Midweek Review

A Special Forces officer’s narrative

‘Deperamunaka Satan’ dealt with several issues that hadn’t been addressed by ex-military men who shared their experiences before Maj. Gen. Dhammi Hewage launched his controversial memoirs seven months ago. The chapter on wartime recruitment underscored the importance of sustained process and the readiness on the part of the Army to inspire youth and the unprecedented impact made by entrepreneur Dilith Jayaweera, one of the presidential aspirants now, to help the armed forces to recruit required personnel. Jayaweera, who had been a classmate of Hewage at St Aloysius, Galle, in fact for the first time met the then Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa with the intervention of late Bandula Jayasekera, the then Editor of the Daily News. That meeting led to a massive Triad-led advertising campaign that achieved the unthinkable. Hewage’s narrative is a must read for those interested in the Eelam conflict.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Fighting was raging in the Vanni in 2008. The 57 Division, tasked to regain Kilinochchi, was facing stiff resistance, while Task Force 1 (TF1) battled the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) units at a higher pace, on a wider front, also in the Vanni west, particularly in the formidable Madhu jungle terrain, which prompted some armchair experts in Colombo to predict that the Army would not come out of it in one piece.

One sarcastic scribe from another newspaper even went to the extent of claiming that the Army would be swallowed up by the LTTE in those jungles.

When Rohan Abeywardena, now with The Island, on behalf of The Sunday Times, raised that possibility, with the Task Force 1 that was still based in the Mannar Rice Bowl region, Major Harendra Ranasinghe of the Special Forces, at his makeshift field office, declared they had prepared well for jungle warfare and were ready as never before. Despite so many naysayers in Colombo they truly proved their mettle in next to no time. Ranasinghe later retired as a Major General without any fanfare.

The Army faced severe shortage of officers and men as fighting Divisions slowly but steadily advanced towards enemy strongholds along numerous thrusts as never before.

The LTTE gradually retreated towards Vanni east but posed quite a formidable threat. Both Pooneryn and Elephant Pass-Kilinochchi section of the Kandy-Jaffna A-9 road remained under its control.

Regardless of stepped-up recruitment, the Army lacked sufficient troops to hold areas that were brought back under government control. Growing casualties further increased the pressure on the fighting Divisions.

Then Major Dhammi Hewage, stationed at Volunteer Force headquarters, Battaramulla, having received an order from Army headquarters, reported to Vanni Security Forces headquarters where he was directed to 611 Brigade. Major Hewage was given the unenviable task of protecting the 15 km Main Supply Route (MSR) from Kalmadu junction to Kirisuddan.

In the absence of fighting troops, the bold officer was assigned medically downgraded personnel. There hadn’t been a single combat ready soldier under Major Hewage’s command and of them approximately 80 percent openly dissented and challenged the Army headquarters’ move.

But the then Lt. Gen. Sarath Fonseka’s Army was not inclined to tolerate dissent. Having served the Army for just over 35 years, Hewage retired as a Major General in August 2022 in the wake of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s ouster. At the inception of the then Second Lieutenant Hewage’s somewhat controversial military career, he had first served under the then Lieutenant Colonel Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who functioned as the Military Coordinating Officer, Matale district (May 1989-January 1990).

Hewage launched his memoirs ‘Deperamunaka Satan’ (Battles on Two Fronts) in September last year, a couple of months before Gotabaya Rajapaksa published ‘The Conspiracy to Oust Me from Presidency’, the latter however was far more blunt and dealt with the failure on the part of the military and police to protect their constitutionally elected government.

‘Deperamunaka Satan’

is certainly an immensely readable and hugely stimulating memoir of an officer, who had served the elite Special Forces after being moved from the celebrated Gajaba Regiment to the Rapid Deployment Force (RDF). The author quite easily captured the attention of the reader as he described his meeting with then Lieutenant Shavendra Silva at Saliyapura, Anuradhapura, where he was told of an opportunity to join the RDF.

Having passed out as a Second Lieutenant, in late June 1989, Hewage had been in command of a platoon of the first battalion of the Gajaba Regiment (IGR) deployed on a hill top near Ovilikanda.

On a specific directive of Lt. Col. Rajapaksa, the then Commanding Officer of 1GR, Hewage’s platoon comprising 25 personnel had been deployed there to provide protection to workers of a private firm hired to build four new power pylons to replace those destroyed by the then proscribed Janatha Vimukthi Peremuna (JVP).

It would be pertinent to mention that President Ranasinghe Premadasa, having entered into a clandestine deal with the LTTE, provided arms, ammunition and funds to the group. The LTTE caused quite significant losses on the Indian Peace Keeping Force no sooner they were deployed here under the controversial Indo-Lanka Accord that was forced on us by New Delhi, during the July 1987 and March 1990 period. The Premadasa-Prabhakaran ‘honeymoon,’ however, only lasted for about 14 months, when the LTTE turned its guns against the Premadasa government that nurtured it unwisely hoping that the Tigers would change with proper incentives. The LTTE resumed the war in June 1990, after India withdrew its Army in March 1990 at the request of President Premadasa.

If not for my colleague Harischandra Gunaratne’s offer of ‘Deperamunaka Satan’, the writer could have missed it though Captain Wasantha Jayaweera, also of the Special Forces, alerted me to the launch of the retired Maj. General’s work late last year. Incidentally, Jayaweera, had been quoted in the heart-breaking chapter that dealt with the catastrophic heli-borne landing, death of Special Forces pioneer Colonel Aslam Fazly Laphir and the humiliating fall of the isolated Mullaithivu Army Camp in July 1996 during Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s tenure as the President. Mullaithivu had been the home to the Army’s 25 Brigade. That loss sent shock waves through the defence establishment but, four years later, the LTTE delivered a massive blow to the Army when a Division plus troops couldn’t thwart the LTTE offensive directed at Elephant Pass.

An unprecedented ‘hit’

One of the most intriguing episodes dealt with Maj. Hewage led an attack on an LTTE group positioned in the jungles off Pompemadu without knowing their identity.

In the absence of a suitable contingent of troops for immediate deployment, Hewage had led a group of disabled men through the jungles to take on the LTTE after another patrol consisting of medically downgraded men spotted the enemy but refrained from engaging them.

Why did Hewage risk his life and the precious lives of medically condemned (categorized) men under his command? What did he really expect to achieve in such circumstances? Or was he trying to prove a point to some of his seniors or just acted recklessly on the spur-of-the-moment?

At one point they stopped firing fearing the group under fire by them were either Special Forces or Commandos. But, a shouted question and response in Tamil prompted them to fire everything they had until the group was eliminated.

The ragtag group of soldiers, led by Hewage, after the successful firefight, found four Tiger bodies along with a whole lot of equipment, including a satellite phone and two Global Positioning Systems, that led the Division Commander, then Brigadier Piyal Wickremaratne, to declare that the vanquished enemy unit were members of the LTTE Long Range Patrol.

Hewage’s response to Brig. Wickremaratne’s heartless query as to why bodies of LTTE LRP hadn’t been brought to his base and the circumstances Division Commander’s directive to recover them was not carried out, captured the imagination of the readers.

Interception of enemy communications, within 24 hours after the ‘hit’ off Pompemadu, revealed that the ‘neutralized’ LRP had been tasked with moving some Black Tiger suicide cadres, suicide jackets and other equipment from Puthukudirippu to Anuradhapura, having crossed the Kandy-Jaffna road. The Army ascertained that the LRP had been on its way back to Puthukudirippu after having safely moved a Black Tiger group to Anuradhapura.

There couldn’t have been a similar ‘hit’ during the entire war. Unfortunately, for want of follow up action to highlight the success of his men under trying circumstances, on the part of Hewage, the disabled men were denied an opportunity to receive at least the distinguished RWP (Ranawickrema Padakkama) award.

Hewage’s perspective is important. His narrative is not ordinary or simply a case of blowing his own trumpet, but a genuine bid to present an untold story that may not be to the liking of some of his seniors or of those on the same level.

But, Hewage’s is an inspiring story, especially at a time the military earned severe criticism of some due to shortcomings of a few in higher places. The social media onslaught on selected officers, both serving and retired, has worsened the situation. The devastating allegations by former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, himself an ex-frontline combat veteran, that the Army failed in its responsibility to protect the elected President made an already bad situation far worse and intolerable.

From Maduru Oya to Kalawanchikudi

Having undergone, perhaps, the toughest training available at that time for elite fighting men at Maduru Oya where Counter Revolutionary Warfare Wing (CRW Wing) is situated, Hewage had been one of the 16 officers to pass out without a parade. All 16 officers who had been there, at the beginning of the training, were fortunate to pass out after the grueling course, though of 483 other rankers, who underwent training at the same time, only 181 were able to complete it.

Of Hewage’s Gajaba contingent (1 officer/30 other rankers) that had been sent for the training, only he and three others, including Lance Corporal Chandrapala, lasted the training period that comprised basic and advance training.

There had been peace in the Northern and Eastern Provinces at that time as President Premadasa played pandu with the LTTE. The group that included Hewage passed out from Maduru Oya during peace time and perhaps seemed to have been unaware of the resumption of the Eelam War with far bolder Tigers ranged against them after having given a bloody nose to the IPKF. However, the then Major Jayavi Fernando, who had been a senior instructor at Maduru Oya, warned those undergoing training there the war was coming. One of the key Special Forces pioneers, Fernando issued the warning at the commencement of the training and at the end of it when he declared let us go to hell. That warning was followed up by a serving of tea.

Having joined The Island in early June 1987 as a trainee reporter, this correspondent had an opportunity to cover the conflict in the North and East as well as the second southern savage uprising, perpetrated by the JVP, and an equally or more violent campaign by the forces to put it down. The time Hewage passed out from Maduru Oya had been dicey as President Premadasa, obviously duped by the LTTE, bent backwards to appease them.

On the orders of the President, the then Army Commander Lt. Gen. Hamilton Wanasinghe (1988-1991) cooperated with the LTTE. The President went to the extent of releasing money to the LTTE, even after the Eelam War II erupted with the disgraceful betrayal of the police and the Army. Fortunately, the Army disregarded the President’s directive. President Premadasa released as much as Rs 125 mn during the 1989/1990 period through the then Treasury Secretary R. Paskaralingham as he remained supremely confident the LTTE could be won over through such strategies. The LTTE proved the President wrong and the consequences, as all of us know, were devastating.

Author Hewage made reference to the formation of the Tamil National Army (TNA) by the Indian government. Although Hewage didn’t touch the issue in detail, that reference should be appreciated as the formation of the TNA should be considered taking into consideration the overall Indian strategy at that time as New Delhi sought to somehow sustain Vartharaja Perumal’s EPRLF-led administration.

Two incidents that would attract the readers were an injury suffered by Hewage while undergoing training at Maduru Oya, where he faced the threat of expulsion, and the death of Second Lieutenant Priyantha Gunawardena, on Nov 17th, 1989, at Kalmunai, during clashes between government forces and the IPKF. The death of Gunawardena caused an immense impact on Hewage, and the colleagues of the dead junior officer, of the 28th Intake, wanted two days leave to attend the funeral. When they sought approval from Maj. Jayavi Fernando, the officer’s no nonsense response must have been received as a warning.

Hewage quoted Fernando, known for his efficient, direct and quite blunt approach whatever the circumstances were, as having told them that the Kalmunai incident was only the beginning. The real war hadn’t even started yet. Gunawardena was the first batch-mate of yours to die. Many more people would die. It would be far more important to complete the course and be ready for the Eelam War II. Once you complete the training you may visit the home of the late colleague. Maj. Jayavi Fernando retired on Oct 31, 1998 during the disastrous Operation ‘Jayasikuru’ (Victory Assured) that was meant to restore Overland MSR from Vavuniya to Elephant Pass. Fernando’s shock retirement caused a severe loss of morale to the Army at a time it was under tremendous pressure not only in the Vanni but in all other theatres as well.

Hewage dealt with the killing of Second Lieutenant Deshapariya also of the Special Forces and his buddy (an assistant assigned to an officer from the time he passes out from the Military Academy) at Galagama where their bodies were set ablaze by the JVP, their deployment at the Engineers’ detachment at Tissamaharama and the sudden appearance of Maj. Laphir of the same detachment on June 13, 1990.

Within 24 hours, they were on their way to Weerwawila where officers, including Maj Laphir, joined the flight to Uhana whereas administrative troops accompanied supplies and other equipment were dispatched overland.

Hewage lovingly recalled how ordinary people waved lion flags to show their support to security forces as they travelled overland from Uhana airport to Ampara against the backdrop of punitive measures taken by the Army against JVP terrorists.

By the time the Army started building up strength the LTTE had massacred several hundred police personnel who had surrendered to them on another foolish directive issued by President Premadasa. Having named the senior officers who had arrived in Ampara to neutralize the LTTE threat, Hewage described the pressure on then Ampara Coordinating Officer then Brig.Rohan de S. Daluwatte was under as he struggled to cope up with the developing scenario.

Hewage gave an extremely good description of the fighting and incidents which involved his unit at a time the Army lacked actual combat experience as there hadn’t been any operations since India compelled Sri Lanka to halt ‘Operation Liberation’ in June 1987 that was meant to clear the Vadamatchchy region in the Jaffna peninsula, which included Velvettiturai, the home town of LTTE Leader Velupillai Prabhakaran.

The Army was suddenly forced to resume both defensive and offensive operations in the aftermath of the massacre of the surrendered police personnel in the East. By the end of 1990, the Army lost control of the Kandy-Jaffna A9 road and remained under LTTE control till Dec 2008/January 2009 when Brigadier Shavendra Silva’s celebrated Task Force 1, subsequently named 58 Division, cleared the Elephant Pass-Kilinochchi south stretch and met Maj. Gen. Jagath Dias’s 57 Division at Kilinochchi.

Hewage called the infamous instructions issued from Colombo during Ranasinghe Premadasa’s tenure as the President to all military installations to surrender to the LTTE pending negotiations. In spite of some police stations accepting the directive, other bases refused point blank. Hewage mentioned with pride how the Commanding Officer at Kalawanchikudy detachment Captain Sarath Ambawa defied those instructions and asked personnel at the neighbouring police station not to surrender but to seek protection at his base. A section of the police surrendered to the LTTE against the Captain’s wishes and were executed but 11 policemen ran across open space to reach the Kalawanchikudy Army detachment. One of them, Constable Ukku Banda succumbed to injuries he suffered as a result of LTTE fire.

Negotiations between Maj. Laphir and a local LTTE leader on the partially damaged Kokkadhicholai bridge in a bid to cross it while the then Foreign Minister A.C.S. Hameed was in Jaffna to work out a last minute ceasefire and the first Sia Marchetti attack (witnessed by Hewage) a little distance away from the bridge and later crossing the river under threat of enemy fire make interesting reading.

Trouble within

Hewage shared his first-hand experience in the 1990 Mullaithivu battle, followed by rescuing of troops trapped in Jaffna Fort also in the same year, various smaller operations in the Eastern theatre and an incident in mid-1994 at Maduru Oya where at the conclusion of risky bunker busting drill he caused an injury to private Rajapaksa, unintentionally resulting in severe repercussions.

Hewage discussed how his seniors exploited that incident to harass him though five years later Corporal Rajapakse served as his buddy during his stint in Jaffna as the Commanding Officer of Combat Rider Team.

Regardless of consequences, Hewage had been courageous and reckless to take decisions on his own on the battlefield and his description of wife of a senior officer based at Maduru Oya over her requirement to secure the services of a civilian cook with the Army is hilarious but later the difficulties the author experienced at his new appointment at the Special Forces Regimental Centre, Seeduwa, and the death of Special Forces man in the hands of Military Police investigating the disappearance of two Browning pistols and two Beretta semi-automatic pistols at their Naula camp explained the turmoil within.

Hewage had been harsh on some of his seniors, including Maj. Gen. Gamini Hettiarachchi, widely considered the Father of Special Forces and Field Marshal Sarath Fonseka whom he accused of depriving him of an opportunity to command 10 GR at that time headquartered at Akkarayankulam.

Hewage quoted the then Army Chief Lt. Gen. Sarath Fonseka as having told the then Gajaba Regimental Commander Maj. Gen. Jagath Dias he (Hewage) created a problem at Volunteer Force headquarters.

Don’t even make him Grade 1. Declaring that he realized he wouldn’t receive a command appointment as long as the war-winning Army Chief remained in office, Hewage said that he finally took over 9 GR on Sept 09, 2011 when Fonseka was under the custody of the Navy.

Hewage hadn’t minced his words as he boldly presented a controversial narrative, regardless of consequences.

Midweek Review

Fonseka clears Rajapaksas of committing war crimes he himself once accused them of

With Sri Lanka’s 17th annual war victory over separatist Tamil terrorism just months away, warwinning Army Chief, Field Marshal Sarath Fonseka (Dec. 06, 2005, to July 15, 2009) has significantly changed his war narrative pertaining to the final phase of the offensive that was brought to an end on May 18, 2009.

The armed forces declared the conclusion of ground operations on that day after the entire northern region was brought back under their control. LTTE leader Velupillai Prabhakaran, hiding within the secured area, was killed on the following day. His body was recovered from the banks of the Nanthikadal lagoon.

With the war a foregone conclusion, with nothing to save the increasingly hedged in Tigers taking refuge among hapless Tamil civilians, Fonseka left for Beijing on May 11, and returned to Colombo, around midnight, on May 17, 2009. The LTTE, in its last desperate bid to facilitate Prabhakatan’s escape, breached one flank of the 53 Division, around 2.30 am, on May 18. But they failed to bring the assault to a successful conclusion and by noon the following day those fanatical followers of Tiger Supremo, who had been trapped within the territory, under military control, died in confrontations.

During Fonseka’s absence, the celebrated 58 Division (formerly Task Force 1), commanded by the then Maj. Gen. Shavendra Silva, advanced 31/2 to 4 kms and was appropriately positioned with Maj. Gen. Kamal Gunaratne’s 53 Division. The LTTE never had an opportunity to save its leader by breaching several lines held by frontline troops on the Vanni east front. There couldn’t have been any other option than surrendering to the Army.

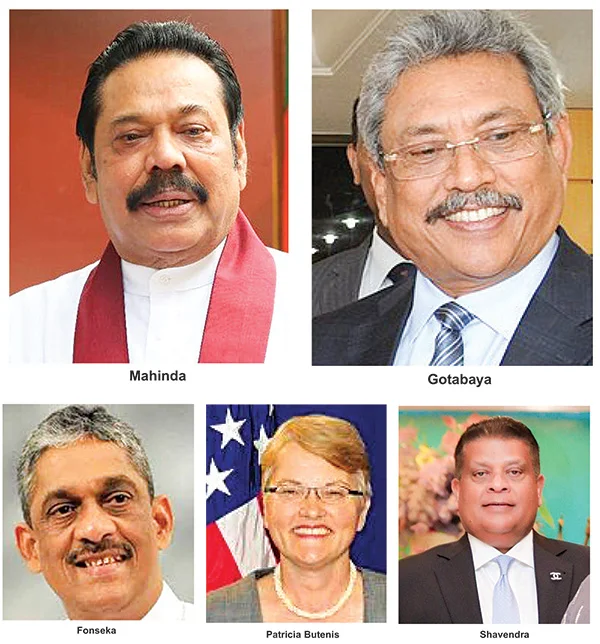

The Sinha Regiment veteran, who had repeatedly accused the Rajapaksas of war crimes, and betraying the war effort by providing USD 2 mn, ahead of the 2005 presidential election, to the LTTE, in return for ordering the polls boycott that enabled Mahinda Rajapaksa’s victory, last week made noteworthy changes to his much disputed narrative.

GR’s call to Shavendra What did the former Army Commander say?

* The Rajapaksas wanted to sabotage the war effort, beginning January 2008.

* In January 2008, Mahinda Rajapaksa, Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Navy Commander VA Wasantha Karannagoda, proposed to the National Security Council that the Army should advance from Vavuniya to Mullithivu, on a straight line, to rapidly bring the war to a successful conclusion. They asserted that Fonseka’s strategy (fighting the enemy on multiple fronts) caused a lot of casualties.

* They tried to discourage the then Lt. Gen. Fonseka

* Fonseka produced purported video evidence to prove decisive intervention made by Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa on the afternoon of May 17. The ex-Army Chief’s assertion was based on a telephone call received by Maj. Gen. Shavendra Silva from Gotabaya Rajapaksa. That conversation had been captured on video by Swarnavahini’s Shanaka de Silva who now resides in the US. He had been one of the few persons, from the media, authorised by the Army Headquarters and the Defence Ministry to be with the Army leadership on the battlefield. Fonseka claimed that the videographer fled the country to escape death in the hands of the Rajapaksas. It was somewhat reminiscent of Maithripala Sirisena’s claim that if Rajapaksas win the 2015 Presidential election against him he would be killed by them.

* Shanaka captured Shavendra Silva disclosing three conditions laid down by the LTTE to surrender namely (a) Their casualties should be evacuated to Colombo by road (b) They were ready to exchange six captured Army personnel with those in military custody and (c) and the rest were ready to surrender.

* Then Fonseka received a call from Gotabaya Rajapaksa, on a CDMA phone. The Defence Secretary issued specific instructions to the effect that if the LTTE was to surrender that should be to the military and definitely not to the ICRC or any other third party. Gotabaya Rajapaksa, one-time Commanding Officer of the 1st battalion of the Gajaba Regiment, ordered that irrespective of any new developments and talks with the international community, offensive action shouldn’t be halted. That declaration directly contradicted Fonseka’s claim that the Rajapaksas conspired to throw a lifeline to the LTTE.

Fonseka declared that the Rajapaksa brothers, in consultation with the ICRC, and Amnesty International, offered an opportunity for the LTTE leadership to surrender, whereas his order was to annihilate the LTTE. The overall plan was to eliminate all, Fonseka declared, alleging that the Rajapaksa initiated talks with the LTTE and other parties to save those who had been trapped by ground forces in a 400 m x 400 m area by the night of May 16, among a Tamil civilian human shield held by force.

If the LTTE had agreed to surrender to the Army, Mahinda Rajapaksa would have saved their lives. If that happened Velupillai Prabhakaran would have ended up as the Chief Minister of the Northern Province, he said. Fonseka shocked everyone when he declared that he never accused the 58 Division of executing prisoners of war (white flag killings) but the issue was created by those media people embedded with the military leadership. Fonseka declared that accusations regarding white flag killings never happened. That story, according to Fonseka, had been developed on the basis of the Rajapaksas’ failed bid to save the lives of the LTTE leaders.

Before we discuss the issues at hand, and various assertions, claims and allegations made by Fonseka, it would be pertinent to remind readers of wartime US Defence Advisor in Colombo Lt. Col. Lawrence Smith’s June 2011 denial of white flag killings. The US State Department promptly declared that the officer hadn’t spoken at the inaugural Colombo seminar on behalf of the US. Smith’s declaration, made two years after the end of the war, and within months after the release of the Darusman report, dealt a massive blow to false war crimes allegations.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, in 2010, appointed a three-member Panel of Experts, more like a kangaroo court, consisting of Marzuki Darusman, Yasmin Sooka, and Steven Ratner, to investigate war crimes accusations.

Now Fonseka has confirmed what Smith revealed at the defence seminar in response to a query posed by Maj. General (retd.) Ashok Metha of the IPKF to Shavendra Silva, who had been No 02 in our UN mission, in New York, at that time.

White flag allegations

‘White flag’ allegations cannot be discussed in isolation. Fonseka made that claim as the common presidential candidate backed by the UNP-JVP-TNA combine. The shocking declaration was made in an interview with The Sunday Leader Editor Frederica Jansz published on Dec. 13, 2009 under ‘Gota ordered them to be shot – General Sarath Fonseka.’

The ‘white flag’ story had been sensationally figured in a leaked confidential US Embassy cable, during Patricia Butenis tenure as the US Ambassador here. Butenis had authored that cable at 1.50 pm on Dec. 13, 2009, the day after the now defunct The Sunday Leader exclusive. Butenis had lunch with Fonseka in the company of the then UNP Deputy Leader Karu Jayasuriya, according to the cable. But for the writer the most interesting part had been Butenis declaration that Fonseka’s advisors, namely the late Mangala Samaraweera, Anura Kumara Dissanayake (incumbent President) and Vijitha Herath (current Foreign Minister) wanted him to retract part of the story attributed to him.

Frederica Jansz fiercely stood by her explosive story. She reiterated the accuracy of the story, published on Dec. 13, 2009, during the ‘white flag’ hearing when the writer spoke to her. There is absolutely no reason to suspect Frederica Jansz misinterpreted Fonseka’s response to her queries.

Subsequently, Fonseka repeated the ‘white flag’ allegation at a public rally held in support of his candidature. Many an eyebrow was raised at The Sunday Leader’s almost blind support for Fonseka, against the backdrop of persistent allegations directed at the Army over Lasantha Wickrematunga’s killing. Wickrematunga, an Attorney-at-Law by profession and one-time Private Secretary to Opposition Leader Sirimavo Bandaranaike, was killed on the Attidiya Road, Ratmalana in early January 2009.

The Darusman report, too, dealt withthe ‘white flag’ killings and were central to unsubstantiated Western accusations directed at the Sri Lankan military. Regardless of the political environment in which the ‘white flag’ accusations were made, the issue received global attention for obvious reasons. The accuser had been the war-winning Army Commander who defeated the LTTE at its own game. But, Fonseka insisted, during his meeting with Butenis, as well as the recent public statement that the Rajapaksas had worked behind his back with some members of the international community.

Fresh inquiry needed

Fonseka’s latest declaration that the Rajapaksas wanted to save the LTTE leadership came close on the heels of Deputy British Prime Minister David Lammy’s whistle-stop visit here. The UK, as the leader of the Core Group on Sri Lanka at the Geneva-based United Nations Human Rights Council, spearheads the campaign targeting Sri Lanka.

Lammy was on his way to New Delhi for the AI Impact Summit. The Labour campaigner pushed for action against Sri Lanka during the last UK general election. In fact, taking punitive action against the Sri Lankan military had been a key campaign slogan meant to attract Tamil voters of Sri Lankan origin. His campaign contributed to the declaration of sanctions in March 2025 against Admiral of the Fleet Wasantha Karannagoda, General (retd) Shavendra Silva, General (retd) Jagath Jayasuriya and ex-LTTE commander Karuna, who rebelled against Prabhakaran. Defending Shavendra Silva, Fonseka, about a week after the imposition of the UK sanctions, declared that the British action was unfair.

But Fonseka’s declaration last week had cleared the Rajapaksas of war crimes. Instead, they had been portrayed as traitors. That declaration may undermine the continuous post-war propaganda campaign meant to demonise the Rajapaksas and top ground commanders.

Canada, then a part of the Western clique that blindly towed the US line, declared Sri Lanka perpetrated genocide and also sanctioned ex-Presidents Mahinda Rajapaksa and Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Other countries resorted to action, though such measures weren’t formally announced. General (retd) Jagath Dias and Maj. Gen (retd) Chagie Gallage were two of those targeted.

Against the backdrop of Fonseka’s latest claims, in respect of accountability issues, the urgent need to review action taken against Sri Lanka cannot be delayed. Although the US denied visa when Fonseka was to accompany President Maithripala Sirisena to the UN, in Sept. 2016, he hadn’t been formally accused of war crimes by the western powers, obviously because he served their interests.

On the basis of unsubstantiated allegations that hadn’t been subjected to judicial proceedings, Geneva initiated actions. The US, Canada and UK acted on those accusations. The US sanctioned General Shavendra Silva in Feb. 2020 and Admiral Karannagoda in April 2023.

What compelled Fonseka to change his narrative, 18 years after his Army ended the war? Did Fonseka base his latest version solely on Shanaka de Silva video? Fonseka is on record as claiming that he got that video, via a third party, thereby Shanaka de Silva had nothing to do with his actions.

DNA and formation of DP

Having realised that he couldn’t, under any circumstances, reach a consensus with the UNP to pursue a political career with that party, Fonseka teamed up with the JVP, one of the parties in the coalition that backed his presidential bid in 2010. Fonseka’s current efforts to reach an understanding with the JVP/NPP (President Anura Kumara Dissanayake is the leader of both registered political parties) should be examined against the backdrop of their 2010 alliance.

Under Fonseka’s leadership, the JVP, and a couple of other parties/groups, contested, under the symbol of the Democratic National Alliance (DNA) that had been formed on 22 Nov. 2009. but the grouping pathetically failed to live up to their own expectations. The results of the parliamentary polls, conducted in April 2010, had been devastating and utterly demoralising. Fonseka, who polled about 40% of the national vote at the January 2010 presidential election, ended up with just over 5% of the vote, and the DNA only managed to secure seven seats, including two on the National List. The DNA group consisted of Fonseka, ex-national cricket captain Arjuna Ranatunga, businessman Tiran Alles and four JVPers. Anura Kumara Dissanayake was among the four.

Having been arrested on February 8, 2010, soon after the presidential election, Fonseka was in prison. He was court-martialed for committing “military offences”. He was convicted of corrupt military supply deals and sentenced to three years in prison. Fonseka vacated his seat on 7 Oct .2010. Following a failed legal battle to protect his MP status, Fonseka was replaced by DNA member Jayantha Ketagoda on 8 March 2011. But President Mahinda Rajapaksa released Fonseka in May 2012 following heavy US pressure. The US went to the extent of issuing a warning to the then SLFP General Secretary Maithripala Sirisena that unless President Rajapaksa freed Fonseka he would have to face the consequences (The then Health Minister Sirisena disclosed the US intervention when the writer met him at the Jealth Ministry, as advised by President Rajapaksa)

By then, Fonseka and the JVP had drifted apart and both parties were irrelevant. Somawansa Amarasinghe had been the leader at the time the party decided to join the UNP-led alliance that included the TNA, and the SLMC. The controversial 2010 project had the backing of the US as disclosed by leaked secret diplomatic cables during Patricia Butenis tenure as the US Ambassador here.

In spite of arranging the JVP-led coalition to bring an end to the Rajapaksa rule, Butenis, in a cable dated 15 January 2010, explained the crisis situation here. Butenis said: “There are no examples we know of a regime undertaking wholesale investigations of its own troops or senior officials for war crimes while that regime or government remained in power. In Sri Lanka this is further complicated by the fact that responsibility for many of the alleged crimes rests with the country’s senior civilian and military leadership, including President Rajapaksa and his brothers and opposition candidate General Fonseka.”

Then Fonseka scored a major victory when Election Commissioner Mahinda Deshapriya on 1 April, 2013, recognised his Democratic Party (DNA was registered as DP) with ‘burning flame’ as its symbol. There hadn’t been a previous instance of any service commander registering a political party. While Fonseka received the leadership, ex-Army officer Senaka de Silva, husband of Diana Gamage ((later SJB MP who lost her National List seat over citizenship issue) functioned as the Deputy Leader.

Having covered Fonseka’s political journey, beginning with the day he handed over command to Lt. Gen. Jagath Jayasuriya, in July, 2009, at the old Army Headquarters that was later demolished to pave the way for the Shangri-La hotel complex, the writer covered the hastily arranged media briefing at the Solis reception hall, Pitakotte, on 2 April, 2023. Claiming that his DP was the only alternative to what he called corrupt Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government and bankrupt Ranil Wickremesinghe-led Opposition, a jubilant Fonseka declared himself as the only alternative (‘I am the only alternative,’ with strapline ‘SF alleges Opposition is as bad as govt’. The Island, April 3, 2013).

Fonseka had been overconfident to such an extent, he appealed to members of the government parliamentary group, as well as the Opposition (UNP), to switch allegiance to him. As usual Fonseka was cocky and never realised that 40% of the national vote he received, at the presidential election, belonged to the UNP, TNA and the JVP. Fonseka also disregarded the fact that he no longer had the JVP’s support. He was on his own. The DP never bothered to examine the devastating impact his 2010 relationship with the TNA had on the party. The 2015 general election results devastated Fonseka and underscored that there was absolutely no opportunity for a new party. The result also proved that his role in Sri Lanka’s triumph over the LTTE hadn’t been a decisive factor.

RW comes to SF’s rescue

Fonseka’s DP suffered a humiliating defeat at the August 2015 parliamentary polls. The outcome had been so bad that the DP was left without at least a National List slot. Fonseka was back to square one. If not for UNP leader and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, Fonseka could have been left in the cold. Wickremesinghe accommodated Fonseka on their National List, in place of SLFPer M.K.D.S. Gunawardene, who played a critical role in an influential section of the party and the electorate shifting support to Maithripala Sirisena. Gunawardena passed away on 19 January, 2016. Wickremesinghe and Fonseka signed an agreement at Temple Trees on 3 February, 2016. Fonseka received appointment as National List MP on 9 February, 2016, and served as Minister of Regional Development and, thereafter, as Minister of Wildlife and Sustainable Development, till Oct. 2018. Fonseka lost his Ministry when President Sirisena treacherously sacked Wickremesinghe’s government to pave the way for a new partnership with the Rajapaksas. The Supreme Court discarded that arrangement and brought back the Yahapalana administration but Sirisena, who appointed Fonseka to the lifetime rank of Field Marshal, in recognition of his contribution to the defeat of terrorism, refused to accommodate him in Wickremesinghe’s Cabinet. The President also left out Wasantha Karannagoda and Roshan Goonetilleke. Sirisena appointed them Admiral of the Fleet and Marshal of Air Force, respectively, on 19, Sept. 2019, in the wake of him failing to secure the required backing to contest the Nov. 2019 presidential election.

Wickremesinghe’s UNP repeatedly appealed on behalf of Fonseka in vain to Sirisena. At the 2020 general election, Fonseka switched his allegiance to Sajith Premadasa and contested under the SJB’s ‘telephone’ symbol and was elected from the Gampaha district. Later, following a damaging row with Sajith Premadasa, he quit the SJB as its Chairman and, at the last presidential election, joined the fray as an independent candidate. Having secured just 22,407 votes, Fonseka was placed in distant 9th position. Obviously, Fonseka never received any benefits from support extended to the 2022 Aragalaya and his defeat at the last presidential election seems to have placed him in an extremely difficult position, politically.

Let’s end this piece by reminding that Fonseka gave up the party leadership in early 2024 ahead of the presidential election. Senaka de Silva succeeded Fonseka as DP leader, whereas Dr. Asosha Fernando received appointment as its Chairman. The DP has aligned itself with the NPP. The rest is history.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Midweek Review

Strengths and weaknesses of BRICS+: Implications for Global South

The 16th BRICS Summit, from 22 to 24 October 2024 in Kazan, was attended by 24 heads of state, including the five countries that officially became part of the group on 1 January: Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Egypt and Ethiopia. Argentina finally withdrew from the forum after Javier Milei’s government took office in 2023.

In the end, it changed its strategy and instead of granting full membership made them associated countries adding a large group of 13 countries: two from Latin America (Bolivia and Cuba), three from Africa (Algeria, Nigeria, Uganda) and eight from Asia (Belarus, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Thailand, Turkey, Uzbekistan and Vietnam). This confirms the expansionary intent of the BRICS, initiated last year and driven above all by China, which seeks to turn the group into a relevant multilateral forum, with focus on political than economic interaction, designed to serve its interests in the geopolitical dispute with the United States. This dispute however is not the making of China but has arisen mainly due to the callous bungling of Donald Trump in his second term in office.

China has emerged as the power that could influence the membership within the larger group more than its rival in the region, India. Obviously, the latter is concerned about these developments but seems powerless to stop the trend as more countries realize the need for the development of capacity to resist Western dominance. India in this regard seems to be reluctant possibly due to its defence obligations to the US with Trump declaring war against countries that try to forge partnerships aiming to de-dollarize the global economic system.

The real weakness in BRICS therefore, is the seemingly intractable rivalry between China and India and the impact of this relationship on the other members who are keen to see the organisation grow its capacity to meet its stated goals. China is committed to developing an alternative to the Western dominated world order, particularly the weaponization of the dollar by the US. India does not want to be seen as anti-west and as a result India is often viewed as a reluctant or cautious member of BRICS. This problem seems to be perpetuated due to the ongoing border tensions with China. India therefore has a desire to maintain a level playing field within the group, rather than allowing it to be dominated by Beijing.

Though India seems to be committed to a multipolar world, it prefers focusing on economic cooperation over geopolitical alignment. India thinks the expansion of BRICS initiated by China may dilute its influence within the bloc to the advantage of China. India fears the bloc is shifting toward an anti-Western tilt driven by China and Russia, complicating its own strong ties with the West. India is wary of the new members who are also beneficiaries of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. While China aims to use BRICS for anti-Western geopolitical agendas, India favors focusing on South-South financial cooperation and reforming international institutions. Yet India seems to be not in favour of creating a new currency to replace the dollar which could obviously strengthen the South-South financial transactions bypassing the dollar.

Moreover, India has explicitly opposed the expansion of the bloc to include certain nations, such as Pakistan, indicating a desire to control the group’s agenda, especially during its presidency.

In this equation an important factor is the role that Russia could play. The opinion expressed by the Russian foreign minister in this regard may be significant. Referring to the new admissions the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has said: “The weight, prominence and importance of the candidates and their international standing were the primary factors for us [BRICS members]. It is our shared view that we must recruit like-minded countries into our ranks that believe in a multipolar world order and the need for more democracy and justice in international relations. We need those who champion a bigger role for the Global South in global governance. The six countries whose accession was announced today fully meet these criteria.”

The admission of three major oil producing countries, Saudi Arabia, Iran and UAE is bound to have a significant impact on the future global economic system and consequently may have positive implications for the Global South. These countries would have the ability to decisively help in creating a new international trading system to replace the 5 centuries old system that the West created to transfer wealth from the South to the North. This is so because the petro-dollar is the pillar of the western banking system and is at the very core of the de-dollarizing process that the BRICS is aiming at. This cannot be done without taking on board Saudi Arabia, a staunch ally of the west. BRICS’ expansion, therefore, is its transformation into the most representative community in the world, whose members interact with each other bypassing Western pressure. Saudi Arabia and Iran are actively mending fences, driven by a 2023 China-brokered deal to restore diplomatic ties, reopen embassies, and de-escalate regional tensions. While this detente has brought high-level meetings and a decrease in direct hostility rapprochement is not complete yet and there is hope which also has implications, positive for the South and may not be so for the North.

Though the US may not like what is going on, Europe, which may not endorse all that the former does if one is to go by the speech delivered by the Canadian PM in Brazil recently, may not be displeased about the rapid growth of BRICS. The Guardian UK highlighted expert opinion that BRICS expansion is rather “a symbol of broad support from the global South for the recalibration of the world order.” A top official at the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Caroline Kanter has told the daily, “It is obvious that we [Western countries] are no longer able to set our own conditions and standards. Proposals will be expected from us so that in the future we will be perceived as an attractive partner.” At the same time, the bottom line is that BRICS expansion is perceived in the West as a political victory for Russia and China which augurs well for the future of BRICS and the Global South.

Poor countries, relentlessly battered by the neo-liberal global economy, will greatly benefit if BRICS succeeds in forging a new world order and usher in an era of self-sufficiency and economic independence. There is no hope for them in the present system designed to exploit their natural resources and keep them in a perpetual state of dependency and increasing poverty. BRICS is bound to be further strengthened if more countries from the South join it. Poor countries must come together and with the help of BRICS work towards this goal.

by N. A. de S. Amaratunga

Midweek Review

Eventide Comes to Campus

In the gentle red and gold of the setting sun,

The respected campus in Colombo’s heart,

Is a picture of joyful rest and relief,

Of games taking over from grueling studies,

Of undergrads heading home in joyful ease,

But in those bags they finally unpack at night,

Are big books waiting to be patiently read,

Notes needing completing and re-writing,

And dreamily worked out success plans,

Long awaiting a gutsy first push to take off.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction