Trawler owners demand international investigation

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoBroad support emerges for Faiszer’s sweeping proposals on long- delayed divorce and personal law reforms

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoThe Venezuela Model:The new ugly and dangerous world order

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoPrez seeks Harsha’s help to address CC’s concerns over appointment of AG

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoPrivate airline crew member nabbed with contraband gold

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoWarning for deep depression over South-east Bay of Bengal Sea area

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoIndian Army Chief here